Workplace Violence Against Homecare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|13

|11142

|323

Report

AI Summary

This research article, published in BMC Public Health, presents a cross-sectional study on workplace violence experienced by homecare workers. The study, conducted in Oregon, investigated the prevalence of verbal aggression, workplace aggression, workplace violence, sexual harassment, and sexu...

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

Workplace violence against homecare workers

and its relationship with workers health

outcomes:a cross-sectionalstudy

Ginger C Hanson1*

, Nancy A Perrin1

, Helen Moss2

, Naima Laharnar3 and Nancy Glass4

Abstract

Background:Consumer-driven homecare models support aging and disabled individuals to live independent

through the services of homecare workers.Although these models have benefits,including autonomy and control

over services,little evidence exists about challenges homecare workers may face when providing services,including

workplace violence and the negative outcomes associated with workplace violence.This study investigates the

prevalence of workplace violence among homecare workers and examines the relationship between these

experiences and homecare worker stress,burnout,depression,and sleep.

Methods:We recruited female homecare workers in Oregon,the first US state to implement a consumer driven

homecare model,to complete an on-line or telephone survey with peer interviewers.The survey asked about

demographics and included measures to assess workplace violence,fear,stress,burnout,depression and sleep

problems.

Results:Homecare workers (n = 1,214) reported past-year incidents of verbalaggression (50.3% of respondents),

workplace aggression (26.9%),workplace violence (23.6%),sexualharassment (25.7%),and sexualaggression (12.8%).

Exposure was associated with greater stress (p < .001),depression (p < .001),sleep problems (p < .001),and burnout

(p < .001).Confidence in addressing workplace aggression buffered homecare workers against negative work

health outcomes.

Conclusions:To ensure homecare worker safety and positive health outcomes in the provision of services,it is

criticalto develop and implement preventive safety training programs with policies and procedures that sup

homecare workers who experience harassment and violence.

Keywords:Homecare,Workplace aggression,Workplace violence,Sexualharassment,Burnout

Background

Our global population is aging;this is true for developed

and developing nations alike [1].Reasons for this trend

include both declining fertility rates and increases in life

expectancy.The current life expectancy at birth is now

over 80 in 33 countries.Given the significance ofthis

trend,there is a need for health care policies thatwill

improve the quality of life for aging and disabled popula-

tion,their family and those caring for them.The elderly

and disabled have repeatedly expressed theirdesire to

have controlover care and remain active in their com-

munities,therefore,in an effortto meetthese appeals,

health care funding policies in mostwestern countries

for long-term care for elders and disabled persons are

shifting away from institutions,such as nursing homes

and long-term care settings to the client’s home [2].

One approach innovative to homecare is the consumer-

driven modelin the U.S.,or self-directed modelas it is

called in the UK [3].The consumer-driven model funded

through Federal/Stateentitlementprograms,such as

Medicaid/Medicare in the US,enables elderly ordis-

abled individuals in need of supportive care to continue

to live in their homes and communities while receiving

support with activities of daily living (ADLs).Homecare

* Correspondence:ginger.c.hanson@kpchr.org

1Research Data and Analysis Center,Center for Health Research,Portland,

Oregon,USA

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Hanson et al.;licensee BioMed Central.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11

DOI10.1186/s12889-014-1340-7

Workplace violence against homecare workers

and its relationship with workers health

outcomes:a cross-sectionalstudy

Ginger C Hanson1*

, Nancy A Perrin1

, Helen Moss2

, Naima Laharnar3 and Nancy Glass4

Abstract

Background:Consumer-driven homecare models support aging and disabled individuals to live independent

through the services of homecare workers.Although these models have benefits,including autonomy and control

over services,little evidence exists about challenges homecare workers may face when providing services,including

workplace violence and the negative outcomes associated with workplace violence.This study investigates the

prevalence of workplace violence among homecare workers and examines the relationship between these

experiences and homecare worker stress,burnout,depression,and sleep.

Methods:We recruited female homecare workers in Oregon,the first US state to implement a consumer driven

homecare model,to complete an on-line or telephone survey with peer interviewers.The survey asked about

demographics and included measures to assess workplace violence,fear,stress,burnout,depression and sleep

problems.

Results:Homecare workers (n = 1,214) reported past-year incidents of verbalaggression (50.3% of respondents),

workplace aggression (26.9%),workplace violence (23.6%),sexualharassment (25.7%),and sexualaggression (12.8%).

Exposure was associated with greater stress (p < .001),depression (p < .001),sleep problems (p < .001),and burnout

(p < .001).Confidence in addressing workplace aggression buffered homecare workers against negative work

health outcomes.

Conclusions:To ensure homecare worker safety and positive health outcomes in the provision of services,it is

criticalto develop and implement preventive safety training programs with policies and procedures that sup

homecare workers who experience harassment and violence.

Keywords:Homecare,Workplace aggression,Workplace violence,Sexualharassment,Burnout

Background

Our global population is aging;this is true for developed

and developing nations alike [1].Reasons for this trend

include both declining fertility rates and increases in life

expectancy.The current life expectancy at birth is now

over 80 in 33 countries.Given the significance ofthis

trend,there is a need for health care policies thatwill

improve the quality of life for aging and disabled popula-

tion,their family and those caring for them.The elderly

and disabled have repeatedly expressed theirdesire to

have controlover care and remain active in their com-

munities,therefore,in an effortto meetthese appeals,

health care funding policies in mostwestern countries

for long-term care for elders and disabled persons are

shifting away from institutions,such as nursing homes

and long-term care settings to the client’s home [2].

One approach innovative to homecare is the consumer-

driven modelin the U.S.,or self-directed modelas it is

called in the UK [3].The consumer-driven model funded

through Federal/Stateentitlementprograms,such as

Medicaid/Medicare in the US,enables elderly ordis-

abled individuals in need of supportive care to continue

to live in their homes and communities while receiving

support with activities of daily living (ADLs).Homecare

* Correspondence:ginger.c.hanson@kpchr.org

1Research Data and Analysis Center,Center for Health Research,Portland,

Oregon,USA

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2015 Hanson et al.;licensee BioMed Central.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided the originalwork is properly credited.The Creative Commons Public Domain

Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,

unless otherwise stated.

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11

DOI10.1186/s12889-014-1340-7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

workers in the consumer-driven modelare employees

of the consumer rather than an organization/institution.

The homecareworkers,often non-licensed workers,

perform ADLs such as bathing and hygiene,dressing

and grooming,eating,elimination,mobility and cogni-

tion/behavior support,as wellas IADLs such as shop-

ping,housekeeping,mealpreparation,assistance with

medication and oxygen and transportation for their em-

ployer for an assigned number of hours daily [4].

The consumer-driven homecare model has a variety of

benefitsfor the consumer-employersand homecare

workers.For consumer employers,the modelsupports

the consumer’s autonomy and controlover who is hired

as their homecare worker and how the homecare worker

implementssupportfor the ADLs. Homecare workers

reportthatthey appreciate the informalwork environ-

ment ofthe home,the ability to negotiate flexible work

hours,and the meaningfulrelationships they can forge

with their consumer-employers [5].

Although there are benefits,the consumer-employer

and homecare worker relationship has the potentialfor

safety challenges.Specifically,given the weak labor mar-

ket position ofhomecare workers and their work in the

consumer employer’s home,our previous research has

demonstrated theirvulnerability to sexualharassment

and workplace violence [4].These socialand employ-

mentissues cannot be resolved in the same manner as

employmenthealth and safety issues within a hospital,

clinic or nursing home setting where employees have ac-

cessto employmentassistanceprograms,human re-

sourcesor security personnel.For homecare workers,

the workplace is the consumer employer’s home and the

perpetrator of sexual harassment and/or violence can be

eitherthe consumeremployeror a relative orfriend

with the consumeremployer.Further,limited training

initiatives aimed to prevent or respond to sexualharass-

ment and workplace violence are available to homecare

workers,and consumer-driven program policies often do

not specifically addresssexualharassmentand/orvio-

lence perpetrated by consumer employers or others in

the home against homecare workers.

Defining workplace violence

For our study,we used the definitions provided by Bar-

ling and colleagues [6],they defined four different types

of workplace violence thathomecare workers may ex-

perience:workplaceaggression,workplaceviolence,

sexualharassment,and sexualaggression.Workplace

aggression refers to acts ofnon-physicalaggression or

threats ofviolence in the work setting (e.g.cornering

someone,slamming a door,or threatening them with a

weapon).Some studies also categorize verbal aggression

(e.g.,yelling,insulting,belittling) separately from work-

place aggression [7-9]and we choseto follow this

convention.Workplaceviolencerefersto the occur-

rence ofphysicalassaultor physically threatening be-

havior (e.g.,hitting with a fist or other object,kicking,

biting,bumping with intentionalforce).Sexualharass-

ment is defined as the occurrence of acts of a sexual na-

ture that could be deemed offensive or intimidating,but

were not physical acts (e.g., sexual comments, unwanted

requests dates or sexualfavors,leaving sexually explicit

materialin view).SexualAggression was defined as the

occurrence ofacts ofa sexualnature involving physical

contact(e.g.,breaking personalboundaries,touching

someone in a sexual way).

Workplace violence in homecare

In the US,approximately 2 million workers are affected

by workplace violence annually [10].Workplace violence

in healthcare and socialservices occupations has been

recognizedgloballyas a major occupationalhazard

[11-14].Homicide is the number one cause ofdeath in

the workplace for nurses and employees in personal-care

facilities [15].Almost half of allnon-fatalassaults in US

workplaces occur in the healthcare or socialservice in-

dustries[14].In the U.K., wherea similarmodelof

homecare isbeing implemented,assaultswere among

the top causesof workplace injuriesresulting in 7 or

more days ofmissed work in both the healthcare and

residential care industries [16].

The threat of workplace violence is one of the top con-

cerns ofhome healthcare workers,ranking higher than

environmentalhazardsor transportation issues[17].

Severalfactors,including the lack ofa large nationally

representative sample and differencesin methodology

make it difficult to narrow in on the precise prevalence

of workplace violence,but looking across severalstudies

can offer some estimate.Survey results from severaldif-

ferentstudies have shown the percentage ofhomecare

workers experiencing any form of workplace violence to

be between 5-61% [7].Verbal aggression is the most per-

vasive,reportedby between18-59% of homecare

workers [6,7,17]:with the highest estimate coming from

a study that ask about abuse over the homecare worker’s

career [7] and the lower estimates coming from studies

that ask aboutthe occurrencein the last 6-months

[6,17].Workplaceaggression,or threatening behavior

were reported by 7-16% [6,7] of homecare workers,with

the highest percentage coming from a study that asked

about the occurrence over the homecare workers career

[7],and lower percentage coming from a study that re-

ported aboutthe occurrence in the last6 months [6].

Workplace violence orphysicalassaults were reported

by between 2-11% ofhomecare workers [6,17,18],with

the larger percentage coming from a broader definition

of workplaceviolencethat included being threatened

with a knife [6],and the smallerpercentagescoming

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 2 of 13

of the consumer rather than an organization/institution.

