Obesity in Wolverhampton: Epidemiology, Health Determinants, and Data

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/15

|13

|5263

|201

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of obesity in Wolverhampton, examining its epidemiology, determinants of health, and relevant statistical data. It begins by defining obesity and highlighting its global impact, linking it to various health conditions and increased healthcare costs. The report then delves into the causes and risk factors associated with obesity, including genetic, epigenetic, and environmental influences, with specific data from the National Health Service (NHS) Digital and the City of Wolverhampton Council. It emphasizes the role of diet, physical exercise, and socioeconomic factors in contributing to obesity, particularly in underprivileged areas. Furthermore, the report outlines current policies and strategies in place to address obesity, focusing on behavior change, opportunistic interventions, tailored weight management programs, social prescribing, and surgical procedures. It also stresses the importance of reducing health disparities and adopting holistic approaches to community health improvement. The report concludes by underscoring the need for continued efforts to combat obesity and promote healthier lifestyles in Wolverhampton.

Obesity in Wolverhampton

Contents

A. The Epidemiology of Obesity...............................................................................................................2

B. Determinants of Health.......................................................................................................................5

Understanding the causes of obesity......................................................................................................5

Obesity risk factors and who is most affected by them...........................................................................5

Diet and food environment.....................................................................................................................5

Physical exercise......................................................................................................................................5

Obesity policy and strategy currently in place.........................................................................................5

Supporting change in behaviour..............................................................................................................6

Interventions based on opportunities.....................................................................................................6

Weight-loss treatments that are tailored to the individual.....................................................................6

Social prescription by the state...............................................................................................................6

Surgical procedures.................................................................................................................................7

Reducing health disparities.....................................................................................................................7

Approaches to community health improvement that are holistic in nature...........................................7

C. Statistical data.....................................................................................................................................8

References.................................................................................................................................................10

1

Contents

A. The Epidemiology of Obesity...............................................................................................................2

B. Determinants of Health.......................................................................................................................5

Understanding the causes of obesity......................................................................................................5

Obesity risk factors and who is most affected by them...........................................................................5

Diet and food environment.....................................................................................................................5

Physical exercise......................................................................................................................................5

Obesity policy and strategy currently in place.........................................................................................5

Supporting change in behaviour..............................................................................................................6

Interventions based on opportunities.....................................................................................................6

Weight-loss treatments that are tailored to the individual.....................................................................6

Social prescription by the state...............................................................................................................6

Surgical procedures.................................................................................................................................7

Reducing health disparities.....................................................................................................................7

Approaches to community health improvement that are holistic in nature...........................................7

C. Statistical data.....................................................................................................................................8

References.................................................................................................................................................10

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A. The Epidemiology of Obesity

Obesity has been defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 1998) as "a BMI of 30 kg/m2" and

declared an epidemic. According to Finucane et al. (2011), obesity has impacted globally since the

1980s, to the extent that it is now acknowledged as a global pandemic. Obesity increases the risk of

various illnesses and ailments linked with an increased risk of death. Obesity can associate with other

health conditions, which may include “Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular diseases (CVD),

metabolic syndrome (MetS). It also includes chronic kidney disease (CKD), hyperlipidemia, hypertension,

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), certain cancers, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and

depression” (Swinburn et al., 2011, p. 564). Treating these disorders can put additional strain on

healthcare systems: for example, obese people are projected to have a 30% greater medical expenditure

than those with a normal BMI (WHO, 2000). Dealing with the implications of obesity is an expensive

problem for patients since linked overall healthcare expenses undergo an increase every decade (Bray et

al., 2017).

Several different processes can cause obesity. The conventional wisdom holds that the primary reason is

much more surplus energy saved than the energy needed by the body. Surplus energy is deposited in

“fat cells”, resulting in the typical obesity pathophysiology. The abnormal expansion of “fat cells” will

change the nutritional signals that cause obesity (Lee & Shin, 2009). However, Sacks et al.’s (2009) study

has shown that the quality and quantity of nutrients in the diet are more important than their quantity

for controlling weight and preventing illness. Gradually more etiologies or disorders that contribute to

obesity are being uncovered against the backdrop of “a battle between nurture and nature, genetic and

epigenetic, environmental and micro-environmental factors” (Dubern,. 2019, p. 1017). Genetic variables

are discerned to play essential roles in influencing an individual's proclivity to acquire weight (Singh et

al., 2017). Epigenetic research carried out by Lopomo et al. (2016) has offered essential tools for

studying the global obesity epidemic. Studies on the links “between genetics, epigenetics, and

environment in obesity” have been conducted, and “the roles of epigenetic variables” in metabolic

control, obesity risk, and its comorbidities have been investigated (Dubern, 2019, p. 1017).

The National Health Service (NHS) Digital (2020) data shows that in 2019 64% of adults were overweight

in England, among whom 28% were obese and 3% were severely obese. It has been evaluated that after

continual growth in 1990, overweight categories of overall proportion were relatively high. But steady,

at little more than 60% between 2000 and 2019. This general stability conceals some “troubling

2

Obesity has been defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 1998) as "a BMI of 30 kg/m2" and

declared an epidemic. According to Finucane et al. (2011), obesity has impacted globally since the

1980s, to the extent that it is now acknowledged as a global pandemic. Obesity increases the risk of

various illnesses and ailments linked with an increased risk of death. Obesity can associate with other

health conditions, which may include “Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular diseases (CVD),

metabolic syndrome (MetS). It also includes chronic kidney disease (CKD), hyperlipidemia, hypertension,

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), certain cancers, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and

depression” (Swinburn et al., 2011, p. 564). Treating these disorders can put additional strain on

healthcare systems: for example, obese people are projected to have a 30% greater medical expenditure

than those with a normal BMI (WHO, 2000). Dealing with the implications of obesity is an expensive

problem for patients since linked overall healthcare expenses undergo an increase every decade (Bray et

al., 2017).

Several different processes can cause obesity. The conventional wisdom holds that the primary reason is

much more surplus energy saved than the energy needed by the body. Surplus energy is deposited in

“fat cells”, resulting in the typical obesity pathophysiology. The abnormal expansion of “fat cells” will

change the nutritional signals that cause obesity (Lee & Shin, 2009). However, Sacks et al.’s (2009) study

has shown that the quality and quantity of nutrients in the diet are more important than their quantity

for controlling weight and preventing illness. Gradually more etiologies or disorders that contribute to

obesity are being uncovered against the backdrop of “a battle between nurture and nature, genetic and

epigenetic, environmental and micro-environmental factors” (Dubern,. 2019, p. 1017). Genetic variables

are discerned to play essential roles in influencing an individual's proclivity to acquire weight (Singh et

al., 2017). Epigenetic research carried out by Lopomo et al. (2016) has offered essential tools for

studying the global obesity epidemic. Studies on the links “between genetics, epigenetics, and

environment in obesity” have been conducted, and “the roles of epigenetic variables” in metabolic

control, obesity risk, and its comorbidities have been investigated (Dubern, 2019, p. 1017).

The National Health Service (NHS) Digital (2020) data shows that in 2019 64% of adults were overweight

in England, among whom 28% were obese and 3% were severely obese. It has been evaluated that after

continual growth in 1990, overweight categories of overall proportion were relatively high. But steady,

at little more than 60% between 2000 and 2019. This general stability conceals some “troubling

2

underlying trends, as obesity and morbid obesity” rates have grown “in absolute terms and as a

proportion” of all people who are overweight (Holmes, 2021, p. 4). According to the “City of

Wolverhampton Council’s Public Health Annual Report 2018-2019: Health in the City of

Wolverhampton”, the council plans to “develop a strategic, system-wide response across the city to

ensure children and young people can grow healthily. Work with West Midlands Combined Authority on

progressing the regional focus on obesity prevention, to support us in our Healthy Growth agenda” (p.

