Child Care Facility Under Consideration Case Study 2022

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/02

|18

|4951

|34

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: Diseases 1

Diseases

by

Course:

Tutor:

University:

Department:

Date:

Diseases

by

Course:

Tutor:

University:

Department:

Date:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Diseases 2

Planning, implementation and evaluation of childhood obesity prevention initiative in

Sydney, Australia

1.0 Demographic characteristics of the specific child-care facility and surrounding

community

The child-care facility under consideration in this study is the Sydney Cove Children’s Centre in

the Sydney central business district. The child-care centre is a long daycare facility that is

conveniently located in the heart of the city and meets the National Quality Standard. The centre

offers all-inclusive, stress-free childcare and early education experience. There is a spacious

outdoor area for effective play-based learning experiences. It also offers a detailed study program

for children aged from birth to 6 years based on the Australian Government’s Early Years

Learning Framework (EYLF) (Australian Department of Education, 2017). The pre-school

program is implemented by experienced and qualified instructors and emphasizes on language,

literacy, numeracy and social skills that prepare the child for future school life.

Sydney Cove Children’s Centre has specific rooms customized to fit the needs of each child and

to offer the best early learning experience to the child. Nursery rooms are for children aged 0 to 2

years and are of three different types. There is the one for younger babies aged 0-15 months and

for senior nursery environments for children aged 15 months -2 years. These rooms offer private

family breastfeeding rooms, safe and secure outdoor play area that is directly linked to the indoor

play space and catering for the small babies. The rooms are also equipped with sound play music

programs in addition to multiple nurturing experiences that are appropriate for each age such as

sensory activities (Sydney Cove Children’s Centre, n.d.)

The junior preschool room is for children aged 2-3 years and provides a large outdoor play space

that inspires children to be interested in physical activities. The preschool room has football,

yoga and Zumba programs and a variety of learning experiences that foster individuality, fun and

Planning, implementation and evaluation of childhood obesity prevention initiative in

Sydney, Australia

1.0 Demographic characteristics of the specific child-care facility and surrounding

community

The child-care facility under consideration in this study is the Sydney Cove Children’s Centre in

the Sydney central business district. The child-care centre is a long daycare facility that is

conveniently located in the heart of the city and meets the National Quality Standard. The centre

offers all-inclusive, stress-free childcare and early education experience. There is a spacious

outdoor area for effective play-based learning experiences. It also offers a detailed study program

for children aged from birth to 6 years based on the Australian Government’s Early Years

Learning Framework (EYLF) (Australian Department of Education, 2017). The pre-school

program is implemented by experienced and qualified instructors and emphasizes on language,

literacy, numeracy and social skills that prepare the child for future school life.

Sydney Cove Children’s Centre has specific rooms customized to fit the needs of each child and

to offer the best early learning experience to the child. Nursery rooms are for children aged 0 to 2

years and are of three different types. There is the one for younger babies aged 0-15 months and

for senior nursery environments for children aged 15 months -2 years. These rooms offer private

family breastfeeding rooms, safe and secure outdoor play area that is directly linked to the indoor

play space and catering for the small babies. The rooms are also equipped with sound play music

programs in addition to multiple nurturing experiences that are appropriate for each age such as

sensory activities (Sydney Cove Children’s Centre, n.d.)

The junior preschool room is for children aged 2-3 years and provides a large outdoor play space

that inspires children to be interested in physical activities. The preschool room has football,

yoga and Zumba programs and a variety of learning experiences that foster individuality, fun and

Diseases 3

inquisitiveness. The centre also offers a preschool room for children aged 3-5 years which offers

a preschool program taught by qualified early childhood instructors with bachelors’ degree and

are aimed at the acquisition of knowledge, social skills and numeracy to prepare the children for

future schooling (Sydney Cove Children’s Centre, n.d.).

Sydney is the most populous and busiest city of Australia occupied by about five million people.

It has a median age of 35 years and each household has approximately 2.7 members. English

speakers are the majority (27%) followed by Australians (25%), Chinese (10.8%) among others

with Korean (1.4%) and Maltese (1.3%) accounting for the least. Therefore, Sydney is a hub of

several migrant communities with the Indigenous community accounting for 1.5% of the total

population (ABS, 2016).

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016), 52.7% of the population is male and

female are 47.3%. Family statistics show that there are approximately 18,977 families with

approximately 1.5 children in each family with children and 0.2 for all families. There is an

average of 53,316 private residentials with an average people per household of 2. Children aged

0-4 years are approximately 2,983. 35% of the people in Sydney were attending an academic

institution out of which 33.0% were in higher education, 5.8% in primary school and 4.5% in

secondary school. Regarding employment, 60,399 were employees during the 2016 census out of

which 64.7% were in full-time employment, 26.1% were in part-time employment and 5.1%

were unemployed (ABS, 2016).

Based on the above demographic characteristics, Sydney is a very busy city occupied with

families thus necessitating the need for accessible childcare centres such as the Sydney Cove

Children’s Centre. Moreover, city dwellers are a mixture of individuals from different countries

inquisitiveness. The centre also offers a preschool room for children aged 3-5 years which offers

a preschool program taught by qualified early childhood instructors with bachelors’ degree and

are aimed at the acquisition of knowledge, social skills and numeracy to prepare the children for

future schooling (Sydney Cove Children’s Centre, n.d.).

Sydney is the most populous and busiest city of Australia occupied by about five million people.

It has a median age of 35 years and each household has approximately 2.7 members. English

speakers are the majority (27%) followed by Australians (25%), Chinese (10.8%) among others

with Korean (1.4%) and Maltese (1.3%) accounting for the least. Therefore, Sydney is a hub of

several migrant communities with the Indigenous community accounting for 1.5% of the total

population (ABS, 2016).

