Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products

Added on 2023-05-30

19 Pages20147 Words490 Views

Research Article

Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values

and responses to environmentally friendly products☆

Kelly L. Haws a,⁎, Karen Page Winterich b , Rebecca Walker Naylor c

a Owen Graduate School of Management, 401 21st Ave South, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203, USA

b Smeal College of Business, Pennsylvania State University, 449 Business Building, University Park, PA, 16802, USA

c Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 2100 Neil Avenue, 538 Fisher Hall, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Received 30 October 2012; received in revised form 23 October 2013; accepted 4 November 2013

Available online 13 November 2013

Abstract

The primary goal of this research is to conceptualize and develop a scale of green consumption values, which we define as the tendency to

express the value of environmental protection through one's purchases and consumption behaviors. Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-

item measure we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to capture green consumption values in a reliable, valid, and parsimonious manner.

We further theorize and empirically demonstrate that green consumption values are part of a larger nomological network associated with

conservation of not just environmental resources but also personal financial and physical resources. Finally, we demonstrate that the GREEN scale

predicts consumer preference for environmentally friendly products. In doing so, we demonstrate that stronger green consumption values increase

preference for environmentally friendly products through more favorable evaluations of the non-environmental attributes of these products. These

results have important implications for consumer responses to the growing number of environmentally friendly products.

© 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Sustainability; Scale development; Environmental marketing; Green marketing; Motivated reasoning

1. Introduction

In today's marketplace, consumers are increasingly faced

with choices between “green” products and their more

traditional counterparts, as more firms produce products

whose composition and/or packaging are positioned as

environmentally friendly. For example, Wal-Mart is pressuring

its suppliers like General Electric and Procter & Gamble to

provide environmentally friendly products (Rosenbloom &

Barbaro, 2009). Moreover, many corporate initiatives now

focus exclusively on environmental issues, such as KPMG's

Global Green Initiative (KPMG, 2010; see also Menon &

Menon, 1997). However, the extent to which consumers value

and therefore positively respond to such offerings through

value-consistent behavior remains questionable.

Clearly not all consumers are willing to buy environmentally

friendly (EF) products. 1 Some consumers may be reluctant to

purchase EF products because they are perceived to be less

effective (Luchs et al., 2010). Cost may also be a critical

☆ The authors gratefully acknowledge that this project was funded by the Alton M.

& Marion R. Withers Retailing Research Grant Center for Retailing Studies, Texas

A&M University. The first two authors contributed equally to this research.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: Kelly.haws@vanderbilt.edu (K.L. Haws),

kpw2@psu.edu (K.P. Winterich), naylor_53@fisher.osu.edu (R.W. Naylor).

1 We define an environmentally friendly product as one with at least one positive

environmental attribute. An “environmental attribute” is an attribute that reflects the

impact of the product on the environment. As such, environmental product attributes

can be positive (i.e., the product has little to no negative impact on the environment

and is considered environmentally friendly) or negative (i.e., the product harms the

environment). This definition is consistent with the definition of “ethical attributes”

used in past research (Irwin & Naylor, 2009; Luchs, Naylor, Irwin, & Raghunathan,

2010; Peloza, White, & Shang, 2013), with the key distinction being that

environmental attributes are specifically about the environment, not more broadly

about any issue that a consumer sees as relevant to their values/ethics (e.g., child

labor concerns; unsafe work environments, donations to charity, discrimination;

Mohr & Webb, 2005).

1057-7408/$ -see front matter © 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336 – 354

Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values

and responses to environmentally friendly products☆

Kelly L. Haws a,⁎, Karen Page Winterich b , Rebecca Walker Naylor c

a Owen Graduate School of Management, 401 21st Ave South, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37203, USA

b Smeal College of Business, Pennsylvania State University, 449 Business Building, University Park, PA, 16802, USA

c Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 2100 Neil Avenue, 538 Fisher Hall, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Received 30 October 2012; received in revised form 23 October 2013; accepted 4 November 2013

Available online 13 November 2013

Abstract

The primary goal of this research is to conceptualize and develop a scale of green consumption values, which we define as the tendency to

express the value of environmental protection through one's purchases and consumption behaviors. Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-

item measure we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to capture green consumption values in a reliable, valid, and parsimonious manner.

We further theorize and empirically demonstrate that green consumption values are part of a larger nomological network associated with

conservation of not just environmental resources but also personal financial and physical resources. Finally, we demonstrate that the GREEN scale

predicts consumer preference for environmentally friendly products. In doing so, we demonstrate that stronger green consumption values increase

preference for environmentally friendly products through more favorable evaluations of the non-environmental attributes of these products. These

results have important implications for consumer responses to the growing number of environmentally friendly products.

