Investigating Consumer Perceptions of CSR in the Luxury Industry

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|11

|14121

|416

Literature Review

AI Summary

This paper reviews the impact of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives on consumer perceptions of luxury brands. It challenges the notion that luxury and CSR are incompatible, arguing that consumers react positively to CSR initiatives under certain conditions. The research extends Carroll's four-dimension model of CSR, categorizing initiatives as 'internal' (economic and ethical) and 'external' (legal and philanthropic). Three experiments demonstrate that external CSR initiatives increase consumers' willingness to buy, particularly among those with higher status and conspicuous consumption orientations. The study contributes to the understanding of the luxury/sustainability relationship and the effectiveness of different CSR dimensions in influencing consumer behavior. It also acknowledges the role of institutional environments and national business systems in shaping CSR implementation.

Consumers'perceptions of luxury brands’CSR initiatives: An

investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption

Cesare Amatullia, * , 1

, Matteo De Angelisb

, Daniel Korschunc

, Simona Romanib

a Ionian Department of Mediterranean Legal and Economic Systems: Society,Environment,Culture,University of Bari Aldo Moro,Via Duomo,259,74123

Taranto,Italy

b Department of Business Management,LUISS University Viale Romania,32,00197 Rome,Italy

c LeBow College of Business,Drexel University,3220 Market St,Philadelphia,PA 19104,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 12 January 2018

Received in revised form

3 May 2018

Accepted 14 May 2018

Available online 17 May 2018

Keywords:

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Sustainability

Luxury marketing

Status consumption

Conspicuous consumption

a b s t r a c t

This research challenges the notion that luxury and CSR are incompatible by investigating whether and

under what conditions consumers react positively to different kinds ofCSR initiatives among luxury

companies. Extending Carroll's four-dimension model of CSR, we argue that some CSR initiatives, namely

those in the economic and ethical dimensions, are less noticeable and visible to consumers than those in

the legal and philanthropic dimensions.We categorized the former as “internal” dimensions and the

latter as “external” dimensions as part of a novel classification of Carroll's four CSR dimensions.To test

our hypotheses, we conducted three experiments e one in a laboratory, one online and one in the field e

with a total of 461 respondents.Our results demonstrate that luxury companies'external (compared to

internal) CSR initiatives increase consumers' willingness to buy; this effect is accentuated for consumers

with higher status and conspicuous consumption orientation.

© 2018 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

1. Introduction

Companiesare increasingly embracing sustainable develop-

ment and Corporate SocialResponsibility (hereafter,CSR; Kotler,

2011; Romani et al.,2016),defined as the set of discretionary ac-

tivities “demonstrating the inclusion of social and environmental

concerns in business operations and in interactions with stake-

holders” (Van Marrewijk and Werre,2003,p. 107).One survey of

over 500 experts from all 32 European countries suggests that the

importance of CSR in business will even increase in the next few

years (Kudłak et al.,2018).Notwithstanding the overallupward

trend, competing views about CSR initiatives in different sectors

still persist (e.g., Sweeney and Coughlan, 2008). For instance, Green

Public Procurement has been shown to be much more important in

the ICT and construction sectors than in the retailand clothing

sectors (Kudłak et al., 2018).Meanwhile, CSR initiatives in the

automotive and aerospace sectors are mainly focused on reducing

the purchases ofchemicals from suppliers (Lindsey,2011),and

those in the retailsector mostly involve the reduction of energy

consumption and the use of greener materials for the interiors of

the stores (e.g.,Ramos and Leal,2017).

There is variability in CSR initiatives across different sectors, and

the present research seeks to contribute to our understanding of

the sources of that variability.The present research suggests that

the extent to which CSR initiatives can be successful - or not - under

the perspective of consumers depends on the visibility of the CSR

initiatives undertaken.

More specifically,we examine the role of CSR initiatives in the

context of the luxury industry. Indeed, while the global luxury

market has been characterized by a steady growth in the last

decade (The Boston Consulting Group, 2017), it is also one that has

been particularly pressured to address social issues (Davies et al.,

2012; De Angelis et al.,2017; Janssen et al.,2014; Kapferer and

Michaut-Denizeau,2014).Consequently,luxury market strategies

have begun to systematically include CSR as a key pillar(e.g.,

Cervellon and Shammas, 2013; Winston, 2016).

investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption

Cesare Amatullia, * , 1

, Matteo De Angelisb

, Daniel Korschunc

, Simona Romanib

a Ionian Department of Mediterranean Legal and Economic Systems: Society,Environment,Culture,University of Bari Aldo Moro,Via Duomo,259,74123

Taranto,Italy

b Department of Business Management,LUISS University Viale Romania,32,00197 Rome,Italy

c LeBow College of Business,Drexel University,3220 Market St,Philadelphia,PA 19104,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 12 January 2018

Received in revised form

3 May 2018

Accepted 14 May 2018

Available online 17 May 2018

Keywords:

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Sustainability

Luxury marketing

Status consumption

Conspicuous consumption

a b s t r a c t

This research challenges the notion that luxury and CSR are incompatible by investigating whether and

under what conditions consumers react positively to different kinds ofCSR initiatives among luxury

companies. Extending Carroll's four-dimension model of CSR, we argue that some CSR initiatives, namely

those in the economic and ethical dimensions, are less noticeable and visible to consumers than those in

the legal and philanthropic dimensions.We categorized the former as “internal” dimensions and the

latter as “external” dimensions as part of a novel classification of Carroll's four CSR dimensions.To test

our hypotheses, we conducted three experiments e one in a laboratory, one online and one in the field e

with a total of 461 respondents.Our results demonstrate that luxury companies'external (compared to

internal) CSR initiatives increase consumers' willingness to buy; this effect is accentuated for consumers

with higher status and conspicuous consumption orientation.

© 2018 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

1. Introduction

Companiesare increasingly embracing sustainable develop-

ment and Corporate SocialResponsibility (hereafter,CSR; Kotler,

2011; Romani et al.,2016),defined as the set of discretionary ac-

tivities “demonstrating the inclusion of social and environmental

concerns in business operations and in interactions with stake-

holders” (Van Marrewijk and Werre,2003,p. 107).One survey of

over 500 experts from all 32 European countries suggests that the

importance of CSR in business will even increase in the next few

years (Kudłak et al.,2018).Notwithstanding the overallupward

trend, competing views about CSR initiatives in different sectors

still persist (e.g., Sweeney and Coughlan, 2008). For instance, Green

Public Procurement has been shown to be much more important in

the ICT and construction sectors than in the retailand clothing

sectors (Kudłak et al., 2018).Meanwhile, CSR initiatives in the

automotive and aerospace sectors are mainly focused on reducing

the purchases ofchemicals from suppliers (Lindsey,2011),and

those in the retailsector mostly involve the reduction of energy

consumption and the use of greener materials for the interiors of

the stores (e.g.,Ramos and Leal,2017).

There is variability in CSR initiatives across different sectors, and

the present research seeks to contribute to our understanding of

the sources of that variability.The present research suggests that

the extent to which CSR initiatives can be successful - or not - under

the perspective of consumers depends on the visibility of the CSR

initiatives undertaken.

More specifically,we examine the role of CSR initiatives in the

context of the luxury industry. Indeed, while the global luxury

market has been characterized by a steady growth in the last

decade (The Boston Consulting Group, 2017), it is also one that has

been particularly pressured to address social issues (Davies et al.,

2012; De Angelis et al.,2017; Janssen et al.,2014; Kapferer and

Michaut-Denizeau,2014).Consequently,luxury market strategies

have begun to systematically include CSR as a key pillar(e.g.,

Cervellon and Shammas, 2013; Winston, 2016).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Kering,publish detailed annual reports about their CSR initiatives.

In short, most luxury brands are aware that they can no longer

ignore CSR issues (Cervellon and Shammas,2013; D'Anolfo et al.,

2017; Winston,2016).

It is perhaps surprising, then, that luxury brands' foray into the

CSR space contradicts some findings in the academic literature,

which has often suggested that those efforts could harm brands'

images (e.g., Torelli et al., 2012). Indeed, scholars have emphasized

that some consumers see luxury and CSR as conflicting concepts

(e.g.,Achabou and Dekhili,2013; Davies et al.,2012; Griskevicius

et al.,2010).The result of this contradiction between business re-

ality and some scientific findings about the role of CSR in luxury is

that today's luxury companies seem to lack an understanding of

how to develop and communicate CSR strategies that can appeal to

luxury consumers.Grounding on the belief that CSR can be lever-

aged to enhance consumers'perception of luxury brands,the pre-

sent article tries to answer the following research questions: What

types of CSR initiatives undertaken by luxury companies are more

likely to encounter consumer favor? Might different types of CSR

initiatives be more appealing for different luxury consumer seg-

ments? And if so, how?

We answer these questions by empirically investigating the

differential effectivenessof different types of CSR initiatives,

labelled internal and external based on the degree to which they are

visible to consumers (see Pino et al.,2016).Specifically,extending

the CSR framework proposed by Carroll (1979, 1991),internal CSR

initiatives refer to economic and ethical initiatives,while external

CSR initiatives refer to legal and philanthropic ones.The evidence

in support of our model comes from three experiments conducted

in three distinct settingsdin the laboratory, in the field, and online.

Overall,this research helps to advance current knowledge on the

luxury/sustainability relationship and,more specifically,on the

effectiveness of CSR actions for consumers of luxury goods in some

important ways.First, our study provides a counterpoint to the

great mass ofresearch studies documenting the incompatibility

between luxury and sustainability issues.Indeed,we specifically

analyze CSR in the luxury context and empirically assess the con-

ditions under which CSR initiatives might improve consumers'

luxury brand perceptions. Second, we extend the literature on CSR

by showing that the type of CSR initiative may differentially affect

consumers’brand perceptions and purchasing intentions.Third,

our research is,to the best of our knowledge,the first to connect

different CSR dimensions with perceptions aboutluxury goods.

Specifically, we test whether external CSR initiatives are more likely

to gain higher consumer favor than internalinitiatives,or vice

versa.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section, we

describe the institutional setting and in section three we review the

main theoretical ideas, thereby providing the research hypotheses.