The homecareworkers,often non-licensed workers,

perform ADLs such as bathing and hygiene,dressing

and grooming,eating,elimination,mobility and cogni-

tion/behavior support,as wellas IADLs such as shop-

ping,housekeeping,mealpreparation,assistance with

medication and oxygen and transportation for their em-

ployer for an assigned number of hours daily [4].

The consumer-driven homecare model has a variety of

benefitsfor the consumer-employersand homecare

workers.For consumer employers,the modelsupports

the consumer’s autonomy and controlover who is hired

as their homecare worker and how the homecare worker

implementssupportfor the ADLs. Homecare workers

reportthatthey appreciate the informalwork environ-

ment ofthe home,the ability to negotiate flexible work

hours,and the meaningfulrelationships they can forge

with their consumer-employers [5].

Although there are benefits,the consumer-employer

and homecare worker relationship has the potentialfor

safety challenges.Specifically,given the weak labor mar-

ket position ofhomecare workers and their work in the

consumer employer’s home,our previous research has

demonstrated theirvulnerability to sexualharassment

and workplace violence [4].These socialand employ-

mentissues cannot be resolved in the same manner as

employmenthealth and safety issues within a hospital,

clinic or nursing home setting where employees have ac-

cessto employmentassistanceprograms,human re-

sourcesor security personnel.For homecare workers,

the workplace is the consumer employer’s home and the

perpetrator of sexual harassment and/or violence can be

eitherthe consumeremployeror a relative orfriend

with the consumeremployer.Further,limited training

initiatives aimed to prevent or respond to sexualharass-

ment and workplace violence are available to homecare

workers,and consumer-driven program policies often do

not specifically addresssexualharassmentand/orvio-

lence perpetrated by consumer employers or others in

the home against homecare workers.

Defining workplace violence

For our study,we used the definitions provided by Bar-

ling and colleagues [6],they defined four different types

of workplace violence thathomecare workers may ex-

perience:workplaceaggression,workplaceviolence,

sexualharassment,and sexualaggression.Workplace

aggression refers to acts ofnon-physicalaggression or

threats ofviolence in the work setting (e.g.cornering

someone,slamming a door,or threatening them with a

weapon).Some studies also categorize verbal aggression

(e.g.,yelling,insulting,belittling) separately from work-

place aggression [7-9]and we choseto follow this

convention.Workplaceviolencerefersto the occur-

rence ofphysicalassaultor physically threatening be-

havior (e.g.,hitting with a fist or other object,kicking,

biting,bumping with intentionalforce).Sexualharass-

ment is defined as the occurrence of acts of a sexual na-

ture that could be deemed offensive or intimidating,but

were not physical acts (e.g., sexual comments, unwanted

requests dates or sexualfavors,leaving sexually explicit

materialin view).SexualAggression was defined as the

occurrence ofacts ofa sexualnature involving physical

contact(e.g.,breaking personalboundaries,touching

someone in a sexual way).

Workplace violence in homecare

In the US,approximately 2 million workers are affected

by workplace violence annually [10].Workplace violence

in healthcare and socialservices occupations has been

recognizedgloballyas a major occupationalhazard

[11-14].Homicide is the number one cause ofdeath in

the workplace for nurses and employees in personal-care

facilities [15].Almost half of allnon-fatalassaults in US

workplaces occur in the healthcare or socialservice in-

dustries[14].In the U.K., wherea similarmodelof

homecare isbeing implemented,assaultswere among

the top causesof workplace injuriesresulting in 7 or

more days ofmissed work in both the healthcare and

residential care industries [16].

The threat of workplace violence is one of the top con-

cerns ofhome healthcare workers,ranking higher than

environmentalhazardsor transportation issues[17].

Severalfactors,including the lack ofa large nationally

representative sample and differencesin methodology

make it difficult to narrow in on the precise prevalence

of workplace violence,but looking across severalstudies

can offer some estimate.Survey results from severaldif-

ferentstudies have shown the percentage ofhomecare

workers experiencing any form of workplace violence to

be between 5-61% [7].Verbal aggression is the most per-

vasive,reportedby between18-59% of homecare

workers [6,7,17]:with the highest estimate coming from

a study that ask about abuse over the homecare worker’s

career [7] and the lower estimates coming from studies

that ask aboutthe occurrencein the last 6-months

[6,17].Workplaceaggression,or threatening behavior

were reported by 7-16% [6,7] of homecare workers,with

the highest percentage coming from a study that asked

about the occurrence over the homecare workers career

[7],and lower percentage coming from a study that re-

ported aboutthe occurrence in the last6 months [6].

Workplace violence orphysicalassaults were reported

by between 2-11% ofhomecare workers [6,17,18],with

the larger percentage coming from a broader definition

of workplaceviolencethat included being threatened

with a knife [6],and the smallerpercentagescoming

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 2 of 13

from studies that included general questions about phys-

ical assaults only [17,18].

Research has shown that workplace violence and sex-

ual harassment and sexual aggression often co-occur [6].

A meta-analysiscovering 86,578 participantsfrom 55

separate probability samplesacross a variety ofindus-

tries found that 58% of women reportexperiencing

sexually harassing behaviors atwork [19].Nurses are

believed to have a higher exposure to sexual harassment

than many other occupations;studies have found that

between 16-76% ofnurses’reportexperiencing sexual

harassment over their careers [20-27].Studies of home-

care workershavefound thatapproximately30% of

homecareworkersreported beingsexuallyharassed

[6,28].While reports ofworkplace violence and sexual

harassmentare high,scientists believe thatthe actual

prevalence may be even highergiven underreporting

bias [29].

Impact on work and health outcomes

Homecareworkers’experienceof workplaceviolence

and sexualharassment can impact their health both dir-

ectly and indirectly.The most severe possible direct ef-

fect is homicide of the homecare worker [30],but more

common directeffectsare nonfatalinjuries[31-33].

While the most severe forms ofviolence occur less fre-

quently,even less-severe formsof workplace violence

and sexualharassmentare associated with a variety of

negativeoutcomesfor women’sphysicaland mental

health [34].The indirectpersonalimpactof workplace

violence on women’s health can be understood using the

Lazarus and Folkman’s transactionalstress and coping

theory [35].According to this perspective,experiences

of workplaceviolencecan overwhelm thehomecare

worker’s coping resources resulting in prolonged stress

[36,37]and leadingto poorer mentaland physical

health outcomes.Severalstudieshave documented

health effectsof workplaceviolenceon health out-

comes,including depersonalization[38]; depression

[18]; flashbacks,sleeplessness,poorer mentalhealth

[39];traumatic stress disorder [40];emotionalexhaus-

tion [38],and poorer physical health [38].Health effects

of workplace violence and harassment can last for years

after the incident(s) [41].

Research has confirmed links between workplace vio-

lence and stressorssuch as fear of future violence

[7,36,42-47],and has demonstrated that fear is a path-

way by which workplaceviolencecan affect health

[6,36].In addition,homecare workers do notneed to

experience workplace violence to reportnegative out-

comes,as studieshave shown thatfear or perceived

threat of workplaceviolenceis associated with in-

creased physicalsymptoms,anxiety,and poorer mental

health [48].Fear or perceived threat may be precipitated

by witnessing or hearing about the negative experience

of another homecare worker.Based on the transactional

stress and coping theory,confidence in preventing and

responding to workplace violence may be considered a

resource thatincreases homecare workers capacity to

cope with the stress and helps buffer the negative im-

pacts on their health.A study conducted in one private

homecare agency found that 93% ofhomecare workers

were more confidentafter participating in violence-

prevention training [49].However,they did not go fur-

ther to examine the impact of the increase in confidence

on health outcomes.

Purpose

This study examines sexualharassmentand workplace

violenceprevalencein a consumer-drivenhomecare

model,where the potentialoutcomesfor homecare

workers who experience harassment and/or violence are

not fully understood.We examined the prevalence of

different types ofworkplace violence and sexualharass-

ment as defined above,and the association of workplace

violence,sexualharassment,and fear of violence or har-

assmenton homecare worker’swork and health out-

comes.Prevalence estimatesare criticalto supporting

efforts of homecare workers and their advocates,such as

labor unions,to develop training programs and policies

to preventsexualharassmentand workplace violence.

