Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture and Adaptation Strategies: A Case Study of Nepal

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/08

|17

|3904

|409

AI Summary

This chapter discusses the availability scenario of Food and nutrition security in Nepal with a focus on food availability condition, agriculture structure and performance. It also covers the impacts of climate change on agriculture and adaptation strategies.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change impacts on agriculture and adaptation strategies: A Case Study of Nepal

Name of Student:

Name of College:

Authors Note:

1

Climate change impacts on agriculture and adaptation strategies: A Case Study of Nepal

Name of Student:

Name of College:

Authors Note:

1

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Contents

Chapter 4: Food and Nutrition security in Nepal.............................................................................3

Introduction......................................................................................................................................3

4.1 Food availability condition....................................................................................................3

4.2 Nepal’s agriculture structure and performance......................................................................4

4.3: Food and Nutrition security..................................................................................................6

Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................11

References......................................................................................................................................13

Figures & Tables........................................................................................................................15

2

Contents

Chapter 4: Food and Nutrition security in Nepal.............................................................................3

Introduction......................................................................................................................................3

4.1 Food availability condition....................................................................................................3

4.2 Nepal’s agriculture structure and performance......................................................................4

4.3: Food and Nutrition security..................................................................................................6

Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................11

References......................................................................................................................................13

Figures & Tables........................................................................................................................15

2

CLIMATE CHANGE

Chapter 4: Food and Nutrition security in Nepal

Introduction

According to Wang, Woo-Kyun & Son (2017) the GDP rate of Nepal gets significant

contribution from agriculture which had been reflecting strong growth across South Asia at rate

of over 33% as reported during 2016. Also agriculture sector in Nepal has around 27% arable

land and 18% cultivated land which supports employment of over 60% of population in the

country. Also agriculture sector of Nepal consumes nearly 0.84% of total emery consumption. A

large section of Nepalese population relies on small household cultivation for their living. Like

specific low caste category families in Nepal maintain landholding with shared crop procedure

which does not produce significant quantity of cultivation for agriculture demand. As such there

persists poverty and inadequacy of access to nutrition and food which is expected to rise further

in shadow of current economic downfall scenario of Nepal. Moreover as result of climate change

the monsoons have become unforeseeable in characteristics and most of the time Nepal does not

get sufficient amount of rainfall as compared to earlier years; as such this low rainfall has

resulted to instable and unanticipated produce of crops which has further elevated the issue of

food insecurity in Nepal (Das & Bandyopadhyay 2015). In this chapter availability scenario of

Food and nutrition security in Nepal will be discussed with focus on food availability condition,

agriculture structure and performance.

4.1 Food availability condition

According to Gartaula, Patel, Johnson, Devkota, Khadka & Chaudhary (2017) the produce of

cereals in Nepal has been outmatched due to huge population surge and in reality the population

increase rate has been significantly larger than the rate of production rise in cereal crops since the

time of 1960’s. A contrast of average annual increase rate through decade of population and

production of cereals in Nepal reflects that the only period during which Nepal witnessed

production increase rate of cereal more than their rate of population rise was during 1981-90.

Impressively this was also the time which coincides simultaneously when Nepal was a prominent

importer of cereal produces. But after consecutive decades the production increase rate has

dropped significantly in Nepal. Moreover according to Joshi, Ji & Narayan (2017) rise in

3

Chapter 4: Food and Nutrition security in Nepal

Introduction

According to Wang, Woo-Kyun & Son (2017) the GDP rate of Nepal gets significant

contribution from agriculture which had been reflecting strong growth across South Asia at rate

of over 33% as reported during 2016. Also agriculture sector in Nepal has around 27% arable

land and 18% cultivated land which supports employment of over 60% of population in the

country. Also agriculture sector of Nepal consumes nearly 0.84% of total emery consumption. A

large section of Nepalese population relies on small household cultivation for their living. Like

specific low caste category families in Nepal maintain landholding with shared crop procedure

which does not produce significant quantity of cultivation for agriculture demand. As such there

persists poverty and inadequacy of access to nutrition and food which is expected to rise further

in shadow of current economic downfall scenario of Nepal. Moreover as result of climate change

the monsoons have become unforeseeable in characteristics and most of the time Nepal does not

get sufficient amount of rainfall as compared to earlier years; as such this low rainfall has

resulted to instable and unanticipated produce of crops which has further elevated the issue of

food insecurity in Nepal (Das & Bandyopadhyay 2015). In this chapter availability scenario of

Food and nutrition security in Nepal will be discussed with focus on food availability condition,

agriculture structure and performance.

4.1 Food availability condition

According to Gartaula, Patel, Johnson, Devkota, Khadka & Chaudhary (2017) the produce of

cereals in Nepal has been outmatched due to huge population surge and in reality the population

increase rate has been significantly larger than the rate of production rise in cereal crops since the

time of 1960’s. A contrast of average annual increase rate through decade of population and

production of cereals in Nepal reflects that the only period during which Nepal witnessed

production increase rate of cereal more than their rate of population rise was during 1981-90.

Impressively this was also the time which coincides simultaneously when Nepal was a prominent

importer of cereal produces. But after consecutive decades the production increase rate has

dropped significantly in Nepal. Moreover according to Joshi, Ji & Narayan (2017) rise in

3

CLIMATE CHANGE

population had reflected a fall only during 2001-08 but yet it is much larger than their cereal rate

of increase and value of net cereal imports reflects a growing trend during the period. Further it

is observed that Nepal has become a net importer of fruits & vegetables since period of mid 90’s

and this shows that the demand for fruits and vegetable have been rising within Nepal but the

rise in domestic produce has not been capable enough to meet this demand. Also it has been

found that there is significant elevation in imports and notable drop in export of cereals and

fruits, vegetable during recent years specifically since 2000 onwards. Though this time coincides

with period of civil instability within Nepal so an in-depth evaluation is needed before inferring

if there is any direct association between the pattern observed previously in exports/imports and

the domestic political condition in Nepal.

According to Byg & Herslund (2016) although Nepal’s domestic generation of cereals as seen in

whole has not been matching with their rise in population within the nation but their per capita

availability of cereals does not reflect concerning fall and has in actuality drifted around 170 kg

per capita per year since the time of 90’s. Import of cereals is eventually the reasoning for

continuing a high availability which has been probable to Nepal’s liberal trade policies. The

tariff of agricultural products has been the lowest within South Asia since 2002 with no tariffs

charged on staples and no quantitative constraints on agricultural products. Although import of

cereals have eventually elevated, Nepal’s import dependency ratio had not been very alerting as

it reached just to 3.5% of overall domestic availability in 2007. While in context to value fruits

and vegetable form a greater share of Nepal’s imports compared to the cereals with fruits and

vegetables consisting of 22.8% of overall agriculture imports since 2007.

4.2 Nepal’s agriculture structure and performance

As observed earlier the contribution of agriculture in GDP of Nepal has relatively increased with

a considerable improvement rate as contrasted to other South Asian nations, which in 2015-16

was nearly 33% of total GDP of Nepal. However both Gross domestic product and GDPA in

Nepal reflects large variations. But in general the GDP and GDPA are likely to project a trend

which reflects the degree that determines agricultural sector of Nepal an overall driver of their

economic stability and development (Sada, Shrestha, Shukla & Melsen (2014) to interpret

performance of agriculture sector in this section the main sub factors of agriculture in Nepal have

been examined. According to Shah, Tachamo, Sharma, Haase, Jähnig & Pauls (2015) the value

4

population had reflected a fall only during 2001-08 but yet it is much larger than their cereal rate

of increase and value of net cereal imports reflects a growing trend during the period. Further it

is observed that Nepal has become a net importer of fruits & vegetables since period of mid 90’s

and this shows that the demand for fruits and vegetable have been rising within Nepal but the

rise in domestic produce has not been capable enough to meet this demand. Also it has been

found that there is significant elevation in imports and notable drop in export of cereals and

fruits, vegetable during recent years specifically since 2000 onwards. Though this time coincides

with period of civil instability within Nepal so an in-depth evaluation is needed before inferring

if there is any direct association between the pattern observed previously in exports/imports and

the domestic political condition in Nepal.

According to Byg & Herslund (2016) although Nepal’s domestic generation of cereals as seen in

whole has not been matching with their rise in population within the nation but their per capita

availability of cereals does not reflect concerning fall and has in actuality drifted around 170 kg

per capita per year since the time of 90’s. Import of cereals is eventually the reasoning for

continuing a high availability which has been probable to Nepal’s liberal trade policies. The

tariff of agricultural products has been the lowest within South Asia since 2002 with no tariffs

charged on staples and no quantitative constraints on agricultural products. Although import of

cereals have eventually elevated, Nepal’s import dependency ratio had not been very alerting as

it reached just to 3.5% of overall domestic availability in 2007. While in context to value fruits

and vegetable form a greater share of Nepal’s imports compared to the cereals with fruits and

vegetables consisting of 22.8% of overall agriculture imports since 2007.