Section four describes the empirical design, while sections five, six

and seven contain the methodology and results of the three

empiricalstudies conducted.Finally,in section eight,we discuss

the theoretical and managerial implications of our work as well as

its limitations and directions for future studies.

2. Institutional background

While companies may be strongly committed to sustainable

development, the opportunity to develop and implement effective

CSR initiatives is often heavily affected by the specific “rules of the

game” (Thelen, 1999) at play in the different countries in which a

company operates (Halkos and Skouloudis, 2016). As stated by Xie

et al.(2017,p. 28),institutions refer to the “regulative,normative,

and cognitive structures that order and constrain human action,

providing stability to social behavior” (see also Xu and Yang, 2010).

More specifically, the institutional environment of a country refers

to the political and socio-economic environment, the bureaucracy,

the codified and non-codified norms of behavior,and the related

historical development ofa country's institutions (see Fifka and

Pobizhan,2014).Previous studies have shown that good institu-

tional environments strengthen the impact of CSR efforts on firms'

customer satisfaction (Xie et al.,2017).Interestingly,the institu-

tional environment of a country can be analyzed through the so-

called “national business systems approach” developed by

Whitley (1992) and used also to study national CSR characteristics

(e.g.,Habisch et al.,2011).As highlighted by Fifka and Pobizhan

(2014,p. 193),the nationalbusiness system of a country can be

mainly identified with “the politicalsystem,the culturalsystem,

the financial system,and the education and labor system.”

Consistent with this view of the institutional environment, past

research has demonstrated that the level of CSR penetration varies

across countries because of the discrepancies in the institutional

efficiency characterizing different countries (Marquis et al.,2007;

Welford, 2004). For instance, contexts characterized by the

Anglo-Saxon institutionalmodel seem to stimulate ethical and

social initiatives developed by companiesto a greater extent

compared to other contexts (Jackson and Apostolakou,2010).

Institutionalbarriers,however,may also depend on the specific

sector in which the company operates.According to Jackson and

Apostolakou (2010,p. 388),“sector-level institutions may be very

important in explaining the diffusion of ‘minimum standards’for

CSR,where firms respond to coercive and normative pressures of

sectoral-levelregulatory standardsor governance mechanisms

operating at the transnational scale”.

While the present research does not focus specifically on the

role of the institutional environments in driving companies'deci-

sion to engage in CSR initiatives, the framework we propose and the

results we show should be interpreted by taking into account the

differences among countries in terms of standards and legal sys-

tems at play. More specifically, when exploring the effectiveness of

CSR initiatives falling into the legal CSR dimension (Carroll, 1979,

1991),we acknowledge that the boundaries ofcompanies’legal

responsibility may be importantly shaped by the institutional

environment characterizing each country and often differentiating

that country from others.

3. Conceptual development

Past research in luxury has traditionally suggested that CSR is

not a prominent factor in luxury consumers' decision-making

(Davies et al., 2012; Griskevicius et al., 2010); one study even

found that CSR could undermine consumers' perceptions about the

quality of luxury goods (Achabou and Dekhili, 2013). Such findings

are grounded on the idea that luxury generally evokes hedonism,

excess, and ostentation (Cristini et al., 2017; De Barnier et al., 2012),

while CSR generally evokes sobriety, moderation and ethics

(Gladwin et al., 1995; Lochard and Murat,2011).Despite the prior

findings,however,there is burgeoning evidence that luxury and

CSR might be compatible after all (e.g., Janssen et al., 2014). Indeed,

a perceived fit between luxury and CSR may lead consumers to hold

positive attitudes towards luxury products when said products

elicit scarcity and ephemerality (Janssen et al.,2014).Consistent

with this, Kapferer (2010) argued that luxury and sustainable

development can converge when “both focus on rarity” (p.41).

Indeed, on the one hand, luxury is about high quality products that

are objectively rare because they employ rare materials and unique

craftsmanship skills. On the other hand, sustainable development is

about preserving natural resources by limiting the excessive use of

materials that can exceed the world's recycling capabilities

(Kapferer,2010).

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287278

In short, most luxury brands are aware that they can no longer

ignore CSR issues (Cervellon and Shammas,2013; D'Anolfo et al.,

2017; Winston,2016).

It is perhaps surprising, then, that luxury brands' foray into the

CSR space contradicts some findings in the academic literature,

which has often suggested that those efforts could harm brands'

images (e.g., Torelli et al., 2012). Indeed, scholars have emphasized

that some consumers see luxury and CSR as conflicting concepts

(e.g.,Achabou and Dekhili,2013; Davies et al.,2012; Griskevicius

et al.,2010).The result of this contradiction between business re-

ality and some scientific findings about the role of CSR in luxury is

that today's luxury companies seem to lack an understanding of

how to develop and communicate CSR strategies that can appeal to

luxury consumers.Grounding on the belief that CSR can be lever-

aged to enhance consumers'perception of luxury brands,the pre-

sent article tries to answer the following research questions: What

types of CSR initiatives undertaken by luxury companies are more

likely to encounter consumer favor? Might different types of CSR

initiatives be more appealing for different luxury consumer seg-

ments? And if so, how?

We answer these questions by empirically investigating the

differential effectivenessof different types of CSR initiatives,

labelled internal and external based on the degree to which they are

visible to consumers (see Pino et al.,2016).Specifically,extending

the CSR framework proposed by Carroll (1979, 1991),internal CSR

initiatives refer to economic and ethical initiatives,while external

CSR initiatives refer to legal and philanthropic ones.The evidence

in support of our model comes from three experiments conducted

in three distinct settingsdin the laboratory, in the field, and online.

Overall,this research helps to advance current knowledge on the

luxury/sustainability relationship and,more specifically,on the

effectiveness of CSR actions for consumers of luxury goods in some

important ways.First, our study provides a counterpoint to the

great mass ofresearch studies documenting the incompatibility

between luxury and sustainability issues.Indeed,we specifically

analyze CSR in the luxury context and empirically assess the con-

ditions under which CSR initiatives might improve consumers'

luxury brand perceptions. Second, we extend the literature on CSR

by showing that the type of CSR initiative may differentially affect

consumers’brand perceptions and purchasing intentions.Third,

our research is,to the best of our knowledge,the first to connect

different CSR dimensions with perceptions aboutluxury goods.

Specifically, we test whether external CSR initiatives are more likely

to gain higher consumer favor than internalinitiatives,or vice

versa.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section, we

describe the institutional setting and in section three we review the

main theoretical ideas, thereby providing the research hypotheses.

Section four describes the empirical design, while sections five, six

and seven contain the methodology and results of the three

empiricalstudies conducted.Finally,in section eight,we discuss

the theoretical and managerial implications of our work as well as

its limitations and directions for future studies.

2. Institutional background

While companies may be strongly committed to sustainable

development, the opportunity to develop and implement effective

CSR initiatives is often heavily affected by the specific “rules of the

game” (Thelen, 1999) at play in the different countries in which a

company operates (Halkos and Skouloudis, 2016). As stated by Xie

et al.(2017,p. 28),institutions refer to the “regulative,normative,

and cognitive structures that order and constrain human action,

providing stability to social behavior” (see also Xu and Yang, 2010).

More specifically, the institutional environment of a country refers

to the political and socio-economic environment, the bureaucracy,

the codified and non-codified norms of behavior,and the related

historical development ofa country's institutions (see Fifka and

Pobizhan,2014).Previous studies have shown that good institu-

tional environments strengthen the impact of CSR efforts on firms'

customer satisfaction (Xie et al.,2017).Interestingly,the institu-

tional environment of a country can be analyzed through the so-

called “national business systems approach” developed by

Whitley (1992) and used also to study national CSR characteristics

(e.g.,Habisch et al.,2011).As highlighted by Fifka and Pobizhan

(2014,p. 193),the nationalbusiness system of a country can be

mainly identified with “the politicalsystem,the culturalsystem,

the financial system,and the education and labor system.”

Consistent with this view of the institutional environment, past

research has demonstrated that the level of CSR penetration varies

across countries because of the discrepancies in the institutional

efficiency characterizing different countries (Marquis et al.,2007;

Welford, 2004). For instance, contexts characterized by the

Anglo-Saxon institutionalmodel seem to stimulate ethical and

social initiatives developed by companiesto a greater extent

compared to other contexts (Jackson and Apostolakou,2010).

Institutionalbarriers,however,may also depend on the specific

sector in which the company operates.According to Jackson and

Apostolakou (2010,p. 388),“sector-level institutions may be very

important in explaining the diffusion of ‘minimum standards’for

CSR,where firms respond to coercive and normative pressures of

sectoral-levelregulatory standardsor governance mechanisms

operating at the transnational scale”.

While the present research does not focus specifically on the

role of the institutional environments in driving companies'deci-

sion to engage in CSR initiatives, the framework we propose and the

results we show should be interpreted by taking into account the

differences among countries in terms of standards and legal sys-

tems at play. More specifically, when exploring the effectiveness of

CSR initiatives falling into the legal CSR dimension (Carroll, 1979,

1991),we acknowledge that the boundaries ofcompanies’legal

responsibility may be importantly shaped by the institutional

environment characterizing each country and often differentiating

that country from others.

3. Conceptual development

Past research in luxury has traditionally suggested that CSR is

not a prominent factor in luxury consumers' decision-making

(Davies et al., 2012; Griskevicius et al., 2010); one study even

found that CSR could undermine consumers' perceptions about the

quality of luxury goods (Achabou and Dekhili, 2013). Such findings

are grounded on the idea that luxury generally evokes hedonism,

excess, and ostentation (Cristini et al., 2017; De Barnier et al., 2012),

while CSR generally evokes sobriety, moderation and ethics

(Gladwin et al., 1995; Lochard and Murat,2011).Despite the prior

findings,however,there is burgeoning evidence that luxury and

CSR might be compatible after all (e.g., Janssen et al., 2014). Indeed,

a perceived fit between luxury and CSR may lead consumers to hold

positive attitudes towards luxury products when said products

elicit scarcity and ephemerality (Janssen et al.,2014).Consistent

with this, Kapferer (2010) argued that luxury and sustainable

development can converge when “both focus on rarity” (p.41).