We also examined workers’confidencein preventing

and responding to sexual harassment and workplace vio-

lence as a moderator ofthe relationship between these

experiences and negative work (e.g.burnout) and health

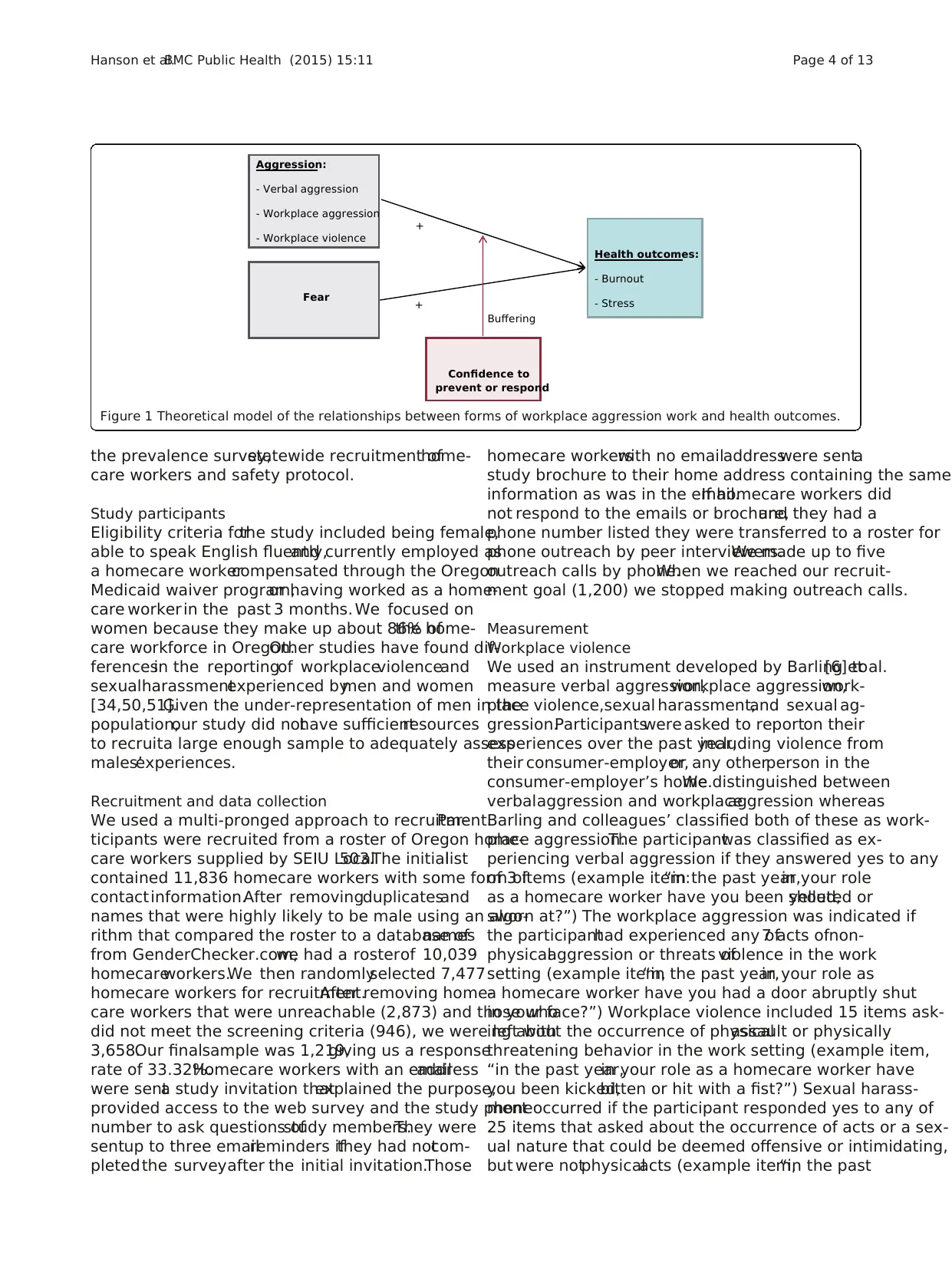

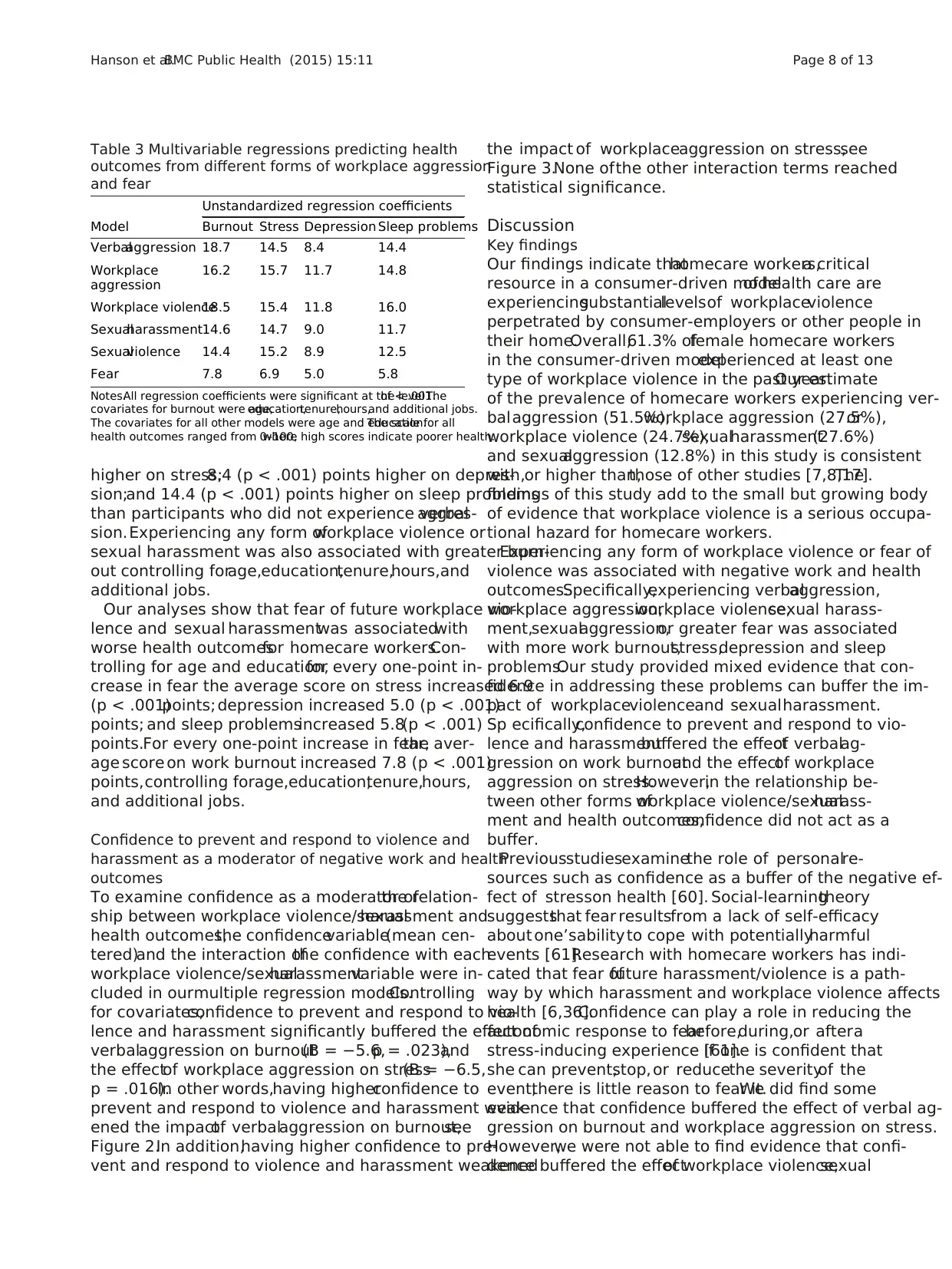

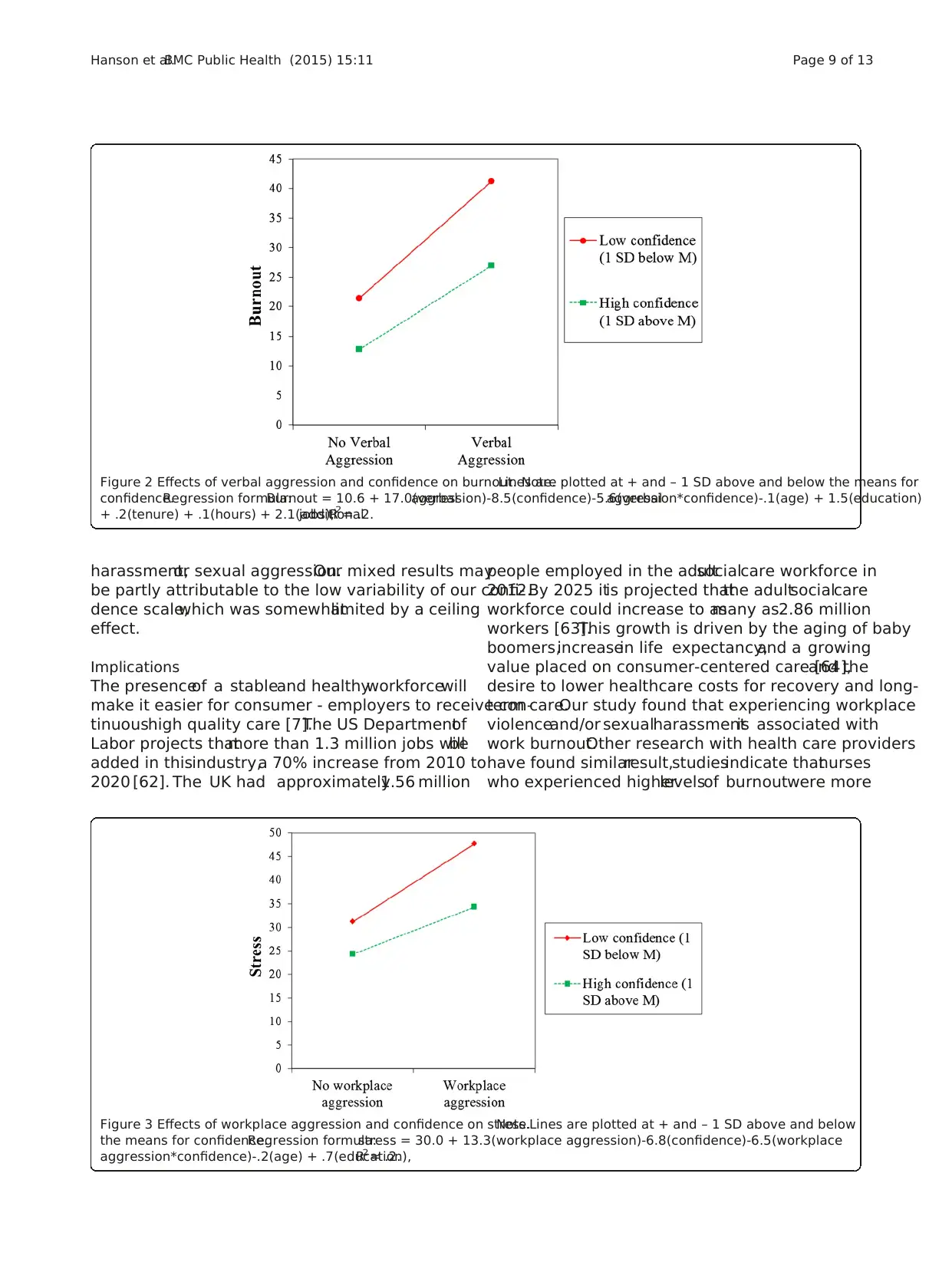

(e.g.depression)outcomes,see Figure 1.This informa-

tion is also importantto developing homecare worker

programs to reduce the negative outcomes often associ-

ated with experiencing harassment and violence.

Methods

We used a cross-sectionaldesign to explore the preva-

lence of workplace violence and sexual harassment expe-

rienced by homecareworkersin a consumer-driven

homecare modeland to understand how these experi-

ences related to homecare workers’work and health out-

comes.The study isin compliance with the Helsinki

Declaration and received oversight and approvalfor the

study from the IRBs at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

(#20685)and Oregon Health and Science University

(#4623).Our research was facilitated by a partnership

with the Oregon Homecare Commission (OHCC)and

with the Service Employees InternationalUnion (SEIU)

Local503,who also participated in our advisory board

along with members of the study team and representa-

tives for Oregon Department ofHuman Services DHS,

homecare workers,and consumer-employers.The ad-

visory board provided guidance on the development of

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 3 of 13

ical assaults only [17,18].

Research has shown that workplace violence and sex-

ual harassment and sexual aggression often co-occur [6].

A meta-analysiscovering 86,578 participantsfrom 55

separate probability samplesacross a variety ofindus-

tries found that 58% of women reportexperiencing

sexually harassing behaviors atwork [19].Nurses are

believed to have a higher exposure to sexual harassment

than many other occupations;studies have found that

between 16-76% ofnurses’reportexperiencing sexual

harassment over their careers [20-27].Studies of home-

care workershavefound thatapproximately30% of

homecareworkersreported beingsexuallyharassed

[6,28].While reports ofworkplace violence and sexual

harassmentare high,scientists believe thatthe actual

prevalence may be even highergiven underreporting

bias [29].

Impact on work and health outcomes

Homecareworkers’experienceof workplaceviolence

and sexualharassment can impact their health both dir-

ectly and indirectly.The most severe possible direct ef-

fect is homicide of the homecare worker [30],but more

common directeffectsare nonfatalinjuries[31-33].

