(PDF) Anxiety disorders in older adults

VerifiedAdded on 2021/06/17

|34

|9370

|58

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

CHAPTER TWO 1

Difference in Non-Clinical Anxiety Levels between Young and Older Adults and in

Respect to Depression, Cognitive Functions and Demographic Parameters

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Keywords: Non-Clinical Anxiety, Depression, Subjective memory function, and Objective

Cognitive Function, Demographic Parameters, Younger adults, Older adults.

Difference in Non-Clinical Anxiety Levels between Young and Older Adults and in

Respect to Depression, Cognitive Functions and Demographic Parameters

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Keywords: Non-Clinical Anxiety, Depression, Subjective memory function, and Objective

Cognitive Function, Demographic Parameters, Younger adults, Older adults.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER TWO 2

ABSTRACT

Relationship between anxiety levels and speed of information processing in young and older

adults has hardly been researched on, in relation to the plethora of brain functions that

encompass attention and other cognitive functions. This research taps into this gap,

evaluating the relationship between subclinical anxiety, cognitive functions and demographic

factors.

Methods used in data collection include Progressive Retrogressive Memory Questionnaire

(PRMQ), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), State and Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Trait and Anxiety Inventory (TAI) and Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MoCA). The results obtained from these methods were closely related,

confirming their reliability.

Older group was found to be less susceptible to different subclinical anxiety levels and its

effects than the younger group; inhibitory cognitive control is better managed by the older

group than the younger group. Demographic factors do not cause much non-clinical anxiety

as is seen in the results section.

ABSTRACT

Relationship between anxiety levels and speed of information processing in young and older

adults has hardly been researched on, in relation to the plethora of brain functions that

encompass attention and other cognitive functions. This research taps into this gap,

evaluating the relationship between subclinical anxiety, cognitive functions and demographic

factors.

Methods used in data collection include Progressive Retrogressive Memory Questionnaire

(PRMQ), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), State and Trait

Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Trait and Anxiety Inventory (TAI) and Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (MoCA). The results obtained from these methods were closely related,

confirming their reliability.

Older group was found to be less susceptible to different subclinical anxiety levels and its

effects than the younger group; inhibitory cognitive control is better managed by the older

group than the younger group. Demographic factors do not cause much non-clinical anxiety

as is seen in the results section.

CHAPTER TWO 3

INTRODUCTION

This study aims at examining the difference in subclinical anxiety levels between young and

older adults in relation to depression, subjective memory function, objective cognitive

function and demographic factors, that isare, age, gender, years of education, handedness,

eyesight which are not extensively iterated in previous studies is also examined. . etc. we

also need to say, why it is important to look at all those terms and see the correlation between

them, before start looking at attention and information processing speed deeply. Does that

provide you a sign or and evidence re. non-clinical anxiety influences or something?The

primary objective of this research is to evaluate the existing association between the speed of

information processing and non-clinical anxiety levels, among older and younger adults, in

relation to plethora of brain functions that encompass attention. These functions are generally

related to visual attention, selective attention, inhibitory cognitive control, reaction time (RT)

and intra-individual reactive time (IIRT).

The research also aims to determine the relationship between the aforementioned non-clinical

anxiety levels and cognitive function, both subjective and objective, quality of sleep and

demographics such as age, gender, handedness, education levels or attainment and vision of

the participants.

Depression and anxiety disorders are linked with abnormal cognitive control in the form of an

attentional bias towards negative information and reduced inhibitory control (Cisler &

Koster, 2010). Even though there is a high rate for comorbidity of the anxiety disorders and

depression, above 75%, they have various underlying neural correlates. The high comorbidity

implies commonality in etiology (Peckham, McHugh & Otto, 2010). The dorsal anterior

cingulate cortex is involved in inhibitory cognitive control. It detects conflict between

INTRODUCTION

This study aims at examining the difference in subclinical anxiety levels between young and

older adults in relation to depression, subjective memory function, objective cognitive

function and demographic factors, that isare, age, gender, years of education, handedness,

eyesight which are not extensively iterated in previous studies is also examined. . etc. we

also need to say, why it is important to look at all those terms and see the correlation between

them, before start looking at attention and information processing speed deeply. Does that

provide you a sign or and evidence re. non-clinical anxiety influences or something?The

primary objective of this research is to evaluate the existing association between the speed of

information processing and non-clinical anxiety levels, among older and younger adults, in

relation to plethora of brain functions that encompass attention. These functions are generally

related to visual attention, selective attention, inhibitory cognitive control, reaction time (RT)

and intra-individual reactive time (IIRT).

The research also aims to determine the relationship between the aforementioned non-clinical

anxiety levels and cognitive function, both subjective and objective, quality of sleep and

demographics such as age, gender, handedness, education levels or attainment and vision of

the participants.

Depression and anxiety disorders are linked with abnormal cognitive control in the form of an

attentional bias towards negative information and reduced inhibitory control (Cisler &

Koster, 2010). Even though there is a high rate for comorbidity of the anxiety disorders and

depression, above 75%, they have various underlying neural correlates. The high comorbidity

implies commonality in etiology (Peckham, McHugh & Otto, 2010). The dorsal anterior

cingulate cortex is involved in inhibitory cognitive control. It detects conflict between

CHAPTER TWO 4

competing neural representations in the perceptuo-motor system and gives a signal to the

dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex to help in adjusting the system to a regulated level.

Depression and clinical anxiety disorders are severe diseases that affect lives of people, both

mentally and physically (Association, 1998). Some symptoms appear in milder forms even

among individuals considered as psychologically healthy (Park et al., 2010). At the clinical

levels, anxiety and depression severely affect the inhibitory cognitive control (Eysneck &

Derakshan, 2007). The clinical symptoms show existence of some relationship withThere is

considerable decrease in activity within anterior cortical control structures which is

responsible for most cognitive functions including attention allocation, decision making,

impulse control etc. . For example, levels of clinical anxiety happen to inversely correlate to

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DIPFC) activity in a conflict task (Roma A., 2013). There

exists evidence of an inverse relationship between depression and resting-state activity

of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Robinson M. D., 2007). A highly depressed

individual has a hyperactive performance in the ACC, and at certain levels of anxiety and

depression, it goes into a resting state, bringing a halt to important cognitive functions like

attention allocation (Aaron T beck, Norman Epstein, & Robert a Steer, 1988). Moreover, as it

is evidenced that

Jjust like in clinical anxiety and depression, increased levels of subclinical anxiety and

depression symptoms occur together pointing to the likelihood of the same cause

(Pizzagalli et al., 2006). Taking this approach ends up in major theoretical challenges.

This is why most researchers treat the two as one, since they both point to the same

etiologies. in the interpretation of the finding that if anxiety and depression are related though

separate dysfunctions, then it means that their frequent co-occurrence results in considerable

muddle. Studies done by various authors (Sadock, 2009) and Anxiety And Depression

Association Of America (ADAA) show that anxiety and depression could have the same

competing neural representations in the perceptuo-motor system and gives a signal to the

dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex to help in adjusting the system to a regulated level.

Depression and clinical anxiety disorders are severe diseases that affect lives of people, both

mentally and physically (Association, 1998). Some symptoms appear in milder forms even

among individuals considered as psychologically healthy (Park et al., 2010). At the clinical

levels, anxiety and depression severely affect the inhibitory cognitive control (Eysneck &

Derakshan, 2007). The clinical symptoms show existence of some relationship withThere is

considerable decrease in activity within anterior cortical control structures which is

responsible for most cognitive functions including attention allocation, decision making,

impulse control etc. . For example, levels of clinical anxiety happen to inversely correlate to

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DIPFC) activity in a conflict task (Roma A., 2013). There

exists evidence of an inverse relationship between depression and resting-state activity

of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Robinson M. D., 2007). A highly depressed

individual has a hyperactive performance in the ACC, and at certain levels of anxiety and

depression, it goes into a resting state, bringing a halt to important cognitive functions like

attention allocation (Aaron T beck, Norman Epstein, & Robert a Steer, 1988). Moreover, as it

is evidenced that

Jjust like in clinical anxiety and depression, increased levels of subclinical anxiety and

depression symptoms occur together pointing to the likelihood of the same cause

(Pizzagalli et al., 2006). Taking this approach ends up in major theoretical challenges.

This is why most researchers treat the two as one, since they both point to the same

etiologies. in the interpretation of the finding that if anxiety and depression are related though

separate dysfunctions, then it means that their frequent co-occurrence results in considerable

muddle. Studies done by various authors (Sadock, 2009) and Anxiety And Depression

Association Of America (ADAA) show that anxiety and depression could have the same

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER TWO 5

or different causes or etiologies (Association, 1998), thus, it is acceptable to test the two

separately and compare results thereafter. Nonetheless, very few studies have focused

on determining the difference in anxiety level especially subclinical levels between young

and older adults. Coming up with a more conclusive distinction could help in developing

proper interventions aimed at minimizing the negative affective states of anxiety and

depression.We need to understand the difference between anxiety and depression terms, and

see how the levels of anxiety could lead to depression. We also need to clarify the big overlap

that exists between depression and anxiety as most studies normally treat them as one

disorder and a whole clinical illness. Coming up with a more conclusive distinction could

help in developing proper interventions aimed at minimizing the negative affective states of

anxiety and depression.

Anxiety and depression levels have been known to lower the cognitive performance of

people across all the age groups (Endler, Johnson, & Flett, 2001). These two emotions

have complex pathophysiology with many stimuli. Anatomically, emotions are

integrated by the limbic system. Well demonstrated by papiz circuit, cognition is a

higher function performed by the prefrontal cortex and involves formation of new

neurons and connections. Emotions and cognition share pathways depending on stimuli.

Anxiety and depression load the brain and cognition requires brain alertness. When the

two are active simultaneously, they interfere with C1 neurons and divert attention

making the brain less receptive and less effective in information integration (Shah A,

Jhawar, & Goel A, 2011). There is evidence of significant decline in cognitive abilities

among older adults considered to have anxiety disorders which result in cognitive

impairment (Price and Mohlman,2007). Apart from clinical experiments (Williams

JMG & MacLeod, 1998), subclinical anxiety levels have not been seriously researched

or different causes or etiologies (Association, 1998), thus, it is acceptable to test the two

separately and compare results thereafter. Nonetheless, very few studies have focused

on determining the difference in anxiety level especially subclinical levels between young

and older adults. Coming up with a more conclusive distinction could help in developing

proper interventions aimed at minimizing the negative affective states of anxiety and

depression.We need to understand the difference between anxiety and depression terms, and

see how the levels of anxiety could lead to depression. We also need to clarify the big overlap

that exists between depression and anxiety as most studies normally treat them as one

disorder and a whole clinical illness. Coming up with a more conclusive distinction could

help in developing proper interventions aimed at minimizing the negative affective states of

anxiety and depression.

Anxiety and depression levels have been known to lower the cognitive performance of

people across all the age groups (Endler, Johnson, & Flett, 2001). These two emotions

have complex pathophysiology with many stimuli. Anatomically, emotions are

integrated by the limbic system. Well demonstrated by papiz circuit, cognition is a

higher function performed by the prefrontal cortex and involves formation of new

neurons and connections. Emotions and cognition share pathways depending on stimuli.

Anxiety and depression load the brain and cognition requires brain alertness. When the

two are active simultaneously, they interfere with C1 neurons and divert attention

making the brain less receptive and less effective in information integration (Shah A,

Jhawar, & Goel A, 2011). There is evidence of significant decline in cognitive abilities

among older adults considered to have anxiety disorders which result in cognitive

impairment (Price and Mohlman,2007). Apart from clinical experiments (Williams

JMG & MacLeod, 1998), subclinical anxiety levels have not been seriously researched

CHAPTER TWO 6

on in relation to depression and cognitive impairment in a population-based sample

across all age groups. Non-clinical anxiety affects both subjective and objective

cognitive and memory processing ability of any individual, though no extensive research

has been done on effects of anxiety on attention and information processing speed.