Indeed, on the one hand, luxury is about high quality products that

are objectively rare because they employ rare materials and unique

craftsmanship skills. On the other hand, sustainable development is

about preserving natural resources by limiting the excessive use of

materials that can exceed the world's recycling capabilities

(Kapferer,2010).

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287278

In other words, luxury brands typically manufacture limited

quantities of products in order to be exclusive,and the quality of

those goods often means that they have a long lifecycle.Conse-

quently, luxury brands waste significantly fewer resources

compared to mass market brands; therefore,one could say that

luxury goods are inherently sustainable (Amatulliet al., 2017).

Following this logic, it could be argued that the luxury world has, in

many respects,the potentialto abide by the paradigm of cleaner

production,defined as “a systematically organized approach to

production activities,which has positive effects on the environ-

ment. These activities encompassresource use minimization,

improved eco-efficiency and source reduction, in order to improve

the environmental protection and to reduce risks to living organ-

isms” (Glavic and Lukman,2007,p. 1879).A recent work of De

Angelis et al. (2017) empirically supported the idea that luxury

brands can be both “gold and green” (p. 1516) in a study of

sustainability-driven luxury fashion product design, in which they

demonstrated thatconsumersmight sometime favorably view

luxury brands'new green products that are similar in design to

models produced by non-luxury companies specialized in green

production rather than similar in design to the luxury company's

previous non-green products.

Interestingly,while it is demonstrated that luxury companies

frequently engage in CSR activities that give a positive contribution

to the well-being of the environment and the society in which they

operate,how consumers react after knowing that a luxury brand

engages in CSR activities, and more specifically whether consumers

react differently to different types of CSR activities,is still unclear.

Importantly,by focusing on consumers'perceptions about com-

panies’CSR efforts,this research connects to studies thathave

demonstrated the positive effect of CSR on customer satisfaction in

non-luxury sectors (Louriero et al.,2012; Xie et al., 2017).

The starting point of our study of the role of CSR initiatives in

luxury is the well-established idea that CSR is a multidimensional

construct (D'Aprile and Mannarini, 2012; Pino et al., 2016). As very

recently noted by Arena et al. (2018), CSR is an “umbrella” concept

that includes a variety of practices aimed at fulfilling the expecta-

tion of different stakeholders.We use the multidimensional

approach of CSR proposed by Archie B. Carroll's (1979, 1991), which

is considered a seminalcontribution in the CSR domain,as our

reference theoreticalframework. According to Carroll, CSR en-

compasses four main dimensions e economic,legal,ethical,and

philanthropic e that correspond to four types of company re-

sponsibilities. Carroll portrayed such dimensions as a pyramid, with

the economic dimension,whereby companies should “make an

acceptable profit” (Carroll,1991,p. 141),at the bottom and the

philanthropic dimension,whereby companies should behave as

good corporate citizens,at the top. In the middle are the legal

dimension,whereby companies should abide by laws and regula-

tions, and the ethical dimension, whereby companies should avoid

morally unacceptable behaviors and respect human rights.

In this research, we categorize such four types of CSR initiatives

following the classification proposed by Pino et al.(2016) in their

study of consumers'attitudes toward genetically modified foods.

Those scholars advanced the idea that economic, legal, ethical and

philanthropic initiatives can be further grouped in two categories,

labelled internal and external CSR activities, based on their visibility

and noticeability for consumers.Specifically,according to the au-

thors, initiatives falling into the economic and ethical CSR di-

mensions (i.e.,reducing production costs and improving working

conditions) belong to the internal category because those initiatives

are, on the basis oftheir nature,less visible and less easy to be

noticed by consumers and public opinion than initiatives falling

into the legal and philanthropic CSR dimensions (i.e.,including

required information on product packaging and financially

supporting the construction ofa hospital in a needed territory),

which, consistently,belong to the externalcategory (Creyer and

Ross,1996; Singh et al.,2008).Of importance,while companies’

communication activities may certainly increase the visibility of

their internal CSR initiatives,those initiatives,compared to the

externalCSR ones,are inherently less visible for the reason that

consumers typically have harder time to detect if a company has

undertaken actions aimed improving internal efficiency or working

conditions versus actions aimed at abiding by legal product stan-

dards or donating resources for social causes.

We believe the visibility-based distinction of CSR initiatives into

internal versus external, introduced by Pino et al. (2016) in a study

of CSR perceptions in mass-market goods, is even more suitable to

the study of CSR in luxury because of the nature of luxury goods.

Indeed,many consumers buy luxury goods mainly to signal status

and prestige in social contexts (Han et al., 2010; Nelissen and

Meijers, 2011; Wang and Griskevicius, 2014; Wang and

Wallendorf,2006),if not to “impress others” e usually with re-

gard to their ability to pay particularly high prices for well-known

brands (Husic and Cicic,2009; Wiedmann et al.,2009).In other

words,luxury consumption is mainly related to consumers’expo-

sure to society (Kastanakis and Balabanis,2012).Interestingly,as

suggested by Steinhartet al. (2013), consumersmay respond

positively to environmental claims when those claims emphasize

status-related benefits for consumers.As a consequence,visibility

is not sufficient to define a brand as luxury one but it may be

essential to boost the prestige and the exclusivity of a luxury brand

(Fionda and Moore, 2009).

Building on this idea, we predict that luxury companies' external

CSR initiatives (i.e.,those related to the legaland philanthropic

dimensions) will be more effective than their internal CSR initia-

tives (i.e., those related to the economic and ethical dimensions) in

boosting consumers' WTB luxury products. Such a prediction rests

on the argument that the higher public visibility of externalCSR

initiatives (Creyer and Ross,1996; Singh et al.,2008) will seem

more consistent with luxury products' status-signaling orientation.

In other words, because luxury consumption implies a desire to

communicate something to others,consumers will be particularly

attracted by brand elements thatare especially noticeable and

recognizable in the marketat large. In essence,we argue that,

because external CSR aligns with the status-signaling positioning

(Du et al., 2007) of the luxury brand, these initiatives (i.e., those in

the legal and philanthropic domains)will be likely to increase

consumers'perceptions of the brand's luxuriousness and, by

extension, their WTB. To clarify, we are not predicting that visibility

always and necessarily increases perceived luxuriousness,as we

acknowledge that there are many cases where this does not

happen; rather, we predict that, compared to internal CSR activities,

externalCSR activities willbe more likely to increase perceived

luxuriousness. Formally:

H1. Compared to internal CSR initiatives,external CSR initiatives

undertaken by a brand are more likely to increase consumers'

perceptionsof that brand's luxuriousness,leading to a higher

consumer willingness to buy products from that brand.

While it is true that luxury goods typically serve a status-

signaling function,it is also true that consumers'dispositions and

inner motivations toward luxury purchasing can vary.Indeed,the

literature suggests that people's motives for luxury consumption

can be externalor internal (Eastman and Eastman,2015).Some

customers may buy luxury goods mainly to demonstrate their

status and prestige,which qualifies as an externalized approach.

Other customers purchase luxury products to satisfy their personal

taste and style, which qualifies as an internalized approach

(Amatulli et al.,2015; Han et al.,2010).

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287 279

quantities of products in order to be exclusive,and the quality of

those goods often means that they have a long lifecycle.Conse-

quently, luxury brands waste significantly fewer resources

compared to mass market brands; therefore,one could say that

luxury goods are inherently sustainable (Amatulliet al., 2017).

Following this logic, it could be argued that the luxury world has, in

many respects,the potentialto abide by the paradigm of cleaner

production,defined as “a systematically organized approach to

production activities,which has positive effects on the environ-

ment. These activities encompassresource use minimization,

improved eco-efficiency and source reduction, in order to improve

the environmental protection and to reduce risks to living organ-

isms” (Glavic and Lukman,2007,p. 1879).A recent work of De

Angelis et al. (2017) empirically supported the idea that luxury

brands can be both “gold and green” (p. 1516) in a study of

sustainability-driven luxury fashion product design, in which they

demonstrated thatconsumersmight sometime favorably view

luxury brands'new green products that are similar in design to

models produced by non-luxury companies specialized in green

production rather than similar in design to the luxury company's

previous non-green products.

Interestingly,while it is demonstrated that luxury companies

frequently engage in CSR activities that give a positive contribution

to the well-being of the environment and the society in which they

operate,how consumers react after knowing that a luxury brand

engages in CSR activities, and more specifically whether consumers

react differently to different types of CSR activities,is still unclear.

Importantly,by focusing on consumers'perceptions about com-

panies’CSR efforts,this research connects to studies thathave

demonstrated the positive effect of CSR on customer satisfaction in

non-luxury sectors (Louriero et al.,2012; Xie et al., 2017).

The starting point of our study of the role of CSR initiatives in

luxury is the well-established idea that CSR is a multidimensional

construct (D'Aprile and Mannarini, 2012; Pino et al., 2016). As very

recently noted by Arena et al. (2018), CSR is an “umbrella” concept

that includes a variety of practices aimed at fulfilling the expecta-

tion of different stakeholders.We use the multidimensional

approach of CSR proposed by Archie B. Carroll's (1979, 1991), which

is considered a seminalcontribution in the CSR domain,as our

reference theoreticalframework. According to Carroll, CSR en-

compasses four main dimensions e economic,legal,ethical,and

philanthropic e that correspond to four types of company re-

sponsibilities. Carroll portrayed such dimensions as a pyramid, with

the economic dimension,whereby companies should “make an

acceptable profit” (Carroll,1991,p. 141),at the bottom and the

philanthropic dimension,whereby companies should behave as

good corporate citizens,at the top. In the middle are the legal

dimension,whereby companies should abide by laws and regula-

tions, and the ethical dimension, whereby companies should avoid

morally unacceptable behaviors and respect human rights.

In this research, we categorize such four types of CSR initiatives

following the classification proposed by Pino et al.(2016) in their

study of consumers'attitudes toward genetically modified foods.

