Economic Analysis: GDP Determinants and Real Wage Growth in Australia

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/22

|14

|2882

|334

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the determinants of Australia's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 1987/88 to 2017/18, focusing on consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports, both in absolute terms and per capita. The data, sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, reveals trends in these key economic indicators over time. The report also examines the factors contributing to low real wage growth in Australia, including poor productivity, increased inequality, excess capacity in the labor market, declining terms of trade, lower inflationary expectations, and reduced union density. It further illustrates the impact of low wage growth on the aggregate demand of the economy, showing how decreased demand can lead to lower equilibrium output and price levels. The analysis provides insights into the dynamics of the Australian economy and the challenges it faces in achieving sustainable wage growth.

Running head: ECONOMICS

Economics

Name of the student

Name of the university

Author note

Economics

Name of the student

Name of the university

Author note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS

Answer 1

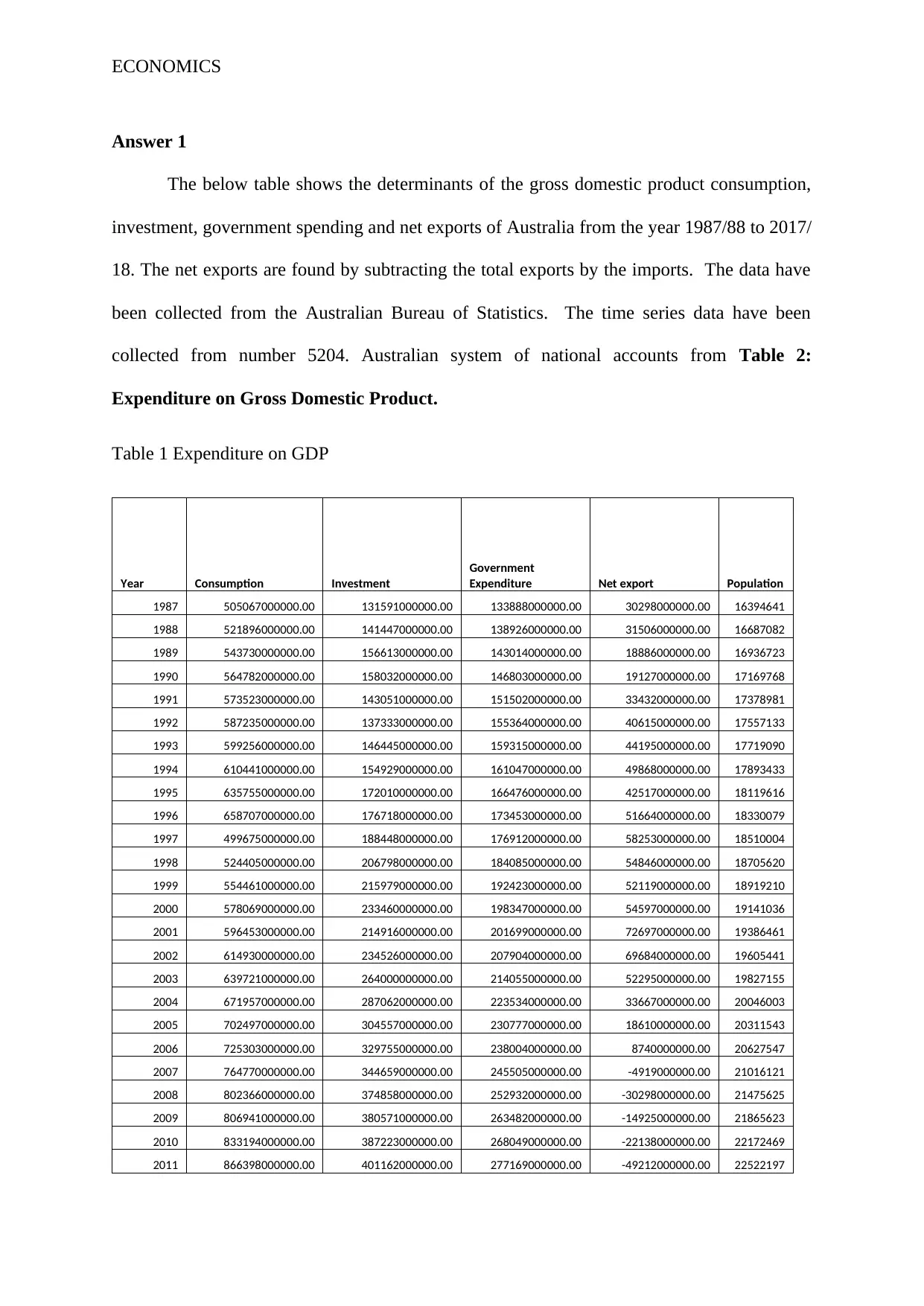

The below table shows the determinants of the gross domestic product consumption,

investment, government spending and net exports of Australia from the year 1987/88 to 2017/

18. The net exports are found by subtracting the total exports by the imports. The data have

been collected from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The time series data have been

collected from number 5204. Australian system of national accounts from Table 2:

Expenditure on Gross Domestic Product.

Table 1 Expenditure on GDP

Year Consumption Investment

Government

Expenditure Net export Population

1987 505067000000.00 131591000000.00 133888000000.00 30298000000.00 16394641

1988 521896000000.00 141447000000.00 138926000000.00 31506000000.00 16687082

1989 543730000000.00 156613000000.00 143014000000.00 18886000000.00 16936723

1990 564782000000.00 158032000000.00 146803000000.00 19127000000.00 17169768

1991 573523000000.00 143051000000.00 151502000000.00 33432000000.00 17378981

1992 587235000000.00 137333000000.00 155364000000.00 40615000000.00 17557133

1993 599256000000.00 146445000000.00 159315000000.00 44195000000.00 17719090

1994 610441000000.00 154929000000.00 161047000000.00 49868000000.00 17893433

1995 635755000000.00 172010000000.00 166476000000.00 42517000000.00 18119616

1996 658707000000.00 176718000000.00 173453000000.00 51664000000.00 18330079

1997 499675000000.00 188448000000.00 176912000000.00 58253000000.00 18510004

1998 524405000000.00 206798000000.00 184085000000.00 54846000000.00 18705620

1999 554461000000.00 215979000000.00 192423000000.00 52119000000.00 18919210

2000 578069000000.00 233460000000.00 198347000000.00 54597000000.00 19141036

2001 596453000000.00 214916000000.00 201699000000.00 72697000000.00 19386461

2002 614930000000.00 234526000000.00 207904000000.00 69684000000.00 19605441

2003 639721000000.00 264000000000.00 214055000000.00 52295000000.00 19827155

2004 671957000000.00 287062000000.00 223534000000.00 33667000000.00 20046003

2005 702497000000.00 304557000000.00 230777000000.00 18610000000.00 20311543

2006 725303000000.00 329755000000.00 238004000000.00 8740000000.00 20627547

2007 764770000000.00 344659000000.00 245505000000.00 -4919000000.00 21016121

2008 802366000000.00 374858000000.00 252932000000.00 -30298000000.00 21475625

2009 806941000000.00 380571000000.00 263482000000.00 -14925000000.00 21865623

2010 833194000000.00 387223000000.00 268049000000.00 -22138000000.00 22172469

2011 866398000000.00 401162000000.00 277169000000.00 -49212000000.00 22522197

Answer 1

The below table shows the determinants of the gross domestic product consumption,

investment, government spending and net exports of Australia from the year 1987/88 to 2017/

18. The net exports are found by subtracting the total exports by the imports. The data have

been collected from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The time series data have been

collected from number 5204. Australian system of national accounts from Table 2:

Expenditure on Gross Domestic Product.