While the most severe forms ofviolence occur less fre-

quently,even less-severe formsof workplace violence

and sexualharassmentare associated with a variety of

negativeoutcomesfor women’sphysicaland mental

health [34].The indirectpersonalimpactof workplace

violence on women’s health can be understood using the

Lazarus and Folkman’s transactionalstress and coping

theory [35].According to this perspective,experiences

of workplaceviolencecan overwhelm thehomecare

worker’s coping resources resulting in prolonged stress

[36,37]and leadingto poorer mentaland physical

health outcomes.Severalstudieshave documented

health effectsof workplaceviolenceon health out-

comes,including depersonalization[38]; depression

[18]; flashbacks,sleeplessness,poorer mentalhealth

[39];traumatic stress disorder [40];emotionalexhaus-

tion [38],and poorer physical health [38].Health effects

of workplace violence and harassment can last for years

after the incident(s) [41].

Research has confirmed links between workplace vio-

lence and stressorssuch as fear of future violence

[7,36,42-47],and has demonstrated that fear is a path-

way by which workplaceviolencecan affect health

[6,36].In addition,homecare workers do notneed to

experience workplace violence to reportnegative out-

comes,as studieshave shown thatfear or perceived

threat of workplaceviolenceis associated with in-

creased physicalsymptoms,anxiety,and poorer mental

health [48].Fear or perceived threat may be precipitated

by witnessing or hearing about the negative experience

of another homecare worker.Based on the transactional

stress and coping theory,confidence in preventing and

responding to workplace violence may be considered a

resource thatincreases homecare workers capacity to

cope with the stress and helps buffer the negative im-

pacts on their health.A study conducted in one private

homecare agency found that 93% ofhomecare workers

were more confidentafter participating in violence-

prevention training [49].However,they did not go fur-

ther to examine the impact of the increase in confidence

on health outcomes.

Purpose

This study examines sexualharassmentand workplace

violenceprevalencein a consumer-drivenhomecare

model,where the potentialoutcomesfor homecare

workers who experience harassment and/or violence are

not fully understood.We examined the prevalence of

different types ofworkplace violence and sexualharass-

ment as defined above,and the association of workplace

violence,sexualharassment,and fear of violence or har-

assmenton homecare worker’swork and health out-

comes.Prevalence estimatesare criticalto supporting

efforts of homecare workers and their advocates,such as

labor unions,to develop training programs and policies

to preventsexualharassmentand workplace violence.

We also examined workers’confidencein preventing

and responding to sexual harassment and workplace vio-

lence as a moderator ofthe relationship between these

experiences and negative work (e.g.burnout) and health

(e.g.depression)outcomes,see Figure 1.This informa-

tion is also importantto developing homecare worker

programs to reduce the negative outcomes often associ-

ated with experiencing harassment and violence.

Methods

We used a cross-sectionaldesign to explore the preva-

lence of workplace violence and sexual harassment expe-

rienced by homecareworkersin a consumer-driven

homecare modeland to understand how these experi-

ences related to homecare workers’work and health out-

comes.The study isin compliance with the Helsinki

Declaration and received oversight and approvalfor the

study from the IRBs at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

(#20685)and Oregon Health and Science University

(#4623).Our research was facilitated by a partnership

with the Oregon Homecare Commission (OHCC)and

with the Service Employees InternationalUnion (SEIU)

Local503,who also participated in our advisory board

along with members of the study team and representa-

tives for Oregon Department ofHuman Services DHS,

homecare workers,and consumer-employers.The ad-

visory board provided guidance on the development of

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 3 of 13

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

the prevalence survey,statewide recruitment ofhome-

care workers and safety protocol.

Study participants

Eligibility criteria forthe study included being female,

able to speak English fluently,and currently employed as

a homecare workercompensated through the Oregon

Medicaid waiver program,or having worked as a home-

care worker in the past 3 months. We focused on

women because they make up about 86% ofthe home-

care workforce in Oregon.Other studies have found dif-

ferencesin the reportingof workplaceviolenceand

sexualharassmentexperienced bymen and women

[34,50,51].Given the under-representation of men in the

population,our study did nothave sufficientresources

to recruita large enough sample to adequately assess

males’experiences.

Recruitment and data collection

We used a multi-pronged approach to recruitment.Par-

ticipants were recruited from a roster of Oregon home-

care workers supplied by SEIU Local503.The initiallist

contained 11,836 homecare workers with some form of

contactinformation.After removingduplicatesand

names that were highly likely to be male using an algo-

rithm that compared the roster to a database ofnames

from GenderChecker.com,we had a rosterof 10,039

homecareworkers.We then randomlyselected 7,477

homecare workers for recruitment.After removing home-

care workers that were unreachable (2,873) and those who

did not meet the screening criteria (946), we were left with

3,658.Our finalsample was 1,219,giving us a response

rate of 33.32%.Homecare workers with an emailaddress

were senta study invitation thatexplained the purpose,

provided access to the web survey and the study phone

number to ask questions ofstudy members.They were

sentup to three emailreminders ifthey had notcom-

pletedthe surveyafter the initial invitation.Those

homecare workerswith no emailaddresswere senta

study brochure to their home address containing the same

information as was in the email.If homecare workers did

not respond to the emails or brochure,and they had a

phone number listed they were transferred to a roster for

phone outreach by peer interviewers.We made up to five

outreach calls by phone.When we reached our recruit-

ment goal (1,200) we stopped making outreach calls.

Measurement

Workplace violence

We used an instrument developed by Barling et al.[6] to

measure verbal aggression,workplace aggression,work-

place violence,sexual harassment,and sexual ag-

gression.Participantswere asked to reporton their

experiences over the past year,including violence from

their consumer-employer,or any otherperson in the

consumer-employer’s home.We distinguished between

verbalaggression and workplaceaggression whereas

Barling and colleagues’ classified both of these as work-

place aggression.The participantwas classified as ex-

periencing verbal aggression if they answered yes to any

of 3 items (example item:“in the past year,in your role

as a homecare worker have you been yelled,shouted or

sworn at?”) The workplace aggression was indicated if

the participanthad experienced any of7 acts ofnon-

physicalaggression or threats ofviolence in the work

setting (example item,“in the past year,in your role as

a homecare worker have you had a door abruptly shut

in your face?”) Workplace violence included 15 items ask-

ing about the occurrence of physicalassault or physically

threatening behavior in the work setting (example item,

“in the past year,in your role as a homecare worker have

you been kicked,bitten or hit with a fist?”) Sexual harass-

ment occurred if the participant responded yes to any of

25 items that asked about the occurrence of acts or a sex-

ual nature that could be deemed offensive or intimidating,

but were notphysicalacts (example item,“in the past

Aggression:

- Verbal aggression

- Workplace aggression

- Workplace violence

Health outcomes:

- Burnout

- Stress

Fear

Confidence to

prevent or respond

+

+

Buffering

Figure 1 Theoretical model of the relationships between forms of workplace aggression work and health outcomes.

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 4 of 13

care workers and safety protocol.

Study participants

Eligibility criteria forthe study included being female,

able to speak English fluently,and currently employed as

a homecare workercompensated through the Oregon

Medicaid waiver program,or having worked as a home-

care worker in the past 3 months. We focused on

women because they make up about 86% ofthe home-

care workforce in Oregon.Other studies have found dif-

ferencesin the reportingof workplaceviolenceand

sexualharassmentexperienced bymen and women

[34,50,51].Given the under-representation of men in the

population,our study did nothave sufficientresources

to recruita large enough sample to adequately assess

males’experiences.

Recruitment and data collection

We used a multi-pronged approach to recruitment.Par-

ticipants were recruited from a roster of Oregon home-

care workers supplied by SEIU Local503.The initiallist

contained 11,836 homecare workers with some form of

contactinformation.After removingduplicatesand

names that were highly likely to be male using an algo-

rithm that compared the roster to a database ofnames

from GenderChecker.com,we had a rosterof 10,039

homecareworkers.We then randomlyselected 7,477

homecare workers for recruitment.After removing home-

care workers that were unreachable (2,873) and those who

did not meet the screening criteria (946), we were left with

3,658.Our finalsample was 1,219,giving us a response

rate of 33.32%.Homecare workers with an emailaddress

were senta study invitation thatexplained the purpose,

provided access to the web survey and the study phone

number to ask questions ofstudy members.They were

sentup to three emailreminders ifthey had notcom-

pletedthe surveyafter the initial invitation.Those

homecare workerswith no emailaddresswere senta

study brochure to their home address containing the same

information as was in the email.If homecare workers did

not respond to the emails or brochure,and they had a

phone number listed they were transferred to a roster for

phone outreach by peer interviewers.We made up to five

outreach calls by phone.When we reached our recruit-

ment goal (1,200) we stopped making outreach calls.

Measurement

Workplace violence

We used an instrument developed by Barling et al.[6] to

measure verbal aggression,workplace aggression,work-

place violence,sexual harassment,and sexual ag-

gression.Participantswere asked to reporton their

experiences over the past year,including violence from

their consumer-employer,or any otherperson in the

consumer-employer’s home.We distinguished between

verbalaggression and workplaceaggression whereas

Barling and colleagues’ classified both of these as work-

place aggression.The participantwas classified as ex-

periencing verbal aggression if they answered yes to any

of 3 items (example item:“in the past year,in your role

as a homecare worker have you been yelled,shouted or

sworn at?”) The workplace aggression was indicated if

the participanthad experienced any of7 acts ofnon-

physicalaggression or threats ofviolence in the work

setting (example item,“in the past year,in your role as

a homecare worker have you had a door abruptly shut

in your face?”) Workplace violence included 15 items ask-

ing about the occurrence of physicalassault or physically

threatening behavior in the work setting (example item,

“in the past year,in your role as a homecare worker have

you been kicked,bitten or hit with a fist?”) Sexual harass-

ment occurred if the participant responded yes to any of

25 items that asked about the occurrence of acts or a sex-

ual nature that could be deemed offensive or intimidating,

but were notphysicalacts (example item,“in the past

Aggression:

- Verbal aggression

- Workplace aggression

- Workplace violence

Health outcomes:

- Burnout

- Stress

Fear

Confidence to

prevent or respond

+

+

Buffering

Figure 1 Theoretical model of the relationships between forms of workplace aggression work and health outcomes.

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 4 of 13

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

year,in your role as a homecare worker have you had

sexually explicit material left in view?”).The participant

was classified as experiencing SexualAggression if they

indicated that any 11 acts ofa sexualnature involving

physicalcontact(example item,“in the pastyear,in

your role as a homecare worker have you been touched

in a sexual way?”) had occurred.

Fear

For the purpose ofthis study,fear is defined asthe

worry thatone will experience some form ofviolence

while working asa homecare workers.We measured

fear by adapting the scale used by Barling et al.[6].After

each section ofthe questions(e.g.,workplace aggres-

sion),participantswere asked to indicate theiragree-

ment or disagreement with the statement,“I worry that I

will experience workplace aggression while performing

my dutiesas a homecare worker.”A similar question

was asked after the sections on workplace violence,sex-

ual harassment,and sexual aggression.These items were

rated on a 5-point Likert-typescaleranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).We calculated a

totalscore as the mean of these 4 items.The validity of

the Barling etal. scale hasbeen established in other

studieswith homecareworkers[6,36].The internal

consistency,or Cronbach’s alpha,for these items was .90

in our sample.