Those scholars advanced the idea that economic, legal, ethical and

philanthropic initiatives can be further grouped in two categories,

labelled internal and external CSR activities, based on their visibility

and noticeability for consumers.Specifically,according to the au-

thors, initiatives falling into the economic and ethical CSR di-

mensions (i.e.,reducing production costs and improving working

conditions) belong to the internal category because those initiatives

are, on the basis oftheir nature,less visible and less easy to be

noticed by consumers and public opinion than initiatives falling

into the legal and philanthropic CSR dimensions (i.e.,including

required information on product packaging and financially

supporting the construction ofa hospital in a needed territory),

which, consistently,belong to the externalcategory (Creyer and

Ross,1996; Singh et al.,2008).Of importance,while companies’

communication activities may certainly increase the visibility of

their internal CSR initiatives,those initiatives,compared to the

externalCSR ones,are inherently less visible for the reason that

consumers typically have harder time to detect if a company has

undertaken actions aimed improving internal efficiency or working

conditions versus actions aimed at abiding by legal product stan-

dards or donating resources for social causes.

We believe the visibility-based distinction of CSR initiatives into

internal versus external, introduced by Pino et al. (2016) in a study

of CSR perceptions in mass-market goods, is even more suitable to

the study of CSR in luxury because of the nature of luxury goods.

Indeed,many consumers buy luxury goods mainly to signal status

and prestige in social contexts (Han et al., 2010; Nelissen and

Meijers, 2011; Wang and Griskevicius, 2014; Wang and

Wallendorf,2006),if not to “impress others” e usually with re-

gard to their ability to pay particularly high prices for well-known

brands (Husic and Cicic,2009; Wiedmann et al.,2009).In other

words,luxury consumption is mainly related to consumers’expo-

sure to society (Kastanakis and Balabanis,2012).Interestingly,as

suggested by Steinhartet al. (2013), consumersmay respond

positively to environmental claims when those claims emphasize

status-related benefits for consumers.As a consequence,visibility

is not sufficient to define a brand as luxury one but it may be

essential to boost the prestige and the exclusivity of a luxury brand

(Fionda and Moore, 2009).

Building on this idea, we predict that luxury companies' external

CSR initiatives (i.e.,those related to the legaland philanthropic

dimensions) will be more effective than their internal CSR initia-

tives (i.e., those related to the economic and ethical dimensions) in

boosting consumers' WTB luxury products. Such a prediction rests

on the argument that the higher public visibility of externalCSR

initiatives (Creyer and Ross,1996; Singh et al.,2008) will seem

more consistent with luxury products' status-signaling orientation.

In other words, because luxury consumption implies a desire to

communicate something to others,consumers will be particularly

attracted by brand elements thatare especially noticeable and

recognizable in the marketat large. In essence,we argue that,

because external CSR aligns with the status-signaling positioning

(Du et al., 2007) of the luxury brand, these initiatives (i.e., those in

the legal and philanthropic domains)will be likely to increase

consumers'perceptions of the brand's luxuriousness and, by

extension, their WTB. To clarify, we are not predicting that visibility

always and necessarily increases perceived luxuriousness,as we

acknowledge that there are many cases where this does not

happen; rather, we predict that, compared to internal CSR activities,

externalCSR activities willbe more likely to increase perceived

luxuriousness. Formally:

H1. Compared to internal CSR initiatives,external CSR initiatives

undertaken by a brand are more likely to increase consumers'

perceptionsof that brand's luxuriousness,leading to a higher

consumer willingness to buy products from that brand.

While it is true that luxury goods typically serve a status-

signaling function,it is also true that consumers'dispositions and

inner motivations toward luxury purchasing can vary.Indeed,the

literature suggests that people's motives for luxury consumption

can be externalor internal (Eastman and Eastman,2015).Some

customers may buy luxury goods mainly to demonstrate their

status and prestige,which qualifies as an externalized approach.

Other customers purchase luxury products to satisfy their personal

taste and style, which qualifies as an internalized approach

(Amatulli et al.,2015; Han et al.,2010).

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287 279

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

As emphasized by Eastman and Eastman (2015),externally-

motivated luxury consumption may lead to more public con-

sumption of status products and more conspicuous-style con-

sumption. In other words, consumers who mainly have an

externalized luxury approach place greaterimportance on the

“visibility” of luxury goods than those who mainly have an inter-

nalized luxury approach (Nueno and Quelch, 1998).This visibility

can be captured by the idea of conspicuous consumption (e.g.,

Jaikumar and Sarin,2015; Wang and Griskevicius,2014),which

refers to the tendency to buy symbolic and visible products with

the aim of communicating a distinctive self-image to others

(Chaudhuri et al.,2011; Fuchs et al.,2013).

Based on this reasoning,we expect that the effectiveness of

external versus internal CSR initiatives in driving consumers’ WTB

luxury products will depend on the perceived personalbenefits

that the consumer derives from those initiatives (Bhattacharya

et al.,2009).More specifically,we predict that actions related to

externalCSR dimensions,such as those in the legaland philan-

thropic domains (Eastman et al., 1999),will be more appealing to

such customers who adoptan externalized approach to luxury

consumption (Chaudhuri et al., 2011). In contrast, consumers with a

more internalized approach to luxury will value those dimensions

to a lesser degree.

Moreover, while status and conspicuous consumption have

conceptual overlap and could be perceived as identical (e.g.,

Bernhaim,1994; Marcoux et al.,1997),we also acknowledge the

argument that they are not exactly the same,and, consequently,

should be measured in differentways (O'Cass and Frost,2002;

O'Cass and McEwen,2004). Indeed,O'Cass and McEwen (2004)

demonstrated that status and conspicuous consumption are

distinct constructs that reflect a different set of consumer behaviors

and consumption motives: Status consumption can be defined as

“the behavioural tendency to value status and acquire and consume

products that provide status to the individual”,while conspicuous

consumption as “the tendency for individuals to enhance their

image,through overt consumption of possessions,which commu-

nicates status to others” (O'Cass and McEwen, 2004, p. 34). In other

words, the driving difference between the two is that status con-

sumption is affected by consumers'self-monitoring (whereby

consumers aim to enhance their overall image in social contexts),

whereas conspicuous consumption is affected by interpersonal

influences (whereby consumers aim to gain approvalfrom their

reference group by overtly displaying visible products) (O'Cass and

Frost, 2002). Indeed, according to O'Cass and McEwen (2004),

“status consumption is more a matter of consumers' desires to gain

prestige from the acquisition of status-laden products and brands;

however, conspicuous consumption focuses on the visual display or

overt usage of products in the presence of others” (p.27).

Based on the above, we predict that the positive effect of

communicating luxury brands' legal and philanthropic (vs. economic

and ethical) CSR initiatives on consumers' WTB said brands’ products

will be magnified for consumers with a high tendency toward status

consumption and conspicuous consumption. Formally:

H2. The effect of external CSR initiatives on consumers'willing-

ness to buy luxury goods over internal CSR initiatives will be

magnified for consumers with a higher rather than a lower status

consumption orientation.

H3. The effect of external CSR initiatives on consumers'willing-

ness to buy luxury goods over internal CSR initiatives will be

magnified for consumers with a higher rather than a lower con-

spicuous consumption orientation.

It is important to note that hypothesizing that the general effect

in H1 being moderated by consumer-related factors (as per H2 and

H3) is in line with recent work in luxury and sustainability.De

Angelis et al. (2017),for example,have shown that such a con-

sumers'characteristics as their prior knowledge about a luxury

brand moderates the effectof introducing a new green luxury

product that resembles a non-luxury,green company's previous

model versus one that resembles a luxury company's previous

model on luxury brand evaluation. In particular, their results show

that consumers with higher luxury brand knowledge,and thus

those who are more concerned about the luxury brand's status-

signaling function,are more likely than those with a lower luxury

brand knowledge to prefer a new green luxury productthat is

similar in design to a luxury brand's previous models rather than

similar in design to a model produced by a non-luxury brand

specialized in green product.

In the following, we describe three experiments designed to

empirically test our hypotheses.Taken together,they provide evi-

dence for our theoretical approach.We begin with a study on the

effect of externalCSR on WTB, as well as the mediating role of

brand luxuriousness.

4. Overview of studies

Study 1 was an in-lab experiment conducted to test H1; Study 2

was a field experiment designed to test H2 (status consumption);

and Study 3 was an online experiment designed to test H3. Across

all the studies,we assessed our focal constructs using appropriate

measures by following a question order that reflected the hy-

pothesized causal chain. In Study 1,for instance, we measured the

perceived luxuriousness related to the brand, which played the role

of mediator,before the dependent variable. In Studies 2 and 3,we

respectively measured the participants'status consumption and

conspicuous consumption,which played the role ofmoderators,

before the independent variable.We considered that a different

question order would have been potentially distorting,given the

nature of the dependent variable we employed across the three

studies,that is the WTB.Indeed,given that both our moderators

and dependent variable were related to luxury consumption,we

wanted to reduce the risk of having participants’ answers about the

former being influenced by those about the latter.Moreover,we

adopted the same measurement for the dependent variable in all

studies in order to confer robustness to the results.

5. Study 1: the mediating role of consumers’luxury brand

perception

Study 1 sought to test H1 by exploring the mediational role of

consumers' perceptions about a brand's luxuriousness on the effect

of external versus internal CSR initiatives on consumers'WTB.

More specifically,we expected external CSR initiatives (i.e.,in the

legal and philanthropic dimensions) to enhance perceived brand

luxuriousness more than internalCSR initiatives (i.e.,in the eco-

nomic and ethical dimensions),thereby increasing consumers'

WTB products for that brand.In short,this study investigated the

effect of CSR initiatives on consumers'behaviouralintentions,as

well as the mechanism driving such an effect.