Goldberg et al., (2003) compared the effect of anxiety and depression on cognitive

function of older and younger people and found that the cognitive ability of the

youngerolder group is lowered in relation to thought process, perception and general

problem solving, more than that of the olderyounger group. However, Unterrainer et al.,

(2018) differ with this observation based on the evidence from their study, that

subclinical low anxiety levels and cognitive function of people are not related regardless

of age. The associations they observed in clinical groups differed with ones in

population-based samples. Higher ratings of anxiety were associated with lower

planning performance independent of age. When they directly compared predictive

values of depression and anxiety on cognitive ability, significance was only attained by

anxiety while depression did not. The evidence from the two studies, Mattay et al.,

(2003) and Unterrainer et al., (2018) do not adequately explain the explain the difference

in effects of subclinical anxiety levels on cognitive function of individuals. Translational

threats of arbitrary shock paradigm and anxiety levels that cause them is examined in this

study, including the amount of emotional response caused by the different levels of anxiety.

This research explored this difference to help in better understanding of how different

levels of anxiety impair cognition and also help improve measures in place to treat

patients with cognitive problems caused by non-clinical anxiety and depression. Young

and old people have significant differences in how the anxiety levels affect their

cognitive abilities. Old people are less susceptible to different anxiety levels than young

on in relation to depression and cognitive impairment in a population-based sample

across all age groups. Non-clinical anxiety affects both subjective and objective

cognitive and memory processing ability of any individual, though no extensive research

has been done on effects of anxiety on attention and information processing speed.

Goldberg et al., (2003) compared the effect of anxiety and depression on cognitive

function of older and younger people and found that the cognitive ability of the

youngerolder group is lowered in relation to thought process, perception and general

problem solving, more than that of the olderyounger group. However, Unterrainer et al.,

(2018) differ with this observation based on the evidence from their study, that

subclinical low anxiety levels and cognitive function of people are not related regardless

of age. The associations they observed in clinical groups differed with ones in

population-based samples. Higher ratings of anxiety were associated with lower

planning performance independent of age. When they directly compared predictive

values of depression and anxiety on cognitive ability, significance was only attained by

anxiety while depression did not. The evidence from the two studies, Mattay et al.,

(2003) and Unterrainer et al., (2018) do not adequately explain the explain the difference

in effects of subclinical anxiety levels on cognitive function of individuals. Translational

threats of arbitrary shock paradigm and anxiety levels that cause them is examined in this

study, including the amount of emotional response caused by the different levels of anxiety.

This research explored this difference to help in better understanding of how different

levels of anxiety impair cognition and also help improve measures in place to treat

patients with cognitive problems caused by non-clinical anxiety and depression. Young

and old people have significant differences in how the anxiety levels affect their

cognitive abilities. Old people are less susceptible to different anxiety levels than young

CHAPTER TWO 7

people as will be seen in results section, which is in concurrence with previous studies

(Administration, 2013). This is mostly because old people are more settled and do not

worry about life and all its troubles. They are more interested in living in peace and

integrity. Subjective and objective cognitive functions are key elements in this study

since they determine how anxiety levels influence cognitive functions of both old and

young groups.

Although anxiety has been investigated in ageing, young vs old, it has only been on

clinical levels or as a part of depression. Similarly, anxiety studies on ageing in relation to

demographic factors has only been on a clinical scale. This study works on the

subclinical anxiety level.

Most of the studies on effect of anxiety and depression on cognition have been on the

relation to anxiety in general but there is a recognized investigation that has mainly

targeted the adults (DiMatteo, Lepper, & Croghan, 2000). A number of studies on

anxiety and cognition have targeted individuals who have mild cognitive impairment

(MCI) and dementia, others focusing on formal anxiety disorders (Tales, & Basoudan,

2016). Non-clinical anxiety can affect elements of information processing than the ones

that were earlier recognized (Tales & Basoudan, 2016).

For a very long time most of the studies relating anxiety and age have focused on

subclinical level in the older adults. Few studies have focused on subclinical anxiety among

the youthyoung and older adults. Other studies have focused on effects of depressive

symptoms on cognition in the elderly (Sinn, Milte, Street, & Buckley, 2012) and looked at

anxiety as a part or one with od depression symptoms. Though anxiety and depression has

been associated with negative effect on cognition function, the correlation to the

subclinical anxiety level in the youth and older adults has not been exploredsubclinical

people as will be seen in results section, which is in concurrence with previous studies

(Administration, 2013). This is mostly because old people are more settled and do not

worry about life and all its troubles. They are more interested in living in peace and

integrity. Subjective and objective cognitive functions are key elements in this study

since they determine how anxiety levels influence cognitive functions of both old and

young groups.

Although anxiety has been investigated in ageing, young vs old, it has only been on

clinical levels or as a part of depression. Similarly, anxiety studies on ageing in relation to

demographic factors has only been on a clinical scale. This study works on the

subclinical anxiety level.

Most of the studies on effect of anxiety and depression on cognition have been on the

relation to anxiety in general but there is a recognized investigation that has mainly

targeted the adults (DiMatteo, Lepper, & Croghan, 2000). A number of studies on

anxiety and cognition have targeted individuals who have mild cognitive impairment

(MCI) and dementia, others focusing on formal anxiety disorders (Tales, & Basoudan,

2016). Non-clinical anxiety can affect elements of information processing than the ones

that were earlier recognized (Tales & Basoudan, 2016).

For a very long time most of the studies relating anxiety and age have focused on

subclinical level in the older adults. Few studies have focused on subclinical anxiety among

the youthyoung and older adults. Other studies have focused on effects of depressive

symptoms on cognition in the elderly (Sinn, Milte, Street, & Buckley, 2012) and looked at

anxiety as a part or one with od depression symptoms. Though anxiety and depression has

been associated with negative effect on cognition function, the correlation to the

subclinical anxiety level in the youth and older adults has not been exploredsubclinical

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CHAPTER TWO 8

anxiety hasn’t been studied separately from depression (Balash et al., 2013). It is against

this background that the study examines the difference in subclinical anxiety level

between young and older adults and their links to depression, demographic parameters

and its effects on cognition. This study will also allow us to understand the differences

between young and old in terms of anxiety very well, in relation to many factors before

looking deeply on attention and information processing speed.

The aim of this research is to examine the non-clinical anxiety, and its effects on individuals

and on different degrees.

METHODS

This section briefly describes the methods used to conduct the investigation, including

participants, measuring instruments, and other details of how the research was

conducted.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the guidance and approval of the Research Ethics

Committee at the University Department of Psychology, which mandates informed

consent of all participants, along with their rights to withdraw from the study at any

time. The informed consent form was signed by all participants. All data collected in

this study was blinded to participant identity and stored under password protection on

the researcher’s computer. All the data is confidential and only accessible to responsible

authorities. All data collected was used for empirical research, and not for any medical

purpose.

anxiety hasn’t been studied separately from depression (Balash et al., 2013). It is against

this background that the study examines the difference in subclinical anxiety level

between young and older adults and their links to depression, demographic parameters

and its effects on cognition. This study will also allow us to understand the differences

between young and old in terms of anxiety very well, in relation to many factors before

looking deeply on attention and information processing speed.

The aim of this research is to examine the non-clinical anxiety, and its effects on individuals

and on different degrees.

METHODS

This section briefly describes the methods used to conduct the investigation, including

participants, measuring instruments, and other details of how the research was

conducted.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the guidance and approval of the Research Ethics

Committee at the University Department of Psychology, which mandates informed

consent of all participants, along with their rights to withdraw from the study at any

time. The informed consent form was signed by all participants. All data collected in

this study was blinded to participant identity and stored under password protection on

the researcher’s computer. All the data is confidential and only accessible to responsible

authorities. All data collected was used for empirical research, and not for any medical

purpose.

CHAPTER TWO 9

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited, older and younger adults. The young group

comprised of students (n=52; age 18-25 years, 21 males: 31 females) recruited from the

Psychology Department at the University. The older group of participants (n=52; age

50-80 years, 31 females: 21 males) were recruited from the community. The average

age of the young individuals was 19.92 (SD=1.57) whereas that of older adults was 66.47

(SD=4.52). In the younger group, those who participated received 6 credits; older adult

participants received transportation expense assistance only. The young adults were

recruited through the Psychology Subject Pool System. while the older adults were

identified and approached by via emails and telephone; advertisement in local

newspapers, posters and flyers made the local population aware of the study while the

older adults were identified and approached by the department and requested if they would

want to be part of this study. The selection used inclusion criteria that involved

individuals who were not suffering from any clinical anxiety disorder and illustrated

regular medical visits indicating good health and no history of neurological and

cognitive visual impairments; the participants who exhibited severe depression and

previous history of poor health were excluded. Other exclusions included poor self-

reported general health; past history of head injury or neurological, medical, or

psychological problems; reported cognitive impairment; vision not normal or corrected

to normal; and self-reported medications that impact cognitive functioning. Two males

were excluded from the younger group and one male excluded from the older group due

to severe depression scores in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The participants were

briefed about the objectives of the study and its importance to the field of psychology.

After completing the study, debriefing forms were given to them. All the participants

had normal general cognition score (26 or above) that was measured through Montreal

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited, older and younger adults. The young group

comprised of students (n=52; age 18-25 years, 21 males: 31 females) recruited from the

Psychology Department at the University. The older group of participants (n=52; age

50-80 years, 31 females: 21 males) were recruited from the community. The average

age of the young individuals was 19.92 (SD=1.57) whereas that of older adults was 66.47

(SD=4.52). In the younger group, those who participated received 6 credits; older adult

participants received transportation expense assistance only. The young adults were

recruited through the Psychology Subject Pool System. while the older adults were

identified and approached by via emails and telephone; advertisement in local

newspapers, posters and flyers made the local population aware of the study while the

older adults were identified and approached by the department and requested if they would

want to be part of this study. The selection used inclusion criteria that involved

individuals who were not suffering from any clinical anxiety disorder and illustrated

regular medical visits indicating good health and no history of neurological and

cognitive visual impairments; the participants who exhibited severe depression and

previous history of poor health were excluded. Other exclusions included poor self-

reported general health; past history of head injury or neurological, medical, or

psychological problems; reported cognitive impairment; vision not normal or corrected

to normal; and self-reported medications that impact cognitive functioning. Two males

were excluded from the younger group and one male excluded from the older group due

to severe depression scores in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The participants were

briefed about the objectives of the study and its importance to the field of psychology.

After completing the study, debriefing forms were given to them. All the participants

had normal general cognition score (26 or above) that was measured through Montreal

CHAPTER TWO 10

Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). This approach detects objective cognitive functioning

and mild cognitive impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention,

concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction,

calculation, and orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a

variety of verbal and pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a

diagram of a cube, and doing delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges

from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont and &

Nasreddine, 2017).

Data Collection

The demographic data collected included age, gender, years of education, handedness

and vision. Some of the instruments used included consent form, information sheet and

debriefing form, questionnaire as well as demographics form, all found in Appendix A.