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016), 52.7% of the population is male and

female are 47.3%. Family statistics show that there are approximately 18,977 families with

approximately 1.5 children in each family with children and 0.2 for all families. There is an

average of 53,316 private residentials with an average people per household of 2. Children aged

0-4 years are approximately 2,983. 35% of the people in Sydney were attending an academic

institution out of which 33.0% were in higher education, 5.8% in primary school and 4.5% in

secondary school. Regarding employment, 60,399 were employees during the 2016 census out of

which 64.7% were in full-time employment, 26.1% were in part-time employment and 5.1%

were unemployed (ABS, 2016).

Based on the above demographic characteristics, Sydney is a very busy city occupied with

families thus necessitating the need for accessible childcare centres such as the Sydney Cove

Children’s Centre. Moreover, city dwellers are a mixture of individuals from different countries

Diseases 4

and cultures. This is important because it determines the language and curriculum to be used in

the childcare centres that doesn’t segregate those from foreign cultures.

1.2 Etiology and epidemiology of overweight and obesity in the target group

1.2.1 Epidemiology

Over 124 million children and teenagers aged 5-19 years worldwide are obese with the incidence

rates (over 20%) being the highest the Caribbean, North Africa, and the Middle East. USA has

the highest prevalence of childhood obesity among the 34 country members of the Organization

for Economic Co-operation and Development with Australia taking the 5th position (Abarca-

Gómez et al., 2017). The incidence of obesity among primary school kids in Australia in 2015

was 22.9%, with obesity accounting for 7.1% (Hardy, King, Espinel, Cosgrove, & Bauman,

2016). The frequency of acute obesity rose in the same age category (Garnett, Baur, Jones, &

Hardy, 2016). The continuous widening gap of socioeconomic imbalances increases the

prevalence rates in children from lower socioeconomic status families (Hardy et al., 2016).

The pervasiveness of obesity and overweight among Indigenous Australian children is much

higher than non-Indigenous children. Research has indicated that Indigenous children residing in

rural parts have minimal incidences of obesity and overweight compared with their counterparts

in the city (Dyer et al., 2016). The incidence of obesity and overweight varies depending on the

race, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. Childhood obesity is on the rise among different races

in the US (Maahs et al., 2014). It is also more common in populations of low socioeconomic

status. Childhood obesity and overweight is significantly determined by hereditary factors.

Obesity and overweight in a single parent predispose the child to obesity three times and up to

fifteen times if both parents are obese (Jiang, Yang, Guo, & Sun, 2013).

An overwhelming increase in childhood obesity has been observed in school-aged children and

early teenagers aged 6-11 years and 12-19 years respectively between 2009 and 2010 (Ogden,

and cultures. This is important because it determines the language and curriculum to be used in

the childcare centres that doesn’t segregate those from foreign cultures.

1.2 Etiology and epidemiology of overweight and obesity in the target group

1.2.1 Epidemiology

Over 124 million children and teenagers aged 5-19 years worldwide are obese with the incidence

rates (over 20%) being the highest the Caribbean, North Africa, and the Middle East. USA has

the highest prevalence of childhood obesity among the 34 country members of the Organization

for Economic Co-operation and Development with Australia taking the 5th position (Abarca-

Gómez et al., 2017). The incidence of obesity among primary school kids in Australia in 2015

was 22.9%, with obesity accounting for 7.1% (Hardy, King, Espinel, Cosgrove, & Bauman,

2016). The frequency of acute obesity rose in the same age category (Garnett, Baur, Jones, &

Hardy, 2016). The continuous widening gap of socioeconomic imbalances increases the

prevalence rates in children from lower socioeconomic status families (Hardy et al., 2016).

The pervasiveness of obesity and overweight among Indigenous Australian children is much

higher than non-Indigenous children. Research has indicated that Indigenous children residing in

rural parts have minimal incidences of obesity and overweight compared with their counterparts

in the city (Dyer et al., 2016). The incidence of obesity and overweight varies depending on the

race, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. Childhood obesity is on the rise among different races

in the US (Maahs et al., 2014). It is also more common in populations of low socioeconomic

status. Childhood obesity and overweight is significantly determined by hereditary factors.

Obesity and overweight in a single parent predispose the child to obesity three times and up to

fifteen times if both parents are obese (Jiang, Yang, Guo, & Sun, 2013).

An overwhelming increase in childhood obesity has been observed in school-aged children and

early teenagers aged 6-11 years and 12-19 years respectively between 2009 and 2010 (Ogden,

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Diseases 5

Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). There is limited research that suggests that the incidence of obesity

and overweight in preschool-aged children has decreased from 13.9% to 8.4% in 2004 and 2011

respectively (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014). Notwithstanding the overall incidence of

obesity and overweight in children in the US, the rate of acute obesity in children of over two

years is still alarming. According to the study by Skinner and Skelton (2014) carried out in 2012,

9.5% of the children were diagnosed with acute obesity (BMI>=120%).

1.2.2 Etiology

Obesity and overweight in children are as a result of an interface among an intricate combination

of aspects that are linked to the setting, heredities and environmental impacts e.g. the

community, institution and the family. The ecological aspects for obesity and overweight in

children are intricate (Mouchacca, Abbott, & Ball, 2013). Studies have shown that emotional and

psychological suffering influence excessive increase in weight in children through maladaptive

managing tactics like consuming food to conquer harmful feelings, control of appetite, and

inflammation (Hemmingsson, 2014; Waters et al., 2011). The dietary conduct in children and the

subsequent increase in the risk of diabetes are linked with dietary patters of the family, and

anxiety (El-Behadli, Sharp, Hughes, Obasi, & Nicklas, 2015). Environmental changes leading to

high food consumption have been associated with risk factors to low energy use such as

inactivity and a lot of time used in phones and television watching. Studies have documented a

link between the time occupied in tv watching in a bedroom of a child and the incidence of

obesity and overweight, (Banfield, Liu, Davis, Chang, & Frazier-Wood, 2016).