5.1.Design and procedure

One hundred and nineteen participants (70 females,49 males;

M Age ¼ 32.95,SDAge ¼ 10.65),who encompassed both workers and

university students living in a large European city,were randomly

assigned to a two-cell (CSR dimensions:external vs. internal)

between-subjects experiment.Participants completed their ques-

tionnaire in a laboratory setting. No monetary incentives were used

for motivating respondents to participate to the experiment.The

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287280

motivated luxury consumption may lead to more public con-

sumption of status products and more conspicuous-style con-

sumption. In other words, consumers who mainly have an

externalized luxury approach place greaterimportance on the

“visibility” of luxury goods than those who mainly have an inter-

nalized luxury approach (Nueno and Quelch, 1998).This visibility

can be captured by the idea of conspicuous consumption (e.g.,

Jaikumar and Sarin,2015; Wang and Griskevicius,2014),which

refers to the tendency to buy symbolic and visible products with

the aim of communicating a distinctive self-image to others

(Chaudhuri et al.,2011; Fuchs et al.,2013).

Based on this reasoning,we expect that the effectiveness of

external versus internal CSR initiatives in driving consumers’ WTB

luxury products will depend on the perceived personalbenefits

that the consumer derives from those initiatives (Bhattacharya

et al.,2009).More specifically,we predict that actions related to

externalCSR dimensions,such as those in the legaland philan-

thropic domains (Eastman et al., 1999),will be more appealing to

such customers who adoptan externalized approach to luxury

consumption (Chaudhuri et al., 2011). In contrast, consumers with a

more internalized approach to luxury will value those dimensions

to a lesser degree.

Moreover, while status and conspicuous consumption have

conceptual overlap and could be perceived as identical (e.g.,

Bernhaim,1994; Marcoux et al.,1997),we also acknowledge the

argument that they are not exactly the same,and, consequently,

should be measured in differentways (O'Cass and Frost,2002;

O'Cass and McEwen,2004). Indeed,O'Cass and McEwen (2004)

demonstrated that status and conspicuous consumption are

distinct constructs that reflect a different set of consumer behaviors

and consumption motives: Status consumption can be defined as

“the behavioural tendency to value status and acquire and consume

products that provide status to the individual”,while conspicuous

consumption as “the tendency for individuals to enhance their

image,through overt consumption of possessions,which commu-

nicates status to others” (O'Cass and McEwen, 2004, p. 34). In other

words, the driving difference between the two is that status con-

sumption is affected by consumers'self-monitoring (whereby

consumers aim to enhance their overall image in social contexts),

whereas conspicuous consumption is affected by interpersonal

influences (whereby consumers aim to gain approvalfrom their

reference group by overtly displaying visible products) (O'Cass and

Frost, 2002). Indeed, according to O'Cass and McEwen (2004),

“status consumption is more a matter of consumers' desires to gain

prestige from the acquisition of status-laden products and brands;

however, conspicuous consumption focuses on the visual display or

overt usage of products in the presence of others” (p.27).

Based on the above, we predict that the positive effect of

communicating luxury brands' legal and philanthropic (vs. economic

and ethical) CSR initiatives on consumers' WTB said brands’ products

will be magnified for consumers with a high tendency toward status

consumption and conspicuous consumption. Formally:

H2. The effect of external CSR initiatives on consumers'willing-

ness to buy luxury goods over internal CSR initiatives will be

magnified for consumers with a higher rather than a lower status

consumption orientation.

H3. The effect of external CSR initiatives on consumers'willing-

ness to buy luxury goods over internal CSR initiatives will be

magnified for consumers with a higher rather than a lower con-

spicuous consumption orientation.

It is important to note that hypothesizing that the general effect

in H1 being moderated by consumer-related factors (as per H2 and

H3) is in line with recent work in luxury and sustainability.De

Angelis et al. (2017),for example,have shown that such a con-

sumers'characteristics as their prior knowledge about a luxury

brand moderates the effectof introducing a new green luxury

product that resembles a non-luxury,green company's previous

model versus one that resembles a luxury company's previous

model on luxury brand evaluation. In particular, their results show

that consumers with higher luxury brand knowledge,and thus

those who are more concerned about the luxury brand's status-

signaling function,are more likely than those with a lower luxury

brand knowledge to prefer a new green luxury productthat is

similar in design to a luxury brand's previous models rather than

similar in design to a model produced by a non-luxury brand

specialized in green product.

In the following, we describe three experiments designed to

empirically test our hypotheses.Taken together,they provide evi-

dence for our theoretical approach.We begin with a study on the

effect of externalCSR on WTB, as well as the mediating role of

brand luxuriousness.

4. Overview of studies

Study 1 was an in-lab experiment conducted to test H1; Study 2

was a field experiment designed to test H2 (status consumption);

and Study 3 was an online experiment designed to test H3. Across

all the studies,we assessed our focal constructs using appropriate

measures by following a question order that reflected the hy-

pothesized causal chain. In Study 1,for instance, we measured the

perceived luxuriousness related to the brand, which played the role

of mediator,before the dependent variable. In Studies 2 and 3,we

respectively measured the participants'status consumption and

conspicuous consumption,which played the role ofmoderators,

before the independent variable.We considered that a different

question order would have been potentially distorting,given the

nature of the dependent variable we employed across the three

studies,that is the WTB.Indeed,given that both our moderators

and dependent variable were related to luxury consumption,we

wanted to reduce the risk of having participants’ answers about the

former being influenced by those about the latter.Moreover,we

adopted the same measurement for the dependent variable in all

studies in order to confer robustness to the results.

5. Study 1: the mediating role of consumers’luxury brand

perception

Study 1 sought to test H1 by exploring the mediational role of

consumers' perceptions about a brand's luxuriousness on the effect

of external versus internal CSR initiatives on consumers'WTB.

More specifically,we expected external CSR initiatives (i.e.,in the

legal and philanthropic dimensions) to enhance perceived brand

luxuriousness more than internalCSR initiatives (i.e.,in the eco-

nomic and ethical dimensions),thereby increasing consumers'

WTB products for that brand.In short,this study investigated the

effect of CSR initiatives on consumers'behaviouralintentions,as

well as the mechanism driving such an effect.

5.1.Design and procedure

One hundred and nineteen participants (70 females,49 males;

M Age ¼ 32.95,SDAge ¼ 10.65),who encompassed both workers and

university students living in a large European city,were randomly

assigned to a two-cell (CSR dimensions:external vs. internal)

between-subjects experiment.Participants completed their ques-

tionnaire in a laboratory setting. No monetary incentives were used

for motivating respondents to participate to the experiment.The

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287280

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

questionnaire was delivered through the Qualtrics platform so that

we could easily randomize the experimentalconditions.Partici-

pants were first told they were participating in a survey about their

perceptions of certain brands and were then asked to complete the

questionnaire via a tablet.They first read a scenario regarding a

fictitious company called Shine (please see the Appendix).This

company was described as producing leather goods and under-

taking two kinds of CSR initiatives: either economic and ethical (in

the internal CSR condition) or legal and philanthropic initiatives (in

the external CSR condition). More specifically, the economic

initiative consisted of the company buying a software tool to

optimize its production process,thereby reducing its production

costs and improving profits; the ethical initiative involved the

company offering health care and insurance benefits for its work-

force; the legal initiative entailed the company becoming

compliant with raw material processing regulations and adding its

certification to all its products; finally,the philanthropic initiative

involved the company donating a significant amount of money to

build a new pediatric hospital.

We pretested the effectiveness of the CSR dimensional manip-

ulation with a sample of121 respondents recruited via Amazon

Mechanical Turk. Such participants were asked to what extent they

perceived the described initiatives as visible and observable from

outside the company (e.g., by people not working for the company,

such as consumers)on a seven-point scale (1 ¼ notvisible and

observable at all, 7 ¼ extremely visible and observable). The results

revealed that,as expected,respondents in the externalCSR con-

dition perceived the brand's initiatives as more visible and

observable than those in the internal CSR condition (M exter-

nal ¼ 5.02,SD ¼ 1.21 vs.M internal¼ 4.00,SD ¼ 1.56;t(119) ¼ 2.67,

p ¼ .01).

Immediately following the manipulation, participants were

asked to rate how they perceived the brand using the 20-item

(seven-point bipolar) Brand Luxury Index (BLI) scale (see

Vigneron and Johnson,2004).The BLI scale captures the extent to

which consumers perceive a brand as “prestigious,”“elitist,”

“exclusive,” and so on.Finally, we measured respondents’WTB

using the three-item scale from Dodds et al. (1991; “I would buy a

product from this brand,” “I could consider buying a product from

this brand,” and “The likelihood I buy a product from this brand is

high”),which respondents answered on seven-point Likert scales

(1 ¼ strongly disagree, 7 ¼ strongly agree).

5.2. Results and discussion

We combined the scores from the 20 items comprising the BLI

scale (a ¼ 0.90)and three items assessingparticipants’ WTB

(a ¼ 0.88) to obtain measures of the mediator and the dependent

variable,respectively.We employed Model 4 of the PROCESS SPSS

Macro (Hayes, 2013) to test the mediation model. BLI served as the

mediator of the relationship between the CSR dimensions and

WTB.