12). Moreover, it has been noted in the “City of Wolverhampton Council’s Public Health Annual Report

2020-21 from Covid-19. There is a response, Protect and Relight” that “Being overweight or obese puts

you at greater risk of serious illness or death from Covid-19, as well as from many other life-threatening

diseases” (p. 12). According to the report, “67.4% of adults over 18 in Wolverhampton are classified as

overweight or obese” (p. 12). Further stressing the need, role and importance of green spaces in the

city, the report states: “The benefits of spending time outside are widely recognized, with access to

green spaces, including trees and woodland, proven to improve both our physical and mental wellbeing.

Access to green spaces can encourage physical activity and help reduce obesity, relieve stress,

encourage social interaction and improve quality of life. It brings about cost savings to the NHS as well

as wider economic benefits, through a healthier, more active population” (p. 42).

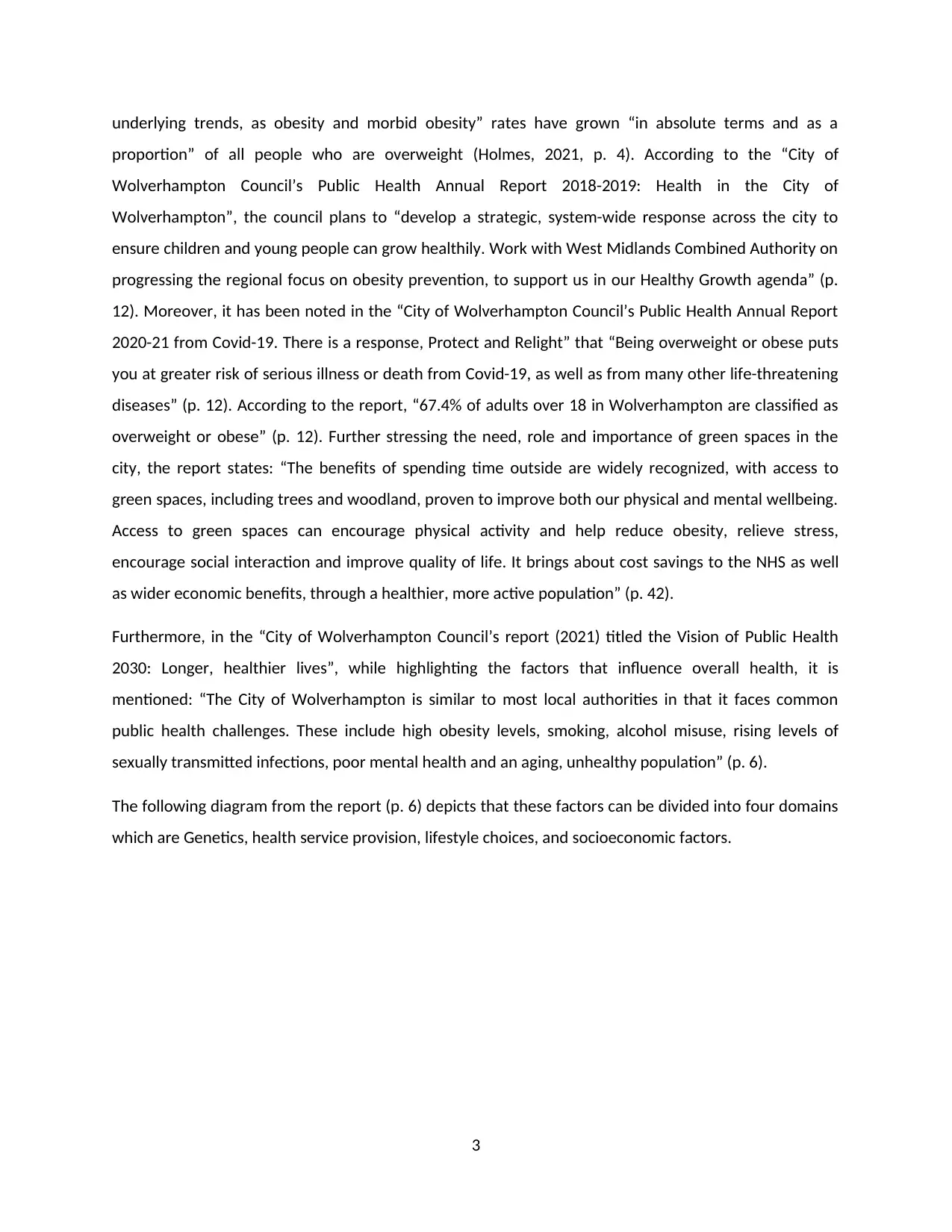

Furthermore, in the “City of Wolverhampton Council’s report (2021) titled the Vision of Public Health

2030: Longer, healthier lives”, while highlighting the factors that influence overall health, it is

mentioned: “The City of Wolverhampton is similar to most local authorities in that it faces common

public health challenges. These include high obesity levels, smoking, alcohol misuse, rising levels of

sexually transmitted infections, poor mental health and an aging, unhealthy population” (p. 6).

The following diagram from the report (p. 6) depicts that these factors can be divided into four domains

which are Genetics, health service provision, lifestyle choices, and socioeconomic factors.

3

proportion” of all people who are overweight (Holmes, 2021, p. 4). According to the “City of

Wolverhampton Council’s Public Health Annual Report 2018-2019: Health in the City of

Wolverhampton”, the council plans to “develop a strategic, system-wide response across the city to

ensure children and young people can grow healthily. Work with West Midlands Combined Authority on

progressing the regional focus on obesity prevention, to support us in our Healthy Growth agenda” (p.

12). Moreover, it has been noted in the “City of Wolverhampton Council’s Public Health Annual Report

2020-21 from Covid-19. There is a response, Protect and Relight” that “Being overweight or obese puts

you at greater risk of serious illness or death from Covid-19, as well as from many other life-threatening

diseases” (p. 12). According to the report, “67.4% of adults over 18 in Wolverhampton are classified as

overweight or obese” (p. 12). Further stressing the need, role and importance of green spaces in the

city, the report states: “The benefits of spending time outside are widely recognized, with access to

green spaces, including trees and woodland, proven to improve both our physical and mental wellbeing.

Access to green spaces can encourage physical activity and help reduce obesity, relieve stress,

encourage social interaction and improve quality of life. It brings about cost savings to the NHS as well

as wider economic benefits, through a healthier, more active population” (p. 42).

Furthermore, in the “City of Wolverhampton Council’s report (2021) titled the Vision of Public Health

2030: Longer, healthier lives”, while highlighting the factors that influence overall health, it is

mentioned: “The City of Wolverhampton is similar to most local authorities in that it faces common

public health challenges. These include high obesity levels, smoking, alcohol misuse, rising levels of

sexually transmitted infections, poor mental health and an aging, unhealthy population” (p. 6).

The following diagram from the report (p. 6) depicts that these factors can be divided into four domains

which are Genetics, health service provision, lifestyle choices, and socioeconomic factors.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Moreover, the report notes that the prevalence of childhood obesity (of children at the age of year 6) in

the city is 26.7% were “upward trend is continuing to increase” and is “higher than England average of

20%”, whereas that among adults is “28.5% which is higher than England average of 24.4%” (p. 7).

Obesity is widely referred to as an epidemic in the literature (WHO, 2000; Roth et al., 2004) because

obesity has grown fast, reaching record-high proportions. An epidemic’s progression is best defined by a

wave pattern, with an initial spike “followed by a plateau and then a fall” (Roth et al., 2004, p. 89S). This

approach has recently been employed on the obesity pandemic (Xu & Lam, 2018). However, it has still

to be adequately researched. The obesity epidemic is anticipated to continue to pose significant dangers

to public health as younger generations are subjected to circumstances that are “even more obesogenic

than those experienced by earlier generations” (Reither et al., 2009, p. 1440).

