Wearable Tech & Office Health: A Review of Pedometer Interventions

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|13

|4412

|197

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review explores the impact of pedometer interventions and wearable technology on the health and physical activity levels of office workers. It begins by defining physical activity and highlighting the global physical activity guidelines, emphasizing the disease and economic burden of physical inactivity. The review investigates the role of sedentary behavior and occupational factors in contributing to poor health outcomes. It further examines the potential benefits of physical activity interventions in the workplace, focusing on the effectiveness of pedometer-based programs and wearable technology in reducing sedentary time, improving cardio metabolic biomarkers, and increasing overall physical activity. The methodology section details the systematic approach used for the review, including the PICO framework and adherence to PRISMA guidelines. The objective is to determine whether wearable technology interventions improve cardio metabolic outcomes and increase physical activity levels among office workers, contributing to a better understanding of workplace health programs. Desklib provides access to this and other solved assignments.

Chapter 1

Introduction

Background:

1.1 Definition of physical activity

Physical activity is any movement of the body produced by muscles, which requires energy

outlay. This includes any movement that is done throughout the day except during lying down or

sitting still. For example; exercise, occupational work, housework, leisure time activity and

transportation (World Health Organization, 2018).

Physical activity can be categorized into light, moderate, or vigorous intensity level of physical

activity. Most health benefits have been associated with moderate to vigorous intensity physical

activity (National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability 1998; US Surgeon General

1996).

Light intensity physical activity does not cause noticeable increase in breathing rate and results

in small increase in energy expenditure, while moderate intensity physical activity (eg, brisk

walking), and vigorous physical activity (eg, jogging) both create noticeable increase in

breathing rate and energy expenditure (see glossary for further information).

Sedentary behavior indicate as the time spent lying or sitting and engaging in less than 30

minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week (Tremblay et al., 2018).

1.2 Physical activity guideline

There has been a dramatic increase in the rate of obesity in the western world. This has led to the

development of physical activity guidelines for the general public.

The Global physical activity Guidelines has recommended a minimum of 150-300 minutes of

moderate intensity physical activity per week, or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity physical

activity per week for adults aged 18-64 years. This recommendation has been proposed to gain

the health benefits along with reducing the risk of chronic illnesses (Who.int, 2018).

Additionally, World Health Organization recommended two or more days per week of a muscle

strengthening training involving main muscle groups. (Who.int, 2018).

1

Introduction

Background:

1.1 Definition of physical activity

Physical activity is any movement of the body produced by muscles, which requires energy

outlay. This includes any movement that is done throughout the day except during lying down or

sitting still. For example; exercise, occupational work, housework, leisure time activity and

transportation (World Health Organization, 2018).

Physical activity can be categorized into light, moderate, or vigorous intensity level of physical

activity. Most health benefits have been associated with moderate to vigorous intensity physical

activity (National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability 1998; US Surgeon General

1996).

Light intensity physical activity does not cause noticeable increase in breathing rate and results

in small increase in energy expenditure, while moderate intensity physical activity (eg, brisk

walking), and vigorous physical activity (eg, jogging) both create noticeable increase in

breathing rate and energy expenditure (see glossary for further information).

Sedentary behavior indicate as the time spent lying or sitting and engaging in less than 30

minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week (Tremblay et al., 2018).

1.2 Physical activity guideline

There has been a dramatic increase in the rate of obesity in the western world. This has led to the

development of physical activity guidelines for the general public.

The Global physical activity Guidelines has recommended a minimum of 150-300 minutes of

moderate intensity physical activity per week, or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity physical

activity per week for adults aged 18-64 years. This recommendation has been proposed to gain

the health benefits along with reducing the risk of chronic illnesses (Who.int, 2018).

Additionally, World Health Organization recommended two or more days per week of a muscle

strengthening training involving main muscle groups. (Who.int, 2018).

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1.3 Disease burden of physical inactivity

Physical inactivity is associated with poor health and well-being at all ages. It is considered to be

the fourth leading cause of death worldwide (Who.int, 2018), which leads it to be one of the

major public health concerns as it is estimated to cause 3.2 million mortalities annually, due to its

related diseases (Who.int, 2018).

One of the most significant challenges facing the global the global public health system is to

reverse the patterns of expanding physical inactivity that threaten the health and well-being of

the people. Individuals who are physically inactive are at 20-30% higher risk of dying compared

to individuals who are physical active (Who.int, 2018).

Physical inactivity is a lifestyle factor that is closely correlated with the development of many

chronic diseases. Hence, it is considered as the main intervention for primary and secondary

prevention of chronic disease (Durstine et al, 2013). Being physically active is essential for the

general health, beside the benefit in reducing the risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes

mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hyper-lipidemia, HTN, stroke, cancers, osteoarthritis

and depression (MacEwen, MacDonald and Burr, 2015). Who.int, (2018) estimated that physical

inactivity cause 10-16% cases of colorectal carcinoma, breast cancer and type2 diabetes mellitus

and approximately 22% of ischemic heart diseases in both men and women globally (Who.int,

2018).

In the United Kingdom, physical inactivity cause 17-18.7% cases of breast and colorectal

carcinoma, 13% of type 2 diabetes mellitus,10.5% of coronary heart diseases and 16.9% of

premature mortalities from all causes (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). It was presented that, women

spending at least 2 hours a week in moderate to vigorous activity can reduce the risk of breast

cancer by 5%, and up to 30% reduction in endometrial cancers (GOV.UK, 2018).

In addition, it was also reported by Weyerer (1992) that inactive individual have 3 times more

risk of developing moderate to severe depression than active individual (Weyerer, 1992), and

NICE guideline recommended, that individual with mild depression to be involved in a physical

activity program as a part of the treatment (GOV.UK, 2018).

1.4 Economic burden of physical inactivity

Statistics from 2009-2010 presented that physical inactivity direct cost to the United Kingdom

economy health care about £8.7 billion because of diagnosis of CVD and the total health care

cost on the economy was £18.9 billion (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). Most recent data collected by

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in 2013-2014 found that physical inactivity cost NHS

£455 million in England only (Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, 2018).

