Cornell Study: Supportive Work Practices and Customer Service Impact

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/24

|15

|11220

|54

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a study from Cornell University's School of Hotel Administration, investigates the impact of supportive work practices on customer-contact employees within the hospitality industry. The research examines the relationship between employees' perceptions of service climate and their motivation, job performance, and intentions to leave. The study defines supportive service climate as encompassing HR support, management support, and job support, all of which contribute to employees' ability to provide quality customer service. The findings highlight the importance of fostering a supportive work environment through HR policies, managerial behaviors, and job design to enhance employee engagement, performance, and retention. The research emphasizes the significance of service climate perceptions and provides insights for effectively managing customer-contact staff and improving service quality. The study also explores the mediating role of motivation in the relationship between service climate and job performance, addressing the issue of high turnover in the hospitality sector.

Cornell University School of Hotel Administration

The Scholarly Commons

Articles and Chapters School of Hotel Administration Collection

5-2013

Got Support? The Impact of Supportive Wo

Practices on the Perceptions, Motivation, an

Behavior of Customer-Contact Employees

John W. Michel

Loyola University

Michael J. Kavanagh

State University of New York, Albany

J. Bruce Tracey

Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, jbt6@cornell.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles

Part of the Performance Management Commons

This Article or Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hotel Administration Collection at The Scholarly Commo

been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of The Scholarly Commons. For more information, plea

hotellibrary@cornell.edu.

Recommended Citation

Michel, J. W., Kavanagh, M. J., & Tracey, J. B. (2013). Got support? The impact of supportive work practices on the perceptio

motivation, and behavior of customer-contact employees. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(2), 161-173. doi:10.1177/

1938965512454595

The Scholarly Commons

Articles and Chapters School of Hotel Administration Collection

5-2013

Got Support? The Impact of Supportive Wo

Practices on the Perceptions, Motivation, an

Behavior of Customer-Contact Employees

John W. Michel

Loyola University

Michael J. Kavanagh

State University of New York, Albany

J. Bruce Tracey

Cornell University School of Hotel Administration, jbt6@cornell.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles

Part of the Performance Management Commons

This Article or Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hotel Administration Collection at The Scholarly Commo

been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of The Scholarly Commons. For more information, plea

hotellibrary@cornell.edu.

Recommended Citation

Michel, J. W., Kavanagh, M. J., & Tracey, J. B. (2013). Got support? The impact of supportive work practices on the perceptio

motivation, and behavior of customer-contact employees. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(2), 161-173. doi:10.1177/

1938965512454595

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Got Support? The Impact of Supportive Work Practices on the

Perceptions, Motivation, and Behavior of Customer-Contact Em

Abstract

While scholars know a great deal about the operational challenges faced by customer-contact employ

the hospitality industry, there is much to be learned about the factors associated with the work conte

influences employee motivation, performance, and retention. In this study, the authors examined the

and impact of perceptions about an organization’s customer service climate on ratings of self-efficacy

customer service job performance, and intentions to leave among employees in customer-contact po

Results demonstrated that employees’ perceptions about the climate for service quality were signific

related to motivation, supervisor ratings of service job performance, and self-rated intentions to leave

results offer insights regarding the role of service climate perceptions and the means for effectively m

customer-contact staff and generating higher levels of retention.

Keywords

service climate, motivation, performance, retention

Disciplines

Performance Management

Comments

Required Publisher Statement

© Cornell University. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

This article or chapter is available at The Scholarly Commons: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/8

Perceptions, Motivation, and Behavior of Customer-Contact Em

Abstract

While scholars know a great deal about the operational challenges faced by customer-contact employ

the hospitality industry, there is much to be learned about the factors associated with the work conte

influences employee motivation, performance, and retention. In this study, the authors examined the

and impact of perceptions about an organization’s customer service climate on ratings of self-efficacy

customer service job performance, and intentions to leave among employees in customer-contact po

Results demonstrated that employees’ perceptions about the climate for service quality were signific

related to motivation, supervisor ratings of service job performance, and self-rated intentions to leave

results offer insights regarding the role of service climate perceptions and the means for effectively m

customer-contact staff and generating higher levels of retention.

Keywords

service climate, motivation, performance, retention

Disciplines

Performance Management

Comments

Required Publisher Statement

© Cornell University. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

This article or chapter is available at The Scholarly Commons: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/8

Cornell Hospitality Quarterly

54(2) 161 –173

© The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1938965512454595

http://cqx.sagepub.com

rnell Hospitality Quarterly XX(X)Michel et al.

2012

Numerous factors in the work environment may influence

the extent to which employees in customer-contact posi-

tions are motivated to perform their roles effectively and

remain committed to the organization. In a recent study of

the service and hospitality firms included on Fortune maga-

zine’s list of “best companies to work for,” Hinkin and

Tracey (2010) found that an employee-focused environ-

ment that puts a premium on service quality plays a central

role in distinguishing the firms on this list. Given the critical

role of customer-contact employees in maintaining a high-

quality hospitality environment, it is important to under-

stand the nature and role of employee perceptions about the

work environment that may influence their attitudes, moti-

vation, and performance regarding customer service.

Such perceptions are commonly referred to as service

climate perceptions. In general, service climate refers to

employee perceptions regarding the extent to which service

quality behaviors are rewarded, supported, and expected by

an organization (Schneider and White 2004). Two primary

approaches have been taken to examine the role and impact

of service climate perceptions. The first approach focuses

on the collective impact of perceptions about the work con-

text, typically characterized as organizational service cli-

mate perceptions. Researchers who have utilized this

approach have examined the impact of aggregate-level ser-

vice climate perceptions on various firm- or business-level

measures of performance as well as individual-level out-

comes such as job attitudes, motivation, and job perfor-

mance (e.g., Borucki and Burke 1999; Schneider and White

2004; Way, Sturman, and Raab 2010). The findings have

shown consistently positive relationships between an orga-

nization’s service climate and such outcomes as customer

satisfaction with service quality.

The second approach to understanding the influence of

perceptions about the work context in service firms focuses

on the impact of individual-level or psychological service

climate perceptions. James (1982) argued that climate per-

ceptions are best conceptualized at the psychological level

since these are perceptions of individual employees. In

support of this contention, research has demonstrated a sig-

nificant relationship between psychological climate percep-

tions for service and such important outcomes as employee

affect (Tsai 2001), job satisfaction (Carless 2004), job

1Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA

2Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

3University at Albany, Albany, NY, USA

4Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Corresponding Author:

John W. Michel, Sellinger School of Business & Management, Loyola

University Maryland, 4501 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21210, USA

Email: jwmichel@loyola.edu

Got Support? The Impact of Supportive

Work Practices on the Perceptions,

Motivation, and Behavior of Customer-

Contact Employees

John W. Michel1,2

, Michael J. Kavanagh3, and J. Bruce Tracey4

Abstract

While scholars know a great deal about the operational challenges faced by customer-contact employees in the

industry, there is much to be learned about the factors associated with the work context that influenc

motivation, performance, and retention. In this study, the authors examined the nature and impact of perceptio

an organization’s customer service climate on ratings of self-efficacy, customer service job performance, and in

to leave among employees in customer-contact positions. Results demonstrated that employees’ perceptions a

climate for service quality were significantly related to motivation, supervisor ratings of service job performance

rated intentions to leave. The results offer insights regarding the role of service climate perceptions and the me

effectively managing customer-contact staff and generating higher levels of retention.

Keywords

service climate, motivation, performance, retention

Focus on Human Resources

54(2) 161 –173

© The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1938965512454595

http://cqx.sagepub.com

rnell Hospitality Quarterly XX(X)Michel et al.

2012

Numerous factors in the work environment may influence

the extent to which employees in customer-contact posi-

tions are motivated to perform their roles effectively and

remain committed to the organization. In a recent study of

the service and hospitality firms included on Fortune maga-

zine’s list of “best companies to work for,” Hinkin and

Tracey (2010) found that an employee-focused environ-

ment that puts a premium on service quality plays a central

role in distinguishing the firms on this list. Given the critical

role of customer-contact employees in maintaining a high-

quality hospitality environment, it is important to under-

stand the nature and role of employee perceptions about the

work environment that may influence their attitudes, moti-

vation, and performance regarding customer service.

