Literature Review: Green Consumption Values & Product Responses

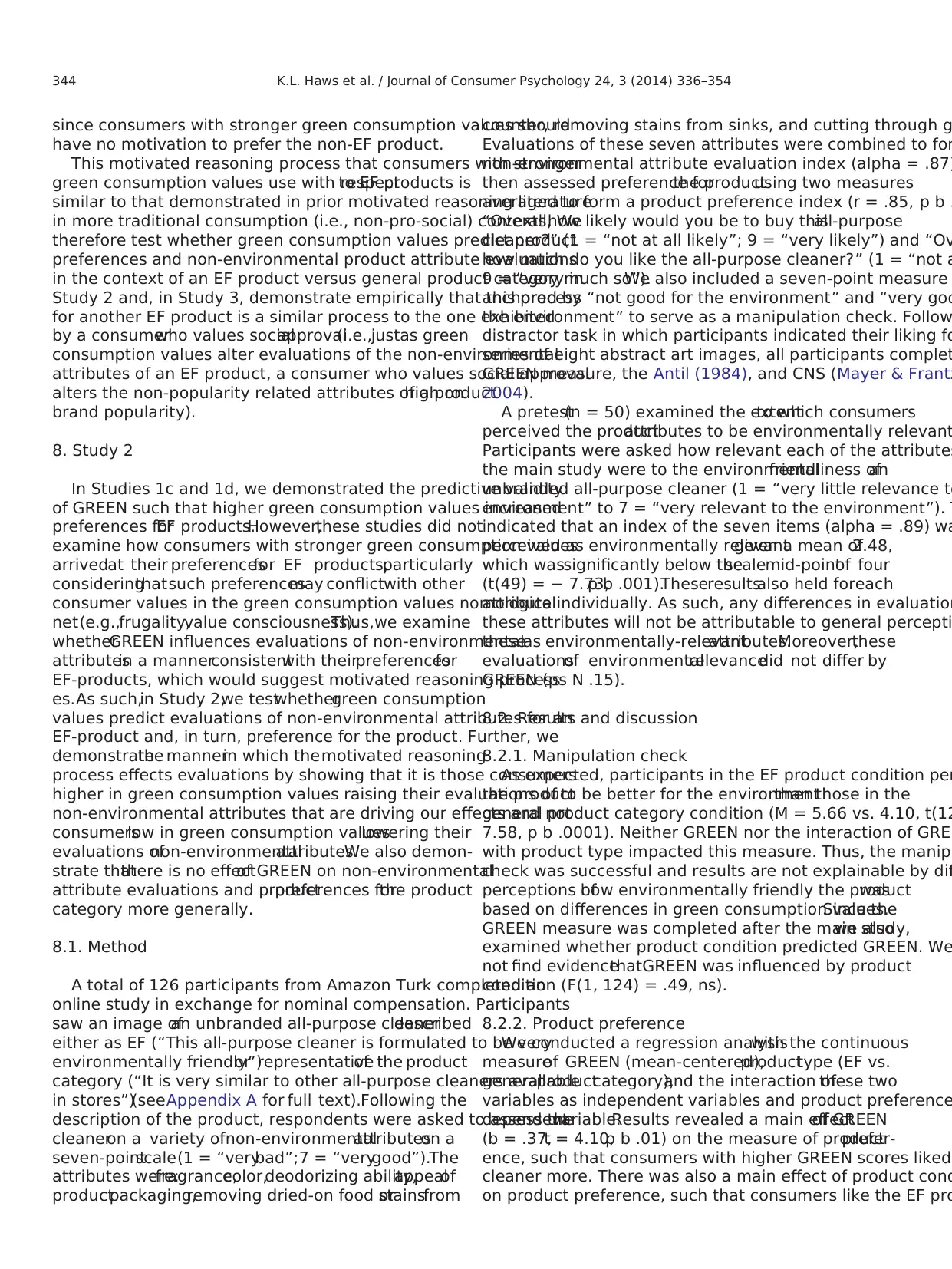

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|19

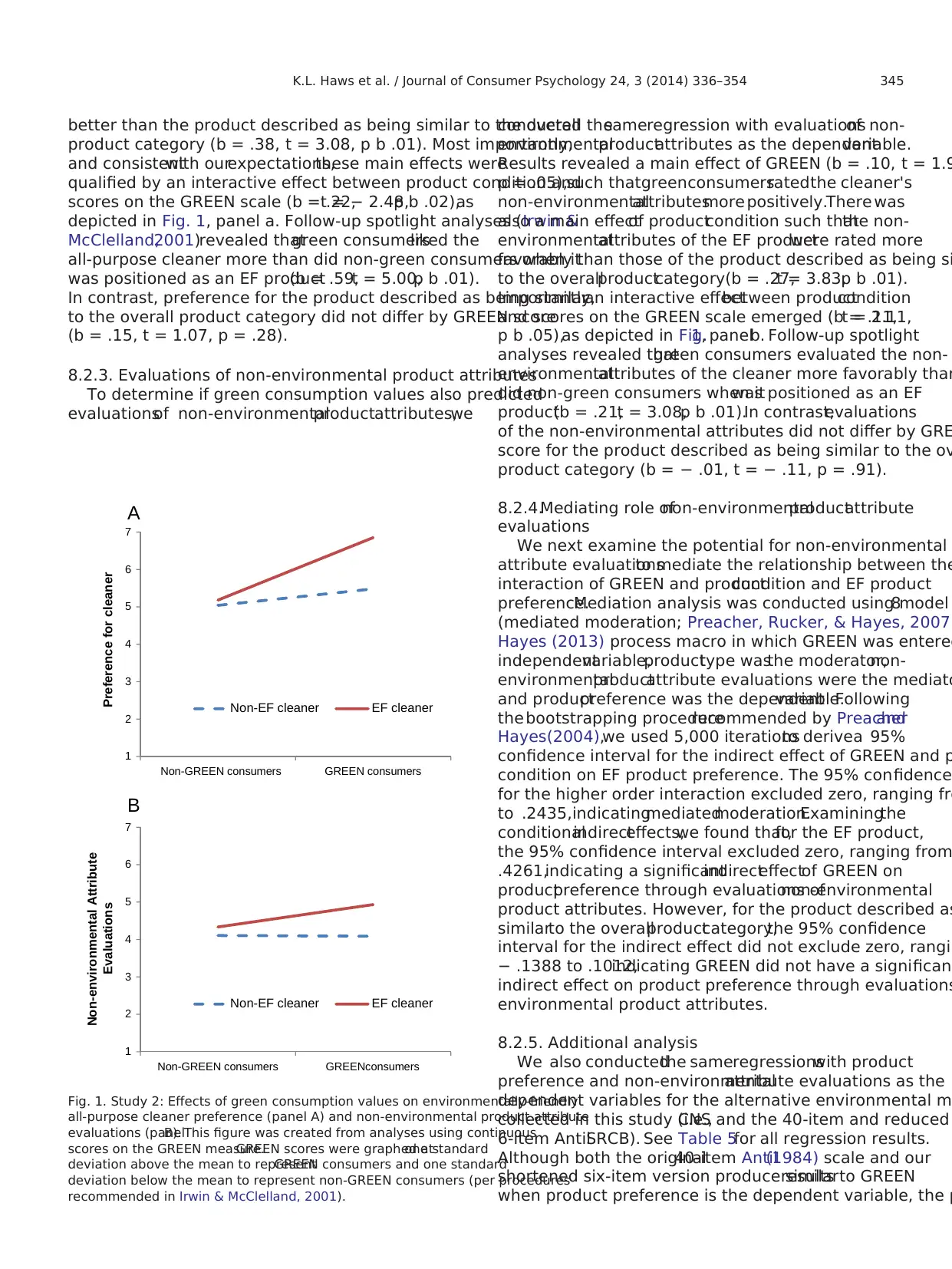

|20147

|490

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review delves into the concept of green consumption values, defined as the tendency to prioritize environmental protection through purchasing and consumption behaviors. It references a study that developed the GREEN scale, a six-item measure designed to reliably capture these values. The review highlights the scale's validation through multiple studies, demonstrating its connection to a broader nomological network encompassing the conservation of financial and physical resources, as well as its predictive power regarding consumer preference for environmentally friendly products. It further investigates how strong green consumption values enhance the appeal of environmentally friendly products by positively influencing the evaluation of their non-environmental attributes. The review also touches upon the increasing attention given to environmentally responsible behavior and the need for concise measures of green consumption values, differentiating it from broader concepts of social responsibility. It concludes by emphasizing the importance of understanding consumer characteristics associated with green consumption values and their role in shaping preferences for sustainable products.

Research Article

Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumptio

and responses to environmentally friendly products☆

Kelly L. Hawsa,⁎, Karen Page Winterichb, Rebecca Walker Naylorc

a Owen Graduate School of Management, 401 21st Ave South, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203, USA

b Smeal College of Business, Pennsylvania State University, 449 Business Building, University Park, PA, 16802, USA

c Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 2100 Neil Avenue, 538 Fisher Hall, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Received 30 October 2012; received in revised form 23 October 2013; accepted 4 November 2013

Available online 13 November 2013

Abstract

The primary goal of this research is to conceptualize and develop a scale of green consumption values,which we define as the tendency to

express the value of environmental protection through one's purchases and consumption behaviors. Across six studies, we d

item measure we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to capture green consumption values in a reliable, valid, and p

We furthertheorize and empirically demonstrate thatgreen consumption values are partof a largernomologicalnetwork associated with

conservation of not just environmental resources but also personal financial and physical resources. Finally, we demonstrate

predicts consumer preference for environmentally friendly products. In doing so, we demonstrate that stronger green consu

preference for environmentally friendly products through more favorable evaluations of the non-environmental attributes of

results have important implications for consumer responses to the growing number of environmentally friendly products.

© 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Sustainability; Scale development; Environmental marketing; Green marketing; Motivated reasoning

1. Introduction

In today's marketplace,consumers are increasingly faced

with choicesbetween“green”productsand their more

traditionalcounterparts,as more firms produceproducts

whose compositionand/or packagingare positionedas

environmentally friendly. For example, Wal-Mart is pressuring

its suppliers like GeneralElectric and Procter& Gamble to

provideenvironmentally friendly products(Rosenbloom &

Barbaro,2009).Moreover,many corporateinitiativesnow

focus exclusively on environmentalissues,such as KPMG's

GlobalGreen Initiative (KPMG,2010;see also Menon &

Menon, 1997). However, the extent to which consumers va

and therefore positively respond to such offerings through

value-consistent behavior remains questionable.

Clearly not all consumers are willing to buy environment

friendly (EF) products.1 Some consumers may be reluctantto

purchase EF products because they are perceived to be les

effective (Luchset al., 2010).Cost may also be a critical

☆ The authors gratefully acknowledge that this project was funded by the Alton M.

& Marion R. Withers Retailing Research Grant Center for Retailing Studies, Texas

A&M University. The first two authors contributed equally to this research.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: Kelly.haws@vanderbilt.edu (K.L. Haws),

kpw2@psu.edu (K.P. Winterich), naylor_53@fisher.osu.edu (R.W. Naylor).

