A Literature Review on Virtual Teams, Leadership, and Team Performance

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/20

|24

|12500

|342

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review explores the evolving landscape of virtual teams, examining the impact of leadership, structural supports, and shared leadership on team performance. It delves into the challenges and advantages of virtual teams, highlighting the shift from traditional face-to-face interactions to predominantly electronic communication. The review discusses the importance of team virtuality, encompassing geographic distribution, e-communication media usage, and cultural diversity. It analyzes the role of hierarchical leadership and the need for supplementary structural supports and shared leadership in enhancing team performance. The document emphasizes the complexities of leading virtual teams and the need for adapting leadership strategies to the virtual environment, discussing potential indicators of virtuality and the advantages and challenges at individual, organizational, and societal levels. The review also addresses the impact of cultural diversity on team dynamics and calls for considering these differences in conceptualizations of virtuality.

Literature Review

Distributed work across different locations and/or working times is not a phenomenon of the

last 15 years. There are many instructive examples of how people collaborated across larger

distances in earlier times (King & Frost, 2002; O’Leary, Orlikowski, & Yates, 2002).

However, with the rapid development of electronic information and communication media in

the last years, distributed work has become much easier, faster and more efficient. The first is

telework (telecommuting) which is done partially or completely outside of the main company

workplace with the aid of information and telecommunication services (Bailey & Kurland,

2002; Konradt, Schmook, & Ma¨lecke, 2000). Virtual groups exists when several teleworkers

are combined and each member reports to the same manager. In contrast, a virtual team exists

when the members of a virtual group interact with each other in order to accomplish common

goals (Lipnack & Stamps, 1997). This distinction between virtual group and virtual team is

parallel to the distinction between conventional groups and teams in the organizational

literature (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003). Finally, virtual communities are larger entities of

distributed work in which members participate via the Internet, guided by common purposes,

roles and norms. In contrast to virtual teams, virtual communities are not implemented within

an organizational structure but are usually initiated by some of their members. Examples of

virtual communities are Open Source software projects (Hertel, Niedner, & Herrmann, 2003;

Moon & Sproull, 2002) or scientific collaboratories (Finholt, 2002). For reasons of

feasibility, the current review is restricted to virtual teams. Apart from these more general

differentiations, the more specific definition of virtual teams is still controversial (Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Griffith & Neale, 2000; Maznevski & Chudoba, 2000). As a minimal

consensus, virtual teams consist of (a) two or more persons who (b) collaborate interactively

to achieve common goals, while (c) at least one of the team members works at a different

location, organization, or at a different time so that (d) communication and coordination is

predominantly based on electronic communication media (email, fax, phone, video

conference, etc.). It is important to note that the latter two aspects in this definition are

considered as dimensions rather than as dichotomized criteria that distinguish virtual teams

from conventional face-to-face teams. While extreme cases of virtual teams can be imagined

in which all members are working at different locations and communicate only via electronic

media, most of the existing virtual teams have some face-to-face contact. At the same time,

electronic communication media are not only used in virtual teams but also in conventional

teams. Instead of trying to draw a clear line between virtual and non-virtual teams, it might be

more fruitful to consider the relative virtuality of a team and its consequences for

management (Axtell et al., 2004; Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Griffith & Neale, 2001). From this

perspective, virtuality of a team is one aspect among other team characteristics (e.g.,

diversity, autonomy, time-restriction) that might broaden our understanding of teamwork in

general. Potential indicators or measures of virtuality are the relation of face-to-face to

nonface-to-face communication, the average distance between the members, or the number of

working sites represented in the team together with the number of members at each site

(Kirkman et al., 2004; O’Leary & Cummings, 2002). Similar to other human resource

policies, the consequences of implementing high virtuality in teams can be evaluated at the

individual, organizational, and societal level. At the individual level, potential advantages of

Distributed work across different locations and/or working times is not a phenomenon of the

last 15 years. There are many instructive examples of how people collaborated across larger

distances in earlier times (King & Frost, 2002; O’Leary, Orlikowski, & Yates, 2002).

However, with the rapid development of electronic information and communication media in

the last years, distributed work has become much easier, faster and more efficient. The first is

telework (telecommuting) which is done partially or completely outside of the main company

workplace with the aid of information and telecommunication services (Bailey & Kurland,

2002; Konradt, Schmook, & Ma¨lecke, 2000). Virtual groups exists when several teleworkers

are combined and each member reports to the same manager. In contrast, a virtual team exists

when the members of a virtual group interact with each other in order to accomplish common

goals (Lipnack & Stamps, 1997). This distinction between virtual group and virtual team is

parallel to the distinction between conventional groups and teams in the organizational

literature (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003). Finally, virtual communities are larger entities of

distributed work in which members participate via the Internet, guided by common purposes,

roles and norms. In contrast to virtual teams, virtual communities are not implemented within

an organizational structure but are usually initiated by some of their members. Examples of

virtual communities are Open Source software projects (Hertel, Niedner, & Herrmann, 2003;

Moon & Sproull, 2002) or scientific collaboratories (Finholt, 2002). For reasons of

feasibility, the current review is restricted to virtual teams. Apart from these more general

differentiations, the more specific definition of virtual teams is still controversial (Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Griffith & Neale, 2000; Maznevski & Chudoba, 2000). As a minimal

consensus, virtual teams consist of (a) two or more persons who (b) collaborate interactively

to achieve common goals, while (c) at least one of the team members works at a different

location, organization, or at a different time so that (d) communication and coordination is

predominantly based on electronic communication media (email, fax, phone, video

conference, etc.). It is important to note that the latter two aspects in this definition are

considered as dimensions rather than as dichotomized criteria that distinguish virtual teams

from conventional face-to-face teams. While extreme cases of virtual teams can be imagined

in which all members are working at different locations and communicate only via electronic

media, most of the existing virtual teams have some face-to-face contact. At the same time,

electronic communication media are not only used in virtual teams but also in conventional

teams. Instead of trying to draw a clear line between virtual and non-virtual teams, it might be

more fruitful to consider the relative virtuality of a team and its consequences for

management (Axtell et al., 2004; Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Griffith & Neale, 2001). From this

perspective, virtuality of a team is one aspect among other team characteristics (e.g.,

diversity, autonomy, time-restriction) that might broaden our understanding of teamwork in

general. Potential indicators or measures of virtuality are the relation of face-to-face to

nonface-to-face communication, the average distance between the members, or the number of

working sites represented in the team together with the number of members at each site

(Kirkman et al., 2004; O’Leary & Cummings, 2002). Similar to other human resource

policies, the consequences of implementing high virtuality in teams can be evaluated at the

individual, organizational, and societal level. At the individual level, potential advantages of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

high virtuality include higher flexibility and time control together with higher responsibilities,

work motivation, and empowerment of the team members. Challenges on the other hand are

feelings of isolation and decreased interpersonal contact, increased chances of

misunderstandings and conflict escalation, and increased opportunities of role ambiguity and

goal conflicts due to commitments to different work-units. At the organizational level, virtual

teams have particularly strategic advantages. For instance, teams can be staffed based on

members’ expertise instead of their local availability, teams can work around the clock by

having team members in different time zones, speed and flexibility in response to market

demands can be increased, a closer connection to suppliers and/or customers can be

accomplished, and expenses for traveling and office space can be reduced. Potential

challenges at this level include difficulties to supervise team members’ activities and to

prevent unproductive developments in time, along with additional costs for appropriate

technology, issues of data security, and additional training programs. Finally, at the societal

level, the implementation of virtual teams can help to develop regions with low infrastructure

and employment rate, to integrate persons with low mobility due to handicaps or family care

duties, and to decrease environmental strains by reducing commuting traffic and air pollution.

However, virtual teams can also increase the isolation between people due to a technical

work environment. These numerous advantages and challenges at all three evaluation levels

call for guidance in order to profit from the advantages and to minimize the potential

drawbacks.