© 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Sustainability; Scale development; Environmental marketing; Green marketing; Motivated reasoning

1. Introduction

In today's marketplace, consumers are increasingly faced

with choices between “green” products and their more

traditional counterparts, as more firms produce products

whose composition and/or packaging are positioned as

environmentally friendly. For example, Wal-Mart is pressuring

its suppliers like General Electric and Procter & Gamble to

provide environmentally friendly products (Rosenbloom &

Barbaro, 2009). Moreover, many corporate initiatives now

focus exclusively on environmental issues, such as KPMG's

Global Green Initiative (KPMG, 2010; see also Menon &

Menon, 1997). However, the extent to which consumers value

and therefore positively respond to such offerings through

value-consistent behavior remains questionable.

Clearly not all consumers are willing to buy environmentally

friendly (EF) products. 1 Some consumers may be reluctant to

purchase EF products because they are perceived to be less

effective (Luchs et al., 2010). Cost may also be a critical

☆ The authors gratefully acknowledge that this project was funded by the Alton M.

& Marion R. Withers Retailing Research Grant Center for Retailing Studies, Texas

A&M University. The first two authors contributed equally to this research.

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: Kelly.haws@vanderbilt.edu (K.L. Haws),

kpw2@psu.edu (K.P. Winterich), naylor_53@fisher.osu.edu (R.W. Naylor).

1 We define an environmentally friendly product as one with at least one positive

environmental attribute. An “environmental attribute” is an attribute that reflects the

impact of the product on the environment. As such, environmental product attributes

can be positive (i.e., the product has little to no negative impact on the environment

and is considered environmentally friendly) or negative (i.e., the product harms the

environment). This definition is consistent with the definition of “ethical attributes”

used in past research (Irwin & Naylor, 2009; Luchs, Naylor, Irwin, & Raghunathan,

2010; Peloza, White, & Shang, 2013), with the key distinction being that

environmental attributes are specifically about the environment, not more broadly

about any issue that a consumer sees as relevant to their values/ethics (e.g., child

labor concerns; unsafe work environments, donations to charity, discrimination;

Mohr & Webb, 2005).

1057-7408/$ -see front matter © 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.11.002

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336 – 354

deterrent; eco-friendly products have historically cost more than

their traditional 2 counterparts (Dale, 2008; Mintel, 2009), and not

all consumers are willing to pay price premiums for ethical or EF

products (Mintel, 2010). Clearly, some consumers are willing to

purchase EF products while others are not, which suggests that

there are individual differences among consumers in the value

they place on conserving the environment in consumption

settings. Therefore, the primary objective of our research is to

develop a method to understand differences across consumers

who do and do not value conserving the environment as part of

their consumption behavior. As such, we introduce the construct

of green consumption values, which we formally define as the

tendency to express the value of environmental protection

through one's purchases and consumption behaviors.

Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-item measure

we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to reliably

capture green consumption values. We further suggest that

green consumption values are part of a larger nomological

network associated with conservation of not just environmental

resources but also personal financial and physical resources. In

others words, consumers with stronger green consumption

values (i.e., “green” consumers) are generally oriented toward

protecting resources at both the environmental and personal

level. We test these proposed nomological network relation-

ships empirically as part of our larger scale development effort.

Finally, to further validate the scale, we demonstrate that the

GREEN scale predicts consumer preference for EF products. In

doing so, we show that stronger green consumption values

increase preference for EF products through more favorable

evaluations of these products' non-environmental attributes,

consistent with consumers' use of motivated reasoning in other

decision making contexts (Kunda, 1990).

2. Understanding green consumers

Environmentally responsible behavior is receiving increasing

attention in the literature (Catlin & Wang, 2013; Leonidou,

Katsikeas, & Morgan, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; Trudel & Argo,

2013; White & Simpson, 2013). This focus is consistent with a

broader interest in understanding socially responsible consumption

that has persisted for several decades (e.g., Anderson &

Cunningham, 1972; Antil, 1984; Roberts, 1995; Webb, Mohr, &

Harris, 2008; Webster, 1975). However, the extent to which

consumers' environmentally responsible behaviors differ among

individuals, and why, is not clear given that existing research has

focused on responses to environmental products at the firm level

(Leonidou et al., 2013) or as a result of differing situational factors

(Catlin & Wang, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; White & Simpson,

2013). To be sure, past research aimed at understanding socially

responsible consumption has sought to understand differences

among individual consumers. Yet, this research focused on broader

social issues, as illustrated by Roberts' (1993) description of a

socially responsible consumer as “one who purchases products and

services perceived to have a positive (or less negative) influence on

the environment or who patronizes businesses that attempt to effect

related positive social change” (p. 140).