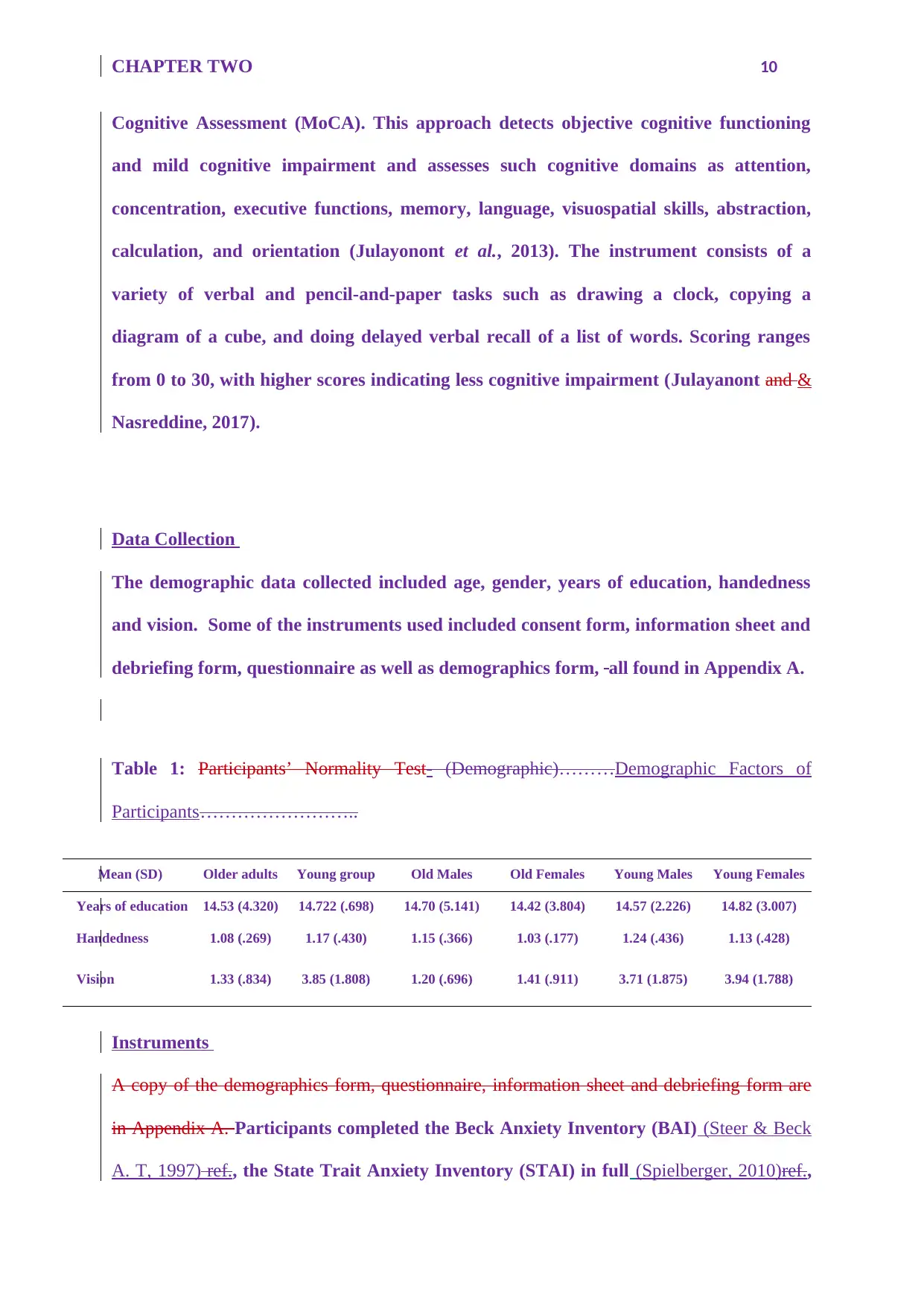

Table 1: Participants’ Normality Test- (Demographic)………Demographic Factors of

Participants……………………..

Mean (SD) Older adults Young group Old Males Old Females Young Males Young Females

Years of education 14.53 (4.320) 14.722 (.698) 14.70 (5.141) 14.42 (3.804) 14.57 (2.226) 14.82 (3.007)

Handedness 1.08 (.269) 1.17 (.430) 1.15 (.366) 1.03 (.177) 1.24 (.436) 1.13 (.428)

Vision 1.33 (.834) 3.85 (1.808) 1.20 (.696) 1.41 (.911) 3.71 (1.875) 3.94 (1.788)

Instruments

A copy of the demographics form, questionnaire, information sheet and debriefing form are

in Appendix A. Participants completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Steer & Beck

A. T, 1997) ref., the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in full (Spielberger, 2010)ref.,

Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). This approach detects objective cognitive functioning

and mild cognitive impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention,

concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction,

calculation, and orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a

variety of verbal and pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a

diagram of a cube, and doing delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges

from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont and &

Nasreddine, 2017).

Data Collection

The demographic data collected included age, gender, years of education, handedness

and vision. Some of the instruments used included consent form, information sheet and

debriefing form, questionnaire as well as demographics form, all found in Appendix A.

Table 1: Participants’ Normality Test- (Demographic)………Demographic Factors of

Participants……………………..

Mean (SD) Older adults Young group Old Males Old Females Young Males Young Females

Years of education 14.53 (4.320) 14.722 (.698) 14.70 (5.141) 14.42 (3.804) 14.57 (2.226) 14.82 (3.007)

Handedness 1.08 (.269) 1.17 (.430) 1.15 (.366) 1.03 (.177) 1.24 (.436) 1.13 (.428)

Vision 1.33 (.834) 3.85 (1.808) 1.20 (.696) 1.41 (.911) 3.71 (1.875) 3.94 (1.788)

Instruments

A copy of the demographics form, questionnaire, information sheet and debriefing form are

in Appendix A. Participants completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Steer & Beck

A. T, 1997) ref., the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in full (Spielberger, 2010)ref.,

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER TWO 11

including both the State and Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T), the Beck

Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Aarno T, & Robert A, 1996)ref., the Montreal

Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) version 7.1 (Ziad S Nasreddine & Phillips, 2005)ref., and

the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) (Slavin-Mulford &

Hilsenroth, 2012). Each of these instruments is described below:

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to determine participant anxiety levels

(Liang, Wang and Zhu, 2016). This test is a 21-item self-assessment using a four-point

Likert scale (0: “not at all” to 3: “severely”) that focuses on somatic symptoms of

anxiety as a way of distinguishing between anxiety and depression (Julian, 2011).

Scoring for the BAI is computed by adding the scores of the 21 items, and thus ranges

from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety levels. A score between from

0–21 indicates no to mild anxiety; a score between 22 and 35 indicates moderate

anxiety; and a score between 36 and 63 indicates potentially severe anxiety (Beck, 1988.

Reliability of the BAI has been shown with high internal consistency as measured by

Cronbach’s alpha (0.90 to 0.94).

State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI measures the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-

state anxiety in the present and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive

situations as threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two

separate 20-item scales, the STAI-S Anxiety scale that evaluates current state of anxiety,

and the STAI-T Anxiety scale that evaluates general, long-lasting feelings of anxiety

(Dennis, Coghlan and Vigod, 2013). Reliability of STAI is demonstrated in various

including both the State and Trait subsections (STAI-S and STAI-T), the Beck

Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Aarno T, & Robert A, 1996)ref., the Montreal

Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) version 7.1 (Ziad S Nasreddine & Phillips, 2005)ref., and

the Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) (Slavin-Mulford &

Hilsenroth, 2012). Each of these instruments is described below:

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to determine participant anxiety levels

(Liang, Wang and Zhu, 2016). This test is a 21-item self-assessment using a four-point

Likert scale (0: “not at all” to 3: “severely”) that focuses on somatic symptoms of

anxiety as a way of distinguishing between anxiety and depression (Julian, 2011).

Scoring for the BAI is computed by adding the scores of the 21 items, and thus ranges

from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety levels. A score between from

0–21 indicates no to mild anxiety; a score between 22 and 35 indicates moderate

anxiety; and a score between 36 and 63 indicates potentially severe anxiety (Beck, 1988.

Reliability of the BAI has been shown with high internal consistency as measured by

Cronbach’s alpha (0.90 to 0.94).

State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI measures the intensity of feelings of anxiety, differentiating between current-

state anxiety in the present and trait anxiety that is a general tendency to perceive

situations as threatening or anxiety-producing (McDowell, 2006). The full STAI has two

separate 20-item scales, the STAI-S Anxiety scale that evaluates current state of anxiety,

and the STAI-T Anxiety scale that evaluates general, long-lasting feelings of anxiety

(Dennis, Coghlan and Vigod, 2013). Reliability of STAI is demonstrated in various

CHAPTER TWO 12

publications (McDowell, 2006). The STAI and the BAI are sometimes suggested to

measure different factors of anxiety (McDowell, 2006). In studies of young adults, the

validity comparison between the BAI and the sister measure BDI, the STAI correlated

more closely with BDI than with BAI, implying that the STAI is actually a closer

measure of depression than anxiety (McDowell, 2006). This measure identifies the

current state of trait anxiety. State anxiety stays for a designated time and often is

resolved (Allan et al., 2014). In comparison, trait anxiety lingers for a long time. The

measure can effectively track trait or state anxiety through differentiation. Therefore, if

any individual develops trait anxiety, it could be easily detected using this parameter.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI is a 21-element self-reporting scale using a four-choice Likert scale (ranked

from 0 to 3). The possible scores range from 0 to 63, higher scores indicating greater or

more severe depression (de Oliveira and et.al., 2014). The questions in the BDI focus on

cognitive distortions common in those with depressive symptoms, such as “I blame

myself for everything bad that happens” (Farinde, 2013). It is designed for people who

are at least 13 years old, with scores greater than 21 indicating clinical depression, and

scores above 30 indicating severe depression. The BDI is designed to be simple to use

and quick to administer, taking less than 10 minutes (Farinde, 2013). The BDI has been

demonstrated to be valid and reliable in adolescent and elderly populations

(adolescents: Kauth & Zettle, 1990; elderly: Penk & Robinowitz, 1987; Scogin et al.,

1988; Wetherall & Gatz, 2005). Internal consistency of the BDI has been demonstrated

alphas approximating 0.91, and reliability in test-retest results over a one-week period

of 0.93.

publications (McDowell, 2006). The STAI and the BAI are sometimes suggested to

measure different factors of anxiety (McDowell, 2006). In studies of young adults, the

validity comparison between the BAI and the sister measure BDI, the STAI correlated

more closely with BDI than with BAI, implying that the STAI is actually a closer

measure of depression than anxiety (McDowell, 2006). This measure identifies the

current state of trait anxiety. State anxiety stays for a designated time and often is

resolved (Allan et al., 2014). In comparison, trait anxiety lingers for a long time. The

measure can effectively track trait or state anxiety through differentiation. Therefore, if

any individual develops trait anxiety, it could be easily detected using this parameter.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI is a 21-element self-reporting scale using a four-choice Likert scale (ranked

from 0 to 3). The possible scores range from 0 to 63, higher scores indicating greater or

more severe depression (de Oliveira and et.al., 2014). The questions in the BDI focus on

cognitive distortions common in those with depressive symptoms, such as “I blame

myself for everything bad that happens” (Farinde, 2013). It is designed for people who

are at least 13 years old, with scores greater than 21 indicating clinical depression, and

scores above 30 indicating severe depression. The BDI is designed to be simple to use

and quick to administer, taking less than 10 minutes (Farinde, 2013). The BDI has been

demonstrated to be valid and reliable in adolescent and elderly populations

(adolescents: Kauth & Zettle, 1990; elderly: Penk & Robinowitz, 1987; Scogin et al.,

1988; Wetherall & Gatz, 2005). Internal consistency of the BDI has been demonstrated

alphas approximating 0.91, and reliability in test-retest results over a one-week period

of 0.93.

CHAPTER TWO 13

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

The MoCA is designed to detect objective cognitive functioning and mild cognitive

impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention, concentration, executive

functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction, calculation, and

orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a variety of verbal and

pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a diagram of a cube, and doing

delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores

indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont and Nasreddine, 2017). The MoCA is

commonly used as a screening tool to detect cognitive impairment from Alzheimer’s

disease. This assessment has been used in order to understand the objective measure in

case of cognitive function (Smith, Gildeh, & Holmes, 2007). It was necessary to examine

the cognitive abilities of the participants and relate the findings to the level of anxiety

that they faced at any particular point to assess the effect of their anxiety, as this was

the focal point of the research.

Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ)

PRMQ is a self-reported instrument that measures prospective and retrospective

memory slips in ordinary living activities (Crawford, Crawford , G, EA, & S, 2003). The

instrument includes 16 items, each with five Likert-scale responses ranging from “very

often” (scored as a 5) to “never” (scored as a 1) in response to questions such as “Do you

forget something that you were told a few minutes before?” Half of the questions refer

to retrospective memory errors and half to prospective memory errors. Scores thus

range from 16 to 80. The reliability of the PRMQ has been estimated at 0.89 overall and

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

The MoCA is designed to detect objective cognitive functioning and mild cognitive

impairment and assesses such cognitive domains as attention, concentration, executive

functions, memory, language, visuospatial skills, abstraction, calculation, and

orientation (Julayonont et al., 2013). The instrument consists of a variety of verbal and

pencil-and-paper tasks such as drawing a clock, copying a diagram of a cube, and doing

delayed verbal recall of a list of words. Scoring ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores

indicating less cognitive impairment (Julayanont and Nasreddine, 2017). The MoCA is

commonly used as a screening tool to detect cognitive impairment from Alzheimer’s

disease. This assessment has been used in order to understand the objective measure in

case of cognitive function (Smith, Gildeh, & Holmes, 2007). It was necessary to examine

the cognitive abilities of the participants and relate the findings to the level of anxiety

that they faced at any particular point to assess the effect of their anxiety, as this was

the focal point of the research.