Such perceptions are commonly referred to as service

climate perceptions. In general, service climate refers to

employee perceptions regarding the extent to which service

quality behaviors are rewarded, supported, and expected by

an organization (Schneider and White 2004). Two primary

approaches have been taken to examine the role and impact

of service climate perceptions. The first approach focuses

on the collective impact of perceptions about the work con-

text, typically characterized as organizational service cli-

mate perceptions. Researchers who have utilized this

approach have examined the impact of aggregate-level ser-

vice climate perceptions on various firm- or business-level

measures of performance as well as individual-level out-

comes such as job attitudes, motivation, and job perfor-

mance (e.g., Borucki and Burke 1999; Schneider and White

2004; Way, Sturman, and Raab 2010). The findings have

shown consistently positive relationships between an orga-

nization’s service climate and such outcomes as customer

satisfaction with service quality.

The second approach to understanding the influence of

perceptions about the work context in service firms focuses

on the impact of individual-level or psychological service

climate perceptions. James (1982) argued that climate per-

ceptions are best conceptualized at the psychological level

since these are perceptions of individual employees. In

support of this contention, research has demonstrated a sig-

nificant relationship between psychological climate percep-

tions for service and such important outcomes as employee

affect (Tsai 2001), job satisfaction (Carless 2004), job

1Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA

2Towson University, Towson, MD, USA

3University at Albany, Albany, NY, USA

4Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

Corresponding Author:

John W. Michel, Sellinger School of Business & Management, Loyola

University Maryland, 4501 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21210, USA

Email: jwmichel@loyola.edu

Got Support? The Impact of Supportive

Work Practices on the Perceptions,

Motivation, and Behavior of Customer-

Contact Employees

John W. Michel1,2

, Michael J. Kavanagh3, and J. Bruce Tracey4

Abstract

While scholars know a great deal about the operational challenges faced by customer-contact employees in the

industry, there is much to be learned about the factors associated with the work context that influenc

motivation, performance, and retention. In this study, the authors examined the nature and impact of perceptio

an organization’s customer service climate on ratings of self-efficacy, customer service job performance, and in

to leave among employees in customer-contact positions. Results demonstrated that employees’ perceptions a

climate for service quality were significantly related to motivation, supervisor ratings of service job performance

rated intentions to leave. The results offer insights regarding the role of service climate perceptions and the me

effectively managing customer-contact staff and generating higher levels of retention.

Keywords

service climate, motivation, performance, retention

Focus on Human Resources

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

162 Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 54(2)

performance (Brown and Leigh 1996), and customer loy-

alty and satisfaction (Johnson 1996).

Positive service climate perceptions are important for

customer-contact employees because they represent the

organization’s image and brand to their customers

(Schneider and White 2004). The provision of good service

by customer-contact employees helps to ensure that cus-

tomers’ service expectations are met. Moreover, inconsis-

tent service delivery due to factors such as high employee

turnover among frontline staff may compromise service

quality (Tracey and Hinkin 2008). While research has sub-

stantiated the relationship between psychological service

climate perceptions and service performance (Borucki and

Burke 1999; Brown and Leigh 1996), it is not clear how

such climate perceptions affect employees’ motivation to

engage in behaviors aimed at providing high-quality service

to customers.

Moreover, little is known about the influence of psycho-

logical service climate perceptions on intentions to leave

among customer-contact employees. Because turnover is an

especially vexing concern in the hospitality industry (Tracey

and Hinkin 2008), it is important to understand the factors

that may ameliorate this problem (Griffeth, Hom, and

Gaertner 2000). Furthermore, most of the service climate

literature has examined the direct effects of climate on indi-

vidual outcomes. It is likely that the relationships between

an individual’s perceptions about the service climate and

customer service job performance are mediated by motiva-

tional factors. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to

examine the relationships among a psychological climate to

support customer service, motivation, customer service job

performance, and intentions to leave among customer-

contact employees.

We begin by discussing previous research on psycho-

logical climate in service and hospitality contexts. Then, we

present the results from a study that examined the relation-

ships between individual climate perceptions among

customer-contact employees and a number of outcome

variables that are critical to maintaining a high-quality ser-

vice environment. Finally, we discuss the implications of

our findings and present some prescriptive guidelines that

may enhance efforts to cultivate a more effective, customer-

centric workplace.

Service Climate

Psychological climate refers to the meanings that people

ascribe to various aspects of their work environment. While

these perceptions can focus on the work environment in

general, they can also be focused on specific aspects of the

work environment (e.g., customer service). For example,

Schneider and his colleagues have demonstrated that per-

ceptions of service climate are significantly related to cus-

tomer perceptions of service quality (Schneider, White, and

Paul 1998). Building on Schneider’s research, Burke,

Borucki, and Hurley (1992) developed a psychological

service climate model that included two primary dimen-

sions: (1) concern for employees and (2) concern for cus-

tomers. This concern-based model stems from employee

perceptions about a wide array of HR policies and practices

that promote effective customer service performance and

morale among customer-contact employees.

Burke, Borucki, and Hurley’s model has been shown to

relate directly to individual sales performance and indi-

rectly to unit-level sales performance through individual

sales performance (Borucki and Burke 1999). While the

Burke, Borucki, and Hurley model provides valuable

insight into the importance of psychological service climate

perceptions, additional research is needed to determine the

impact of such perceptions on various attitudes, motivation,

and performance of customer-contact employees within the

hospitality industry. For example, Brown and Leigh (1996)

demonstrated that employee involvement mediated the rela-

tionship between psychological climate perceptions and job

performance. It is likely that psychological service climate

perceptions and customer service job performance are

mediated by other motivational factors. Furthermore, given

the prevalence of turnover among employees in the hospi-

tality industry, consideration should be given to retention-

related attitudes, particularly an individual’s intention to

leave the firm.

A More Refined Model

Building on the work of Borucki and Burke (1999) and

Tracey and Tews (2005), we contend that a supportive

service climate comprises three main dimensions: human

resource (HR) support, management support, and job sup-

port. It is important to note that our supportive service

climate construct focuses primarily on the importance of

support in service contexts. In fact, Schneider, White, and

Paul (1998, 151) suggested that “a climate for service

rests on a foundation of fundamental support in the way of

resources, training, managerial practices, and the assis-

tance to perform effectively.” Support is important

because it suggests to employees that the organization

values their contribution and cares about their well-being,

which makes them feel more committed and satisfied, less

stressed, and more motivated to perform well (Rhoades

and Eisenberger 2002). As such, we define supportive

service climate as employees’ perceptions that their abil-

ity to provide customers with quality service is supported

by the HR practices utilized by the organization, how

employees are managed, and the way in which employ-

ees’ jobs are designed.

As previously noted, climate perceptions are shaped by

the policies, practices, and procedures that direct employee

behavior at work, including HR practices used by the

performance (Brown and Leigh 1996), and customer loy-

alty and satisfaction (Johnson 1996).

Positive service climate perceptions are important for

customer-contact employees because they represent the

organization’s image and brand to their customers

(Schneider and White 2004). The provision of good service

by customer-contact employees helps to ensure that cus-

tomers’ service expectations are met. Moreover, inconsis-

tent service delivery due to factors such as high employee

turnover among frontline staff may compromise service

quality (Tracey and Hinkin 2008). While research has sub-

stantiated the relationship between psychological service

climate perceptions and service performance (Borucki and

Burke 1999; Brown and Leigh 1996), it is not clear how

such climate perceptions affect employees’ motivation to

engage in behaviors aimed at providing high-quality service

to customers.

Moreover, little is known about the influence of psycho-

logical service climate perceptions on intentions to leave

among customer-contact employees. Because turnover is an

especially vexing concern in the hospitality industry (Tracey

and Hinkin 2008), it is important to understand the factors

that may ameliorate this problem (Griffeth, Hom, and

Gaertner 2000). Furthermore, most of the service climate

literature has examined the direct effects of climate on indi-

vidual outcomes. It is likely that the relationships between

an individual’s perceptions about the service climate and

customer service job performance are mediated by motiva-

tional factors. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to

examine the relationships among a psychological climate to

support customer service, motivation, customer service job

performance, and intentions to leave among customer-

contact employees.

We begin by discussing previous research on psycho-

logical climate in service and hospitality contexts. Then, we

present the results from a study that examined the relation-

ships between individual climate perceptions among

customer-contact employees and a number of outcome

variables that are critical to maintaining a high-quality ser-

vice environment. Finally, we discuss the implications of

our findings and present some prescriptive guidelines that

may enhance efforts to cultivate a more effective, customer-

centric workplace.