1 We define an environmentally friendly product as one with at least one

environmental attribute. An “environmental attribute” is an attribute that

impact of the product on the environment. As such, environmental produc

can be positive (i.e., the product has little to no negative impact on the en

and is considered environmentally friendly) or negative (i.e., the product h

environment). This definition is consistent with the definition of “ethical at

used in past research (Irwin & Naylor, 2009; Luchs, Naylor, Irwin, & Raghu

2010;Peloza,White,& Shang,2013),with thekey distinction being that

environmental attributes are specifically about the environment, not more

about any issue that a consumer sees as relevant to their values/ethics (e

labor concerns;unsafe work environments,donations to charity,discrimination;

Mohr & Webb, 2005).

1057-7408/$ -see front matter © 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336 – 354

Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumptio

and responses to environmentally friendly products☆

Kelly L. Hawsa,⁎, Karen Page Winterichb, Rebecca Walker Naylorc

a Owen Graduate School of Management, 401 21st Ave South, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203, USA

b Smeal College of Business, Pennsylvania State University, 449 Business Building, University Park, PA, 16802, USA

c Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 2100 Neil Avenue, 538 Fisher Hall, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Received 30 October 2012; received in revised form 23 October 2013; accepted 4 November 2013

Available online 13 November 2013

Abstract

The primary goal of this research is to conceptualize and develop a scale of green consumption values,which we define as the tendency to

express the value of environmental protection through one's purchases and consumption behaviors. Across six studies, we d

item measure we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to capture green consumption values in a reliable, valid, and p

We furthertheorize and empirically demonstrate thatgreen consumption values are partof a largernomologicalnetwork associated with

conservation of not just environmental resources but also personal financial and physical resources. Finally, we demonstrate

predicts consumer preference for environmentally friendly products. In doing so, we demonstrate that stronger green consu

preference for environmentally friendly products through more favorable evaluations of the non-environmental attributes of

results have important implications for consumer responses to the growing number of environmentally friendly products.

© 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Sustainability; Scale development; Environmental marketing; Green marketing; Motivated reasoning

1. Introduction

In today's marketplace,consumers are increasingly faced

with choicesbetween“green”productsand their more

traditionalcounterparts,as more firms produceproducts

whose compositionand/or packagingare positionedas

environmentally friendly. For example, Wal-Mart is pressuring

its suppliers like GeneralElectric and Procter& Gamble to

provideenvironmentally friendly products(Rosenbloom &

Barbaro,2009).Moreover,many corporateinitiativesnow

focus exclusively on environmentalissues,such as KPMG's

GlobalGreen Initiative (KPMG,2010;see also Menon &

Menon, 1997). However, the extent to which consumers va

and therefore positively respond to such offerings through

value-consistent behavior remains questionable.

Clearly not all consumers are willing to buy environment

friendly (EF) products.1 Some consumers may be reluctantto

purchase EF products because they are perceived to be les

effective (Luchset al., 2010).Cost may also be a critical

☆ The authors gratefully acknowledge that this project was funded by the Alton M.

& Marion R. Withers Retailing Research Grant Center for Retailing Studies, Texas

A&M University. The first two authors contributed equally to this research.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: Kelly.haws@vanderbilt.edu (K.L. Haws),

kpw2@psu.edu (K.P. Winterich), naylor_53@fisher.osu.edu (R.W. Naylor).

1 We define an environmentally friendly product as one with at least one

environmental attribute. An “environmental attribute” is an attribute that

impact of the product on the environment. As such, environmental produc

can be positive (i.e., the product has little to no negative impact on the en

and is considered environmentally friendly) or negative (i.e., the product h

environment). This definition is consistent with the definition of “ethical at

used in past research (Irwin & Naylor, 2009; Luchs, Naylor, Irwin, & Raghu

2010;Peloza,White,& Shang,2013),with thekey distinction being that

environmental attributes are specifically about the environment, not more

about any issue that a consumer sees as relevant to their values/ethics (e

labor concerns;unsafe work environments,donations to charity,discrimination;

Mohr & Webb, 2005).

1057-7408/$ -see front matter © 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336 – 354

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

deterrent; eco-friendly products have historically cost more than

their traditional2 counterparts (Dale, 2008; Mintel, 2009), and not

all consumers are willing to pay price premiums for ethical or EF

products (Mintel, 2010). Clearly, some consumers are willing to

purchase EF products while others are not, which suggests that

there are individualdifferences among consumers in the value

they placeon conserving theenvironmentin consumption

settings.Therefore,the primary objective of our research is to

develop a method to understand differences across consumers

who do and do not value conserving the environment as part of

their consumption behavior. As such, we introduce the construct

of green consumption values,which we formally define as the

tendencyto expressthe valueof environmentalprotection

through one's purchases and consumption behaviors.

Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-item measure

we develop (i.e.,the GREEN scale)can be used to reliably

capture green consumption values.We furthersuggestthat

green consumption valuesare partof a largernomological

network associated with conservation of not just environmental

resources but also personal financial and physical resources. In

otherswords,consumerswith strongergreen consumption

values (i.e.,“green” consumers) are generally oriented toward

protecting resources atboth the environmentaland personal

level.We testthese proposed nomologicalnetwork relation-

ships empirically as part of our larger scale development effort.

Finally,to further validate the scale,we demonstrate thatthe

GREEN scale predicts consumer preference for EF products. In

doing so,we show thatstrongergreen consumption values

increase preference forEF products through more favorable

evaluationsof these products'non-environmentalattributes,

consistent with consumers' use of motivated reasoning in other

decision making contexts (Kunda, 1990).

2. Understanding green consumers

Environmentally responsible behavior is receiving increasing

attention in theliterature (Catlin & Wang,2013;Leonidou,

Katsikeas, & Morgan, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; Trudel & Argo,

2013; White & Simpson,2013).This focus is consistent with a

broader interest in understanding socially responsible consumption

that has persistedfor severaldecades(e.g.,Anderson&

Cunningham, 1972; Antil, 1984; Roberts, 1995; Webb, Mohr, &

Harris,2008;Webster,1975).However,the extentto which

consumers' environmentally responsible behaviors differ among

individuals, and why, is not clear given that existing research has

focused on responses to environmental products at the firm level

(Leonidou et al., 2013) or as a result of differing situational factors

(Catlin & Wang,2013;Peloza etal.,2013;White & Simpson,

2013). To be sure, past research aimed at understanding socially

responsible consumption has soughtto understand differences

among individual consumers. Yet, this research focused on broader

socialissues,as illustrated by Roberts' (1993) description of a

socially responsible consumer as “one who purchases products and

services perceived to have a positive (or less negative) in

the environment or who patronizes businesses that attem

related positive social change” (p. 140).

Although we acknowledge thatenvironmentalissues have

often been conceptualized as part of a broader effort to u

socially conscious consumers (Mohr,Webb,& Harris,2001;

Roberts,1993;Webster,1975),the more generalnotion of

socially responsibleconsumptionis multifaceted.As such,

investigations of socially conscious consumption have oft

to long and complex measures designed to capture the fu

of the constructs involved,which include issues notdirectly

related to the environment (see, for example, Antil, 1984

et al., 2008). Other scales designed to measure consume

responsibility have become dated asperceptionsof socially

responsible behaviors change overtime (Dunlap,Van Liere,

Mertig, & Jones, 2000).3 Thus, our primary goal is to develop a

concise measure ofexclusively green consumption values,as

opposed to broader attitudes toward socially responsible

or environmental consciousness. As we develop this mea

also seek to identify the consumer characteristics associa

green consumption valuesas partof a broadernomological

network and understanding of the green consumer. In ad

the desire of consumers with strong green consumption v

use society's environmentalresources wisely (i.e.,clean water,

cleanair, flora, and fauna;Cunningham,Cunningham,&

Woodworth, 2001), we suggest that green consumers als

conservation of their personal resources.

As such,we focus ourconceptualization and nomological

networkof greenconsumptionvalueson the underlying

characteristics of concern for both individual-level financ

physicalresources.Specifically,we expectconsumerswith

stronger green consumption values to be more conscient

the use of their financial resources, consistent with past r

suggesting thatgreen consumption (orconservation)may be

related to concerns about spending money. For example,

study,price consciousness was the only variable,otherthan

household characteristics (i.e., number of rooms) and fam

to significantly predict energy use (Heslop, Moran, & Cou

1981). In another study, care in shopping (reflecting shop

specials and checking prices) significantly predicted mak

special effort to buy environmentally-friendly products fo

men and women (Shrum, McCarty, & Lowrey, 1995).

Relatedly,we also expectconsumers with strongergreen

consumption valuesto be morecarefulusersof physical

resources, for example by using their products fully and b

using more than the necessary amountof a productfor it to

perform its function effectively,as suggested by Lastovicka,

Bettencourt,Hughner,and Kuntze's(1999)work on frugal

consumption.Specifically,we suggestthatgreen consumers

will be reluctant to give up their physical possessions bec

they willseek to extractfull and complete value from goods

2 When we refer to a “traditional” product, we refer to offerings in which there

is no known environmentally friendly attribute, though they are not necessarily

harmful to the environment.

3 For example, some scale items use figures that become dated (e.g.,

be willing to accept an increase in my family's total expenses of $120 n

to promote the wise use of natural resources” from Antil,1984),while others

focus on avoiding trade with certain countries due to policies that have

over time (e.g., “I do not buy products from companies that have invest

South Africa” from Roberts, 1995).

337K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

their traditional2 counterparts (Dale, 2008; Mintel, 2009), and not

all consumers are willing to pay price premiums for ethical or EF

products (Mintel, 2010). Clearly, some consumers are willing to

purchase EF products while others are not, which suggests that

there are individualdifferences among consumers in the value

they placeon conserving theenvironmentin consumption

settings.Therefore,the primary objective of our research is to

develop a method to understand differences across consumers

who do and do not value conserving the environment as part of

their consumption behavior. As such, we introduce the construct

of green consumption values,which we formally define as the

tendencyto expressthe valueof environmentalprotection

through one's purchases and consumption behaviors.

Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-item measure

we develop (i.e.,the GREEN scale)can be used to reliably

capture green consumption values.We furthersuggestthat

green consumption valuesare partof a largernomological

network associated with conservation of not just environmental

resources but also personal financial and physical resources. In

otherswords,consumerswith strongergreen consumption

values (i.e.,“green” consumers) are generally oriented toward

protecting resources atboth the environmentaland personal

level.We testthese proposed nomologicalnetwork relation-

ships empirically as part of our larger scale development effort.

Finally,to further validate the scale,we demonstrate thatthe

GREEN scale predicts consumer preference for EF products. In

doing so,we show thatstrongergreen consumption values

increase preference forEF products through more favorable

evaluationsof these products'non-environmentalattributes,

consistent with consumers' use of motivated reasoning in other

decision making contexts (Kunda, 1990).

2. Understanding green consumers

Environmentally responsible behavior is receiving increasing

attention in theliterature (Catlin & Wang,2013;Leonidou,

Katsikeas, & Morgan, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; Trudel & Argo,

2013; White & Simpson,2013).This focus is consistent with a

broader interest in understanding socially responsible consumption

that has persistedfor severaldecades(e.g.,Anderson&

Cunningham, 1972; Antil, 1984; Roberts, 1995; Webb, Mohr, &

Harris,2008;Webster,1975).However,the extentto which

consumers' environmentally responsible behaviors differ among

individuals, and why, is not clear given that existing research has

focused on responses to environmental products at the firm level

(Leonidou et al., 2013) or as a result of differing situational factors

(Catlin & Wang,2013;Peloza etal.,2013;White & Simpson,

2013). To be sure, past research aimed at understanding socially

responsible consumption has soughtto understand differences

among individual consumers. Yet, this research focused on broader

socialissues,as illustrated by Roberts' (1993) description of a

socially responsible consumer as “one who purchases products and

services perceived to have a positive (or less negative) in

the environment or who patronizes businesses that attem

related positive social change” (p. 140).