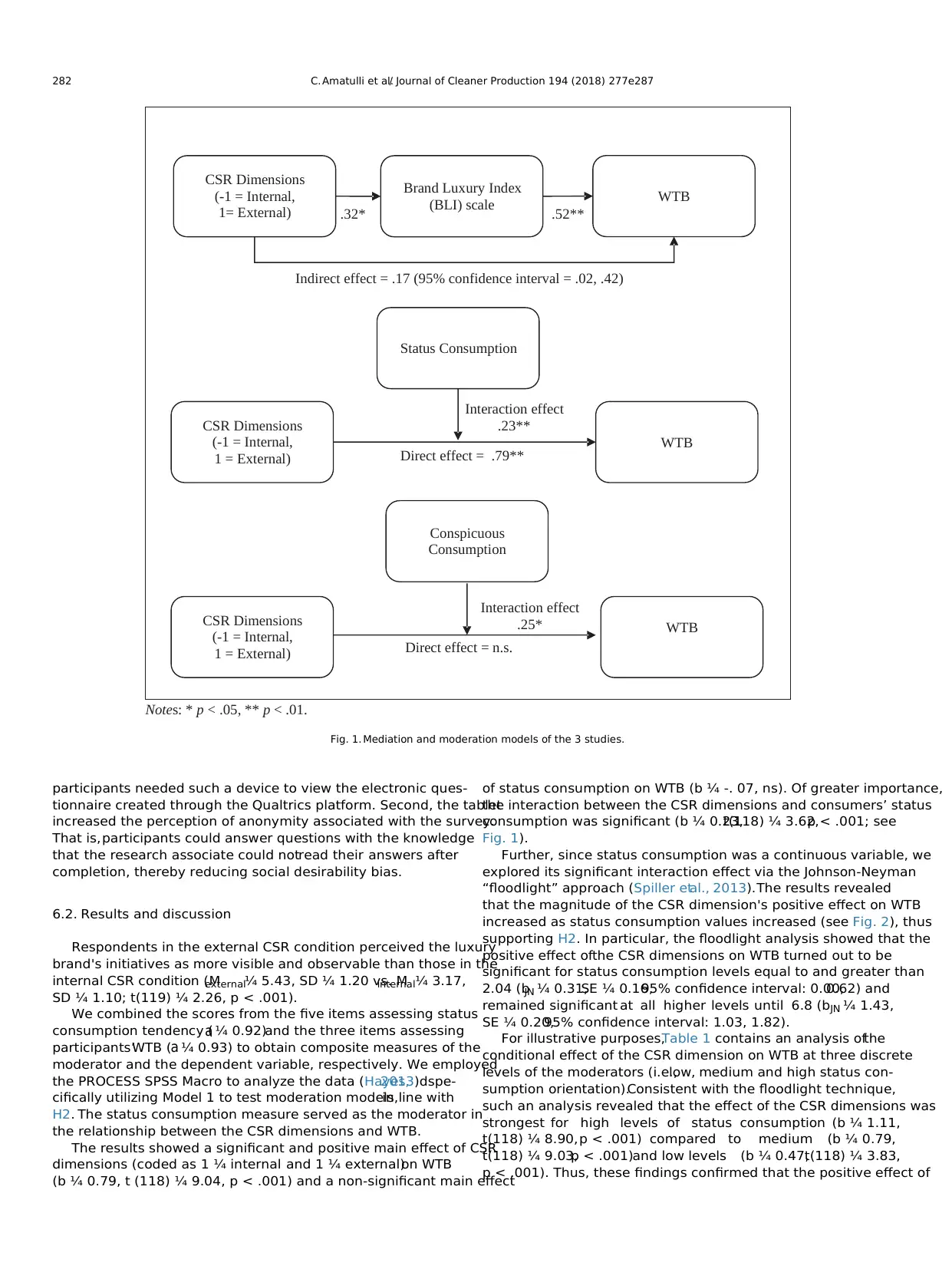

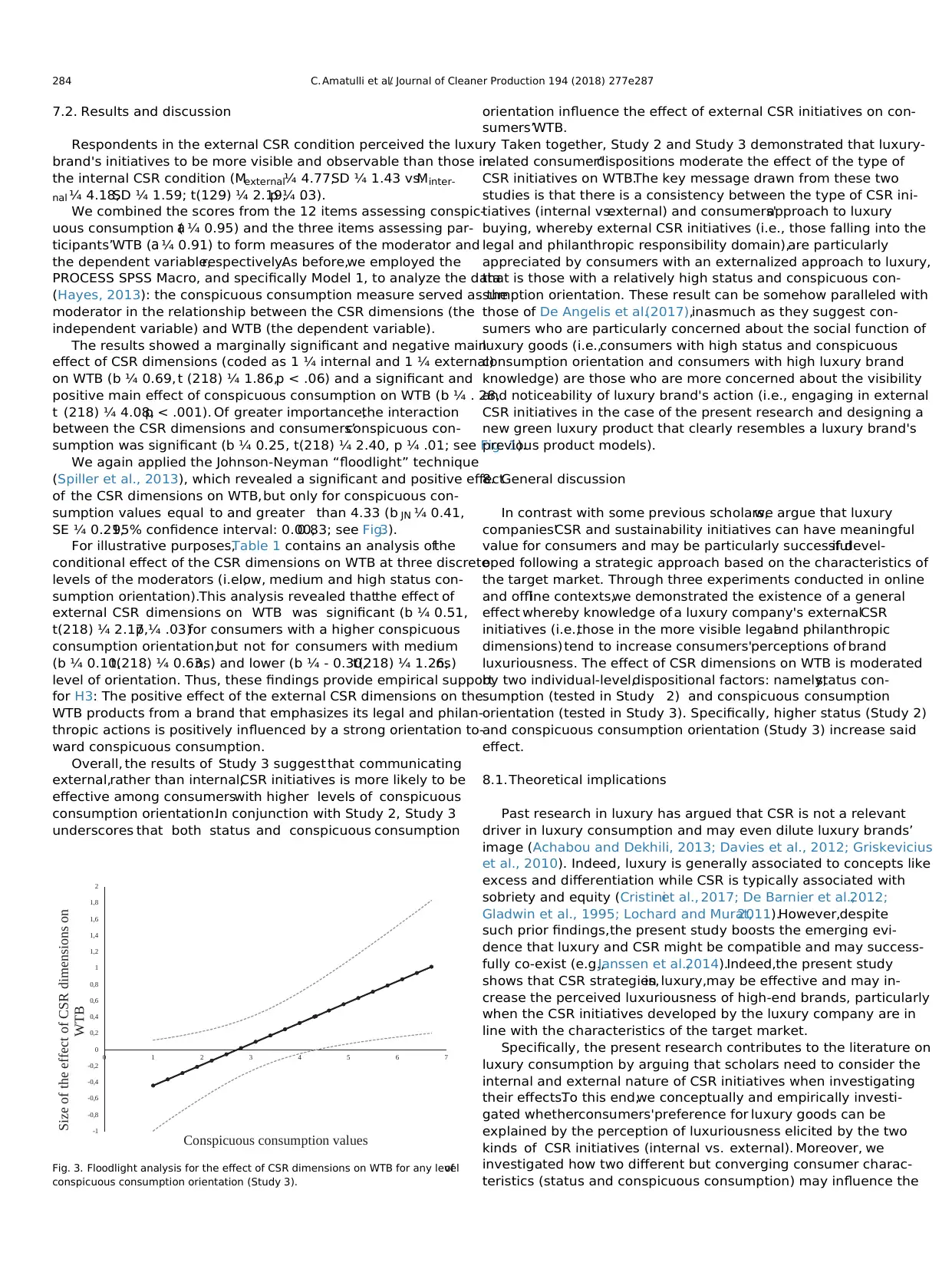

The results showed a significantand positive effect(b ¼ .32,

t(116) ¼ 2.15,p ¼ .03) of the CSR dimensions (coded

as 1 ¼ internal and 1 ¼ external) on the BLI,which suggests that

reading about legal and philanthropic initiatives increased

perceived brand luxuriousness more than reading about economic

and ethical initiatives. Moreover,BLI had a positive and significant

effect on WTB (b ¼ 0.52,t(116) ¼ 3.87,p < .001).Importantly,the

results revealed a non-significant (b ¼ - 0.07, ns) direct effect of CSR

dimensions on the WTB,but a significant and positive indirect ef-

fect of CSR dimensions on the WTB via the BLI (b ¼ 0.17,95% con-

fidence interval: 0.02, 0.42; see Fig. 1 and Table 1 for a summary of

results). Thus, the results indicate an indirect-only effect of the CSR

dimensions on consumers’ WTB via brand luxuriousness (see Zhao

et al., 2010). In full support of H1, these findings confirmed that the

BLI mediated the effect of externalCSR dimensions on the WTB

products from the brand that emphasizes its legaland philan-

thropic actions.

Overall,Study 1 suggests that consumers have a higher WTB a

product from a brand engaging in initiatives belonging to the

external(rather than internal) CSR dimensions because knowing

about the former boosts that brand's perceived luxuriousness. This

finding is consistent with our proposition that CSR initiatives in

luxury may be differentially effective in influencing consumers'

purchasing attitudes depending on whether such initiatives are

internal versus external in nature. In particular, the finding in Study

1 is in line with our conceptualization that more visible initiatives

trigger consumer favor because they have a better fitwith the

typical social orientation characterizing luxury purchases.More-

over,the findings of Study 1 are in line with those shown in Pino

et al.’s (2016) work in a different,non-luxury context,as these

authors found that consumers' perceptions about genetically

modified foods producers'legal and philanthropic responsibilities

favorably affect consumers'attitudes and intention to buy geneti-

cally modified food.

6. Study 2: the moderating role of status consumption

Study 2 aimed to test H2 by exploring whether the effect of CSR

dimensions on consumers'WTB is moderated by a consumer's

status consumption orientation.We expected thatthe effect of

external(compared to internal)CSR initiatives on WTB will be

magnified for a consumer who has a high (rather than low) ten-

dency toward status consumption. In other words,this study tests

the notion that luxury brands' external (vs. internal) CSR initiatives

might be particularly appreciated by luxury consumers who

possess a relatively high desire to elevate their social position.

6.1.Design and procedure

One hundred and twenty-one participants (58 females, 63

males; MAge ¼ 36.99, SDAge ¼ 10.52) were randomly intercepted in a

luxury mall and assigned to one of two conditions (CSR di-

mensions: externalvs. internal) within a two-cell,between-sub-

jects experiment, similar to Study 1's design. No monetary

incentives were used for motivating participants to participate to

the experiment.Also in this case the questionnaire was created

through the Qualtrics platform in order to randomize the experi-

mental conditions; participants completed it using a tablet. In order

to pursue both control and realism (Levitt and List,2009),partici-

pants were asked to complete the questionnaire while seated in a

dedicated corner of a specific luxury store. In this way, participants

were in a quiet environment but stillwithin a realistic shopping

context. Participantswere first asked to complete a five-item

measure of status consumption (Eastman etal., 1999; e.g., “I

would buy a product only because it is a status symbol,” “Iam

interested in buying new status-symbolproducts”) using seven-

point Likert scales (1 ¼ strongly disagree,7 ¼ strongly agree).