Table 1 Expenditure on GDP

Year Consumption Investment

Government

Expenditure Net export Population

1987 505067000000.00 131591000000.00 133888000000.00 30298000000.00 16394641

1988 521896000000.00 141447000000.00 138926000000.00 31506000000.00 16687082

1989 543730000000.00 156613000000.00 143014000000.00 18886000000.00 16936723

1990 564782000000.00 158032000000.00 146803000000.00 19127000000.00 17169768

1991 573523000000.00 143051000000.00 151502000000.00 33432000000.00 17378981

1992 587235000000.00 137333000000.00 155364000000.00 40615000000.00 17557133

1993 599256000000.00 146445000000.00 159315000000.00 44195000000.00 17719090

1994 610441000000.00 154929000000.00 161047000000.00 49868000000.00 17893433

1995 635755000000.00 172010000000.00 166476000000.00 42517000000.00 18119616

1996 658707000000.00 176718000000.00 173453000000.00 51664000000.00 18330079

1997 499675000000.00 188448000000.00 176912000000.00 58253000000.00 18510004

1998 524405000000.00 206798000000.00 184085000000.00 54846000000.00 18705620

1999 554461000000.00 215979000000.00 192423000000.00 52119000000.00 18919210

2000 578069000000.00 233460000000.00 198347000000.00 54597000000.00 19141036

2001 596453000000.00 214916000000.00 201699000000.00 72697000000.00 19386461

2002 614930000000.00 234526000000.00 207904000000.00 69684000000.00 19605441

2003 639721000000.00 264000000000.00 214055000000.00 52295000000.00 19827155

2004 671957000000.00 287062000000.00 223534000000.00 33667000000.00 20046003

2005 702497000000.00 304557000000.00 230777000000.00 18610000000.00 20311543

2006 725303000000.00 329755000000.00 238004000000.00 8740000000.00 20627547

2007 764770000000.00 344659000000.00 245505000000.00 -4919000000.00 21016121

2008 802366000000.00 374858000000.00 252932000000.00 -30298000000.00 21475625

2009 806941000000.00 380571000000.00 263482000000.00 -14925000000.00 21865623

2010 833194000000.00 387223000000.00 268049000000.00 -22138000000.00 22172469

2011 866398000000.00 401162000000.00 277169000000.00 -49212000000.00 22522197

ECONOMICS

2012 892157000000.00 447442000000.00 287291000000.00 -72775000000.00 22928023

2013 907941000000.00 460882000000.00 288131000000.00 -58985000000.00 23297777

2014 930082000000.00 452765000000.00 292564000000.00 -33338000000.00 23640331

2015 951908000000.00 438441000000.00 299666000000.00 -15450000000.00 23984581

2016 978114000000.00 423372000000.00 312459000000.00 7654000000.00 24389684

2017 1001197000000.00 422428000000.00 328092000000.00 10851000000.00 24775564

2018 1029816000000.00 440890000000.00 340929000000.00 -568000000.00 25101917

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government. 2019).

2012 892157000000.00 447442000000.00 287291000000.00 -72775000000.00 22928023

2013 907941000000.00 460882000000.00 288131000000.00 -58985000000.00 23297777

2014 930082000000.00 452765000000.00 292564000000.00 -33338000000.00 23640331

2015 951908000000.00 438441000000.00 299666000000.00 -15450000000.00 23984581

2016 978114000000.00 423372000000.00 312459000000.00 7654000000.00 24389684

2017 1001197000000.00 422428000000.00 328092000000.00 10851000000.00 24775564

2018 1029816000000.00 440890000000.00 340929000000.00 -568000000.00 25101917

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government. 2019).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECONOMICS

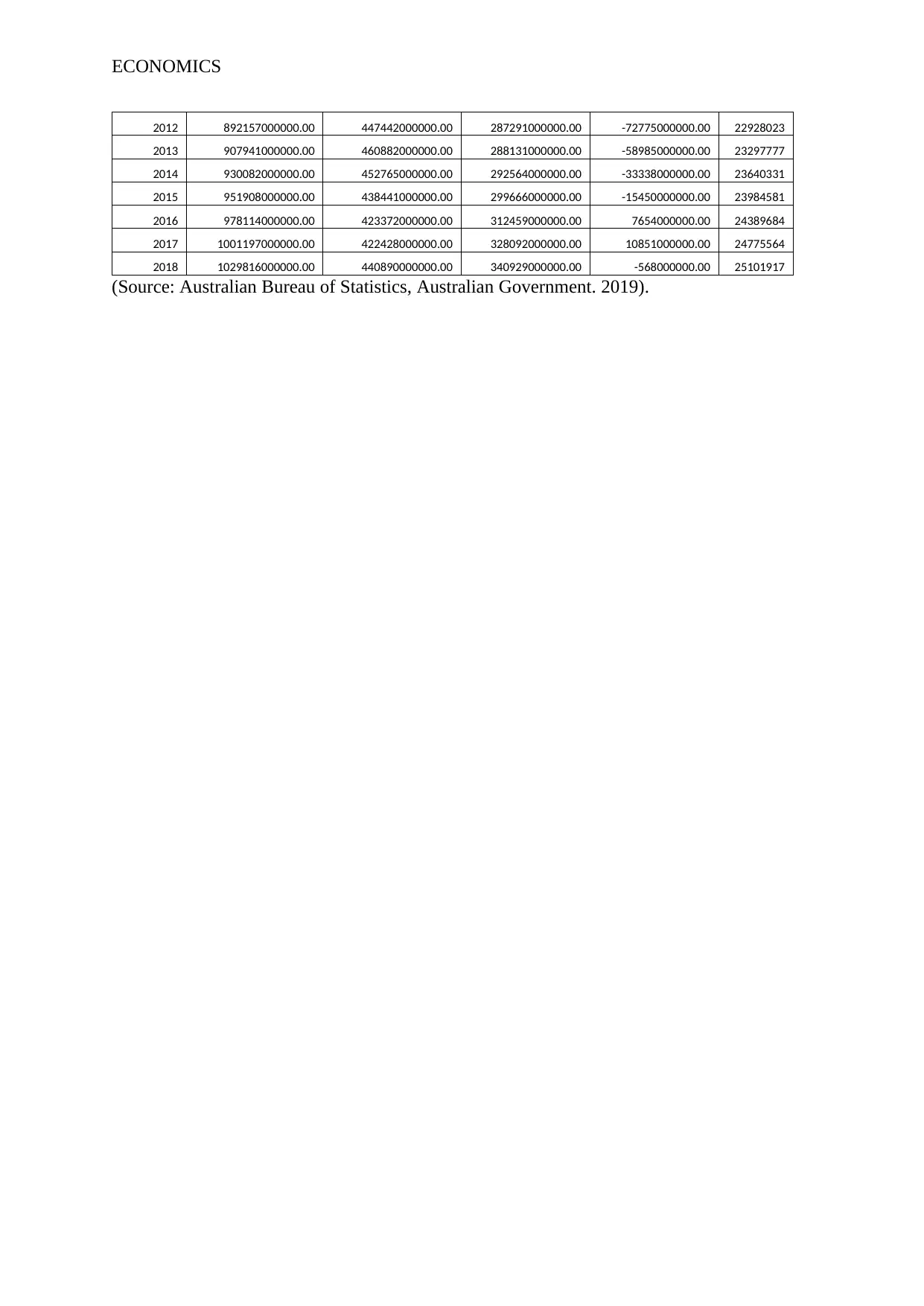

However, the first part of the question states to find the determinants of the gross

domestic product in terms of per capita which means each of the determinants are divided by

the total population. When each of the values are divided by the total population, the

consumption, investment, government spending and net exports per capita are found.