Although we acknowledge thatenvironmentalissues have

often been conceptualized as part of a broader effort to u

socially conscious consumers (Mohr,Webb,& Harris,2001;

Roberts,1993;Webster,1975),the more generalnotion of

socially responsibleconsumptionis multifaceted.As such,

investigations of socially conscious consumption have oft

to long and complex measures designed to capture the fu

of the constructs involved,which include issues notdirectly

related to the environment (see, for example, Antil, 1984

et al., 2008). Other scales designed to measure consume

responsibility have become dated asperceptionsof socially

responsible behaviors change overtime (Dunlap,Van Liere,

Mertig, & Jones, 2000).3 Thus, our primary goal is to develop a

concise measure ofexclusively green consumption values,as

opposed to broader attitudes toward socially responsible

or environmental consciousness. As we develop this mea

also seek to identify the consumer characteristics associa

green consumption valuesas partof a broadernomological

network and understanding of the green consumer. In ad

the desire of consumers with strong green consumption v

use society's environmentalresources wisely (i.e.,clean water,

cleanair, flora, and fauna;Cunningham,Cunningham,&

Woodworth, 2001), we suggest that green consumers als

conservation of their personal resources.

As such,we focus ourconceptualization and nomological

networkof greenconsumptionvalueson the underlying

characteristics of concern for both individual-level financ

physicalresources.Specifically,we expectconsumerswith

stronger green consumption values to be more conscient

the use of their financial resources, consistent with past r

suggesting thatgreen consumption (orconservation)may be

related to concerns about spending money. For example,

study,price consciousness was the only variable,otherthan

household characteristics (i.e., number of rooms) and fam

to significantly predict energy use (Heslop, Moran, & Cou

1981). In another study, care in shopping (reflecting shop

specials and checking prices) significantly predicted mak

special effort to buy environmentally-friendly products fo

men and women (Shrum, McCarty, & Lowrey, 1995).

Relatedly,we also expectconsumers with strongergreen

consumption valuesto be morecarefulusersof physical

resources, for example by using their products fully and b

using more than the necessary amountof a productfor it to

perform its function effectively,as suggested by Lastovicka,

Bettencourt,Hughner,and Kuntze's(1999)work on frugal

consumption.Specifically,we suggestthatgreen consumers

will be reluctant to give up their physical possessions bec

they willseek to extractfull and complete value from goods

2 When we refer to a “traditional” product, we refer to offerings in which there

is no known environmentally friendly attribute, though they are not necessarily

harmful to the environment.

3 For example, some scale items use figures that become dated (e.g.,

be willing to accept an increase in my family's total expenses of $120 n

to promote the wise use of natural resources” from Antil,1984),while others

focus on avoiding trade with certain countries due to policies that have

over time (e.g., “I do not buy products from companies that have invest

South Africa” from Roberts, 1995).

337K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

before discarding them, consistent with Haws, Naylor, Coulter,

and Bearden's(2012)work on productretention tendency.

Additionally,we theorize thatgreen consumers willbe more

likely to be innovative users of existing physical resources, that

is, that they will creatively reuse and find multiple uses for their

products,as suggested by Price and Ridgeway's (1983) work

on use innovativeness, a behavior indicative of self-recycling.

To understand consumers'green consumption values,the

corresponding nomological net, and their predictive validity, we

firstconducta series of four scale developmentand validation

studies. In Study 1a, we discuss our development of a six-item

scale to measure green consumption values,compare itto an

existing measureof socially responsibleconsumption,and

establish a nomologicalnetwork including concern forboth

personalfinancialand physicalresources.Study 1b provides

further validation of the scale and nomological network using an

adult sample. Study 1c demonstrates the test–retest reliability of

the scale while also providing evidence ofpredictive validity

relative to existing measures of environmentalattitudes drawn

from the literature.Study 1d provides furthersupportfor the

predictive validity of our green measure with actual choice.

3. Study 1a: Developing the GREEN scale and testing the

nomological network

3.1. Participants and method

To develop the GREEN scale, we initially compiled a list of

58 items intended to measure how much consumers valued the

environment when making consumption decisions. These items

were generated by the authors by adapting items from existing

environmental attitude scales and drawing upon popular press

articlesregarding green marketing (e.g.,Dale,2008;Stone,

2009).We presented this setof items,plus othermeasures

described below,to 264 undergraduate studentswho were

participating in a multi-phased study for course credit.Given

our intention to parsimoniously assess the tendency to express

the importanceof environmentalprotection through one's

purchasesand consumptionbehaviors,we anticipateda

one-factor model for our GREEN scale.

In addition to the58 proposed itemsto assessgreen

consumption values,we also included the 40-item measure of

Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior(SRCB) devel-

oped by Antilin 1984.Our intentwas notto compare our

measure againstevery existing measure ofenvironmentalor

socially responsible values, attitudes, and behaviors, but rather

to develop aconcisescalethatwould noteasily become

outdated and would compare well with past measures. We used

the Antil (1984) scale for these benchmarking purposes because

of its inclusion of environmental values as a key part of socially

responsible consumption aswell as its existing use in the

literature.We anticipated thatour six-item measure would be

strongly related to this existing 40-item measure.

Additionally,we sought to examine our proposed nomolog-

ical network with respectto the relationship between green

consumption values and existing measures of consumers' use of

personalfinancialand physicalresources.The firstof these

measureswas Lastovickaet al.'s (1999)frugalityscale.

Lastovicka etal. (1999) characterized frugality as being about

both the careful acquisition and careful consumption of goo

encompassing the vigilantuse ofboth financialand physical

resources. Therefore, we expect GREEN to be related to fru

because of the emphasis a frugal consumer places on the c

use of financialresources in acquiring goods and concern for

physicalpossessionsduring consumption (Lastovicka etal.,

1999).We also measuredconsumerspendingself-control

(CSSC) because we expect greener consumers to exercise

thoughtfulness and controlin their spending decision making,

which would be implied in a positive relationship between

GREEN and CSSC (Haws,Bearden,& Nenkov,2012).We

also included Lichtenstein,Netemeyer,and Burton's(1990)

measure of price consciousness and Lichtenstein, Ridgway

Netemeyer's (1993) measure of value consciousness. We e

GREEN to be positively related to both of these constructs a

these tendencies also suggest careful use of financial resou

To address the conservative use of personal physical res

beyond that captured in Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality

we measured the tendency to retain or relinquish possessio

(using the product retention tendency scale; Haws, Naylor

2012) and innovativeness in the use and reuse of products

Price & Ridgeway's, 1983 three-dimensional use innovative

scale).We expectthese constructs to be positively related to

GREEN, as they involve a focus on the careful disposition a

use of physical resources.

Finally,to assess the potential for consumers to misrepres

themselves by responding in a socially desirable manner,which

may be of particularconcernfor sociallyresponsibleand

environmentally friendly behaviors(Luchset al., 2010),we

assessedthe relationshipbetweenGREEN and both self-

deceptiveenhancementand impression managementusing a

shortened version ofPaulhus(1998)Balanced Inventory of

Desirable Responding (BIDR) scale.

3.2. Results

We first conducted a series of factor analyses to reduce t

set of 58 items.An initial exploratory factor analysis revealed

that there was one primary factor that emerged from the s

58 items, with an eigenvalue of 19.23 for the first factor ve

5.00 for the second factor, which explained 33% versus 9%

variance,respectively.A careful inspectionof the factor

loadings forthe second and subsequentfactors showed that

the loadings were significantly smaller than the loadings on

first factor,supportingthe proposedone-factormodelas

sufficiently capturing our construct.4 As such,we focused on

identifying items from this one factor that would assess gre

consumption values.

We found that 10 items had a loading of at least .70 or h

the first factor. We carefully examined these 10 items to lim

use of redundant or unclear items in order to use as few ite

4 We also compared theone-factormodelto a seriesof othermodels

including two,three,and fourfactormodels,and we consistently found

evidence that one factor provided the best fitting model.

338 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

and Bearden's(2012)work on productretention tendency.

Additionally,we theorize thatgreen consumers willbe more

likely to be innovative users of existing physical resources, that

is, that they will creatively reuse and find multiple uses for their

products,as suggested by Price and Ridgeway's (1983) work

on use innovativeness, a behavior indicative of self-recycling.

To understand consumers'green consumption values,the

corresponding nomological net, and their predictive validity, we

firstconducta series of four scale developmentand validation

studies. In Study 1a, we discuss our development of a six-item

scale to measure green consumption values,compare itto an

existing measureof socially responsibleconsumption,and

establish a nomologicalnetwork including concern forboth

personalfinancialand physicalresources.Study 1b provides

further validation of the scale and nomological network using an

adult sample. Study 1c demonstrates the test–retest reliability of

the scale while also providing evidence ofpredictive validity

relative to existing measures of environmentalattitudes drawn

from the literature.Study 1d provides furthersupportfor the

predictive validity of our green measure with actual choice.

3. Study 1a: Developing the GREEN scale and testing the

nomological network

3.1. Participants and method

To develop the GREEN scale, we initially compiled a list of

58 items intended to measure how much consumers valued the

environment when making consumption decisions. These items

were generated by the authors by adapting items from existing

environmental attitude scales and drawing upon popular press

articlesregarding green marketing (e.g.,Dale,2008;Stone,

2009).We presented this setof items,plus othermeasures

described below,to 264 undergraduate studentswho were

participating in a multi-phased study for course credit.Given

our intention to parsimoniously assess the tendency to express

the importanceof environmentalprotection through one's

purchasesand consumptionbehaviors,we anticipateda

one-factor model for our GREEN scale.

In addition to the58 proposed itemsto assessgreen

consumption values,we also included the 40-item measure of

Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior(SRCB) devel-

oped by Antilin 1984.Our intentwas notto compare our

measure againstevery existing measure ofenvironmentalor

socially responsible values, attitudes, and behaviors, but rather

to develop aconcisescalethatwould noteasily become

outdated and would compare well with past measures. We used

the Antil (1984) scale for these benchmarking purposes because

of its inclusion of environmental values as a key part of socially

responsible consumption aswell as its existing use in the

literature.We anticipated thatour six-item measure would be

strongly related to this existing 40-item measure.

Additionally,we sought to examine our proposed nomolog-

ical network with respectto the relationship between green

consumption values and existing measures of consumers' use of

personalfinancialand physicalresources.The firstof these

measureswas Lastovickaet al.'s (1999)frugalityscale.

Lastovicka etal. (1999) characterized frugality as being about

both the careful acquisition and careful consumption of goo

encompassing the vigilantuse ofboth financialand physical

resources. Therefore, we expect GREEN to be related to fru

because of the emphasis a frugal consumer places on the c

use of financialresources in acquiring goods and concern for

physicalpossessionsduring consumption (Lastovicka etal.,

1999).We also measuredconsumerspendingself-control

(CSSC) because we expect greener consumers to exercise

thoughtfulness and controlin their spending decision making,

which would be implied in a positive relationship between

GREEN and CSSC (Haws,Bearden,& Nenkov,2012).We

also included Lichtenstein,Netemeyer,and Burton's(1990)

measure of price consciousness and Lichtenstein, Ridgway

Netemeyer's (1993) measure of value consciousness. We e

GREEN to be positively related to both of these constructs a

these tendencies also suggest careful use of financial resou

To address the conservative use of personal physical res

beyond that captured in Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality

we measured the tendency to retain or relinquish possessio

(using the product retention tendency scale; Haws, Naylor

2012) and innovativeness in the use and reuse of products

Price & Ridgeway's, 1983 three-dimensional use innovative

scale).We expectthese constructs to be positively related to

GREEN, as they involve a focus on the careful disposition a

use of physical resources.