Next, participantsread scenarios describing a luxury company

(Shine,i.e., the same as in Study 1) undertaking either external

(economic and ethical) or internal(legal and philanthropic) CSR

initiatives,depending on the condition participants were assigned

to (please see the Appendix). Subsequently,we checked our

manipulation using the same measure used in Study 1's pretest.

Finally,participants were asked to complete the same three-item

measure employed in Study 1 that assessed their WTB products

from Shine.

It is worth noting that in both Study 1 and Study 2,the ques-

tionnaire was administered via a tablet for two reasons. First,

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287 281

we could easily randomize the experimentalconditions.Partici-

pants were first told they were participating in a survey about their

perceptions of certain brands and were then asked to complete the

questionnaire via a tablet.They first read a scenario regarding a

fictitious company called Shine (please see the Appendix).This

company was described as producing leather goods and under-

taking two kinds of CSR initiatives: either economic and ethical (in

the internal CSR condition) or legal and philanthropic initiatives (in

the external CSR condition). More specifically, the economic

initiative consisted of the company buying a software tool to

optimize its production process,thereby reducing its production

costs and improving profits; the ethical initiative involved the

company offering health care and insurance benefits for its work-

force; the legal initiative entailed the company becoming

compliant with raw material processing regulations and adding its

certification to all its products; finally,the philanthropic initiative

involved the company donating a significant amount of money to

build a new pediatric hospital.

We pretested the effectiveness of the CSR dimensional manip-

ulation with a sample of121 respondents recruited via Amazon

Mechanical Turk. Such participants were asked to what extent they

perceived the described initiatives as visible and observable from

outside the company (e.g., by people not working for the company,

such as consumers)on a seven-point scale (1 ¼ notvisible and

observable at all, 7 ¼ extremely visible and observable). The results

revealed that,as expected,respondents in the externalCSR con-

dition perceived the brand's initiatives as more visible and

observable than those in the internal CSR condition (M exter-

nal ¼ 5.02,SD ¼ 1.21 vs.M internal¼ 4.00,SD ¼ 1.56;t(119) ¼ 2.67,

p ¼ .01).

Immediately following the manipulation, participants were

asked to rate how they perceived the brand using the 20-item

(seven-point bipolar) Brand Luxury Index (BLI) scale (see

Vigneron and Johnson,2004).The BLI scale captures the extent to

which consumers perceive a brand as “prestigious,”“elitist,”

“exclusive,” and so on.Finally, we measured respondents’WTB

using the three-item scale from Dodds et al. (1991; “I would buy a

product from this brand,” “I could consider buying a product from

this brand,” and “The likelihood I buy a product from this brand is

high”),which respondents answered on seven-point Likert scales

(1 ¼ strongly disagree, 7 ¼ strongly agree).

5.2. Results and discussion

We combined the scores from the 20 items comprising the BLI

scale (a ¼ 0.90)and three items assessingparticipants’ WTB

(a ¼ 0.88) to obtain measures of the mediator and the dependent

variable,respectively.We employed Model 4 of the PROCESS SPSS

Macro (Hayes, 2013) to test the mediation model. BLI served as the

mediator of the relationship between the CSR dimensions and

WTB.

The results showed a significantand positive effect(b ¼ .32,

t(116) ¼ 2.15,p ¼ .03) of the CSR dimensions (coded

as 1 ¼ internal and 1 ¼ external) on the BLI,which suggests that

reading about legal and philanthropic initiatives increased

perceived brand luxuriousness more than reading about economic

and ethical initiatives. Moreover,BLI had a positive and significant

effect on WTB (b ¼ 0.52,t(116) ¼ 3.87,p < .001).Importantly,the

results revealed a non-significant (b ¼ - 0.07, ns) direct effect of CSR

dimensions on the WTB,but a significant and positive indirect ef-

fect of CSR dimensions on the WTB via the BLI (b ¼ 0.17,95% con-

fidence interval: 0.02, 0.42; see Fig. 1 and Table 1 for a summary of

results). Thus, the results indicate an indirect-only effect of the CSR

dimensions on consumers’ WTB via brand luxuriousness (see Zhao

et al., 2010). In full support of H1, these findings confirmed that the

BLI mediated the effect of externalCSR dimensions on the WTB

products from the brand that emphasizes its legaland philan-

thropic actions.

Overall,Study 1 suggests that consumers have a higher WTB a

product from a brand engaging in initiatives belonging to the

external(rather than internal) CSR dimensions because knowing

about the former boosts that brand's perceived luxuriousness. This

finding is consistent with our proposition that CSR initiatives in

luxury may be differentially effective in influencing consumers'

purchasing attitudes depending on whether such initiatives are

internal versus external in nature. In particular, the finding in Study

1 is in line with our conceptualization that more visible initiatives

trigger consumer favor because they have a better fitwith the

typical social orientation characterizing luxury purchases.More-

over,the findings of Study 1 are in line with those shown in Pino

et al.’s (2016) work in a different,non-luxury context,as these

authors found that consumers' perceptions about genetically

modified foods producers'legal and philanthropic responsibilities

favorably affect consumers'attitudes and intention to buy geneti-

cally modified food.

6. Study 2: the moderating role of status consumption

Study 2 aimed to test H2 by exploring whether the effect of CSR

dimensions on consumers'WTB is moderated by a consumer's

status consumption orientation.We expected thatthe effect of

external(compared to internal)CSR initiatives on WTB will be

magnified for a consumer who has a high (rather than low) ten-

dency toward status consumption. In other words,this study tests

the notion that luxury brands' external (vs. internal) CSR initiatives

might be particularly appreciated by luxury consumers who

possess a relatively high desire to elevate their social position.

6.1.Design and procedure

One hundred and twenty-one participants (58 females, 63

males; MAge ¼ 36.99, SDAge ¼ 10.52) were randomly intercepted in a

luxury mall and assigned to one of two conditions (CSR di-

mensions: externalvs. internal) within a two-cell,between-sub-

jects experiment, similar to Study 1's design. No monetary

incentives were used for motivating participants to participate to

the experiment.Also in this case the questionnaire was created

through the Qualtrics platform in order to randomize the experi-

mental conditions; participants completed it using a tablet. In order

to pursue both control and realism (Levitt and List,2009),partici-

pants were asked to complete the questionnaire while seated in a

dedicated corner of a specific luxury store. In this way, participants

were in a quiet environment but stillwithin a realistic shopping

context. Participantswere first asked to complete a five-item

measure of status consumption (Eastman etal., 1999; e.g., “I

would buy a product only because it is a status symbol,” “Iam

interested in buying new status-symbolproducts”) using seven-

point Likert scales (1 ¼ strongly disagree,7 ¼ strongly agree).

Next, participantsread scenarios describing a luxury company

(Shine,i.e., the same as in Study 1) undertaking either external

(economic and ethical) or internal(legal and philanthropic) CSR

initiatives,depending on the condition participants were assigned

to (please see the Appendix). Subsequently,we checked our

manipulation using the same measure used in Study 1's pretest.

Finally,participants were asked to complete the same three-item

measure employed in Study 1 that assessed their WTB products

from Shine.

It is worth noting that in both Study 1 and Study 2,the ques-

tionnaire was administered via a tablet for two reasons. First,

C. Amatulli et al./ Journal of Cleaner Production 194 (2018) 277e287 281

participants needed such a device to view the electronic ques-

tionnaire created through the Qualtrics platform. Second, the tablet

increased the perception of anonymity associated with the survey.

That is,participants could answer questions with the knowledge

that the research associate could notread their answers after

completion, thereby reducing social desirability bias.