Prospective-Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ)

PRMQ is a self-reported instrument that measures prospective and retrospective

memory slips in ordinary living activities (Crawford, Crawford , G, EA, & S, 2003). The

instrument includes 16 items, each with five Likert-scale responses ranging from “very

often” (scored as a 5) to “never” (scored as a 1) in response to questions such as “Do you

forget something that you were told a few minutes before?” Half of the questions refer

to retrospective memory errors and half to prospective memory errors. Scores thus

range from 16 to 80. The reliability of the PRMQ has been estimated at 0.89 overall and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CHAPTER TWO 14

0.84 for prospective scale and 0.80 for the retrospective scale (Crawford et al., 2003). It

does not show any significant statistical variance for gender or age hence suitable for

both sexes (Crawford et al., 2003). For non-clinical populations, PRMQ has shown

mean total scores of 38.88 (SD=9.15), mean prospective scores on 8 items of 20.18

(SD=4.91) and mean retrospective scores on 8 items of 18.69 (SD=4.98) (Crawford et al.,

2003).

Prospective memory is the ability of an individual to remember planned actions. While

retrospective memory is memory regarding the past. Both prospective and retrospective

approaches are general and approximated measurement of memory as they don’t

involve any numerical data which would have been more accurate, and good or poor

memory is based on the judgement of the interested party performing memory tests on

subjects. The researcher can analyze whether the individual has the ability to remember

planned action or events. In case any individual shows lower memory, it can be

evaluated that they have some level of subclinical anxiety (Kliegel & Theodor, 2017), the

aim being to determine whether there’s any relationship between memory(subjective

memory) and anxiety in young and older adults while considering other factors like

demographics etc.

RESULTS

Normality Tests

0.84 for prospective scale and 0.80 for the retrospective scale (Crawford et al., 2003). It

does not show any significant statistical variance for gender or age hence suitable for

both sexes (Crawford et al., 2003). For non-clinical populations, PRMQ has shown

mean total scores of 38.88 (SD=9.15), mean prospective scores on 8 items of 20.18

(SD=4.91) and mean retrospective scores on 8 items of 18.69 (SD=4.98) (Crawford et al.,

2003).

Prospective memory is the ability of an individual to remember planned actions. While

retrospective memory is memory regarding the past. Both prospective and retrospective

approaches are general and approximated measurement of memory as they don’t

involve any numerical data which would have been more accurate, and good or poor

memory is based on the judgement of the interested party performing memory tests on

subjects. The researcher can analyze whether the individual has the ability to remember

planned action or events. In case any individual shows lower memory, it can be

evaluated that they have some level of subclinical anxiety (Kliegel & Theodor, 2017), the

aim being to determine whether there’s any relationship between memory(subjective

memory) and anxiety in young and older adults while considering other factors like

demographics etc.

RESULTS

Normality Tests

CHAPTER TWO 15

The data collected was analyzed using non-parametric techniques. Since the variables

were not evenly distributed, non-parametric methods were the most appropriate tests

for the data (Altman & Bland, 2009). Key parameters would be estimated from the sample.

The table above represents results from normality test for all the variables in the dataset based

on age group. Since the number of observations in the study is below 2000, Shapiro-Wilk

test was used to show normality of various variables based on age and gender. Both

groups lack a normal distribution in BAI, p<0.05. The observations in the young group

lack a normal distribution in state anxiety, p<0.05, whereas the observations for the

older adults are normally distributed in state anxiety, p>0.05. In trait anxiety, the young

group has a normal distribution, p>0.05, while the older adults lack a normal

distribution. The observations for both young and older adults lack a normal

distribution in BDI, p<0.05; this is similar for MoCA. Lastly, the observations for both

groups depict a normal distribution in PRMQ, p>0.05. As some of the data were normally

distributed and some of them not, SPSS non-parametric analysis was also conducted.

The second table shows normality results based on gender. The BAI observations for old

males, old females and young males lack normal distribution (p<0.05) whereas the data for

young females is normally distributed, p>0.05. The state anxiety observations for old males,

young males and young females have a normal distribution (p>0.05) whereas the data for old

females lack a normal distribution, p<0.05. The BDI observations for old males and old

females have a normal distribution (p>0.05) whereas that for young males and young females

are not normally distributed, p<0.05. Observations on MoCA lack normal distribution for

both old males and females (p<0.05) while that for young males and females have a normal

distribution, p>0.05. All the groups have a normal distribution from the PRMQ observations,

p>0.05.

The data collected was analyzed using non-parametric techniques. Since the variables

were not evenly distributed, non-parametric methods were the most appropriate tests

for the data (Altman & Bland, 2009). Key parameters would be estimated from the sample.

The table above represents results from normality test for all the variables in the dataset based

on age group. Since the number of observations in the study is below 2000, Shapiro-Wilk

test was used to show normality of various variables based on age and gender. Both

groups lack a normal distribution in BAI, p<0.05. The observations in the young group

lack a normal distribution in state anxiety, p<0.05, whereas the observations for the

older adults are normally distributed in state anxiety, p>0.05. In trait anxiety, the young

group has a normal distribution, p>0.05, while the older adults lack a normal

distribution. The observations for both young and older adults lack a normal

distribution in BDI, p<0.05; this is similar for MoCA. Lastly, the observations for both

groups depict a normal distribution in PRMQ, p>0.05. As some of the data were normally

distributed and some of them not, SPSS non-parametric analysis was also conducted.

The second table shows normality results based on gender. The BAI observations for old

males, old females and young males lack normal distribution (p<0.05) whereas the data for

young females is normally distributed, p>0.05. The state anxiety observations for old males,

young males and young females have a normal distribution (p>0.05) whereas the data for old

females lack a normal distribution, p<0.05. The BDI observations for old males and old

females have a normal distribution (p>0.05) whereas that for young males and young females

are not normally distributed, p<0.05. Observations on MoCA lack normal distribution for

both old males and females (p<0.05) while that for young males and females have a normal

distribution, p>0.05. All the groups have a normal distribution from the PRMQ observations,

p>0.05.