Most research has focused on the advantages and disadvantages of virtual teams. Relative to

face-to-face teams, benefits attributed to the use of virtual teams include the ability to

compose a team of experts flung across space and time, increases in staffing flexibility to

meet market demands, and cost savings from reduced travel (Kirkman, Gibson, & Kim, 2012;

Kirkman & Malthieu, 2005; Stanko & Gibson, 2009). Disadvantages include lower levels of

team cohesion, work satisfaction, trust, cooperative behavior, social control, and commitment

to team goals; all factors that can negatively impact team performance. There is consensus

among scholars that virtual teams are more difficult to lead than face-to-face teams (Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Duarte & Snyder, 2001; Gibson & Cohen, 2003; Hinds & Kiesler, 2002;

Lipnack & Stamps, 2000). As a consequence of the lack of face-to-face contact and

geographical dispersion, as well as the (often) asynchronous nature of communication, it is

more difficult for team leaders to perform traditional hierarchical leadership behaviors such

as motivating members and managing team dynamics (Avolio et al., 2000; Bell & Kozlowski,

2002; Purvanova & Bono, 2009). It has been argued that leader influence can be extended by

having leadership augmented by new media (Avolio & Kahai, 2003; Avolio et al., 2000) and

that team leaders simply have to learn how to use and apply those media properly. Findings

from empirical research show that getting virtual teams to function equivalently to face-to-

face teams requires virtual team leaders to invest much more time and effort (Purvanova &

Bono, 2009), although showing more initiative, trying harder, and investing more time and

energy might not always be feasible. Some scholars suggest that leadership functions should

be supplemented by providing structural supports (Bell & Kozlowki, 2002; Hinds & Kiesler,

2002; Kahai, Sosik, & Avolio, 2003). For example, structuring rewards to provide incentives

for performance should result in higher motivation. Another suggested approach is to

work motivation, and empowerment of the team members. Challenges on the other hand are

feelings of isolation and decreased interpersonal contact, increased chances of

misunderstandings and conflict escalation, and increased opportunities of role ambiguity and

goal conflicts due to commitments to different work-units. At the organizational level, virtual

teams have particularly strategic advantages. For instance, teams can be staffed based on

members’ expertise instead of their local availability, teams can work around the clock by

having team members in different time zones, speed and flexibility in response to market

demands can be increased, a closer connection to suppliers and/or customers can be

accomplished, and expenses for traveling and office space can be reduced. Potential

challenges at this level include difficulties to supervise team members’ activities and to

prevent unproductive developments in time, along with additional costs for appropriate

technology, issues of data security, and additional training programs. Finally, at the societal

level, the implementation of virtual teams can help to develop regions with low infrastructure

and employment rate, to integrate persons with low mobility due to handicaps or family care

duties, and to decrease environmental strains by reducing commuting traffic and air pollution.

However, virtual teams can also increase the isolation between people due to a technical

work environment. These numerous advantages and challenges at all three evaluation levels

call for guidance in order to profit from the advantages and to minimize the potential

drawbacks.

Most research has focused on the advantages and disadvantages of virtual teams. Relative to

face-to-face teams, benefits attributed to the use of virtual teams include the ability to

compose a team of experts flung across space and time, increases in staffing flexibility to

meet market demands, and cost savings from reduced travel (Kirkman, Gibson, & Kim, 2012;

Kirkman & Malthieu, 2005; Stanko & Gibson, 2009). Disadvantages include lower levels of

team cohesion, work satisfaction, trust, cooperative behavior, social control, and commitment

to team goals; all factors that can negatively impact team performance. There is consensus

among scholars that virtual teams are more difficult to lead than face-to-face teams (Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Duarte & Snyder, 2001; Gibson & Cohen, 2003; Hinds & Kiesler, 2002;

Lipnack & Stamps, 2000). As a consequence of the lack of face-to-face contact and

geographical dispersion, as well as the (often) asynchronous nature of communication, it is

more difficult for team leaders to perform traditional hierarchical leadership behaviors such

as motivating members and managing team dynamics (Avolio et al., 2000; Bell & Kozlowski,

2002; Purvanova & Bono, 2009). It has been argued that leader influence can be extended by

having leadership augmented by new media (Avolio & Kahai, 2003; Avolio et al., 2000) and

that team leaders simply have to learn how to use and apply those media properly. Findings

from empirical research show that getting virtual teams to function equivalently to face-to-

face teams requires virtual team leaders to invest much more time and effort (Purvanova &

Bono, 2009), although showing more initiative, trying harder, and investing more time and

energy might not always be feasible. Some scholars suggest that leadership functions should

be supplemented by providing structural supports (Bell & Kozlowki, 2002; Hinds & Kiesler,

2002; Kahai, Sosik, & Avolio, 2003). For example, structuring rewards to provide incentives

for performance should result in higher motivation. Another suggested approach is to

supplement leadership by distributing leadership to team members (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002).

Sharing leadership with team members is based on the premise that leadership should not be

the sole responsibility of a hierarchical leader, but should be collectively exercised by

empowering and developing individual team members (Kirkman, Rosen, Tesluk, & Gibson,

2004). Although this view of leadership challenges in virtual teams has consensus in the

literature, it has not been subjected to empirical verification. With respect to improving team

performance, it is important to understand the extent to which the influence of hierarchical

leadership is attenuated (or not) as team virtuality increases. Moreover, if the influence of

hierarchical leadership is diminished as is suspected, then the extent to which it can be

supplemented by structural supports and shared team leadership (and, potentially, other

supplements) becomes a critical target for theory and research extensions. To examine these

issues, our conceptual model treats hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared

team leadership as inputs to team performance. The model is illustrated in Figure 1. The basic

premise of our approach is that supplementing hierarchical leadership with shared leadership

and structural supports will be more relevant when teams are more virtual in nature. Thus, the

degree of team virtuality is predicted to moderate the relationships between hierarchical

leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership with team performance. There are

two notable aspects of the model. First, it is focused on the contribution of these input factors

to team performance. The model does not focus on mediating processes at this stage of the

research. The primary reason for this focused approach is to enable a clear evaluation of the

moderating effects of virtuality on the contributions of hierarchical leadership, structural

supports, and shared leadership to team performance. Second, the inputs are conceptualized

as distinct higher-order factors or construct composites, rather than unitary constructs. This

allows each of the inputs to be conceptualized as a composite of established constructs. For

example, hierarchical leadership is represented by transformational leadership, leader–

member exchange, and supervisory mentoring. Each of these constructs, as core aspects of

hierarchical leadership, is supported by a body of theory and empirical research with

established measures. Using established constructs and measures of hierarchical leadership as

input factors allows us to clearly assess the potential supplementary influence provided by

structural supports and shared leadership. The same conceptual and measurement approach

using established constructs and measures is applied to structural supports and shared

leadership.

With the growth and evolution of virtual teams during the past decade, researchers have

focused on the conceptualization and measurement of team virtuality (e.g., Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Hinds, Liu, & Lyon, 2011; Kirkman & Malthieu, 2005). In early research,

virtuality was treated as distinctly categorical; researchers applied a simple dichotomous

characterization of virtual and face-to-face teams. More recently, however, scholars have

asserted that this simple characterization glosses over a variety of nuanced dimensions that

underlie a range of differences in the degree of virtuality (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006;

MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2011). Whereas early

conceptualizations focused exclusively on geographic distribution, subsequent

conceptualizations added electronic communication and noted differences between the use of

asynchronous and synchronous communications (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002). Empirical

Sharing leadership with team members is based on the premise that leadership should not be

the sole responsibility of a hierarchical leader, but should be collectively exercised by

empowering and developing individual team members (Kirkman, Rosen, Tesluk, & Gibson,

2004). Although this view of leadership challenges in virtual teams has consensus in the

literature, it has not been subjected to empirical verification. With respect to improving team

performance, it is important to understand the extent to which the influence of hierarchical

leadership is attenuated (or not) as team virtuality increases. Moreover, if the influence of

hierarchical leadership is diminished as is suspected, then the extent to which it can be

supplemented by structural supports and shared team leadership (and, potentially, other

supplements) becomes a critical target for theory and research extensions. To examine these

issues, our conceptual model treats hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared

team leadership as inputs to team performance. The model is illustrated in Figure 1. The basic

premise of our approach is that supplementing hierarchical leadership with shared leadership

and structural supports will be more relevant when teams are more virtual in nature. Thus, the

degree of team virtuality is predicted to moderate the relationships between hierarchical

leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership with team performance. There are

two notable aspects of the model. First, it is focused on the contribution of these input factors

to team performance. The model does not focus on mediating processes at this stage of the

research. The primary reason for this focused approach is to enable a clear evaluation of the

moderating effects of virtuality on the contributions of hierarchical leadership, structural

supports, and shared leadership to team performance. Second, the inputs are conceptualized

as distinct higher-order factors or construct composites, rather than unitary constructs. This

allows each of the inputs to be conceptualized as a composite of established constructs. For

example, hierarchical leadership is represented by transformational leadership, leader–

member exchange, and supervisory mentoring. Each of these constructs, as core aspects of

hierarchical leadership, is supported by a body of theory and empirical research with

established measures. Using established constructs and measures of hierarchical leadership as

input factors allows us to clearly assess the potential supplementary influence provided by

structural supports and shared leadership. The same conceptual and measurement approach

using established constructs and measures is applied to structural supports and shared

leadership.