Although we acknowledge that environmental issues have

often been conceptualized as part of a broader effort to understand

socially conscious consumers (Mohr, Webb, & Harris, 2001;

Roberts, 1993; Webster, 1975), the more general notion of

socially responsible consumption is multifaceted. As such,

investigations of socially conscious consumption have often led

to long and complex measures designed to capture the full scope

of the constructs involved, which include issues not directly

related to the environment (see, for example, Antil, 1984; Webb

et al., 2008). Other scales designed to measure consumer social

responsibility have become dated as perceptions of socially

responsible behaviors change over time (Dunlap, Van Liere,

Mertig, & Jones, 2000).3 Thus, our primary goal is to develop a

concise measure of exclusively green consumption values, as

opposed to broader attitudes toward socially responsible behavior

or environmental consciousness. As we develop this measure, we

also seek to identify the consumer characteristics associated with

green consumption values as part of a broader nomological

network and understanding of the green consumer. In addition to

the desire of consumers with strong green consumption values to

use society's environmental resources wisely (i.e., clean water,

clean air, flora, and fauna; Cunningham, Cunningham, &

Woodworth, 2001), we suggest that green consumers also value

conservation of their personal resources.

As such, we focus our conceptualization and nomological

network of green consumption values on the underlying

characteristics of concern for both individual-level financial and

physical resources. Specifically, we expect consumers with

stronger green consumption values to be more conscientious in

the use of their financial resources, consistent with past research

suggesting that green consumption (or conservation) may be

related to concerns about spending money. For example, in one

study, price consciousness was the only variable, other than

household characteristics (i.e., number of rooms) and family size,

to significantly predict energy use (Heslop, Moran, & Cousineau,

1981). In another study, care in shopping (reflecting shopping for

specials and checking prices) significantly predicted making a

special effort to buy environmentally-friendly products for both

men and women (Shrum, McCarty, & Lowrey, 1995).

Relatedly, we also expect consumers with stronger green

consumption values to be more careful users of physical

resources, for example by using their products fully and by not

using more than the necessary amount of a product for it to

perform its function effectively, as suggested by Lastovicka,

Bettencourt, Hughner, and Kuntze's (1999) work on frugal

consumption. Specifically, we suggest that green consumers

will be reluctant to give up their physical possessions because

they will seek to extract full and complete value from goods

2 When we refer to a “traditional” product, we refer to offerings in which there

is no known environmentally friendly attribute, though they are not necessarily

harmful to the environment.

3 For example, some scale items use figures that become dated (e.g., “I would

be willing to accept an increase in my family's total expenses of $120 next year

to promote the wise use of natural resources” from Antil, 1984), while others

focus on avoiding trade with certain countries due to policies that have changed

over time (e.g., “I do not buy products from companies that have investments in

South Africa” from Roberts, 1995).

337K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

their traditional 2 counterparts (Dale, 2008; Mintel, 2009), and not

all consumers are willing to pay price premiums for ethical or EF

products (Mintel, 2010). Clearly, some consumers are willing to

purchase EF products while others are not, which suggests that

there are individual differences among consumers in the value

they place on conserving the environment in consumption

settings. Therefore, the primary objective of our research is to

develop a method to understand differences across consumers

who do and do not value conserving the environment as part of

their consumption behavior. As such, we introduce the construct

of green consumption values, which we formally define as the

tendency to express the value of environmental protection

through one's purchases and consumption behaviors.

Across six studies, we demonstrate that the six-item measure

we develop (i.e., the GREEN scale) can be used to reliably

capture green consumption values. We further suggest that

green consumption values are part of a larger nomological

network associated with conservation of not just environmental

resources but also personal financial and physical resources. In

others words, consumers with stronger green consumption

values (i.e., “green” consumers) are generally oriented toward

protecting resources at both the environmental and personal

level. We test these proposed nomological network relation-

ships empirically as part of our larger scale development effort.

Finally, to further validate the scale, we demonstrate that the

GREEN scale predicts consumer preference for EF products. In

doing so, we show that stronger green consumption values

increase preference for EF products through more favorable

evaluations of these products' non-environmental attributes,

consistent with consumers' use of motivated reasoning in other

decision making contexts (Kunda, 1990).

2. Understanding green consumers

Environmentally responsible behavior is receiving increasing

attention in the literature (Catlin & Wang, 2013; Leonidou,

Katsikeas, & Morgan, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; Trudel & Argo,

2013; White & Simpson, 2013). This focus is consistent with a

broader interest in understanding socially responsible consumption

that has persisted for several decades (e.g., Anderson &

Cunningham, 1972; Antil, 1984; Roberts, 1995; Webb, Mohr, &

Harris, 2008; Webster, 1975). However, the extent to which

consumers' environmentally responsible behaviors differ among

individuals, and why, is not clear given that existing research has

focused on responses to environmental products at the firm level

(Leonidou et al., 2013) or as a result of differing situational factors

(Catlin & Wang, 2013; Peloza et al., 2013; White & Simpson,

2013). To be sure, past research aimed at understanding socially

responsible consumption has sought to understand differences

among individual consumers. Yet, this research focused on broader

social issues, as illustrated by Roberts' (1993) description of a

socially responsible consumer as “one who purchases products and

services perceived to have a positive (or less negative) influence on

the environment or who patronizes businesses that attempt to effect

related positive social change” (p. 140).