4.2 Nepal’s agriculture structure and performance

As observed earlier the contribution of agriculture in GDP of Nepal has relatively increased with

a considerable improvement rate as contrasted to other South Asian nations, which in 2015-16

was nearly 33% of total GDP of Nepal. However both Gross domestic product and GDPA in

Nepal reflects large variations. But in general the GDP and GDPA are likely to project a trend

which reflects the degree that determines agricultural sector of Nepal an overall driver of their

economic stability and development (Sada, Shrestha, Shukla & Melsen (2014) to interpret

performance of agriculture sector in this section the main sub factors of agriculture in Nepal have

been examined. According to Shah, Tachamo, Sharma, Haase, Jähnig & Pauls (2015) the value

4

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CLIMATE CHANGE

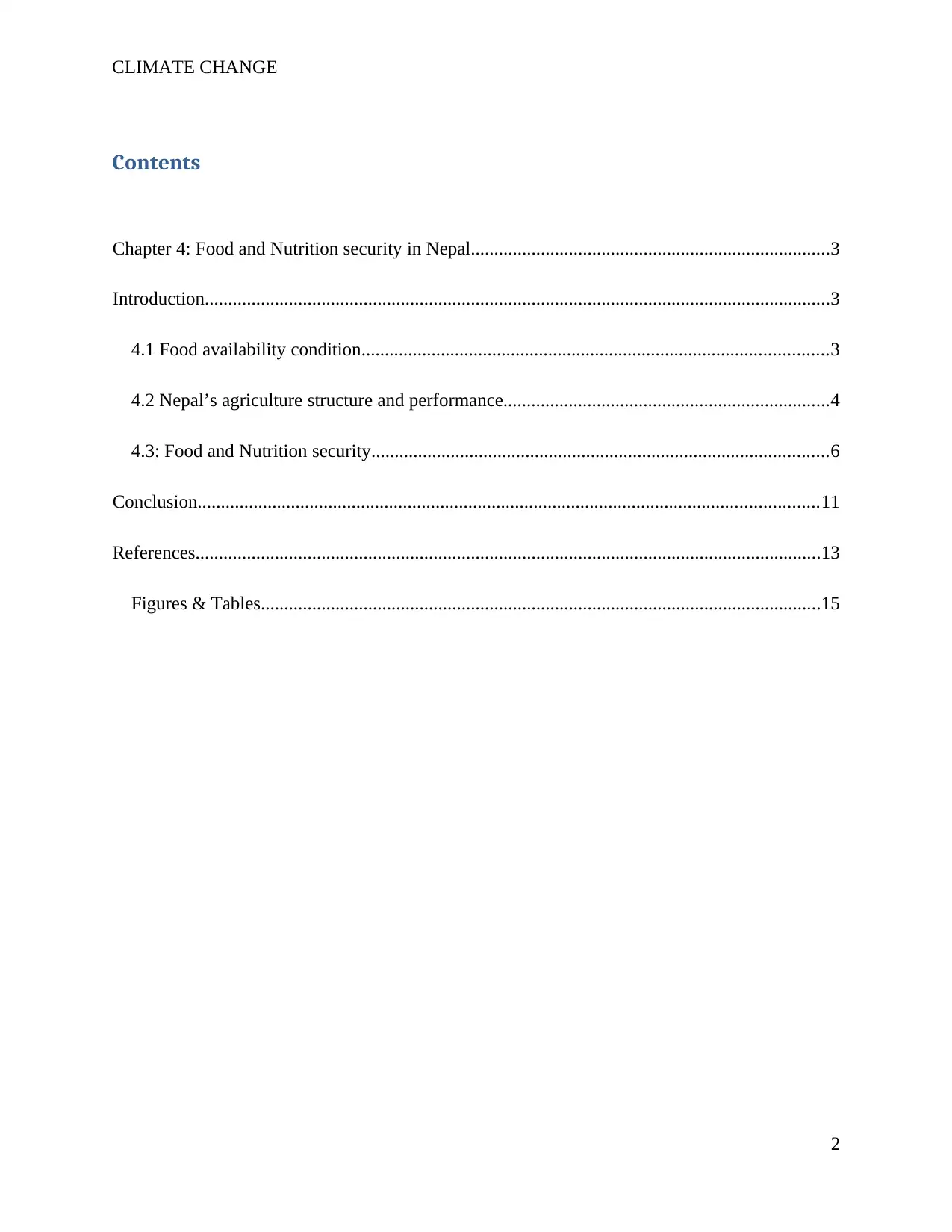

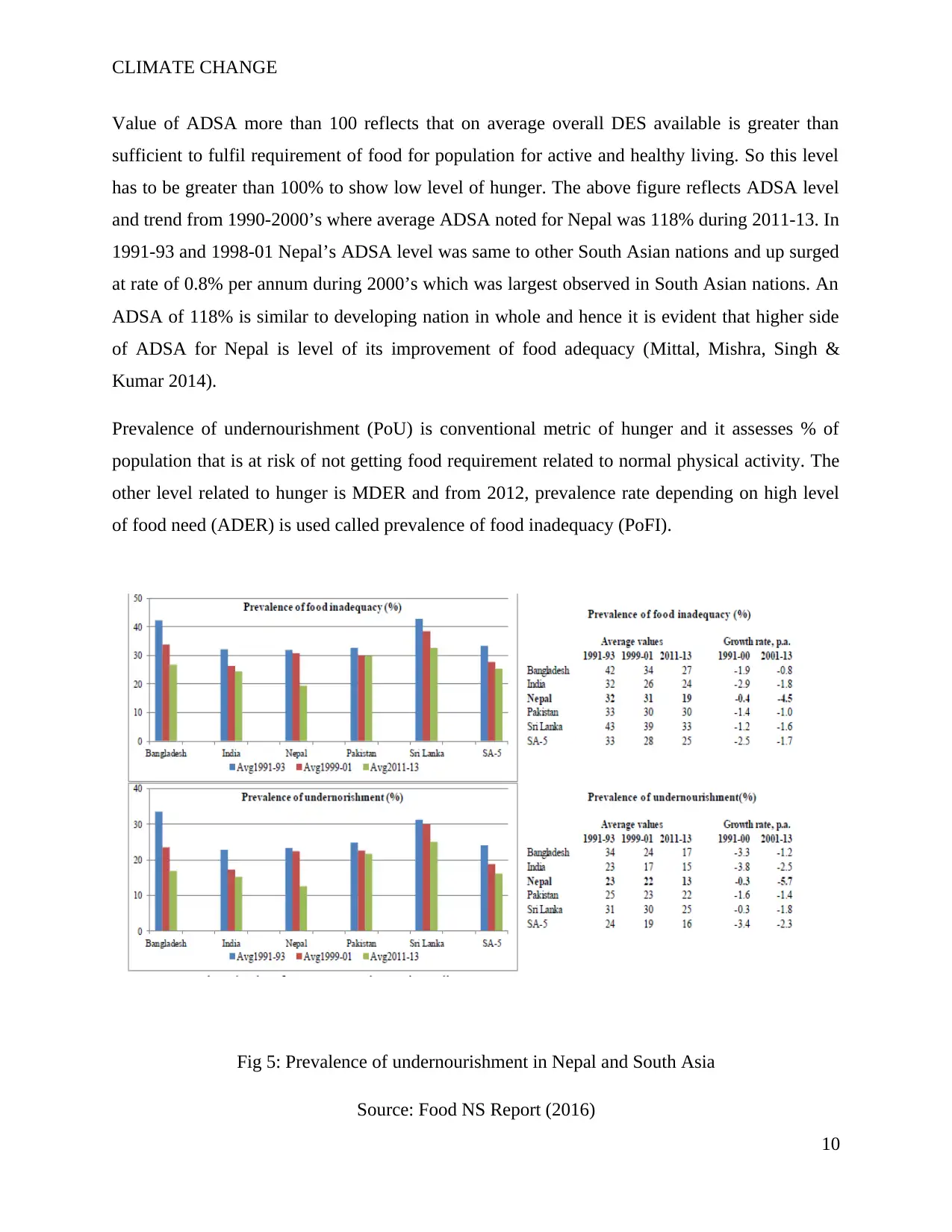

of outcome from agriculture and associated activities have been integrated at the sub sector or

major crop group level so as to evaluate the areas where Nepal is improving in context to

agriculture and to better identify those areas that have been declining rapidly in their

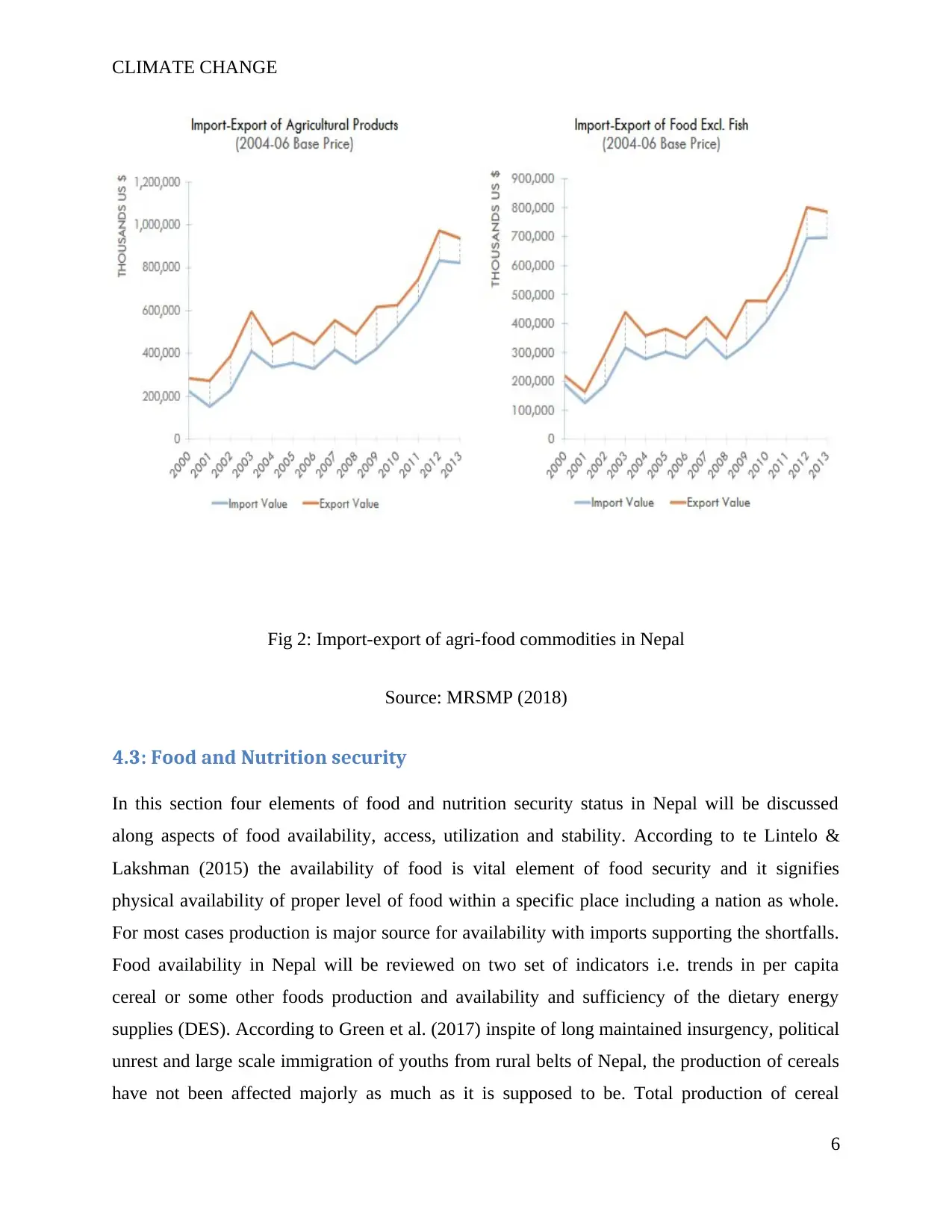

contributions. According to this status of agri-food products rate of total export between 2008-