Since 1980, the incidence of excessive weight gain has more than quadrupled globally, and almost one-

third of the world population is either overweight or obese (Ataey, 2020). Obesity rates have

skyrocketed in men and women of all ages, with older people and women bearing a disproportionately

more enormous burden (WHO, 1998). While this is a global trend, absolute incidence rates vary by

location, country, and ethnicity. Obesity prevalence also varies by socioeconomic class, with higher-

income and certain middle-income nations experiencing slower rates of BMI growth. Obesity was

formerly thought to be a problem faced by high-income nations. However, “the incidence rates of obese

or overweight children in high-income countries such as the United States, Sweden, Denmark, Norway,

France, Australia, and Japan have fallen or plateaued since the early 2000s” (NCD-RisC, 2017, p. 2628).

It should not be forgotten that obese persons are less likely to work professionally because of

comorbidities, and children perform worse in school. Unwanted weight gain is produced by a positive

energy balance, which means that a person consumes more calories than they ought to consume. The

4

the city is 26.7% were “upward trend is continuing to increase” and is “higher than England average of

20%”, whereas that among adults is “28.5% which is higher than England average of 24.4%” (p. 7).

Obesity is widely referred to as an epidemic in the literature (WHO, 2000; Roth et al., 2004) because

obesity has grown fast, reaching record-high proportions. An epidemic’s progression is best defined by a

wave pattern, with an initial spike “followed by a plateau and then a fall” (Roth et al., 2004, p. 89S). This

approach has recently been employed on the obesity pandemic (Xu & Lam, 2018). However, it has still

to be adequately researched. The obesity epidemic is anticipated to continue to pose significant dangers

to public health as younger generations are subjected to circumstances that are “even more obesogenic

than those experienced by earlier generations” (Reither et al., 2009, p. 1440).

Since 1980, the incidence of excessive weight gain has more than quadrupled globally, and almost one-

third of the world population is either overweight or obese (Ataey, 2020). Obesity rates have

skyrocketed in men and women of all ages, with older people and women bearing a disproportionately

more enormous burden (WHO, 1998). While this is a global trend, absolute incidence rates vary by

location, country, and ethnicity. Obesity prevalence also varies by socioeconomic class, with higher-

income and certain middle-income nations experiencing slower rates of BMI growth. Obesity was

formerly thought to be a problem faced by high-income nations. However, “the incidence rates of obese

or overweight children in high-income countries such as the United States, Sweden, Denmark, Norway,

France, Australia, and Japan have fallen or plateaued since the early 2000s” (NCD-RisC, 2017, p. 2628).

It should not be forgotten that obese persons are less likely to work professionally because of

comorbidities, and children perform worse in school. Unwanted weight gain is produced by a positive

energy balance, which means that a person consumes more calories than they ought to consume. The

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

obesity epidemic’s causes are complicated. Many of these are referred to as the “Environment

Favorable to Obesity” and include elements such as societal structure, economic policy, socio-economic

development (a higher number of urban inhabitants, driving vehicles, a sedentary lifestyle at home and

at work, consumption of processed food, and so on) (Olszewska et al., 2018, p. 103).

B. Determinants of Health

Understanding the causes of obesity

Before looking into the determinants of health, it is essential to understand the causes of obesity and

the risk factors associated with this condition.

Obesity risk factors and who is most affected by them

Excess weight gain happens when an individual consumes more food than required regularly. There is an

accumulation of fat due to consuming access calories that are not being utilized and transformed into

fat. Consequently, the scientific consensus is essential to consume fewer calories for weight loss, but

physical exercise holds equal importance to maintaining a healthy weight (Westerterp 2019; Cox 2017).

Diet and food environment

Everyone faces many hurdles and problems in keeping a healthy diet, but people living in England’s most

underprivileged areas are facing these problems the most intensely (Marmot et al., 2020). The setting in

which individuals live might be presenting them with one of the most challenging obstacles to eating

correctly. In this regard, it has been evidenced that unhealthy food environments are more common in

poorer communities in England (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019).

Physical exercise

Although physical exercise is secondary to diet about obesity causes, it can help lose weight and stay

healthy. Population in less affluent areas of England register “lower levels of physical activity “compared

to the national average. In the most impoverished neighborhoods, 62% of adults report being

“physically active, compared to a national average of 66%” (Public Health England, 2021, n.p.).

Obesity policy and strategy currently in place

To respond to growing rates of obesity, contemporary governments in England have developed a variety

of tactics and policies to halt the trend of obesity (Theis & White, 2021). The governments have

5

Favorable to Obesity” and include elements such as societal structure, economic policy, socio-economic

development (a higher number of urban inhabitants, driving vehicles, a sedentary lifestyle at home and

at work, consumption of processed food, and so on) (Olszewska et al., 2018, p. 103).

B. Determinants of Health

Understanding the causes of obesity

Before looking into the determinants of health, it is essential to understand the causes of obesity and

the risk factors associated with this condition.

Obesity risk factors and who is most affected by them

Excess weight gain happens when an individual consumes more food than required regularly. There is an

accumulation of fat due to consuming access calories that are not being utilized and transformed into

fat. Consequently, the scientific consensus is essential to consume fewer calories for weight loss, but

physical exercise holds equal importance to maintaining a healthy weight (Westerterp 2019; Cox 2017).

Diet and food environment

Everyone faces many hurdles and problems in keeping a healthy diet, but people living in England’s most

underprivileged areas are facing these problems the most intensely (Marmot et al., 2020). The setting in

which individuals live might be presenting them with one of the most challenging obstacles to eating

correctly. In this regard, it has been evidenced that unhealthy food environments are more common in

poorer communities in England (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2019).

Physical exercise

Although physical exercise is secondary to diet about obesity causes, it can help lose weight and stay

healthy. Population in less affluent areas of England register “lower levels of physical activity “compared

to the national average. In the most impoverished neighborhoods, 62% of adults report being

“physically active, compared to a national average of 66%” (Public Health England, 2021, n.p.).

Obesity policy and strategy currently in place

To respond to growing rates of obesity, contemporary governments in England have developed a variety

of tactics and policies to halt the trend of obesity (Theis & White, 2021). The governments have

5

dispersed these plans throughout numerous policy papers, and responsibility for carrying them out is

shared among multiple government organizations and departments (Holmes, 2021)

Supporting change in behavior

The two most important “behavioral risk factors” for obesity are diet and physical inactivity. It is possible

to address these by working with obese individuals to modify sedentary behaviors. However, an

individual's surroundings and socioeconomic situations have a substantial impact on their choices. They

can be a major obstacle to long-term behaviour change, especially in disadvantaged areas regions. The

NHS may help encourage behavior change “by providing information, clinical treatments, and service

design”, for example, “opportunistic interventions, targeted weight management programs, social

prescribing, and surgical procedures” (Holmes, 2021, p. 7).

Interventions based on opportunities

Studies have proved that most people are open to receiving health advice from a reputable health

expert, as noted by Albury et al. (2018). However, studies have also evidenced that various health

professionals are genuinely uncomfortable or afraid to discuss obesity with such patients (Wynn et al.,

2018). There is the need to increase health care workers' expertise and confidence when it comes to

discuss nutrition, and urges for nutrition awareness and teach this as a core module within medical

schools (Holmes, 2021). It has been emphasized by “the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England 2019)”.

Weight-loss treatments that are tailored to the individual

Weight management services include “a wide variety of health advice, information, and behavior change

assistance” ordered and delivered by local governments and clinical commissioning groups of the NHS.