Table 2: Determinants of GDP per capita

Year

Consumpti

on

Investmen

t

Governme

nt

Expenditur

e Net export

1987

30806.8

3

8026.46

4

8166.57

1

1848.04

3

1988

31275.4

5

8476.43

7

8325.36

2

1888.04

7

1989

32103.6

1

9246.94

8

8444.01

8

1115.09

2

1990

32893.9

8

9204.08

5

8550.08

6

1113.99

3

1991

33000.9

6

8231.26

5

8717.54

2

1923.70

3

1992

33447.0

9

7822.06

3

8849.05

3

2313.30

5

1993 33819.8

8264.81

5 8991.15

2494.20

3

1994

34115.3

7

8658.42

8

9000.34

1

2786.94

4

1995

35086.5

6

9493.02

7

9187.61

2

2346.46

3

1996

35935.8

5

9640.87

5

9462.75

2

2818.53

7

1997

26994.8

6

10180.8

7

9557.64

2

3147.10

9

1998

28034.6

2

11055.3

9 9841.16 2932.06

1999

29306.7

7

11415.8

6

10170.7

7

2754.81

9

2000

30200.5

1

12196.8

3 10362.4

2852.35

3

2001

30766.4

7

11085.8

8

10404.1

2

3749.88

5

2002

31365.2

7

11962.2

9 10604.4

3554.31

9

2003

32264.8

9

13315.0

7

10796.0

5

2637.54

4

2004

33520.7

5

14320.1

6

11151.0

5

1679.48

7

However, the first part of the question states to find the determinants of the gross

domestic product in terms of per capita which means each of the determinants are divided by

the total population. When each of the values are divided by the total population, the

consumption, investment, government spending and net exports per capita are found.