The 50% differences in adiposity can be explained by heritable factors. Studies have identified

multiple single-gene flaws associated with obesity. Children diagnosed with genetic syndromes

related to obesity have an initial commencement of obesity and notable features during the

physical assessment that is short stature, retarded development, mental retardation. Mutations in

Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). There is limited research that suggests that the incidence of obesity

and overweight in preschool-aged children has decreased from 13.9% to 8.4% in 2004 and 2011

respectively (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014). Notwithstanding the overall incidence of

obesity and overweight in children in the US, the rate of acute obesity in children of over two

years is still alarming. According to the study by Skinner and Skelton (2014) carried out in 2012,

9.5% of the children were diagnosed with acute obesity (BMI>=120%).

1.2.2 Etiology

Obesity and overweight in children are as a result of an interface among an intricate combination

of aspects that are linked to the setting, heredities and environmental impacts e.g. the

community, institution and the family. The ecological aspects for obesity and overweight in

children are intricate (Mouchacca, Abbott, & Ball, 2013). Studies have shown that emotional and

psychological suffering influence excessive increase in weight in children through maladaptive

managing tactics like consuming food to conquer harmful feelings, control of appetite, and

inflammation (Hemmingsson, 2014; Waters et al., 2011). The dietary conduct in children and the

subsequent increase in the risk of diabetes are linked with dietary patters of the family, and

anxiety (El-Behadli, Sharp, Hughes, Obasi, & Nicklas, 2015). Environmental changes leading to

high food consumption have been associated with risk factors to low energy use such as

inactivity and a lot of time used in phones and television watching. Studies have documented a

link between the time occupied in tv watching in a bedroom of a child and the incidence of

obesity and overweight, (Banfield, Liu, Davis, Chang, & Frazier-Wood, 2016).

The 50% differences in adiposity can be explained by heritable factors. Studies have identified

multiple single-gene flaws associated with obesity. Children diagnosed with genetic syndromes

related to obesity have an initial commencement of obesity and notable features during the

physical assessment that is short stature, retarded development, mental retardation. Mutations in

Diseases 6

the melanocortin 4 receptors are the major single-gene flaw that has been recognized in diabetic

children (Fernandez, Klimentidis, Dulin-Keita, & Casazza, 2012). Epigenetic factors are also

influential in the increase of obesity cases. Such aspects can alter the These factors may alter the

interface of the setting, genetic, and diet in fostering obesity (Chang & Neu, 2015). Endocrine

disorders also contribute to the frequency obesity and overweight. However, they are

accountable for only less than 1% of children and teenagers (Kumar, & Kelly, 2017). Majority of

the children diagnosed with the endocrine disease have increased weight gain and poor linear

development, and short stature.

1.3 Justification of stakeholder group selection

The selected intervention for this study is the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment

for Child Care (NAP SACC). The potential stakeholders include childcare providers, technical

assistance consultants, early care and education professionals, and parents. Childcare providers

will be critical in the implementation phase of the intervention since it is implemented in a

childcare setting and they will be responsible for the assessment of the overall environment. The

technical assistance consultants will also be critical in the development of an action plan to foster

the area of a target. Moreover, the NPA SACC consultants will also deliver routine education

seminars on childhood obesity, healthy diet for children and physical activity for children. The

NAP SACC technical consultants will also offer continuous technical help through individual

visits and follow-up via telephone. They will also be important in the implementation of

scheduled policy, practice and ecological shifts. Early care and educational professionals are

potential stakeholders because they will also offer advisory services on the legal framework

within which the intervention will be implemented. Furthermore, they will be critical in the

the melanocortin 4 receptors are the major single-gene flaw that has been recognized in diabetic

children (Fernandez, Klimentidis, Dulin-Keita, & Casazza, 2012). Epigenetic factors are also

influential in the increase of obesity cases. Such aspects can alter the These factors may alter the

interface of the setting, genetic, and diet in fostering obesity (Chang & Neu, 2015). Endocrine

disorders also contribute to the frequency obesity and overweight. However, they are

accountable for only less than 1% of children and teenagers (Kumar, & Kelly, 2017). Majority of

the children diagnosed with the endocrine disease have increased weight gain and poor linear

development, and short stature.

1.3 Justification of stakeholder group selection

The selected intervention for this study is the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment

for Child Care (NAP SACC). The potential stakeholders include childcare providers, technical

assistance consultants, early care and education professionals, and parents. Childcare providers

will be critical in the implementation phase of the intervention since it is implemented in a

childcare setting and they will be responsible for the assessment of the overall environment. The

technical assistance consultants will also be critical in the development of an action plan to foster

the area of a target. Moreover, the NPA SACC consultants will also deliver routine education

seminars on childhood obesity, healthy diet for children and physical activity for children. The

NAP SACC technical consultants will also offer continuous technical help through individual

visits and follow-up via telephone. They will also be important in the implementation of

scheduled policy, practice and ecological shifts. Early care and educational professionals are

potential stakeholders because they will also offer advisory services on the legal framework

within which the intervention will be implemented. Furthermore, they will be critical in the

Diseases 7

evaluation of adequate physical activity, recommended dietary patterns and recommended BMI

for the children based on their body physiology (Battista et al., 2014).

1.4 Description of the intervention

Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Program

The NAP SACC program is an ecological approach to implement changes in the dietary and

physical activity events, procedures and structural setting of the child-care centers with a

particular focus on attaining a healthy weight for young children. The goal of the program is to

foster appropriated dietary practices and activity among the children in childcare and preschool

environment. The NAP SACC consists of multiple elements such as self-assessment tool,

ongoing education seminars, joint action planning and technical assistance equipment. The

design of the intervention is such that it was to be implemented through an established

organization of public health experts that are licensed nurses and health instructors trained as

NAP SACC consultants (Martin, Martin, Cook, Knaus, & O'Rourke, 2015). The program is

expected to take six months for intervention with the following main steps:

1. Childcare centre directors and major employees complete the individual evaluation tool

to evaluate centre dietary patterns and physical activity procedures, norms and general

setting.

2. The NAP SACC counsellors collaborate with the centre's administration to design an an

implementation guide to advance no less than three areas of target previously identified

through the individual evaluation tool.

3. The NAP SACC counsellors offer five NAP SACC ongoing literacy seminars to centre

employees on i) childhood obesity and overweight, 2) recommended dietary patterns for

evaluation of adequate physical activity, recommended dietary patterns and recommended BMI

for the children based on their body physiology (Battista et al., 2014).