2016, the vegetable produce is high value sector which consist of fruits, vegetable and spices,

followed food stuffs like cereals. The other sectors which are animal, livestock products and

other agri products fall at same level in context to contribution of value and share in total export

of agricultural products.

Fig 1: Status of agri-food product in Nepal

Source: MRSMP (2018)

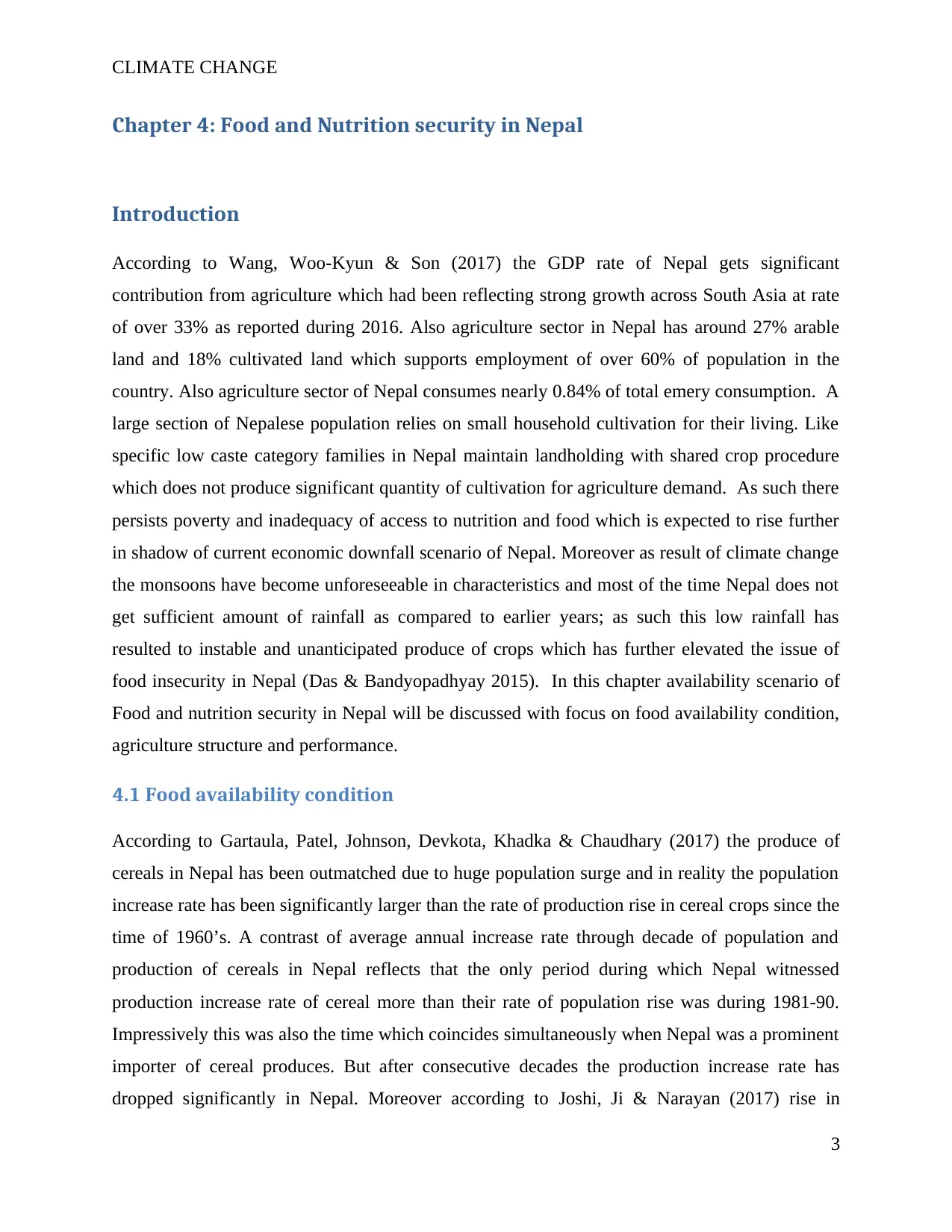

Also import value of agriculture products in year 2013 reached at 800,000 USD as compared to

export value which was around 90,000 USD during the same period, while in case of food

excluding fish the import value in 2013 was lower than export values which was 65,000 USD

and 80,000 respectively.

5

of outcome from agriculture and associated activities have been integrated at the sub sector or

major crop group level so as to evaluate the areas where Nepal is improving in context to

agriculture and to better identify those areas that have been declining rapidly in their

contributions. According to this status of agri-food products rate of total export between 2008-

2016, the vegetable produce is high value sector which consist of fruits, vegetable and spices,

followed food stuffs like cereals. The other sectors which are animal, livestock products and

other agri products fall at same level in context to contribution of value and share in total export

of agricultural products.

Fig 1: Status of agri-food product in Nepal

Source: MRSMP (2018)

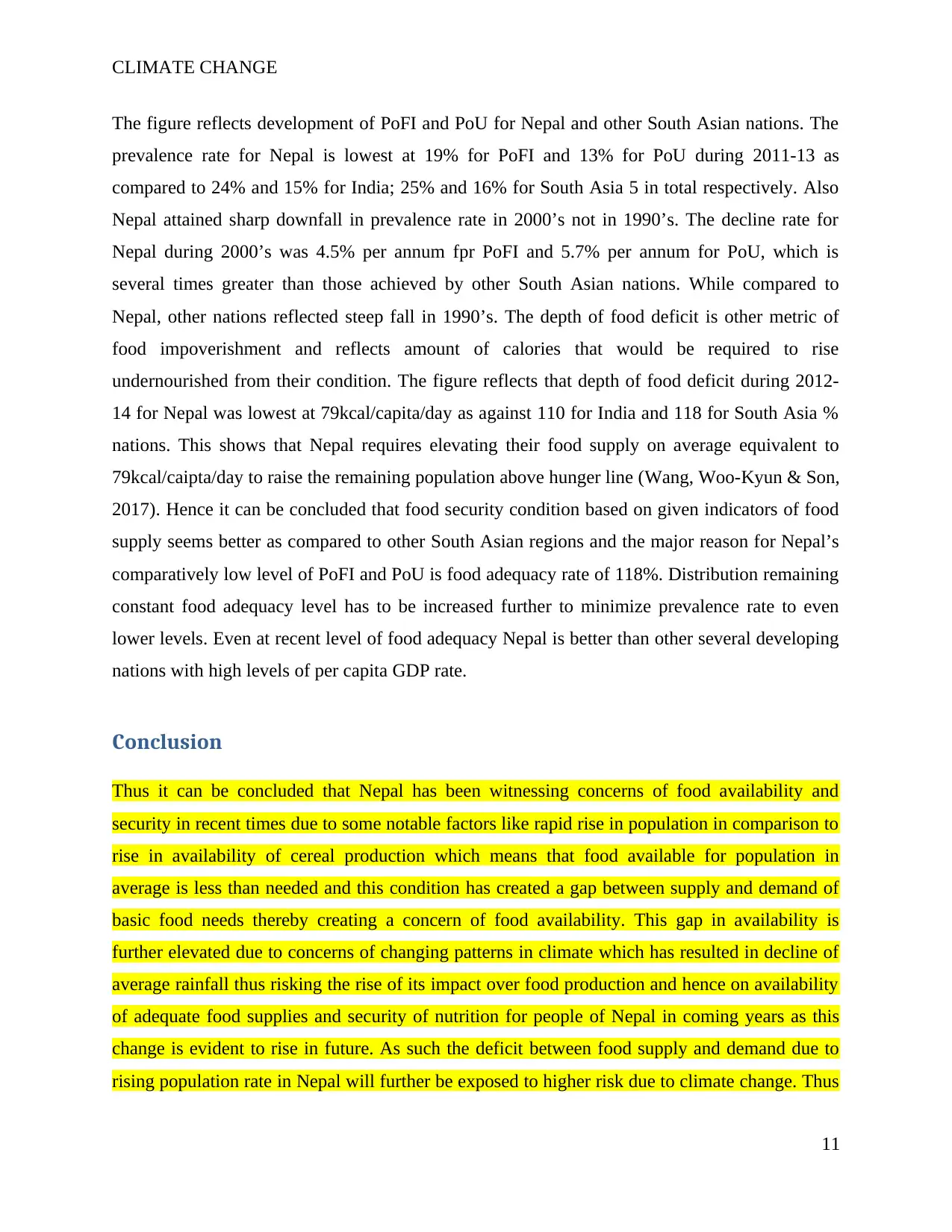

Also import value of agriculture products in year 2013 reached at 800,000 USD as compared to

export value which was around 90,000 USD during the same period, while in case of food

excluding fish the import value in 2013 was lower than export values which was 65,000 USD

and 80,000 respectively.