Finally,to assess the potential for consumers to misrepres

themselves by responding in a socially desirable manner,which

may be of particularconcernfor sociallyresponsibleand

environmentally friendly behaviors(Luchset al., 2010),we

assessedthe relationshipbetweenGREEN and both self-

deceptiveenhancementand impression managementusing a

shortened version ofPaulhus(1998)Balanced Inventory of

Desirable Responding (BIDR) scale.

3.2. Results

We first conducted a series of factor analyses to reduce t

set of 58 items.An initial exploratory factor analysis revealed

that there was one primary factor that emerged from the s

58 items, with an eigenvalue of 19.23 for the first factor ve

5.00 for the second factor, which explained 33% versus 9%

variance,respectively.A careful inspectionof the factor

loadings forthe second and subsequentfactors showed that

the loadings were significantly smaller than the loadings on

first factor,supportingthe proposedone-factormodelas

sufficiently capturing our construct.4 As such,we focused on

identifying items from this one factor that would assess gre

consumption values.

We found that 10 items had a loading of at least .70 or h

the first factor. We carefully examined these 10 items to lim

use of redundant or unclear items in order to use as few ite

4 We also compared theone-factormodelto a seriesof othermodels

including two,three,and fourfactormodels,and we consistently found

evidence that one factor provided the best fitting model.

338 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

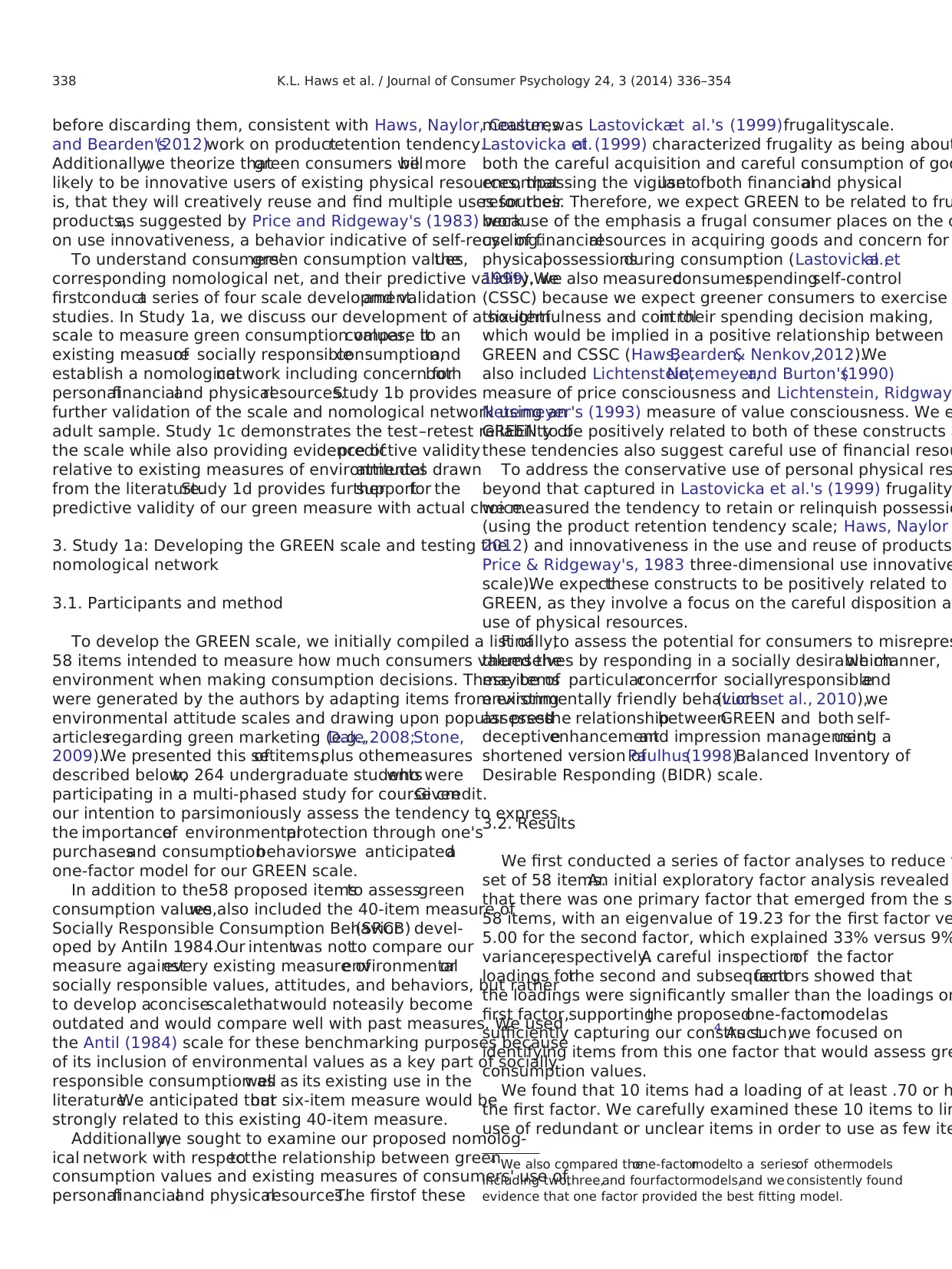

possible while retaining high validity,which is consistentwith

recommendations by Bearden, Netemeyer, and Haws (2010) and

Bearden,Netemeyer,and Teel(1989).This process led to the

elimination of four items.Accordingly,we determined thatthe

remaining six items were highly reliable (α = .89)and could

succinctly capture the green construct (See Table 1 for final items).

Confirmatory factoranalysis using the six items demonstrated

strong fit of the model (see Table 1). Procedures recommended by

Fornelland Larcker(1981)showed:(1) the average variance

extracted (.61) exceeded the recommended value of .50 and (2)

constructreliability (.90)also implied a good fitting model.

From both a managerialand a research perspective,the most

parsimoniousmeasurepossiblethat still capturesthe core

constructfully is the mostuseful(Haws,Nayloret al.,2012;

Richins, 2004).

With this six-item scale,we proceeded to analyzethe

relationships with Antil's SRCB and other constructs theo

as part of the nomological network. All existing measures

assessed for reliability and averaged into indices followin

instructions of the original scales, except for price consci

which was reverse-coded, such that higher values indicat

price consciousness, to be consistent with the other mea

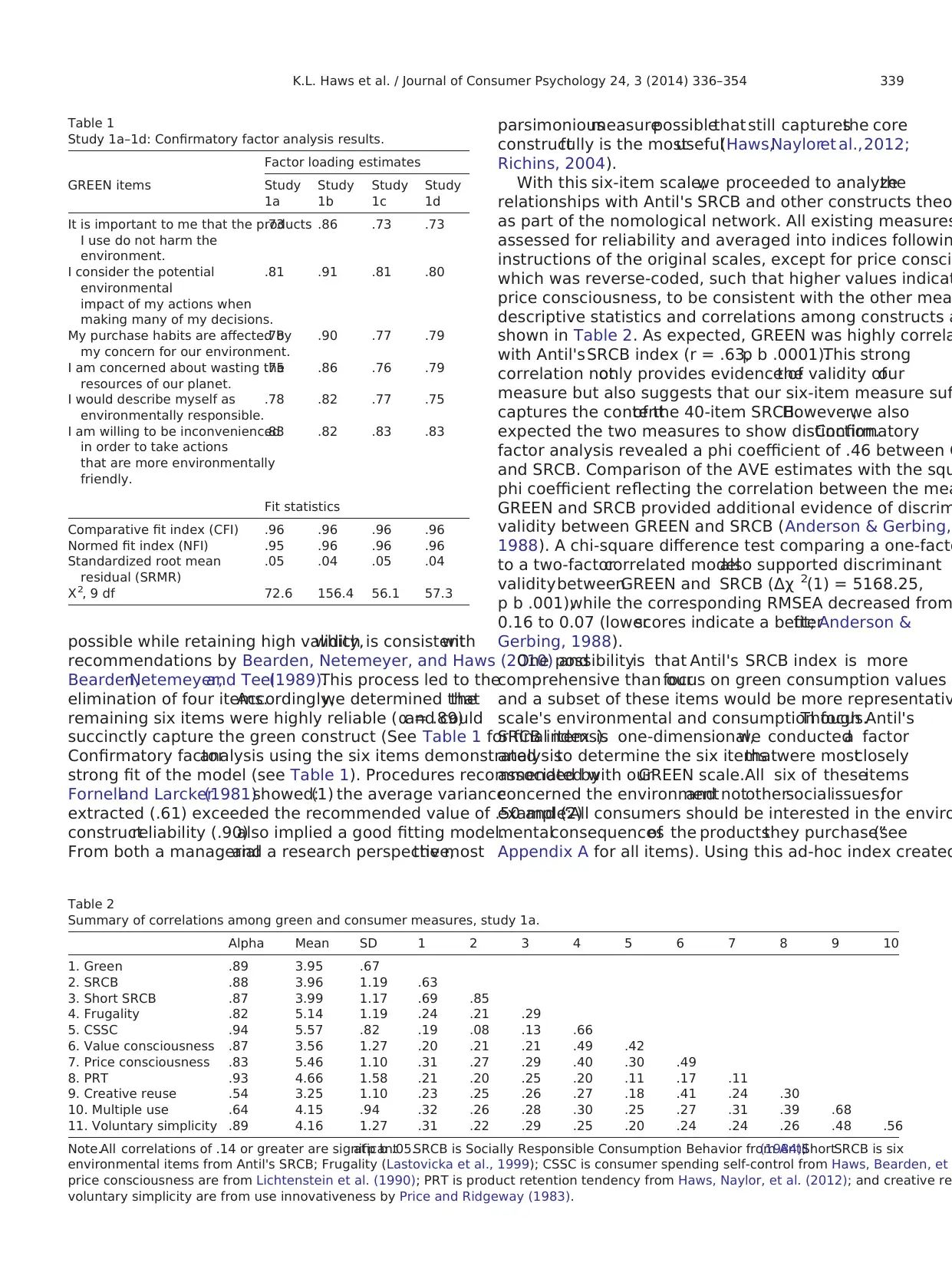

descriptive statistics and correlations among constructs a

shown in Table 2. As expected, GREEN was highly correla

with Antil'sSRCB index (r = .63,p b .0001).This strong

correlation notonly provides evidence ofthe validity ofour

measure but also suggests that our six-item measure suffi

captures the contentof the 40-item SRCB.However,we also

expected the two measures to show distinction.Confirmatory

factor analysis revealed a phi coefficient of .46 between G

and SRCB. Comparison of the AVE estimates with the squ

phi coefficient reflecting the correlation between the mea

GREEN and SRCB provided additional evidence of discrim

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988). A chi-square difference test comparing a one-facto

to a two-factorcorrelated modelalso supported discriminant

validitybetweenGREEN and SRCB (Δχ 2(1) = 5168.25,

p b .001),while the corresponding RMSEA decreased from

0.16 to 0.07 (lowerscores indicate a betterfit; Anderson &

Gerbing, 1988).