With the growth and evolution of virtual teams during the past decade, researchers have

focused on the conceptualization and measurement of team virtuality (e.g., Bell &

Kozlowski, 2002; Hinds, Liu, & Lyon, 2011; Kirkman & Malthieu, 2005). In early research,

virtuality was treated as distinctly categorical; researchers applied a simple dichotomous

characterization of virtual and face-to-face teams. More recently, however, scholars have

asserted that this simple characterization glosses over a variety of nuanced dimensions that

underlie a range of differences in the degree of virtuality (Gibson & Gibbs, 2006;

MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2011). Whereas early

conceptualizations focused exclusively on geographic distribution, subsequent

conceptualizations added electronic communication and noted differences between the use of

asynchronous and synchronous communications (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002). Empirical

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

research, accordingly, refers to both the facets of geographic distribution (e.g., O’Leary &

Cummings, 2007; O’Leary & Mortensen, 2010) as well as the relative amount of e-

communication media usage (Griffith, Sawyer, & Neale, 2003; Kirkman et al., 2004;

MesmerMagnus et al., 2011) as indicative of “team virtuality.” This is now the established

approach to conceptualizing virtuality.

However, virtual teams increasingly span national boundaries and differences in cultural

background are becoming more important to consider as an aspect of virtuality (Hinds et al.,

2011; Staples & Zhao, 2006; Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, 2007). Indeed, Hinds et al. (2011)

criticized the lack of inclusion of national and cultural differences in conceptualizations of

virtuality. As “organizations are increasingly compelled to establish a presence in multiple

countries as a means of reducing labor costs, capturing specialized expertise, and

understanding emerging markets... they often create conditions in which workers must

collaborate across national boundaries” (Hinds et al., 2011, p. 136). Accordingly, researchers

need to put the global back into “global work” by considering cultural differences. Research

is increasingly considering cultural differences as an important component of virtuality in

globally dispersed teams (Chen, Kirkman, Kim, Farh, & Tangirala, 2010; Gibson & Gibbs,

2006; Tsui et al., 2007). Based on this evolving view of virtuality, our conceptualization

comprises geographic distribution (e.g., O’Leary & Cummings, 2007), relative amount of e-

communication media usage (e.g., Kirkman et al., 2004), and cultural diversity (e.g., Gibson

& Gibbs, 2006; Hinds et al., 2011; Tsui et al., 2007) as an addition to the established

components of team virtuality.

In virtual teams, the stability and reduction of ambiguity provided by structural supports may

compensate for the turbulence and unpredictability that characterizes virtual teamwork

(Zaccaro & Bader, 2003; Zigurs, 2003). Bell and Kozlowski (2002) argued that because of

the geographic dispersion of virtual teams, an important function of leadership is to create

structures and routines that substitute for direct leadership influence and regulate team

behavior. Consistent with research that suggests structural supports have direct relationships

with outcomes that supplement hierarchical leadership (Podsakoff et al., 1996), our model

conceptualizes them as having a direct relationship rather than a moderating one. Virtual

team members usually work on virtual teams in addition to their line function and research

has highlighted the importance of rewarding virtual team members for both aspects.

Geographical dispersion can result in a lack of motivation to focus on virtual team

responsibilities, makes monitoring of virtual team members difficult, and also creates higher

levels of anonymity (Wiesenfeld, Raghuram, & Garud, 1999). Further, reward systems need

to be fair, such that individual employees perceive they are being rewarded according to their

inputs (e.g., effort, time, performance, etc.) on their virtual team work (Colquitt, 2004;

Dulebohn & Martocchio, 1998; Schminke, Cropanzano, & Rupp, 2002). Being rewarded in a

fair and transparent way for the work performed on the virtual team will lead employees to

put more efforts toward virtual teamwork. Second, a major component of structural supports

is the communication and information management systems used for virtual teams. Building

and managing communication and information management systems that facilitate

connectivity, remove perceptions of distance, and facilitate the organization and accessibility

Cummings, 2007; O’Leary & Mortensen, 2010) as well as the relative amount of e-

communication media usage (Griffith, Sawyer, & Neale, 2003; Kirkman et al., 2004;

MesmerMagnus et al., 2011) as indicative of “team virtuality.” This is now the established

approach to conceptualizing virtuality.

However, virtual teams increasingly span national boundaries and differences in cultural

background are becoming more important to consider as an aspect of virtuality (Hinds et al.,

2011; Staples & Zhao, 2006; Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, 2007). Indeed, Hinds et al. (2011)

criticized the lack of inclusion of national and cultural differences in conceptualizations of

virtuality. As “organizations are increasingly compelled to establish a presence in multiple

countries as a means of reducing labor costs, capturing specialized expertise, and

understanding emerging markets... they often create conditions in which workers must

collaborate across national boundaries” (Hinds et al., 2011, p. 136). Accordingly, researchers

need to put the global back into “global work” by considering cultural differences. Research

is increasingly considering cultural differences as an important component of virtuality in

globally dispersed teams (Chen, Kirkman, Kim, Farh, & Tangirala, 2010; Gibson & Gibbs,

2006; Tsui et al., 2007). Based on this evolving view of virtuality, our conceptualization

comprises geographic distribution (e.g., O’Leary & Cummings, 2007), relative amount of e-

communication media usage (e.g., Kirkman et al., 2004), and cultural diversity (e.g., Gibson

& Gibbs, 2006; Hinds et al., 2011; Tsui et al., 2007) as an addition to the established

components of team virtuality.

In virtual teams, the stability and reduction of ambiguity provided by structural supports may

compensate for the turbulence and unpredictability that characterizes virtual teamwork

(Zaccaro & Bader, 2003; Zigurs, 2003). Bell and Kozlowski (2002) argued that because of

the geographic dispersion of virtual teams, an important function of leadership is to create

structures and routines that substitute for direct leadership influence and regulate team

behavior. Consistent with research that suggests structural supports have direct relationships

with outcomes that supplement hierarchical leadership (Podsakoff et al., 1996), our model

conceptualizes them as having a direct relationship rather than a moderating one. Virtual

team members usually work on virtual teams in addition to their line function and research

has highlighted the importance of rewarding virtual team members for both aspects.

Geographical dispersion can result in a lack of motivation to focus on virtual team

responsibilities, makes monitoring of virtual team members difficult, and also creates higher

levels of anonymity (Wiesenfeld, Raghuram, & Garud, 1999). Further, reward systems need

to be fair, such that individual employees perceive they are being rewarded according to their

inputs (e.g., effort, time, performance, etc.) on their virtual team work (Colquitt, 2004;

Dulebohn & Martocchio, 1998; Schminke, Cropanzano, & Rupp, 2002). Being rewarded in a

fair and transparent way for the work performed on the virtual team will lead employees to

put more efforts toward virtual teamwork. Second, a major component of structural supports

is the communication and information management systems used for virtual teams. Building

and managing communication and information management systems that facilitate

connectivity, remove perceptions of distance, and facilitate the organization and accessibility

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

of information can reduce feelings of lack of trust, anonymity, deindividuation, and

perceptions of low social control. In addition, virtual teamwork is typically white-collar,

knowledge based, intellectual, and interdependent. The management of communication and

information is central to cognitive tasks (Clampitt & Downs, 2004; Faraj & Sproull, 2000).

Thus, a key aspect of performance in virtual teams is managing the “triangle” of factors:

shared knowledge (in changing and flexible organization structure), via electronic

communication systems, and with experts as primary collaborators (Griffith et al., 2003;

Kanawattanachai & Yoo, 2007; Malhotra & Majchrzak, 2004). As a form of structural

support, managing communication and information flow (Fleishman et al., 1991) include

information infrastructure and quality of information received, as well as the transparency

and adequacy of communication and information management. Communication and

information management are posited to influence virtual team performance. We expect that

team virtuality moderates the relationship between structural supports and team performance.