In 2010/2011, it was estimated that coronary heart disease (CHD) would cost the NHS over £6.7

billion a year in the UK (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018), while data of 2012 revealed that, NHS spent

2

Physical inactivity is associated with poor health and well-being at all ages. It is considered to be

the fourth leading cause of death worldwide (Who.int, 2018), which leads it to be one of the

major public health concerns as it is estimated to cause 3.2 million mortalities annually, due to its

related diseases (Who.int, 2018).

One of the most significant challenges facing the global the global public health system is to

reverse the patterns of expanding physical inactivity that threaten the health and well-being of

the people. Individuals who are physically inactive are at 20-30% higher risk of dying compared

to individuals who are physical active (Who.int, 2018).

Physical inactivity is a lifestyle factor that is closely correlated with the development of many

chronic diseases. Hence, it is considered as the main intervention for primary and secondary

prevention of chronic disease (Durstine et al, 2013). Being physically active is essential for the

general health, beside the benefit in reducing the risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes

mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hyper-lipidemia, HTN, stroke, cancers, osteoarthritis

and depression (MacEwen, MacDonald and Burr, 2015). Who.int, (2018) estimated that physical

inactivity cause 10-16% cases of colorectal carcinoma, breast cancer and type2 diabetes mellitus

and approximately 22% of ischemic heart diseases in both men and women globally (Who.int,

2018).

In the United Kingdom, physical inactivity cause 17-18.7% cases of breast and colorectal

carcinoma, 13% of type 2 diabetes mellitus,10.5% of coronary heart diseases and 16.9% of

premature mortalities from all causes (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). It was presented that, women

spending at least 2 hours a week in moderate to vigorous activity can reduce the risk of breast

cancer by 5%, and up to 30% reduction in endometrial cancers (GOV.UK, 2018).

In addition, it was also reported by Weyerer (1992) that inactive individual have 3 times more

risk of developing moderate to severe depression than active individual (Weyerer, 1992), and

NICE guideline recommended, that individual with mild depression to be involved in a physical

activity program as a part of the treatment (GOV.UK, 2018).

1.4 Economic burden of physical inactivity

Statistics from 2009-2010 presented that physical inactivity direct cost to the United Kingdom

economy health care about £8.7 billion because of diagnosis of CVD and the total health care

cost on the economy was £18.9 billion (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). Most recent data collected by

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in 2013-2014 found that physical inactivity cost NHS

£455 million in England only (Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk, 2018).

In 2010/2011, it was estimated that coronary heart disease (CHD) would cost the NHS over £6.7

billion a year in the UK (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018), while data of 2012 revealed that, NHS spent

2

£8.8 billion in the direct (treatment, intervention and complication) NHS patient care for type 2

diabetes mellitus patients and estimated approximately £13 billion for the indirect (e.g loss of

productivity) cost (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). The review of 2008/2009 statistics showed that

NHS spent £5.13 billion on all cancer treatments (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). Moreover, diseases

related to overweight and obesity cost the NHS over £5 billion in 2006/07 (Ssehsactive.org.uk,

2018). Hence, these figures give estimation regarding the direct and indirect cost implication of

being physically inactive and suggest the need to implement interventions to promote physical

activity.

1.5 Sedentary behavior and Health

Population in the UK are about 20% inactive now than 1960s, and its estimated by 2030,

approximately 35% of them will be physically inactive, if the existing trend of inactivity

continues (GOV.UK, 2018).There are many factors found to be influencing physical inactivity.

One of the major cause is the domination of passive modes of transportation, which is associated

with decreased level of activity (GOV.UK, 2018) as well as an increase in the sedentary behavior

during occupational domestic activaties (GOV.UK, 2018). Furthermore, increase in urbanization

(which leads to several environmental factors) may discourage involvement in physical activity

E.g: air pollution, increase in traffic, violence and lack of sidewalks, parks, and sports/recreation

facilities. (Who.int, 2018).

1.6 Occupational related illness

The work environment and characteristics of work also has a major role in influencing health

outcome of people. Majority of existing sedentary behavior is linked with the large proportion of

employees spending the day sitting in front of desktop computers (Carr et al., 2016).

Since 1950, sedentary occupations have increased for approximately 83%, and it accounts for

about 43% of jobs in the U.S (Carr et al., 2016), and 70% in the UK (GOV.UK, 2018).

More precisely, time spent sitting is significantly associated with increase in the risks of

developing metabolic syndrome, obesity, and type-2 diabetes mellitus (MacEwen, MacDonald

and Burr, 2015). In addition, upper body musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders were also

associated with sedentary computer work (Carr et al., 2016). It has been found that 1 in 3 of the

working age individuals have a minimum of one long term chronic disease and 1 in 7 having

more than one chronic disease (GOV.UK, 2018).

Hence, workplace has become a main target for health promotion programs intending to increase

physical activity level and prevent chronic illnesses (WHO/WEF 2008).

3

diabetes mellitus patients and estimated approximately £13 billion for the indirect (e.g loss of

productivity) cost (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). The review of 2008/2009 statistics showed that

NHS spent £5.13 billion on all cancer treatments (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). Moreover, diseases

related to overweight and obesity cost the NHS over £5 billion in 2006/07 (Ssehsactive.org.uk,

2018). Hence, these figures give estimation regarding the direct and indirect cost implication of

being physically inactive and suggest the need to implement interventions to promote physical

activity.

1.5 Sedentary behavior and Health

Population in the UK are about 20% inactive now than 1960s, and its estimated by 2030,

approximately 35% of them will be physically inactive, if the existing trend of inactivity

continues (GOV.UK, 2018).There are many factors found to be influencing physical inactivity.

One of the major cause is the domination of passive modes of transportation, which is associated

with decreased level of activity (GOV.UK, 2018) as well as an increase in the sedentary behavior

during occupational domestic activaties (GOV.UK, 2018). Furthermore, increase in urbanization

(which leads to several environmental factors) may discourage involvement in physical activity

E.g: air pollution, increase in traffic, violence and lack of sidewalks, parks, and sports/recreation

facilities. (Who.int, 2018).

1.6 Occupational related illness

The work environment and characteristics of work also has a major role in influencing health

outcome of people. Majority of existing sedentary behavior is linked with the large proportion of

employees spending the day sitting in front of desktop computers (Carr et al., 2016).

Since 1950, sedentary occupations have increased for approximately 83%, and it accounts for

about 43% of jobs in the U.S (Carr et al., 2016), and 70% in the UK (GOV.UK, 2018).