1.4 Description of the intervention

Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Program

The NAP SACC program is an ecological approach to implement changes in the dietary and

physical activity events, procedures and structural setting of the child-care centers with a

particular focus on attaining a healthy weight for young children. The goal of the program is to

foster appropriated dietary practices and activity among the children in childcare and preschool

environment. The NAP SACC consists of multiple elements such as self-assessment tool,

ongoing education seminars, joint action planning and technical assistance equipment. The

design of the intervention is such that it was to be implemented through an established

organization of public health experts that are licensed nurses and health instructors trained as

NAP SACC consultants (Martin, Martin, Cook, Knaus, & O'Rourke, 2015). The program is

expected to take six months for intervention with the following main steps:

1. Childcare centre directors and major employees complete the individual evaluation tool

to evaluate centre dietary patterns and physical activity procedures, norms and general

setting.

2. The NAP SACC counsellors collaborate with the centre's administration to design an an

implementation guide to advance no less than three areas of target previously identified

through the individual evaluation tool.

3. The NAP SACC counsellors offer five NAP SACC ongoing literacy seminars to centre

employees on i) childhood obesity and overweight, 2) recommended dietary patterns for

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Diseases 8

children 3) active lifestyle, 4) individual welfare of employees , and 5) incorporating

families

4. NAP SACC counsellors offer continuous technical aid, through personal visits and via

mobile follow-up, to promote the actualization of an established procedure, exercise, and

ecological variations

5. The centres then complete a follow-up individual evaluation tool to assess the changes

previously implemented over 6 months.

(Martin et al., 2015)

1.4.1 Development of the individual evaluation tool and seminars

A self-assessment instrument is important in improving childcare settings more than other

existing rating scales for childcare quality. Moreover, the individual evaluation tool will be

important in focusing on the areas of interest and provide more workable advancements through

willful involvement and self-initiated change. Moreover, centre-directed evaluation permits a

childcare environment to assess their dietary pattern and physical activity settings without

consequences from the governing agencies. Furthermore, the tool is fast and easy, and it is made

to permit the childcare centre administrator to respond to queries with the help of the major

employee. The initial evaluation will consist of 44 questions obtained from 9 nutrition and 6

physical activity areas with previous evidence-based or professional-based association to

childhood obesity (Blaine et al., 2015).

1.4.2 Barriers to implementation

The implementation of the NAP SACC program is likely to be affected by several barriers. One

of the potential barriers to its implementation is the reliance on NAP SACC consultants to recruit

early care and education program administrators and to help them with implementation. The

provision of the local technical assistance is a significant implementation strategy but the un-

children 3) active lifestyle, 4) individual welfare of employees , and 5) incorporating

families

4. NAP SACC counsellors offer continuous technical aid, through personal visits and via

mobile follow-up, to promote the actualization of an established procedure, exercise, and

ecological variations

5. The centres then complete a follow-up individual evaluation tool to assess the changes

previously implemented over 6 months.

(Martin et al., 2015)

1.4.1 Development of the individual evaluation tool and seminars

A self-assessment instrument is important in improving childcare settings more than other

existing rating scales for childcare quality. Moreover, the individual evaluation tool will be

important in focusing on the areas of interest and provide more workable advancements through

willful involvement and self-initiated change. Moreover, centre-directed evaluation permits a

childcare environment to assess their dietary pattern and physical activity settings without

consequences from the governing agencies. Furthermore, the tool is fast and easy, and it is made

to permit the childcare centre administrator to respond to queries with the help of the major

employee. The initial evaluation will consist of 44 questions obtained from 9 nutrition and 6

physical activity areas with previous evidence-based or professional-based association to

childhood obesity (Blaine et al., 2015).

1.4.2 Barriers to implementation

The implementation of the NAP SACC program is likely to be affected by several barriers. One

of the potential barriers to its implementation is the reliance on NAP SACC consultants to recruit

early care and education program administrators and to help them with implementation. The

provision of the local technical assistance is a significant implementation strategy but the un-

Diseases 9

availability of consultants, the necessity for distinct training, and the insufficient funds for

consultant time implies that NAP SACC program will not be available most of the times or could

only be promoted in a few early cares and education programs, Evers, Davis, Maalouf, & Griffin,

2014).

Another potential barrier is the possibility of slow internet service which is common in rural

areas in which the childcare centres are found. This is also associated with computer illiteracy.

The program requires internet connectivity and computer literacy without which it would be

impossible to implement it. This will necessitate the need for computer training, thus increasing

the cost of implementation. Studies on the effectiveness of the NAP SACC program have

generally received limited attention to date (Ward, Vaughn, Mazzucca, & Burney, 2017)

especially in programs associated with child nutrition. Some early care and education (ECE)

technical assistance agencies are likely to be reluctant to the use of online tools with ECE

programs due to their perception of the limited computer knowledge and internet skills among

ECE providers.

1.5 Outline of the communication strategy

The communication strategy for NAP SACC intervention program will include 7 steps namely

identification of stakeholders, identification of stakeholder prospects, identify the

communication appropriate for communicating stakeholder expectations, identify time-frame or

frequency of communication, determine the preferred communication channel of the stakeholder,

assign communication duties and document items.

1. Identification of stakeholders: The potential stakeholders for the intervention include

parents, director and staff of childcare centre, early care and education professionals.

availability of consultants, the necessity for distinct training, and the insufficient funds for

consultant time implies that NAP SACC program will not be available most of the times or could

only be promoted in a few early cares and education programs, Evers, Davis, Maalouf, & Griffin,

2014).

Another potential barrier is the possibility of slow internet service which is common in rural

areas in which the childcare centres are found. This is also associated with computer illiteracy.

The program requires internet connectivity and computer literacy without which it would be

impossible to implement it. This will necessitate the need for computer training, thus increasing

the cost of implementation. Studies on the effectiveness of the NAP SACC program have

generally received limited attention to date (Ward, Vaughn, Mazzucca, & Burney, 2017)

especially in programs associated with child nutrition. Some early care and education (ECE)

technical assistance agencies are likely to be reluctant to the use of online tools with ECE

programs due to their perception of the limited computer knowledge and internet skills among

ECE providers.