Although we acknowledge that environmental issues have

often been conceptualized as part of a broader effort to understand

socially conscious consumers (Mohr, Webb, & Harris, 2001;

Roberts, 1993; Webster, 1975), the more general notion of

socially responsible consumption is multifaceted. As such,

investigations of socially conscious consumption have often led

to long and complex measures designed to capture the full scope

of the constructs involved, which include issues not directly

related to the environment (see, for example, Antil, 1984; Webb

et al., 2008). Other scales designed to measure consumer social

responsibility have become dated as perceptions of socially

responsible behaviors change over time (Dunlap, Van Liere,

Mertig, & Jones, 2000).3 Thus, our primary goal is to develop a

concise measure of exclusively green consumption values, as

opposed to broader attitudes toward socially responsible behavior

or environmental consciousness. As we develop this measure, we

also seek to identify the consumer characteristics associated with

green consumption values as part of a broader nomological

network and understanding of the green consumer. In addition to

the desire of consumers with strong green consumption values to

use society's environmental resources wisely (i.e., clean water,

clean air, flora, and fauna; Cunningham, Cunningham, &

Woodworth, 2001), we suggest that green consumers also value

conservation of their personal resources.

As such, we focus our conceptualization and nomological

network of green consumption values on the underlying

characteristics of concern for both individual-level financial and

physical resources. Specifically, we expect consumers with

stronger green consumption values to be more conscientious in

the use of their financial resources, consistent with past research

suggesting that green consumption (or conservation) may be

related to concerns about spending money. For example, in one

study, price consciousness was the only variable, other than

household characteristics (i.e., number of rooms) and family size,

to significantly predict energy use (Heslop, Moran, & Cousineau,

1981). In another study, care in shopping (reflecting shopping for

specials and checking prices) significantly predicted making a

special effort to buy environmentally-friendly products for both

men and women (Shrum, McCarty, & Lowrey, 1995).

Relatedly, we also expect consumers with stronger green

consumption values to be more careful users of physical

resources, for example by using their products fully and by not

using more than the necessary amount of a product for it to

perform its function effectively, as suggested by Lastovicka,

Bettencourt, Hughner, and Kuntze's (1999) work on frugal

consumption. Specifically, we suggest that green consumers

will be reluctant to give up their physical possessions because

they will seek to extract full and complete value from goods

2 When we refer to a “traditional” product, we refer to offerings in which there

is no known environmentally friendly attribute, though they are not necessarily

harmful to the environment.

3 For example, some scale items use figures that become dated (e.g., “I would

be willing to accept an increase in my family's total expenses of $120 next year

to promote the wise use of natural resources” from Antil, 1984), while others

focus on avoiding trade with certain countries due to policies that have changed

over time (e.g., “I do not buy products from companies that have investments in

South Africa” from Roberts, 1995).

337K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

before discarding them, consistent with Haws, Naylor, Coulter,

and Bearden's (2012) work on product retention tendency.

Additionally, we theorize that green consumers will be more

likely to be innovative users of existing physical resources, that

is, that they will creatively reuse and find multiple uses for their

products, as suggested by Price and Ridgeway's (1983) work

on use innovativeness, a behavior indicative of self-recycling.

To understand consumers' green consumption values, the

corresponding nomological net, and their predictive validity, we

first conduct a series of four scale development and validation

studies. In Study 1a, we discuss our development of a six-item

scale to measure green consumption values, compare it to an

existing measure of socially responsible consumption, and

establish a nomological network including concern for both

personal financial and physical resources. Study 1b provides

further validation of the scale and nomological network using an

adult sample. Study 1c demonstrates the test–retest reliability of

the scale while also providing evidence of predictive validity

relative to existing measures of environmental attitudes drawn

from the literature. Study 1d provides further support for the

predictive validity of our green measure with actual choice.

3. Study 1a: Developing the GREEN scale and testing the

nomological network

3.1. Participants and method

To develop the GREEN scale, we initially compiled a list of

58 items intended to measure how much consumers valued the

environment when making consumption decisions. These items

were generated by the authors by adapting items from existing

environmental attitude scales and drawing upon popular press

articles regarding green marketing (e.g., Dale, 2008; Stone,

2009). We presented this set of items, plus other measures

described below, to 264 undergraduate students who were

participating in a multi-phased study for course credit. Given

our intention to parsimoniously assess the tendency to express

the importance of environmental protection through one's

purchases and consumption behaviors, we anticipated a

one-factor model for our GREEN scale.

In addition to the 58 proposed items to assess green

consumption values, we also included the 40-item measure of

Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior (SRCB) devel-

oped by Antil in 1984. Our intent was not to compare our

measure against every existing measure of environmental or

socially responsible values, attitudes, and behaviors, but rather

to develop a concise scale that would not easily become

outdated and would compare well with past measures. We used

the Antil (1984) scale for these benchmarking purposes because

of its inclusion of environmental values as a key part of socially

responsible consumption as well as its existing use in the

literature. We anticipated that our six-item measure would be

strongly related to this existing 40-item measure.