5

CLIMATE CHANGE

Fig 2: Import-export of agri-food commodities in Nepal

Source: MRSMP (2018)

4.3: Food and Nutrition security

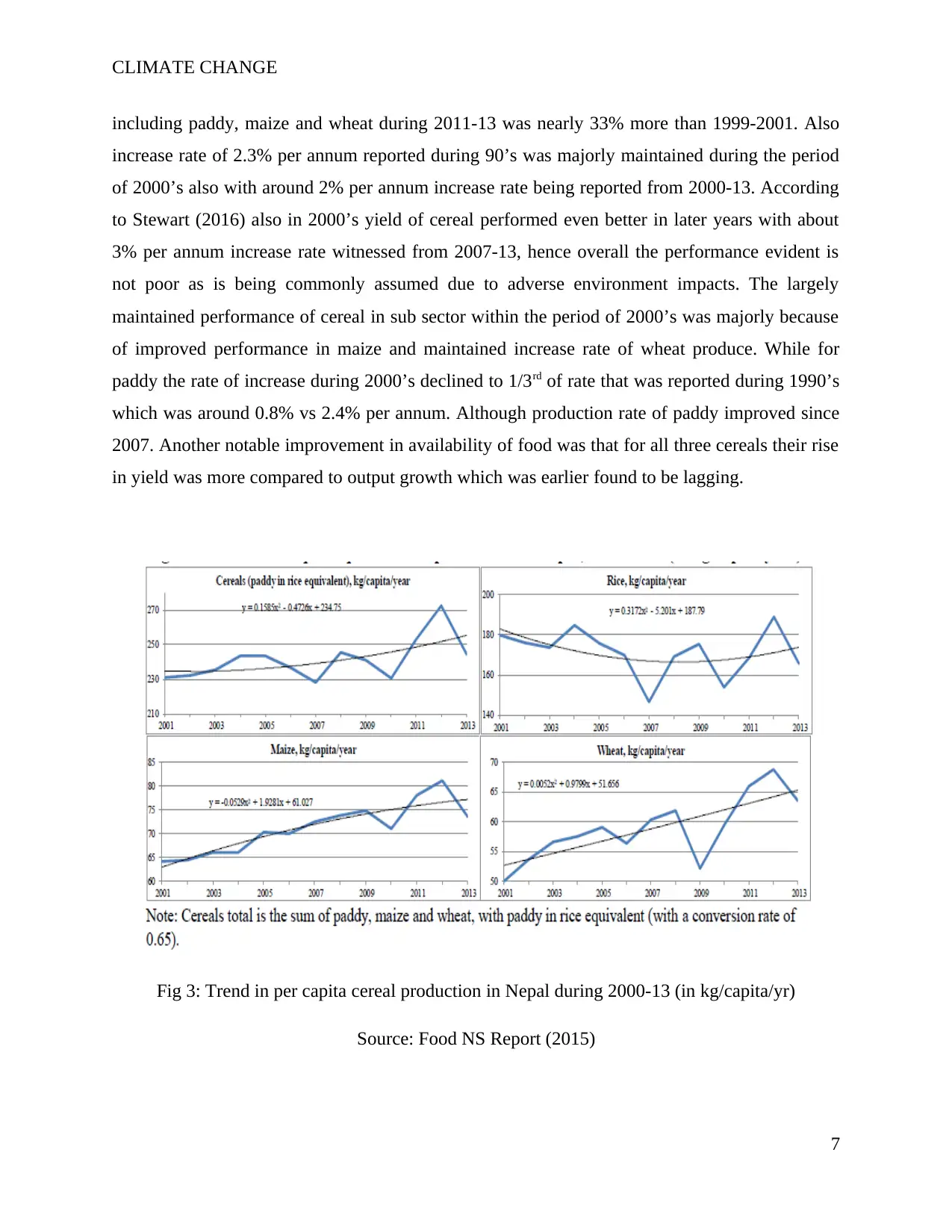

In this section four elements of food and nutrition security status in Nepal will be discussed

along aspects of food availability, access, utilization and stability. According to te Lintelo &

Lakshman (2015) the availability of food is vital element of food security and it signifies

physical availability of proper level of food within a specific place including a nation as whole.

For most cases production is major source for availability with imports supporting the shortfalls.

Food availability in Nepal will be reviewed on two set of indicators i.e. trends in per capita

cereal or some other foods production and availability and sufficiency of the dietary energy

supplies (DES). According to Green et al. (2017) inspite of long maintained insurgency, political

unrest and large scale immigration of youths from rural belts of Nepal, the production of cereals

have not been affected majorly as much as it is supposed to be. Total production of cereal

6

Fig 2: Import-export of agri-food commodities in Nepal

Source: MRSMP (2018)

4.3: Food and Nutrition security

In this section four elements of food and nutrition security status in Nepal will be discussed

along aspects of food availability, access, utilization and stability. According to te Lintelo &

Lakshman (2015) the availability of food is vital element of food security and it signifies

physical availability of proper level of food within a specific place including a nation as whole.

For most cases production is major source for availability with imports supporting the shortfalls.

Food availability in Nepal will be reviewed on two set of indicators i.e. trends in per capita

cereal or some other foods production and availability and sufficiency of the dietary energy

supplies (DES). According to Green et al. (2017) inspite of long maintained insurgency, political

unrest and large scale immigration of youths from rural belts of Nepal, the production of cereals

have not been affected majorly as much as it is supposed to be. Total production of cereal

6

CLIMATE CHANGE

including paddy, maize and wheat during 2011-13 was nearly 33% more than 1999-2001. Also

increase rate of 2.3% per annum reported during 90’s was majorly maintained during the period

of 2000’s also with around 2% per annum increase rate being reported from 2000-13. According

to Stewart (2016) also in 2000’s yield of cereal performed even better in later years with about

3% per annum increase rate witnessed from 2007-13, hence overall the performance evident is

not poor as is being commonly assumed due to adverse environment impacts. The largely

maintained performance of cereal in sub sector within the period of 2000’s was majorly because

of improved performance in maize and maintained increase rate of wheat produce. While for

paddy the rate of increase during 2000’s declined to 1/3rd of rate that was reported during 1990’s

which was around 0.8% vs 2.4% per annum. Although production rate of paddy improved since

2007. Another notable improvement in availability of food was that for all three cereals their rise

in yield was more compared to output growth which was earlier found to be lagging.

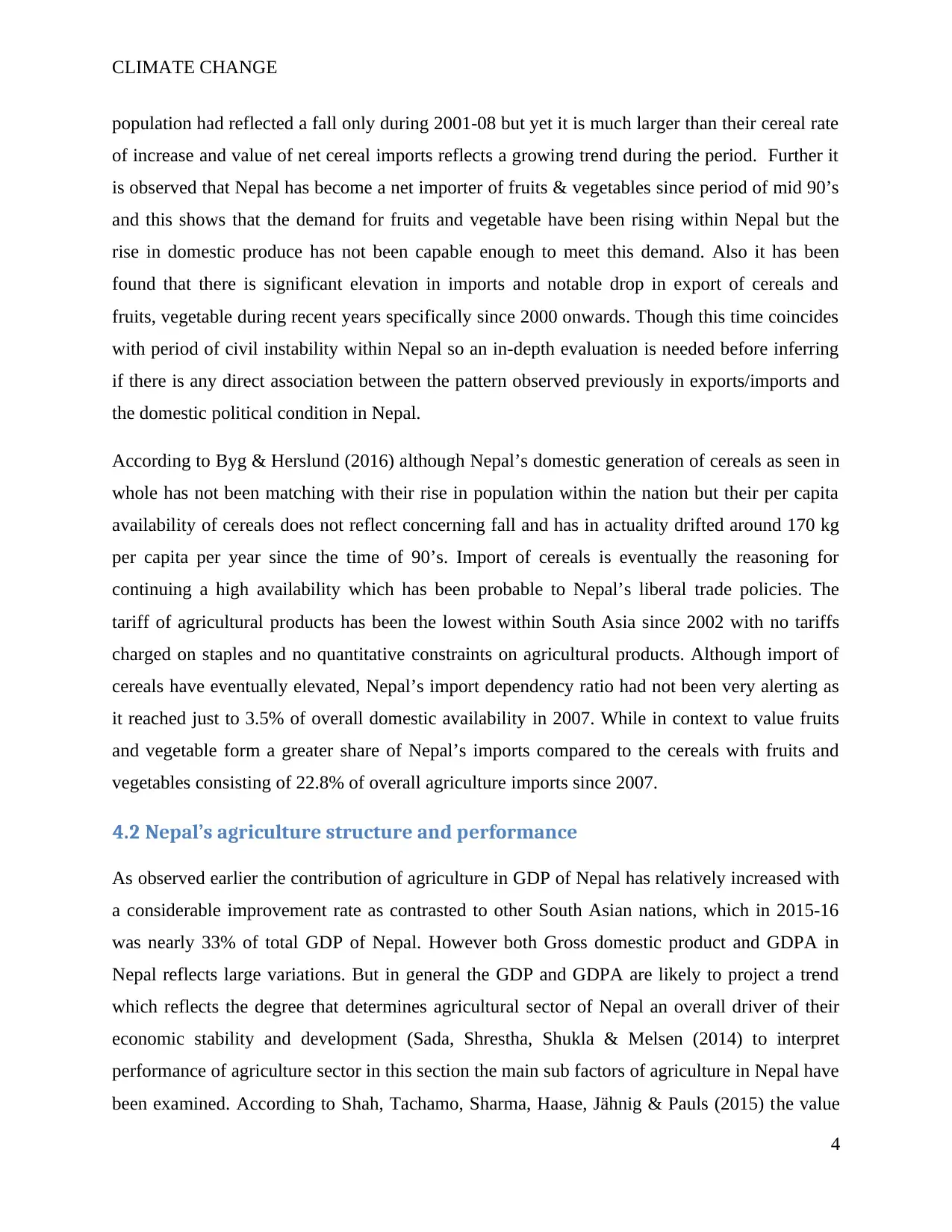

Fig 3: Trend in per capita cereal production in Nepal during 2000-13 (in kg/capita/yr)

Source: Food NS Report (2015)

7

including paddy, maize and wheat during 2011-13 was nearly 33% more than 1999-2001. Also

increase rate of 2.3% per annum reported during 90’s was majorly maintained during the period

of 2000’s also with around 2% per annum increase rate being reported from 2000-13. According

to Stewart (2016) also in 2000’s yield of cereal performed even better in later years with about

3% per annum increase rate witnessed from 2007-13, hence overall the performance evident is

not poor as is being commonly assumed due to adverse environment impacts. The largely

maintained performance of cereal in sub sector within the period of 2000’s was majorly because

of improved performance in maize and maintained increase rate of wheat produce. While for

paddy the rate of increase during 2000’s declined to 1/3rd of rate that was reported during 1990’s

which was around 0.8% vs 2.4% per annum. Although production rate of paddy improved since

2007. Another notable improvement in availability of food was that for all three cereals their rise

in yield was more compared to output growth which was earlier found to be lagging.