Burnout

We used a subset ofeight items from the work-related

burnoutand client-related burnoutsubscalesof the

Copenhagan Burnout Inventory (CBI) developed for the

PUMA study [52].The validityof this measurewas

established in a large sample ofhuman service workers

[53].In our sample the two subscales used in the PUMA

study were highly correlated.An exploratory-factor

analysisindicated thattherewas a singlefactor,see

Additionalfile 1.As a result,we collapsed them into a

single work related burnout scale.Work related burnout

can be defined as “a state of prolonged physical and psy-

chologicalexhaustion,which is perceived as related to

the person’s work” [54].An example item is,“thinking

aboutthe last4 weeks,is your work as a homecare

worker emotionally exhausting?”The items were mea-

sured on a 5-pointscale.We obtained a totalscore by

taking the mean of the items and then rescaling so that

the final score would range from 0–100.The Cronbach’s

alpha for this scale was .9.

Stress,depression and sleep

We measured stress,depression,and sleep using the

COPSOQ II [55].Each subscale had fouritems.The

introduction asked participants to think about how often

in the past 4 weeks they had experienced each item due

to working as a homecare worker.The developers of the

COPSOQ II describe stress as a personal state character-

ized by both heightened arousaland displeasure.An ex-

ampleitems is, “how often haveyou had problems

relaxing?” The COPSOQ IImeasure ofdepression was

designed to measure the levelof depressive symptoms

experienced by workers rather than to diagnose clinical

depression.An example item is,“how often have you felt

sad?”The sleep subscale is meantto be a measure of

generalsleeping troubles in a working population.An

example item is,“how often have you found ithard to

go to sleep?” All items were asked on a scale of 1 (not at

all),2 (a small part of the time),3 (part of the time),4 (a

large part of the time) or 5 (all the time).We obtained a

totalscore by taking the mean of the items and then re-

scaling so that the finalscore would range from 0–100.

The validity ofthese sub-scales has been established by

in previousresearch [56].The Cronbach’salphasfor

these scales were:α = .9stess, α = .8depression, and α = .9sleep.

Confidence

We measured an individual’s confidence thatshe could

preventand respond to workplace violence and sexual

harassmentusing a 19-item scale developed specifically

for this study.We developed an initial list of items based

on focus groups conducted by the study team with 83

homecare workers [4].Then we sent these items to five

subject-matter experts and asked them to rate the items

from 0–2 on clarity,relevance,and usability.We retained

items with a high mean on all three rating scales. The final

rating scale for the items was 1 (not at all confident),2 (a

little confident),3 (confident),or 4 (very confident).See

Additionalfile 2 for finalscale.Cronbach’s alpha for this

scale was .9.

Covariates

Age was measured in number ofyears.Education was

coded as 1 (8th grade or less),2 (some high school),3

(high school diploma or GED),4 (some college),5 (asso-

ciate’s degree or vocationalgraduate),6 (4 year college

degree/bachelor’sdegree),or 7 (post-Baccalaureate/

Master’s degree/Ph.D).Tenure was coded as the num-

ber ofyears the participant has worked as a homecare

worker.Hours worked was coded as the average num-

ber of hours worked weeklyas a homecare worker.

Additionaljobs was coded as 0 (no additionaljobs out-

side of homecare)or 1 (one or more jobs outside of

homecare).

Statistical analyses

We conducted three sets ofanalyses to answer the fol-

lowing questions:1) what is the prevalence ofdifferent

forms of workplaceviolenceand sexualharassment

among female homecare workers;2) are experiences of

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 5 of 13

sexually explicit material left in view?”).The participant

was classified as experiencing SexualAggression if they

indicated that any 11 acts ofa sexualnature involving

physicalcontact(example item,“in the pastyear,in

your role as a homecare worker have you been touched

in a sexual way?”) had occurred.

Fear

For the purpose ofthis study,fear is defined asthe

worry thatone will experience some form ofviolence

while working asa homecare workers.We measured

fear by adapting the scale used by Barling et al.[6].After

each section ofthe questions(e.g.,workplace aggres-

sion),participantswere asked to indicate theiragree-

ment or disagreement with the statement,“I worry that I

will experience workplace aggression while performing

my dutiesas a homecare worker.”A similar question

was asked after the sections on workplace violence,sex-

ual harassment,and sexual aggression.These items were

rated on a 5-point Likert-typescaleranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).We calculated a

totalscore as the mean of these 4 items.The validity of

the Barling etal. scale hasbeen established in other

studieswith homecareworkers[6,36].The internal

consistency,or Cronbach’s alpha,for these items was .90

in our sample.

Burnout

We used a subset ofeight items from the work-related

burnoutand client-related burnoutsubscalesof the

Copenhagan Burnout Inventory (CBI) developed for the

PUMA study [52].The validityof this measurewas

established in a large sample ofhuman service workers

[53].In our sample the two subscales used in the PUMA

study were highly correlated.An exploratory-factor

analysisindicated thattherewas a singlefactor,see

Additionalfile 1.As a result,we collapsed them into a

single work related burnout scale.Work related burnout

can be defined as “a state of prolonged physical and psy-

chologicalexhaustion,which is perceived as related to

the person’s work” [54].An example item is,“thinking

aboutthe last4 weeks,is your work as a homecare

worker emotionally exhausting?”The items were mea-

sured on a 5-pointscale.We obtained a totalscore by

taking the mean of the items and then rescaling so that

the final score would range from 0–100.The Cronbach’s

alpha for this scale was .9.

Stress,depression and sleep

We measured stress,depression,and sleep using the

COPSOQ II [55].Each subscale had fouritems.The

introduction asked participants to think about how often

in the past 4 weeks they had experienced each item due

to working as a homecare worker.The developers of the

COPSOQ II describe stress as a personal state character-

ized by both heightened arousaland displeasure.An ex-

ampleitems is, “how often haveyou had problems

relaxing?” The COPSOQ IImeasure ofdepression was

designed to measure the levelof depressive symptoms

experienced by workers rather than to diagnose clinical

depression.An example item is,“how often have you felt

sad?”The sleep subscale is meantto be a measure of

generalsleeping troubles in a working population.An

example item is,“how often have you found ithard to

go to sleep?” All items were asked on a scale of 1 (not at

all),2 (a small part of the time),3 (part of the time),4 (a

large part of the time) or 5 (all the time).We obtained a

totalscore by taking the mean of the items and then re-

scaling so that the finalscore would range from 0–100.

The validity ofthese sub-scales has been established by

in previousresearch [56].The Cronbach’salphasfor

these scales were:α = .9stess, α = .8depression, and α = .9sleep.

Confidence

We measured an individual’s confidence thatshe could

preventand respond to workplace violence and sexual

harassmentusing a 19-item scale developed specifically

for this study.We developed an initial list of items based

on focus groups conducted by the study team with 83

homecare workers [4].Then we sent these items to five

subject-matter experts and asked them to rate the items

from 0–2 on clarity,relevance,and usability.We retained

items with a high mean on all three rating scales. The final

rating scale for the items was 1 (not at all confident),2 (a

little confident),3 (confident),or 4 (very confident).See

Additionalfile 2 for finalscale.Cronbach’s alpha for this

scale was .9.

Covariates

Age was measured in number ofyears.Education was

coded as 1 (8th grade or less),2 (some high school),3

(high school diploma or GED),4 (some college),5 (asso-

ciate’s degree or vocationalgraduate),6 (4 year college

degree/bachelor’sdegree),or 7 (post-Baccalaureate/

Master’s degree/Ph.D).Tenure was coded as the num-

ber ofyears the participant has worked as a homecare

worker.Hours worked was coded as the average num-

ber of hours worked weeklyas a homecare worker.

Additionaljobs was coded as 0 (no additionaljobs out-

side of homecare)or 1 (one or more jobs outside of

homecare).

Statistical analyses

We conducted three sets ofanalyses to answer the fol-

lowing questions:1) what is the prevalence ofdifferent

forms of workplaceviolenceand sexualharassment

among female homecare workers;2) are experiences of

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 5 of 13

workplace violence and fearrelated to negative work

and health outcomes;and,3) are these effects moder-

ated by confidence in preventing and responding to

workplace violence.We computed prevalence asthe

percentof respondentsexperiencing each item,and

overallscores as the percentof respondents experien-

cing one or more items for each ofthe violence cate-

gories (i.e., verbalaggression,workplaceaggression,

workplace violence,sexualharassment,sexualaggres-

sion, and fear).Homecare workers providing services

for their spouseswere excludedfrom the sexual-

harassment analyses.Scores for scales with more than 3

items were computed using mean replacement from the

participant’s answered items if at least 75% of the ques-

tions were answered.

We used separate multiple regression analyses to re-

gress each violence scale on each health outcome (stress,

depression,and sleep) controlling for covariates.Poorer

health outcomes are associated with increased age and

lowersocioeconomic [57,58],for this reason,age and

education were included in allof the regression analyses

to partial out any confounding effects.Burnout is known

to be associated with work-related demographics[59].

Therefore,potentialwork related confounders including

tenure,number ofhours worked,and having additional

jobs,were also included in the model when burnout was

the outcome.