Additionally, we sought to examine our proposed nomolog-

ical network with respect to the relationship between green

consumption values and existing measures of consumers' use of

personal financial and physical resources. The first of these

measures was Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality scale.

Lastovicka et al. (1999) characterized frugality as being about

both the careful acquisition and careful consumption of goods,

encompassing the vigilant use of both financial and physical

resources. Therefore, we expect GREEN to be related to frugality

because of the emphasis a frugal consumer places on the careful

use of financial resources in acquiring goods and concern for

physical possessions during consumption (Lastovicka et al.,

1999). We also measured consumer spending self-control

(CSSC) because we expect greener consumers to exercise more

thoughtfulness and control in their spending decision making,

which would be implied in a positive relationship between

GREEN and CSSC (Haws, Bearden, & Nenkov, 2012). We

also included Lichtenstein, Netemeyer, and Burton's (1990)

measure of price consciousness and Lichtenstein, Ridgway, and

Netemeyer's (1993) measure of value consciousness. We expect

GREEN to be positively related to both of these constructs as

these tendencies also suggest careful use of financial resources.

To address the conservative use of personal physical resources

beyond that captured in Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality scale,

we measured the tendency to retain or relinquish possessions

(using the product retention tendency scale; Haws, Naylor et al.,

2012) and innovativeness in the use and reuse of products (using

Price & Ridgeway's, 1983 three-dimensional use innovativeness

scale). We expect these constructs to be positively related to

GREEN, as they involve a focus on the careful disposition and

use of physical resources.

Finally, to assess the potential for consumers to misrepresent

themselves by responding in a socially desirable manner, which

may be of particular concern for socially responsible and

environmentally friendly behaviors (Luchs et al., 2010), we

assessed the relationship between GREEN and both self-

deceptive enhancement and impression management using a

shortened version of Paulhus (1998) Balanced Inventory of

Desirable Responding (BIDR) scale.

3.2. Results

We first conducted a series of factor analyses to reduce the

set of 58 items. An initial exploratory factor analysis revealed

that there was one primary factor that emerged from the set of

58 items, with an eigenvalue of 19.23 for the first factor versus

5.00 for the second factor, which explained 33% versus 9% of

variance, respectively. A careful inspection of the factor

loadings for the second and subsequent factors showed that

the loadings were significantly smaller than the loadings on the

first factor, supporting the proposed one-factor model as

sufficiently capturing our construct. 4 As such, we focused on

identifying items from this one factor that would assess green

consumption values.

We found that 10 items had a loading of at least .70 or higher on

the first factor. We carefully examined these 10 items to limit the

use of redundant or unclear items in order to use as few items as

4 We also compared the one-factor model to a series of other models

including two, three, and four factor models, and we consistently found

evidence that one factor provided the best fitting model.

338 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

and Bearden's (2012) work on product retention tendency.

Additionally, we theorize that green consumers will be more

likely to be innovative users of existing physical resources, that

is, that they will creatively reuse and find multiple uses for their

products, as suggested by Price and Ridgeway's (1983) work

on use innovativeness, a behavior indicative of self-recycling.

To understand consumers' green consumption values, the

corresponding nomological net, and their predictive validity, we

first conduct a series of four scale development and validation

studies. In Study 1a, we discuss our development of a six-item

scale to measure green consumption values, compare it to an

existing measure of socially responsible consumption, and

establish a nomological network including concern for both

personal financial and physical resources. Study 1b provides

further validation of the scale and nomological network using an

adult sample. Study 1c demonstrates the test–retest reliability of

the scale while also providing evidence of predictive validity

relative to existing measures of environmental attitudes drawn

from the literature. Study 1d provides further support for the

predictive validity of our green measure with actual choice.

3. Study 1a: Developing the GREEN scale and testing the

nomological network

3.1. Participants and method

To develop the GREEN scale, we initially compiled a list of

58 items intended to measure how much consumers valued the

environment when making consumption decisions. These items

were generated by the authors by adapting items from existing

environmental attitude scales and drawing upon popular press

articles regarding green marketing (e.g., Dale, 2008; Stone,

2009). We presented this set of items, plus other measures

described below, to 264 undergraduate students who were

participating in a multi-phased study for course credit. Given

our intention to parsimoniously assess the tendency to express

the importance of environmental protection through one's

purchases and consumption behaviors, we anticipated a

one-factor model for our GREEN scale.

In addition to the 58 proposed items to assess green

consumption values, we also included the 40-item measure of

Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior (SRCB) devel-

oped by Antil in 1984. Our intent was not to compare our

measure against every existing measure of environmental or

socially responsible values, attitudes, and behaviors, but rather

to develop a concise scale that would not easily become

outdated and would compare well with past measures. We used

the Antil (1984) scale for these benchmarking purposes because

of its inclusion of environmental values as a key part of socially

responsible consumption as well as its existing use in the

literature. We anticipated that our six-item measure would be

strongly related to this existing 40-item measure.