More precisely, time spent sitting is significantly associated with increase in the risks of

developing metabolic syndrome, obesity, and type-2 diabetes mellitus (MacEwen, MacDonald

and Burr, 2015). In addition, upper body musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders were also

associated with sedentary computer work (Carr et al., 2016). It has been found that 1 in 3 of the

working age individuals have a minimum of one long term chronic disease and 1 in 7 having

more than one chronic disease (GOV.UK, 2018).

Hence, workplace has become a main target for health promotion programs intending to increase

physical activity level and prevent chronic illnesses (WHO/WEF 2008).

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1.7 Benefits of physical activity interventions in the workplace

Introducing physical activity programs in the workplace can lead to varying success rates in the

reduction of employee absence over a year. Additional benefit of the physical activity program is

that it would lead to an increase in physical activity and decrease in sedentary time (WHO/WEF

2008; Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). It was elaborated that, if the program is 1% effective in

reducing the number of absenteeism’s, the employers will have possibility to save between

£2,870 and £6,244 every year. If the program was 50% effective in increasing physical activity

level among employees and decrease in number of absentees, the employer will save over

£312,217 per year (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018).

Surveys such as that conducted by KATZMARZYK et al. (2009) showed that individual who

spends more time sitting have increased risk of death more than who stands and walk during

worktime, despite their physical activity level. An independent association between body mass

index (BMI) and both deaths and spending time sitting is also seen (KATZMARZYK et al.,

2009).

To date, a considerable amount of literatures have been published that reveals overall

effectiveness of existing workplace interventions in reducing sedentary time, improving cardio-

metabolic biomarkers and increasing physical activity. These studies have examined different

types of interventions including the use of wearable technology devices, such as pedometers in

promoting physical activity. Nevertheless, a trend of step counting has come up targeting ‘10,000

step per day’ with the increase use of pedometers, which has been implemented in numerous

intervention studies. One example includes implementation of a multi- approach physical activity

intervention in a big community “10,000 Steps Ghent” which offered an opportunity to assess

the outcomes of a whole-community physical activity intervention on sitting time (De Cocker et

al., 2007).

In recent years, many studies have focused on the usage and the feasibility of sit-stand and

treadmill workstations, which yielded positive physical and psychological outcome as seen in the

systematic review study done by MacEwen, MacDonald and Burr (2015). Loitz et al. (2015)

conducted a review of different types of workplace interventions, which included active

workstations, educational, counseling and challenging or competition interventions and revealed

a significant effect of different interventions on decreasing sedentary time and increasing

physical activity.

A number of researchers have reported from different trials of pedometer based interventions an

effectiveness of pedometer in increasing level of physical activity and its positive effect on the

cardio-metabolic bio markers as it delivers direct, detailed feedback on the levels of physical

activity. Such interventions can motivate individuals to increase their physical activity over time

(Matevey et al., 2006).

4

Introducing physical activity programs in the workplace can lead to varying success rates in the

reduction of employee absence over a year. Additional benefit of the physical activity program is

that it would lead to an increase in physical activity and decrease in sedentary time (WHO/WEF

2008; Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018). It was elaborated that, if the program is 1% effective in

reducing the number of absenteeism’s, the employers will have possibility to save between

£2,870 and £6,244 every year. If the program was 50% effective in increasing physical activity

level among employees and decrease in number of absentees, the employer will save over

£312,217 per year (Ssehsactive.org.uk, 2018).

Surveys such as that conducted by KATZMARZYK et al. (2009) showed that individual who

spends more time sitting have increased risk of death more than who stands and walk during

worktime, despite their physical activity level. An independent association between body mass

index (BMI) and both deaths and spending time sitting is also seen (KATZMARZYK et al.,

2009).

To date, a considerable amount of literatures have been published that reveals overall

effectiveness of existing workplace interventions in reducing sedentary time, improving cardio-

metabolic biomarkers and increasing physical activity. These studies have examined different

types of interventions including the use of wearable technology devices, such as pedometers in

promoting physical activity. Nevertheless, a trend of step counting has come up targeting ‘10,000

step per day’ with the increase use of pedometers, which has been implemented in numerous

intervention studies. One example includes implementation of a multi- approach physical activity

intervention in a big community “10,000 Steps Ghent” which offered an opportunity to assess

the outcomes of a whole-community physical activity intervention on sitting time (De Cocker et

al., 2007).

In recent years, many studies have focused on the usage and the feasibility of sit-stand and

treadmill workstations, which yielded positive physical and psychological outcome as seen in the

systematic review study done by MacEwen, MacDonald and Burr (2015). Loitz et al. (2015)

conducted a review of different types of workplace interventions, which included active

workstations, educational, counseling and challenging or competition interventions and revealed

a significant effect of different interventions on decreasing sedentary time and increasing

physical activity.

A number of researchers have reported from different trials of pedometer based interventions an

effectiveness of pedometer in increasing level of physical activity and its positive effect on the

cardio-metabolic bio markers as it delivers direct, detailed feedback on the levels of physical

activity. Such interventions can motivate individuals to increase their physical activity over time

(Matevey et al., 2006).

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

World Economic Forum and World Health Organization (WHO/WEF 2008) have

recommended that more research is required to reinforce current

understanding of work place health programs, especially on the

effectiveness and the usage of simple gadgets.

Hence, the objective of this literature review to explore existing literatures examining the amount

of health benefits from the use of pedometer interventions and to determine whether wearable

technology intervention improves cardio metabolic outcomes in office workers or not. The

research also aims to analyze whether wearable technology intervention increases the level of

physical activity in office workers or not.

5

recommended that more research is required to reinforce current

understanding of work place health programs, especially on the

effectiveness and the usage of simple gadgets.

Hence, the objective of this literature review to explore existing literatures examining the amount

of health benefits from the use of pedometer interventions and to determine whether wearable

technology intervention improves cardio metabolic outcomes in office workers or not. The

research also aims to analyze whether wearable technology intervention increases the level of

physical activity in office workers or not.

5

Chapter 2.