Studies have evidenced that these can prove to be a beneficial intervention to enhance long-term

improvement in the health of the country’s population (Valabhji et al., 2020),

Social prescription by the state

Social prescribing allows health practitioners to refer their obese clients to various non-clinical

therapies. Buck and Ewbank (2020) posit that referrals are typically, however not always, made by

professionals working in primary care settings, such as general practitioners or practice nurses. A variety

of physical activities fall under social prescribing. These physical activities are often arranged and offered

by non-profit and community-based organizations in England. It might comprise behavior modification

assistance. For example- healthy eating advice, cooking lessons, or physical activities such as sports or

6

shared among multiple government organizations and departments (Holmes, 2021)

Supporting change in behavior

The two most important “behavioral risk factors” for obesity are diet and physical inactivity. It is possible

to address these by working with obese individuals to modify sedentary behaviors. However, an

individual's surroundings and socioeconomic situations have a substantial impact on their choices. They

can be a major obstacle to long-term behaviour change, especially in disadvantaged areas regions. The

NHS may help encourage behavior change “by providing information, clinical treatments, and service

design”, for example, “opportunistic interventions, targeted weight management programs, social

prescribing, and surgical procedures” (Holmes, 2021, p. 7).

Interventions based on opportunities

Studies have proved that most people are open to receiving health advice from a reputable health

expert, as noted by Albury et al. (2018). However, studies have also evidenced that various health

professionals are genuinely uncomfortable or afraid to discuss obesity with such patients (Wynn et al.,

2018). There is the need to increase health care workers' expertise and confidence when it comes to

discuss nutrition, and urges for nutrition awareness and teach this as a core module within medical

schools (Holmes, 2021). It has been emphasized by “the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England 2019)”.

Weight-loss treatments that are tailored to the individual

Weight management services include “a wide variety of health advice, information, and behavior change

assistance” ordered and delivered by local governments and clinical commissioning groups of the NHS.

Studies have evidenced that these can prove to be a beneficial intervention to enhance long-term

improvement in the health of the country’s population (Valabhji et al., 2020),

Social prescription by the state

Social prescribing allows health practitioners to refer their obese clients to various non-clinical

therapies. Buck and Ewbank (2020) posit that referrals are typically, however not always, made by

professionals working in primary care settings, such as general practitioners or practice nurses. A variety

of physical activities fall under social prescribing. These physical activities are often arranged and offered

by non-profit and community-based organizations in England. It might comprise behavior modification

assistance. For example- healthy eating advice, cooking lessons, or physical activities such as sports or

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

walking groups, however social prescribing as a paradigm holds a holistic approach to physical and

mental welfare (Holmes, 2021).

Surgical procedures

Weight-loss surgery, commonly known as “bariatric surgery”, may lead to a considerable weight

reduction and relieve obesity-related diseases (NHS, n.d.).

Reducing health disparities

The “NHS planning advice for 2021/22 (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021)” reaffirms the

importance of addressing health disparities. It returns to the “NHS Long Term Plan” priorities. It

necessitates systems to designate a senior accountable person to establish strategies to promote

primary and secondary illness prevention and minimize health inequities. The recommendation states

unequivocally that “these plans should include initiatives to prevent and manage obesity, with a focus

on the populations most impacted by obesity and experiencing some of the poorest health outcomes as

a result”. It covers the most disadvantaged communities, notably “women, as well as some ethnic

minority groups” (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2019b, n.p.).

Approaches to community health improvement that are holistic

Local authorities within England are working in close collaboration with their communities to improve

health outcomes, particularly tackling the obesity risk factors linked with lifestyle (Local Government

Association, 2019). Several localities have put “systemic obesity strategies” into practice through “health

and wellbeing boards”. NHS provides holistic approaches and a variety of the above-mentioned

interventions such as “supporting behavior change, acting as an anchor institution, and providing system

leadership”. During collaboration with local governments and community groups, it can ensure that

“interventions is a part of a holistic health improvement,” which helps in addressing “all four pillars of

population health” (Holmes, 2021, p. 8). There are some determinants of health, health behavior and

lifestyles. It also includes an integrated health and care system and the places and communities we live

in, and with” (The King’s Fund, 2021, pp. 4-5).

C. Statistical data

The study hypothesizes that South Asian patients with diabetes have significantly higher BMI than non-

South Asians with diabetes. The study was Wolverhampton. The population for the study consisted of

7

mental welfare (Holmes, 2021).

Surgical procedures

Weight-loss surgery, commonly known as “bariatric surgery”, may lead to a considerable weight

reduction and relieve obesity-related diseases (NHS, n.d.).

Reducing health disparities

The “NHS planning advice for 2021/22 (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021)” reaffirms the

importance of addressing health disparities. It returns to the “NHS Long Term Plan” priorities. It

necessitates systems to designate a senior accountable person to establish strategies to promote

primary and secondary illness prevention and minimize health inequities. The recommendation states

unequivocally that “these plans should include initiatives to prevent and manage obesity, with a focus

on the populations most impacted by obesity and experiencing some of the poorest health outcomes as

a result”. It covers the most disadvantaged communities, notably “women, as well as some ethnic

minority groups” (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2019b, n.p.).

Approaches to community health improvement that are holistic

Local authorities within England are working in close collaboration with their communities to improve

health outcomes, particularly tackling the obesity risk factors linked with lifestyle (Local Government

Association, 2019). Several localities have put “systemic obesity strategies” into practice through “health

and wellbeing boards”. NHS provides holistic approaches and a variety of the above-mentioned

interventions such as “supporting behavior change, acting as an anchor institution, and providing system

leadership”. During collaboration with local governments and community groups, it can ensure that

“interventions is a part of a holistic health improvement,” which helps in addressing “all four pillars of

population health” (Holmes, 2021, p. 8). There are some determinants of health, health behavior and

lifestyles. It also includes an integrated health and care system and the places and communities we live

in, and with” (The King’s Fund, 2021, pp. 4-5).

C. Statistical data

The study hypothesizes that South Asian patients with diabetes have significantly higher BMI than non-

South Asians with diabetes. The study was Wolverhampton. The population for the study consisted of

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

South Asian and non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes living in Wolverhampton. The data was

collected through a survey questionnaire. The data was analysed through the statistical test of

independent sample t-test which helped in testing and comparing the difference between the BMI

means of obese patients with diabetes from two independent groups that is South Asians and non-

South Asians living in Wolverhampton by means of SPSS. The independent variable is the obese

condition with diabetes and the dependent variable or the test variable is the BMI. A strength of t-test is

that it is a parametric test which is suitable for measuring the difference between two independent

groups as was the case in this study. However, in the case of the current study, a limitation was noticed

in the form of unbalanced sample size where the first group sample was smaller (N = 152) compared to

the second group (N = 448) which could impact the final results and findings. Population distributions

that are non-normal, specifically those that are heavily skewed or thick-tailed as in the case of non-

South Asian sample in the current study, lead to a considerable reduction in the test’s power. One of the

key requirements of t-test is to have a balanced design that is same sample size or number of

participants in each sample group. Highly imbalanced designs raise the likelihood that breaching any of

the requirements or assumptions may jeopardise the independent samples t-test validity. When this

assumption is broken and the sample sizes for each of the study group change, the p value is no longer

reliable. However, the result of the independent samples t-test contains an approximation t statistic that

is not based on assuming equal population variances, which was not considered in the current study.

Another limitation is that it is not known if the sample for both the groups was randomly selected from

the population (residents of Wolverhampton). Random sample is a pre-requisite of t-test.