Shared team leadership describes a mutual influence process, characterized by collaborative

decision-making and shared responsibility, whereby team members lead each other toward

the achievement of goals (Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2004; Pearce & Conger, 2003). Shared team

leadership is presumed to create stronger bonds among the team members; facilitate trust,

cohesion, and commitment; and mitigate disadvantages of virtual teams (Pearce & Conger,

2003). Thus, sharing leadership functions with team members provides a mechanism to

supplement hierarchical leadership in virtual teams (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Pearce, Yoo, &

Alavi, 2004; Tyran, Tyran, & Shepherd, 2003). Scholars have argued that shared leadership is

a more appropriate form of team leadership than hierarchical leadership represented by the

solo leader (Brown & Gioia, 2002; Day et al., 2004; Yukl, 2010). Reasons for this include the

notion that team member communication is less formal and less hierarchically based, and,

therefore, team members can more easily overcome communication difficulties (Bell &

Kozlowki, 2002; Pearce et al., 2004). In addition, work processes in virtual teams are

characterized as cognitively loaded, highly interdependent, yet autonomous. Complex

teamwork requires the use of self-managing teams (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Pearce, 2004;

Pearce & Manz, 2005). Team self-management and empowerment, in this context, has been

shown to enhance virtual team performance in a sample 35 sales and service virtual teams in

a high-technology organization (Kirkman et al., 2004). There is no “one best way” to

measure shared leadership. The concept is in its infancy (Avolio, Jung, Murry, &

Sivasbramaniam, 1996; Carson, Tesluk, & Marrone, 2007; Mayo, Meindl, & Pastor, 2003;

Mehra, Smith, Dixon, & Robertson, 2006; Pearce & Conger, 2003), and, thus, a challenge

facing researchers is determining how to measure shared team leadership. One primary

approach has simply treated shared team leadership as analogous to hierarchical leadership,

but conceptualized at the team level of analysis (Pearce & Sims, 2002). This approach

assesses shared leadership as collective concept in the form of traditional leadership

behaviors (e.g., transformational leadership) that are performed by team members. Typically,

a traditional leadership measure—like transformational leadership—is referenced to the team

as a collective to comprise shared team leadership. However, consistent with other

researchers (Carson et al., 2007; Mayo et al., 2003; Mehra et al., 2006), we do not

conceptualize shared team leadership as parallel with hierarchical leadership. Team members

perceptions of low social control. In addition, virtual teamwork is typically white-collar,

knowledge based, intellectual, and interdependent. The management of communication and

information is central to cognitive tasks (Clampitt & Downs, 2004; Faraj & Sproull, 2000).

Thus, a key aspect of performance in virtual teams is managing the “triangle” of factors:

shared knowledge (in changing and flexible organization structure), via electronic

communication systems, and with experts as primary collaborators (Griffith et al., 2003;

Kanawattanachai & Yoo, 2007; Malhotra & Majchrzak, 2004). As a form of structural

support, managing communication and information flow (Fleishman et al., 1991) include

information infrastructure and quality of information received, as well as the transparency

and adequacy of communication and information management. Communication and

information management are posited to influence virtual team performance. We expect that

team virtuality moderates the relationship between structural supports and team performance.

Shared team leadership describes a mutual influence process, characterized by collaborative

decision-making and shared responsibility, whereby team members lead each other toward

the achievement of goals (Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2004; Pearce & Conger, 2003). Shared team

leadership is presumed to create stronger bonds among the team members; facilitate trust,

cohesion, and commitment; and mitigate disadvantages of virtual teams (Pearce & Conger,

2003). Thus, sharing leadership functions with team members provides a mechanism to

supplement hierarchical leadership in virtual teams (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Pearce, Yoo, &

Alavi, 2004; Tyran, Tyran, & Shepherd, 2003). Scholars have argued that shared leadership is

a more appropriate form of team leadership than hierarchical leadership represented by the

solo leader (Brown & Gioia, 2002; Day et al., 2004; Yukl, 2010). Reasons for this include the

notion that team member communication is less formal and less hierarchically based, and,

therefore, team members can more easily overcome communication difficulties (Bell &

Kozlowki, 2002; Pearce et al., 2004). In addition, work processes in virtual teams are

characterized as cognitively loaded, highly interdependent, yet autonomous. Complex

teamwork requires the use of self-managing teams (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Pearce, 2004;

Pearce & Manz, 2005). Team self-management and empowerment, in this context, has been

shown to enhance virtual team performance in a sample 35 sales and service virtual teams in

a high-technology organization (Kirkman et al., 2004). There is no “one best way” to

measure shared leadership. The concept is in its infancy (Avolio, Jung, Murry, &

Sivasbramaniam, 1996; Carson, Tesluk, & Marrone, 2007; Mayo, Meindl, & Pastor, 2003;

Mehra, Smith, Dixon, & Robertson, 2006; Pearce & Conger, 2003), and, thus, a challenge

facing researchers is determining how to measure shared team leadership. One primary

approach has simply treated shared team leadership as analogous to hierarchical leadership,

but conceptualized at the team level of analysis (Pearce & Sims, 2002). This approach

assesses shared leadership as collective concept in the form of traditional leadership

behaviors (e.g., transformational leadership) that are performed by team members. Typically,

a traditional leadership measure—like transformational leadership—is referenced to the team

as a collective to comprise shared team leadership. However, consistent with other

researchers (Carson et al., 2007; Mayo et al., 2003; Mehra et al., 2006), we do not

conceptualize shared team leadership as parallel with hierarchical leadership. Team members

do not need to necessarily perform the same kind of leadership behaviors as their supervisors

(Künzle et al., 2010; Morgeson et al., 2010) in order to engage in shared leadership. Rather,

shared leadership can be conceptualized as the extent to which team members behave in ways

to prompt the team processes that underlie team performance. Team process researchers have

distinguished cognitive, affective-motivational, and behavioral functions as keys to team

effectiveness (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006). Team leader

effectiveness, as outlined in functional leadership (McGrath, 1962), is based on leaders

addressing the cognitive, affective, and behavioral functioning of their teams (Zaccaro,

Rittman, & Marks, 2001). These leadership functions can be performed through informal

leadership mechanisms (Morgeson et al., 2010) such as shared team leadership. In capturing

shared leadership in virtual teams, affectivemotivational functions can be represented in

terms of perceived team support, which is related to building trust and team cohesion

(Kasper-Fuehrer & Ashkanasy, 2001) and may compensate for specific gaps resulting from

the lack of face-to-face meetings in virtual teams, that is, lack of trust, and higher levels of

anonymity (Jarvenpaa, 2004; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999).

In the industrial economy organizations were typically structured hierarchically and,

consequently, information was filtered through hierarchical structures and formal authority

(Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003), whereas in the new networked economy, power and

information are hyperlinked and informal (Pulley, McCarthy, and Taylor, 2000). Inside

organizations, there has been a movement from hierarchies towards flat, web-like

organizations that enable better knowledge flows among business and allow spanning of

organizational boundaries (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003). The boundaries have become

blurred (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi 2003), which facilitates relationship-building inside

organizations mainly through strong ties, and between different organizations through weak

ties (Granowetter, 1973). Organizations no longer operate as stand-alone entities, but create

networks of customers, suppliers, and partners (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003) enabled by

information and communication technologies. At a broader level, economic development,

such as the deregulation of many product and service industries, have led to reformulations in

organizations (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). The growing popularity of inter organizational

alliances, and a shift from production to service-related business (Kayworth & Leidner,

2002), have changed the ways to organize and manage work. Such changes have mainly been

facilitated by information and communication technologies that improve knowledge

management (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003) and dissemination of information on the global

level, and have created new working methods and organizational structures increasing

flexibility (Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998), enhancing more effective

goalreaching and enabling organizational success in global setting. In consequence, the

exponential explosion in communication technologies has resulted in greater frequency of

daily interactions with different actors (Zaccaro & Bader, 2003) who may be dispersed in

different units of the same organization, in diversified geographic locations nationally or

internationally, and in different time zones throughout the world. As a result, organizational

work as well as leadership have become increasingly global (Zaccaro & Bader, 2003) due to

spanned organizational boundaries (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003), and web-like working

environments based on the use of information and communication technology. Companies

(Künzle et al., 2010; Morgeson et al., 2010) in order to engage in shared leadership. Rather,

shared leadership can be conceptualized as the extent to which team members behave in ways

to prompt the team processes that underlie team performance. Team process researchers have

distinguished cognitive, affective-motivational, and behavioral functions as keys to team

effectiveness (Kozlowski & Bell, 2003; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006). Team leader

effectiveness, as outlined in functional leadership (McGrath, 1962), is based on leaders

addressing the cognitive, affective, and behavioral functioning of their teams (Zaccaro,

Rittman, & Marks, 2001). These leadership functions can be performed through informal

leadership mechanisms (Morgeson et al., 2010) such as shared team leadership. In capturing

shared leadership in virtual teams, affectivemotivational functions can be represented in

terms of perceived team support, which is related to building trust and team cohesion

(Kasper-Fuehrer & Ashkanasy, 2001) and may compensate for specific gaps resulting from

the lack of face-to-face meetings in virtual teams, that is, lack of trust, and higher levels of

anonymity (Jarvenpaa, 2004; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999).