Methodology

2.1 Study design:

As the main purpose of this study is to explore the benefit of different pedometer intervention on

increasing level of physical activity among workers, secondary research design is considered

appropriate for this research design. Secondary research design is appropriate when the purpose

is to clarify the research question and understand the applicability of past research in a large

scale (Walliman 2017). Literature review using systematic method has been used to retrieve both

qualitative and quantitative research papers on the research topic. The main benefits of using this

type of research design is that it is a rigorous and transparent form of literature review and it has

the potential to generate a robust answer to a research question (Mallett et al. 2012) The step that

has been used in conducting a systematic review is deconstruction of research question using the

population, intervention, outcome and comparator (PICO). The next step was to develop search

strategy and retrieve relevant articles from academic and institutional databases. Inclusion and

exclusion criteria were defined and the detailed process to screen and select research articles

were provided. The final part of the methodology will define the approach needed to directly

compare and interpret results and determine the implications for application in target setting.

To enhance the quality of reporting of the research, the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed. It is an evidence based

document that defines the list of items that is necessary while reporting in systematic (Moher et

al. 2015). Hence, adherence to the PRISMA guideline can promote transparency of the work.

2.2 PICO question:

The first step of the literature review is to deconstruct the research question and define the PICO

for the study. Based on the analysis of research objective, it can be said that the main question

for the review are as follows:

How effective is pedometer intervention and wearable technology intervention in

improving cardio metabolic outcome and increasing physical activity in office workers compared

to no intervention?

After the deconstruction of the research question, the following information emerged:

P (Population): Office workers or employee

I (Intervention): pedometer intervention and wearable technology intervention

C (Comparator): no intervention

Outcome: Improving cardio metabolic outcome and increasing physical activity

The deconstruction of the question will help to define search strategy and identify appropriate

terms that can be used for the search process. This has informed developing inclusion and

exclusion criteria too.

2.3 Eligibility criteria:

6

Methodology

2.1 Study design:

As the main purpose of this study is to explore the benefit of different pedometer intervention on

increasing level of physical activity among workers, secondary research design is considered

appropriate for this research design. Secondary research design is appropriate when the purpose

is to clarify the research question and understand the applicability of past research in a large

scale (Walliman 2017). Literature review using systematic method has been used to retrieve both

qualitative and quantitative research papers on the research topic. The main benefits of using this

type of research design is that it is a rigorous and transparent form of literature review and it has

the potential to generate a robust answer to a research question (Mallett et al. 2012) The step that

has been used in conducting a systematic review is deconstruction of research question using the

population, intervention, outcome and comparator (PICO). The next step was to develop search

strategy and retrieve relevant articles from academic and institutional databases. Inclusion and

exclusion criteria were defined and the detailed process to screen and select research articles

were provided. The final part of the methodology will define the approach needed to directly

compare and interpret results and determine the implications for application in target setting.

To enhance the quality of reporting of the research, the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed. It is an evidence based

document that defines the list of items that is necessary while reporting in systematic (Moher et

al. 2015). Hence, adherence to the PRISMA guideline can promote transparency of the work.

2.2 PICO question:

The first step of the literature review is to deconstruct the research question and define the PICO

for the study. Based on the analysis of research objective, it can be said that the main question

for the review are as follows:

How effective is pedometer intervention and wearable technology intervention in

improving cardio metabolic outcome and increasing physical activity in office workers compared

to no intervention?

After the deconstruction of the research question, the following information emerged:

P (Population): Office workers or employee

I (Intervention): pedometer intervention and wearable technology intervention

C (Comparator): no intervention

Outcome: Improving cardio metabolic outcome and increasing physical activity

The deconstruction of the question will help to define search strategy and identify appropriate

terms that can be used for the search process. This has informed developing inclusion and

exclusion criteria too.

2.3 Eligibility criteria:

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Defining eligibility criteria is necessary to get necessary guidance regarding the approach used to

search for relevant research papers for the review.

Studies were evaluated for eligibility according to the following inclusion criteria:

1. Population: Only those research papers were reviewed that has taken office workers or

employees as the main research participant. Adults above 18 years were taken as the age

limit so that children and adolescent group is not taken for the review.

2. Intervention: Any intervention that used used wearable technology or pedometer were

included in the review

3. Outcome: Only thus studies were included which reported about level of physical activity

and cardiometabolic outcome

4. Time period: Only those studies were included in the literature review which were

published within 2008 to 2018

5. Types of studies: Both qualitative and quantitative research were included if they met the

above inclusion criteria.

6. Language: All research papers must be published in English.

2.4 Exclusion criteria:

(1) Studies which included beside wearable technology device another intervention.

(2) Studies which used the wearable device for measuring only were excluded.

(3) Studies which were not office-based workplace were excluded.

2.5 Types of outcome measures:

2.5.1 Primary outcomes:

The primary outcome for this literature was measuring the cardiovascular

biomarkers

o Biochemical measures for e.g; blood cholesterol (total

cholesterol, LDL, HDL, blood triglycerides) and blood glucose.

o Anthropometric measures such as; body mass index and body

fat.

o Blood pressure for example; diastolic blood pressure and systolic

blood pressure.

2.5.2 Secondary outcomes:

The secondary outcome is measuring the level of physical activity, self-

reported, using personal calendar or website diary such as;

www.peifirststep.ca.

7

search for relevant research papers for the review.

Studies were evaluated for eligibility according to the following inclusion criteria:

1. Population: Only those research papers were reviewed that has taken office workers or

employees as the main research participant. Adults above 18 years were taken as the age

limit so that children and adolescent group is not taken for the review.

2. Intervention: Any intervention that used used wearable technology or pedometer were

included in the review

3. Outcome: Only thus studies were included which reported about level of physical activity

and cardiometabolic outcome

4. Time period: Only those studies were included in the literature review which were

published within 2008 to 2018

5. Types of studies: Both qualitative and quantitative research were included if they met the

above inclusion criteria.

6. Language: All research papers must be published in English.

2.4 Exclusion criteria:

(1) Studies which included beside wearable technology device another intervention.

(2) Studies which used the wearable device for measuring only were excluded.

(3) Studies which were not office-based workplace were excluded.

2.5 Types of outcome measures:

2.5.1 Primary outcomes:

The primary outcome for this literature was measuring the cardiovascular

biomarkers

o Biochemical measures for e.g; blood cholesterol (total

cholesterol, LDL, HDL, blood triglycerides) and blood glucose.

o Anthropometric measures such as; body mass index and body

fat.

o Blood pressure for example; diastolic blood pressure and systolic

blood pressure.