Additionally, we sought to examine our proposed nomolog-

ical network with respect to the relationship between green

consumption values and existing measures of consumers' use of

personal financial and physical resources. The first of these

measures was Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality scale.

Lastovicka et al. (1999) characterized frugality as being about

both the careful acquisition and careful consumption of goods,

encompassing the vigilant use of both financial and physical

resources. Therefore, we expect GREEN to be related to frugality

because of the emphasis a frugal consumer places on the careful

use of financial resources in acquiring goods and concern for

physical possessions during consumption (Lastovicka et al.,

1999). We also measured consumer spending self-control

(CSSC) because we expect greener consumers to exercise more

thoughtfulness and control in their spending decision making,

which would be implied in a positive relationship between

GREEN and CSSC (Haws, Bearden, & Nenkov, 2012). We

also included Lichtenstein, Netemeyer, and Burton's (1990)

measure of price consciousness and Lichtenstein, Ridgway, and

Netemeyer's (1993) measure of value consciousness. We expect

GREEN to be positively related to both of these constructs as

these tendencies also suggest careful use of financial resources.

To address the conservative use of personal physical resources

beyond that captured in Lastovicka et al.'s (1999) frugality scale,

we measured the tendency to retain or relinquish possessions

(using the product retention tendency scale; Haws, Naylor et al.,

2012) and innovativeness in the use and reuse of products (using

Price & Ridgeway's, 1983 three-dimensional use innovativeness

scale). We expect these constructs to be positively related to

GREEN, as they involve a focus on the careful disposition and

use of physical resources.

Finally, to assess the potential for consumers to misrepresent

themselves by responding in a socially desirable manner, which

may be of particular concern for socially responsible and

environmentally friendly behaviors (Luchs et al., 2010), we

assessed the relationship between GREEN and both self-

deceptive enhancement and impression management using a

shortened version of Paulhus (1998) Balanced Inventory of

Desirable Responding (BIDR) scale.

3.2. Results

We first conducted a series of factor analyses to reduce the

set of 58 items. An initial exploratory factor analysis revealed

that there was one primary factor that emerged from the set of

58 items, with an eigenvalue of 19.23 for the first factor versus

5.00 for the second factor, which explained 33% versus 9% of

variance, respectively. A careful inspection of the factor

loadings for the second and subsequent factors showed that

the loadings were significantly smaller than the loadings on the

first factor, supporting the proposed one-factor model as

sufficiently capturing our construct. 4 As such, we focused on

identifying items from this one factor that would assess green

consumption values.

We found that 10 items had a loading of at least .70 or higher on

the first factor. We carefully examined these 10 items to limit the

use of redundant or unclear items in order to use as few items as

4 We also compared the one-factor model to a series of other models

including two, three, and four factor models, and we consistently found

evidence that one factor provided the best fitting model.

338 K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

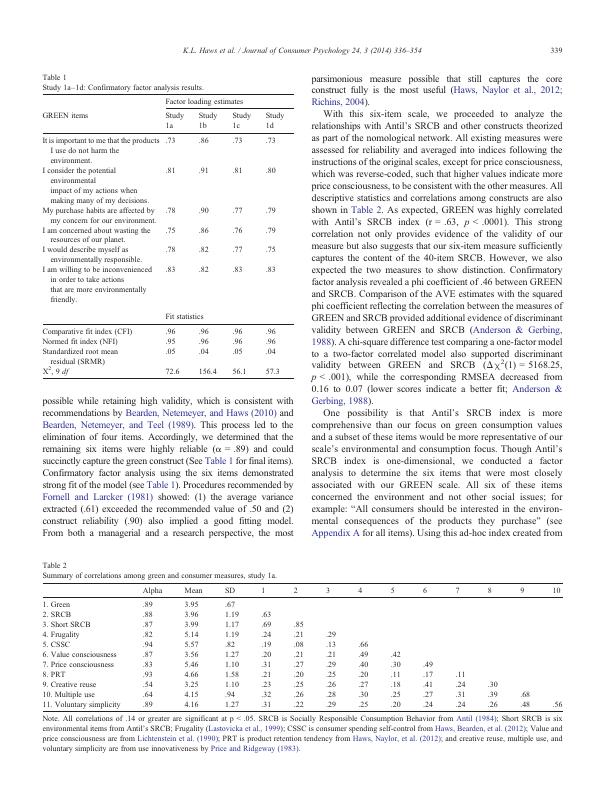

possible while retaining high validity, which is consistent with

recommendations by Bearden, Netemeyer, and Haws (2010) and

Bearden, Netemeyer, and Teel (1989). This process led to the

elimination of four items. Accordingly, we determined that the

remaining six items were highly reliable (α = .89) and could

succinctly capture the green construct (See Table 1 for final items).