1.5 Outline of the communication strategy

The communication strategy for NAP SACC intervention program will include 7 steps namely

identification of stakeholders, identification of stakeholder prospects, identify the

communication appropriate for communicating stakeholder expectations, identify time-frame or

frequency of communication, determine the preferred communication channel of the stakeholder,

assign communication duties and document items.

1. Identification of stakeholders: The potential stakeholders for the intervention include

parents, director and staff of childcare centre, early care and education professionals.

Diseases 10

2. Identification of stakeholder prospects: the possible expectations of the potential

stakeholders include healthy eating, physical activity and reduced sedentary behaviour, program

recognition, implementation of nutritional guidelines, healthy weight and improved quality of

life.

3. Determining appropriate communication messages to the stakeholders: the messages for

each intervention level will be communicated separately depending on the assessment of the

indicators. For instance, at the individual assessment level, the reports will consist of the need

and willingness of the centre to adopt the proposed changes.

4. Time-frame or frequency of communication: the intervention will take 6 months but

communication for each level of implementation will be made to the relevant stakeholders after 2

months. This is to ensure that the relevant parties of interest are updated on the progress of the

implementation

5. Communication Channel: the major channels of communication will include emails and any

preferred social media platform by the stakeholder

6. Communication responsibility: a designated secretary will be responsible for all

communications

7. Documentation: All communications and partial or complete reports will be documented in

the acceptable formats and templates

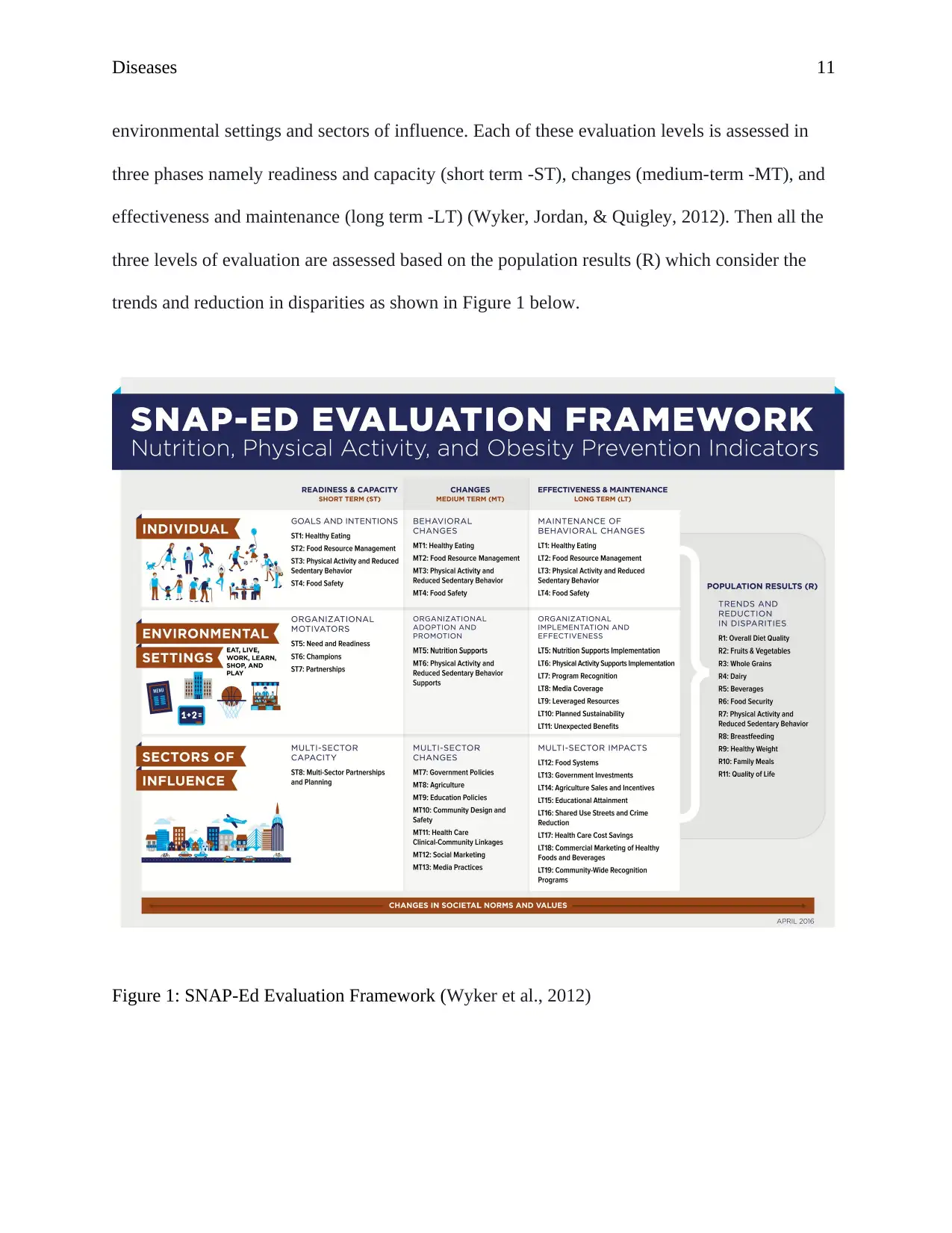

1.6 Outline of the evaluation framework

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-ED) Evaluation Framework

will be used in evaluating the implementation of the NAP SACC intervention program. The

SNAP-ED framework utilizes the social-ecological model to the nutrition, physical activity and

prevention of obesity. The Framework has three levels of evaluation namely individual,

2. Identification of stakeholder prospects: the possible expectations of the potential

stakeholders include healthy eating, physical activity and reduced sedentary behaviour, program

recognition, implementation of nutritional guidelines, healthy weight and improved quality of

life.