Results

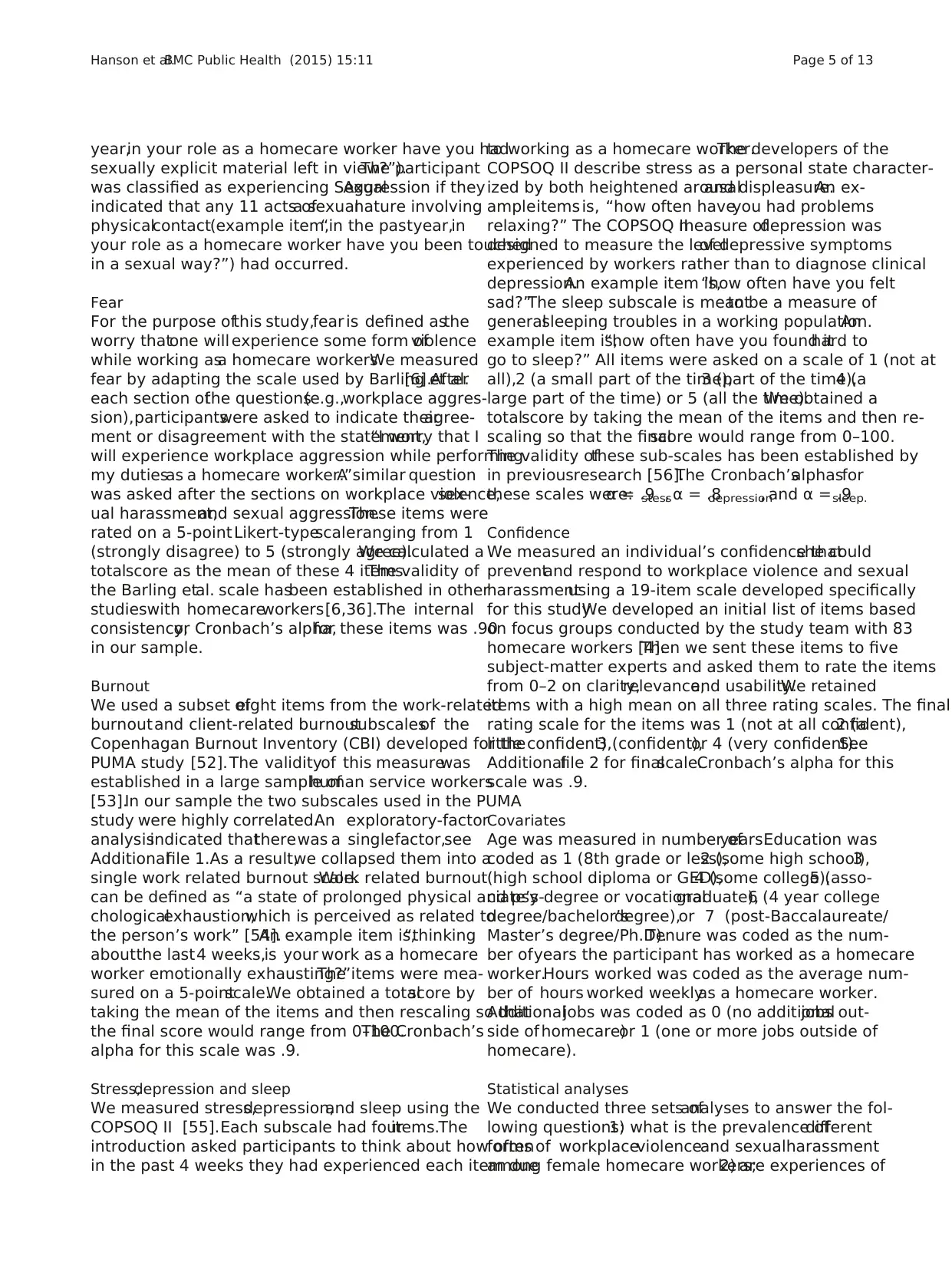

Table 1 shows demographic and work characteristics of

the 1,214 homecare workers who completed the survey.

Participants ranged in age from 19 to 80,with a mean

age of 47.30(SD = 13.8).The majorityof homecare

workers were White (85.4%),with 6.7% self-reported as

Hispanic or Latina. Almost all of the participants

(93.1%)had a high schooldiploma or GED,and 25.1%

had a college or vocationaldegree.Participants reported

having worked,on average,7. 9 (SD = 7.3)yearsas a

homecare worker.Twenty-one percentof participants

lived with their consumer-employer.The average num-

ber of hours worked perweek was33.5 (SD = 27.6).

Thirty-one participants worked for more than one con-

sumer/employer,with the average working for between

1–2 consumer-employers(M = 1.5,SD = .8).The over-

whelming majority ofhomecare workers provided ser-

vices for someone other than their spouse atleastpart

of the time (97.9%).

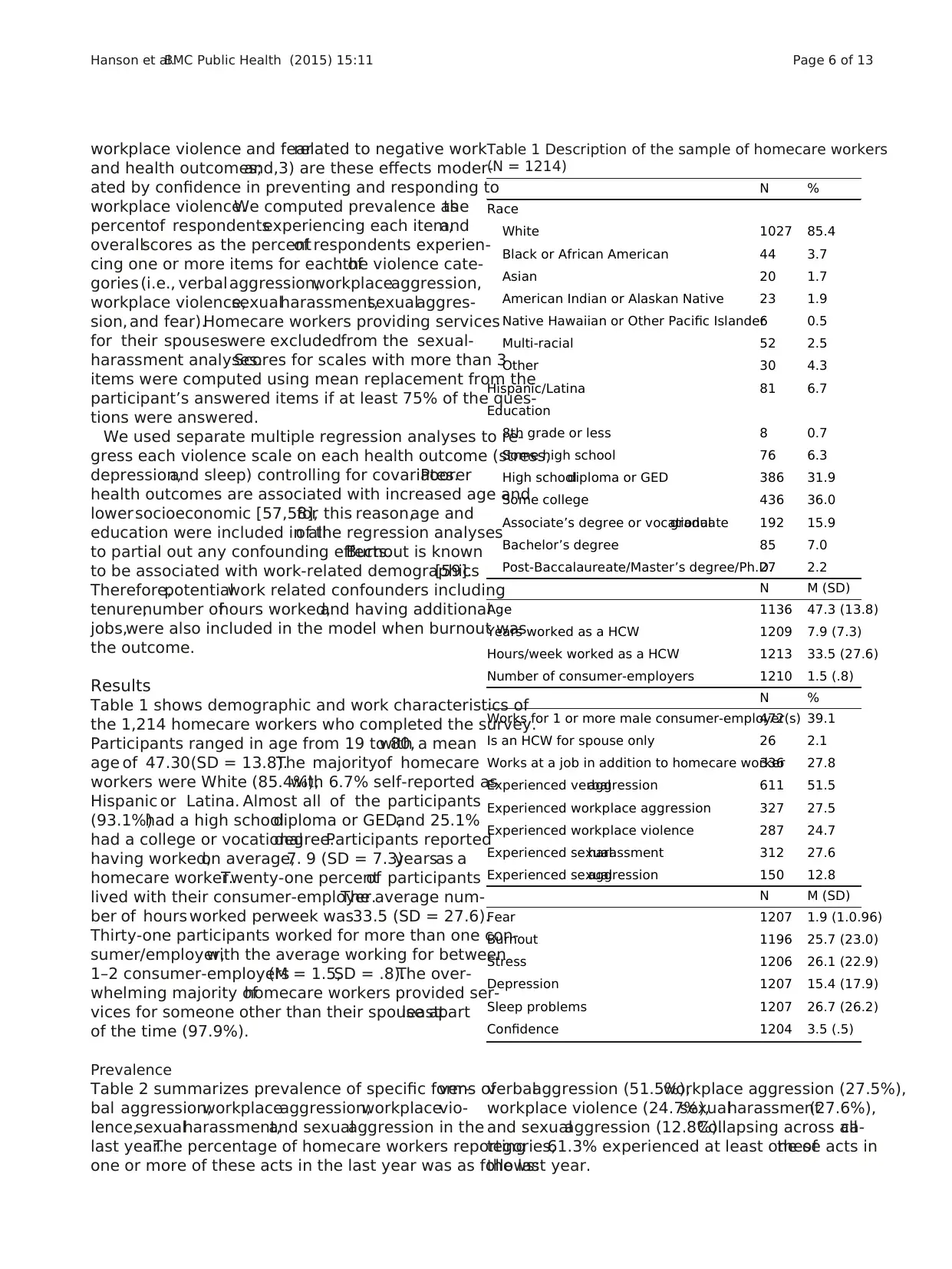

Prevalence

Table 2 summarizes prevalence of specific forms ofver-

bal aggression,workplaceaggression,workplacevio-

lence,sexualharassment,and sexualaggression in the

last year.The percentage of homecare workers reporting

one or more of these acts in the last year was as follows:

verbalaggression (51.5%),workplace aggression (27.5%),

workplace violence (24.7%),sexualharassment(27.6%),

and sexualaggression (12.8%).Collapsing across allca-

tegories,61.3% experienced at least one ofthese acts in

the last year.

Table 1 Description of the sample of homecare workers

(N = 1214)

N %

Race

White 1027 85.4

Black or African American 44 3.7

Asian 20 1.7

American Indian or Alaskan Native 23 1.9

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander6 0.5

Multi-racial 52 2.5

Other 30 4.3

Hispanic/Latina 81 6.7

Education

8th grade or less 8 0.7

Some high school 76 6.3

High schooldiploma or GED 386 31.9

Some college 436 36.0

Associate’s degree or vocationalgraduate 192 15.9

Bachelor’s degree 85 7.0

Post-Baccalaureate/Master’s degree/Ph.D.27 2.2

N M (SD)

Age 1136 47.3 (13.8)

Years worked as a HCW 1209 7.9 (7.3)

Hours/week worked as a HCW 1213 33.5 (27.6)

Number of consumer-employers 1210 1.5 (.8)

N %

Works for 1 or more male consumer-employer(s)472 39.1

Is an HCW for spouse only 26 2.1

Works at a job in addition to homecare worker336 27.8

Experienced verbalaggression 611 51.5

Experienced workplace aggression 327 27.5

Experienced workplace violence 287 24.7

Experienced sexualharassment 312 27.6

Experienced sexualaggression 150 12.8

N M (SD)

Fear 1207 1.9 (1.0.96)

Burnout 1196 25.7 (23.0)

Stress 1206 26.1 (22.9)

Depression 1207 15.4 (17.9)

Sleep problems 1207 26.7 (26.2)

Confidence 1204 3.5 (.5)

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 6 of 13

and health outcomes;and,3) are these effects moder-

ated by confidence in preventing and responding to

workplace violence.We computed prevalence asthe

percentof respondentsexperiencing each item,and

overallscores as the percentof respondents experien-

cing one or more items for each ofthe violence cate-

gories (i.e., verbalaggression,workplaceaggression,

workplace violence,sexualharassment,sexualaggres-

sion, and fear).Homecare workers providing services

for their spouseswere excludedfrom the sexual-

harassment analyses.Scores for scales with more than 3

items were computed using mean replacement from the

participant’s answered items if at least 75% of the ques-

tions were answered.

We used separate multiple regression analyses to re-

gress each violence scale on each health outcome (stress,

depression,and sleep) controlling for covariates.Poorer

health outcomes are associated with increased age and

lowersocioeconomic [57,58],for this reason,age and

education were included in allof the regression analyses

to partial out any confounding effects.Burnout is known

to be associated with work-related demographics[59].

Therefore,potentialwork related confounders including

tenure,number ofhours worked,and having additional

jobs,were also included in the model when burnout was

the outcome.

Results

Table 1 shows demographic and work characteristics of

the 1,214 homecare workers who completed the survey.

Participants ranged in age from 19 to 80,with a mean

age of 47.30(SD = 13.8).The majorityof homecare

workers were White (85.4%),with 6.7% self-reported as

Hispanic or Latina. Almost all of the participants

(93.1%)had a high schooldiploma or GED,and 25.1%

had a college or vocationaldegree.Participants reported

having worked,on average,7. 9 (SD = 7.3)yearsas a

homecare worker.Twenty-one percentof participants

lived with their consumer-employer.The average num-

ber of hours worked perweek was33.5 (SD = 27.6).

Thirty-one participants worked for more than one con-

sumer/employer,with the average working for between

1–2 consumer-employers(M = 1.5,SD = .8).The over-

whelming majority ofhomecare workers provided ser-

vices for someone other than their spouse atleastpart

of the time (97.9%).

Prevalence

Table 2 summarizes prevalence of specific forms ofver-

bal aggression,workplaceaggression,workplacevio-

lence,sexualharassment,and sexualaggression in the

last year.The percentage of homecare workers reporting

one or more of these acts in the last year was as follows:

verbalaggression (51.5%),workplace aggression (27.5%),

workplace violence (24.7%),sexualharassment(27.6%),

and sexualaggression (12.8%).Collapsing across allca-

tegories,61.3% experienced at least one ofthese acts in

the last year.