Service Climate

Psychological climate refers to the meanings that people

ascribe to various aspects of their work environment. While

these perceptions can focus on the work environment in

general, they can also be focused on specific aspects of the

work environment (e.g., customer service). For example,

Schneider and his colleagues have demonstrated that per-

ceptions of service climate are significantly related to cus-

tomer perceptions of service quality (Schneider, White, and

Paul 1998). Building on Schneider’s research, Burke,

Borucki, and Hurley (1992) developed a psychological

service climate model that included two primary dimen-

sions: (1) concern for employees and (2) concern for cus-

tomers. This concern-based model stems from employee

perceptions about a wide array of HR policies and practices

that promote effective customer service performance and

morale among customer-contact employees.

Burke, Borucki, and Hurley’s model has been shown to

relate directly to individual sales performance and indi-

rectly to unit-level sales performance through individual

sales performance (Borucki and Burke 1999). While the

Burke, Borucki, and Hurley model provides valuable

insight into the importance of psychological service climate

perceptions, additional research is needed to determine the

impact of such perceptions on various attitudes, motivation,

and performance of customer-contact employees within the

hospitality industry. For example, Brown and Leigh (1996)

demonstrated that employee involvement mediated the rela-

tionship between psychological climate perceptions and job

performance. It is likely that psychological service climate

perceptions and customer service job performance are

mediated by other motivational factors. Furthermore, given

the prevalence of turnover among employees in the hospi-

tality industry, consideration should be given to retention-

related attitudes, particularly an individual’s intention to

leave the firm.

A More Refined Model

Building on the work of Borucki and Burke (1999) and

Tracey and Tews (2005), we contend that a supportive

service climate comprises three main dimensions: human

resource (HR) support, management support, and job sup-

port. It is important to note that our supportive service

climate construct focuses primarily on the importance of

support in service contexts. In fact, Schneider, White, and

Paul (1998, 151) suggested that “a climate for service

rests on a foundation of fundamental support in the way of

resources, training, managerial practices, and the assis-

tance to perform effectively.” Support is important

because it suggests to employees that the organization

values their contribution and cares about their well-being,

which makes them feel more committed and satisfied, less

stressed, and more motivated to perform well (Rhoades

and Eisenberger 2002). As such, we define supportive

service climate as employees’ perceptions that their abil-

ity to provide customers with quality service is supported

by the HR practices utilized by the organization, how

employees are managed, and the way in which employ-

ees’ jobs are designed.

As previously noted, climate perceptions are shaped by

the policies, practices, and procedures that direct employee

behavior at work, including HR practices used by the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Michel et al. 163

organization, the behaviors exhibited by managers, and the

ways in which jobs are designed (Bowen and Ostroff 2004).

Accordingly, we argue that when these three workplace

characteristics emphasize support for providing good cus-

tomer service, employees will perceive that they are sup-

ported, rewarded, and expected to provide good service.

Consistent with previous psychological climate research

(James 1982), we argue that the supportive service climate

reflects a single higher-order dimension because each of the

subdimensions focuses on the support given to employees

for providing good service.

HR support for service quality. The first dimension, HR

support for service quality, represents aspects of the organi-

zational system (Tracey and Tews 2005) and is defined as

the extent to which employees perceive that the organiza-

tion’s HR policies and programs demonstrate an emphasis

on supporting its employees in providing high-quality cus-

tomer service. HR support reflects employee-centered HR

practices, such as service-related training programs, sys-

tematic performance appraisals for assessing good per-

formance, and competitive compensation systems for

rewarding good performance and focused on improving

service employees’ job performance and intentions to

remain with the organization (Cheng-Hua, Shyh-Jer, and

Shih-Chien 2009; Nishii, Lepak, and Schneider 2008).

These HR practices suggest to employees that the organiza-

tion will ensure they have the skills, resources, and motiva-

tion needed to adapt to various customer demands and

provide effective customer service (Kusluvan et al. 2010).

HR support is similar to two aspects from Burke, Borucki,

and Hurley’s (1992) framework: monetary reward orienta-

tion and means emphasis.

Management support for service quality. Management sup-

port for service quality represents a major part of the orga-

nization’s social support system (Tracey and Tews 2005).

This dimension is defined as the extent to which employees

perceive that managers both encourage and reinforce the

delivery of high-quality customer service and provide sup-

port to ensure the customers’ and employees’ needs are

met. As such, it reflects the extent to which managers

emphasize service quality (Susskind, Kacmar, and Borch-

grevink 2007). By setting service-related goals, providing

recognition and rewards to employees for providing good

service, and removing obstacles that prevent employees

from effectively serving customers, managers send clear

signals to employees that managers will give them the sup-

port necessary to provide good customer service (Clark,

Hartline, and Jones 2009; Hinkin and Schriesheim 2004).

Management support is similar to three aspects from Burke,

Borucki, and Hurley’s framework: nonmonetary reward ori-

entation, goal emphasis, and management support.

Job support for service quality. Job support for service

quality represents work-related and technical system factors

(Tracey and Tews 2005). This dimension is defined as the

extent to which employees perceive that jobs are designed

to promote high-quality customer service by providing the

tools, equipment, and staff necessary to support employees

in the provision of good customer service. When organiza-

tions design jobs in a way that helps employees serve cus-

tomers, employees perceive that the organization wants to

make it possible for them to provide good customer service.

According to both the service-profit chain and service cli-

mate frameworks, the manner in which the job is designed

and the extent to which customer-contact employees have

the necessary resources can have a substantial impact on an

employee’s capacity for delivering high-quality customer

service (Heskett, Sasser, and Schlesinger 1997; Schneider,

White, and Paul 1998). Job support is similar to two aspects

from Burke, Borucki, and Hurley’s framework, HR-related

obstacles and merchandise-related obstacles, except that we

are considering job support practices that facilitate service,

rather than the obstacles that impair service quality.

Supportive Service Climate

and Customer Service Performance

Customer service performance includes job behaviors that

service employees perform to drive customers’ perceptions

of service quality and satisfaction (Ryan and Ployhart

2003). These behaviors are directed at customers with the

intention of benefiting or helping the customer, and as a

result they represent a form of prosocial organizational

behavior comprising both in-role and extrarole forms of

behavior (George 1991).

Research suggests that employees tend to perform better

when they perceive that the organization demonstrates con-

cern through the provision of various forms of work-related

support. For example, Borucki and Burke (1999) demon-

strated that a concern for employees was related to unit-

level service performance. Similarly, researchers have

shown that related constructs such as perceived organiza-

tional support (POS; Bettencourt, Gwinner, and Meuter

2001), equipment and supply support (Schneider and White

2004), and high-commitment HR practices (Nishii, Lepak,

and Schneider 2008) are related to service performance. By

utilizing supportive HR practices, such as service-related

training and performance incentives for providing good ser-

vice, organizations can provide employees with the skills

and resources necessary for providing high-quality service

(Liao and Chuang 2004). Similarly, when supportive man-

agers set service-related goals, provide recognition to

employees when they provide good service, help employ-

ees work together, and remove obstacles that prevent them

from providing good service, they send clear signals regard-

ing the importance of high-quality service (Schneider, White,

and Paul 1998). Finally, designing jobs that ensure employ-

ees have the necessary tools, resources, and staff to handle

customer demands helps employees deliver high-quality

organization, the behaviors exhibited by managers, and the

ways in which jobs are designed (Bowen and Ostroff 2004).

Accordingly, we argue that when these three workplace

characteristics emphasize support for providing good cus-

tomer service, employees will perceive that they are sup-

ported, rewarded, and expected to provide good service.

Consistent with previous psychological climate research

(James 1982), we argue that the supportive service climate

reflects a single higher-order dimension because each of the

subdimensions focuses on the support given to employees

for providing good service.

HR support for service quality. The first dimension, HR

support for service quality, represents aspects of the organi-

zational system (Tracey and Tews 2005) and is defined as

the extent to which employees perceive that the organiza-

tion’s HR policies and programs demonstrate an emphasis

on supporting its employees in providing high-quality cus-

tomer service. HR support reflects employee-centered HR

practices, such as service-related training programs, sys-

tematic performance appraisals for assessing good per-

formance, and competitive compensation systems for

rewarding good performance and focused on improving

service employees’ job performance and intentions to

remain with the organization (Cheng-Hua, Shyh-Jer, and

Shih-Chien 2009; Nishii, Lepak, and Schneider 2008).