Table 2: Determinants of GDP per capita

Year

Consumpti

on

Investmen

t

Governme

nt

Expenditur

e Net export

1987

30806.8

3

8026.46

4

8166.57

1

1848.04

3

1988

31275.4

5

8476.43

7

8325.36

2

1888.04

7

1989

32103.6

1

9246.94

8

8444.01

8

1115.09

2

1990

32893.9

8

9204.08

5

8550.08

6

1113.99

3

1991

33000.9

6

8231.26

5

8717.54

2

1923.70

3

1992

33447.0

9

7822.06

3

8849.05

3

2313.30

5

1993 33819.8

8264.81

5 8991.15

2494.20

3

1994

34115.3

7

8658.42

8

9000.34

1

2786.94

4

1995

35086.5

6

9493.02

7

9187.61

2

2346.46

3

1996

35935.8

5

9640.87

5

9462.75

2

2818.53

7

1997

26994.8

6

10180.8

7

9557.64

2

3147.10

9

1998

28034.6

2

11055.3

9 9841.16 2932.06

1999

29306.7

7

11415.8

6

10170.7

7

2754.81

9

2000

30200.5

1

12196.8

3 10362.4

2852.35

3

2001

30766.4

7

11085.8

8

10404.1

2

3749.88

5

2002

31365.2

7

11962.2

9 10604.4

3554.31

9

2003

32264.8

9

13315.0

7

10796.0

5

2637.54

4

2004

33520.7

5

14320.1

6

11151.0

5

1679.48

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS

2005 34586.1

14994.2

8

11361.8

6

916.227

8

2006

35161.8

6

15986.1

5

11538.1

6

423.705

3

2007

36389.6

8

16399.7

4

11681.7

5

-

234.058

2008

37361.7

1

17455.0

4

11777.6

3

-

1410.81

2009

36904.5

5

17404.9

9

12050.0

6

-

682.578

2010

37577.8

6

17464.1

4

12089.2

7

-

998.445

2011

38468.6

3

17811.8

5

12306.4

8

-

2185.04

2012 38911.2

19515.0

7

12530.1

3

-

3174.06

2013

38971.1

4

19782.2

3

12367.3

2

-

2531.79

2014

39343.0

2

19152.2

3

12375.6

3

-

1410.22

2015

39688.3

3

18280.1

2

12494.1

1

-

644.164

2016

40103.5

9

17358.6

5

12811.1

1

313.821

2

2017

40410.6

6

17050.1

9

13242.5

6

437.971

9

2018

41025.3

9 17564

13581.7

9

-

22.6278

2005 34586.1

14994.2

8

11361.8

6

916.227

8

2006

35161.8

6

15986.1

5

11538.1

6

423.705

3

2007

36389.6

8

16399.7

4

11681.7

5

-

234.058

2008

37361.7

1

17455.0

4

11777.6

3

-

1410.81

2009

36904.5

5

17404.9

9

12050.0

6

-

682.578

2010

37577.8

6

17464.1

4

12089.2

7

-

998.445

2011

38468.6

3

17811.8

5

12306.4

8

-

2185.04

2012 38911.2

19515.0

7

12530.1

3

-

3174.06

2013

38971.1

4

19782.2

3

12367.3

2

-

2531.79

2014

39343.0

2

19152.2

3

12375.6

3

-

1410.22

2015

39688.3

3

18280.1

2

12494.1

1

-

644.164

2016

40103.5

9

17358.6

5

12811.1

1

313.821

2

2017

40410.6

6

17050.1

9

13242.5

6

437.971

9

2018

41025.3

9 17564

13581.7

9

-

22.6278

ECONOMICS

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

30000

35000

40000

45000

Consumption

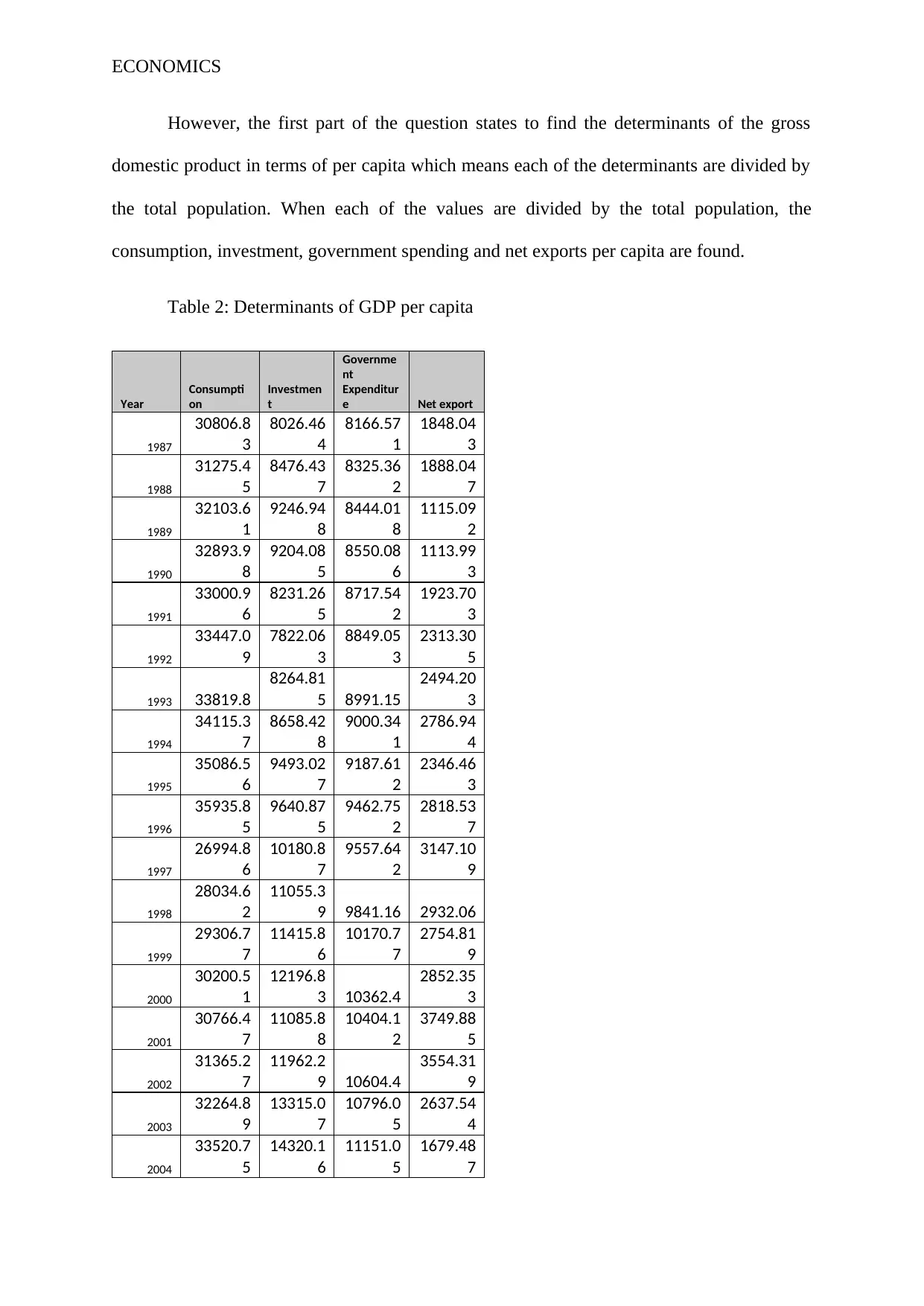

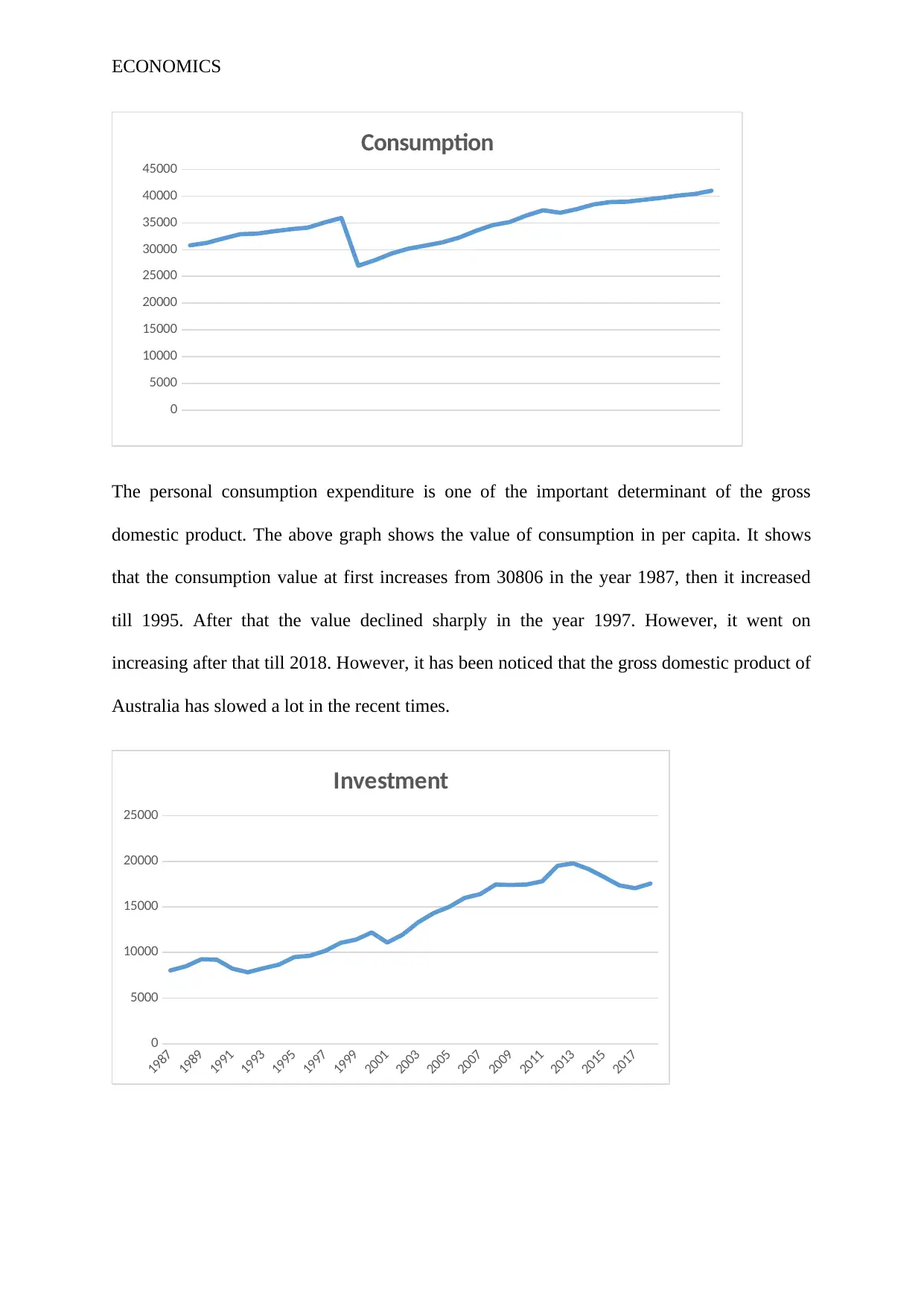

The personal consumption expenditure is one of the important determinant of the gross

domestic product. The above graph shows the value of consumption in per capita. It shows

that the consumption value at first increases from 30806 in the year 1987, then it increased

till 1995. After that the value declined sharply in the year 1997. However, it went on

increasing after that till 2018. However, it has been noticed that the gross domestic product of

Australia has slowed a lot in the recent times.

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

Investment

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

30000

35000

40000

45000

Consumption

The personal consumption expenditure is one of the important determinant of the gross

domestic product. The above graph shows the value of consumption in per capita. It shows

that the consumption value at first increases from 30806 in the year 1987, then it increased

till 1995. After that the value declined sharply in the year 1997. However, it went on

increasing after that till 2018. However, it has been noticed that the gross domestic product of

Australia has slowed a lot in the recent times.