One possibilityis that Antil's SRCB index is more

comprehensive than ourfocus on green consumption values

and a subset of these items would be more representativ

scale's environmental and consumption focus.Though Antil's

SRCB index is one-dimensional,we conducteda factor

analysisto determine the six itemsthatwere mostclosely

associated with ourGREEN scale.All six of theseitems

concerned the environmentand notothersocialissues;for

example:“All consumers should be interested in the enviro

mentalconsequencesof the productsthey purchase”(see

Appendix A for all items). Using this ad-hoc index created

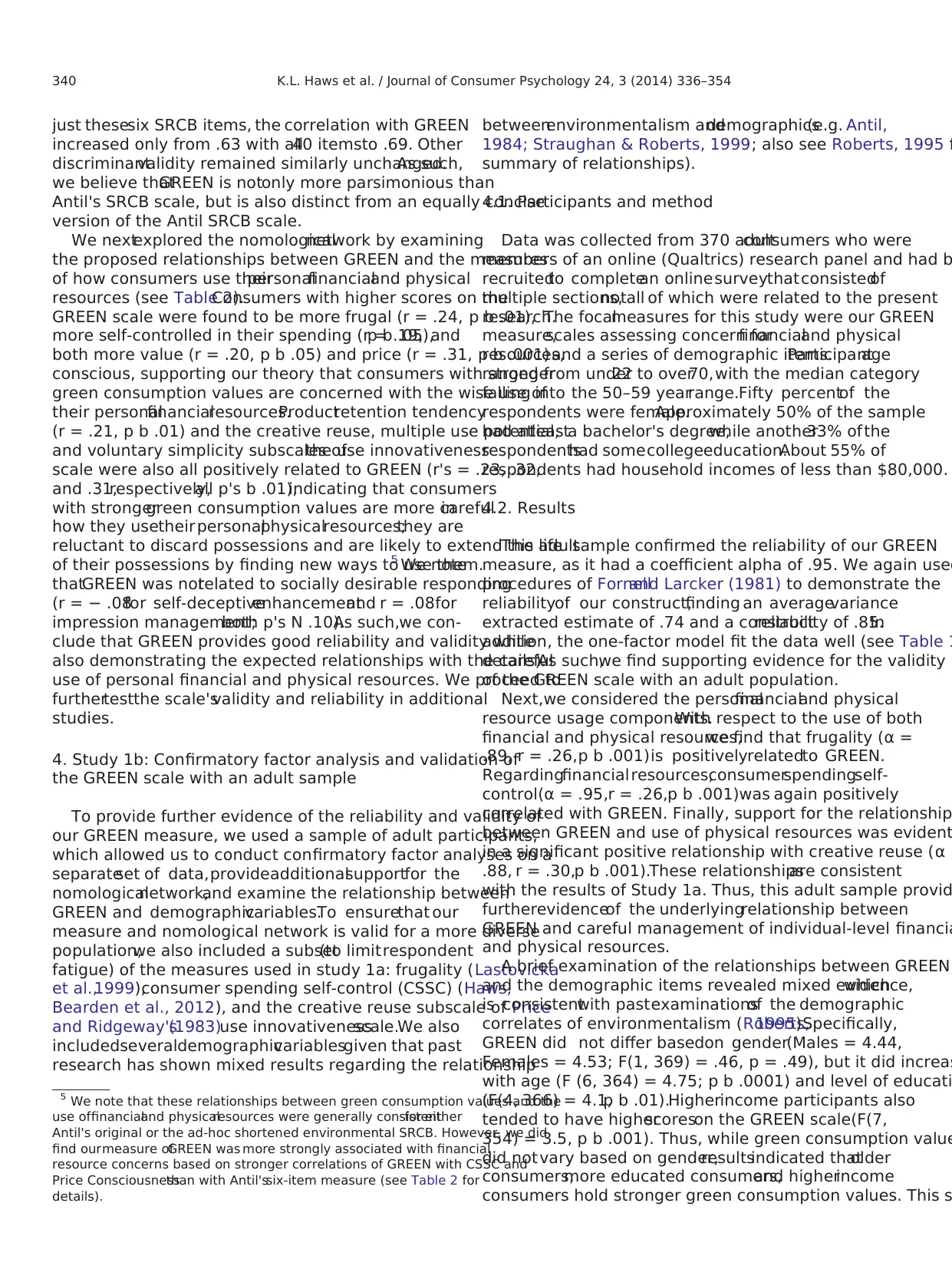

Table 1

Study 1a–1d: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Factor loading estimates

GREEN items Study

1a

Study

1b

Study

1c

Study

1d

It is important to me that the products

I use do not harm the

environment.

.73 .86 .73 .73

I consider the potential

environmental

impact of my actions when

making many of my decisions.

.81 .91 .81 .80

My purchase habits are affected by

my concern for our environment.

.78 .90 .77 .79

I am concerned about wasting the

resources of our planet.

.75 .86 .76 .79

I would describe myself as

environmentally responsible.

.78 .82 .77 .75

I am willing to be inconvenienced

in order to take actions

that are more environmentally

friendly.

.83 .82 .83 .83

Fit statistics

Comparative fit index (CFI) .96 .96 .96 .96

Normed fit index (NFI) .95 .96 .96 .96

Standardized root mean

residual (SRMR)

.05 .04 .05 .04

Χ 2, 9 df 72.6 156.4 56.1 57.3

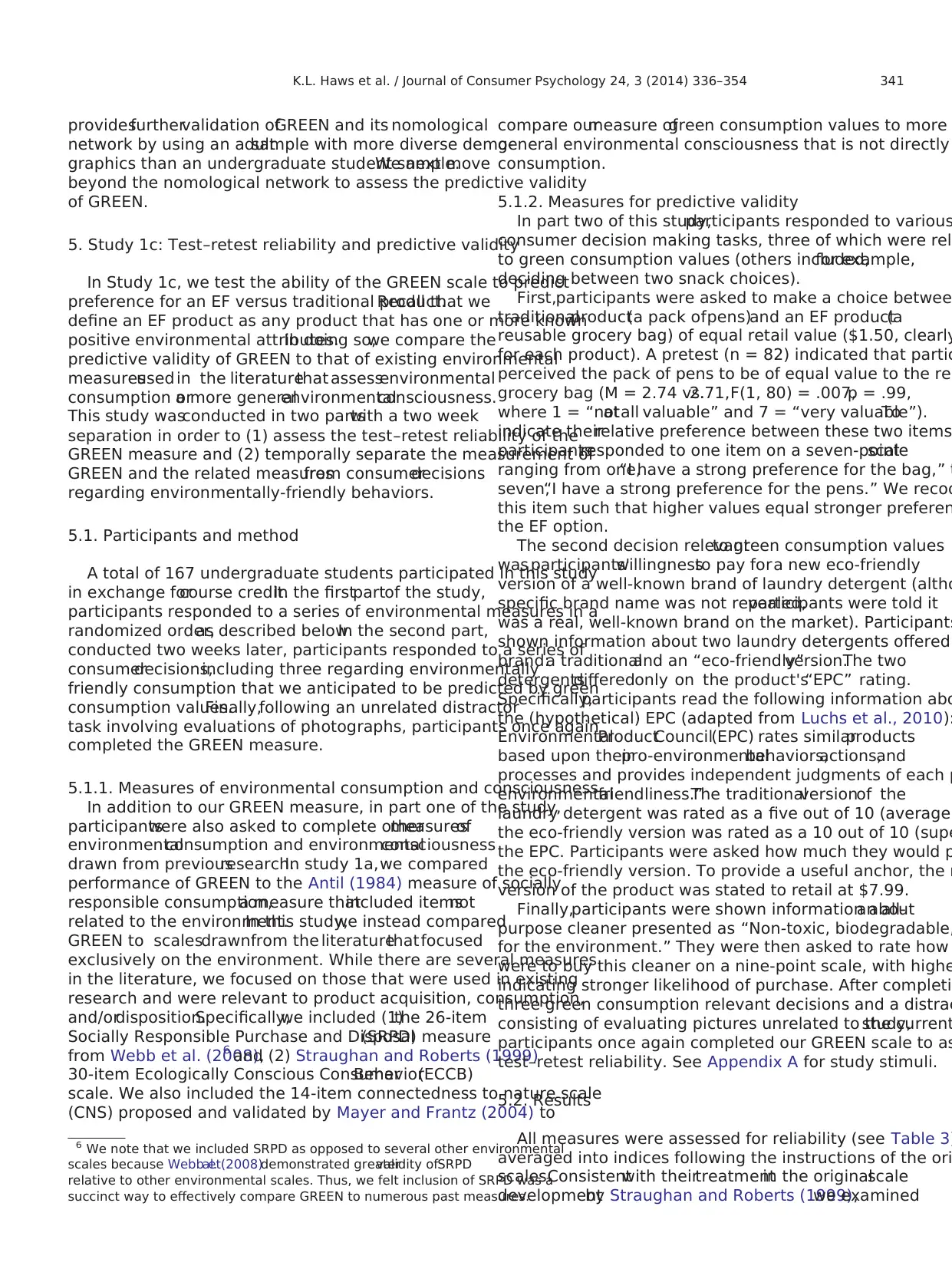

Table 2

Summary of correlations among green and consumer measures, study 1a.

Alpha Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. Green .89 3.95 .67

2. SRCB .88 3.96 1.19 .63

3. Short SRCB .87 3.99 1.17 .69 .85

4. Frugality .82 5.14 1.19 .24 .21 .29

5. CSSC .94 5.57 .82 .19 .08 .13 .66

6. Value consciousness .87 3.56 1.27 .20 .21 .21 .49 .42

7. Price consciousness .83 5.46 1.10 .31 .27 .29 .40 .30 .49

8. PRT .93 4.66 1.58 .21 .20 .25 .20 .11 .17 .11

9. Creative reuse .54 3.25 1.10 .23 .25 .26 .27 .18 .41 .24 .30

10. Multiple use .64 4.15 .94 .32 .26 .28 .30 .25 .27 .31 .39 .68

11. Voluntary simplicity .89 4.16 1.27 .31 .22 .29 .25 .20 .24 .24 .26 .48 .56

Note.All correlations of .14 or greater are significantat p b .05.SRCB is Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior from Antil(1984);ShortSRCB is six

environmental items from Antil's SRCB; Frugality (Lastovicka et al., 1999); CSSC is consumer spending self-control from Haws, Bearden, et

price consciousness are from Lichtenstein et al. (1990); PRT is product retention tendency from Haws, Naylor, et al. (2012); and creative re

voluntary simplicity are from use innovativeness by Price and Ridgeway (1983).

339K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

recommendations by Bearden, Netemeyer, and Haws (2010) and

Bearden,Netemeyer,and Teel(1989).This process led to the

elimination of four items.Accordingly,we determined thatthe

remaining six items were highly reliable (α = .89)and could

succinctly capture the green construct (See Table 1 for final items).

Confirmatory factoranalysis using the six items demonstrated

strong fit of the model (see Table 1). Procedures recommended by

Fornelland Larcker(1981)showed:(1) the average variance

extracted (.61) exceeded the recommended value of .50 and (2)

constructreliability (.90)also implied a good fitting model.

From both a managerialand a research perspective,the most

parsimoniousmeasurepossiblethat still capturesthe core

constructfully is the mostuseful(Haws,Nayloret al.,2012;

Richins, 2004).