In the industrial economy organizations were typically structured hierarchically and,

consequently, information was filtered through hierarchical structures and formal authority

(Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003), whereas in the new networked economy, power and

information are hyperlinked and informal (Pulley, McCarthy, and Taylor, 2000). Inside

organizations, there has been a movement from hierarchies towards flat, web-like

organizations that enable better knowledge flows among business and allow spanning of

organizational boundaries (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003). The boundaries have become

blurred (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi 2003), which facilitates relationship-building inside

organizations mainly through strong ties, and between different organizations through weak

ties (Granowetter, 1973). Organizations no longer operate as stand-alone entities, but create

networks of customers, suppliers, and partners (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003) enabled by

information and communication technologies. At a broader level, economic development,

such as the deregulation of many product and service industries, have led to reformulations in

organizations (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). The growing popularity of inter organizational

alliances, and a shift from production to service-related business (Kayworth & Leidner,

2002), have changed the ways to organize and manage work. Such changes have mainly been

facilitated by information and communication technologies that improve knowledge

management (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003) and dissemination of information on the global

level, and have created new working methods and organizational structures increasing

flexibility (Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998), enhancing more effective

goalreaching and enabling organizational success in global setting. In consequence, the

exponential explosion in communication technologies has resulted in greater frequency of

daily interactions with different actors (Zaccaro & Bader, 2003) who may be dispersed in

different units of the same organization, in diversified geographic locations nationally or

internationally, and in different time zones throughout the world. As a result, organizational

work as well as leadership have become increasingly global (Zaccaro & Bader, 2003) due to

spanned organizational boundaries (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003), and web-like working

environments based on the use of information and communication technology. Companies

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

have set up new arrangements that allow work to be done via cyberspace with increasing

levels of virtuality (Brunelle, 2012). As information and knowledge is diffused by modern

technology, working and innovation are shifting form structures inside the organization to

broader virtual knowledge networks that may reach across time and space boundaries making

physical location, buildings, and distribution channels less important (Jarvempaa &

Tanriverdi, 2003). Such less hierarchical organizations with blurred boundaries and more

flexible working arrangements, have greatly affected leadership posing leaders unique

challenges (Gallenkamp, Korsgaard, Assmann, Welpe, & Picot, 2011), which make them

obtain new skills, and display specific traits, attitudes and behaviors (Eissa, Webster, & Kim,

2012) while striving for organizational success. Accordingly, the new challenges, arising

mainly from the organizational and work-related changes, imply new ways to organize work

between globally dispersed experts, stakeholders, organizational units, and different

companies. One of new ways to organize work is the virtual team (Lipnack & Stamps, 1997;

Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998), or e-team team (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003).

Typically, virtual teams function independently of organizational boundaries, geographical

locations, and time zones while striving effectively to reach the team-specific goals. The

globally dispersed virtual team members are primarily linked through advanced information

and communications technology which helps them to provide diversified solutions to current

downsized and lean organizations (Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998). As a whole,

in organizational environments, throughout the world there has been an increasing reliance on

communication that takes place via electronic means (e.g., email, discussion boards, and

satellite conferencing) rather than traditional face-to-face communication (Olson-Buchanan,

Rechner, Sanchez, & Schmidtke, 2007). Such development is interpreted as a paradigm shift

in organization and leadership (Purvanova & Bono, 2009). Technological changes have made

it possible to manage work globally through virtual teams that enable working 24/7 as the

members may be dispersed globally throughout different time zones (Trivedi & Desai, 2012).

Virtual teams can make use of the best talents because work, knowledge generation,

management, and innovation are no longer locally or geographically bound, and moreover,

virtual teams allow flexibility as they are based on flat organizational structures without

hierarchies and central authority (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003). Team members can easily

participate in different projects since some members may be experts in several teams and,

consequently, hybrid forms of virtual teams, one overlaying the other, are no exceptions

(Gassmann & von Zedtwitz, 2003). Consequently, virtual teams can more easily respond to

the changing requirements of the environment by making use of the latest knowledge, and

adaptable working arrangements, and by taking advantage of increased application of

information and communication technologies. Research indicates that leaders make a critical

difference in team performance, and it seems that such findings are also applicable to virtual

teams (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). Even though the new paradigm of work – anytime,

anywhere, in real space or in cyberspace, in which employees operate remotely form each

other and form managers (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003) – appears already to be general

knowledge, and even though research on traditional leadership and team management is wide

and well documented, research on the influence of information and communication

technology on leadership in virtual teams is relatively young (Purvanova & Bono, 2009). In

consequence, there seem to be knowledge gaps regarding the challenges that the application

levels of virtuality (Brunelle, 2012). As information and knowledge is diffused by modern

technology, working and innovation are shifting form structures inside the organization to

broader virtual knowledge networks that may reach across time and space boundaries making

physical location, buildings, and distribution channels less important (Jarvempaa &

Tanriverdi, 2003). Such less hierarchical organizations with blurred boundaries and more

flexible working arrangements, have greatly affected leadership posing leaders unique

challenges (Gallenkamp, Korsgaard, Assmann, Welpe, & Picot, 2011), which make them

obtain new skills, and display specific traits, attitudes and behaviors (Eissa, Webster, & Kim,

2012) while striving for organizational success. Accordingly, the new challenges, arising

mainly from the organizational and work-related changes, imply new ways to organize work

between globally dispersed experts, stakeholders, organizational units, and different

companies. One of new ways to organize work is the virtual team (Lipnack & Stamps, 1997;

Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998), or e-team team (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003).

Typically, virtual teams function independently of organizational boundaries, geographical

locations, and time zones while striving effectively to reach the team-specific goals. The

globally dispersed virtual team members are primarily linked through advanced information

and communications technology which helps them to provide diversified solutions to current

downsized and lean organizations (Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998). As a whole,

in organizational environments, throughout the world there has been an increasing reliance on

communication that takes place via electronic means (e.g., email, discussion boards, and

satellite conferencing) rather than traditional face-to-face communication (Olson-Buchanan,

Rechner, Sanchez, & Schmidtke, 2007). Such development is interpreted as a paradigm shift

in organization and leadership (Purvanova & Bono, 2009). Technological changes have made

it possible to manage work globally through virtual teams that enable working 24/7 as the

members may be dispersed globally throughout different time zones (Trivedi & Desai, 2012).

Virtual teams can make use of the best talents because work, knowledge generation,

management, and innovation are no longer locally or geographically bound, and moreover,

virtual teams allow flexibility as they are based on flat organizational structures without

hierarchies and central authority (Jarvempaa & Tanriverdi, 2003). Team members can easily

participate in different projects since some members may be experts in several teams and,

consequently, hybrid forms of virtual teams, one overlaying the other, are no exceptions

(Gassmann & von Zedtwitz, 2003). Consequently, virtual teams can more easily respond to

the changing requirements of the environment by making use of the latest knowledge, and

adaptable working arrangements, and by taking advantage of increased application of

information and communication technologies. Research indicates that leaders make a critical

difference in team performance, and it seems that such findings are also applicable to virtual

teams (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003). Even though the new paradigm of work – anytime,

anywhere, in real space or in cyberspace, in which employees operate remotely form each

other and form managers (Cascio & Shurygailo, 2003) – appears already to be general

knowledge, and even though research on traditional leadership and team management is wide

and well documented, research on the influence of information and communication

technology on leadership in virtual teams is relatively young (Purvanova & Bono, 2009). In

consequence, there seem to be knowledge gaps regarding the challenges that the application

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

of communication and information technologies may imply for leadership. It is also asserted

that even though virtual project teams are on the rise in organizations (Purvanova & Bono,

2009) and becoming ubiquitous (Nunamaker, Reinig, & Brigg, 2009), studying an

organization that operates in a virtual context will be incomplete without knowledge of how

its leaders behave and interact with team members in order to guarantee an organization’s

success (Eissa, Fox, Webster, &Kim, 2012). Hence, there is growing need to add knowledge

about how increased application of information and communication technologies impacts

leaders’ behavior and performance in globally dispersed integrated organizations. In addition,

as the prevalent research on leadership is mainly based on leadership practiced on traditional

organizational settings (Kayworth & Leidner, 2002), based on physical contact between

organizational actors, the results may not applicable to leadership practiced in virtual teams.

As a whole, then, the emergence of new technological solutions, such as the Internet and the

World Wide Web as a powerful and highly transparent communication standard (Gassmann

& von Zedtwitz, 2003) facilitating global access to knowledge and its dispersion (Jarvempaa

& Tanriverdi, 2003), and new working arrangements, generate need for further research on

virtual environment in general, and leadership in such environment in particular. The new

technologically mediated working arrangements require new leadership approaches that may

explain how leadership is best practiced in virtual environment and what kind of leaders

make virtual teams succeed. It is argued that virtual teams are more difficult to manage than

traditional face-toface teams (Nunamaker, Reinig, & Brigg, 2009). Hence, the increasing

reliance on communication via electronic means in organizational settings throughout the

world (Olson-Buchanan, Rechner, Sanchez, & Schmidtke, 2007), and new pressures on

organizations to use global virtual teams (Montoya-Weiss, Massey, and Song, 2001) motivate

further research on virtual teams in general, and on leadership in virtual setting in particular.