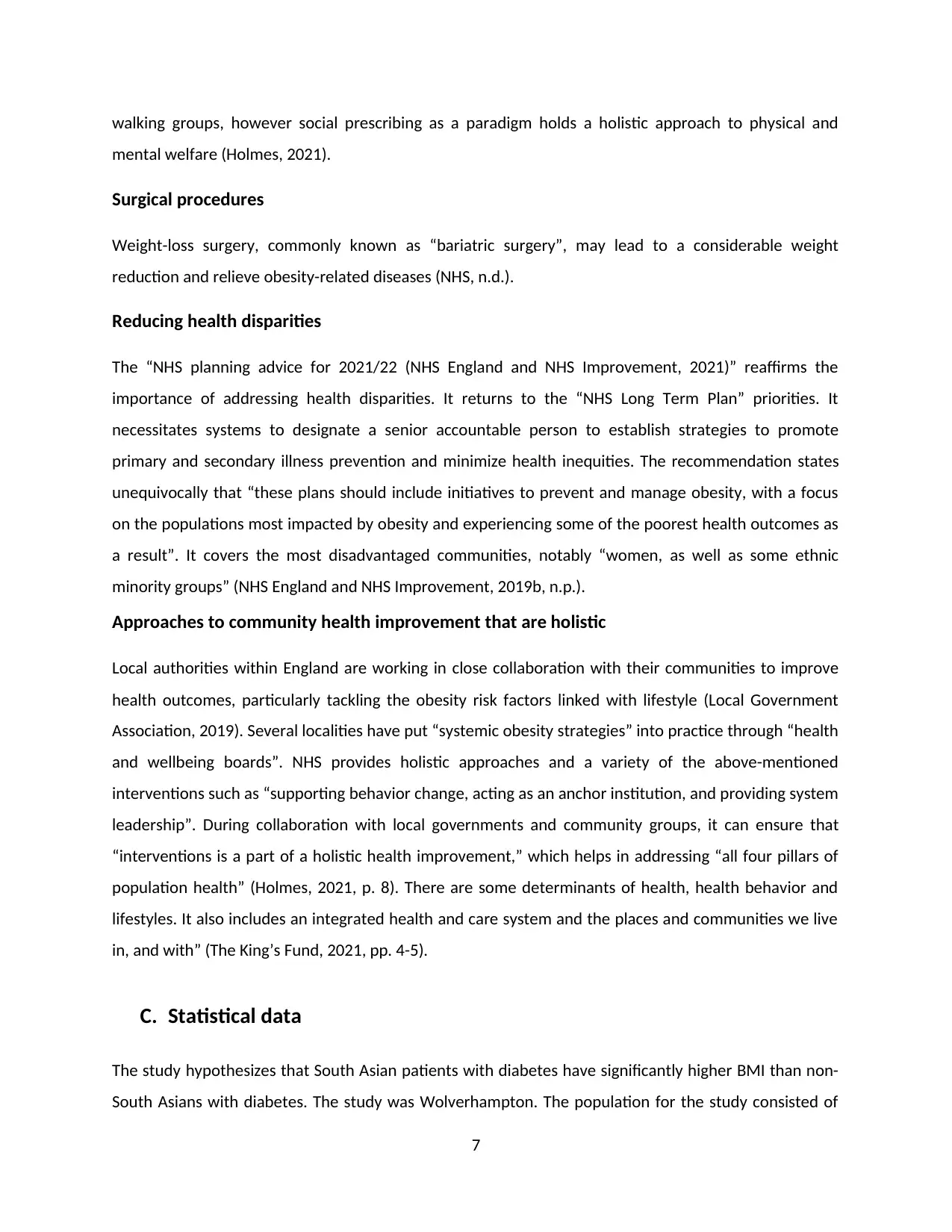

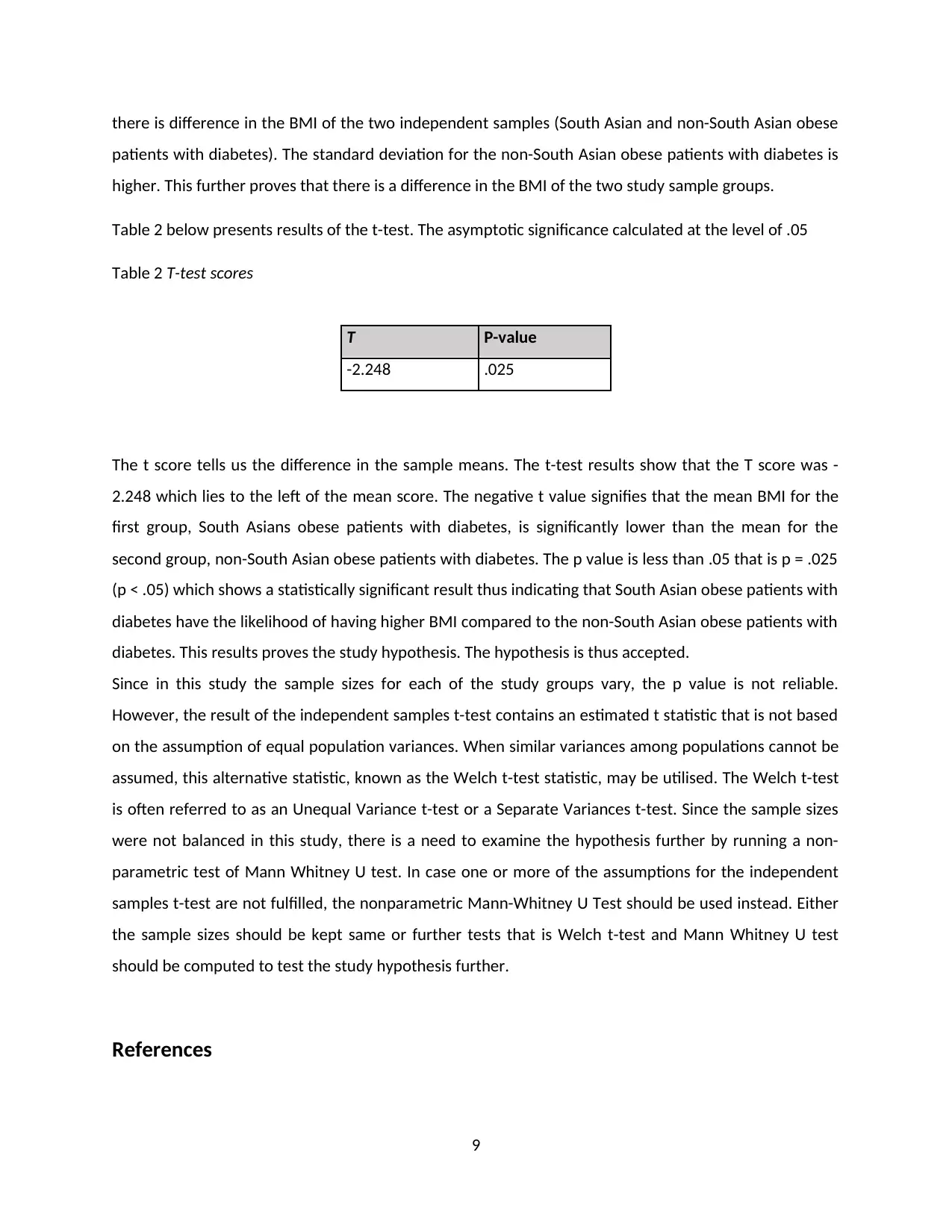

Table 1 presents the scores of sample groups, sample size, Mean BMI and Standard Deviation.