With this six-item scale,we proceeded to analyzethe

relationships with Antil's SRCB and other constructs theo

as part of the nomological network. All existing measures

assessed for reliability and averaged into indices followin

instructions of the original scales, except for price consci

which was reverse-coded, such that higher values indicat

price consciousness, to be consistent with the other mea

descriptive statistics and correlations among constructs a

shown in Table 2. As expected, GREEN was highly correla

with Antil'sSRCB index (r = .63,p b .0001).This strong

correlation notonly provides evidence ofthe validity ofour

measure but also suggests that our six-item measure suffi

captures the contentof the 40-item SRCB.However,we also

expected the two measures to show distinction.Confirmatory

factor analysis revealed a phi coefficient of .46 between G

and SRCB. Comparison of the AVE estimates with the squ

phi coefficient reflecting the correlation between the mea

GREEN and SRCB provided additional evidence of discrim

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988). A chi-square difference test comparing a one-facto

to a two-factorcorrelated modelalso supported discriminant

validitybetweenGREEN and SRCB (Δχ 2(1) = 5168.25,

p b .001),while the corresponding RMSEA decreased from

0.16 to 0.07 (lowerscores indicate a betterfit; Anderson &

Gerbing, 1988).

One possibilityis that Antil's SRCB index is more

comprehensive than ourfocus on green consumption values

and a subset of these items would be more representativ

scale's environmental and consumption focus.Though Antil's

SRCB index is one-dimensional,we conducteda factor

analysisto determine the six itemsthatwere mostclosely

associated with ourGREEN scale.All six of theseitems

concerned the environmentand notothersocialissues;for

example:“All consumers should be interested in the enviro

mentalconsequencesof the productsthey purchase”(see

Appendix A for all items). Using this ad-hoc index created

Table 1

Study 1a–1d: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Factor loading estimates

GREEN items Study

1a

Study

1b

Study

1c

Study

1d

It is important to me that the products

I use do not harm the

environment.

.73 .86 .73 .73

I consider the potential

environmental

impact of my actions when

making many of my decisions.

.81 .91 .81 .80

My purchase habits are affected by

my concern for our environment.

.78 .90 .77 .79

I am concerned about wasting the

resources of our planet.

.75 .86 .76 .79

I would describe myself as

environmentally responsible.

.78 .82 .77 .75

I am willing to be inconvenienced

in order to take actions

that are more environmentally

friendly.

.83 .82 .83 .83

Fit statistics

Comparative fit index (CFI) .96 .96 .96 .96

Normed fit index (NFI) .95 .96 .96 .96

Standardized root mean

residual (SRMR)

.05 .04 .05 .04

Χ 2, 9 df 72.6 156.4 56.1 57.3

Table 2

Summary of correlations among green and consumer measures, study 1a.

Alpha Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. Green .89 3.95 .67

2. SRCB .88 3.96 1.19 .63

3. Short SRCB .87 3.99 1.17 .69 .85

4. Frugality .82 5.14 1.19 .24 .21 .29

5. CSSC .94 5.57 .82 .19 .08 .13 .66

6. Value consciousness .87 3.56 1.27 .20 .21 .21 .49 .42

7. Price consciousness .83 5.46 1.10 .31 .27 .29 .40 .30 .49

8. PRT .93 4.66 1.58 .21 .20 .25 .20 .11 .17 .11

9. Creative reuse .54 3.25 1.10 .23 .25 .26 .27 .18 .41 .24 .30

10. Multiple use .64 4.15 .94 .32 .26 .28 .30 .25 .27 .31 .39 .68

11. Voluntary simplicity .89 4.16 1.27 .31 .22 .29 .25 .20 .24 .24 .26 .48 .56

Note.All correlations of .14 or greater are significantat p b .05.SRCB is Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior from Antil(1984);ShortSRCB is six

environmental items from Antil's SRCB; Frugality (Lastovicka et al., 1999); CSSC is consumer spending self-control from Haws, Bearden, et

price consciousness are from Lichtenstein et al. (1990); PRT is product retention tendency from Haws, Naylor, et al. (2012); and creative re

voluntary simplicity are from use innovativeness by Price and Ridgeway (1983).

339K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

just thesesix SRCB items, the correlation with GREEN

increased only from .63 with all40 itemsto .69. Other

discriminantvalidity remained similarly unchanged.As such,

we believe thatGREEN is notonly more parsimonious than

Antil's SRCB scale, but is also distinct from an equally concise

version of the Antil SRCB scale.

We nextexplored the nomologicalnetwork by examining

the proposed relationships between GREEN and the measures

of how consumers use theirpersonalfinancialand physical

resources (see Table 2).Consumers with higher scores on the

GREEN scale were found to be more frugal (r = .24, p b .01),

more self-controlled in their spending (r = .19,p b .05),and

both more value (r = .20, p b .05) and price (r = .31, p b .001)

conscious, supporting our theory that consumers with stronger

green consumption values are concerned with the wise use of

their personalfinancialresources.Productretention tendency

(r = .21, p b .01) and the creative reuse, multiple use potential,

and voluntary simplicity subscales ofthe use innovativeness

scale were also all positively related to GREEN (r's = .23, .32,

and .31,respectively,all p's b .01),indicating that consumers

with strongergreen consumption values are more carefulin

how they usetheir personalphysicalresources;they are

reluctant to discard possessions and are likely to extend the life

of their possessions by finding new ways to use them.5 We note

thatGREEN was notrelated to socially desirable responding

(r = − .08for self-deceptiveenhancementand r = .08for

impression management;both p's N .10).As such,we con-

clude that GREEN provides good reliability and validity while

also demonstrating the expected relationships with the careful

use of personal financial and physical resources. We proceed to

furthertestthe scale'svalidity and reliability in additional

studies.

4. Study 1b: Confirmatory factor analysis and validation of

the GREEN scale with an adult sample

To provide further evidence of the reliability and validity of

our GREEN measure, we used a sample of adult participants,

which allowed us to conduct confirmatory factor analyses on a

separateset of data,provideadditionalsupportfor the

nomologicalnetwork,and examine the relationship between

GREEN and demographicvariables.To ensurethat our

measure and nomological network is valid for a more diverse

population,we also included a subset(to limitrespondent

fatigue) of the measures used in study 1a: frugality (Lastovicka

et al.,1999),consumer spending self-control (CSSC) (Haws,

Bearden et al., 2012), and the creative reuse subscale of Price

and Ridgeway's(1983)use innovativenessscale.We also

includedseveraldemographicvariablesgiven that past

research has shown mixed results regarding the relationship

betweenenvironmentalism anddemographics(e.g. Antil,

1984; Straughan & Roberts, 1999; also see Roberts, 1995 f

summary of relationships).

4.1. Participants and method

Data was collected from 370 adultconsumers who were

members of an online (Qualtrics) research panel and had b

recruitedto completean onlinesurveythatconsistedof

multiple sections,notall of which were related to the present

research.The focalmeasures for this study were our GREEN

measure,scales assessing concern forfinancialand physical

resources,and a series of demographic items.Participantage

ranged from under22 to over70,with the median category

falling into the 50–59 yearrange.Fifty percentof the

respondents were female.Approximately 50% of the sample

had atleasta bachelor's degree,while another33% of the

respondentshad somecollegeeducation.About 55% of

respondents had household incomes of less than $80,000.

4.2. Results

This adultsample confirmed the reliability of our GREEN

measure, as it had a coefficient alpha of .95. We again used

procedures of Fornelland Larcker (1981) to demonstrate the

reliabilityof our construct,finding an averagevariance

extracted estimate of .74 and a constructreliability of .85.In

addition, the one-factor model fit the data well (see Table 1

details).As such,we find supporting evidence for the validity

of the GREEN scale with an adult population.

Next,we considered the personalfinancialand physical

resource usage components.With respect to the use of both

financial and physical resources,we find that frugality (α =

.89, r = .26,p b .001)is positivelyrelatedto GREEN.

Regardingfinancialresources,consumerspendingself-

control(α = .95,r = .26,p b .001)was again positively

correlated with GREEN. Finally, support for the relationship

between GREEN and use of physical resources was evident

in a significant positive relationship with creative reuse (α =

.88, r = .30,p b .001).These relationshipsare consistent

with the results of Study 1a. Thus, this adult sample provid

furtherevidenceof the underlyingrelationship between

GREEN and careful management of individual-level financia

and physical resources.

A brief examination of the relationships between GREEN

and the demographic items revealed mixed evidence,which

is consistentwith pastexaminationsof the demographic

correlates of environmentalism (Roberts,1995).Specifically,

GREEN did not differ basedon gender(Males = 4.44,

Females = 4.53; F(1, 369) = .46, p = .49), but it did increas

with age (F (6, 364) = 4.75; p b .0001) and level of educati

(F(4, 366) = 4.1,p b .01).Higherincome participants also

tended to have higherscoreson the GREEN scale(F(7,

354) = 3.5, p b .001). Thus, while green consumption value

did not vary based on gender,resultsindicated thatolder

consumers,more educated consumers,and higherincome

consumers hold stronger green consumption values. This s

5 We note that these relationships between green consumption values and the

use offinancialand physicalresources were generally consistentfor either

Antil's original or the ad-hoc shortened environmental SRCB. However, we did

find ourmeasure ofGREEN was more strongly associated with financial

resource concerns based on stronger correlations of GREEN with CSSC and

Price Consciousnessthan with Antil'ssix-item measure (see Table 2 for

details).

340 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

increased only from .63 with all40 itemsto .69. Other

discriminantvalidity remained similarly unchanged.As such,

we believe thatGREEN is notonly more parsimonious than

Antil's SRCB scale, but is also distinct from an equally concise

version of the Antil SRCB scale.

We nextexplored the nomologicalnetwork by examining

the proposed relationships between GREEN and the measures

of how consumers use theirpersonalfinancialand physical

resources (see Table 2).Consumers with higher scores on the

GREEN scale were found to be more frugal (r = .24, p b .01),

more self-controlled in their spending (r = .19,p b .05),and

both more value (r = .20, p b .05) and price (r = .31, p b .001)

conscious, supporting our theory that consumers with stronger

green consumption values are concerned with the wise use of

their personalfinancialresources.Productretention tendency

(r = .21, p b .01) and the creative reuse, multiple use potential,

and voluntary simplicity subscales ofthe use innovativeness

scale were also all positively related to GREEN (r's = .23, .32,

and .31,respectively,all p's b .01),indicating that consumers

with strongergreen consumption values are more carefulin

how they usetheir personalphysicalresources;they are

reluctant to discard possessions and are likely to extend the life

of their possessions by finding new ways to use them.5 We note

thatGREEN was notrelated to socially desirable responding

(r = − .08for self-deceptiveenhancementand r = .08for

impression management;both p's N .10).As such,we con-

clude that GREEN provides good reliability and validity while

also demonstrating the expected relationships with the careful

use of personal financial and physical resources. We proceed to

furthertestthe scale'svalidity and reliability in additional

studies.

4. Study 1b: Confirmatory factor analysis and validation of

the GREEN scale with an adult sample

To provide further evidence of the reliability and validity of

our GREEN measure, we used a sample of adult participants,

which allowed us to conduct confirmatory factor analyses on a

separateset of data,provideadditionalsupportfor the

nomologicalnetwork,and examine the relationship between

GREEN and demographicvariables.To ensurethat our

measure and nomological network is valid for a more diverse

population,we also included a subset(to limitrespondent

fatigue) of the measures used in study 1a: frugality (Lastovicka

et al.,1999),consumer spending self-control (CSSC) (Haws,

Bearden et al., 2012), and the creative reuse subscale of Price

and Ridgeway's(1983)use innovativenessscale.We also

includedseveraldemographicvariablesgiven that past

research has shown mixed results regarding the relationship

betweenenvironmentalism anddemographics(e.g. Antil,

1984; Straughan & Roberts, 1999; also see Roberts, 1995 f

summary of relationships).