CHAPTER TWO 16

Age Comparison: Anxiety levels

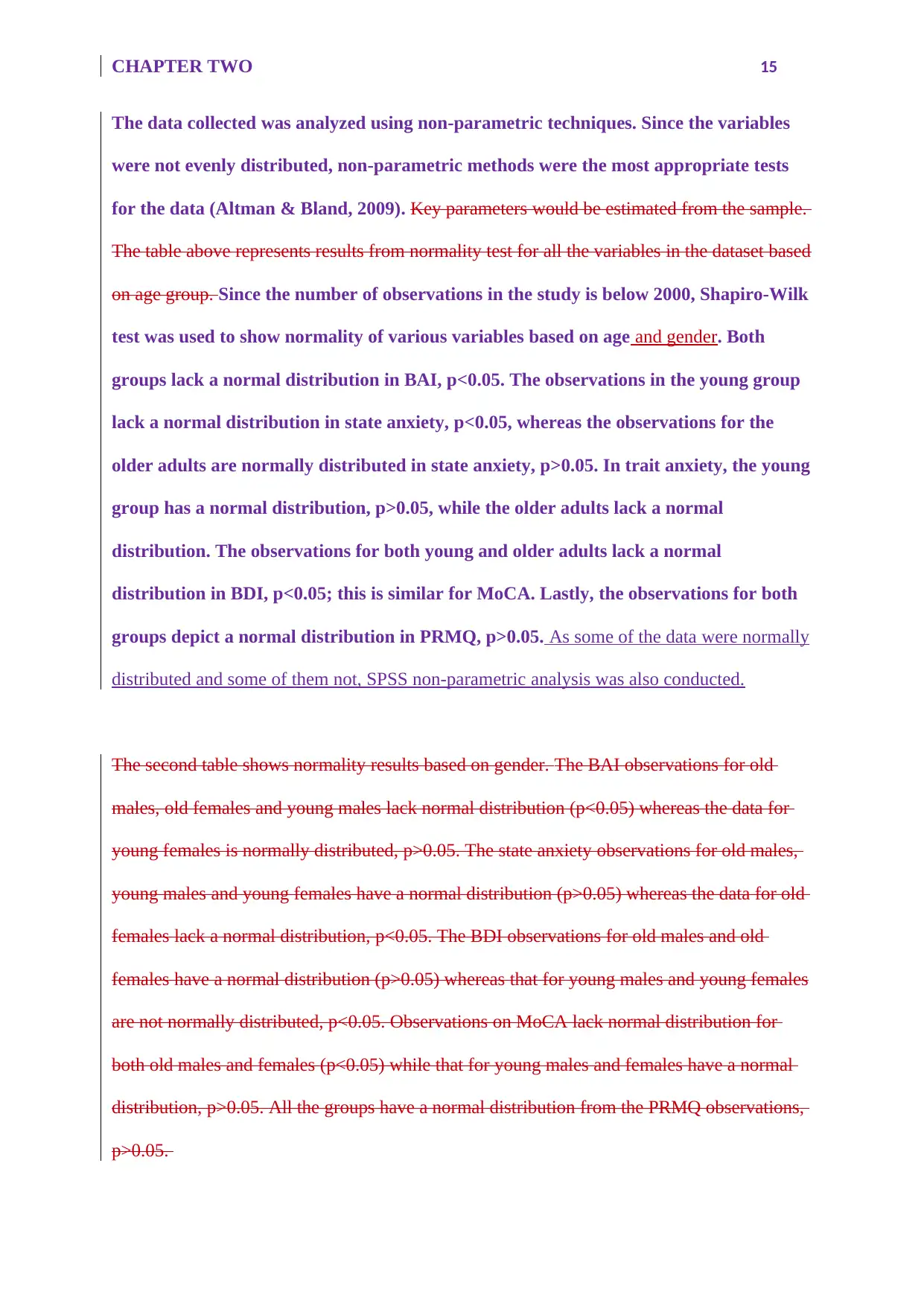

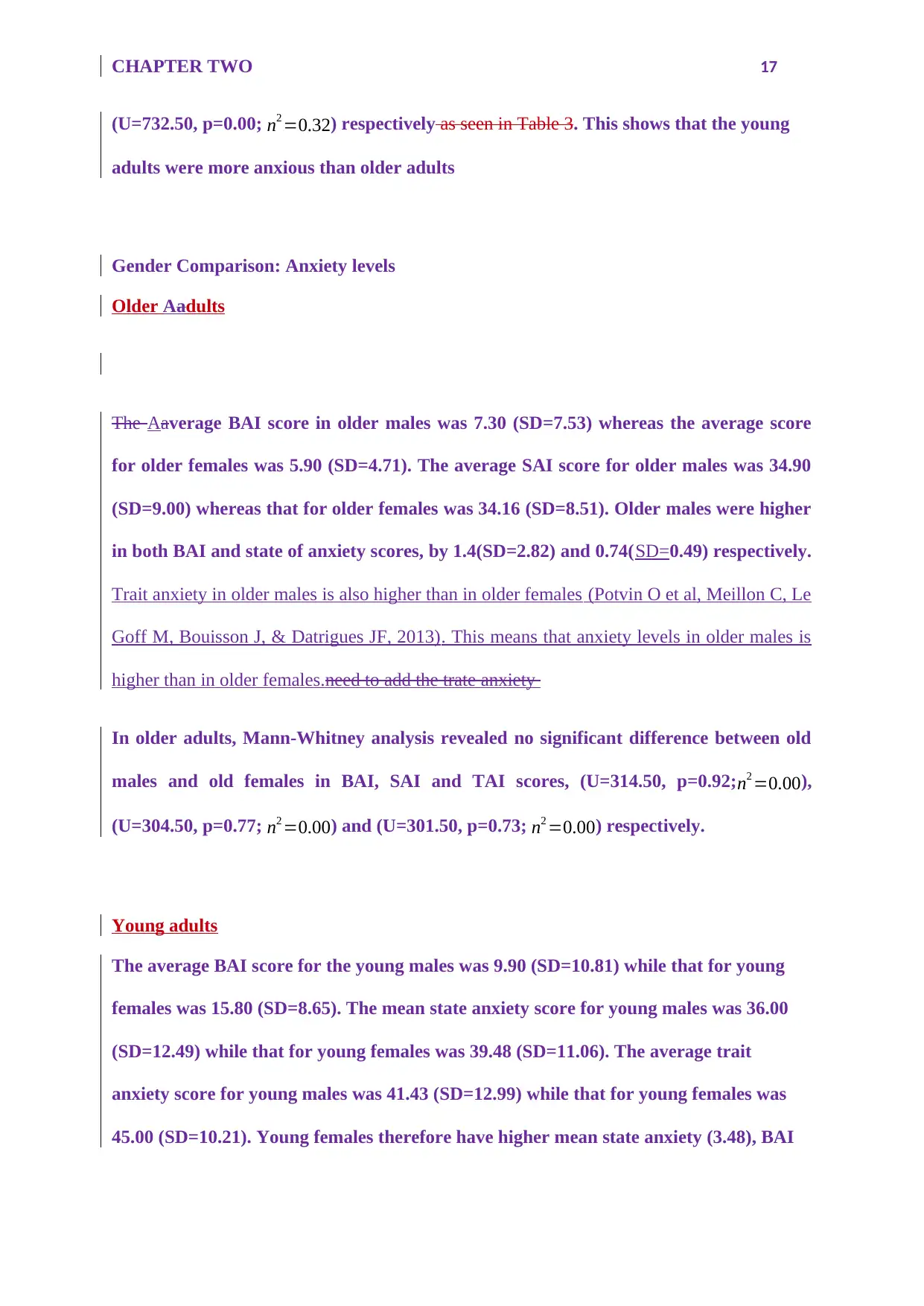

The average BAI score for older adults was 6.44 (SD=5.93) whereas the average BAI

score for the young group was 13.42 (SD=9.92). The young adults’ score is higher by

6.98 (SD=3.99). The average state anxiety score for the older adults was 29.62 (10.97)

while that for the young group was 38.08 (11.67), making young group 8.46 (0.7) more

anxious. The average trait anxiety score for the older group was 34.44 (8.62) whereas

that for the young group was 43.56 (SD=11.42). This means that anxiety levels of anxiety

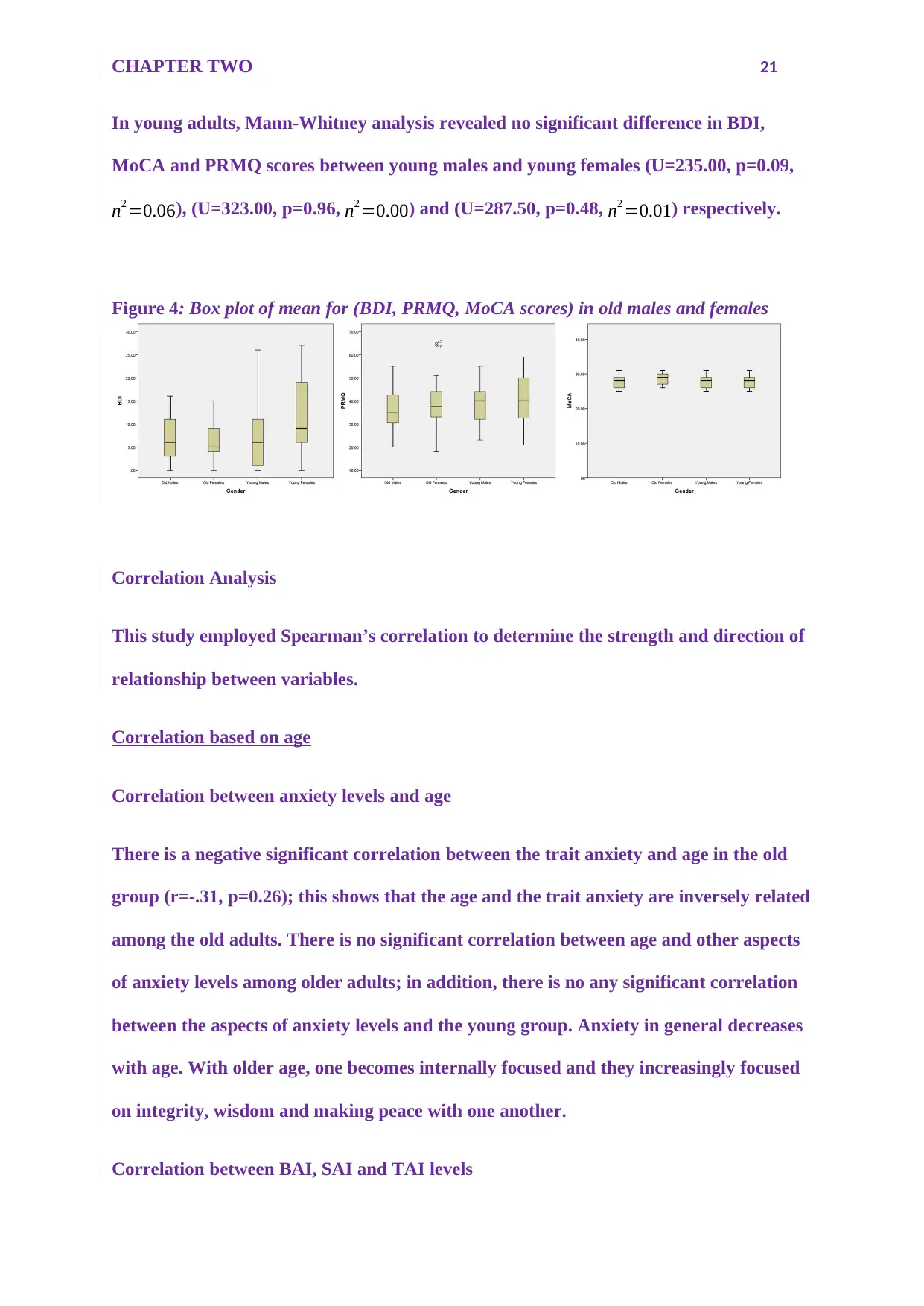

in the young people is more than that of older people. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: Box plot of mean non-clinical anxiety levels (BAI, SAI and TAI Scores) based

on age group

Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the difference in anxiety scores between

the young and the older groups. The null hypothesis that was tested states that there is

no significant difference in the anxiety scores between the young and the older adults.

There was a significant difference in the BAI, SAI and TAI scores between the young

and older adults (U=742.00, p=0.00; n2 =0.31), (U=708.50, p=0.00; n2 =0.34) and

Age Comparison: Anxiety levels

The average BAI score for older adults was 6.44 (SD=5.93) whereas the average BAI

score for the young group was 13.42 (SD=9.92). The young adults’ score is higher by

6.98 (SD=3.99). The average state anxiety score for the older adults was 29.62 (10.97)

while that for the young group was 38.08 (11.67), making young group 8.46 (0.7) more

anxious. The average trait anxiety score for the older group was 34.44 (8.62) whereas

that for the young group was 43.56 (SD=11.42). This means that anxiety levels of anxiety

in the young people is more than that of older people. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: Box plot of mean non-clinical anxiety levels (BAI, SAI and TAI Scores) based

on age group

Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the difference in anxiety scores between

the young and the older groups. The null hypothesis that was tested states that there is

no significant difference in the anxiety scores between the young and the older adults.

There was a significant difference in the BAI, SAI and TAI scores between the young

and older adults (U=742.00, p=0.00; n2 =0.31), (U=708.50, p=0.00; n2 =0.34) and

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER TWO 17

(U=732.50, p=0.00; n2 =0.32) respectively as seen in Table 3. This shows that the young

adults were more anxious than older adults

Gender Comparison: Anxiety levels

Older Aadults

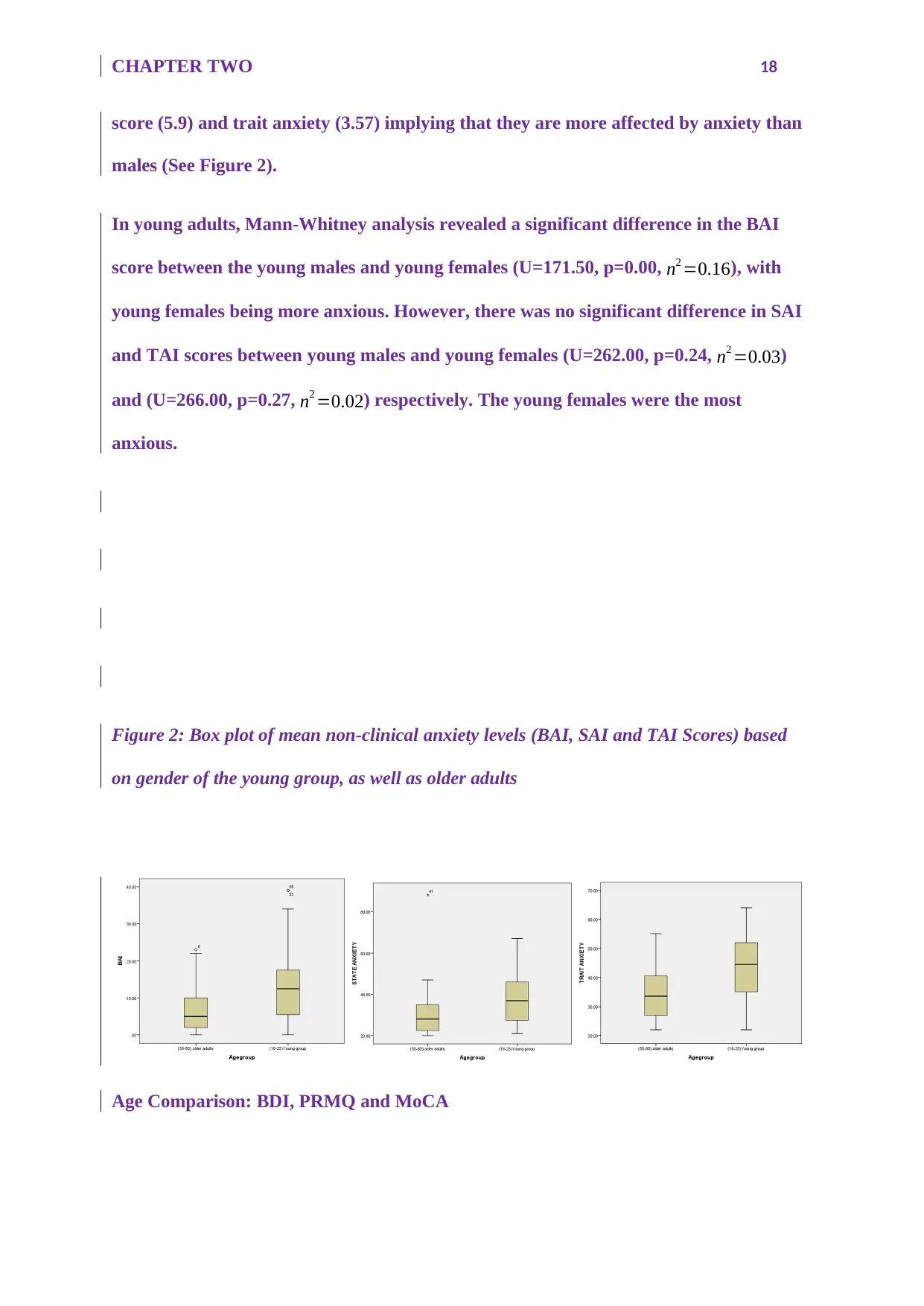

The Aaverage BAI score in older males was 7.30 (SD=7.53) whereas the average score

for older females was 5.90 (SD=4.71). The average SAI score for older males was 34.90

(SD=9.00) whereas that for older females was 34.16 (SD=8.51). Older males were higher

in both BAI and state of anxiety scores, by 1.4(SD=2.82) and 0.74(SD=0.49) respectively.