Today, as many organizations are caught somewhere between old organizational structures

form the industrial age and new web-like structures created by information technologies and

indicating a transition towards virtual organizational environment, traditional assumptions

about leadership and organizations must evolve (Pulley & Sessa, 2001).

Research Methodology

The aim of the methodology in this part is to answer research questions. Firstly, to select the

most suitable research design among several ways, research questions and objectives will

have clearly explanation. After that, theoretical acknowledgment, in methodological process,

will be drawn out to support research design typologies, sampling, and ethics. Furthermore,

this research will use the questionnaire as the strategy. Also the final part will show

reliability, validity and ethics of questionnaires which decide the quality of research result.

Research Objectives and Research Question

There is no absolute definition of research. Through comparing of different definitions, Collis

& Hussey (2014, p.2) find similar points in description of business research which are “a

that even though virtual project teams are on the rise in organizations (Purvanova & Bono,

2009) and becoming ubiquitous (Nunamaker, Reinig, & Brigg, 2009), studying an

organization that operates in a virtual context will be incomplete without knowledge of how

its leaders behave and interact with team members in order to guarantee an organization’s

success (Eissa, Fox, Webster, &Kim, 2012). Hence, there is growing need to add knowledge

about how increased application of information and communication technologies impacts

leaders’ behavior and performance in globally dispersed integrated organizations. In addition,

as the prevalent research on leadership is mainly based on leadership practiced on traditional

organizational settings (Kayworth & Leidner, 2002), based on physical contact between

organizational actors, the results may not applicable to leadership practiced in virtual teams.

As a whole, then, the emergence of new technological solutions, such as the Internet and the

World Wide Web as a powerful and highly transparent communication standard (Gassmann

& von Zedtwitz, 2003) facilitating global access to knowledge and its dispersion (Jarvempaa

& Tanriverdi, 2003), and new working arrangements, generate need for further research on

virtual environment in general, and leadership in such environment in particular. The new

technologically mediated working arrangements require new leadership approaches that may

explain how leadership is best practiced in virtual environment and what kind of leaders

make virtual teams succeed. It is argued that virtual teams are more difficult to manage than

traditional face-toface teams (Nunamaker, Reinig, & Brigg, 2009). Hence, the increasing

reliance on communication via electronic means in organizational settings throughout the

world (Olson-Buchanan, Rechner, Sanchez, & Schmidtke, 2007), and new pressures on

organizations to use global virtual teams (Montoya-Weiss, Massey, and Song, 2001) motivate

further research on virtual teams in general, and on leadership in virtual setting in particular.

Today, as many organizations are caught somewhere between old organizational structures

form the industrial age and new web-like structures created by information technologies and

indicating a transition towards virtual organizational environment, traditional assumptions

about leadership and organizations must evolve (Pulley & Sessa, 2001).

Research Methodology

The aim of the methodology in this part is to answer research questions. Firstly, to select the

most suitable research design among several ways, research questions and objectives will

have clearly explanation. After that, theoretical acknowledgment, in methodological process,

will be drawn out to support research design typologies, sampling, and ethics. Furthermore,

this research will use the questionnaire as the strategy. Also the final part will show

reliability, validity and ethics of questionnaires which decide the quality of research result.

Research Objectives and Research Question

There is no absolute definition of research. Through comparing of different definitions, Collis

& Hussey (2014, p.2) find similar points in description of business research which are “a

process of inquiry and investigation, systematic and methodical, and increases knowledge”.

This finding shows that it is necessary for researchers to apply suitable methods in collecting

and analysing data process. The academic research is universal used to investigate some

specific questions to create some new knowledge based on the old one. These questions are

the central part of the whole research. Research objectives are used to show the direction and

main aim to realize the goal of research, which help to find the answer of the question that

has been ignored in the past (Churchill and Lacobucci, 2009). Research projects will be

measureable, detailed and clear by providing research objectives that in order to effective the

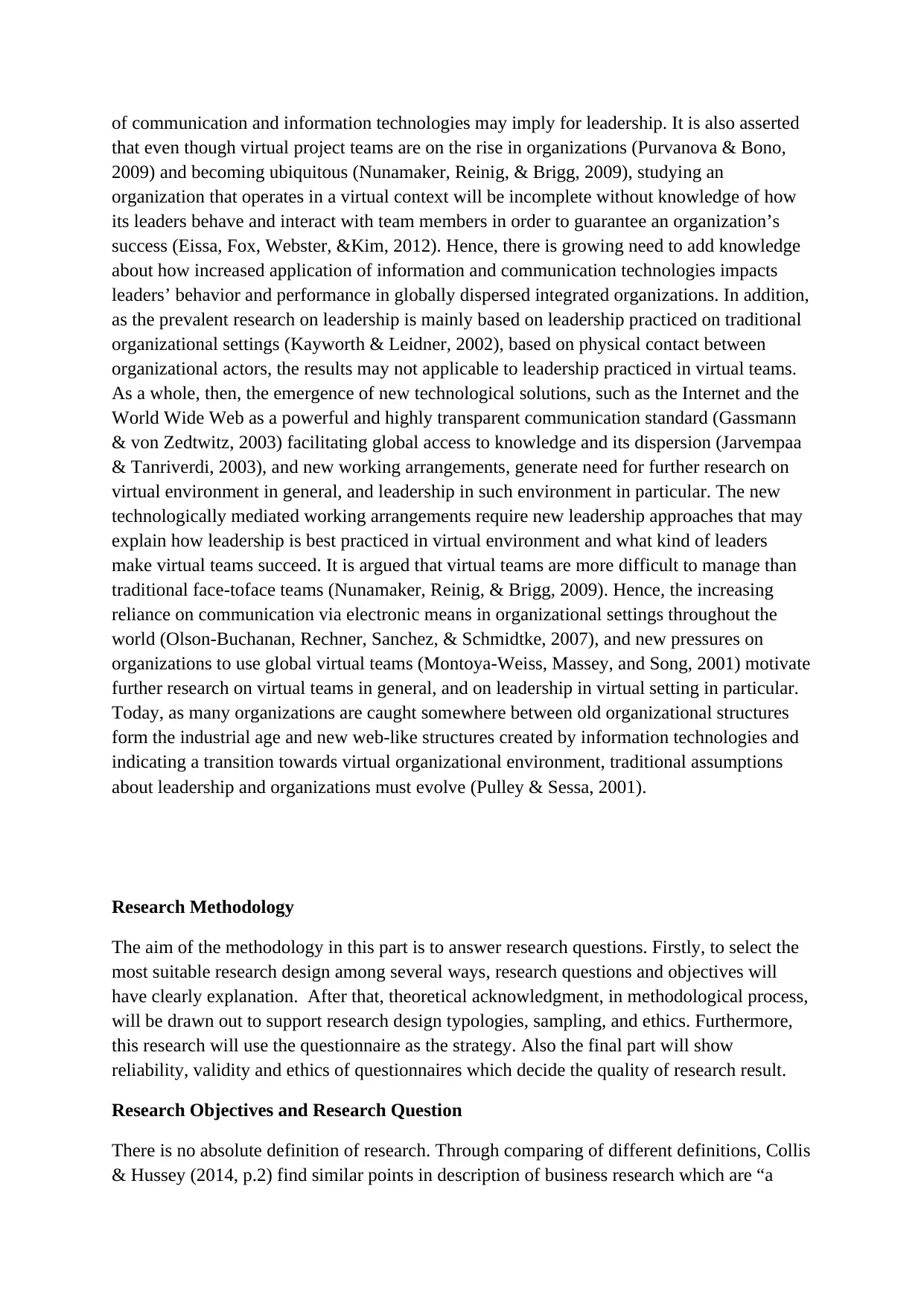

research process (Churchill and Lacobucci, 2009). The research objectives are grouped as

following through different research studies (Table 3.1):

Table 3.1: Research Objectives

Adapt From: Kothari (2004) Research Objectives

This project could be considered as exploratory research that aimed to conduct for a problem

that has not been clearly defined in the Higher education and brand equity area. The details of

research objectives for this projective refers to introduction in section .

Exploratory research design does not aim to provide the final and conclusive answers to the

research questions, but merely explores the research topic with varying levels of depth.