Fig 3: Trend in per capita cereal production in Nepal during 2000-13 (in kg/capita/yr)

Source: Food NS Report (2015)

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CLIMATE CHANGE

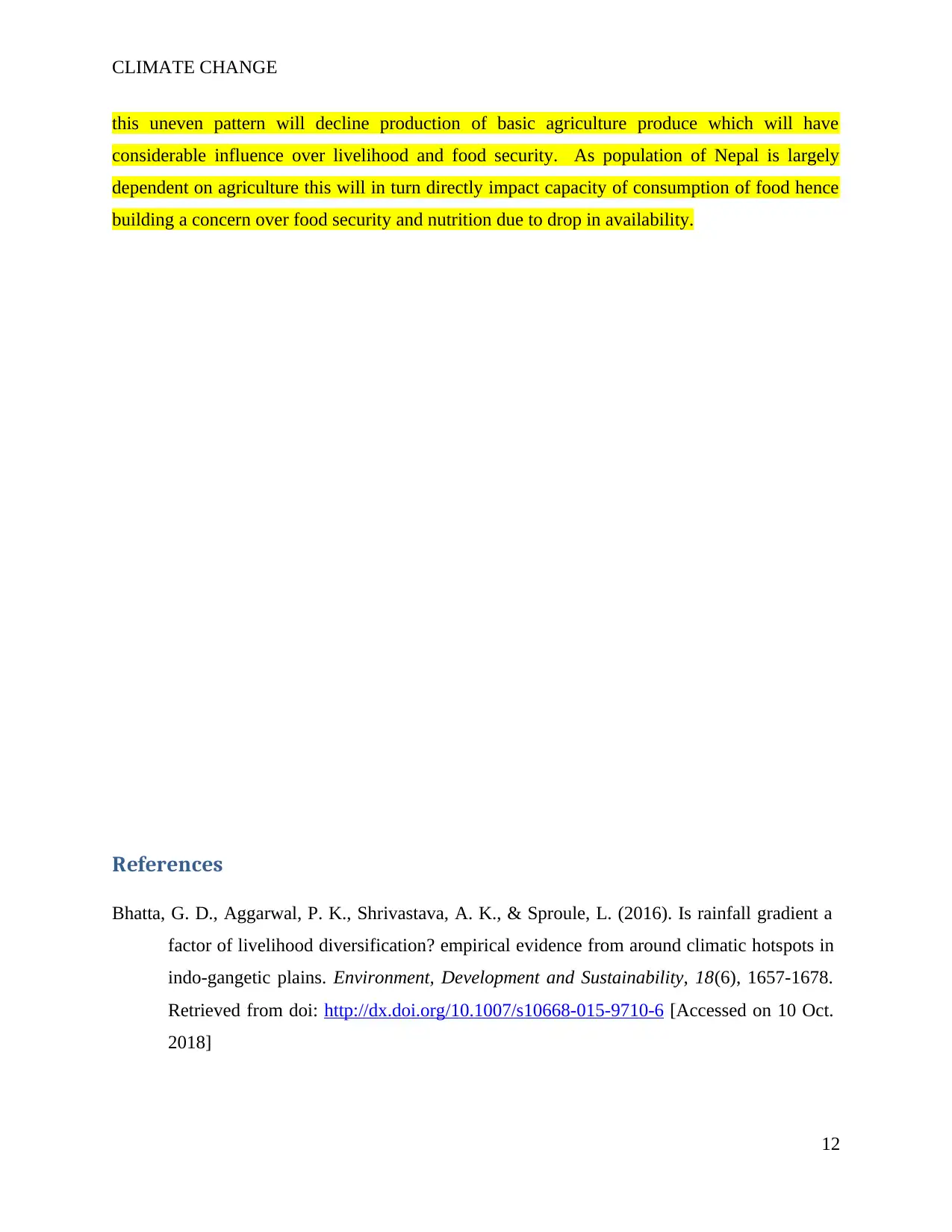

The figure reflects overall pattern in production of cereal on per capita basis from 2000-13 which

was positive for maize, wheat and cereals in total while was negative for paddy till 2008 after

which the pattern improved positively and fairly reporting to 1.9% per annum between 2007-13.

Also output/person for paddy was 174 kg during 2011-13 that was lower than during 2001-03

(177kg). Also other reflections from the figure is that instability of production in pattern has

been likely rising during recent years and examination reflects that overall food supply which

means counting all foods consumed in Nepal has been developing. The table below shows

percent change and pattern in cereal production in Nepal during 2000-13. This was mainly due to

rising imports but their share in total food supply is small and hence most of acknowledgement

for development in aggregate food condition in Nepal goes to domestic production.

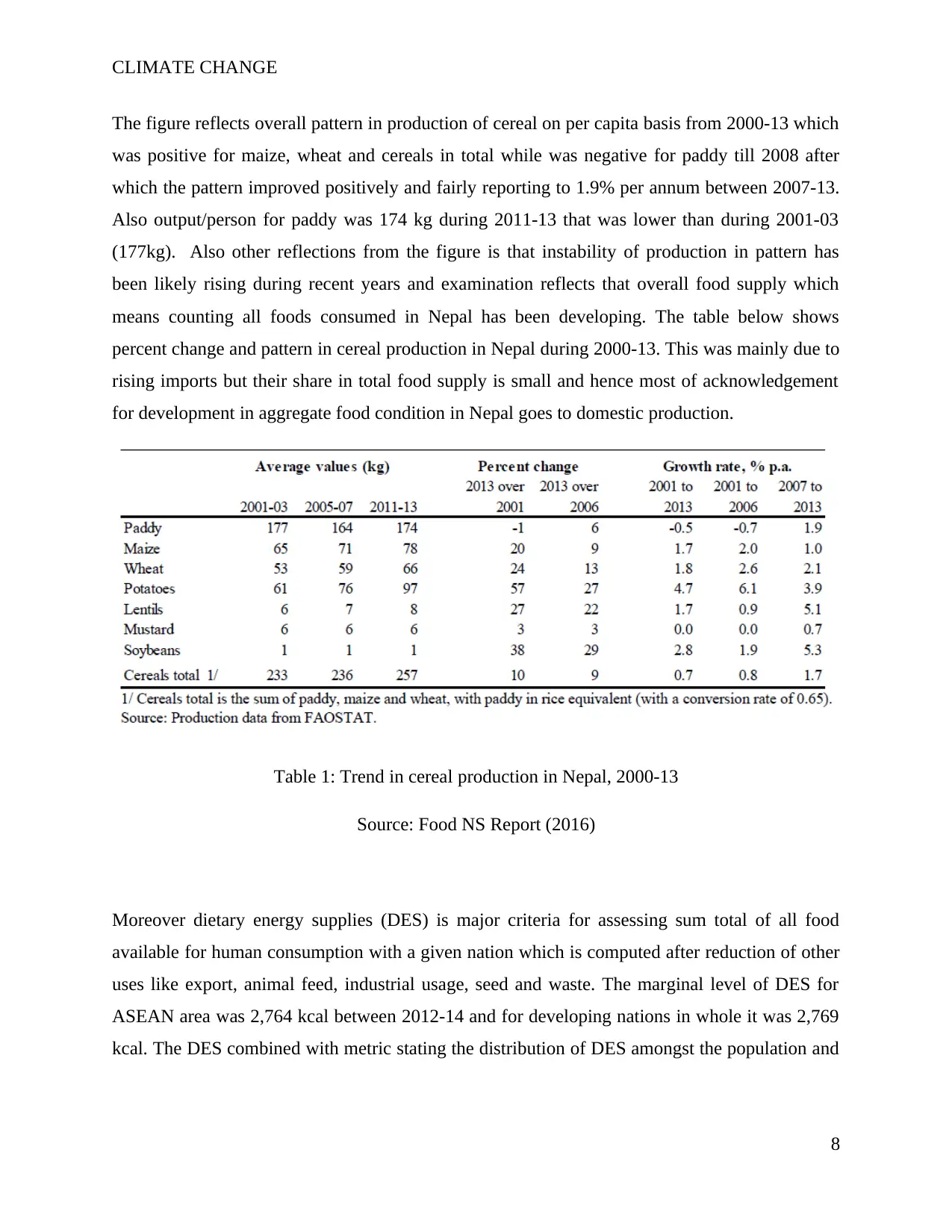

Table 1: Trend in cereal production in Nepal, 2000-13

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

Moreover dietary energy supplies (DES) is major criteria for assessing sum total of all food

available for human consumption with a given nation which is computed after reduction of other

uses like export, animal feed, industrial usage, seed and waste. The marginal level of DES for

ASEAN area was 2,764 kcal between 2012-14 and for developing nations in whole it was 2,769

kcal. The DES combined with metric stating the distribution of DES amongst the population and

8

The figure reflects overall pattern in production of cereal on per capita basis from 2000-13 which

was positive for maize, wheat and cereals in total while was negative for paddy till 2008 after

which the pattern improved positively and fairly reporting to 1.9% per annum between 2007-13.