Trait anxiety in older males is also higher than in older females (Potvin O et al, Meillon C, Le

Goff M, Bouisson J, & Datrigues JF, 2013). This means that anxiety levels in older males is

higher than in older females.need to add the trate anxiety

In older adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference between old

males and old females in BAI, SAI and TAI scores, (U=314.50, p=0.92; n2 =0.00),

(U=304.50, p=0.77; n2 =0.00) and (U=301.50, p=0.73; n2 =0.00) respectively.

Young adults

The average BAI score for the young males was 9.90 (SD=10.81) while that for young

females was 15.80 (SD=8.65). The mean state anxiety score for young males was 36.00

(SD=12.49) while that for young females was 39.48 (SD=11.06). The average trait

anxiety score for young males was 41.43 (SD=12.99) while that for young females was

45.00 (SD=10.21). Young females therefore have higher mean state anxiety (3.48), BAI

(U=732.50, p=0.00; n2 =0.32) respectively as seen in Table 3. This shows that the young

adults were more anxious than older adults

Gender Comparison: Anxiety levels

Older Aadults

The Aaverage BAI score in older males was 7.30 (SD=7.53) whereas the average score

for older females was 5.90 (SD=4.71). The average SAI score for older males was 34.90

(SD=9.00) whereas that for older females was 34.16 (SD=8.51). Older males were higher

in both BAI and state of anxiety scores, by 1.4(SD=2.82) and 0.74(SD=0.49) respectively.

Trait anxiety in older males is also higher than in older females (Potvin O et al, Meillon C, Le

Goff M, Bouisson J, & Datrigues JF, 2013). This means that anxiety levels in older males is

higher than in older females.need to add the trate anxiety

In older adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference between old

males and old females in BAI, SAI and TAI scores, (U=314.50, p=0.92; n2 =0.00),

(U=304.50, p=0.77; n2 =0.00) and (U=301.50, p=0.73; n2 =0.00) respectively.

Young adults

The average BAI score for the young males was 9.90 (SD=10.81) while that for young

females was 15.80 (SD=8.65). The mean state anxiety score for young males was 36.00

(SD=12.49) while that for young females was 39.48 (SD=11.06). The average trait

anxiety score for young males was 41.43 (SD=12.99) while that for young females was

45.00 (SD=10.21). Young females therefore have higher mean state anxiety (3.48), BAI

CHAPTER TWO 18

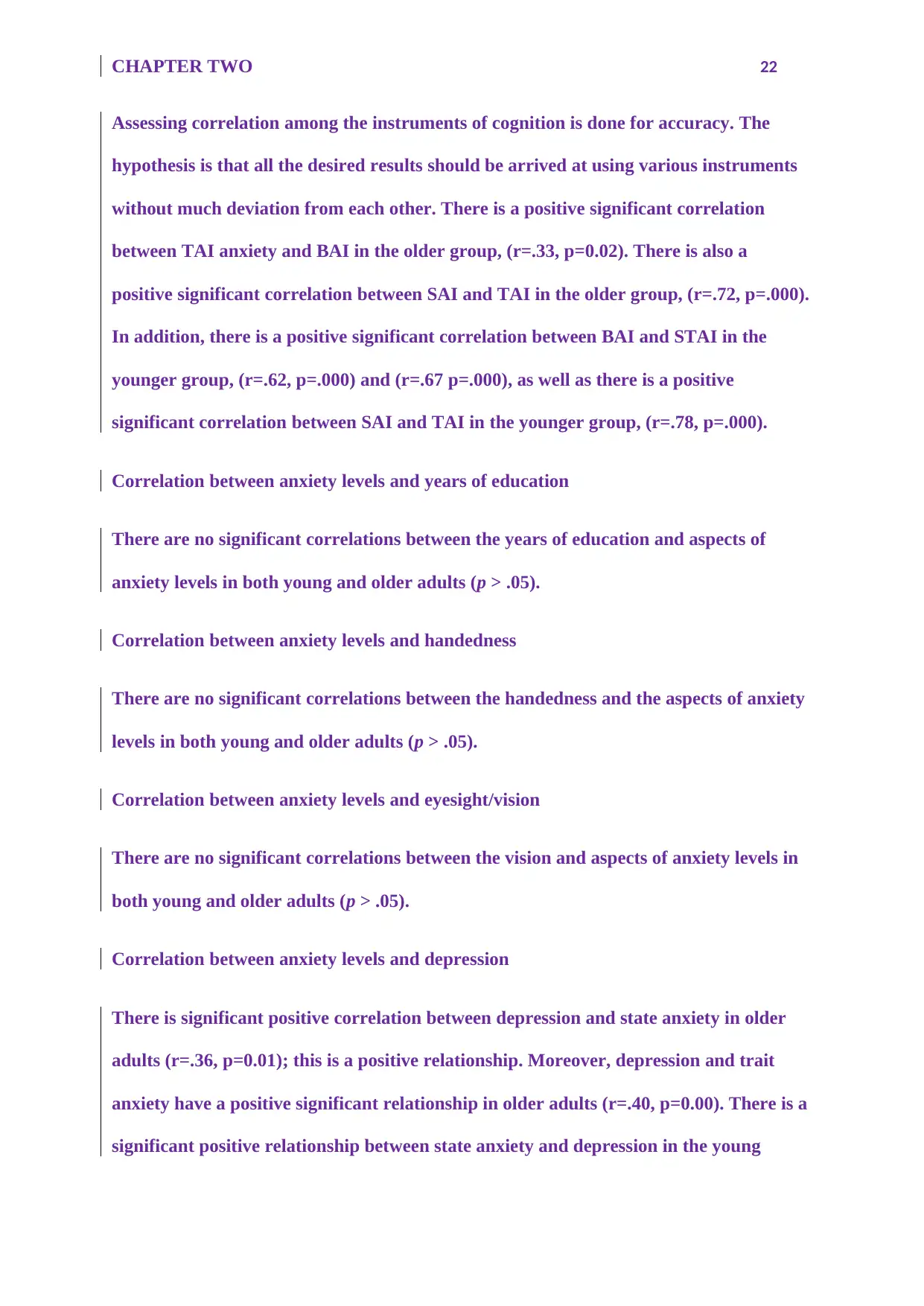

score (5.9) and trait anxiety (3.57) implying that they are more affected by anxiety than

males (See Figure 2).

In young adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed a significant difference in the BAI

score between the young males and young females (U=171.50, p=0.00, n2 =0.16), with

young females being more anxious. However, there was no significant difference in SAI

and TAI scores between young males and young females (U=262.00, p=0.24, n2 =0.03)

and (U=266.00, p=0.27, n2 =0.02) respectively. The young females were the most

anxious.

Figure 2: Box plot of mean non-clinical anxiety levels (BAI, SAI and TAI Scores) based

on gender of the young group, as well as older adults

Age Comparison: BDI, PRMQ and MoCA

score (5.9) and trait anxiety (3.57) implying that they are more affected by anxiety than

males (See Figure 2).

In young adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed a significant difference in the BAI

score between the young males and young females (U=171.50, p=0.00, n2 =0.16), with

young females being more anxious. However, there was no significant difference in SAI

and TAI scores between young males and young females (U=262.00, p=0.24, n2 =0.03)

and (U=266.00, p=0.27, n2 =0.02) respectively. The young females were the most

anxious.

Figure 2: Box plot of mean non-clinical anxiety levels (BAI, SAI and TAI Scores) based