These HR practices suggest to employees that the organiza-

tion will ensure they have the skills, resources, and motiva-

tion needed to adapt to various customer demands and

provide effective customer service (Kusluvan et al. 2010).

HR support is similar to two aspects from Burke, Borucki,

and Hurley’s (1992) framework: monetary reward orienta-

tion and means emphasis.

Management support for service quality. Management sup-

port for service quality represents a major part of the orga-

nization’s social support system (Tracey and Tews 2005).

This dimension is defined as the extent to which employees

perceive that managers both encourage and reinforce the

delivery of high-quality customer service and provide sup-

port to ensure the customers’ and employees’ needs are

met. As such, it reflects the extent to which managers

emphasize service quality (Susskind, Kacmar, and Borch-

grevink 2007). By setting service-related goals, providing

recognition and rewards to employees for providing good

service, and removing obstacles that prevent employees

from effectively serving customers, managers send clear

signals to employees that managers will give them the sup-

port necessary to provide good customer service (Clark,

Hartline, and Jones 2009; Hinkin and Schriesheim 2004).

Management support is similar to three aspects from Burke,

Borucki, and Hurley’s framework: nonmonetary reward ori-

entation, goal emphasis, and management support.

Job support for service quality. Job support for service

quality represents work-related and technical system factors

(Tracey and Tews 2005). This dimension is defined as the

extent to which employees perceive that jobs are designed

to promote high-quality customer service by providing the

tools, equipment, and staff necessary to support employees

in the provision of good customer service. When organiza-

tions design jobs in a way that helps employees serve cus-

tomers, employees perceive that the organization wants to

make it possible for them to provide good customer service.

According to both the service-profit chain and service cli-

mate frameworks, the manner in which the job is designed

and the extent to which customer-contact employees have

the necessary resources can have a substantial impact on an

employee’s capacity for delivering high-quality customer

service (Heskett, Sasser, and Schlesinger 1997; Schneider,

White, and Paul 1998). Job support is similar to two aspects

from Burke, Borucki, and Hurley’s framework, HR-related

obstacles and merchandise-related obstacles, except that we

are considering job support practices that facilitate service,

rather than the obstacles that impair service quality.

Supportive Service Climate

and Customer Service Performance

Customer service performance includes job behaviors that

service employees perform to drive customers’ perceptions

of service quality and satisfaction (Ryan and Ployhart

2003). These behaviors are directed at customers with the

intention of benefiting or helping the customer, and as a

result they represent a form of prosocial organizational

behavior comprising both in-role and extrarole forms of

behavior (George 1991).

Research suggests that employees tend to perform better

when they perceive that the organization demonstrates con-

cern through the provision of various forms of work-related

support. For example, Borucki and Burke (1999) demon-

strated that a concern for employees was related to unit-

level service performance. Similarly, researchers have

shown that related constructs such as perceived organiza-

tional support (POS; Bettencourt, Gwinner, and Meuter

2001), equipment and supply support (Schneider and White

2004), and high-commitment HR practices (Nishii, Lepak,

and Schneider 2008) are related to service performance. By

utilizing supportive HR practices, such as service-related

training and performance incentives for providing good ser-

vice, organizations can provide employees with the skills

and resources necessary for providing high-quality service

(Liao and Chuang 2004). Similarly, when supportive man-

agers set service-related goals, provide recognition to

employees when they provide good service, help employ-

ees work together, and remove obstacles that prevent them

from providing good service, they send clear signals regard-

ing the importance of high-quality service (Schneider, White,

and Paul 1998). Finally, designing jobs that ensure employ-

ees have the necessary tools, resources, and staff to handle

customer demands helps employees deliver high-quality

164 Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 54(2)

service (Heskett, Sasser, and Schlesinger 1997). These

practices suggest to employees that they have the support

necessary to provide good customer service; therefore, we

hypothesize the following relationship:

Hypothesis 1: Supportive service climate is positively

related to service performance.

Supportive Service Climate

and Intentions to Leave

Given that turnover is an important concern and that inten-

tions to leave have been shown to be related to actual turn-

over, researchers often focus on intentions to leave (Fishbein

and Ajzen 1975). An employee who reports greater leave

intentions is in fact more likely to leave, and measures of

intentions to leave have been empirically related to actual

turnover (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner 2000). Because

customer-contact employees represent the organization’s

image and brand to their customers, high turnover among

these employees substantially increases costs and compro-

mises service quality (Tracey and Hinkin 2008). Such

turnover may ultimately have a negative impact on cus-

tomer satisfaction and loyalty (Batt 2002).

While little evidence demonstrating the relationship

between psychological climate and intentions to leave

exists, researchers have shown a negative relationship

between similar constructs and turnover. For example,

Shaw et al. (1998) found that high-commitment HR prac-

tices were negatively associated with voluntary turnover.

Similarly, Ng and Sorensen (2008) demonstrated that when

managers provide recognition to employees, motivate

employees to work together, and remove obstacles prevent-

ing effective performance, employees feel more obligated

to stay with the company. Furthermore, providing the nec-

essary tools and resources to employees enables them to

respond effectively to customer demands, but also creates a

more flexible, multifunctional internal workforce that can

adapt quickly to the constantly shifting competitive land-

scape. These practices suggest to employees that the organi-

zation values their contribution and wants them to succeed;

therefore, we hypothesize,

Hypothesis 2: Supportive service climate is negatively

related to intentions to leave.

The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Service environments that emphasize HR, management,

and job support for service quality should promote employee

self-efficacy regarding customer service performance

(Maurer, Pierce, and Shore 2002). Self-efficacy is a per-

son’s belief about whether he or she can successfully per-

form a specific task (Bandura 1986). According to Gist and

Mitchell (1992), self-efficacy is an important motivational

construct because it influences (1) goal level and commit-

ment, (2) choice of activity, and (3) interpretation of feed-

back. Bandura has suggested that self-efficacy is predicted

by positive emotional support, models of success with

which people identify, and experience mastering a task.

Employees’ perceived capabilities to effectively perform

their jobs, their sense of self-worth, their confidence, and

their belief that their work is important and meaningful can

be enhanced through the use of organizational practices

such as the provision of developmental training, financial

reinforcements, high performance expectations and feed-

back, and the resources necessary to perform their jobs

(Liao et al. 2009). Furthermore, self-efficacy has been

shown to improve the personal mastery or “can-do” atti-

tude of service employees (Liao and Chuang 2007) moti-

vating them to work harder, display more effort, and

perform better in demanding situations with customers

(Ahearne, Mathieu, and Rapp 2005). Therefore, we hypoth-

esize the following relationship:

Hypothesis 3: Self-efficacy mediates the supportive ser-

vice climate and service performance relationship.

Research has also demonstrated a negative relationship

between self-efficacy and intentions to leave (Martin, Jones,

and Callan 2005). People with higher self-efficacy experi-

ence less self-doubt and undertake new challenges at work

(Wood and Bandura 1989). As stated previously, the sup-

port from HR practices, managerial behaviors, and effec-

tive job design will help employees develop a sense of

self-worth and confidence in their ability to perform their

job. Employees should have less self-doubt about their job

performance and consequently will be less likely to want to

leave the organization. Therefore, we hypothesize the fol-

lowing relationship:

Hypothesis 4: Self-efficacy mediates the supportive

service climate and intentions to leave relationship.