“Exploratory research tends to tackle new problems on which little or no previous research

has been done” (Brown, 2006, p.43). Moreover, it has to be noted that “exploratory research

is the initial research, which forms the basis of more conclusive research. It can even help in

determining the research design, sampling methodology and data collection method” (Singh,

2007, p.64).

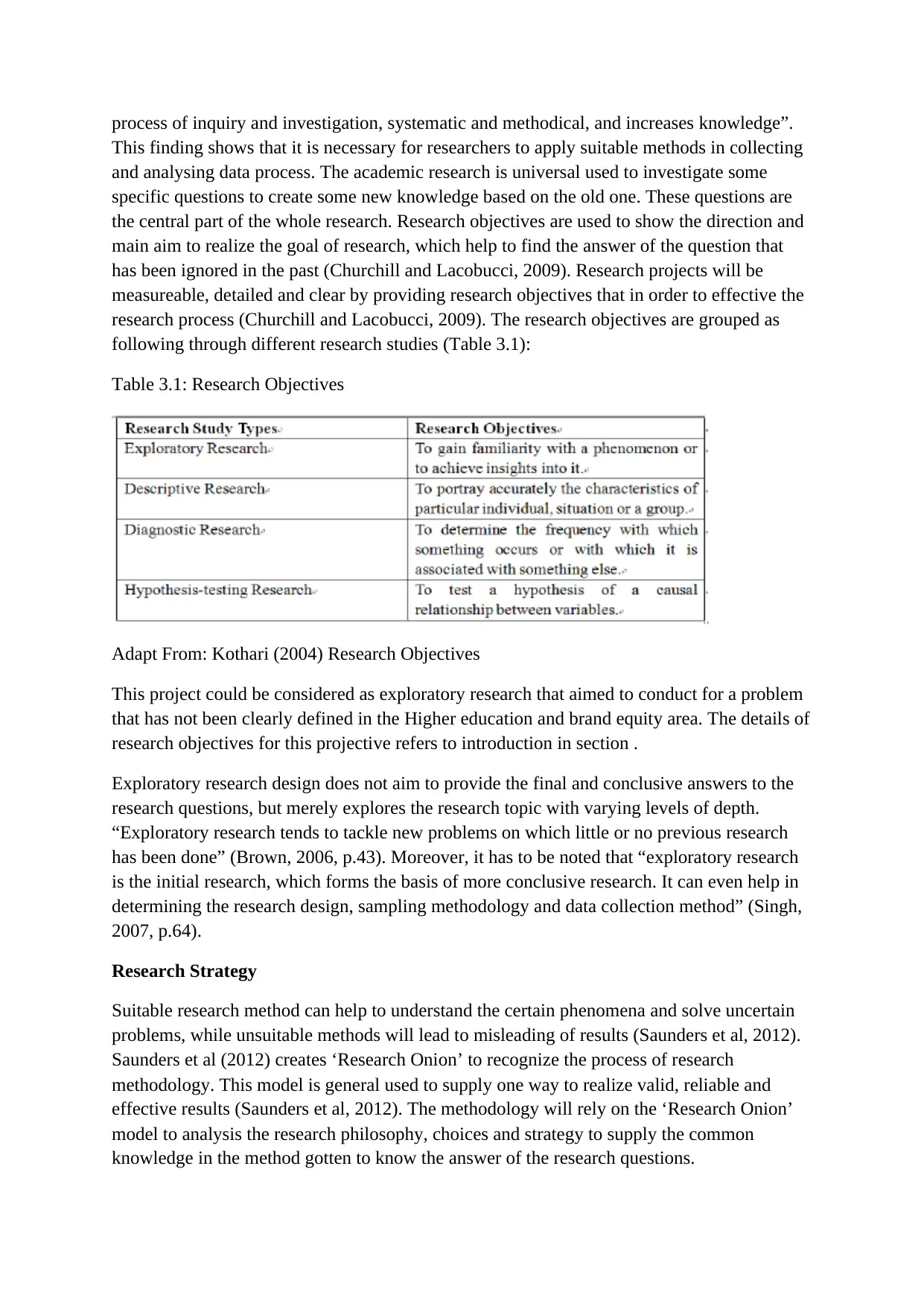

Research Strategy

Suitable research method can help to understand the certain phenomena and solve uncertain

problems, while unsuitable methods will lead to misleading of results (Saunders et al, 2012).

Saunders et al (2012) creates ‘Research Onion’ to recognize the process of research

methodology. This model is general used to supply one way to realize valid, reliable and

effective results (Saunders et al, 2012). The methodology will rely on the ‘Research Onion’

model to analysis the research philosophy, choices and strategy to supply the common

knowledge in the method gotten to know the answer of the research questions.

This finding shows that it is necessary for researchers to apply suitable methods in collecting

and analysing data process. The academic research is universal used to investigate some

specific questions to create some new knowledge based on the old one. These questions are

the central part of the whole research. Research objectives are used to show the direction and

main aim to realize the goal of research, which help to find the answer of the question that

has been ignored in the past (Churchill and Lacobucci, 2009). Research projects will be

measureable, detailed and clear by providing research objectives that in order to effective the

research process (Churchill and Lacobucci, 2009). The research objectives are grouped as

following through different research studies (Table 3.1):

Table 3.1: Research Objectives

Adapt From: Kothari (2004) Research Objectives

This project could be considered as exploratory research that aimed to conduct for a problem

that has not been clearly defined in the Higher education and brand equity area. The details of

research objectives for this projective refers to introduction in section .

Exploratory research design does not aim to provide the final and conclusive answers to the

research questions, but merely explores the research topic with varying levels of depth.

“Exploratory research tends to tackle new problems on which little or no previous research

has been done” (Brown, 2006, p.43). Moreover, it has to be noted that “exploratory research

is the initial research, which forms the basis of more conclusive research. It can even help in

determining the research design, sampling methodology and data collection method” (Singh,

2007, p.64).

Research Strategy

Suitable research method can help to understand the certain phenomena and solve uncertain

problems, while unsuitable methods will lead to misleading of results (Saunders et al, 2012).

Saunders et al (2012) creates ‘Research Onion’ to recognize the process of research

methodology. This model is general used to supply one way to realize valid, reliable and

effective results (Saunders et al, 2012). The methodology will rely on the ‘Research Onion’

model to analysis the research philosophy, choices and strategy to supply the common

knowledge in the method gotten to know the answer of the research questions.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Figure 3.1 Research Onion