Confirmatory factor analysis using the six items demonstrated

strong fit of the model (see Table 1). Procedures recommended by

Fornell and Larcker (1981) showed: (1) the average variance

extracted (.61) exceeded the recommended value of .50 and (2)

construct reliability (.90) also implied a good fitting model.

From both a managerial and a research perspective, the most

parsimonious measure possible that still captures the core

construct fully is the most useful (Haws, Naylor et al., 2012;

Richins, 2004).

With this six-item scale, we proceeded to analyze the

relationships with Antil's SRCB and other constructs theorized

as part of the nomological network. All existing measures were

assessed for reliability and averaged into indices following the

instructions of the original scales, except for price consciousness,

which was reverse-coded, such that higher values indicate more

price consciousness, to be consistent with the other measures. All

descriptive statistics and correlations among constructs are also

shown in Table 2. As expected, GREEN was highly correlated

with Antil's SRCB index (r = .63, p b .0001). This strong

correlation not only provides evidence of the validity of our

measure but also suggests that our six-item measure sufficiently

captures the content of the 40-item SRCB. However, we also

expected the two measures to show distinction. Confirmatory

factor analysis revealed a phi coefficient of .46 between GREEN

and SRCB. Comparison of the AVE estimates with the squared

phi coefficient reflecting the correlation between the measures of

GREEN and SRCB provided additional evidence of discriminant

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988). A chi-square difference test comparing a one-factor model

to a two-factor correlated model also supported discriminant

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Δχ2 (1) = 5168.25,

p b .001), while the corresponding RMSEA decreased from

0.16 to 0.07 (lower scores indicate a better fit; Anderson &

Gerbing, 1988).

One possibility is that Antil's SRCB index is more

comprehensive than our focus on green consumption values

and a subset of these items would be more representative of our

scale's environmental and consumption focus. Though Antil's

SRCB index is one-dimensional, we conducted a factor

analysis to determine the six items that were most closely

associated with our GREEN scale. All six of these items

concerned the environment and not other social issues; for

example: “All consumers should be interested in the environ-

mental consequences of the products they purchase” (see

Appendix A for all items). Using this ad-hoc index created from

Table 1

Study 1a–1d: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Factor loading estimates

GREEN items Study

1a

Study

1b

Study

1c

Study

1d

It is important to me that the products

I use do not harm the

environment.

.73 .86 .73 .73

I consider the potential

environmental

impact of my actions when

making many of my decisions.

.81 .91 .81 .80

My purchase habits are affected by

my concern for our environment.

.78 .90 .77 .79

I am concerned about wasting the

resources of our planet.

.75 .86 .76 .79

I would describe myself as

environmentally responsible.

.78 .82 .77 .75

I am willing to be inconvenienced

in order to take actions

that are more environmentally

friendly.

.83 .82 .83 .83

Fit statistics

Comparative fit index (CFI) .96 .96 .96 .96

Normed fit index (NFI) .95 .96 .96 .96

Standardized root mean

residual (SRMR)

.05 .04 .05 .04

Χ2 , 9 df 72.6 156.4 56.1 57.3

Table 2

Summary of correlations among green and consumer measures, study 1a.

Alpha Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. Green .89 3.95 .67

2. SRCB .88 3.96 1.19 .63

3. Short SRCB .87 3.99 1.17 .69 .85

4. Frugality .82 5.14 1.19 .24 .21 .29

5. CSSC .94 5.57 .82 .19 .08 .13 .66

6. Value consciousness .87 3.56 1.27 .20 .21 .21 .49 .42

7. Price consciousness .83 5.46 1.10 .31 .27 .29 .40 .30 .49

8. PRT .93 4.66 1.58 .21 .20 .25 .20 .11 .17 .11

9. Creative reuse .54 3.25 1.10 .23 .25 .26 .27 .18 .41 .24 .30

10. Multiple use .64 4.15 .94 .32 .26 .28 .30 .25 .27 .31 .39 .68

11. Voluntary simplicity .89 4.16 1.27 .31 .22 .29 .25 .20 .24 .24 .26 .48 .56

Note. All correlations of .14 or greater are significant at p b .05. SRCB is Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior from Antil (1984); Short SRCB is six

environmental items from Antil's SRCB; Frugality (Lastovicka et al., 1999); CSSC is consumer spending self-control from Haws, Bearden, et al. (2012); Value and

price consciousness are from Lichtenstein et al. (1990); PRT is product retention tendency from Haws, Naylor, et al. (2012); and creative reuse, multiple use, and

voluntary simplicity are from use innovativeness by Price and Ridgeway (1983).

339K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

recommendations by Bearden, Netemeyer, and Haws (2010) and

Bearden, Netemeyer, and Teel (1989). This process led to the

elimination of four items. Accordingly, we determined that the

remaining six items were highly reliable (α = .89) and could

succinctly capture the green construct (See Table 1 for final items).