on gender of the young group, as well as older adults

Age Comparison: BDI, PRMQ and MoCA

CHAPTER TWO 19

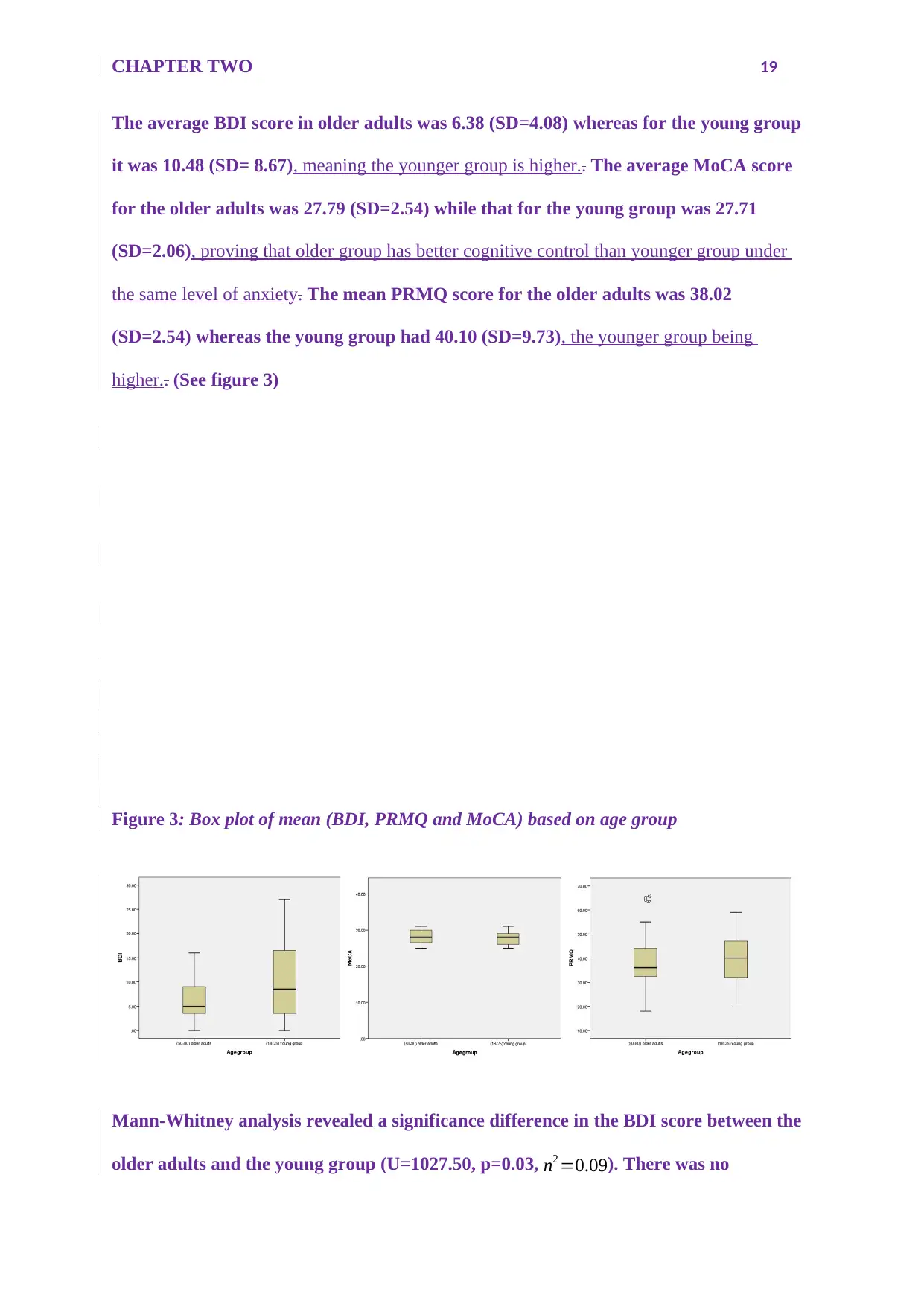

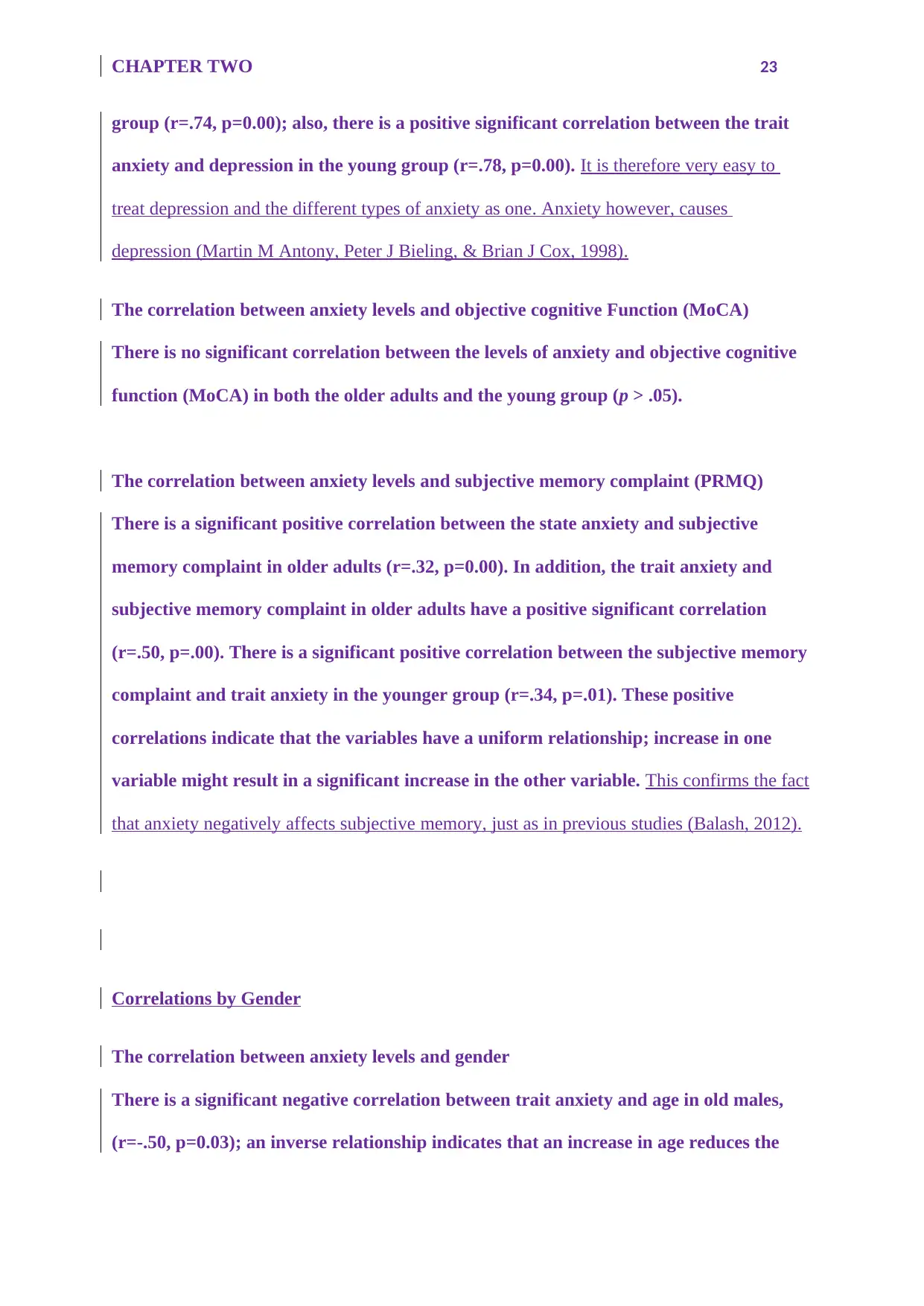

The average BDI score in older adults was 6.38 (SD=4.08) whereas for the young group

it was 10.48 (SD= 8.67), meaning the younger group is higher.. The average MoCA score

for the older adults was 27.79 (SD=2.54) while that for the young group was 27.71

(SD=2.06), proving that older group has better cognitive control than younger group under

the same level of anxiety. The mean PRMQ score for the older adults was 38.02

(SD=2.54) whereas the young group had 40.10 (SD=9.73), the younger group being

higher.. (See figure 3)

Figure 3: Box plot of mean (BDI, PRMQ and MoCA) based on age group

Mann-Whitney analysis revealed a significance difference in the BDI score between the

older adults and the young group (U=1027.50, p=0.03, n2 =0.09). There was no

The average BDI score in older adults was 6.38 (SD=4.08) whereas for the young group

it was 10.48 (SD= 8.67), meaning the younger group is higher.. The average MoCA score

for the older adults was 27.79 (SD=2.54) while that for the young group was 27.71

(SD=2.06), proving that older group has better cognitive control than younger group under

the same level of anxiety. The mean PRMQ score for the older adults was 38.02

(SD=2.54) whereas the young group had 40.10 (SD=9.73), the younger group being

higher.. (See figure 3)

Figure 3: Box plot of mean (BDI, PRMQ and MoCA) based on age group

Mann-Whitney analysis revealed a significance difference in the BDI score between the

older adults and the young group (U=1027.50, p=0.03, n2 =0.09). There was no

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CHAPTER TWO 20

significant difference in MoCA and PRMQ scores between the young and older groups

(U=1265.00, p=0.57, n2 =0.01) and (U=1150.50, p=0.19, n2 =0.03) respectively.

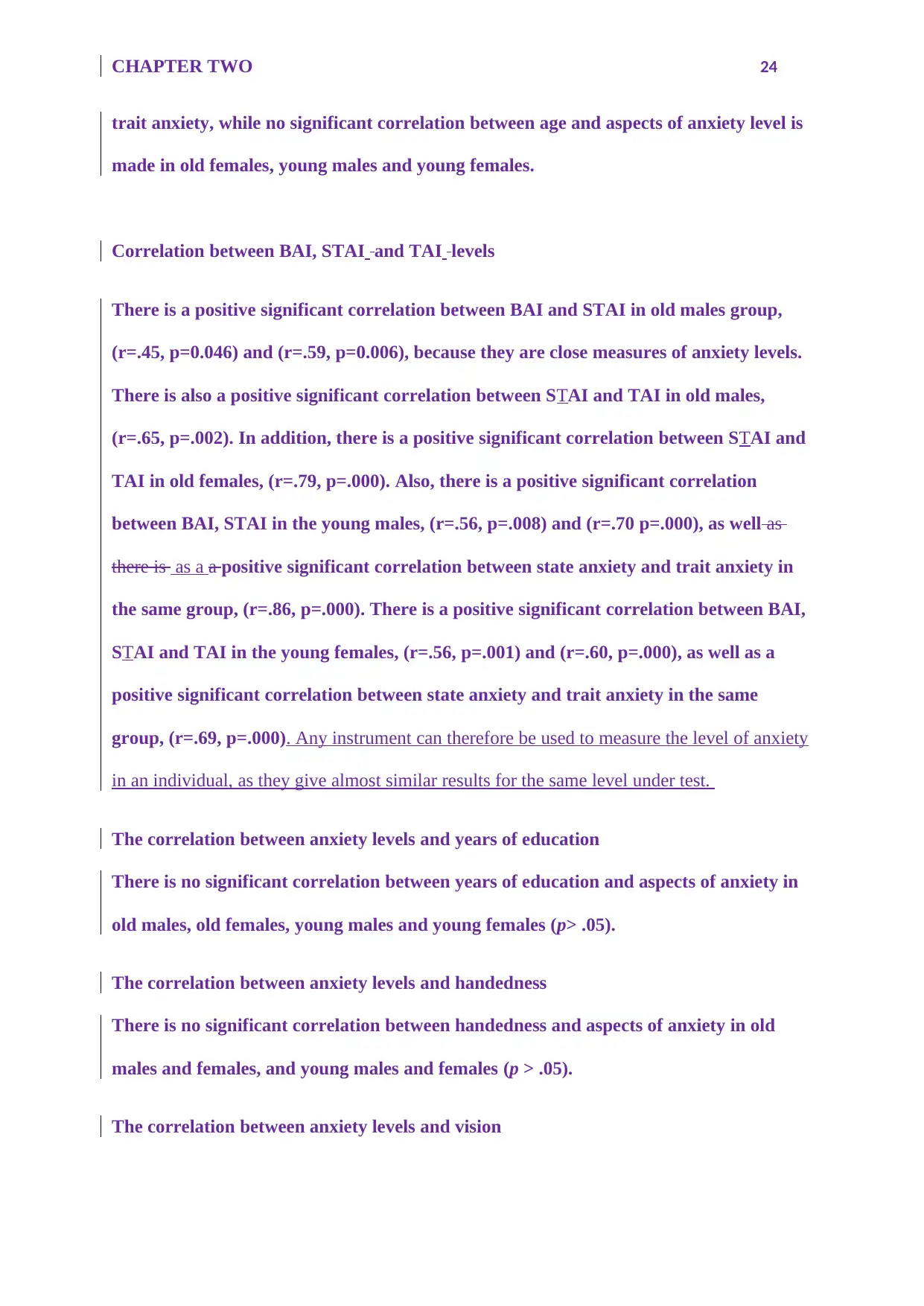

Gender Comparison: BDI, PRMQ and MoCA

Older adults

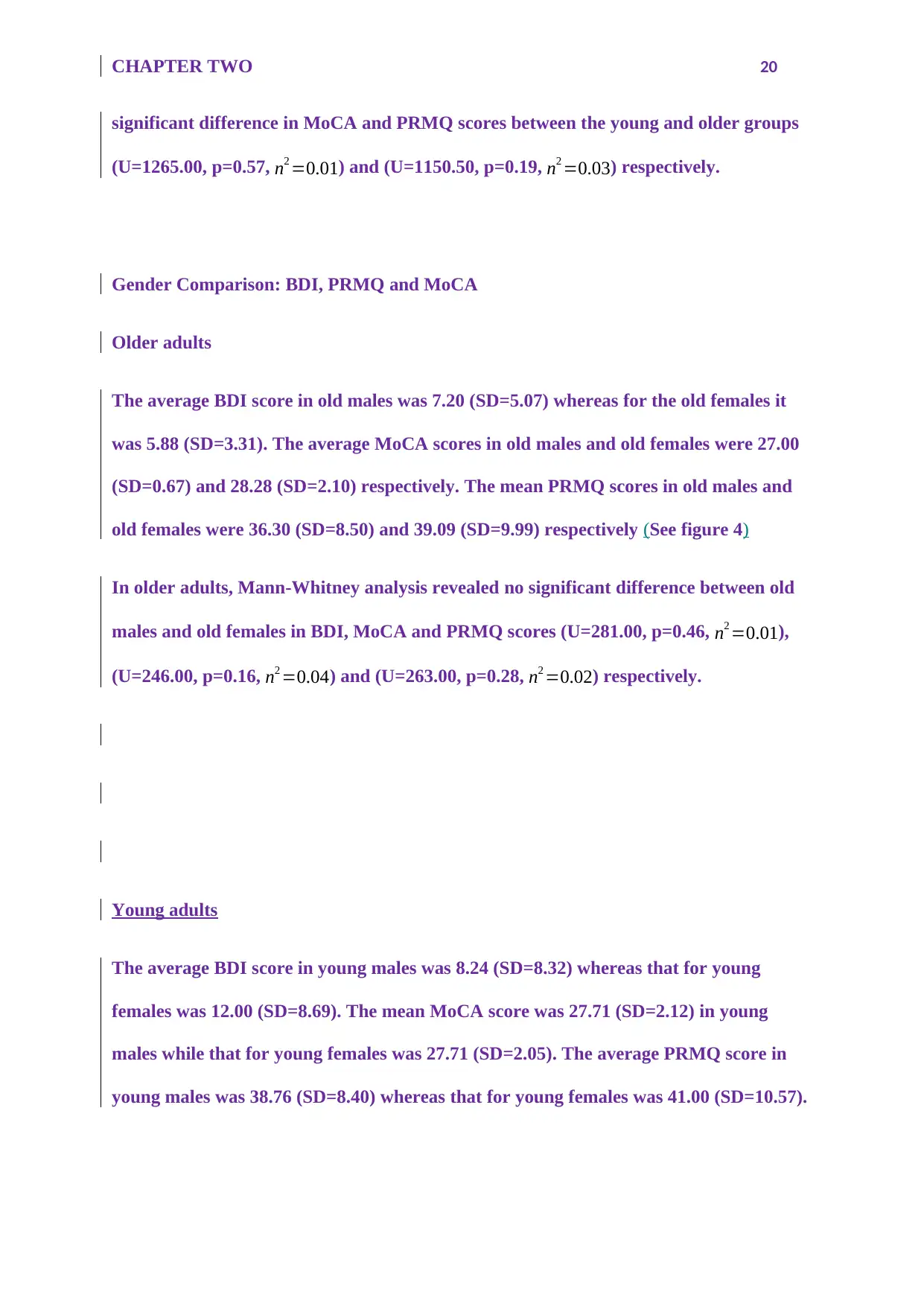

The average BDI score in old males was 7.20 (SD=5.07) whereas for the old females it

was 5.88 (SD=3.31). The average MoCA scores in old males and old females were 27.00

(SD=0.67) and 28.28 (SD=2.10) respectively. The mean PRMQ scores in old males and

old females were 36.30 (SD=8.50) and 39.09 (SD=9.99) respectively (See figure 4)

In older adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference between old

males and old females in BDI, MoCA and PRMQ scores (U=281.00, p=0.46, n2 =0.01),

(U=246.00, p=0.16, n2 =0.04) and (U=263.00, p=0.28, n2 =0.02) respectively.