2.5.2 Secondary outcomes:

The secondary outcome is measuring the level of physical activity, self-

reported, using personal calendar or website diary such as;

www.peifirststep.ca.

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

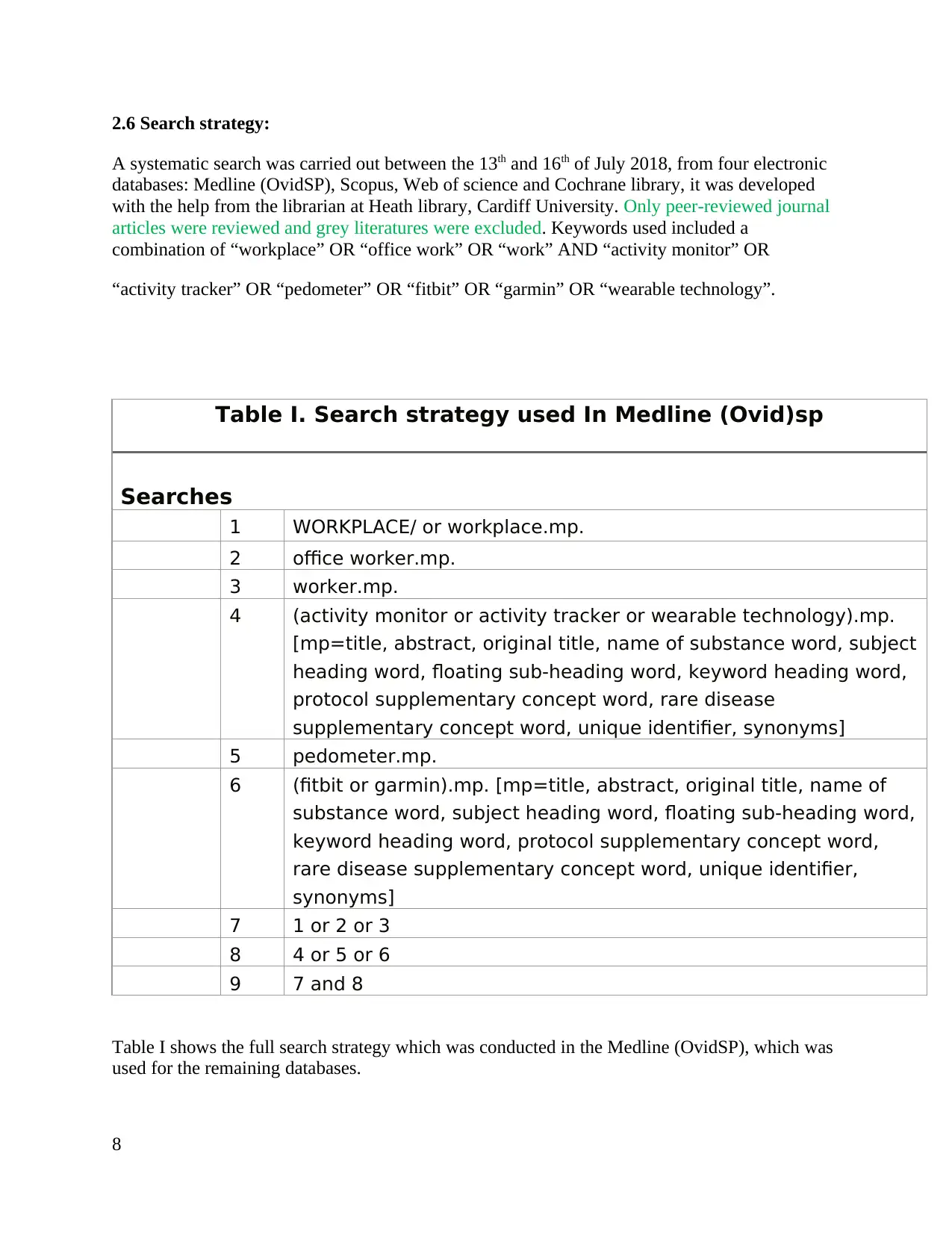

2.6 Search strategy:

A systematic search was carried out between the 13th and 16th of July 2018, from four electronic

databases: Medline (OvidSP), Scopus, Web of science and Cochrane library, it was developed

with the help from the librarian at Heath library, Cardiff University. Only peer-reviewed journal

articles were reviewed and grey literatures were excluded. Keywords used included a

combination of “workplace” OR “office work” OR “work” AND “activity monitor” OR

“activity tracker” OR “pedometer” OR “fitbit” OR “garmin” OR “wearable technology”.

Table I. Search strategy used In Medline (Ovid)sp

Searches

1 WORKPLACE/ or workplace.mp.

2 office worker.mp.

3 worker.mp.

4 (activity monitor or activity tracker or wearable technology).mp.

[mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject

heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word,

protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease

supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

5 pedometer.mp.

6 (fitbit or garmin).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of

substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word,

keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word,

rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier,

synonyms]

7 1 or 2 or 3

8 4 or 5 or 6

9 7 and 8

Table I shows the full search strategy which was conducted in the Medline (OvidSP), which was

used for the remaining databases.

8

A systematic search was carried out between the 13th and 16th of July 2018, from four electronic

databases: Medline (OvidSP), Scopus, Web of science and Cochrane library, it was developed

with the help from the librarian at Heath library, Cardiff University. Only peer-reviewed journal

articles were reviewed and grey literatures were excluded. Keywords used included a

combination of “workplace” OR “office work” OR “work” AND “activity monitor” OR

“activity tracker” OR “pedometer” OR “fitbit” OR “garmin” OR “wearable technology”.

Table I. Search strategy used In Medline (Ovid)sp

Searches

1 WORKPLACE/ or workplace.mp.

2 office worker.mp.

3 worker.mp.

4 (activity monitor or activity tracker or wearable technology).mp.

[mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject

heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word,

protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease

supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

5 pedometer.mp.

6 (fitbit or garmin).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of

substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word,

keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word,

rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier,

synonyms]

7 1 or 2 or 3

8 4 or 5 or 6

9 7 and 8

Table I shows the full search strategy which was conducted in the Medline (OvidSP), which was

used for the remaining databases.