Also output/person for paddy was 174 kg during 2011-13 that was lower than during 2001-03

(177kg). Also other reflections from the figure is that instability of production in pattern has

been likely rising during recent years and examination reflects that overall food supply which

means counting all foods consumed in Nepal has been developing. The table below shows

percent change and pattern in cereal production in Nepal during 2000-13. This was mainly due to

rising imports but their share in total food supply is small and hence most of acknowledgement

for development in aggregate food condition in Nepal goes to domestic production.

Table 1: Trend in cereal production in Nepal, 2000-13

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

Moreover dietary energy supplies (DES) is major criteria for assessing sum total of all food

available for human consumption with a given nation which is computed after reduction of other

uses like export, animal feed, industrial usage, seed and waste. The marginal level of DES for

ASEAN area was 2,764 kcal between 2012-14 and for developing nations in whole it was 2,769

kcal. The DES combined with metric stating the distribution of DES amongst the population and

8

CLIMATE CHANGE

normative minimum need demonstrates situation of undernourishment or food insufficiency in a

nation.

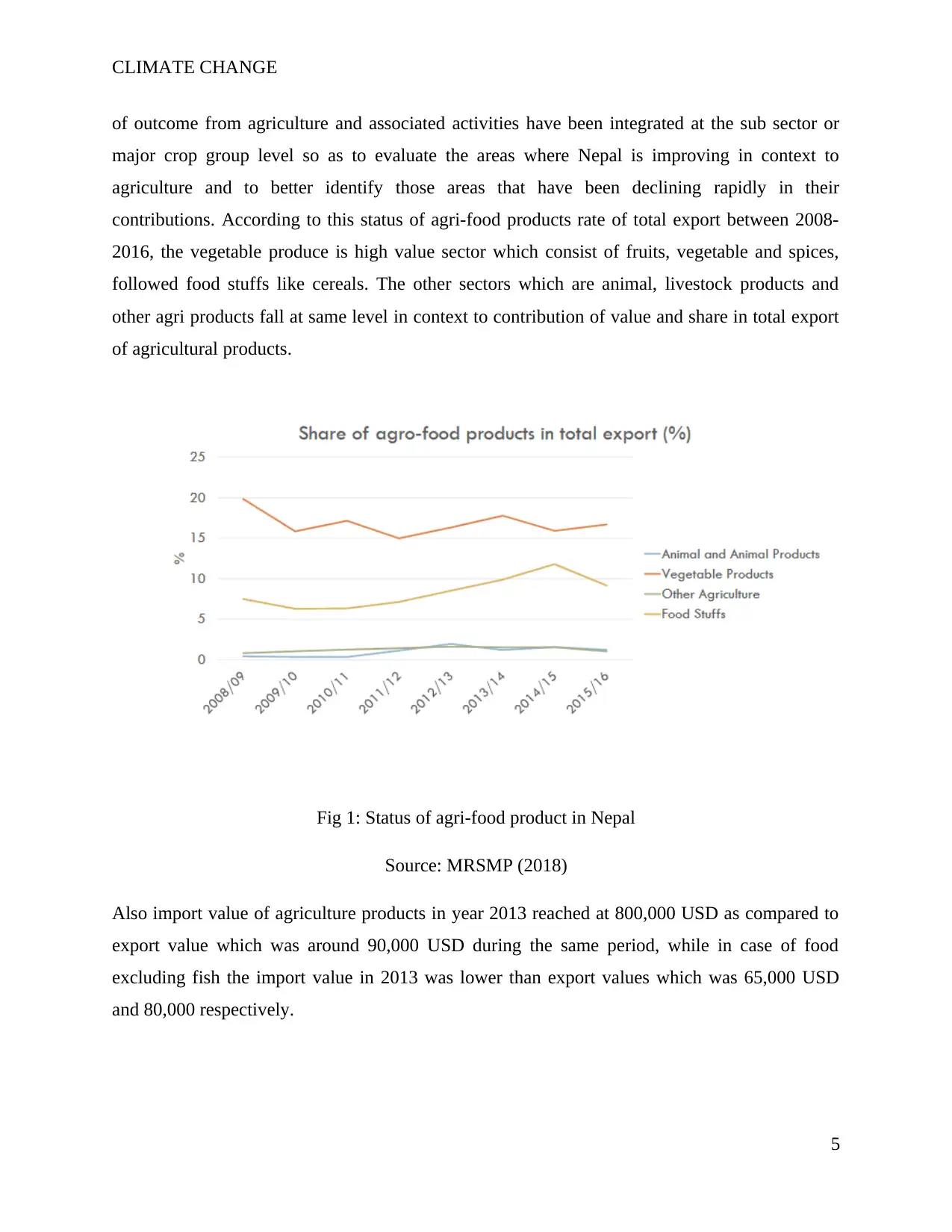

Fig 4: Trend in DES and their sufficiency level for Nepal and other South Asian regions

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

The above figure reflects level and rate of rise of DES for Nepal and lower figure shows

adequacy rate. Also data for other South Asian regions is given for contrast in status of Nepal.

The average level of DES in Nepal was generally lower compared to South Asian nations

between 1990-2001 and 1999-2001. But between 2001-13 DES rate in Nepal improved and was

fastest amongst other comparative regions which was reported as 2.544kcal during 2011-13.

Moreover according to Bhatta, Aggarwal, Shrivastava & Sproule (2016) DES level requires to be

examined against requirement indicators for evaluating sufficiency. These two requirements are

Average Dietary Supply Adequacy (ADSA) which reflects DES as % of Average Dietary Energy

Requirement (ADER). ADER encompasses food needs related with normal physical activity.

The other requirement metric for DES in context of food needs is Minimum Dietary Energy

Requirement (MDER) which reflects amount of energy required for light activity. MDER is one

of the metrics that is applied for evaluating traditional existence of undernourishment in a region.

9

normative minimum need demonstrates situation of undernourishment or food insufficiency in a

nation.

Fig 4: Trend in DES and their sufficiency level for Nepal and other South Asian regions

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

The above figure reflects level and rate of rise of DES for Nepal and lower figure shows

adequacy rate. Also data for other South Asian regions is given for contrast in status of Nepal.

The average level of DES in Nepal was generally lower compared to South Asian nations

between 1990-2001 and 1999-2001. But between 2001-13 DES rate in Nepal improved and was

fastest amongst other comparative regions which was reported as 2.544kcal during 2011-13.

Moreover according to Bhatta, Aggarwal, Shrivastava & Sproule (2016) DES level requires to be

examined against requirement indicators for evaluating sufficiency. These two requirements are

Average Dietary Supply Adequacy (ADSA) which reflects DES as % of Average Dietary Energy

Requirement (ADER). ADER encompasses food needs related with normal physical activity.

The other requirement metric for DES in context of food needs is Minimum Dietary Energy

Requirement (MDER) which reflects amount of energy required for light activity. MDER is one

of the metrics that is applied for evaluating traditional existence of undernourishment in a region.

9

CLIMATE CHANGE

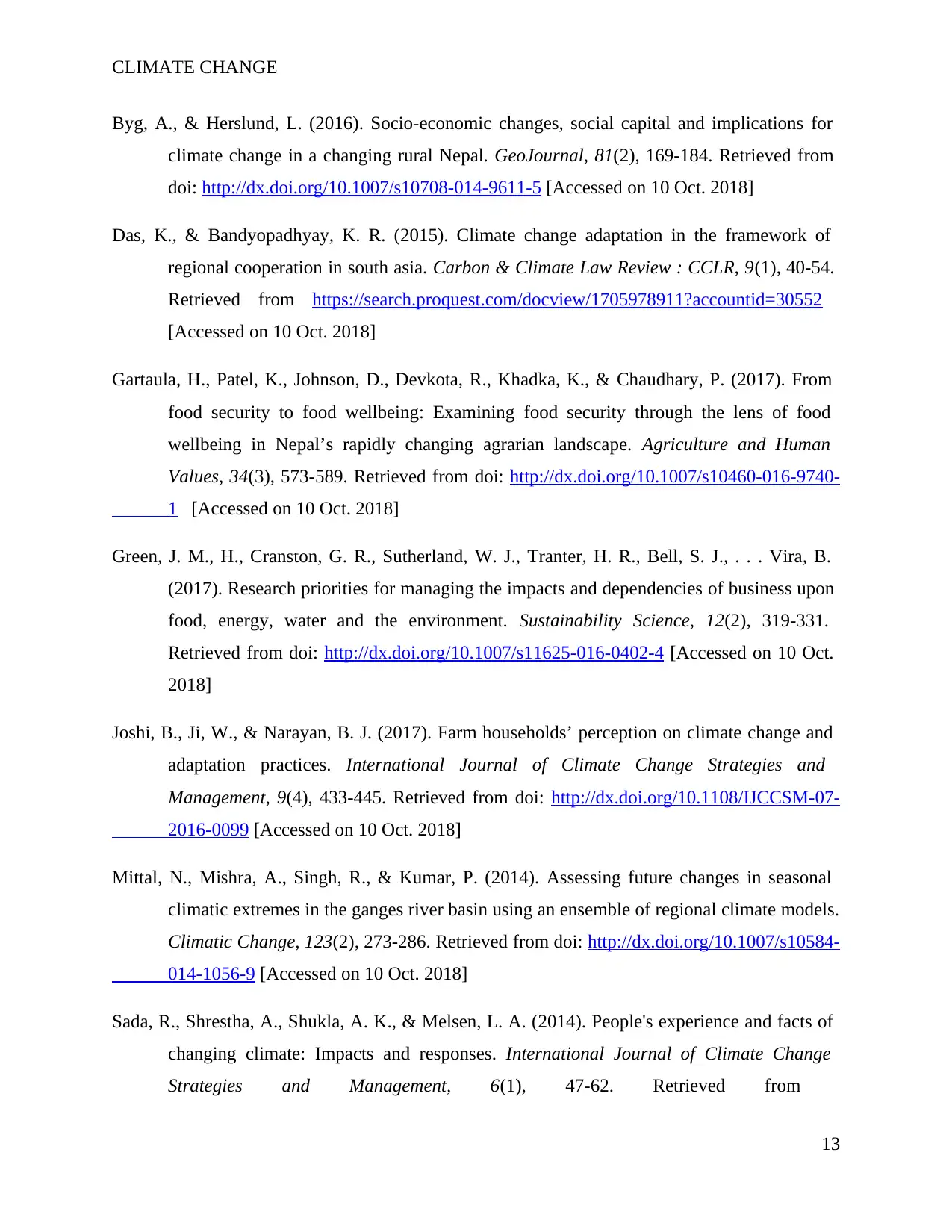

Value of ADSA more than 100 reflects that on average overall DES available is greater than