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

Investment

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECONOMICS

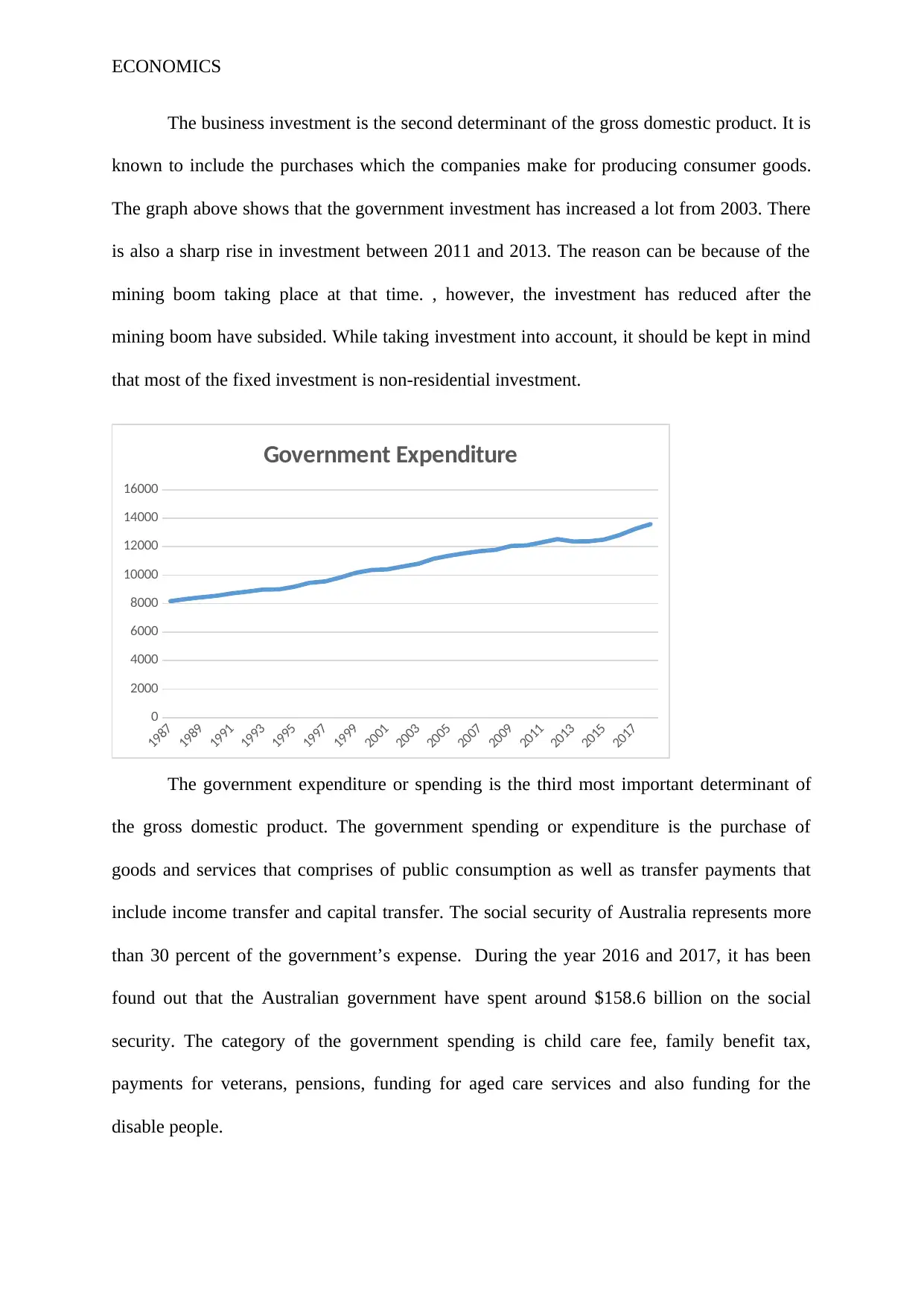

The business investment is the second determinant of the gross domestic product. It is

known to include the purchases which the companies make for producing consumer goods.

The graph above shows that the government investment has increased a lot from 2003. There

is also a sharp rise in investment between 2011 and 2013. The reason can be because of the

mining boom taking place at that time. , however, the investment has reduced after the

mining boom have subsided. While taking investment into account, it should be kept in mind

that most of the fixed investment is non-residential investment.

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

Government Expenditure

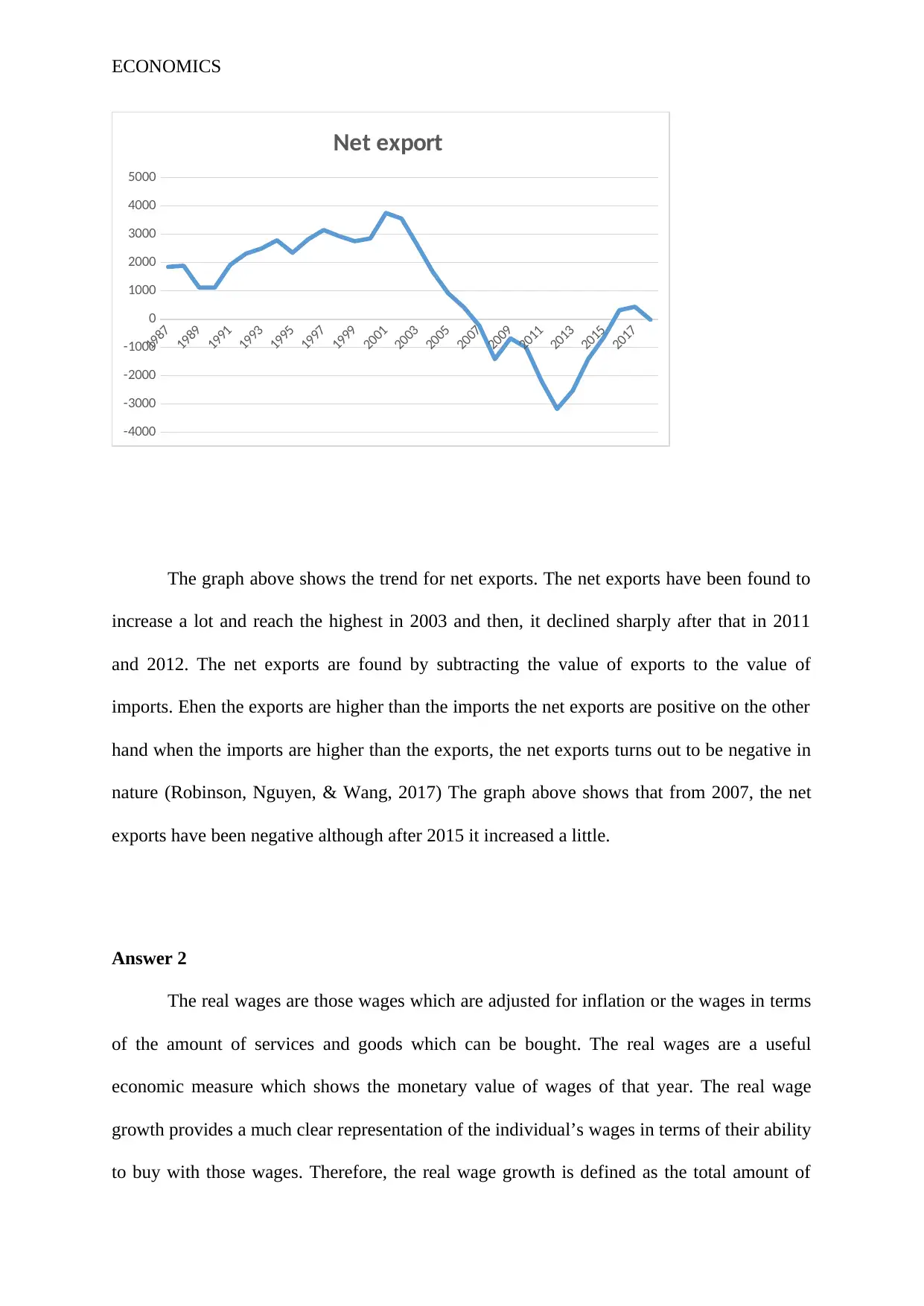

The government expenditure or spending is the third most important determinant of

the gross domestic product. The government spending or expenditure is the purchase of

goods and services that comprises of public consumption as well as transfer payments that

include income transfer and capital transfer. The social security of Australia represents more

than 30 percent of the government’s expense. During the year 2016 and 2017, it has been

found out that the Australian government have spent around $158.6 billion on the social

security. The category of the government spending is child care fee, family benefit tax,

payments for veterans, pensions, funding for aged care services and also funding for the

disable people.