3. Determining appropriate communication messages to the stakeholders: the messages for

each intervention level will be communicated separately depending on the assessment of the

indicators. For instance, at the individual assessment level, the reports will consist of the need

and willingness of the centre to adopt the proposed changes.

4. Time-frame or frequency of communication: the intervention will take 6 months but

communication for each level of implementation will be made to the relevant stakeholders after 2

months. This is to ensure that the relevant parties of interest are updated on the progress of the

implementation

5. Communication Channel: the major channels of communication will include emails and any

preferred social media platform by the stakeholder

6. Communication responsibility: a designated secretary will be responsible for all

communications

7. Documentation: All communications and partial or complete reports will be documented in

the acceptable formats and templates

1.6 Outline of the evaluation framework

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-ED) Evaluation Framework

will be used in evaluating the implementation of the NAP SACC intervention program. The

SNAP-ED framework utilizes the social-ecological model to the nutrition, physical activity and

prevention of obesity. The Framework has three levels of evaluation namely individual,

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Diseases 11

environmental settings and sectors of influence. Each of these evaluation levels is assessed in

three phases namely readiness and capacity (short term -ST), changes (medium-term -MT), and

effectiveness and maintenance (long term -LT) (Wyker, Jordan, & Quigley, 2012). Then all the

three levels of evaluation are assessed based on the population results (R) which consider the

trends and reduction in disparities as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: SNAP-Ed Evaluation Framework (Wyker et al., 2012)

environmental settings and sectors of influence. Each of these evaluation levels is assessed in

three phases namely readiness and capacity (short term -ST), changes (medium-term -MT), and

effectiveness and maintenance (long term -LT) (Wyker, Jordan, & Quigley, 2012). Then all the

three levels of evaluation are assessed based on the population results (R) which consider the

trends and reduction in disparities as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: SNAP-Ed Evaluation Framework (Wyker et al., 2012)

Diseases 12

Individual-level

The SNAP-ED framework aims at determining the degree to which the intervention improves

and maintains healthy eating and physical activity behaviours of the participants. The short-term

indicators are the initial steps towards behaviour change, for example, the participants’ goals and

motives regarding nutrition and physical activity. Behaviour change in the medium term is

determined using multiple parameters such as healthy eating, decrease in sedentary behaviour,

physical activity and the management of food resources- based on the area of focus of the

intervention. For pre-school children, the study will use the Visually-Enhanced Food Behavior

Checklist before and after implementation. The long-term indicators evaluate the sustainability

of the observed and recorded behaviour changes within 6 months after the successful completion

of the program (Ward, Vaughn, Mazzucca, & Burney, 2017).

Environmental level

This evaluation level aims at determining the degree to which the intervention create and

maintain access and plea for healthy eating and physical activity options in the environment

where the participants eat, learn, play, and reside. The short-term indicators include the need and

readiness of the childcare centre in addition to the readiness of the employees to accept and

embrace changes. Medium-term indicators assess the childcare centres adoption of policies,

systems, and environments (PSEs) for instance, integrating physical activity breaks during the

routine class sessions in addition to the number of learners reached by the changes. Long-term

indicators assess the implementation and if the significant elements for successful results are

present such as parent involvement and training. Studies in the effectiveness of SNAP-ED

Individual-level

The SNAP-ED framework aims at determining the degree to which the intervention improves

and maintains healthy eating and physical activity behaviours of the participants. The short-term

indicators are the initial steps towards behaviour change, for example, the participants’ goals and

motives regarding nutrition and physical activity. Behaviour change in the medium term is

determined using multiple parameters such as healthy eating, decrease in sedentary behaviour,

physical activity and the management of food resources- based on the area of focus of the

intervention. For pre-school children, the study will use the Visually-Enhanced Food Behavior

Checklist before and after implementation. The long-term indicators evaluate the sustainability

of the observed and recorded behaviour changes within 6 months after the successful completion

of the program (Ward, Vaughn, Mazzucca, & Burney, 2017).

Environmental level

This evaluation level aims at determining the degree to which the intervention create and

maintain access and plea for healthy eating and physical activity options in the environment

where the participants eat, learn, play, and reside. The short-term indicators include the need and

readiness of the childcare centre in addition to the readiness of the employees to accept and

embrace changes. Medium-term indicators assess the childcare centres adoption of policies,

systems, and environments (PSEs) for instance, integrating physical activity breaks during the

routine class sessions in addition to the number of learners reached by the changes. Long-term

indicators assess the implementation and if the significant elements for successful results are

present such as parent involvement and training. Studies in the effectiveness of SNAP-ED

Diseases 13

interventions in cities reported improvement in physical activity scores of the school-going

children (Mehtälä, Sääkslahti, Inkinen, & Poskiparta, 2014).

Sectors of influence

The sector of influence level of assessment evaluates the degree to which the intervention

collaborates with other stakeholders both in the private and public sector to mutually impact long

term healthy eating and physical activity level in the most vulnerable communities. An intricate

of factors that lead to chronic diseases for instance food insecurity and overweight among others

require a wider frame. The short-term indicator aims at assessing the quality of multi-sector

collaborations that are dealing with changes in nutrition or physical activity. The intervention is

assessed on the nature of partners such as agriculture, media, food industry among others to

increase accessibility to healthy foods and establish settings that are favourable to active lives

(Ward et al., 2017).

Population results

The assessment of the population results is aimed at determining the degree to which the

intervention helps attain the standard recommendations by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

(DGA) and the World Health Organization. The population results are measured based on the

trends and reduction in disparities. The specific parameters used include overall diet quality,

whole grains, healthy weight, food security, physical activity and reduced sedentary lifestyle

among others (Ward et al., 2017).

interventions in cities reported improvement in physical activity scores of the school-going

children (Mehtälä, Sääkslahti, Inkinen, & Poskiparta, 2014).