4.1. Participants and method

Data was collected from 370 adultconsumers who were

members of an online (Qualtrics) research panel and had b

recruitedto completean onlinesurveythatconsistedof

multiple sections,notall of which were related to the present

research.The focalmeasures for this study were our GREEN

measure,scales assessing concern forfinancialand physical

resources,and a series of demographic items.Participantage

ranged from under22 to over70,with the median category

falling into the 50–59 yearrange.Fifty percentof the

respondents were female.Approximately 50% of the sample

had atleasta bachelor's degree,while another33% of the

respondentshad somecollegeeducation.About 55% of

respondents had household incomes of less than $80,000.

4.2. Results

This adultsample confirmed the reliability of our GREEN

measure, as it had a coefficient alpha of .95. We again used

procedures of Fornelland Larcker (1981) to demonstrate the

reliabilityof our construct,finding an averagevariance

extracted estimate of .74 and a constructreliability of .85.In

addition, the one-factor model fit the data well (see Table 1

details).As such,we find supporting evidence for the validity

of the GREEN scale with an adult population.

Next,we considered the personalfinancialand physical

resource usage components.With respect to the use of both

financial and physical resources,we find that frugality (α =

.89, r = .26,p b .001)is positivelyrelatedto GREEN.

Regardingfinancialresources,consumerspendingself-

control(α = .95,r = .26,p b .001)was again positively

correlated with GREEN. Finally, support for the relationship

between GREEN and use of physical resources was evident

in a significant positive relationship with creative reuse (α =

.88, r = .30,p b .001).These relationshipsare consistent

with the results of Study 1a. Thus, this adult sample provid

furtherevidenceof the underlyingrelationship between

GREEN and careful management of individual-level financia

and physical resources.

A brief examination of the relationships between GREEN

and the demographic items revealed mixed evidence,which

is consistentwith pastexaminationsof the demographic

correlates of environmentalism (Roberts,1995).Specifically,

GREEN did not differ basedon gender(Males = 4.44,

Females = 4.53; F(1, 369) = .46, p = .49), but it did increas

with age (F (6, 364) = 4.75; p b .0001) and level of educati

(F(4, 366) = 4.1,p b .01).Higherincome participants also

tended to have higherscoreson the GREEN scale(F(7,

354) = 3.5, p b .001). Thus, while green consumption value

did not vary based on gender,resultsindicated thatolder

consumers,more educated consumers,and higherincome

consumers hold stronger green consumption values. This s

5 We note that these relationships between green consumption values and the

use offinancialand physicalresources were generally consistentfor either

Antil's original or the ad-hoc shortened environmental SRCB. However, we did

find ourmeasure ofGREEN was more strongly associated with financial

resource concerns based on stronger correlations of GREEN with CSSC and

Price Consciousnessthan with Antil'ssix-item measure (see Table 2 for

details).

340 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

providesfurthervalidation ofGREEN and its nomological

network by using an adultsample with more diverse demo-

graphics than an undergraduate student sample.We next move

beyond the nomological network to assess the predictive validity

of GREEN.

5. Study 1c: Test–retest reliability and predictive validity

In Study 1c, we test the ability of the GREEN scale to predict

preference for an EF versus traditional product.Recall that we

define an EF product as any product that has one or more known

positive environmental attributes.In doing so,we compare the

predictive validity of GREEN to that of existing environmental

measuresused in the literaturethat assessenvironmental

consumption ora more generalenvironmentalconsciousness.

This study wasconducted in two partswith a two week

separation in order to (1) assess the test–retest reliability of the

GREEN measure and (2) temporally separate the measurement of

GREEN and the related measuresfrom consumerdecisions

regarding environmentally-friendly behaviors.

5.1. Participants and method

A total of 167 undergraduate students participated in this study

in exchange forcourse credit.In the firstpartof the study,

participants responded to a series of environmental measures in a

randomized order,as described below.In the second part,

conducted two weeks later, participants responded to a series of

consumerdecisions,including three regarding environmentally

friendly consumption that we anticipated to be predicted by green

consumption values.Finally,following an unrelated distractor

task involving evaluations of photographs, participants once again

completed the GREEN measure.

5.1.1. Measures of environmental consumption and consciousness

In addition to our GREEN measure, in part one of the study,

participantswere also asked to complete othermeasuresof

environmentalconsumption and environmentalconsciousness

drawn from previousresearch.In study 1a,we compared

performance of GREEN to the Antil (1984) measure of socially

responsible consumption,a measure thatincluded itemsnot

related to the environment.In this study,we instead compared

GREEN to scalesdrawnfrom the literaturethatfocused

exclusively on the environment. While there are several measures

in the literature, we focused on those that were used in existing

research and were relevant to product acquisition, consumption,

and/ordisposition.Specifically,we included (1)the 26-item

Socially Responsible Purchase and Disposal(SRPD) measure

from Webb et al. (2008),6 and (2) Straughan and Roberts (1999)

30-item Ecologically Conscious ConsumerBehavior(ECCB)

scale. We also included the 14-item connectedness to nature scale

(CNS) proposed and validated by Mayer and Frantz (2004) to

compare ourmeasure ofgreen consumption values to more

general environmental consciousness that is not directly

consumption.

5.1.2. Measures for predictive validity

In part two of this study,participants responded to various

consumer decision making tasks, three of which were rel

to green consumption values (others included,for example,

deciding between two snack choices).

First,participants were asked to make a choice betwee

traditionalproduct(a pack ofpens)and an EF product(a

reusable grocery bag) of equal retail value ($1.50, clearly

for each product). A pretest (n = 82) indicated that partic

perceived the pack of pens to be of equal value to the reu

grocery bag (M = 2.74 vs.2.71,F(1, 80) = .007,p = .99,

where 1 = “notatall valuable” and 7 = “very valuable”).To

indicate theirrelative preference between these two items

participantsresponded to one item on a seven-pointscale

ranging from one,“I have a strong preference for the bag,” t

seven,“I have a strong preference for the pens.” We recod

this item such that higher values equal stronger preferen

the EF option.

The second decision relevantto green consumption values

was participants'willingnessto pay fora new eco-friendly

version of a well-known brand of laundry detergent (altho

specific brand name was not revealed,participants were told it

was a real, well-known brand on the market). Participants

shown information about two laundry detergents offered

brand:a traditionaland an “eco-friendly”version.The two

detergentsdifferedonly on the product's“EPC” rating.

Specifically,participants read the following information abo

the (hypothetical) EPC (adapted from Luchs et al., 2010):

EnvironmentalProductCouncil(EPC) rates similarproducts

based upon theirpro-environmentalbehaviors,actions,and

processes and provides independent judgments of each p

environmentalfriendliness.”The traditionalversionof the

laundry detergent was rated as a five out of 10 (average)

the eco-friendly version was rated as a 10 out of 10 (supe

the EPC. Participants were asked how much they would p

the eco-friendly version. To provide a useful anchor, the r

version of the product was stated to retail at $7.99.

Finally,participants were shown information aboutan all-

purpose cleaner presented as “Non-toxic, biodegradable,

for the environment.” They were then asked to rate how

were to buy this cleaner on a nine-point scale, with highe

indicating stronger likelihood of purchase. After completi

three green consumption relevant decisions and a distrac

consisting of evaluating pictures unrelated to the currentstudy,

participants once again completed our GREEN scale to as

test–retest reliability. See Appendix A for study stimuli.

5.2. Results

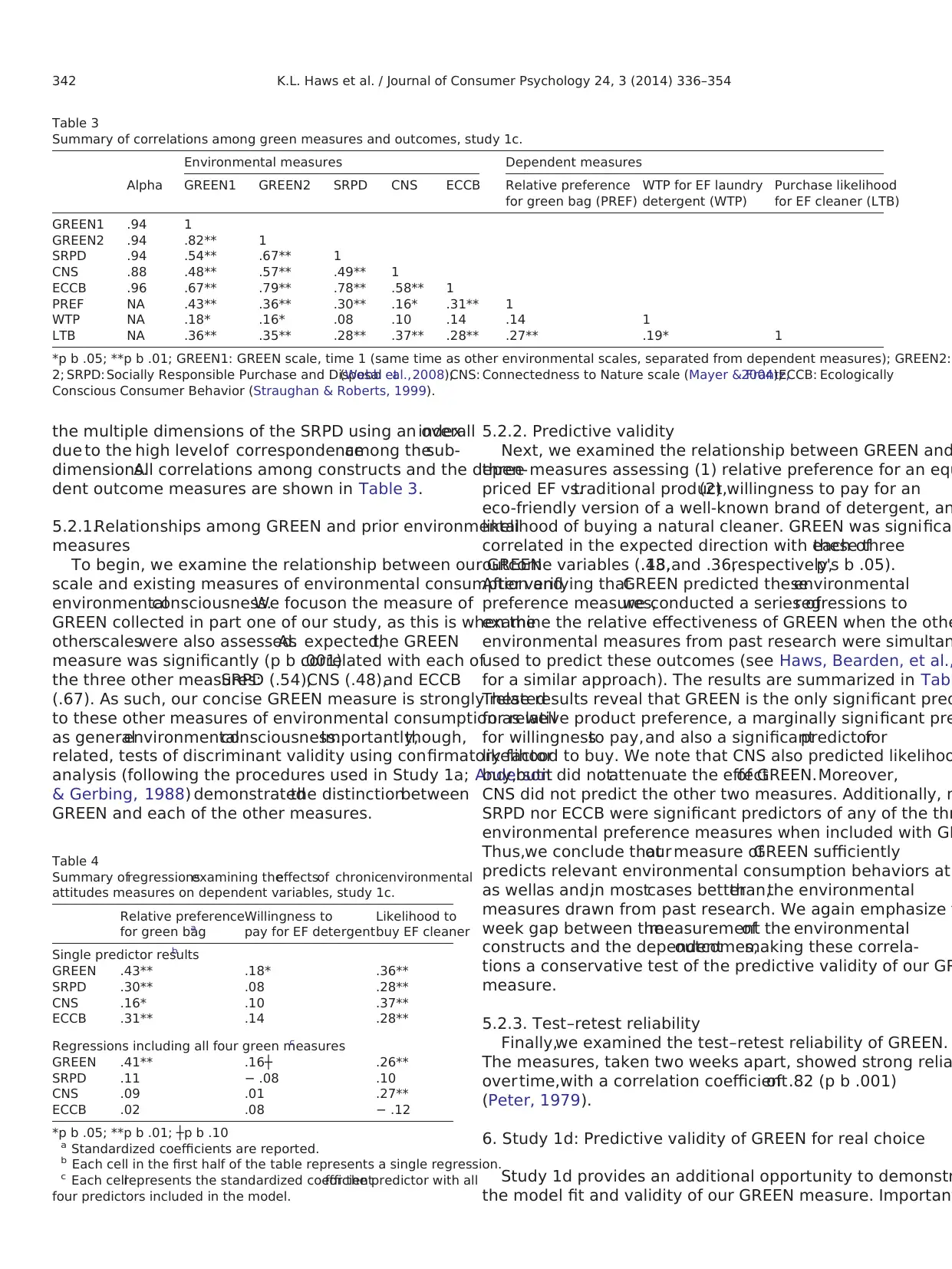

All measures were assessed for reliability (see Table 3)

averaged into indices following the instructions of the ori

scales.Consistentwith theirtreatmentin the originalscale

developmentby Straughan and Roberts (1999),we examined

6 We note that we included SRPD as opposed to several other environmental

scales because Webb etal. (2008)demonstrated greatervalidity ofSRPD

relative to other environmental scales. Thus, we felt inclusion of SRPD was a

succinct way to effectively compare GREEN to numerous past measures.