The business investment is the second determinant of the gross domestic product. It is

known to include the purchases which the companies make for producing consumer goods.

The graph above shows that the government investment has increased a lot from 2003. There

is also a sharp rise in investment between 2011 and 2013. The reason can be because of the

mining boom taking place at that time. , however, the investment has reduced after the

mining boom have subsided. While taking investment into account, it should be kept in mind

that most of the fixed investment is non-residential investment.

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

Government Expenditure

The government expenditure or spending is the third most important determinant of

the gross domestic product. The government spending or expenditure is the purchase of

goods and services that comprises of public consumption as well as transfer payments that

include income transfer and capital transfer. The social security of Australia represents more

than 30 percent of the government’s expense. During the year 2016 and 2017, it has been

found out that the Australian government have spent around $158.6 billion on the social

security. The category of the government spending is child care fee, family benefit tax,

payments for veterans, pensions, funding for aged care services and also funding for the

disable people.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

-4000

-3000

-2000

-1000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Net export

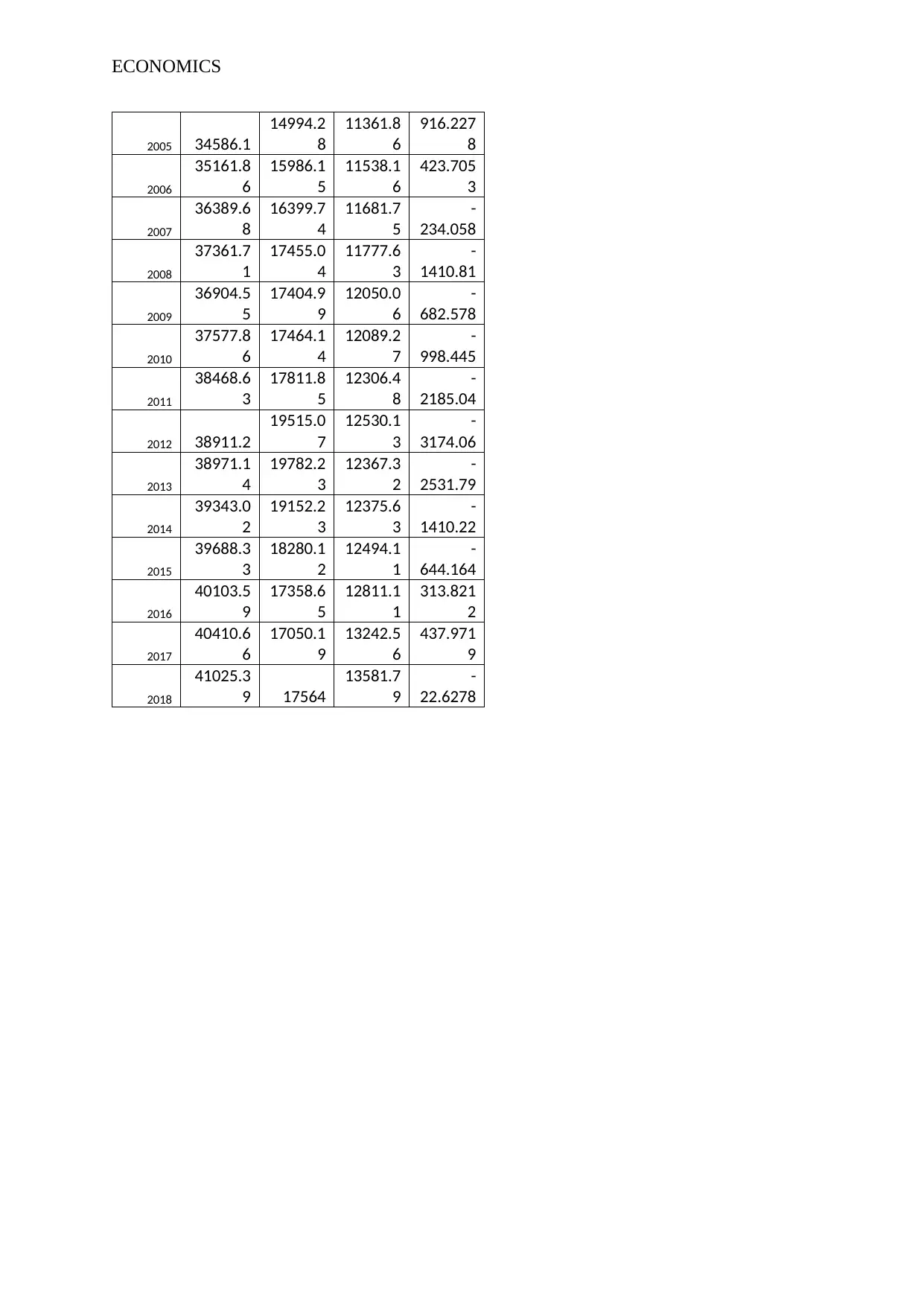

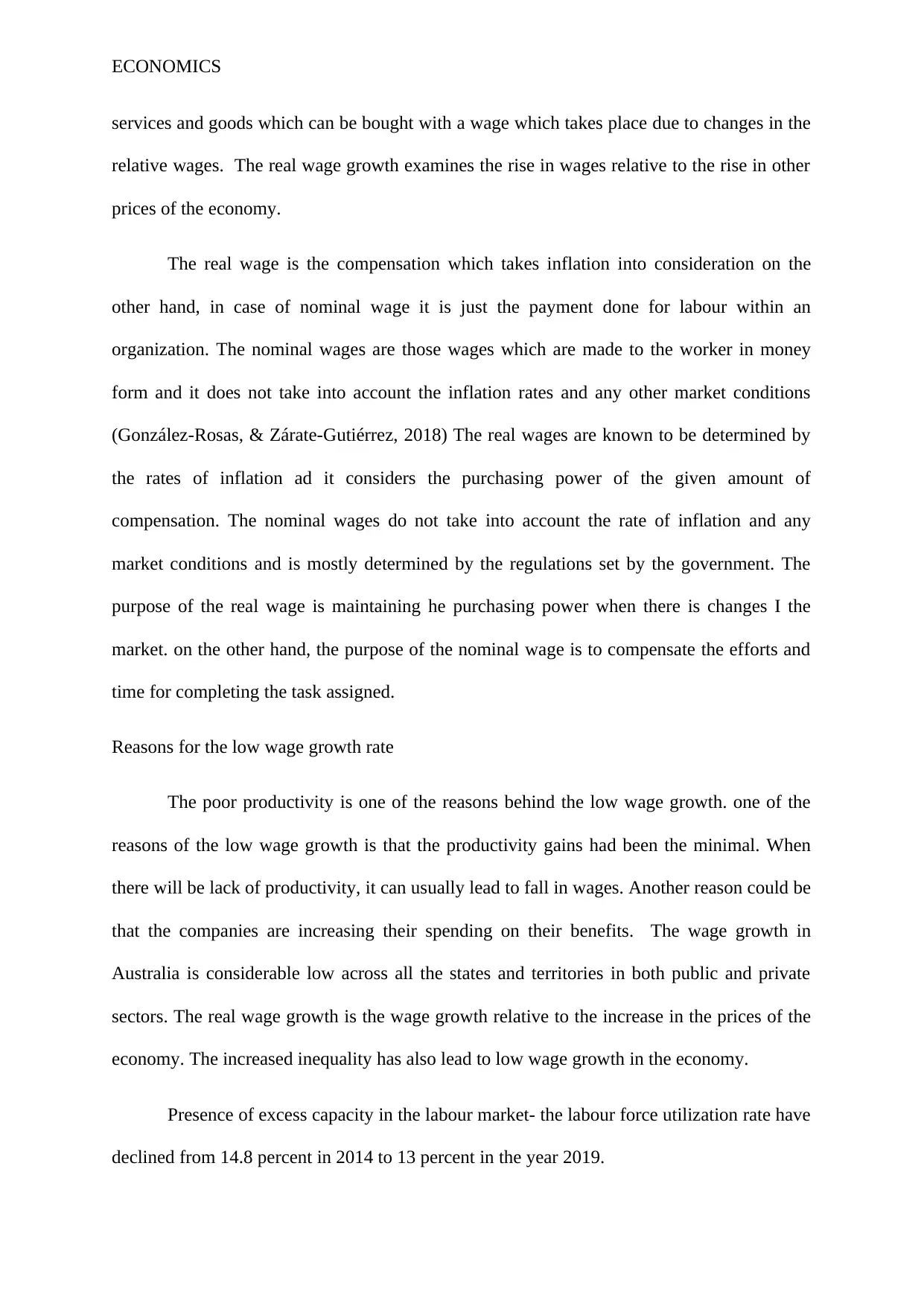

The graph above shows the trend for net exports. The net exports have been found to

increase a lot and reach the highest in 2003 and then, it declined sharply after that in 2011

and 2012. The net exports are found by subtracting the value of exports to the value of

imports. Ehen the exports are higher than the imports the net exports are positive on the other

hand when the imports are higher than the exports, the net exports turns out to be negative in

nature (Robinson, Nguyen, & Wang, 2017) The graph above shows that from 2007, the net

exports have been negative although after 2015 it increased a little.

Answer 2

The real wages are those wages which are adjusted for inflation or the wages in terms

of the amount of services and goods which can be bought. The real wages are a useful

economic measure which shows the monetary value of wages of that year. The real wage

growth provides a much clear representation of the individual’s wages in terms of their ability

to buy with those wages. Therefore, the real wage growth is defined as the total amount of

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

-4000

-3000

-2000

-1000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Net export

The graph above shows the trend for net exports. The net exports have been found to

increase a lot and reach the highest in 2003 and then, it declined sharply after that in 2011

and 2012. The net exports are found by subtracting the value of exports to the value of

imports. Ehen the exports are higher than the imports the net exports are positive on the other

hand when the imports are higher than the exports, the net exports turns out to be negative in

nature (Robinson, Nguyen, & Wang, 2017) The graph above shows that from 2007, the net

exports have been negative although after 2015 it increased a little.

Answer 2

The real wages are those wages which are adjusted for inflation or the wages in terms

of the amount of services and goods which can be bought. The real wages are a useful

economic measure which shows the monetary value of wages of that year. The real wage

growth provides a much clear representation of the individual’s wages in terms of their ability

to buy with those wages. Therefore, the real wage growth is defined as the total amount of

ECONOMICS

services and goods which can be bought with a wage which takes place due to changes in the

relative wages. The real wage growth examines the rise in wages relative to the rise in other

prices of the economy.

The real wage is the compensation which takes inflation into consideration on the

other hand, in case of nominal wage it is just the payment done for labour within an

organization. The nominal wages are those wages which are made to the worker in money

form and it does not take into account the inflation rates and any other market conditions

(González-Rosas, & Zárate-Gutiérrez, 2018) The real wages are known to be determined by

the rates of inflation ad it considers the purchasing power of the given amount of

compensation. The nominal wages do not take into account the rate of inflation and any

market conditions and is mostly determined by the regulations set by the government. The