Sectors of influence

The sector of influence level of assessment evaluates the degree to which the intervention

collaborates with other stakeholders both in the private and public sector to mutually impact long

term healthy eating and physical activity level in the most vulnerable communities. An intricate

of factors that lead to chronic diseases for instance food insecurity and overweight among others

require a wider frame. The short-term indicator aims at assessing the quality of multi-sector

collaborations that are dealing with changes in nutrition or physical activity. The intervention is

assessed on the nature of partners such as agriculture, media, food industry among others to

increase accessibility to healthy foods and establish settings that are favourable to active lives

(Ward et al., 2017).

Population results

The assessment of the population results is aimed at determining the degree to which the

intervention helps attain the standard recommendations by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans

(DGA) and the World Health Organization. The population results are measured based on the

trends and reduction in disparities. The specific parameters used include overall diet quality,

whole grains, healthy weight, food security, physical activity and reduced sedentary lifestyle

among others (Ward et al., 2017).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Diseases 14

References

Abarca-Gómez, L., Abdeen, Z. A., Hamid, Z. A., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M., Acosta-Cazares, B.,

Acuin, C., ... & Agyemang, C. (2017). Worldwide trends in body-mass index,

underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416

population-based measurement studies in 128· 9 million children, adolescents, and

adults. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2627-2642.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016). 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved from

https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/

quickstat/SED10080

Australian Department of Education. (2017). Early Years Learning Framework. Retrieved from

https://www.education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework-0

Banfield, E. C., Liu, Y., Davis, J. S., Chang, S., & Frazier-Wood, A. C. (2016). Poor adherence

to US dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in the national health and nutrition

examination survey population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics, 116(1), 21-27.

Battista, R. A., Oakley, H., Weddell, M. S., Mudd, L. M., Greene, J. B., & West, S. T. (2014).

Improving the physical activity and nutrition environment through self-assessment (NAP

SACC) in rural area child care centers in North Carolina. Preventive medicine, 67, S10-

S16.

Blaine, R. E., Davison, K. K., Hesketh, K., Taveras, E. M., Gillman, M. W., & Benjamin Neelon,

References

Abarca-Gómez, L., Abdeen, Z. A., Hamid, Z. A., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M., Acosta-Cazares, B.,

Acuin, C., ... & Agyemang, C. (2017). Worldwide trends in body-mass index,

underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416

population-based measurement studies in 128· 9 million children, adolescents, and

adults. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2627-2642.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016). 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved from

https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/

quickstat/SED10080

Australian Department of Education. (2017). Early Years Learning Framework. Retrieved from

https://www.education.gov.au/early-years-learning-framework-0

Banfield, E. C., Liu, Y., Davis, J. S., Chang, S., & Frazier-Wood, A. C. (2016). Poor adherence

to US dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in the national health and nutrition

examination survey population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics, 116(1), 21-27.

Battista, R. A., Oakley, H., Weddell, M. S., Mudd, L. M., Greene, J. B., & West, S. T. (2014).

Improving the physical activity and nutrition environment through self-assessment (NAP

SACC) in rural area child care centers in North Carolina. Preventive medicine, 67, S10-

S16.

Blaine, R. E., Davison, K. K., Hesketh, K., Taveras, E. M., Gillman, M. W., & Benjamin Neelon,

Diseases 15

S. E. (2015). Child care provider adherence to infant and toddler feeding

recommendations: findings from the Baby Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-

Assessment for Child Care (Baby NAP SACC) Study. Childhood obesity, 11(3), 304-

313.

Chang, L., & Neu, J. (2015). Early factors leading to later obesity: interactions of the

microbiome, epigenome, and nutrition. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent

health care, 45(5), 134-142.

Dyer, S. M., Gomersall, J. S., Smithers, L. G., Davy, C., Coleman, D. T., & Street, J. M. (2017).

Prevalence and characteristics of overweight and obesity in indigenous Australian

children: a systematic review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 57(7), 1365-

1376.

El-Behadli, A. F., Sharp, C., Hughes, S. O., Obasi, E. M., & Nicklas, T. A. (2015). Maternal

depression, stress and feeding styles: towards a framework for theory and research in

child obesity. British journal of nutrition, 113(S1), S55-S71.

Fernandez, J. R., Klimentidis, Y. C., Dulin-Keita, A., & Casazza, K. (2012). Genetic influences

in childhood obesity: recent progress and recommendations for experimental

designs. International Journal of Obesity, 479.

Garnett, S. P., Baur, L. A., Jones, A. M., & Hardy, L. L. (2016). Trends in the prevalence of

morbid and severe obesity in Australian children aged 7-15 years, 1985-2012. PloS

one, 11(5), e0154879.

S. E. (2015). Child care provider adherence to infant and toddler feeding

recommendations: findings from the Baby Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-

Assessment for Child Care (Baby NAP SACC) Study. Childhood obesity, 11(3), 304-

313.

Chang, L., & Neu, J. (2015). Early factors leading to later obesity: interactions of the

microbiome, epigenome, and nutrition. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent

health care, 45(5), 134-142.

Dyer, S. M., Gomersall, J. S., Smithers, L. G., Davy, C., Coleman, D. T., & Street, J. M. (2017).

Prevalence and characteristics of overweight and obesity in indigenous Australian

children: a systematic review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 57(7), 1365-

1376.

El-Behadli, A. F., Sharp, C., Hughes, S. O., Obasi, E. M., & Nicklas, T. A. (2015). Maternal

depression, stress and feeding styles: towards a framework for theory and research in

child obesity. British journal of nutrition, 113(S1), S55-S71.

Fernandez, J. R., Klimentidis, Y. C., Dulin-Keita, A., & Casazza, K. (2012). Genetic influences

in childhood obesity: recent progress and recommendations for experimental

designs. International Journal of Obesity, 479.

Garnett, S. P., Baur, L. A., Jones, A. M., & Hardy, L. L. (2016). Trends in the prevalence of

morbid and severe obesity in Australian children aged 7-15 years, 1985-2012. PloS

one, 11(5), e0154879.

Diseases 16

Hardy, L. L., King, L., Espinel, P., Cosgrove, C., & Bauman, A. (2016). NSW schools physical

activity and nutrition survey (SPANS) 2010: Full Report. 2011. Sydney: NSW Ministry of

Health, 1-387.