Confirmatory factor analysis using the six items demonstrated

strong fit of the model (see Table 1). Procedures recommended by

Fornell and Larcker (1981) showed: (1) the average variance

extracted (.61) exceeded the recommended value of .50 and (2)

construct reliability (.90) also implied a good fitting model.

From both a managerial and a research perspective, the most

parsimonious measure possible that still captures the core

construct fully is the most useful (Haws, Naylor et al., 2012;

Richins, 2004).

With this six-item scale, we proceeded to analyze the

relationships with Antil's SRCB and other constructs theorized

as part of the nomological network. All existing measures were

assessed for reliability and averaged into indices following the

instructions of the original scales, except for price consciousness,

which was reverse-coded, such that higher values indicate more

price consciousness, to be consistent with the other measures. All

descriptive statistics and correlations among constructs are also

shown in Table 2. As expected, GREEN was highly correlated

with Antil's SRCB index (r = .63, p b .0001). This strong

correlation not only provides evidence of the validity of our

measure but also suggests that our six-item measure sufficiently

captures the content of the 40-item SRCB. However, we also

expected the two measures to show distinction. Confirmatory

factor analysis revealed a phi coefficient of .46 between GREEN

and SRCB. Comparison of the AVE estimates with the squared

phi coefficient reflecting the correlation between the measures of

GREEN and SRCB provided additional evidence of discriminant

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Anderson & Gerbing,

1988). A chi-square difference test comparing a one-factor model

to a two-factor correlated model also supported discriminant

validity between GREEN and SRCB (Δχ2 (1) = 5168.25,

p b .001), while the corresponding RMSEA decreased from

0.16 to 0.07 (lower scores indicate a better fit; Anderson &

Gerbing, 1988).

One possibility is that Antil's SRCB index is more

comprehensive than our focus on green consumption values

and a subset of these items would be more representative of our

scale's environmental and consumption focus. Though Antil's

SRCB index is one-dimensional, we conducted a factor

analysis to determine the six items that were most closely

associated with our GREEN scale. All six of these items

concerned the environment and not other social issues; for

example: “All consumers should be interested in the environ-

mental consequences of the products they purchase” (see

Appendix A for all items). Using this ad-hoc index created from

Table 1

Study 1a–1d: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Factor loading estimates

GREEN items Study

1a

Study

1b

Study

1c

Study

1d

It is important to me that the products

I use do not harm the

environment.

.73 .86 .73 .73

I consider the potential

environmental

impact of my actions when

making many of my decisions.

.81 .91 .81 .80

My purchase habits are affected by

my concern for our environment.

.78 .90 .77 .79

I am concerned about wasting the

resources of our planet.

.75 .86 .76 .79

I would describe myself as

environmentally responsible.

.78 .82 .77 .75

I am willing to be inconvenienced

in order to take actions

that are more environmentally

friendly.

.83 .82 .83 .83

Fit statistics

Comparative fit index (CFI) .96 .96 .96 .96

Normed fit index (NFI) .95 .96 .96 .96

Standardized root mean

residual (SRMR)

.05 .04 .05 .04

Χ2 , 9 df 72.6 156.4 56.1 57.3

Table 2

Summary of correlations among green and consumer measures, study 1a.

Alpha Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. Green .89 3.95 .67

2. SRCB .88 3.96 1.19 .63

3. Short SRCB .87 3.99 1.17 .69 .85

4. Frugality .82 5.14 1.19 .24 .21 .29

5. CSSC .94 5.57 .82 .19 .08 .13 .66

6. Value consciousness .87 3.56 1.27 .20 .21 .21 .49 .42

7. Price consciousness .83 5.46 1.10 .31 .27 .29 .40 .30 .49

8. PRT .93 4.66 1.58 .21 .20 .25 .20 .11 .17 .11

9. Creative reuse .54 3.25 1.10 .23 .25 .26 .27 .18 .41 .24 .30

10. Multiple use .64 4.15 .94 .32 .26 .28 .30 .25 .27 .31 .39 .68

11. Voluntary simplicity .89 4.16 1.27 .31 .22 .29 .25 .20 .24 .24 .26 .48 .56

Note. All correlations of .14 or greater are significant at p b .05. SRCB is Socially Responsible Consumption Behavior from Antil (1984); Short SRCB is six

environmental items from Antil's SRCB; Frugality (Lastovicka et al., 1999); CSSC is consumer spending self-control from Haws, Bearden, et al. (2012); Value and

price consciousness are from Lichtenstein et al. (1990); PRT is product retention tendency from Haws, Naylor, et al. (2012); and creative reuse, multiple use, and

voluntary simplicity are from use innovativeness by Price and Ridgeway (1983).

339K.L. Haws et al. / Journal of Consumer Psychology 24, 3 (2014) 336–354

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Consumers' perceptions of luxury brands’ CSR initiativeslg...

|11

|14121

|416