purpose of the real wage is maintaining he purchasing power when there is changes I the

market. on the other hand, the purpose of the nominal wage is to compensate the efforts and

time for completing the task assigned.

Reasons for the low wage growth rate

The poor productivity is one of the reasons behind the low wage growth. one of the

reasons of the low wage growth is that the productivity gains had been the minimal. When

there will be lack of productivity, it can usually lead to fall in wages. Another reason could be

that the companies are increasing their spending on their benefits. The wage growth in

Australia is considerable low across all the states and territories in both public and private

sectors. The real wage growth is the wage growth relative to the increase in the prices of the

economy. The increased inequality has also lead to low wage growth in the economy.

Presence of excess capacity in the labour market- the labour force utilization rate have

declined from 14.8 percent in 2014 to 13 percent in the year 2019.

services and goods which can be bought with a wage which takes place due to changes in the

relative wages. The real wage growth examines the rise in wages relative to the rise in other

prices of the economy.

The real wage is the compensation which takes inflation into consideration on the

other hand, in case of nominal wage it is just the payment done for labour within an

organization. The nominal wages are those wages which are made to the worker in money

form and it does not take into account the inflation rates and any other market conditions

(González-Rosas, & Zárate-Gutiérrez, 2018) The real wages are known to be determined by

the rates of inflation ad it considers the purchasing power of the given amount of

compensation. The nominal wages do not take into account the rate of inflation and any

market conditions and is mostly determined by the regulations set by the government. The

purpose of the real wage is maintaining he purchasing power when there is changes I the

market. on the other hand, the purpose of the nominal wage is to compensate the efforts and

time for completing the task assigned.

Reasons for the low wage growth rate

The poor productivity is one of the reasons behind the low wage growth. one of the

reasons of the low wage growth is that the productivity gains had been the minimal. When

there will be lack of productivity, it can usually lead to fall in wages. Another reason could be

that the companies are increasing their spending on their benefits. The wage growth in

Australia is considerable low across all the states and territories in both public and private

sectors. The real wage growth is the wage growth relative to the increase in the prices of the

economy. The increased inequality has also lead to low wage growth in the economy.

Presence of excess capacity in the labour market- the labour force utilization rate have

declined from 14.8 percent in 2014 to 13 percent in the year 2019.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECONOMICS

Decline in the terms of trade

Most of the firms in Australia have been providing higher wages during the term

when the terms of trade have been more favourable in nature that was between 2008 to 2011.

When the terms of trade had been high it contributed to higher output prices for the firms

specially in case of mining companies. As the mining boom subsided., the terms of trade

declined by 35 percent. Though the terms of trade have recovered during 2016, there had

been only a moderate increase in the wage growth.

Declining inflationary expectations

Another reason behind the low wage growth is decline in the inflationary expectation. The

expectation for the inflation rate for the unions and market economists have been below 3

percent since 2012 (Arsov, & Evans, 2018). The actual inflation rates had been had been

below expectation for many years. the expectation of inflation is taken into account by both

the employers as well as by the unions when considering the increase in wage in the process

of negotiation.

Decline in the union density

Another factor which leads to the lower wage growth is the decline in the bargaining

power of workers. The bargaining power of the employees are affected by the steady decline

in the union membership. It has been found out that the union density in Australia have

declined over a long term from 41 percent to 13 percent in 2018. The slowdown of the

collective bargaining process in both the public and private sectors led to low wage growth in

Australia. It has also been found out that the wage levels are quite higher in the capital cities

compared to the regional areas.

Decline in the terms of trade

Most of the firms in Australia have been providing higher wages during the term

when the terms of trade have been more favourable in nature that was between 2008 to 2011.