8

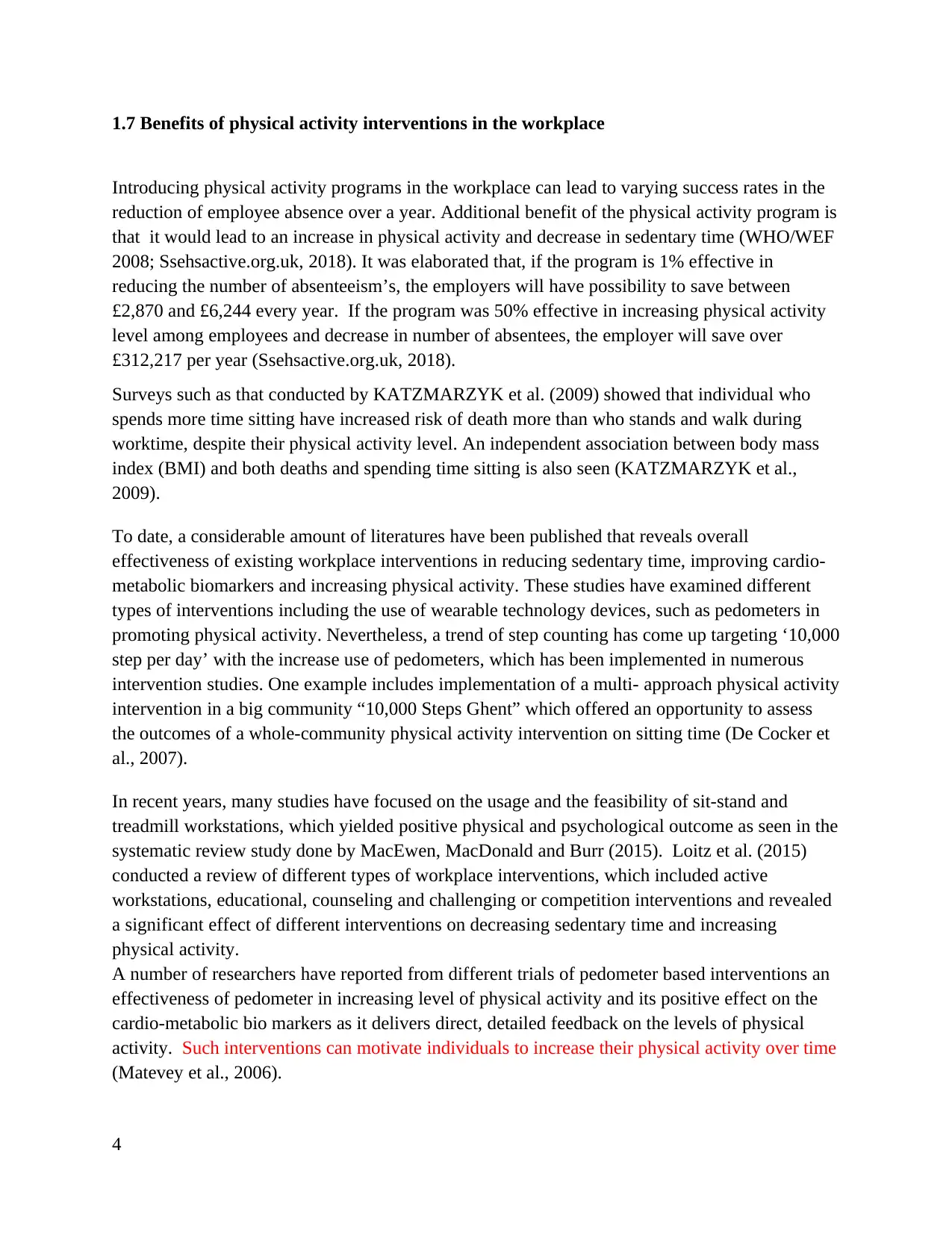

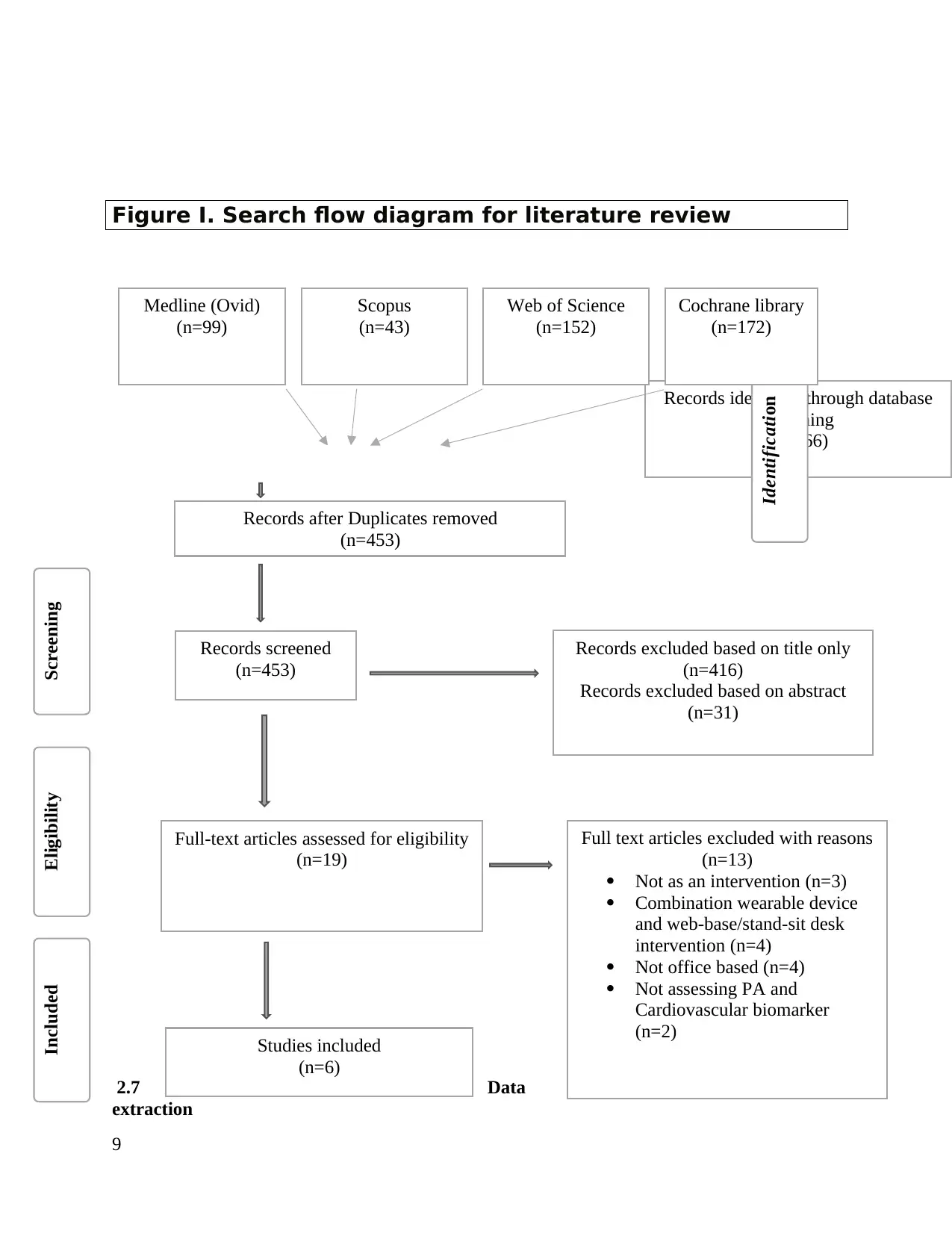

Figure I. Search flow diagram for literature review

2.7 Data

extraction

9

Records identified through database

searching

(n=466)

Studies included

(n=6)

Records after Duplicates removed

(n=453)

Records screened

(n=453)

Full text articles excluded with reasons

(n=13)

Not as an intervention (n=3)

Combination wearable device

and web-base/stand-sit desk

intervention (n=4)

Not office based (n=4)

Not assessing PA and

Cardiovascular biomarker

(n=2)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n=19)

Records excluded based on title only

(n=416)

Records excluded based on abstract

(n=31)

Identification

ScreeningEligibilityIncluded

Medline (Ovid)

(n=99)

Scopus

(n=43)

Web of Science

(n=152)

Cochrane library

(n=172)

2.7 Data

extraction

9

Records identified through database

searching

(n=466)

Studies included

(n=6)

Records after Duplicates removed

(n=453)

Records screened

(n=453)

Full text articles excluded with reasons

(n=13)

Not as an intervention (n=3)

Combination wearable device

and web-base/stand-sit desk

intervention (n=4)

Not office based (n=4)

Not assessing PA and

Cardiovascular biomarker

(n=2)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n=19)

Records excluded based on title only

(n=416)

Records excluded based on abstract

(n=31)

Identification

ScreeningEligibilityIncluded

Medline (Ovid)

(n=99)

Scopus

(n=43)

Web of Science

(n=152)

Cochrane library

(n=172)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Data extraction was done by developing a summary table and extracting information related to

research design, participant, intervention type, outcome and findings.

2.8 Study selection:

After entering the search terms in relevant databases, all the studies were screening according to title and

abstract. Studies were included for screening if they were in relevance with the research question. Once relevant

papers were identified, the remaining articles were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final

eligibility criteria was to ensure that appropriate research design was used and any disagreement regarding exclusion

was discussed with other research members. In this way, only those studies were included for which consensus was

achieved. The details for this have been provided in the result section.

2.9 Data analysis:

The assessment of rigor for the selected studies was done using validated Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. As

both quantitative and qualitative papers were included in the literature review, different data analysis method was

taken for qualitative and quantitative papers. For quantitative data, statistical test like correlation test was done to

find relationship between two quantitative variables used in the study. In addition, for papers using qualitative

approach, data analyse was done by finding common themes from the study and using those theme to makes

conclusion about the impact of the chosen intervention on level of physical activities among employee.

Chapter 3: Results

Results:

Literature search yielded 466 studies. Initially, the articles were selected by screening the titles,

screening the abstracts for information about the outcomes and the intervention, and exploring