Table 1

South Asian Sample Size Mean BMI Std. Deviation

Body Mass Index Yes 152 27.26 4.779

No 448 28.34 5.232

The data in the table above shows that the total sample size was 600 out of whom 152 were South

Asians and 448 were non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes. The mean BMI of the South Asians

was M = 27.26 and that of non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes was M = 28.34. The mean BMI

of non-South Asians was a little higher than that of the South Asian obese patients. This indicates that

8

collected through a survey questionnaire. The data was analysed through the statistical test of

independent sample t-test which helped in testing and comparing the difference between the BMI

means of obese patients with diabetes from two independent groups that is South Asians and non-

South Asians living in Wolverhampton by means of SPSS. The independent variable is the obese

condition with diabetes and the dependent variable or the test variable is the BMI. A strength of t-test is

that it is a parametric test which is suitable for measuring the difference between two independent

groups as was the case in this study. However, in the case of the current study, a limitation was noticed

in the form of unbalanced sample size where the first group sample was smaller (N = 152) compared to

the second group (N = 448) which could impact the final results and findings. Population distributions

that are non-normal, specifically those that are heavily skewed or thick-tailed as in the case of non-

South Asian sample in the current study, lead to a considerable reduction in the test’s power. One of the

key requirements of t-test is to have a balanced design that is same sample size or number of

participants in each sample group. Highly imbalanced designs raise the likelihood that breaching any of

the requirements or assumptions may jeopardise the independent samples t-test validity. When this

assumption is broken and the sample sizes for each of the study group change, the p value is no longer

reliable. However, the result of the independent samples t-test contains an approximation t statistic that

is not based on assuming equal population variances, which was not considered in the current study.

Another limitation is that it is not known if the sample for both the groups was randomly selected from

the population (residents of Wolverhampton). Random sample is a pre-requisite of t-test.

Table 1 presents the scores of sample groups, sample size, Mean BMI and Standard Deviation.

Table 1

South Asian Sample Size Mean BMI Std. Deviation

Body Mass Index Yes 152 27.26 4.779

No 448 28.34 5.232

The data in the table above shows that the total sample size was 600 out of whom 152 were South

Asians and 448 were non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes. The mean BMI of the South Asians

was M = 27.26 and that of non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes was M = 28.34. The mean BMI

of non-South Asians was a little higher than that of the South Asian obese patients. This indicates that

8

there is difference in the BMI of the two independent samples (South Asian and non-South Asian obese

patients with diabetes). The standard deviation for the non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes is

higher. This further proves that there is a difference in the BMI of the two study sample groups.

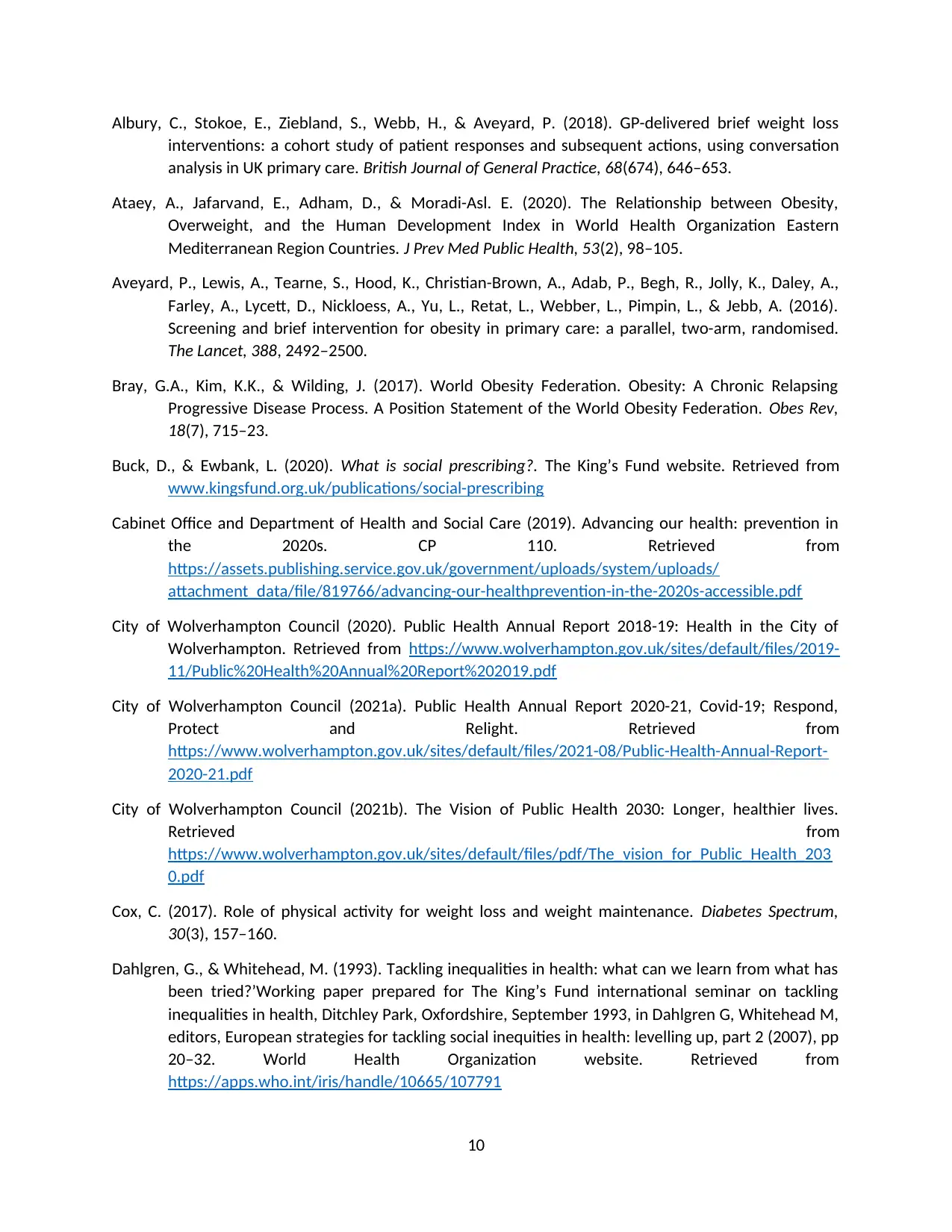

Table 2 below presents results of the t-test. The asymptotic significance calculated at the level of .05

Table 2 T-test scores

T P-value

-2.248 .025

The t score tells us the difference in the sample means. The t-test results show that the T score was -

2.248 which lies to the left of the mean score. The negative t value signifies that the mean BMI for the

first group, South Asians obese patients with diabetes, is significantly lower than the mean for the

second group, non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes. The p value is less than .05 that is p = .025

(p < .05) which shows a statistically significant result thus indicating that South Asian obese patients with

diabetes have the likelihood of having higher BMI compared to the non-South Asian obese patients with

diabetes. This results proves the study hypothesis. The hypothesis is thus accepted.

Since in this study the sample sizes for each of the study groups vary, the p value is not reliable.

However, the result of the independent samples t-test contains an estimated t statistic that is not based

on the assumption of equal population variances. When similar variances among populations cannot be

assumed, this alternative statistic, known as the Welch t-test statistic, may be utilised. The Welch t-test

is often referred to as an Unequal Variance t-test or a Separate Variances t-test. Since the sample sizes

were not balanced in this study, there is a need to examine the hypothesis further by running a non-

parametric test of Mann Whitney U test. In case one or more of the assumptions for the independent

samples t-test are not fulfilled, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U Test should be used instead. Either

the sample sizes should be kept same or further tests that is Welch t-test and Mann Whitney U test

should be computed to test the study hypothesis further.

References

9

patients with diabetes). The standard deviation for the non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes is

higher. This further proves that there is a difference in the BMI of the two study sample groups.