When the terms of trade had been high it contributed to higher output prices for the firms

specially in case of mining companies. As the mining boom subsided., the terms of trade

declined by 35 percent. Though the terms of trade have recovered during 2016, there had

been only a moderate increase in the wage growth.

Declining inflationary expectations

Another reason behind the low wage growth is decline in the inflationary expectation. The

expectation for the inflation rate for the unions and market economists have been below 3

percent since 2012 (Arsov, & Evans, 2018). The actual inflation rates had been had been

below expectation for many years. the expectation of inflation is taken into account by both

the employers as well as by the unions when considering the increase in wage in the process

of negotiation.

Decline in the union density

Another factor which leads to the lower wage growth is the decline in the bargaining

power of workers. The bargaining power of the employees are affected by the steady decline

in the union membership. It has been found out that the union density in Australia have

declined over a long term from 41 percent to 13 percent in 2018. The slowdown of the

collective bargaining process in both the public and private sectors led to low wage growth in

Australia. It has also been found out that the wage levels are quite higher in the capital cities

compared to the regional areas.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS

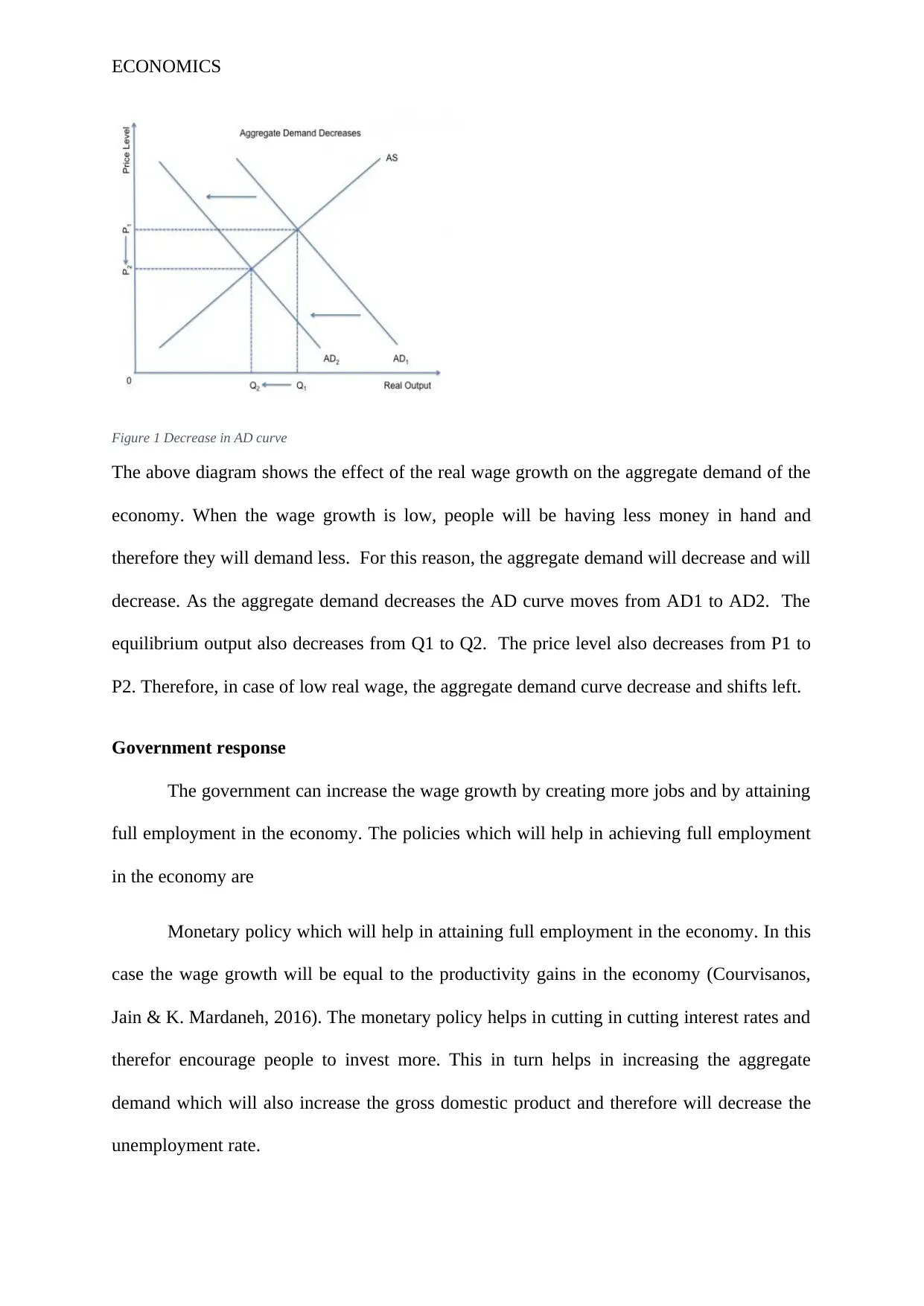

Figure 1 Decrease in AD curve

The above diagram shows the effect of the real wage growth on the aggregate demand of the

economy. When the wage growth is low, people will be having less money in hand and

therefore they will demand less. For this reason, the aggregate demand will decrease and will

decrease. As the aggregate demand decreases the AD curve moves from AD1 to AD2. The

equilibrium output also decreases from Q1 to Q2. The price level also decreases from P1 to

P2. Therefore, in case of low real wage, the aggregate demand curve decrease and shifts left.

Government response

The government can increase the wage growth by creating more jobs and by attaining

full employment in the economy. The policies which will help in achieving full employment

in the economy are

Monetary policy which will help in attaining full employment in the economy. In this

case the wage growth will be equal to the productivity gains in the economy (Courvisanos,

Jain & K. Mardaneh, 2016). The monetary policy helps in cutting in cutting interest rates and

therefor encourage people to invest more. This in turn helps in increasing the aggregate

demand which will also increase the gross domestic product and therefore will decrease the

unemployment rate.

Figure 1 Decrease in AD curve

The above diagram shows the effect of the real wage growth on the aggregate demand of the

economy. When the wage growth is low, people will be having less money in hand and

therefore they will demand less. For this reason, the aggregate demand will decrease and will

decrease. As the aggregate demand decreases the AD curve moves from AD1 to AD2. The

equilibrium output also decreases from Q1 to Q2. The price level also decreases from P1 to

P2. Therefore, in case of low real wage, the aggregate demand curve decrease and shifts left.

Government response

The government can increase the wage growth by creating more jobs and by attaining

full employment in the economy. The policies which will help in achieving full employment

in the economy are

Monetary policy which will help in attaining full employment in the economy. In this

case the wage growth will be equal to the productivity gains in the economy (Courvisanos,

Jain & K. Mardaneh, 2016). The monetary policy helps in cutting in cutting interest rates and

therefor encourage people to invest more. This in turn helps in increasing the aggregate

demand which will also increase the gross domestic product and therefore will decrease the

unemployment rate.

ECONOMICS

The policymakers can help in growing wages by increasing the minimum wage,

updating the overtime rules and by strengthening rights to collective bargaining.

The government should spend in public investment and infrastructure for attaining higher

wages. The policymakers should also reduce trade deficit for increasing the jobs in the

economy. Undertaking a sustained program for the public investment will create jobs and

also increase the growth and productivity.

The policymakers can help in growing wages by increasing the minimum wage,

updating the overtime rules and by strengthening rights to collective bargaining.

The government should spend in public investment and infrastructure for attaining higher

wages. The policymakers should also reduce trade deficit for increasing the jobs in the

economy. Undertaking a sustained program for the public investment will create jobs and

also increase the growth and productivity.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.