Adapt from: Saunders et al (2012) Research Onion

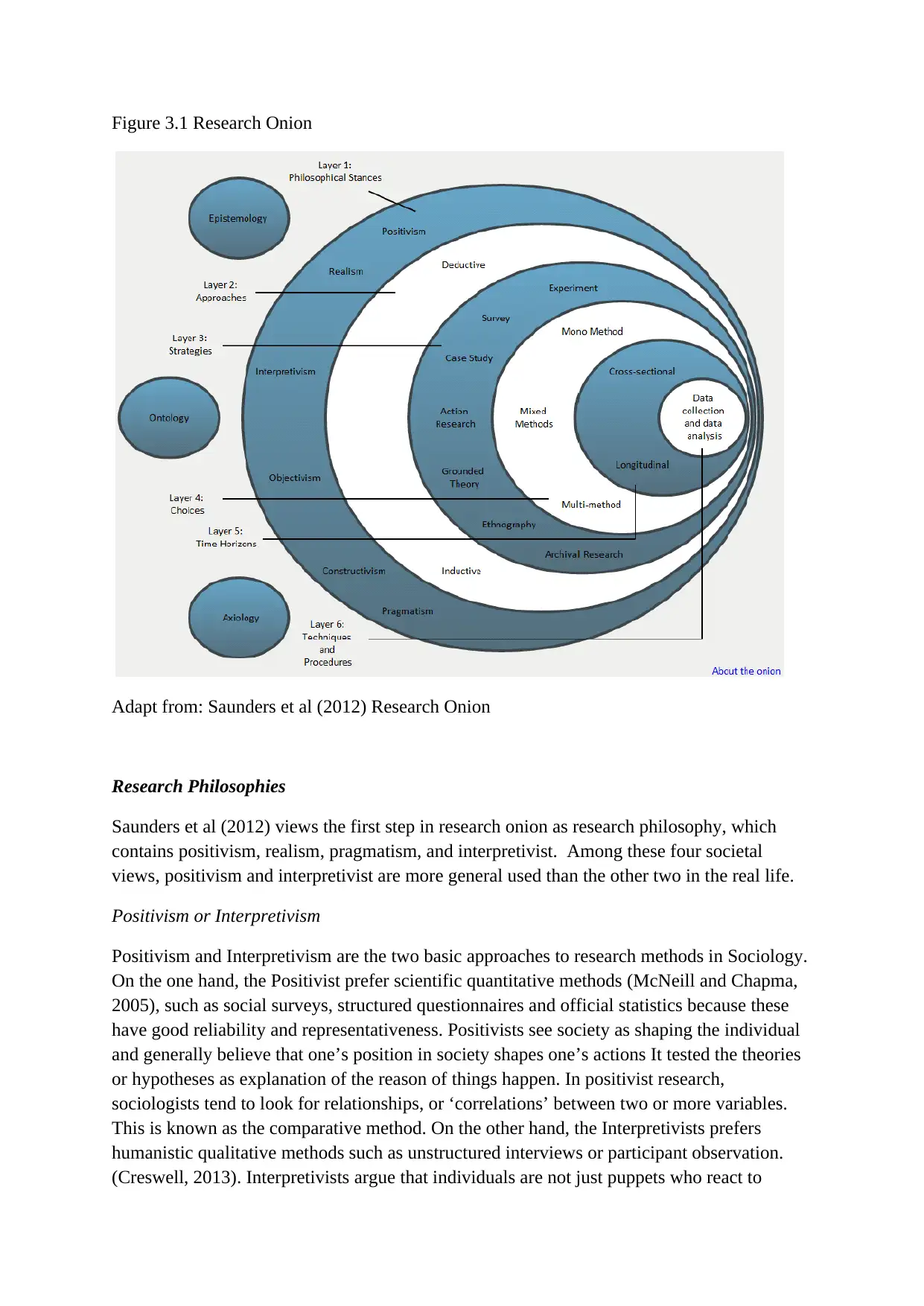

Research Philosophies

Saunders et al (2012) views the first step in research onion as research philosophy, which

contains positivism, realism, pragmatism, and interpretivist. Among these four societal

views, positivism and interpretivist are more general used than the other two in the real life.

Positivism or Interpretivism

Positivism and Interpretivism are the two basic approaches to research methods in Sociology.

On the one hand, the Positivist prefer scientific quantitative methods (McNeill and Chapma,

2005), such as social surveys, structured questionnaires and official statistics because these

have good reliability and representativeness. Positivists see society as shaping the individual

and generally believe that one’s position in society shapes one’s actions It tested the theories

or hypotheses as explanation of the reason of things happen. In positivist research,

sociologists tend to look for relationships, or ‘correlations’ between two or more variables.

This is known as the comparative method. On the other hand, the Interpretivists prefers

humanistic qualitative methods such as unstructured interviews or participant observation.

(Creswell, 2013). Interpretivists argue that individuals are not just puppets who react to

Adapt from: Saunders et al (2012) Research Onion

Research Philosophies

Saunders et al (2012) views the first step in research onion as research philosophy, which

contains positivism, realism, pragmatism, and interpretivist. Among these four societal

views, positivism and interpretivist are more general used than the other two in the real life.

Positivism or Interpretivism

Positivism and Interpretivism are the two basic approaches to research methods in Sociology.

On the one hand, the Positivist prefer scientific quantitative methods (McNeill and Chapma,

2005), such as social surveys, structured questionnaires and official statistics because these

have good reliability and representativeness. Positivists see society as shaping the individual

and generally believe that one’s position in society shapes one’s actions It tested the theories

or hypotheses as explanation of the reason of things happen. In positivist research,

sociologists tend to look for relationships, or ‘correlations’ between two or more variables.

This is known as the comparative method. On the other hand, the Interpretivists prefers

humanistic qualitative methods such as unstructured interviews or participant observation.

(Creswell, 2013). Interpretivists argue that individuals are not just puppets who react to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

external social forces as Positivists believe. According to Interpretivists individuals are

intricate and complex and different people experience and understand the same ‘objective

reality’ in very different ways and have their own, often very different, reasons for acting in

the world.Bryman (2012) thinks this approach can help to think beyond the existing

environment and may has bias judgement and understanding of social action.

Figure 3.2 Positivist vs. Interpretivist Beliefs

One advantage of it is the objective view held by researchers, which avoid influence toward

data collection (Matthnews and Ross, 2010). Another reason is the strictly stated and control

of time, which help the researcher deal with different step in limited time (Gratton and Jones,

2010). These two aspects lead to choose positivist approach in initial step.

Research Choices

To find out the beneficial research knowledge, it is necessary to realize the objectives through

choosing the effectiveness research typologies (Saunders et al, 2012).

Exploratory, Descriptive or Explanatory Research

The research is generally managed rely on the purpose of investigating, exploratory and

descriptive and explanatory are essential for research choice (McNabb, 2004). Exploratory

research permits the development of theories in areas where still has gap (Blumberg et al,

2011). Such research concentrates on development of universal knowledge instead of the

intricate and complex and different people experience and understand the same ‘objective

reality’ in very different ways and have their own, often very different, reasons for acting in

the world.Bryman (2012) thinks this approach can help to think beyond the existing

environment and may has bias judgement and understanding of social action.

Figure 3.2 Positivist vs. Interpretivist Beliefs

One advantage of it is the objective view held by researchers, which avoid influence toward

data collection (Matthnews and Ross, 2010). Another reason is the strictly stated and control

of time, which help the researcher deal with different step in limited time (Gratton and Jones,

2010). These two aspects lead to choose positivist approach in initial step.

Research Choices

To find out the beneficial research knowledge, it is necessary to realize the objectives through

choosing the effectiveness research typologies (Saunders et al, 2012).

Exploratory, Descriptive or Explanatory Research

The research is generally managed rely on the purpose of investigating, exploratory and

descriptive and explanatory are essential for research choice (McNabb, 2004). Exploratory

research permits the development of theories in areas where still has gap (Blumberg et al,

2011). Such research concentrates on development of universal knowledge instead of the

particular point (Mooi and Sarstedt, 2011). It is noteworthy that focus groups or techniques is

common research tool in the study (Collis and Hussey, 2009). Descriptive research usually

guarantee the description of data and characteristics of individual or phenomenon which

being interested in an area (Sekaran et al, 2003). Such kind of research uses surveys or

interviews to gather the essential data that explore the demonstration about the precise

description of a specific individual rather than creating a new hypothesis (Collis and Hussey,

2009). Rather than finding out or describing, explanatory research pursues to perceive the

meaning of causal relationship among variables, which also relate to causal research (Fisher

and Ziviani, 2004). It is used theories or hypotheses to understand the forces that caused an

accurate phenomenon to occur or change (Kothari, 2004). Questionnaire is one general way

to in explanatory research (Beri, 2007).

Because of the specific research objective, this dissertation has apply the explanatory

research that to gain insight of the relationship between Chinese students perception and the

UK HE by using the brand equity strategy.

Primary research or secondary research

Crowther and Lancaster (2012) recognized primary research and second research are the two

category of data collection. Because of different variables, Saunders et al (2012)

recommended that there are diversified approaches to collect data.

On the one hand, primary data attributes to self-report data through collecting data by

observation, experience, or reporting by gathering themselves (Walliman, 2011). In addition,

this kind of data show particular purpose of researchers towards studies area as well as

permitting unique data collection to rank the research objectives for achieving consistent

method. While according to the view of Strawarski and Phillips (2007), it needs a lot of time

and limited to the purpose of research at the same time.

On the other hand, Frankfort and Nachmias (1992) identified that the secondary data raised

from the remaining resource. Source It mainly from derived account such as websites, books

and newspapers. Bryman (2012) introduced that it can reduce cost and save time as well as

answering questions through analysing large scale information. On the contrast, this kind of

data cannot obtain quality towards reliable resources.

Qualitative Research or Quantitative Research

Goertz and Mahoney (2012) highlighted that the type and aim of research determine to

choose qualitative or quantitative research in the study. In terms of quantitative research, it

sets up the structure upon raw data figures and the description of numbers are numerical

measurement (Blumberg, 2011). Such study usually try to collect and analysis data,

frequencies and percentages to realize reliability and validity. Many techniques can apply to

collect quantitative data like questionnaires and structured interview (Creswell, 2014).

Conversely, qualitative research regards the conversation as one way to evoke knowledge

while not known with the logic explanation (Brinkmann, 2013). Nevertheless, it has

weakness in replicating studies as well as low transparency due to the relationship among

common research tool in the study (Collis and Hussey, 2009). Descriptive research usually

guarantee the description of data and characteristics of individual or phenomenon which

being interested in an area (Sekaran et al, 2003). Such kind of research uses surveys or

interviews to gather the essential data that explore the demonstration about the precise

description of a specific individual rather than creating a new hypothesis (Collis and Hussey,