sufficient to fulfil requirement of food for population for active and healthy living. So this level

has to be greater than 100% to show low level of hunger. The above figure reflects ADSA level

and trend from 1990-2000’s where average ADSA noted for Nepal was 118% during 2011-13. In

1991-93 and 1998-01 Nepal’s ADSA level was same to other South Asian nations and up surged

at rate of 0.8% per annum during 2000’s which was largest observed in South Asian nations. An

ADSA of 118% is similar to developing nation in whole and hence it is evident that higher side

of ADSA for Nepal is level of its improvement of food adequacy (Mittal, Mishra, Singh &

Kumar 2014).

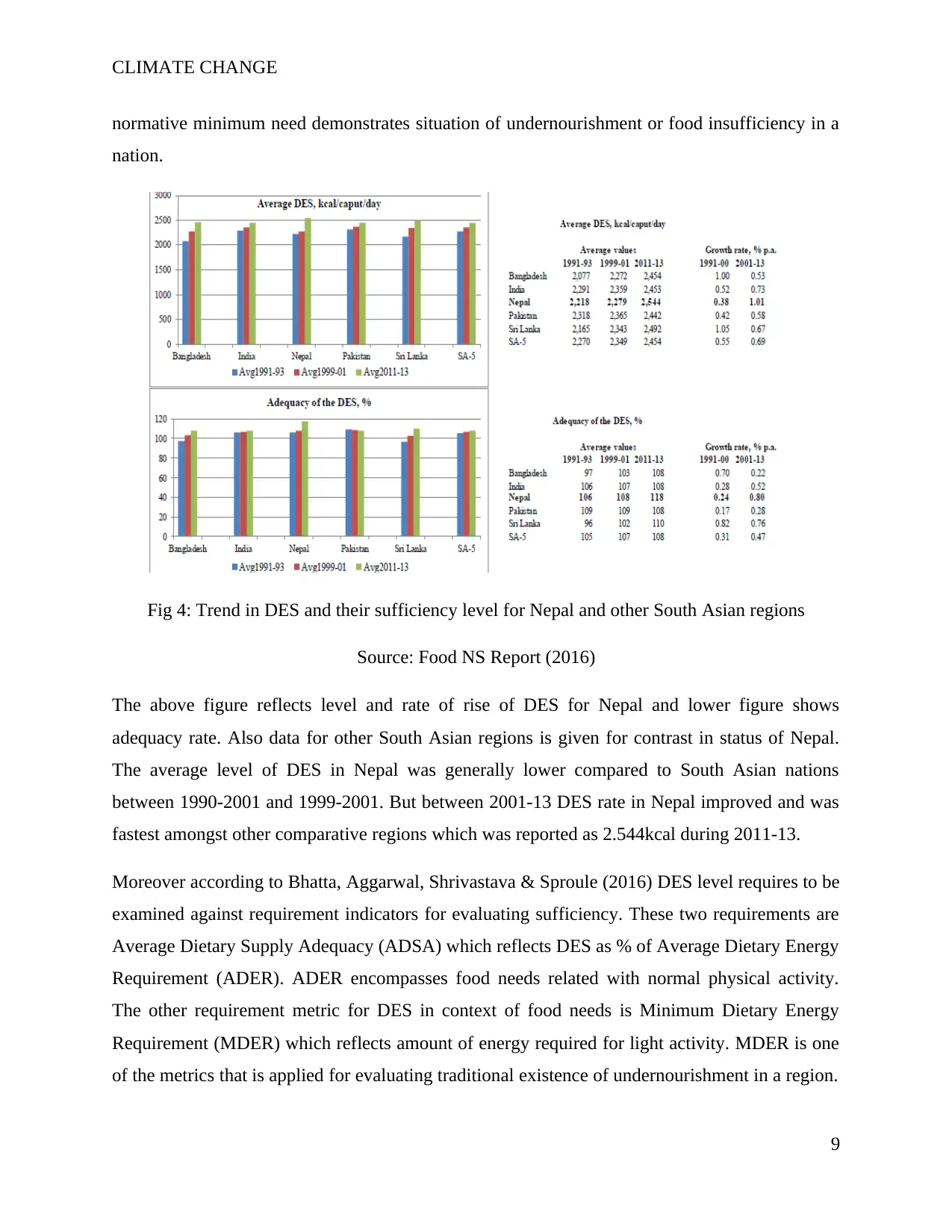

Prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) is conventional metric of hunger and it assesses % of

population that is at risk of not getting food requirement related to normal physical activity. The

other level related to hunger is MDER and from 2012, prevalence rate depending on high level

of food need (ADER) is used called prevalence of food inadequacy (PoFI).

Fig 5: Prevalence of undernourishment in Nepal and South Asia

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

10

Value of ADSA more than 100 reflects that on average overall DES available is greater than

sufficient to fulfil requirement of food for population for active and healthy living. So this level

has to be greater than 100% to show low level of hunger. The above figure reflects ADSA level

and trend from 1990-2000’s where average ADSA noted for Nepal was 118% during 2011-13. In

1991-93 and 1998-01 Nepal’s ADSA level was same to other South Asian nations and up surged

at rate of 0.8% per annum during 2000’s which was largest observed in South Asian nations. An

ADSA of 118% is similar to developing nation in whole and hence it is evident that higher side

of ADSA for Nepal is level of its improvement of food adequacy (Mittal, Mishra, Singh &

Kumar 2014).

Prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) is conventional metric of hunger and it assesses % of

population that is at risk of not getting food requirement related to normal physical activity. The

other level related to hunger is MDER and from 2012, prevalence rate depending on high level

of food need (ADER) is used called prevalence of food inadequacy (PoFI).

Fig 5: Prevalence of undernourishment in Nepal and South Asia

Source: Food NS Report (2016)

10

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CLIMATE CHANGE

The figure reflects development of PoFI and PoU for Nepal and other South Asian nations. The

prevalence rate for Nepal is lowest at 19% for PoFI and 13% for PoU during 2011-13 as

compared to 24% and 15% for India; 25% and 16% for South Asia 5 in total respectively. Also

Nepal attained sharp downfall in prevalence rate in 2000’s not in 1990’s. The decline rate for

Nepal during 2000’s was 4.5% per annum fpr PoFI and 5.7% per annum for PoU, which is

several times greater than those achieved by other South Asian nations. While compared to

Nepal, other nations reflected steep fall in 1990’s. The depth of food deficit is other metric of

food impoverishment and reflects amount of calories that would be required to rise

undernourished from their condition. The figure reflects that depth of food deficit during 2012-

14 for Nepal was lowest at 79kcal/capita/day as against 110 for India and 118 for South Asia %

nations. This shows that Nepal requires elevating their food supply on average equivalent to

79kcal/caipta/day to raise the remaining population above hunger line (Wang, Woo-Kyun & Son,

2017). Hence it can be concluded that food security condition based on given indicators of food

supply seems better as compared to other South Asian regions and the major reason for Nepal’s

comparatively low level of PoFI and PoU is food adequacy rate of 118%. Distribution remaining

constant food adequacy level has to be increased further to minimize prevalence rate to even

lower levels. Even at recent level of food adequacy Nepal is better than other several developing

nations with high levels of per capita GDP rate.

Conclusion

Thus it can be concluded that Nepal has been witnessing concerns of food availability and

security in recent times due to some notable factors like rapid rise in population in comparison to

rise in availability of cereal production which means that food available for population in

average is less than needed and this condition has created a gap between supply and demand of

basic food needs thereby creating a concern of food availability. This gap in availability is

further elevated due to concerns of changing patterns in climate which has resulted in decline of

average rainfall thus risking the rise of its impact over food production and hence on availability

of adequate food supplies and security of nutrition for people of Nepal in coming years as this

change is evident to rise in future. As such the deficit between food supply and demand due to

rising population rate in Nepal will further be exposed to higher risk due to climate change. Thus

11

The figure reflects development of PoFI and PoU for Nepal and other South Asian nations. The

prevalence rate for Nepal is lowest at 19% for PoFI and 13% for PoU during 2011-13 as

compared to 24% and 15% for India; 25% and 16% for South Asia 5 in total respectively. Also

Nepal attained sharp downfall in prevalence rate in 2000’s not in 1990’s. The decline rate for

Nepal during 2000’s was 4.5% per annum fpr PoFI and 5.7% per annum for PoU, which is

several times greater than those achieved by other South Asian nations. While compared to

Nepal, other nations reflected steep fall in 1990’s. The depth of food deficit is other metric of

food impoverishment and reflects amount of calories that would be required to rise

undernourished from their condition. The figure reflects that depth of food deficit during 2012-

14 for Nepal was lowest at 79kcal/capita/day as against 110 for India and 118 for South Asia %

nations. This shows that Nepal requires elevating their food supply on average equivalent to

79kcal/caipta/day to raise the remaining population above hunger line (Wang, Woo-Kyun & Son,

2017). Hence it can be concluded that food security condition based on given indicators of food

supply seems better as compared to other South Asian regions and the major reason for Nepal’s

comparatively low level of PoFI and PoU is food adequacy rate of 118%. Distribution remaining

constant food adequacy level has to be increased further to minimize prevalence rate to even

lower levels. Even at recent level of food adequacy Nepal is better than other several developing

nations with high levels of per capita GDP rate.