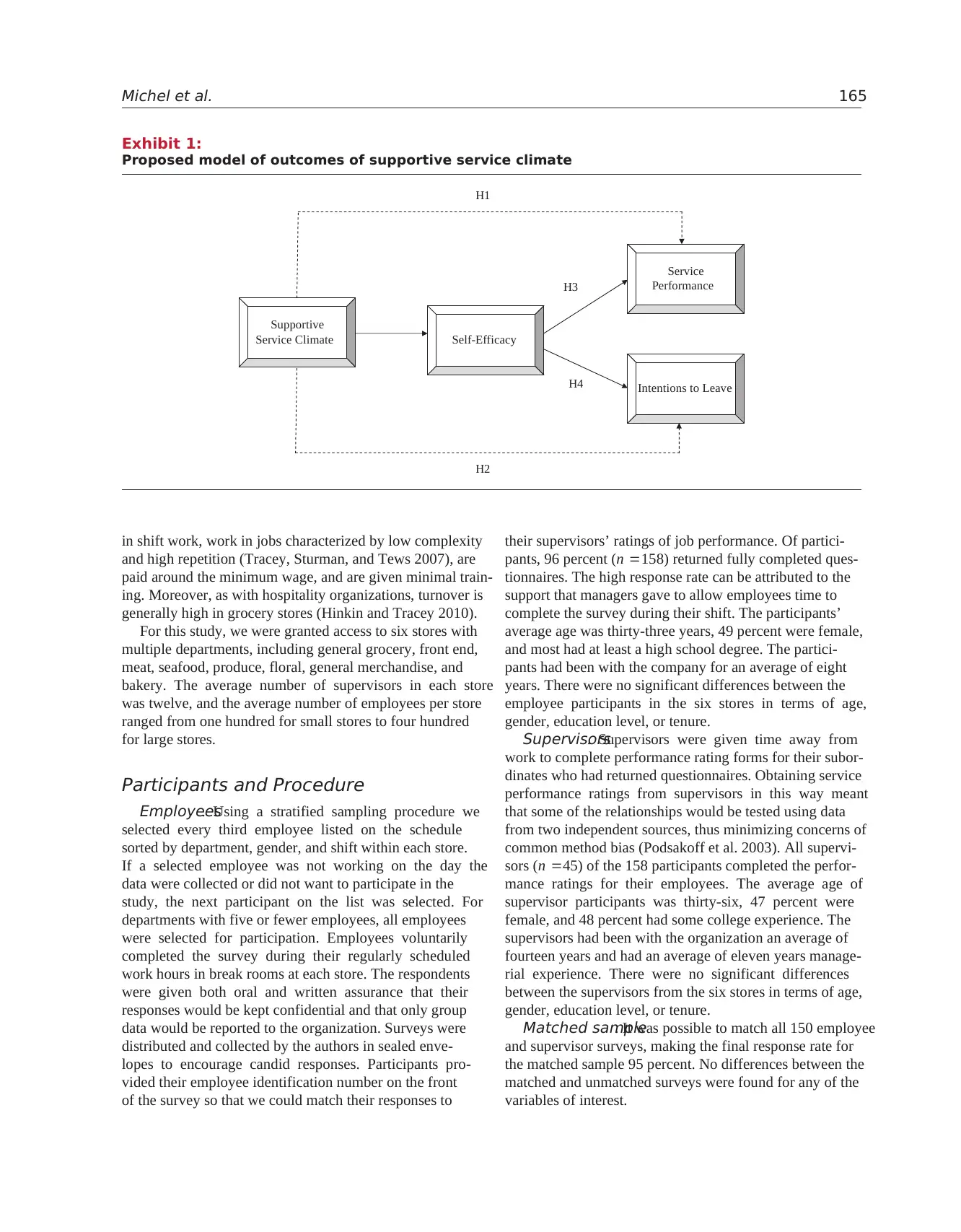

The hypothesized relationships tested in this study are

depicted in Exhibit 1.

Method

Organizational Setting

The sponsor for our study was a company that owns and

operates 119 grocery stores in six states in the northeastern

United States. While grocery stores may not represent a

traditional hospitality context, they are quite similar to

hotels and restaurants in several respects (cf. Hinkin and

Tracey 2010). In particular, grocery store employees have

direct and significant interactions with customers, engage

service (Heskett, Sasser, and Schlesinger 1997). These

practices suggest to employees that they have the support

necessary to provide good customer service; therefore, we

hypothesize the following relationship:

Hypothesis 1: Supportive service climate is positively

related to service performance.

Supportive Service Climate

and Intentions to Leave

Given that turnover is an important concern and that inten-

tions to leave have been shown to be related to actual turn-

over, researchers often focus on intentions to leave (Fishbein

and Ajzen 1975). An employee who reports greater leave

intentions is in fact more likely to leave, and measures of

intentions to leave have been empirically related to actual

turnover (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner 2000). Because

customer-contact employees represent the organization’s

image and brand to their customers, high turnover among

these employees substantially increases costs and compro-

mises service quality (Tracey and Hinkin 2008). Such

turnover may ultimately have a negative impact on cus-

tomer satisfaction and loyalty (Batt 2002).

While little evidence demonstrating the relationship

between psychological climate and intentions to leave

exists, researchers have shown a negative relationship

between similar constructs and turnover. For example,

Shaw et al. (1998) found that high-commitment HR prac-

tices were negatively associated with voluntary turnover.

Similarly, Ng and Sorensen (2008) demonstrated that when

managers provide recognition to employees, motivate

employees to work together, and remove obstacles prevent-

ing effective performance, employees feel more obligated

to stay with the company. Furthermore, providing the nec-

essary tools and resources to employees enables them to

respond effectively to customer demands, but also creates a

more flexible, multifunctional internal workforce that can

adapt quickly to the constantly shifting competitive land-

scape. These practices suggest to employees that the organi-

zation values their contribution and wants them to succeed;

therefore, we hypothesize,

Hypothesis 2: Supportive service climate is negatively

related to intentions to leave.

The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Service environments that emphasize HR, management,

and job support for service quality should promote employee

self-efficacy regarding customer service performance

(Maurer, Pierce, and Shore 2002). Self-efficacy is a per-

son’s belief about whether he or she can successfully per-

form a specific task (Bandura 1986). According to Gist and

Mitchell (1992), self-efficacy is an important motivational

construct because it influences (1) goal level and commit-

ment, (2) choice of activity, and (3) interpretation of feed-

back. Bandura has suggested that self-efficacy is predicted

by positive emotional support, models of success with

which people identify, and experience mastering a task.

Employees’ perceived capabilities to effectively perform

their jobs, their sense of self-worth, their confidence, and

their belief that their work is important and meaningful can

be enhanced through the use of organizational practices

such as the provision of developmental training, financial

reinforcements, high performance expectations and feed-

back, and the resources necessary to perform their jobs

(Liao et al. 2009). Furthermore, self-efficacy has been

shown to improve the personal mastery or “can-do” atti-

tude of service employees (Liao and Chuang 2007) moti-

vating them to work harder, display more effort, and

perform better in demanding situations with customers

(Ahearne, Mathieu, and Rapp 2005). Therefore, we hypoth-

esize the following relationship:

Hypothesis 3: Self-efficacy mediates the supportive ser-

vice climate and service performance relationship.

Research has also demonstrated a negative relationship

between self-efficacy and intentions to leave (Martin, Jones,

and Callan 2005). People with higher self-efficacy experi-

ence less self-doubt and undertake new challenges at work

(Wood and Bandura 1989). As stated previously, the sup-

port from HR practices, managerial behaviors, and effec-

tive job design will help employees develop a sense of

self-worth and confidence in their ability to perform their

job. Employees should have less self-doubt about their job

performance and consequently will be less likely to want to

leave the organization. Therefore, we hypothesize the fol-

lowing relationship:

Hypothesis 4: Self-efficacy mediates the supportive

service climate and intentions to leave relationship.

The hypothesized relationships tested in this study are

depicted in Exhibit 1.

Method

Organizational Setting

The sponsor for our study was a company that owns and

operates 119 grocery stores in six states in the northeastern

United States. While grocery stores may not represent a

traditional hospitality context, they are quite similar to

hotels and restaurants in several respects (cf. Hinkin and

Tracey 2010). In particular, grocery store employees have

direct and significant interactions with customers, engage

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Michel et al. 165

in shift work, work in jobs characterized by low complexity

and high repetition (Tracey, Sturman, and Tews 2007), are

paid around the minimum wage, and are given minimal train-

ing. Moreover, as with hospitality organizations, turnover is

generally high in grocery stores (Hinkin and Tracey 2010).

For this study, we were granted access to six stores with

multiple departments, including general grocery, front end,

meat, seafood, produce, floral, general merchandise, and

bakery. The average number of supervisors in each store

was twelve, and the average number of employees per store

ranged from one hundred for small stores to four hundred

for large stores.

Participants and Procedure

Employees. Using a stratified sampling procedure we

selected every third employee listed on the schedule

sorted by department, gender, and shift within each store.