Table 2 below presents results of the t-test. The asymptotic significance calculated at the level of .05

Table 2 T-test scores

T P-value

-2.248 .025

The t score tells us the difference in the sample means. The t-test results show that the T score was -

2.248 which lies to the left of the mean score. The negative t value signifies that the mean BMI for the

first group, South Asians obese patients with diabetes, is significantly lower than the mean for the

second group, non-South Asian obese patients with diabetes. The p value is less than .05 that is p = .025

(p < .05) which shows a statistically significant result thus indicating that South Asian obese patients with

diabetes have the likelihood of having higher BMI compared to the non-South Asian obese patients with

diabetes. This results proves the study hypothesis. The hypothesis is thus accepted.

Since in this study the sample sizes for each of the study groups vary, the p value is not reliable.

However, the result of the independent samples t-test contains an estimated t statistic that is not based

on the assumption of equal population variances. When similar variances among populations cannot be

assumed, this alternative statistic, known as the Welch t-test statistic, may be utilised. The Welch t-test

is often referred to as an Unequal Variance t-test or a Separate Variances t-test. Since the sample sizes

were not balanced in this study, there is a need to examine the hypothesis further by running a non-

parametric test of Mann Whitney U test. In case one or more of the assumptions for the independent

samples t-test are not fulfilled, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U Test should be used instead. Either

the sample sizes should be kept same or further tests that is Welch t-test and Mann Whitney U test

should be computed to test the study hypothesis further.

References

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Albury, C., Stokoe, E., Ziebland, S., Webb, H., & Aveyard, P. (2018). GP-delivered brief weight loss

interventions: a cohort study of patient responses and subsequent actions, using conversation

analysis in UK primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 68(674), 646–653.

Ataey, A., Jafarvand, E., Adham, D., & Moradi-Asl. E. (2020). The Relationship between Obesity,

Overweight, and the Human Development Index in World Health Organization Eastern

Mediterranean Region Countries. J Prev Med Public Health, 53(2), 98–105.

Aveyard, P., Lewis, A., Tearne, S., Hood, K., Christian-Brown, A., Adab, P., Begh, R., Jolly, K., Daley, A.,

Farley, A., Lycett, D., Nickloess, A., Yu, L., Retat, L., Webber, L., Pimpin, L., & Jebb, A. (2016).

Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised.

The Lancet, 388, 2492–2500.

Bray, G.A., Kim, K.K., & Wilding, J. (2017). World Obesity Federation. Obesity: A Chronic Relapsing

Progressive Disease Process. A Position Statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev,

18(7), 715–23.

Buck, D., & Ewbank, L. (2020). What is social prescribing?. The King’s Fund website. Retrieved from

www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing

Cabinet Office and Department of Health and Social Care (2019). Advancing our health: prevention in

the 2020s. CP 110. Retrieved from

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/819766/advancing-our-healthprevention-in-the-2020s-accessible.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2020). Public Health Annual Report 2018-19: Health in the City of

Wolverhampton. Retrieved from https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2019-

11/Public%20Health%20Annual%20Report%202019.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2021a). Public Health Annual Report 2020-21, Covid-19; Respond,

Protect and Relight. Retrieved from

https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2021-08/Public-Health-Annual-Report-

2020-21.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2021b). The Vision of Public Health 2030: Longer, healthier lives.

Retrieved from

https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/The_vision_for_Public_Health_203

0.pdf

Cox, C. (2017). Role of physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. Diabetes Spectrum,

30(3), 157–160.

Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1993). Tackling inequalities in health: what can we learn from what has

been tried?’Working paper prepared for The King’s Fund international seminar on tackling

inequalities in health, Ditchley Park, Oxfordshire, September 1993, in Dahlgren G, Whitehead M,

editors, European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up, part 2 (2007), pp

20–32. World Health Organization website. Retrieved from

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107791

10

interventions: a cohort study of patient responses and subsequent actions, using conversation

analysis in UK primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 68(674), 646–653.

Ataey, A., Jafarvand, E., Adham, D., & Moradi-Asl. E. (2020). The Relationship between Obesity,

Overweight, and the Human Development Index in World Health Organization Eastern

Mediterranean Region Countries. J Prev Med Public Health, 53(2), 98–105.

Aveyard, P., Lewis, A., Tearne, S., Hood, K., Christian-Brown, A., Adab, P., Begh, R., Jolly, K., Daley, A.,

Farley, A., Lycett, D., Nickloess, A., Yu, L., Retat, L., Webber, L., Pimpin, L., & Jebb, A. (2016).

Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised.

The Lancet, 388, 2492–2500.

Bray, G.A., Kim, K.K., & Wilding, J. (2017). World Obesity Federation. Obesity: A Chronic Relapsing

Progressive Disease Process. A Position Statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev,

18(7), 715–23.

Buck, D., & Ewbank, L. (2020). What is social prescribing?. The King’s Fund website. Retrieved from

www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing

Cabinet Office and Department of Health and Social Care (2019). Advancing our health: prevention in

the 2020s. CP 110. Retrieved from

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/819766/advancing-our-healthprevention-in-the-2020s-accessible.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2020). Public Health Annual Report 2018-19: Health in the City of

Wolverhampton. Retrieved from https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2019-

11/Public%20Health%20Annual%20Report%202019.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2021a). Public Health Annual Report 2020-21, Covid-19; Respond,

Protect and Relight. Retrieved from

https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2021-08/Public-Health-Annual-Report-

2020-21.pdf

City of Wolverhampton Council (2021b). The Vision of Public Health 2030: Longer, healthier lives.

Retrieved from

https://www.wolverhampton.gov.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/The_vision_for_Public_Health_203

0.pdf

Cox, C. (2017). Role of physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. Diabetes Spectrum,

30(3), 157–160.

Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1993). Tackling inequalities in health: what can we learn from what has

been tried?’Working paper prepared for The King’s Fund international seminar on tackling

inequalities in health, Ditchley Park, Oxfordshire, September 1993, in Dahlgren G, Whitehead M,

editors, European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up, part 2 (2007), pp

20–32. World Health Organization website. Retrieved from

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107791

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Department of Health and Social Care (2021). ‘New specialised support to help those living with obesity

to lose weight’. Press release. GOV.UK website. Retrieved from

www.gov.uk/government/news/new-specialised-support-to-help-those-living-with-obesity-to-

lose-weight

Dubern, B. (2019). Genetics and Epigenetics of Obesity: Keys to Understand. Rev Prat, 69(9), 1016–9.

Health Education England (n.d.). Making every contact count. Health Education England website.

Retrieved from www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk

Holmes, J. (2021). Tackling obesity: The role of the NHS in a whole-system approach. Retrieved from

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-07/Tackling%20obesity.pdf

Lee, S.J., & Shin, S.W. (2017). Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N Engl J Med,

376(15), 1491–2.

Local Government Association (2019). Whole systems approach to obesity: a guide to support local

approaches to achieving a healthier weight. LGA website. Retrieved from

www.local.gov.uk/publications/whole-systems-approach-obesity-guide-support-local-

approaches-achieving-healthier

Lopomo, A., Burgio, E., & Migliore, L. (2016). Epigenetics of Obesity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 140, 151–

84.

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020). Health equity in England: the

Marmot Review 10 years on. The Health Foundation website. Retrieved from

www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2019). ‘English indices of deprivation’.

GOV.UK website. Retrieved from www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-

deprivation2019

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC).Worldwide Trends in Body-Mass Index, Underweight,

Overweight, and Obesity From 1975 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 2416 Population-Based

Measurement Studies in 128·9 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Lancet (2017)

390(10113):2627–42.