the entire paper, if the title and abstract did not specify enough information to decide if it met the

inclusion criteria. articles which have not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Nineteen papers selected, thirteen were excluded after exploring entire paper, three of the

article’s pedometer was not used as an intervention, four studies had a combination of wearable

device with other interventions such as: web-based intervention and sit-stand desk, four studies

were not office-based intervention and two studies did not assess physical activity and

cardiovascular biomarker as their primary and secondary outcomes. Reporting six studies, met

the inclusion criteria. Additional searches were done from the included articles

references.

Studies included in this review are which having pedometer as the only

component of intervention but was reinforced by additional components of

the intervention such as; diaries, step counts or rewards in order to increase

the motivation.

10

research design, participant, intervention type, outcome and findings.

2.8 Study selection:

After entering the search terms in relevant databases, all the studies were screening according to title and

abstract. Studies were included for screening if they were in relevance with the research question. Once relevant

papers were identified, the remaining articles were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final

eligibility criteria was to ensure that appropriate research design was used and any disagreement regarding exclusion

was discussed with other research members. In this way, only those studies were included for which consensus was

achieved. The details for this have been provided in the result section.

2.9 Data analysis:

The assessment of rigor for the selected studies was done using validated Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool. As

both quantitative and qualitative papers were included in the literature review, different data analysis method was

taken for qualitative and quantitative papers. For quantitative data, statistical test like correlation test was done to

find relationship between two quantitative variables used in the study. In addition, for papers using qualitative

approach, data analyse was done by finding common themes from the study and using those theme to makes

conclusion about the impact of the chosen intervention on level of physical activities among employee.

Chapter 3: Results

Results:

Literature search yielded 466 studies. Initially, the articles were selected by screening the titles,

screening the abstracts for information about the outcomes and the intervention, and exploring

the entire paper, if the title and abstract did not specify enough information to decide if it met the

inclusion criteria. articles which have not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Nineteen papers selected, thirteen were excluded after exploring entire paper, three of the

article’s pedometer was not used as an intervention, four studies had a combination of wearable

device with other interventions such as: web-based intervention and sit-stand desk, four studies

were not office-based intervention and two studies did not assess physical activity and

cardiovascular biomarker as their primary and secondary outcomes. Reporting six studies, met

the inclusion criteria. Additional searches were done from the included articles

references.