If a selected employee was not working on the day the

data were collected or did not want to participate in the

study, the next participant on the list was selected. For

departments with five or fewer employees, all employees

were selected for participation. Employees voluntarily

completed the survey during their regularly scheduled

work hours in break rooms at each store. The respondents

were given both oral and written assurance that their

responses would be kept confidential and that only group

data would be reported to the organization. Surveys were

distributed and collected by the authors in sealed enve-

lopes to encourage candid responses. Participants pro-

vided their employee identification number on the front

of the survey so that we could match their responses to

their supervisors’ ratings of job performance. Of partici-

pants, 96 percent (n =158) returned fully completed ques-

tionnaires. The high response rate can be attributed to the

support that managers gave to allow employees time to

complete the survey during their shift. The participants’

average age was thirty-three years, 49 percent were female,

and most had at least a high school degree. The partici-

pants had been with the company for an average of eight

years. There were no significant differences between the

employee participants in the six stores in terms of age,

gender, education level, or tenure.

Supervisors. Supervisors were given time away from

work to complete performance rating forms for their subor-

dinates who had returned questionnaires. Obtaining service

performance ratings from supervisors in this way meant

that some of the relationships would be tested using data

from two independent sources, thus minimizing concerns of

common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). All supervi-

sors (n =45) of the 158 participants completed the perfor-

mance ratings for their employees. The average age of

supervisor participants was thirty-six, 47 percent were

female, and 48 percent had some college experience. The

supervisors had been with the organization an average of

fourteen years and had an average of eleven years manage-

rial experience. There were no significant differences

between the supervisors from the six stores in terms of age,

gender, education level, or tenure.

Matched sample. It was possible to match all 150 employee

and supervisor surveys, making the final response rate for

the matched sample 95 percent. No differences between the

matched and unmatched surveys were found for any of the

variables of interest.

Exhibit 1:

Proposed model of outcomes of supportive service climate

Supportive

Service Climate Self-Efficacy

Service

Performance

Intentions to Leave

H1

H2

H3

H4

in shift work, work in jobs characterized by low complexity

and high repetition (Tracey, Sturman, and Tews 2007), are

paid around the minimum wage, and are given minimal train-

ing. Moreover, as with hospitality organizations, turnover is

generally high in grocery stores (Hinkin and Tracey 2010).

For this study, we were granted access to six stores with

multiple departments, including general grocery, front end,

meat, seafood, produce, floral, general merchandise, and

bakery. The average number of supervisors in each store

was twelve, and the average number of employees per store

ranged from one hundred for small stores to four hundred

for large stores.

Participants and Procedure

Employees. Using a stratified sampling procedure we

selected every third employee listed on the schedule

sorted by department, gender, and shift within each store.

If a selected employee was not working on the day the

data were collected or did not want to participate in the

study, the next participant on the list was selected. For

departments with five or fewer employees, all employees

were selected for participation. Employees voluntarily

completed the survey during their regularly scheduled

work hours in break rooms at each store. The respondents

were given both oral and written assurance that their

responses would be kept confidential and that only group

data would be reported to the organization. Surveys were

distributed and collected by the authors in sealed enve-

lopes to encourage candid responses. Participants pro-

vided their employee identification number on the front

of the survey so that we could match their responses to

their supervisors’ ratings of job performance. Of partici-

pants, 96 percent (n =158) returned fully completed ques-

tionnaires. The high response rate can be attributed to the

support that managers gave to allow employees time to

complete the survey during their shift. The participants’

average age was thirty-three years, 49 percent were female,

and most had at least a high school degree. The partici-

pants had been with the company for an average of eight

years. There were no significant differences between the

employee participants in the six stores in terms of age,

gender, education level, or tenure.

Supervisors. Supervisors were given time away from

work to complete performance rating forms for their subor-

dinates who had returned questionnaires. Obtaining service

performance ratings from supervisors in this way meant

that some of the relationships would be tested using data

from two independent sources, thus minimizing concerns of

common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). All supervi-

sors (n =45) of the 158 participants completed the perfor-

mance ratings for their employees. The average age of

supervisor participants was thirty-six, 47 percent were

female, and 48 percent had some college experience. The

supervisors had been with the organization an average of

fourteen years and had an average of eleven years manage-

rial experience. There were no significant differences

between the supervisors from the six stores in terms of age,

gender, education level, or tenure.

Matched sample. It was possible to match all 150 employee

and supervisor surveys, making the final response rate for

the matched sample 95 percent. No differences between the

matched and unmatched surveys were found for any of the

variables of interest.

Exhibit 1:

Proposed model of outcomes of supportive service climate

Supportive

Service Climate Self-Efficacy

Service

Performance

Intentions to Leave

H1

H2

H3

H4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

166 Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 54(2)

Measures

Supportive service climate. We developed the supportive

service climate questionnaire using scale development pro-

cedures suggested by Hinkin (1998) and others. Twenty-

one items were chosen from the extant literature to reflect

the three constructs and adapted to reflect support for ser-

vice quality. Survey items reflected the three first-order fac-

tors, namely, HR support, management support, and job

support, according to what happens in their organization

and work unit. Responses in this and other sections were

made on 7-point Likert-type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly

disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The HR support dimension included six adapted items

from Tracey and Tews (2005) and one item from Lytle,

Hom, and Mokwa (1998). A sample item for HR support is,

“There are rewards and incentives for providing high qual-

ity service to customers.” The management support dimen-

sion was measured using five items adapted from Schneider

et al. (2000), one item adapted from Schneider, White, and

Paul (1998), and one item adapted from Tracey and Tews

(2005). A sample item for management support is, “My

manager sets definite quality standards of good customer

service.” The job support dimension was measured using

seven items adapted from Schneider, White, and Paul

(1998). A sample item for job support is, “We have suffi-

cient staff in my work unit to deliver high-quality service to

customers.”

The fit of a higher-order supportive service climate

model, in which the three first-order factors were fit to a

second-order factor, was compared to a single-factor model

with Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2007) using the sam-

ple covariance matrix as input and a maximum likelihood

solution. Three item parcels were created as indicators of

each latent construct in the model by randomly assigning

the items to parcels, which allowed us to maintain an ade-

quate sample size to parameter ratio (Little et al. 2002).1

The overall chi-square test of the higher-order model was

significant, χ2(24, N =158) =53.21, p < .01; however, the

individual fit indexes provided support for the proposed

model—the comparative fit index (CFI) was .97, the root

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was .09, and

the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was .04

(Hu and Bentler 1999). Despite the high correlations among

the first-order factors (r =.81 to r =.86), the single-factor

model did not fit the data well, χ 2(27, N =158) =127.38,

p < .001, CFI =.89, RMSEA =.15, and SRMR =.06, and

was a worse fit (χ2

Difference (3) =74.17, p < .001) than the pro-

posed model. The supportive service climate model’s com-

posite reliability was .87.

Service self-efficacy beliefs. Employee self-efficacy was

measured using a reduced eight-item version of the self-

efficacy scale from Phillips and Gully (1997). These items

were adapted to reflect employees’ perceptions of their

self-efficacy for providing high-quality service to custom-

ers. An example item is, “I feel confident in my ability to

effectively provide high quality service to customers.”

Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .81

Intentions to leave. Employee intentions to leave were

measured with the six-item Staying or Leaving Index devel-

oped by Bluedorn (1982). The six items formed one turn-

over intention scale; however, to minimize response bias,

the two sets of items were located in two different sections

of the survey, as recommended by Bluedorn. Placed in the

beginning of the survey were three items asking partici-

pants to rate their chances of working with the organization

three, six, and twelve months from now. The other three

items, which asked participants to rate their chances of

leaving the organization three, six, and twelve months from

now, were placed at the end of the survey. Participants rated

these six items on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very

unlikely) to 7 (very likely). Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Control variables. Control variables in the regression anal-

ysis included demographic variables such as gender, age,

highest level of education. We also controlled for work shift

because the organization’s management explained that the

shift a person works is determined by his or her organiza-

tional tenure and job performance, and the most desirable

shift is the day shift. We also controlled for organizational

tenure because we felt that those who had been with the

organization longer remain employed because they are bet-

ter performers and thus would have fewer intentions

of leaving because they have more invested into the

organization.

Customer service job performance. Supervisors were asked

to rate the customer service performance of each participat-

ing employee in the previous six months based on the

frequency with which they displayed behaviors on a twelve-

item multidimensional customer-centered behavior (CCB)

measure, which has been found to have good psychometric

qualities (Michel, Tews, and Kavanagh 2010). The measure

consists of one second-order dimension and three first order

dimensions of customer service behavior—customer assur-

ance behaviors (four items; α = .92), customer respon-

siveness behaviors (four items; α = .90), and customer

recommendation behaviors (four items; α =.88). Example

items include “Acknowledges customers’ presence promptly”

and “Offers substitutes for services or products not cur-

rently available.” These behaviors were rated on a scale

ranging from 1 (the employee has engaged in the behavior

0–44 percent of the time) to 7 (the employee has engaged in

the behavior 95–100 percent of the time). The CCB’s com-

posite reliability was .92.