NHS Digital (2020). ‘Health survey for England, 2019’. NHS Digital website. Retrieved from

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/

2019/health-survey-for-england-2019-data-tables

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2019a). Designing integrated care system (ICSs) in England. NHS

England and NHS Improvement website. Retrieved from

www.england.nhs.uk/publication/designing-integrated-care-systems-icss-in-england

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2019b). ‘Tier 2 weight management services’. NHS England and

NHS Improvement website. Retrieved from www.england.nhs.uk/ltphimenu/prevention/tier-2-

weight-management-services

11

to lose weight’. Press release. GOV.UK website. Retrieved from

www.gov.uk/government/news/new-specialised-support-to-help-those-living-with-obesity-to-

lose-weight

Dubern, B. (2019). Genetics and Epigenetics of Obesity: Keys to Understand. Rev Prat, 69(9), 1016–9.

Health Education England (n.d.). Making every contact count. Health Education England website.

Retrieved from www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk

Holmes, J. (2021). Tackling obesity: The role of the NHS in a whole-system approach. Retrieved from

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-07/Tackling%20obesity.pdf

Lee, S.J., & Shin, S.W. (2017). Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. N Engl J Med,

376(15), 1491–2.

Local Government Association (2019). Whole systems approach to obesity: a guide to support local

approaches to achieving a healthier weight. LGA website. Retrieved from

www.local.gov.uk/publications/whole-systems-approach-obesity-guide-support-local-

approaches-achieving-healthier

Lopomo, A., Burgio, E., & Migliore, L. (2016). Epigenetics of Obesity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 140, 151–

84.

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020). Health equity in England: the

Marmot Review 10 years on. The Health Foundation website. Retrieved from

www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2019). ‘English indices of deprivation’.

GOV.UK website. Retrieved from www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-

deprivation2019

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC).Worldwide Trends in Body-Mass Index, Underweight,

Overweight, and Obesity From 1975 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 2416 Population-Based

Measurement Studies in 128·9 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Lancet (2017)

390(10113):2627–42.

NHS Digital (2020). ‘Health survey for England, 2019’. NHS Digital website. Retrieved from

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/

2019/health-survey-for-england-2019-data-tables

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2019a). Designing integrated care system (ICSs) in England. NHS

England and NHS Improvement website. Retrieved from

www.england.nhs.uk/publication/designing-integrated-care-systems-icss-in-england

NHS England and NHS Improvement (2019b). ‘Tier 2 weight management services’. NHS England and

NHS Improvement website. Retrieved from www.england.nhs.uk/ltphimenu/prevention/tier-2-

weight-management-services

11

Olszewska, M., Szczerbinski, L., Siewiec, E., Puchta, U., Wojciak, P., Pawluszewicz, P., ... & Hady, H. R.

(2018). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of obesity. Post Nauk. Med, 2, 102-105.

Public Health England (2021). Public Health Outcomes Framework dashboard – percentage of physically

active adult. Public Health England website. Retrieved from

https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework/data#page/7/gid/

1000042/ati/402/iid/93014/age/298/sex/4/cid/4/tbm/1/page-options/ovw-do-0_car-ao-1_car-

do-0_ine-vo-0_ine-yo-1:2017:-1:-1_ine-ct-40_ine-pt-0

Reither, E. N., Hauser, R. M., & Yang, Y. (2009). Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of

the obesity epidemic in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 69(10), 1439-1448.

Roth, J., Qiang, X., Marban, S. L., Redelt, H., & Lowell, B. C. (2004). The obesity pandemic: Where have

we been and where are we going? Obesity Research, 12(2), 88S-101S.

Sacks, F.M., Bray, G.A., Carey, V.J., Smith, S.R., Ryan, D.H., Anton, S.D, et al. (2009). Comparison of

Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates. N Engl J Med,

360(9), 859–73.

Singh, R.K., Kumar, P., & Mahalingam, K. (2017). Molecular Genetics of Human Obesity: A

Comprehensive Review. C R Biol, 340(2), 87–108.

Swinburn, B.A., Sacks, G., Hall, K.D., McPherson, K., Finegood, D.T., Moodie, M.L., et al. (2011). The

Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. Lancet, 78(9793),

804–14.

The King’s Fund (2021). A vision for population health: Towards a healthier furure. Retrieved from

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-11/A%20vision%20for%20pop%20health

%20summary%20online%20version.pdf

Theis, D., & White, M. (2021). Is obesity policy in England fit for purpose? Analysis of government

strategies and policies, 1992–2020. The Milbank Quarterly, 99(1), 126–170.

Valabhji, J., Barron, E., Bradley, D., Bakhai, C., Fagg, J., O’Neill, S., Young, B., Wareham, N., Khunti, K., &

Jebb S, Smith, J. (2020). Early outcomes from the English National Health Service Diabetes

Prevention Programme. Diabetes Care, 43(1), 152–160.

Westerterp, K. (2019). Exercise for weight loss. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 110(3), 40–51

WHO. (1998). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation on

obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation

(Technical Report Series No. 894). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Wynn, T., Islam, N., Thompson, C., & Myint, K. (2018). The effect of knowledge on healthcare

professionals’ perceptions of obesity. Obesity Medicine, 11, 20–24.

Xu, L., & Lam, T. H. (2018). Stage of obesity epidemic model: Learning from tobacco control and

advocacy for a framework convention on obesity control. Journal of Diabetes, 10(7), 564-571.

12

(2018). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of obesity. Post Nauk. Med, 2, 102-105.

Public Health England (2021). Public Health Outcomes Framework dashboard – percentage of physically

active adult. Public Health England website. Retrieved from

https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework/data#page/7/gid/

1000042/ati/402/iid/93014/age/298/sex/4/cid/4/tbm/1/page-options/ovw-do-0_car-ao-1_car-

do-0_ine-vo-0_ine-yo-1:2017:-1:-1_ine-ct-40_ine-pt-0

Reither, E. N., Hauser, R. M., & Yang, Y. (2009). Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of

the obesity epidemic in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 69(10), 1439-1448.

Roth, J., Qiang, X., Marban, S. L., Redelt, H., & Lowell, B. C. (2004). The obesity pandemic: Where have

we been and where are we going? Obesity Research, 12(2), 88S-101S.

Sacks, F.M., Bray, G.A., Carey, V.J., Smith, S.R., Ryan, D.H., Anton, S.D, et al. (2009). Comparison of

Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates. N Engl J Med,

360(9), 859–73.

Singh, R.K., Kumar, P., & Mahalingam, K. (2017). Molecular Genetics of Human Obesity: A

Comprehensive Review. C R Biol, 340(2), 87–108.

Swinburn, B.A., Sacks, G., Hall, K.D., McPherson, K., Finegood, D.T., Moodie, M.L., et al. (2011). The

Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. Lancet, 78(9793),

804–14.

The King’s Fund (2021). A vision for population health: Towards a healthier furure. Retrieved from

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-11/A%20vision%20for%20pop%20health

%20summary%20online%20version.pdf

Theis, D., & White, M. (2021). Is obesity policy in England fit for purpose? Analysis of government

strategies and policies, 1992–2020. The Milbank Quarterly, 99(1), 126–170.

Valabhji, J., Barron, E., Bradley, D., Bakhai, C., Fagg, J., O’Neill, S., Young, B., Wareham, N., Khunti, K., &

Jebb S, Smith, J. (2020). Early outcomes from the English National Health Service Diabetes

Prevention Programme. Diabetes Care, 43(1), 152–160.

Westerterp, K. (2019). Exercise for weight loss. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 110(3), 40–51

WHO. (1998). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation on

obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation

(Technical Report Series No. 894). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Wynn, T., Islam, N., Thompson, C., & Myint, K. (2018). The effect of knowledge on healthcare

professionals’ perceptions of obesity. Obesity Medicine, 11, 20–24.

Xu, L., & Lam, T. H. (2018). Stage of obesity epidemic model: Learning from tobacco control and

advocacy for a framework convention on obesity control. Journal of Diabetes, 10(7), 564-571.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.