Hemmingsson, E. (2014). A new model of the role of psychological and emotional distress in

promoting obesity: conceptual review with implications for treatment and

prevention. Obesity Reviews, 15(9), 769-779.

Jiang, M. H., Yang, Y., Guo, X. F., & Sun, Y. X. (2013). Association between child and

adolescent obesity and parental weight status: a cross-sectional study from rural North

China. Journal of International Medical Research, 41(4), 1326-1332.

Kumar, S., & Kelly, A. S. (2017, February). Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology,

etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. In Mayo Clinic

Proceedings (Vol. 92, No. 2, pp. 251-265). Elsevier.

Lyn, R., Evers, S., Davis, J., Maalouf, J., & Griffin, M. (2014). Barriers and supports to

implementing a nutrition and physical activity intervention in child care: directors'

perspectives. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 46(3), 171-180.

Maahs, D. M., Daniels, S. R., De Ferranti, S. D., Dichek, H. L., Flynn, J., Goldstein, B. I., ... &

Quinn, L. (2014). Cardiovascular disease risk factors in youth with diabetes mellitus: a

scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 130(17), 1532-

1558.

Martin, S. L., Martin, M. W., Cook, B., Knaus, R., & O'Rourke, K. (2015). Notes from the field:

Hardy, L. L., King, L., Espinel, P., Cosgrove, C., & Bauman, A. (2016). NSW schools physical

activity and nutrition survey (SPANS) 2010: Full Report. 2011. Sydney: NSW Ministry of

Health, 1-387.

Hemmingsson, E. (2014). A new model of the role of psychological and emotional distress in

promoting obesity: conceptual review with implications for treatment and

prevention. Obesity Reviews, 15(9), 769-779.

Jiang, M. H., Yang, Y., Guo, X. F., & Sun, Y. X. (2013). Association between child and

adolescent obesity and parental weight status: a cross-sectional study from rural North

China. Journal of International Medical Research, 41(4), 1326-1332.

Kumar, S., & Kelly, A. S. (2017, February). Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology,

etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. In Mayo Clinic

Proceedings (Vol. 92, No. 2, pp. 251-265). Elsevier.

Lyn, R., Evers, S., Davis, J., Maalouf, J., & Griffin, M. (2014). Barriers and supports to

implementing a nutrition and physical activity intervention in child care: directors'

perspectives. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 46(3), 171-180.

Maahs, D. M., Daniels, S. R., De Ferranti, S. D., Dichek, H. L., Flynn, J., Goldstein, B. I., ... &

Quinn, L. (2014). Cardiovascular disease risk factors in youth with diabetes mellitus: a

scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 130(17), 1532-

1558.

Martin, S. L., Martin, M. W., Cook, B., Knaus, R., & O'Rourke, K. (2015). Notes from the field:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Diseases 17

the evaluation of Maine nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care

(NAPSACC) experience. Evaluation & the health professions, 38(1), 140-145.

Mehtälä, M. A. K., Sääkslahti, A. K., Inkinen, M. E., & Poskiparta, M. E. H. (2014). A socio-

ecological approach to physical activity interventions in childcare: a systematic

review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 22.

Mouchacca, J., Abbott, G. R., & Ball, K. (2013). Associations between psychological stress,

eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and body weight among women: a

longitudinal study. BMC public health, 13(1), 828.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2012). Prevalence of obesity and

trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama, 307(5),

483-490.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and

adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama, 311(8), 806-814.

Skinner, A. C., & Skelton, J. A. (2014). Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity

among children in the United States, 1999-2012. JAMA pediatrics, 168(6), 561-566.

Sydney Cove Children’s Centres .(n.d.). About Us. Retrieved from

https://www.earlylearningservices.com.au/centres/childcare-sydney/

Ward, D. S., Vaughn, A. E., Mazzucca, S., & Burney, R. (2017). Translating a child care based

the evaluation of Maine nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care

(NAPSACC) experience. Evaluation & the health professions, 38(1), 140-145.

Mehtälä, M. A. K., Sääkslahti, A. K., Inkinen, M. E., & Poskiparta, M. E. H. (2014). A socio-

ecological approach to physical activity interventions in childcare: a systematic

review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 22.

Mouchacca, J., Abbott, G. R., & Ball, K. (2013). Associations between psychological stress,

eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and body weight among women: a

longitudinal study. BMC public health, 13(1), 828.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2012). Prevalence of obesity and

trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama, 307(5),

483-490.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and

adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama, 311(8), 806-814.

Skinner, A. C., & Skelton, J. A. (2014). Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity

among children in the United States, 1999-2012. JAMA pediatrics, 168(6), 561-566.

Sydney Cove Children’s Centres .(n.d.). About Us. Retrieved from

https://www.earlylearningservices.com.au/centres/childcare-sydney/

Ward, D. S., Vaughn, A. E., Mazzucca, S., & Burney, R. (2017). Translating a child care based

Diseases 18

intervention for online delivery: development and randomized pilot study of Go

NAPSACC. BMC public health, 17(1), 891.

Waters, E., de Silva‐Sanigorski, A., Burford, B. J., Brown, T., Campbell, K. J., Gao, Y., ... &

Summerbell, C. D. (2011). Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane

database of systematic reviews, (12).

Wyker, B. A., Jordan, P., & Quigley, D. L. (2012). Evaluation of supplemental nutrition

assistance program education: application of behavioral theory and survey

validation. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 44(4), 360-364.

intervention for online delivery: development and randomized pilot study of Go

NAPSACC. BMC public health, 17(1), 891.

Waters, E., de Silva‐Sanigorski, A., Burford, B. J., Brown, T., Campbell, K. J., Gao, Y., ... &

Summerbell, C. D. (2011). Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane

database of systematic reviews, (12).

Wyker, B. A., Jordan, P., & Quigley, D. L. (2012). Evaluation of supplemental nutrition

assistance program education: application of behavioral theory and survey

validation. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 44(4), 360-364.

1 out of 18

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.