Analyses

Prior to assessing the hypothesized relationships, it

was important to determine whether supportive service

Measures

Supportive service climate. We developed the supportive

service climate questionnaire using scale development pro-

cedures suggested by Hinkin (1998) and others. Twenty-

one items were chosen from the extant literature to reflect

the three constructs and adapted to reflect support for ser-

vice quality. Survey items reflected the three first-order fac-

tors, namely, HR support, management support, and job

support, according to what happens in their organization

and work unit. Responses in this and other sections were

made on 7-point Likert-type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly

disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The HR support dimension included six adapted items

from Tracey and Tews (2005) and one item from Lytle,

Hom, and Mokwa (1998). A sample item for HR support is,

“There are rewards and incentives for providing high qual-

ity service to customers.” The management support dimen-

sion was measured using five items adapted from Schneider

et al. (2000), one item adapted from Schneider, White, and

Paul (1998), and one item adapted from Tracey and Tews

(2005). A sample item for management support is, “My

manager sets definite quality standards of good customer

service.” The job support dimension was measured using

seven items adapted from Schneider, White, and Paul

(1998). A sample item for job support is, “We have suffi-

cient staff in my work unit to deliver high-quality service to

customers.”

The fit of a higher-order supportive service climate

model, in which the three first-order factors were fit to a

second-order factor, was compared to a single-factor model

with Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2007) using the sam-

ple covariance matrix as input and a maximum likelihood

solution. Three item parcels were created as indicators of

each latent construct in the model by randomly assigning

the items to parcels, which allowed us to maintain an ade-

quate sample size to parameter ratio (Little et al. 2002).1

The overall chi-square test of the higher-order model was

significant, χ2(24, N =158) =53.21, p < .01; however, the

individual fit indexes provided support for the proposed

model—the comparative fit index (CFI) was .97, the root

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was .09, and

the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was .04

(Hu and Bentler 1999). Despite the high correlations among

the first-order factors (r =.81 to r =.86), the single-factor

model did not fit the data well, χ 2(27, N =158) =127.38,

p < .001, CFI =.89, RMSEA =.15, and SRMR =.06, and

was a worse fit (χ2

Difference (3) =74.17, p < .001) than the pro-

posed model. The supportive service climate model’s com-

posite reliability was .87.

Service self-efficacy beliefs. Employee self-efficacy was

measured using a reduced eight-item version of the self-

efficacy scale from Phillips and Gully (1997). These items

were adapted to reflect employees’ perceptions of their

self-efficacy for providing high-quality service to custom-

ers. An example item is, “I feel confident in my ability to

effectively provide high quality service to customers.”

Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .81

Intentions to leave. Employee intentions to leave were

measured with the six-item Staying or Leaving Index devel-

oped by Bluedorn (1982). The six items formed one turn-

over intention scale; however, to minimize response bias,

the two sets of items were located in two different sections

of the survey, as recommended by Bluedorn. Placed in the

beginning of the survey were three items asking partici-

pants to rate their chances of working with the organization

three, six, and twelve months from now. The other three

items, which asked participants to rate their chances of

leaving the organization three, six, and twelve months from

now, were placed at the end of the survey. Participants rated

these six items on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very

unlikely) to 7 (very likely). Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Control variables. Control variables in the regression anal-

ysis included demographic variables such as gender, age,

highest level of education. We also controlled for work shift

because the organization’s management explained that the

shift a person works is determined by his or her organiza-

tional tenure and job performance, and the most desirable

shift is the day shift. We also controlled for organizational

tenure because we felt that those who had been with the

organization longer remain employed because they are bet-

ter performers and thus would have fewer intentions

of leaving because they have more invested into the

organization.

Customer service job performance. Supervisors were asked

to rate the customer service performance of each participat-

ing employee in the previous six months based on the

frequency with which they displayed behaviors on a twelve-

item multidimensional customer-centered behavior (CCB)

measure, which has been found to have good psychometric

qualities (Michel, Tews, and Kavanagh 2010). The measure

consists of one second-order dimension and three first order

dimensions of customer service behavior—customer assur-

ance behaviors (four items; α = .92), customer respon-

siveness behaviors (four items; α = .90), and customer

recommendation behaviors (four items; α =.88). Example

items include “Acknowledges customers’ presence promptly”

and “Offers substitutes for services or products not cur-

rently available.” These behaviors were rated on a scale

ranging from 1 (the employee has engaged in the behavior

0–44 percent of the time) to 7 (the employee has engaged in

the behavior 95–100 percent of the time). The CCB’s com-

posite reliability was .92.

Analyses

Prior to assessing the hypothesized relationships, it

was important to determine whether supportive service

Michel et al. 167

climate was best reflected at the individual or unit level of

analysis prior to testing the hypotheses (Borucki and Burke

1999).2 Three estimates, ICC(1), ICC(2), and rwg(j), were

calculated to assess the statistical justification for aggregat-

ing these data. The ICC(1) indicates the amount of variance

explained between units compared to total variance. The

ICC(2) is an assessment of reliability of the group means.

The F test associated with these analyses indicates whether

the individual-level responses differ significantly by groups.

In addition, the r wg(j) statistic was computed to provide an

estimate of interrater agreement within each department

(James 1982).

There was no meaningful between-group variance for

the supportive service climate construct. The F and intra-

class correlation values for supportive service climate,

F(46, 111) =1.42, p =ns, ICC(1) =.11, ICC(2) =.29, were

well below the values typically considered acceptable in

organizational research (Bliese 2000). The median rwg(j) for

supportive service climate was .52, which is below the .70

cutoff discussed by James (1982), indicating low agreement

among employees within each department. As such, these

analyses do not support aggregating the supportive service

climate construct to the department level.