Young adults

The average BDI score in young males was 8.24 (SD=8.32) whereas that for young

females was 12.00 (SD=8.69). The mean MoCA score was 27.71 (SD=2.12) in young

males while that for young females was 27.71 (SD=2.05). The average PRMQ score in

young males was 38.76 (SD=8.40) whereas that for young females was 41.00 (SD=10.57).

significant difference in MoCA and PRMQ scores between the young and older groups

(U=1265.00, p=0.57, n2 =0.01) and (U=1150.50, p=0.19, n2 =0.03) respectively.

Gender Comparison: BDI, PRMQ and MoCA

Older adults

The average BDI score in old males was 7.20 (SD=5.07) whereas for the old females it

was 5.88 (SD=3.31). The average MoCA scores in old males and old females were 27.00

(SD=0.67) and 28.28 (SD=2.10) respectively. The mean PRMQ scores in old males and

old females were 36.30 (SD=8.50) and 39.09 (SD=9.99) respectively (See figure 4)

In older adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference between old

males and old females in BDI, MoCA and PRMQ scores (U=281.00, p=0.46, n2 =0.01),

(U=246.00, p=0.16, n2 =0.04) and (U=263.00, p=0.28, n2 =0.02) respectively.

Young adults

The average BDI score in young males was 8.24 (SD=8.32) whereas that for young

females was 12.00 (SD=8.69). The mean MoCA score was 27.71 (SD=2.12) in young

males while that for young females was 27.71 (SD=2.05). The average PRMQ score in

young males was 38.76 (SD=8.40) whereas that for young females was 41.00 (SD=10.57).

CHAPTER TWO 21

In young adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference in BDI,

MoCA and PRMQ scores between young males and young females (U=235.00, p=0.09,

n2 =0.06), (U=323.00, p=0.96, n2 =0.00) and (U=287.50, p=0.48, n2 =0.01) respectively.

Figure 4: Box plot of mean for (BDI, PRMQ, MoCA scores) in old males and females

Correlation Analysis

This study employed Spearman’s correlation to determine the strength and direction of

relationship between variables.

Correlation based on age

Correlation between anxiety levels and age

There is a negative significant correlation between the trait anxiety and age in the old

group (r=-.31, p=0.26); this shows that the age and the trait anxiety are inversely related

among the old adults. There is no significant correlation between age and other aspects

of anxiety levels among older adults; in addition, there is no any significant correlation

between the aspects of anxiety levels and the young group. Anxiety in general decreases

with age. With older age, one becomes internally focused and they increasingly focused

on integrity, wisdom and making peace with one another.

Correlation between BAI, SAI and TAI levels

In young adults, Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference in BDI,

MoCA and PRMQ scores between young males and young females (U=235.00, p=0.09,

n2 =0.06), (U=323.00, p=0.96, n2 =0.00) and (U=287.50, p=0.48, n2 =0.01) respectively.

Figure 4: Box plot of mean for (BDI, PRMQ, MoCA scores) in old males and females

Correlation Analysis

This study employed Spearman’s correlation to determine the strength and direction of

relationship between variables.

Correlation based on age

Correlation between anxiety levels and age

There is a negative significant correlation between the trait anxiety and age in the old

group (r=-.31, p=0.26); this shows that the age and the trait anxiety are inversely related

among the old adults. There is no significant correlation between age and other aspects

of anxiety levels among older adults; in addition, there is no any significant correlation

between the aspects of anxiety levels and the young group. Anxiety in general decreases

with age. With older age, one becomes internally focused and they increasingly focused

on integrity, wisdom and making peace with one another.

Correlation between BAI, SAI and TAI levels

CHAPTER TWO 22

Assessing correlation among the instruments of cognition is done for accuracy. The

hypothesis is that all the desired results should be arrived at using various instruments

without much deviation from each other. There is a positive significant correlation

between TAI anxiety and BAI in the older group, (r=.33, p=0.02). There is also a

positive significant correlation between SAI and TAI in the older group, (r=.72, p=.000).

In addition, there is a positive significant correlation between BAI and STAI in the

younger group, (r=.62, p=.000) and (r=.67 p=.000), as well as there is a positive

significant correlation between SAI and TAI in the younger group, (r=.78, p=.000).

Correlation between anxiety levels and years of education

There are no significant correlations between the years of education and aspects of

anxiety levels in both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and handedness

There are no significant correlations between the handedness and the aspects of anxiety

levels in both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and eyesight/vision

There are no significant correlations between the vision and aspects of anxiety levels in

both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and depression

There is significant positive correlation between depression and state anxiety in older

adults (r=.36, p=0.01); this is a positive relationship. Moreover, depression and trait

anxiety have a positive significant relationship in older adults (r=.40, p=0.00). There is a

significant positive relationship between state anxiety and depression in the young

Assessing correlation among the instruments of cognition is done for accuracy. The

hypothesis is that all the desired results should be arrived at using various instruments

without much deviation from each other. There is a positive significant correlation

between TAI anxiety and BAI in the older group, (r=.33, p=0.02). There is also a

positive significant correlation between SAI and TAI in the older group, (r=.72, p=.000).

In addition, there is a positive significant correlation between BAI and STAI in the

younger group, (r=.62, p=.000) and (r=.67 p=.000), as well as there is a positive

significant correlation between SAI and TAI in the younger group, (r=.78, p=.000).

Correlation between anxiety levels and years of education

There are no significant correlations between the years of education and aspects of

anxiety levels in both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and handedness

There are no significant correlations between the handedness and the aspects of anxiety

levels in both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and eyesight/vision

There are no significant correlations between the vision and aspects of anxiety levels in

both young and older adults (p > .05).

Correlation between anxiety levels and depression

There is significant positive correlation between depression and state anxiety in older

adults (r=.36, p=0.01); this is a positive relationship. Moreover, depression and trait

anxiety have a positive significant relationship in older adults (r=.40, p=0.00). There is a

significant positive relationship between state anxiety and depression in the young

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER TWO 23

group (r=.74, p=0.00); also, there is a positive significant correlation between the trait

anxiety and depression in the young group (r=.78, p=0.00). It is therefore very easy to

treat depression and the different types of anxiety as one. Anxiety however, causes

depression (Martin M Antony, Peter J Bieling, & Brian J Cox, 1998).

The correlation between anxiety levels and objective cognitive Function (MoCA)

There is no significant correlation between the levels of anxiety and objective cognitive

function (MoCA) in both the older adults and the young group (p > .05).

The correlation between anxiety levels and subjective memory complaint (PRMQ)

There is a significant positive correlation between the state anxiety and subjective

memory complaint in older adults (r=.32, p=0.00). In addition, the trait anxiety and

subjective memory complaint in older adults have a positive significant correlation

(r=.50, p=.00). There is a significant positive correlation between the subjective memory

complaint and trait anxiety in the younger group (r=.34, p=.01). These positive

correlations indicate that the variables have a uniform relationship; increase in one

variable might result in a significant increase in the other variable. This confirms the fact

that anxiety negatively affects subjective memory, just as in previous studies (Balash, 2012).

Correlations by Gender

The correlation between anxiety levels and gender

There is a significant negative correlation between trait anxiety and age in old males,

(r=-.50, p=0.03); an inverse relationship indicates that an increase in age reduces the

group (r=.74, p=0.00); also, there is a positive significant correlation between the trait

anxiety and depression in the young group (r=.78, p=0.00). It is therefore very easy to

treat depression and the different types of anxiety as one. Anxiety however, causes

depression (Martin M Antony, Peter J Bieling, & Brian J Cox, 1998).

The correlation between anxiety levels and objective cognitive Function (MoCA)

There is no significant correlation between the levels of anxiety and objective cognitive

function (MoCA) in both the older adults and the young group (p > .05).

The correlation between anxiety levels and subjective memory complaint (PRMQ)

There is a significant positive correlation between the state anxiety and subjective

memory complaint in older adults (r=.32, p=0.00). In addition, the trait anxiety and

subjective memory complaint in older adults have a positive significant correlation

(r=.50, p=.00). There is a significant positive correlation between the subjective memory

complaint and trait anxiety in the younger group (r=.34, p=.01). These positive

correlations indicate that the variables have a uniform relationship; increase in one

variable might result in a significant increase in the other variable. This confirms the fact

that anxiety negatively affects subjective memory, just as in previous studies (Balash, 2012).

Correlations by Gender

The correlation between anxiety levels and gender

There is a significant negative correlation between trait anxiety and age in old males,

(r=-.50, p=0.03); an inverse relationship indicates that an increase in age reduces the

CHAPTER TWO 24

trait anxiety, while no significant correlation between age and aspects of anxiety level is

made in old females, young males and young females.

Correlation between BAI, STAI and TAI levels

There is a positive significant correlation between BAI and STAI in old males group,

(r=.45, p=0.046) and (r=.59, p=0.006), because they are close measures of anxiety levels.

There is also a positive significant correlation between STAI and TAI in old males,

(r=.65, p=.002). In addition, there is a positive significant correlation between STAI and

TAI in old females, (r=.79, p=.000). Also, there is a positive significant correlation

between BAI, STAI in the young males, (r=.56, p=.008) and (r=.70 p=.000), as well as

there is as a a positive significant correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety in

the same group, (r=.86, p=.000). There is a positive significant correlation between BAI,

STAI and TAI in the young females, (r=.56, p=.001) and (r=.60, p=.000), as well as a

positive significant correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety in the same

group, (r=.69, p=.000). Any instrument can therefore be used to measure the level of anxiety

in an individual, as they give almost similar results for the same level under test.

The correlation between anxiety levels and years of education

There is no significant correlation between years of education and aspects of anxiety in

old males, old females, young males and young females (p> .05).

The correlation between anxiety levels and handedness

There is no significant correlation between handedness and aspects of anxiety in old

males and females, and young males and females (p > .05).

The correlation between anxiety levels and vision

trait anxiety, while no significant correlation between age and aspects of anxiety level is

made in old females, young males and young females.

Correlation between BAI, STAI and TAI levels

There is a positive significant correlation between BAI and STAI in old males group,

(r=.45, p=0.046) and (r=.59, p=0.006), because they are close measures of anxiety levels.

There is also a positive significant correlation between STAI and TAI in old males,

(r=.65, p=.002). In addition, there is a positive significant correlation between STAI and

TAI in old females, (r=.79, p=.000). Also, there is a positive significant correlation

between BAI, STAI in the young males, (r=.56, p=.008) and (r=.70 p=.000), as well as

there is as a a positive significant correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety in

the same group, (r=.86, p=.000). There is a positive significant correlation between BAI,

STAI and TAI in the young females, (r=.56, p=.001) and (r=.60, p=.000), as well as a

positive significant correlation between state anxiety and trait anxiety in the same

group, (r=.69, p=.000). Any instrument can therefore be used to measure the level of anxiety

in an individual, as they give almost similar results for the same level under test.