341K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

network by using an adultsample with more diverse demo-

graphics than an undergraduate student sample.We next move

beyond the nomological network to assess the predictive validity

of GREEN.

5. Study 1c: Test–retest reliability and predictive validity

In Study 1c, we test the ability of the GREEN scale to predict

preference for an EF versus traditional product.Recall that we

define an EF product as any product that has one or more known

positive environmental attributes.In doing so,we compare the

predictive validity of GREEN to that of existing environmental

measuresused in the literaturethat assessenvironmental

consumption ora more generalenvironmentalconsciousness.

This study wasconducted in two partswith a two week

separation in order to (1) assess the test–retest reliability of the

GREEN measure and (2) temporally separate the measurement of

GREEN and the related measuresfrom consumerdecisions

regarding environmentally-friendly behaviors.

5.1. Participants and method

A total of 167 undergraduate students participated in this study

in exchange forcourse credit.In the firstpartof the study,

participants responded to a series of environmental measures in a

randomized order,as described below.In the second part,

conducted two weeks later, participants responded to a series of

consumerdecisions,including three regarding environmentally

friendly consumption that we anticipated to be predicted by green

consumption values.Finally,following an unrelated distractor

task involving evaluations of photographs, participants once again

completed the GREEN measure.

5.1.1. Measures of environmental consumption and consciousness

In addition to our GREEN measure, in part one of the study,

participantswere also asked to complete othermeasuresof

environmentalconsumption and environmentalconsciousness

drawn from previousresearch.In study 1a,we compared

performance of GREEN to the Antil (1984) measure of socially

responsible consumption,a measure thatincluded itemsnot

related to the environment.In this study,we instead compared

GREEN to scalesdrawnfrom the literaturethatfocused

exclusively on the environment. While there are several measures

in the literature, we focused on those that were used in existing

research and were relevant to product acquisition, consumption,

and/ordisposition.Specifically,we included (1)the 26-item

Socially Responsible Purchase and Disposal(SRPD) measure

from Webb et al. (2008),6 and (2) Straughan and Roberts (1999)

30-item Ecologically Conscious ConsumerBehavior(ECCB)

scale. We also included the 14-item connectedness to nature scale

(CNS) proposed and validated by Mayer and Frantz (2004) to

compare ourmeasure ofgreen consumption values to more

general environmental consciousness that is not directly

consumption.

5.1.2. Measures for predictive validity

In part two of this study,participants responded to various

consumer decision making tasks, three of which were rel

to green consumption values (others included,for example,

deciding between two snack choices).

First,participants were asked to make a choice betwee

traditionalproduct(a pack ofpens)and an EF product(a

reusable grocery bag) of equal retail value ($1.50, clearly

for each product). A pretest (n = 82) indicated that partic

perceived the pack of pens to be of equal value to the reu

grocery bag (M = 2.74 vs.2.71,F(1, 80) = .007,p = .99,

where 1 = “notatall valuable” and 7 = “very valuable”).To

indicate theirrelative preference between these two items

participantsresponded to one item on a seven-pointscale

ranging from one,“I have a strong preference for the bag,” t

seven,“I have a strong preference for the pens.” We recod

this item such that higher values equal stronger preferen

the EF option.

The second decision relevantto green consumption values

was participants'willingnessto pay fora new eco-friendly

version of a well-known brand of laundry detergent (altho

specific brand name was not revealed,participants were told it

was a real, well-known brand on the market). Participants

shown information about two laundry detergents offered

brand:a traditionaland an “eco-friendly”version.The two

detergentsdifferedonly on the product's“EPC” rating.

Specifically,participants read the following information abo

the (hypothetical) EPC (adapted from Luchs et al., 2010):

EnvironmentalProductCouncil(EPC) rates similarproducts

based upon theirpro-environmentalbehaviors,actions,and

processes and provides independent judgments of each p

environmentalfriendliness.”The traditionalversionof the

laundry detergent was rated as a five out of 10 (average)

the eco-friendly version was rated as a 10 out of 10 (supe

the EPC. Participants were asked how much they would p

the eco-friendly version. To provide a useful anchor, the r

version of the product was stated to retail at $7.99.

Finally,participants were shown information aboutan all-

purpose cleaner presented as “Non-toxic, biodegradable,

for the environment.” They were then asked to rate how

were to buy this cleaner on a nine-point scale, with highe

indicating stronger likelihood of purchase. After completi

three green consumption relevant decisions and a distrac

consisting of evaluating pictures unrelated to the currentstudy,

participants once again completed our GREEN scale to as

test–retest reliability. See Appendix A for study stimuli.

5.2. Results

All measures were assessed for reliability (see Table 3)

averaged into indices following the instructions of the ori

scales.Consistentwith theirtreatmentin the originalscale

developmentby Straughan and Roberts (1999),we examined

6 We note that we included SRPD as opposed to several other environmental

scales because Webb etal. (2008)demonstrated greatervalidity ofSRPD

relative to other environmental scales. Thus, we felt inclusion of SRPD was a

succinct way to effectively compare GREEN to numerous past measures.

341K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

the multiple dimensions of the SRPD using an overallindex

due to the high levelof correspondenceamong thesub-

dimensions.All correlations among constructs and the depen-

dent outcome measures are shown in Table 3.

5.2.1.Relationships among GREEN and prior environmental

measures

To begin, we examine the relationship between our GREEN

scale and existing measures of environmental consumption and

environmentalconsciousness.We focuson the measure of

GREEN collected in part one of our study, as this is when the

otherscaleswere also assessed.As expected,the GREEN

measure was significantly (p b .001)correlated with each of

the three other measures:SRPD (.54),CNS (.48),and ECCB

(.67). As such, our concise GREEN measure is strongly related

to these other measures of environmental consumption as well

as generalenvironmentalconsciousness.Importantly,though,

related, tests of discriminant validity using confirmatory factor

analysis (following the procedures used in Study 1a; Anderson

& Gerbing, 1988) demonstratedthe distinctionbetween

GREEN and each of the other measures.

5.2.2. Predictive validity

Next, we examined the relationship between GREEN and

three measures assessing (1) relative preference for an equ

priced EF vs.traditional product,(2) willingness to pay for an

eco-friendly version of a well-known brand of detergent, an

likelihood of buying a natural cleaner. GREEN was significa

correlated in the expected direction with each ofthese three

outcome variables (.43,.18,and .36,respectively,p's b .05).

After verifying thatGREEN predicted theseenvironmental

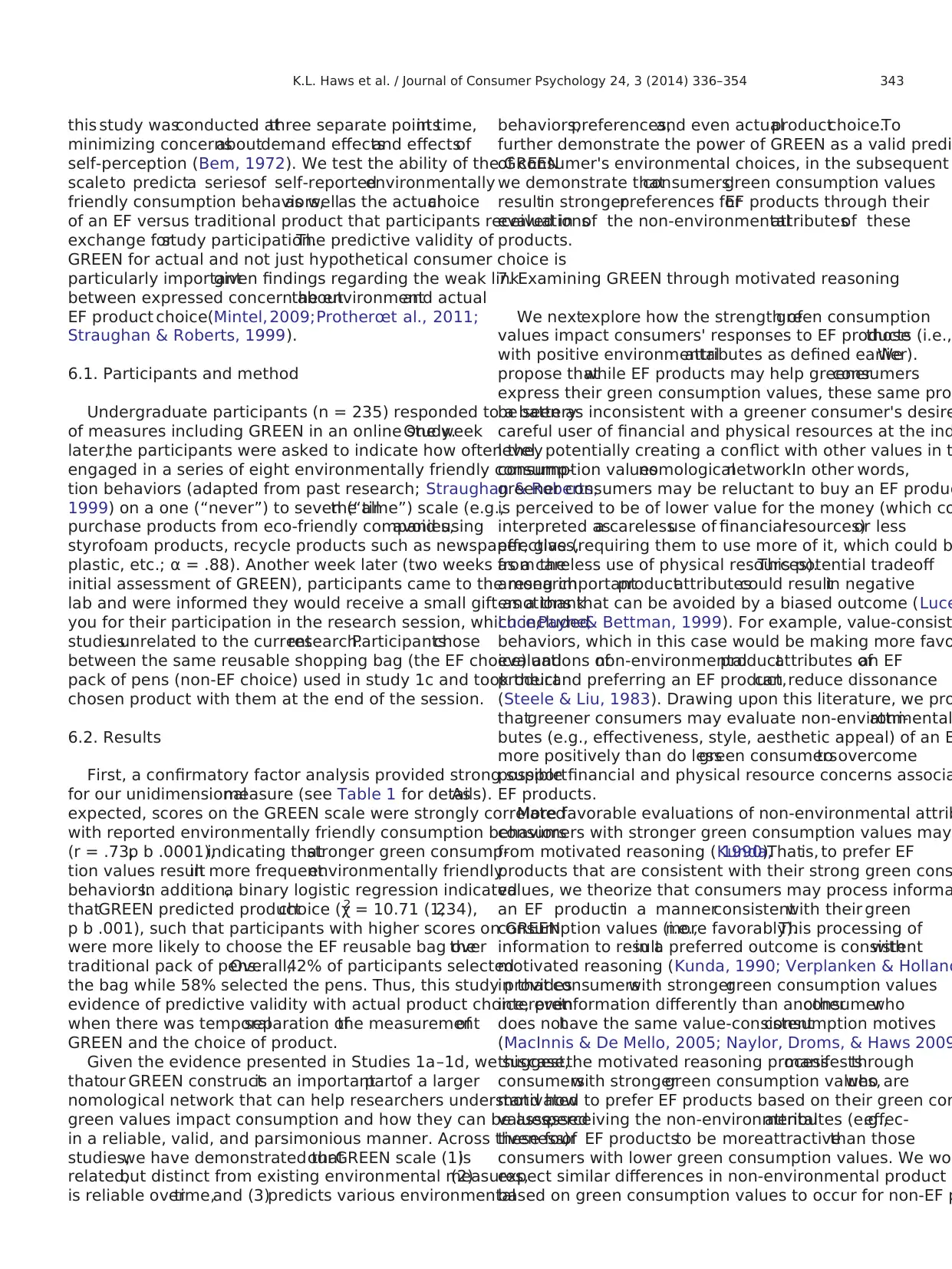

preference measures,we conducted a series ofregressions to

examine the relative effectiveness of GREEN when the othe

environmental measures from past research were simultan

used to predict these outcomes (see Haws, Bearden, et al.,

for a similar approach). The results are summarized in Tabl

These results reveal that GREEN is the only significant pred

for relative product preference, a marginally significant pre

for willingnessto pay,and also a significantpredictorfor

likelihood to buy. We note that CNS also predicted likelihoo

buy,butit did notattenuate the effectof GREEN.Moreover,

CNS did not predict the other two measures. Additionally, n

SRPD nor ECCB were significant predictors of any of the thr

environmental preference measures when included with GR

Thus,we conclude thatour measure ofGREEN sufficiently