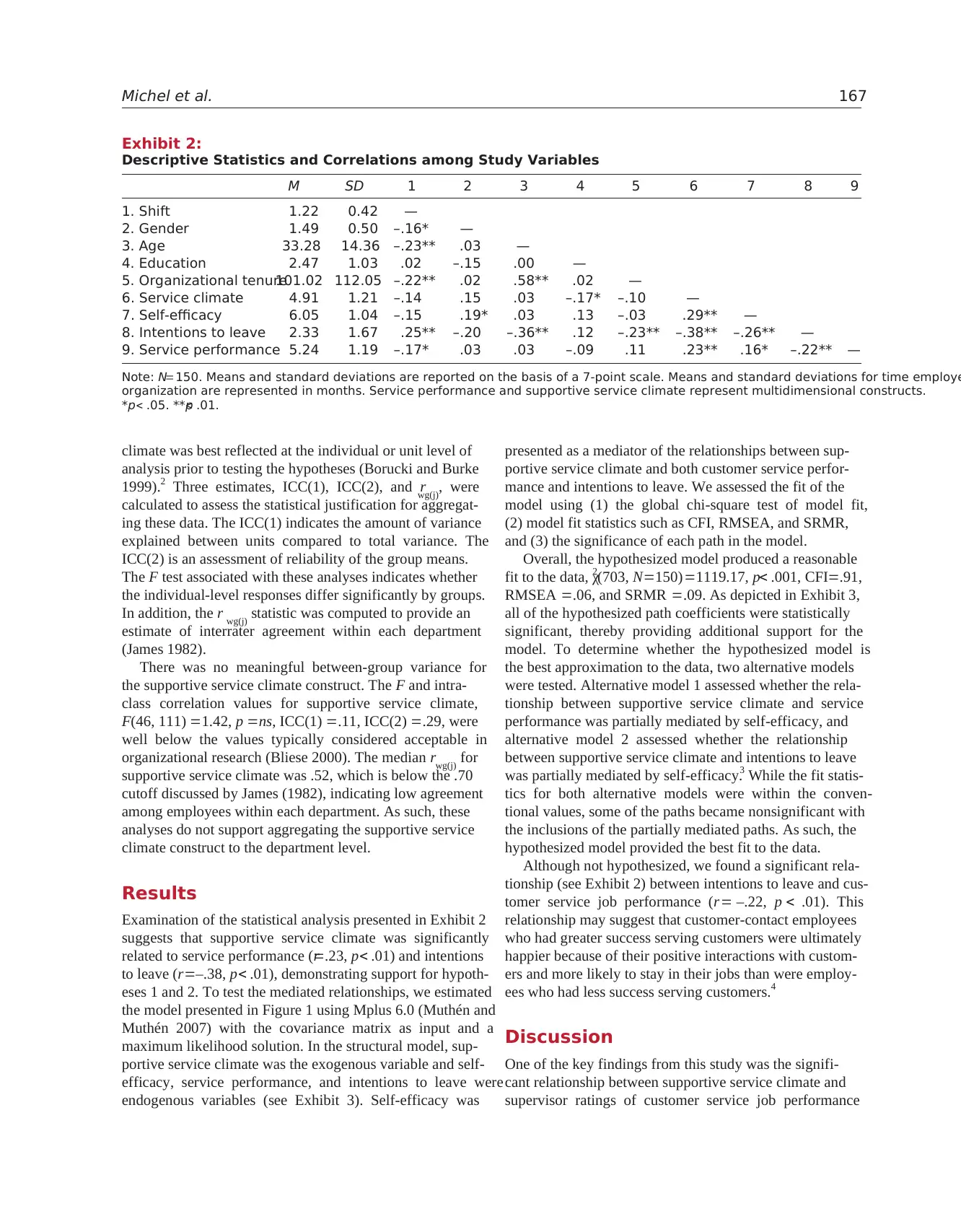

Results

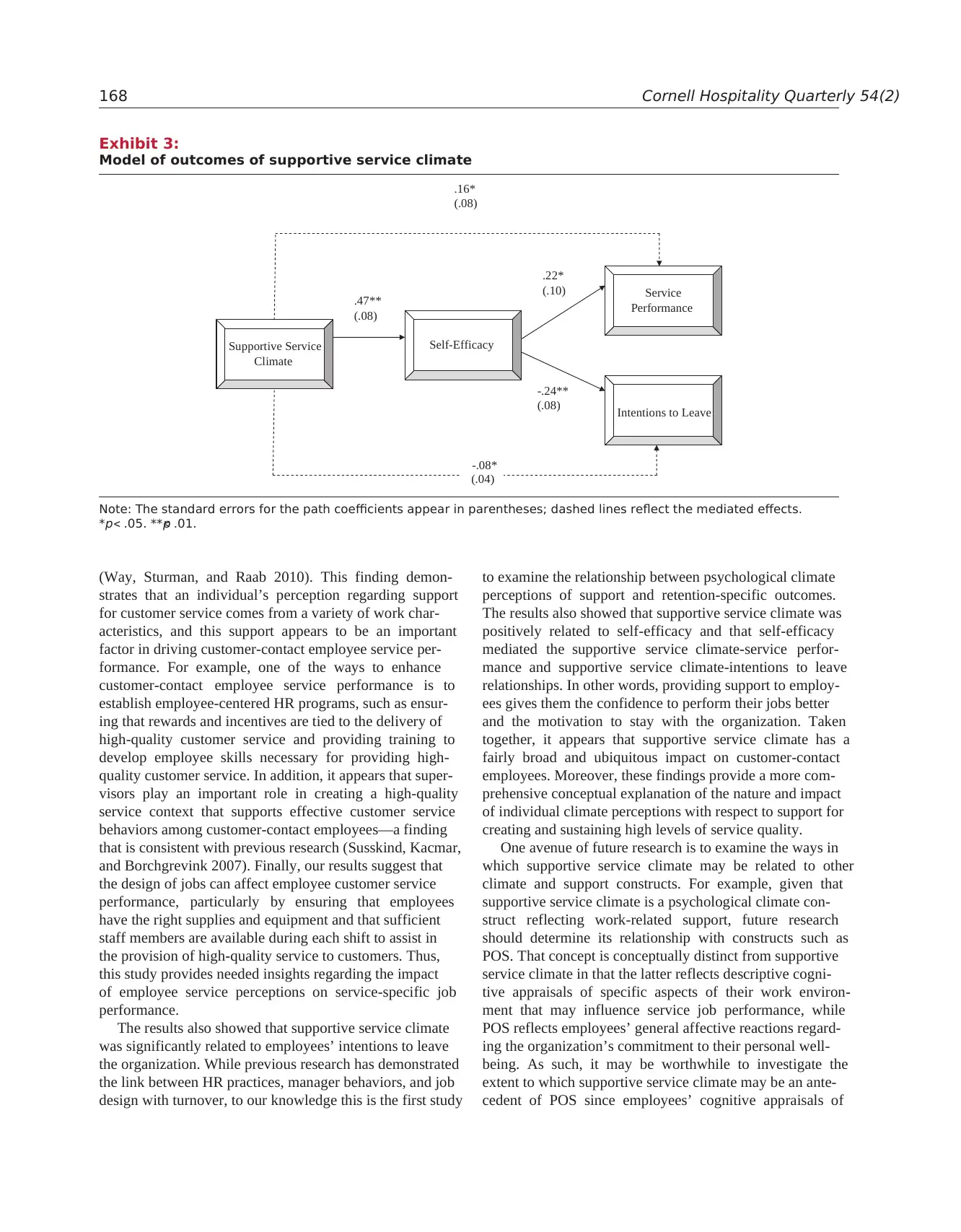

Examination of the statistical analysis presented in Exhibit 2

suggests that supportive service climate was significantly

related to service performance (r=.23, p < .01) and intentions

to leave (r=–.38, p < .01), demonstrating support for hypoth-

eses 1 and 2. To test the mediated relationships, we estimated

the model presented in Figure 1 using Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and

Muthén 2007) with the covariance matrix as input and a

maximum likelihood solution. In the structural model, sup-

portive service climate was the exogenous variable and self-

efficacy, service performance, and intentions to leave were

endogenous variables (see Exhibit 3). Self-efficacy was

presented as a mediator of the relationships between sup-

portive service climate and both customer service perfor-

mance and intentions to leave. We assessed the fit of the

model using (1) the global chi-square test of model fit,

(2) model fit statistics such as CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR,

and (3) the significance of each path in the model.

Overall, the hypothesized model produced a reasonable

fit to the data, χ2(703, N =150) =1119.17, p< .001, CFI=.91,

RMSEA =.06, and SRMR =.09. As depicted in Exhibit 3,

all of the hypothesized path coefficients were statistically

significant, thereby providing additional support for the

model. To determine whether the hypothesized model is

the best approximation to the data, two alternative models

were tested. Alternative model 1 assessed whether the rela-

tionship between supportive service climate and service

performance was partially mediated by self-efficacy, and

alternative model 2 assessed whether the relationship

between supportive service climate and intentions to leave

was partially mediated by self-efficacy.3 While the fit statis-

tics for both alternative models were within the conven-

tional values, some of the paths became nonsignificant with

the inclusions of the partially mediated paths. As such, the

hypothesized model provided the best fit to the data.

Although not hypothesized, we found a significant rela-

tionship (see Exhibit 2) between intentions to leave and cus-

tomer service job performance (r = –.22, p < .01). This

relationship may suggest that customer-contact employees

who had greater success serving customers were ultimately

happier because of their positive interactions with custom-

ers and more likely to stay in their jobs than were employ-

ees who had less success serving customers.4

Discussion

One of the key findings from this study was the signifi-

cant relationship between supportive service climate and

supervisor ratings of customer service job performance

Exhibit 2:

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1. Shift 1.22 0.42 —

2. Gender 1.49 0.50 –.16* —

3. Age 33.28 14.36 –.23** .03 —

4. Education 2.47 1.03 .02 –.15 .00 —

5. Organizational tenure101.02 112.05 –.22** .02 .58** .02 —

6. Service climate 4.91 1.21 –.14 .15 .03 –.17* –.10 —

7. Self-efficacy 6.05 1.04 –.15 .19* .03 .13 –.03 .29** —

8. Intentions to leave 2.33 1.67 .25** –.20 –.36** .12 –.23** –.38** –.26** —

9. Service performance 5.24 1.19 –.17* .03 .03 –.09 .11 .23** .16* –.22** —

Note: N= 150. Means and standard deviations are reported on the basis of a 7-point scale. Means and standard deviations for time employe

organization are represented in months. Service performance and supportive service climate represent multidimensional constructs.

*p < .05. **p< .01.

climate was best reflected at the individual or unit level of