Conclusion

Thus it can be concluded that Nepal has been witnessing concerns of food availability and

security in recent times due to some notable factors like rapid rise in population in comparison to

rise in availability of cereal production which means that food available for population in

average is less than needed and this condition has created a gap between supply and demand of

basic food needs thereby creating a concern of food availability. This gap in availability is

further elevated due to concerns of changing patterns in climate which has resulted in decline of

average rainfall thus risking the rise of its impact over food production and hence on availability

of adequate food supplies and security of nutrition for people of Nepal in coming years as this

change is evident to rise in future. As such the deficit between food supply and demand due to

rising population rate in Nepal will further be exposed to higher risk due to climate change. Thus

11

CLIMATE CHANGE

this uneven pattern will decline production of basic agriculture produce which will have

considerable influence over livelihood and food security. As population of Nepal is largely

dependent on agriculture this will in turn directly impact capacity of consumption of food hence

building a concern over food security and nutrition due to drop in availability.

References

Bhatta, G. D., Aggarwal, P. K., Shrivastava, A. K., & Sproule, L. (2016). Is rainfall gradient a

factor of livelihood diversification? empirical evidence from around climatic hotspots in

indo-gangetic plains. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(6), 1657-1678.

Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9710-6 [Accessed on 10 Oct.

2018]

12

this uneven pattern will decline production of basic agriculture produce which will have

considerable influence over livelihood and food security. As population of Nepal is largely

dependent on agriculture this will in turn directly impact capacity of consumption of food hence

building a concern over food security and nutrition due to drop in availability.

References

Bhatta, G. D., Aggarwal, P. K., Shrivastava, A. K., & Sproule, L. (2016). Is rainfall gradient a

factor of livelihood diversification? empirical evidence from around climatic hotspots in

indo-gangetic plains. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(6), 1657-1678.

Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9710-6 [Accessed on 10 Oct.

2018]

12

CLIMATE CHANGE

Byg, A., & Herslund, L. (2016). Socio-economic changes, social capital and implications for

climate change in a changing rural Nepal. GeoJournal, 81(2), 169-184. Retrieved from

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9611-5 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Das, K., & Bandyopadhyay, K. R. (2015). Climate change adaptation in the framework of

regional cooperation in south asia. Carbon & Climate Law Review : CCLR, 9(1), 40-54.

Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1705978911?accountid=30552

[Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Gartaula, H., Patel, K., Johnson, D., Devkota, R., Khadka, K., & Chaudhary, P. (2017). From

food security to food wellbeing: Examining food security through the lens of food

wellbeing in Nepal’s rapidly changing agrarian landscape. Agriculture and Human

Values, 34(3), 573-589. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9740-

1 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Green, J. M., H., Cranston, G. R., Sutherland, W. J., Tranter, H. R., Bell, S. J., . . . Vira, B.

(2017). Research priorities for managing the impacts and dependencies of business upon

food, energy, water and the environment. Sustainability Science, 12(2), 319-331.

Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0402-4 [Accessed on 10 Oct.

2018]

Joshi, B., Ji, W., & Narayan, B. J. (2017). Farm households’ perception on climate change and

adaptation practices. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and

Management, 9(4), 433-445. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-07-

2016-0099 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Mittal, N., Mishra, A., Singh, R., & Kumar, P. (2014). Assessing future changes in seasonal

climatic extremes in the ganges river basin using an ensemble of regional climate models.

Climatic Change, 123(2), 273-286. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-

014-1056-9 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Sada, R., Shrestha, A., Shukla, A. K., & Melsen, L. A. (2014). People's experience and facts of

changing climate: Impacts and responses. International Journal of Climate Change

Strategies and Management, 6(1), 47-62. Retrieved from

13

Byg, A., & Herslund, L. (2016). Socio-economic changes, social capital and implications for

climate change in a changing rural Nepal. GeoJournal, 81(2), 169-184. Retrieved from

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9611-5 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Das, K., & Bandyopadhyay, K. R. (2015). Climate change adaptation in the framework of

regional cooperation in south asia. Carbon & Climate Law Review : CCLR, 9(1), 40-54.

Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1705978911?accountid=30552

[Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Gartaula, H., Patel, K., Johnson, D., Devkota, R., Khadka, K., & Chaudhary, P. (2017). From

food security to food wellbeing: Examining food security through the lens of food

wellbeing in Nepal’s rapidly changing agrarian landscape. Agriculture and Human

Values, 34(3), 573-589. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9740-

1 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Green, J. M., H., Cranston, G. R., Sutherland, W. J., Tranter, H. R., Bell, S. J., . . . Vira, B.

(2017). Research priorities for managing the impacts and dependencies of business upon

food, energy, water and the environment. Sustainability Science, 12(2), 319-331.

Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0402-4 [Accessed on 10 Oct.

2018]

Joshi, B., Ji, W., & Narayan, B. J. (2017). Farm households’ perception on climate change and

adaptation practices. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and

Management, 9(4), 433-445. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-07-

2016-0099 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Mittal, N., Mishra, A., Singh, R., & Kumar, P. (2014). Assessing future changes in seasonal

climatic extremes in the ganges river basin using an ensemble of regional climate models.

Climatic Change, 123(2), 273-286. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-

014-1056-9 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Sada, R., Shrestha, A., Shukla, A. K., & Melsen, L. A. (2014). People's experience and facts of

changing climate: Impacts and responses. International Journal of Climate Change

Strategies and Management, 6(1), 47-62. Retrieved from

13

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CLIMATE CHANGE

https://search.proquest.com/docview/1493448243?accountid=30552 [Accessed on 10

Oct. 2018]

Shah, R. D., Tachamo, Sharma, S., Haase, P., Jähnig, S.,C., & Pauls, S. U. (2015). The climate

sensitive zone along an altitudinal gradient in central himalayan rivers: A useful concept

to monitor climate change impacts in mountain regions. Climatic Change, 132(2), 265-

278. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1417-z [Accessed on 10

Oct. 2018]

Stewart, F. (2016). Changing perspectives on inequality and development. Studies in

Comparative International Development, 51(1), 60-80. Retrieved from doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12116-016-9222-x [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

te Lintelo, D.,J.H., & Lakshman, R. W. D. (2015). Equate and conflate: Political commitment to

hunger and under nutrition reduction in five high-burden countries. World Development,

76, 280. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.07.013 [Accessed

on 10 Oct. 2018]

Wang, S. W., Woo-Kyun, L., & Son, Y. (2017). An assessment of climate change impacts and

adaptation in south asian agriculture. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies

and Management, 9(4), 517-534. Retrieved from: doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-05-2016-0069 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Figures & Tables

Fig 1 Pandit., J (2018). Export Potential of Agriculture and Food Products of Nepal. Retrieved

from: http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf [Accessed on 31 Oct.

2018]

14

https://search.proquest.com/docview/1493448243?accountid=30552 [Accessed on 10

Oct. 2018]

Shah, R. D., Tachamo, Sharma, S., Haase, P., Jähnig, S.,C., & Pauls, S. U. (2015). The climate

sensitive zone along an altitudinal gradient in central himalayan rivers: A useful concept

to monitor climate change impacts in mountain regions. Climatic Change, 132(2), 265-

278. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1417-z [Accessed on 10

Oct. 2018]

Stewart, F. (2016). Changing perspectives on inequality and development. Studies in

Comparative International Development, 51(1), 60-80. Retrieved from doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12116-016-9222-x [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

te Lintelo, D.,J.H., & Lakshman, R. W. D. (2015). Equate and conflate: Political commitment to

hunger and under nutrition reduction in five high-burden countries. World Development,

76, 280. Retrieved from doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.07.013 [Accessed

on 10 Oct. 2018]

Wang, S. W., Woo-Kyun, L., & Son, Y. (2017). An assessment of climate change impacts and

adaptation in south asian agriculture. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies

and Management, 9(4), 517-534. Retrieved from: doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-05-2016-0069 [Accessed on 10 Oct. 2018]

Figures & Tables

Fig 1 Pandit., J (2018). Export Potential of Agriculture and Food Products of Nepal. Retrieved

from: http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf [Accessed on 31 Oct.

2018]

14

CLIMATE CHANGE

Fig 2 Pandit., J (2018). Export Potential of Agriculture and Food Products of Nepal. Retrieved

from: http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf [Accessed on 31 Oct.

2018]

Fig 3 Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Table 1 Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Fig 4: Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Fig 5: Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

15

Fig 2 Pandit., J (2018). Export Potential of Agriculture and Food Products of Nepal. Retrieved

from: http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf [Accessed on 31 Oct.

2018]

Fig 3 Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Table 1 Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Fig 4: Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

Fig 5: Ministry of Agricultural Development and Central Bureau of Statistics (2016) Food and

Nutrition security in Nepal: A Status report. Retrieved from:

http://moad.gov.np/public/uploads/201721855-final%20Food%20NS%202015.pdf

[Accessed on 31 Oct. 2018]

15

CLIMATE CHANGE

http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/apcas26/presentations/APCAS-16-

6.4.4_-_Nepal_-_Food_Security.pdf

16

http://www.ips.lk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Nepal.pdf

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/apcas26/presentations/APCAS-16-

6.4.4_-_Nepal_-_Food_Security.pdf

16

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CLIMATE CHANGE

17

17

1 out of 17

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.