Table 1 Description of the sample of homecare workers

(N = 1214)

N %

Race

White 1027 85.4

Black or African American 44 3.7

Asian 20 1.7

American Indian or Alaskan Native 23 1.9

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander6 0.5

Multi-racial 52 2.5

Other 30 4.3

Hispanic/Latina 81 6.7

Education

8th grade or less 8 0.7

Some high school 76 6.3

High schooldiploma or GED 386 31.9

Some college 436 36.0

Associate’s degree or vocationalgraduate 192 15.9

Bachelor’s degree 85 7.0

Post-Baccalaureate/Master’s degree/Ph.D.27 2.2

N M (SD)

Age 1136 47.3 (13.8)

Years worked as a HCW 1209 7.9 (7.3)

Hours/week worked as a HCW 1213 33.5 (27.6)

Number of consumer-employers 1210 1.5 (.8)

N %

Works for 1 or more male consumer-employer(s)472 39.1

Is an HCW for spouse only 26 2.1

Works at a job in addition to homecare worker336 27.8

Experienced verbalaggression 611 51.5

Experienced workplace aggression 327 27.5

Experienced workplace violence 287 24.7

Experienced sexualharassment 312 27.6

Experienced sexualaggression 150 12.8

N M (SD)

Fear 1207 1.9 (1.0.96)

Burnout 1196 25.7 (23.0)

Stress 1206 26.1 (22.9)

Depression 1207 15.4 (17.9)

Sleep problems 1207 26.7 (26.2)

Confidence 1204 3.5 (.5)

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 6 of 13

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

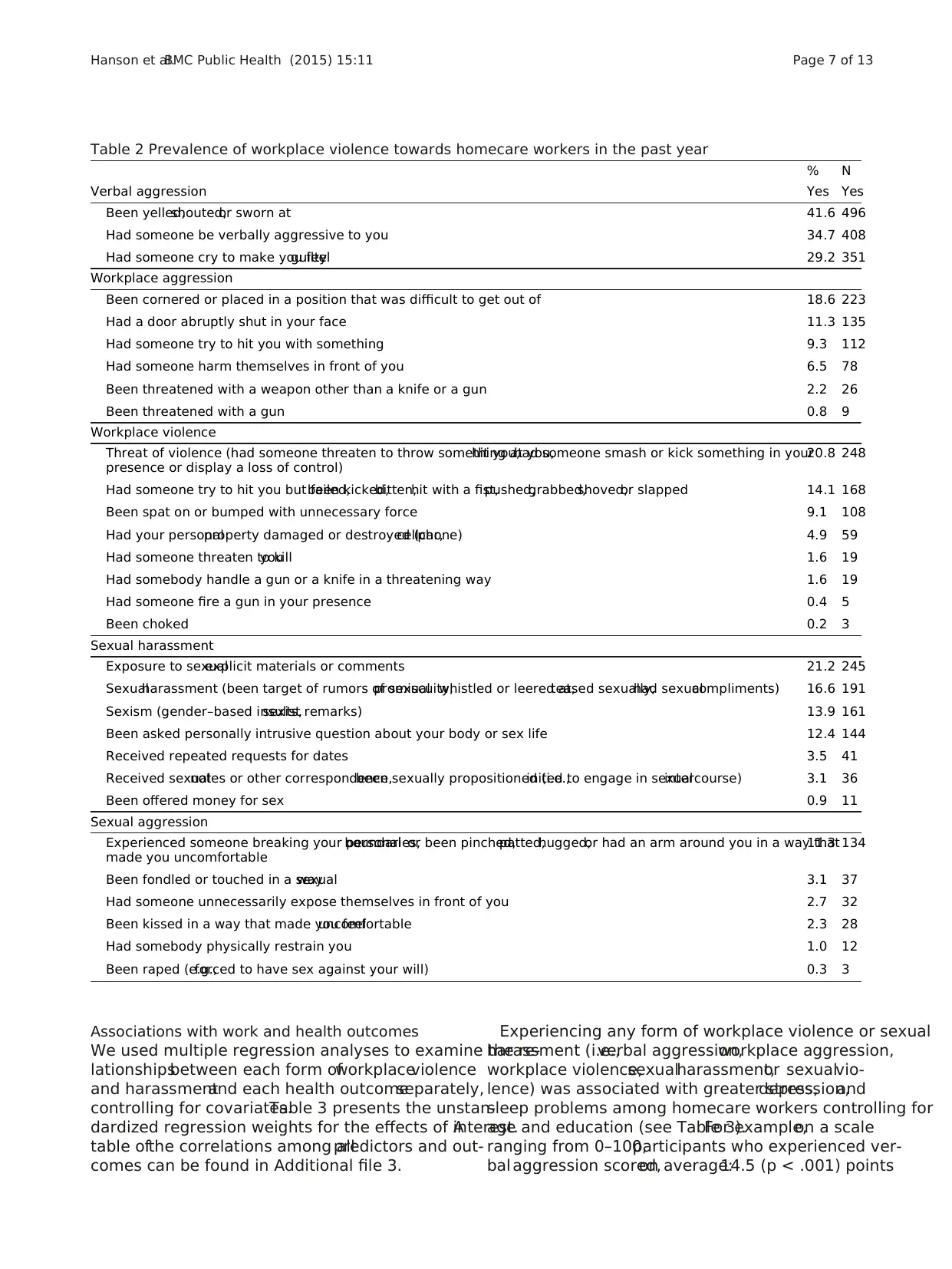

Associations with work and health outcomes

We used multiple regression analyses to examine the re-

lationshipsbetween each form ofworkplaceviolence

and harassmentand each health outcomeseparately,

controlling for covariates.Table 3 presents the unstan-

dardized regression weights for the effects of interest.A

table ofthe correlations among allpredictors and out-

comes can be found in Additional file 3.

Experiencing any form of workplace violence or sexual

harassment (i.e.,verbal aggression,workplace aggression,

workplace violence,sexualharassment,or sexualvio-

lence) was associated with greater stress,depression,and

sleep problems among homecare workers controlling for

age and education (see Table 3).For example,on a scale

ranging from 0–100,participants who experienced ver-

bal aggression scored,on average:14.5 (p < .001) points

Table 2 Prevalence of workplace violence towards homecare workers in the past year

% N

Verbal aggression Yes Yes

Been yelled,shouted,or sworn at 41.6 496

Had someone be verbally aggressive to you 34.7 408

Had someone cry to make you feelguilty 29.2 351

Workplace aggression

Been cornered or placed in a position that was difficult to get out of 18.6 223

Had a door abruptly shut in your face 11.3 135

Had someone try to hit you with something 9.3 112

Had someone harm themselves in front of you 6.5 78

Been threatened with a weapon other than a knife or a gun 2.2 26

Been threatened with a gun 0.8 9

Workplace violence

Threat of violence (had someone threaten to throw something at you,hit you,had someone smash or kick something in your

presence or display a loss of control)

20.8 248

Had someone try to hit you but failed,been kicked,bitten,hit with a fist,pushed,grabbed,shoved,or slapped 14.1 168

Been spat on or bumped with unnecessary force 9.1 108

Had your personalproperty damaged or destroyed (car,cellphone) 4.9 59

Had someone threaten to killyou 1.6 19

Had somebody handle a gun or a knife in a threatening way 1.6 19

Had someone fire a gun in your presence 0.4 5

Been choked 0.2 3

Sexual harassment

Exposure to sexualexplicit materials or comments 21.2 245

Sexualharassment (been target of rumors of sexualpromiscuity,whistled or leered at,teased sexually,had sexualcompliments) 16.6 191

Sexism (gender–based insults,sexist remarks) 13.9 161

Been asked personally intrusive question about your body or sex life 12.4 144

Received repeated requests for dates 3.5 41

Received sexualnotes or other correspondence,been sexually propositioned (i.e.,inited to engage in sexualintercourse) 3.1 36

Been offered money for sex 0.9 11

Sexual aggression

Experienced someone breaking your personalboundaries,or been pinched,patted,hugged,or had an arm around you in a way that

made you uncomfortable

11.3 134

Been fondled or touched in a sexualway 3.1 37

Had someone unnecessarily expose themselves in front of you 2.7 32

Been kissed in a way that made you feeluncomfortable 2.3 28

Had somebody physically restrain you 1.0 12

Been raped (e.g.,forced to have sex against your will) 0.3 3

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 7 of 13

We used multiple regression analyses to examine the re-

lationshipsbetween each form ofworkplaceviolence

and harassmentand each health outcomeseparately,

controlling for covariates.Table 3 presents the unstan-

dardized regression weights for the effects of interest.A

table ofthe correlations among allpredictors and out-

comes can be found in Additional file 3.

Experiencing any form of workplace violence or sexual

harassment (i.e.,verbal aggression,workplace aggression,

workplace violence,sexualharassment,or sexualvio-

lence) was associated with greater stress,depression,and

sleep problems among homecare workers controlling for

age and education (see Table 3).For example,on a scale

ranging from 0–100,participants who experienced ver-

bal aggression scored,on average:14.5 (p < .001) points

Table 2 Prevalence of workplace violence towards homecare workers in the past year

% N

Verbal aggression Yes Yes

Been yelled,shouted,or sworn at 41.6 496

Had someone be verbally aggressive to you 34.7 408

Had someone cry to make you feelguilty 29.2 351

Workplace aggression

Been cornered or placed in a position that was difficult to get out of 18.6 223

Had a door abruptly shut in your face 11.3 135

Had someone try to hit you with something 9.3 112

Had someone harm themselves in front of you 6.5 78

Been threatened with a weapon other than a knife or a gun 2.2 26

Been threatened with a gun 0.8 9

Workplace violence

Threat of violence (had someone threaten to throw something at you,hit you,had someone smash or kick something in your

presence or display a loss of control)

20.8 248

Had someone try to hit you but failed,been kicked,bitten,hit with a fist,pushed,grabbed,shoved,or slapped 14.1 168

Been spat on or bumped with unnecessary force 9.1 108

Had your personalproperty damaged or destroyed (car,cellphone) 4.9 59

Had someone threaten to killyou 1.6 19

Had somebody handle a gun or a knife in a threatening way 1.6 19

Had someone fire a gun in your presence 0.4 5

Been choked 0.2 3

Sexual harassment

Exposure to sexualexplicit materials or comments 21.2 245

Sexualharassment (been target of rumors of sexualpromiscuity,whistled or leered at,teased sexually,had sexualcompliments) 16.6 191

Sexism (gender–based insults,sexist remarks) 13.9 161

Been asked personally intrusive question about your body or sex life 12.4 144

Received repeated requests for dates 3.5 41

Received sexualnotes or other correspondence,been sexually propositioned (i.e.,inited to engage in sexualintercourse) 3.1 36

Been offered money for sex 0.9 11

Sexual aggression

Experienced someone breaking your personalboundaries,or been pinched,patted,hugged,or had an arm around you in a way that

made you uncomfortable

11.3 134

Been fondled or touched in a sexualway 3.1 37

Had someone unnecessarily expose themselves in front of you 2.7 32

Been kissed in a way that made you feeluncomfortable 2.3 28

Had somebody physically restrain you 1.0 12

Been raped (e.g.,forced to have sex against your will) 0.3 3

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 7 of 13

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

higher on stress;8.4 (p < .001) points higher on depres-

sion;and 14.4 (p < .001) points higher on sleep problems

than participants who did not experience verbalaggres-

sion.Experiencing any form ofworkplace violence or

sexual harassment was also associated with greater burn-

out controlling forage,education,tenure,hours,and

additional jobs.