Studies included in this review are which having pedometer as the only

component of intervention but was reinforced by additional components of

the intervention such as; diaries, step counts or rewards in order to increase

the motivation.

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Reference’s:

1- Who.int. (2018). WHO | Physical Activity and Adults. [online] Available at:

http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/ [Accessed 12 Jul. 2018].

2- Carr, L., Leonhard, C., Tucker, S., Fethke, N., Benzo, R. and Gerr, F. (2016). Total Worker

Health Intervention Increases Activity of Sedentary Workers. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 50(1), pp.9-17.

3- MacEwen, B., MacDonald, D. and Burr, J. (2015). A systematic review of standing and

treadmill desks in the workplace. Preventive Medicine, 70, pp.50-58.

4- KATZMARZYK, P., CHURCH, T., CRAIG, C. and BOUCHARD, C. (2009). Sitting Time

and Mortality from All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer. Medicine & Science in

Sports & Exercise, 41(5), pp.998-1005.

5- De Cocker, K., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Brown, W. and Cardon, G. (2008). The effect of a

pedometer-based physical activity intervention on sitting time. Preventive Medicine, 47(2),

pp.179-181.

6- De Cocker, K., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Brown, W. and Cardon, G. (2007). Effects of “10,000

Steps Ghent”: A Whole-Community Intervention. [online] 33(6), pp.455-463. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.037 [Accessed 12 Jul. 2018].

7- Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. (2018). [online] Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/524234/Physical_inactivity_costs_to_CCGs.pdf [Accessed 18 Jul. 2018].

11

1- Who.int. (2018). WHO | Physical Activity and Adults. [online] Available at:

http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/ [Accessed 12 Jul. 2018].

2- Carr, L., Leonhard, C., Tucker, S., Fethke, N., Benzo, R. and Gerr, F. (2016). Total Worker

Health Intervention Increases Activity of Sedentary Workers. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 50(1), pp.9-17.

3- MacEwen, B., MacDonald, D. and Burr, J. (2015). A systematic review of standing and

treadmill desks in the workplace. Preventive Medicine, 70, pp.50-58.

4- KATZMARZYK, P., CHURCH, T., CRAIG, C. and BOUCHARD, C. (2009). Sitting Time

and Mortality from All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer. Medicine & Science in

Sports & Exercise, 41(5), pp.998-1005.

5- De Cocker, K., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Brown, W. and Cardon, G. (2008). The effect of a

pedometer-based physical activity intervention on sitting time. Preventive Medicine, 47(2),

pp.179-181.

6- De Cocker, K., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Brown, W. and Cardon, G. (2007). Effects of “10,000

Steps Ghent”: A Whole-Community Intervention. [online] 33(6), pp.455-463. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.037 [Accessed 12 Jul. 2018].

7- Assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. (2018). [online] Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/524234/Physical_inactivity_costs_to_CCGs.pdf [Accessed 18 Jul. 2018].

11

8- Ssehsactive.org.uk. (2018). [online] Available at:

http://www.ssehsactive.org.uk/userfiles/Documents/eonomiccosts.pdf [Accessed 18 Jul.

2018].

9- Weyerer, S. (1992). Physical Inactivity and Depression in the Community. International

Journal of Sports Medicine, 13(06), pp.492-496.

10- GOV.UK. (2018). Health matters: getting every adult active every day. [online] Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-

day/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day [Accessed 18 Jul. 2018].

11- Who.int. (2018). WHO | Physical Inactivity: A Global Public Health Problem. [online]

Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/ [Accessed 18

Jul. 2018].

12- Loitz, C., Potter, R., Walker, J., McLeod, N. and Johnston, N. (2015). The effectiveness of

workplace interventions to increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behaviour in

adults: protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 4(1).

13- Matevey, C., Rogers, L., Dawson, E. and Tudor-Locke, C. (2006). Lack of Reactivity During

Pedometer Self-Monitoring in Adults. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise

Science, 10(1), pp.1-11.

14- World Health Organization. (2018). Physical Activity. [online] Available at:

https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/

15- World Health Organization/World Economic Forum (WHO/WEF). Preventing

noncommunicable diseases in the workplace through diet and physical activity: WHO/World

Economic Forum report of a joint event. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

16- Durstine, J.L., Gordon, B., Wang, Z. and Luo, X., 2013. Chronic disease and the link to

physical activity. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 2(1), pp.3-11.

17- Mallett, R., Hagen-Zanker, J., Slater, R. and Duvendack, M., 2012. The benefits and

challenges of using systematic reviews in international development research. Journal of

development effectiveness, 4(3), pp.445-455.

18- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P. and

Stewart, L.A., 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), p.1.

12

http://www.ssehsactive.org.uk/userfiles/Documents/eonomiccosts.pdf [Accessed 18 Jul.

2018].

9- Weyerer, S. (1992). Physical Inactivity and Depression in the Community. International

Journal of Sports Medicine, 13(06), pp.492-496.

10- GOV.UK. (2018). Health matters: getting every adult active every day. [online] Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-

day/health-matters-getting-every-adult-active-every-day [Accessed 18 Jul. 2018].

11- Who.int. (2018). WHO | Physical Inactivity: A Global Public Health Problem. [online]

Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/ [Accessed 18

Jul. 2018].

12- Loitz, C., Potter, R., Walker, J., McLeod, N. and Johnston, N. (2015). The effectiveness of

workplace interventions to increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behaviour in

adults: protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 4(1).

13- Matevey, C., Rogers, L., Dawson, E. and Tudor-Locke, C. (2006). Lack of Reactivity During

Pedometer Self-Monitoring in Adults. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise

Science, 10(1), pp.1-11.

14- World Health Organization. (2018). Physical Activity. [online] Available at:

https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/

15- World Health Organization/World Economic Forum (WHO/WEF). Preventing

noncommunicable diseases in the workplace through diet and physical activity: WHO/World

Economic Forum report of a joint event. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

16- Durstine, J.L., Gordon, B., Wang, Z. and Luo, X., 2013. Chronic disease and the link to

physical activity. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 2(1), pp.3-11.

17- Mallett, R., Hagen-Zanker, J., Slater, R. and Duvendack, M., 2012. The benefits and

challenges of using systematic reviews in international development research. Journal of

development effectiveness, 4(3), pp.445-455.

18- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P. and

Stewart, L.A., 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), p.1.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.