Our analyses show that fear of future workplace vio-

lence and sexual harassmentwas associatedwith

worse health outcomesfor homecare workers.Con-

trolling for age and education,for every one-point in-

crease in fear the average score on stress increased 6.9

(p < .001)points; depression increased 5.0 (p < .001)

points; and sleep problemsincreased 5.8(p < .001)

points.For every one-point increase in fear,the aver-

age score on work burnout increased 7.8 (p < .001)

points,controlling forage,education,tenure,hours,

and additional jobs.

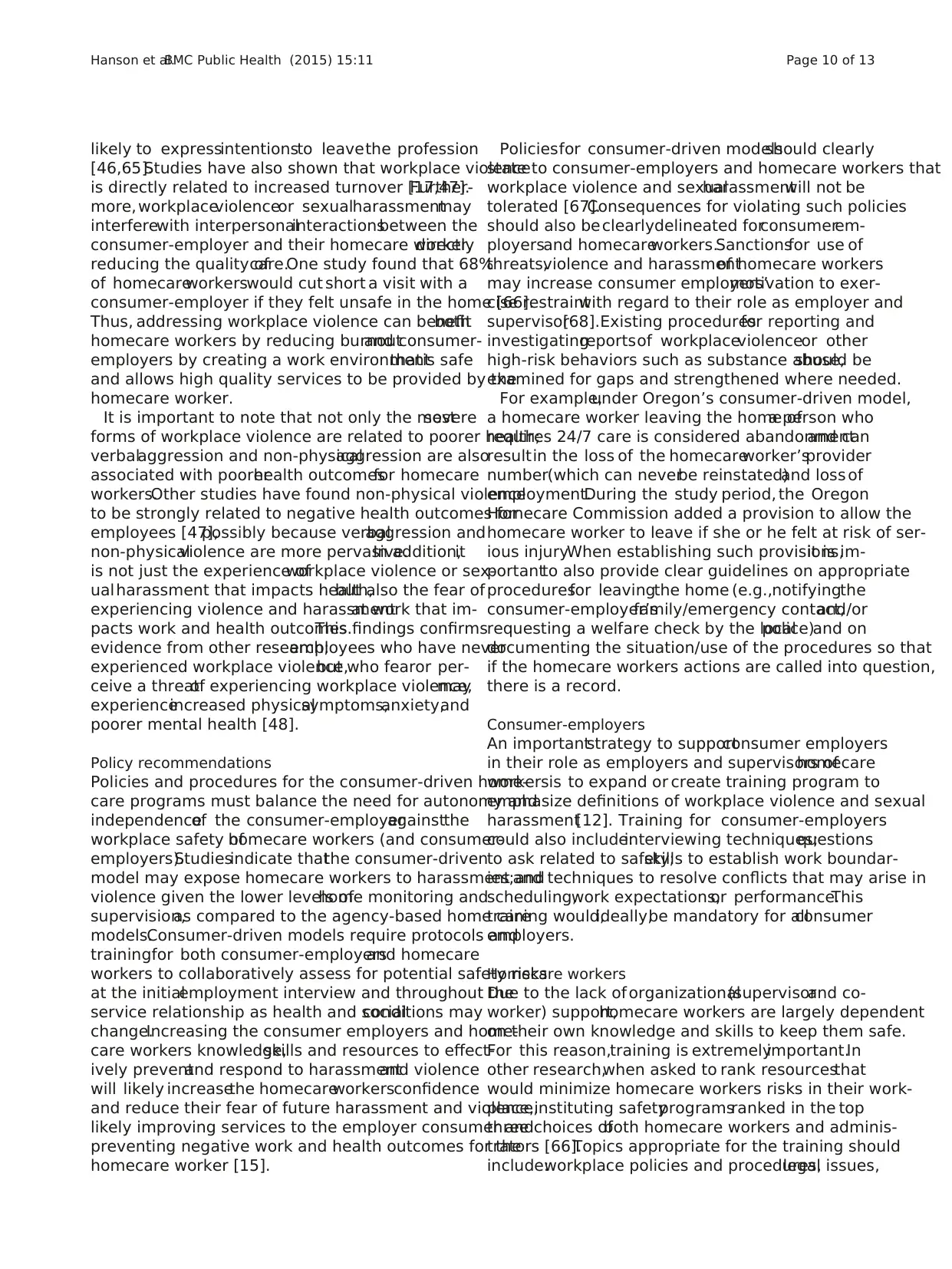

Confidence to prevent and respond to violence and

harassment as a moderator of negative work and health

outcomes

To examine confidence as a moderator ofthe relation-

ship between workplace violence/sexualharassment and

health outcomes,the confidencevariable(mean cen-

tered)and the interaction ofthe confidence with each

workplace violence/sexualharassmentvariable were in-

cluded in ourmultiple regression models.Controlling

for covariates,confidence to prevent and respond to vio-

lence and harassment significantly buffered the effect of

verbalaggression on burnout(B = −5.6,p = .023),and

the effectof workplace aggression on stress(B = −6.5,

p = .016).In other words,having higherconfidence to

prevent and respond to violence and harassment weak-

ened the impactof verbalaggression on burnout,see

Figure 2.In addition,having higher confidence to pre-

vent and respond to violence and harassment weakened

the impact of workplaceaggression on stress,see

Figure 3.None ofthe other interaction terms reached

statistical significance.

Discussion

Key findings

Our findings indicate thathomecare workers,a critical

resource in a consumer-driven modelof health care are

experiencingsubstantiallevelsof workplaceviolence

perpetrated by consumer-employers or other people in

their home.Overall,61.3% offemale homecare workers

in the consumer-driven modelexperienced at least one

type of workplace violence in the past year.Our estimate

of the prevalence of homecare workers experiencing ver-

balaggression (51.5%),workplace aggression (27.5%),or

workplace violence (24.7%),sexualharassment(27.6%)

and sexualaggression (12.8%) in this study is consistent

with,or higher than,those of other studies [7,8,17].The

findings of this study add to the small but growing body

of evidence that workplace violence is a serious occupa-

tional hazard for homecare workers.

Experiencing any form of workplace violence or fear of

violence was associated with negative work and health

outcomes.Specifically,experiencing verbalaggression,

workplace aggression,workplace violence,sexual harass-

ment,sexualaggression,or greater fear was associated

with more work burnout,stress,depression and sleep

problems.Our study provided mixed evidence that con-

fidence in addressing these problems can buffer the im-

pact of workplaceviolenceand sexualharassment.

Sp ecifically,confidence to prevent and respond to vio-

lence and harassmentbuffered the effectof verbalag-

gression on work burnoutand the effectof workplace

aggression on stress.However,in the relationship be-

tween other forms ofworkplace violence/sexualharass-

ment and health outcomes,confidence did not act as a

buffer.

Previousstudiesexaminethe role of personalre-

sources such as confidence as a buffer of the negative ef-

fect of stresson health [60]. Social-learningtheory

suggeststhat fear resultsfrom a lack of self-efficacy

about one’sability to cope with potentiallyharmful

events [61].Research with homecare workers has indi-

cated that fear offuture harassment/violence is a path-

way by which harassment and workplace violence affects

health [6,36].Confidence can play a role in reducing the

autonomic response to fearbefore,during,or aftera

stress-inducing experience [61].If one is confident that

she can prevent,stop, or reducethe severityof the

event,there is little reason to fear it.We did find some

evidence that confidence buffered the effect of verbal ag-

gression on burnout and workplace aggression on stress.

However,we were not able to find evidence that confi-

dence buffered the effectof workplace violence,sexual

Table 3 Multivariable regressions predicting health

outcomes from different forms of workplace aggression

and fear

Unstandardized regression coefficients

Model Burnout Stress Depression Sleep problems

Verbalaggression 18.7 14.5 8.4 14.4

Workplace

aggression

16.2 15.7 11.7 14.8

Workplace violence18.5 15.4 11.8 16.0

Sexualharassment14.6 14.7 9.0 11.7

Sexualviolence 14.4 15.2 8.9 12.5

Fear 7.8 6.9 5.0 5.8

Notes.All regression coefficients were significant at the levelof < .001.The

covariates for burnout were age,education,tenure,hours,and additional jobs.

The covariates for all other models were age and education.The scale for all

health outcomes ranged from 0–100,where high scores indicate poorer health.

Hanson et al.BMC Public Health (2015) 15:11 Page 8 of 13

sion;and 14.4 (p < .001) points higher on sleep problems

than participants who did not experience verbalaggres-

sion.Experiencing any form ofworkplace violence or

sexual harassment was also associated with greater burn-

out controlling forage,education,tenure,hours,and

additional jobs.

Our analyses show that fear of future workplace vio-

lence and sexual harassmentwas associatedwith

worse health outcomesfor homecare workers.Con-

trolling for age and education,for every one-point in-

crease in fear the average score on stress increased 6.9

(p < .001)points; depression increased 5.0 (p < .001)

points; and sleep problemsincreased 5.8(p < .001)

points.For every one-point increase in fear,the aver-

age score on work burnout increased 7.8 (p < .001)

points,controlling forage,education,tenure,hours,

and additional jobs.

Confidence to prevent and respond to violence and

harassment as a moderator of negative work and health

outcomes

To examine confidence as a moderator ofthe relation-

ship between workplace violence/sexualharassment and

health outcomes,the confidencevariable(mean cen-

tered)and the interaction ofthe confidence with each

workplace violence/sexualharassmentvariable were in-

cluded in ourmultiple regression models.Controlling

for covariates,confidence to prevent and respond to vio-

lence and harassment significantly buffered the effect of

verbalaggression on burnout(B = −5.6,p = .023),and

the effectof workplace aggression on stress(B = −6.5,

p = .016).In other words,having higherconfidence to

prevent and respond to violence and harassment weak-

ened the impactof verbalaggression on burnout,see

Figure 2.In addition,having higher confidence to pre-

vent and respond to violence and harassment weakened

the impact of workplaceaggression on stress,see

Figure 3.None ofthe other interaction terms reached

statistical significance.

Discussion

Key findings

Our findings indicate thathomecare workers,a critical

resource in a consumer-driven modelof health care are

experiencingsubstantiallevelsof workplaceviolence

perpetrated by consumer-employers or other people in

their home.Overall,61.3% offemale homecare workers

in the consumer-driven modelexperienced at least one

type of workplace violence in the past year.Our estimate

of the prevalence of homecare workers experiencing ver-

balaggression (51.5%),workplace aggression (27.5%),or

workplace violence (24.7%),sexualharassment(27.6%)

and sexualaggression (12.8%) in this study is consistent

with,or higher than,those of other studies [7,8,17].The

findings of this study add to the small but growing body

of evidence that workplace violence is a serious occupa-

tional hazard for homecare workers.

Experiencing any form of workplace violence or fear of

violence was associated with negative work and health

outcomes.Specifically,experiencing verbalaggression,

workplace aggression,workplace violence,sexual harass-

ment,sexualaggression,or greater fear was associated