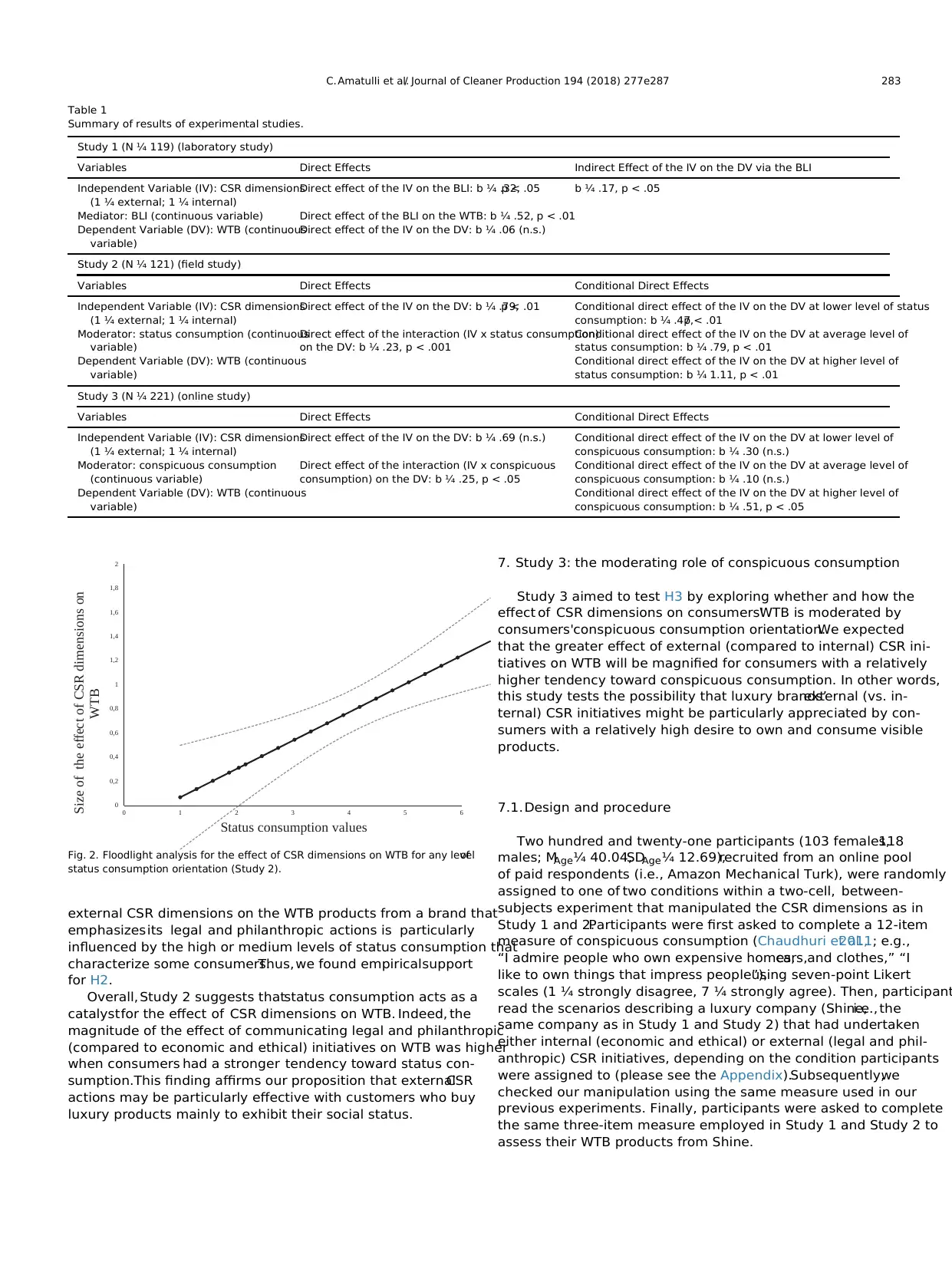

6.2. Results and discussion

Respondents in the external CSR condition perceived the luxury

brand's initiatives as more visible and observable than those in the

internal CSR condition (Mexternal¼ 5.43, SD ¼ 1.20 vs. Minternal¼ 3.17,

SD ¼ 1.10; t(119) ¼ 2.26, p < .001).

We combined the scores from the five items assessing status

consumption tendency (a ¼ 0.92)and the three items assessing

participants’WTB (a ¼ 0.93) to obtain composite measures of the

moderator and the dependent variable, respectively. We employed

the PROCESS SPSS Macro to analyze the data (Hayes,2013)dspe-

cifically utilizing Model 1 to test moderation models,in line with

H2. The status consumption measure served as the moderator in

the relationship between the CSR dimensions and WTB.

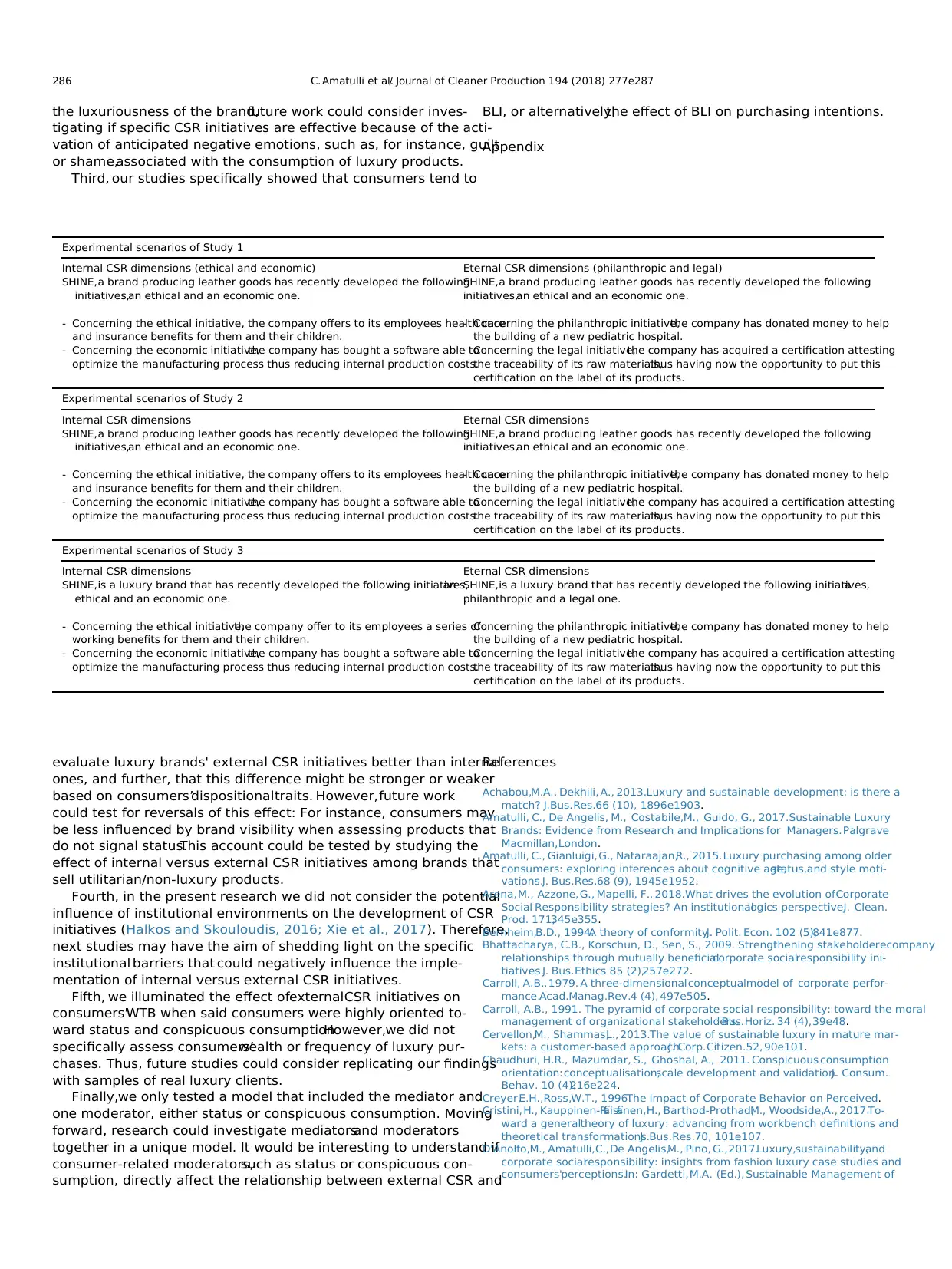

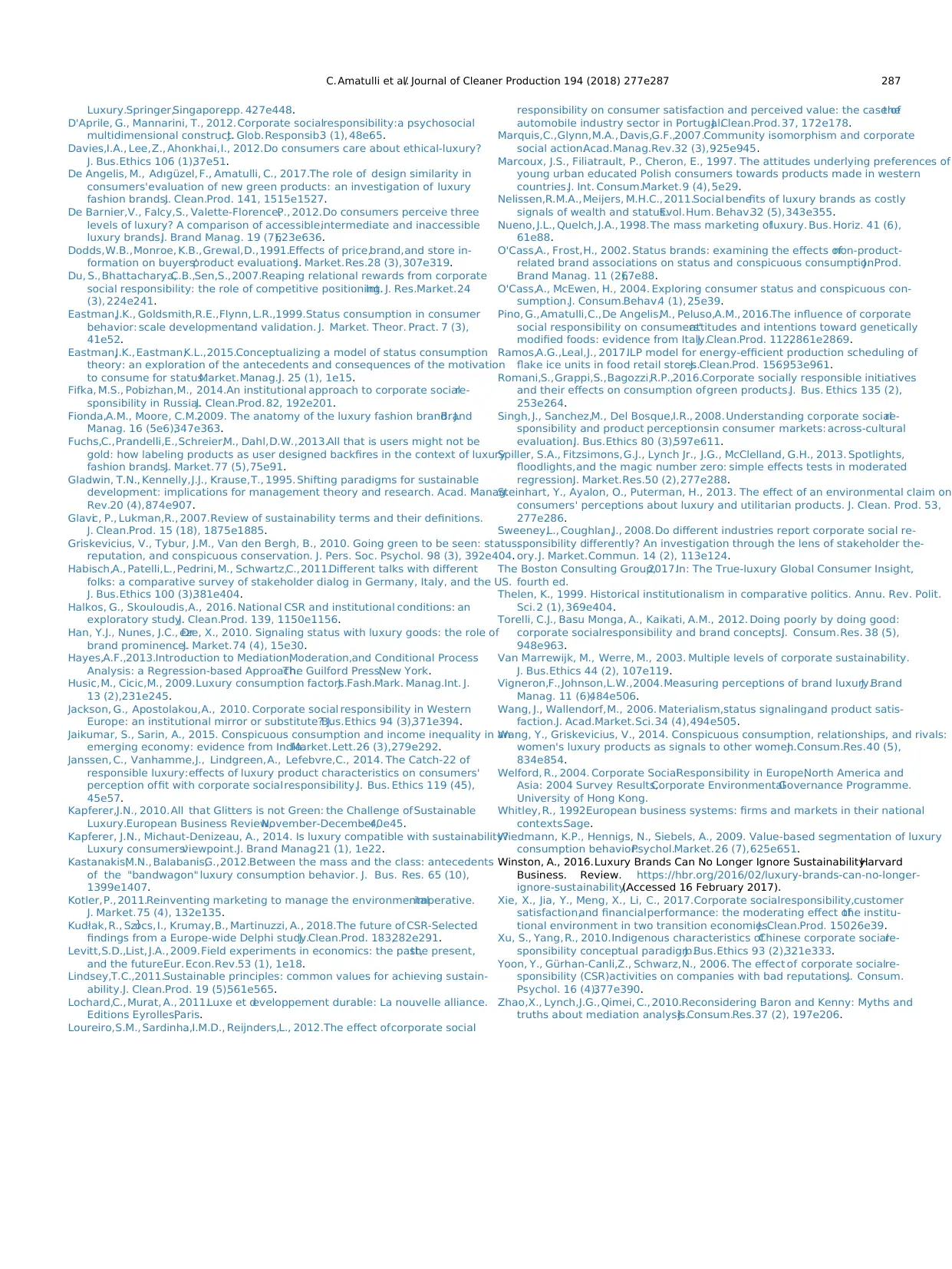

The results showed a significant and positive main effect of CSR

dimensions (coded as 1 ¼ internal and 1 ¼ external)on WTB

(b ¼ 0.79, t (118) ¼ 9.04, p < .001) and a non-significant main effect

of status consumption on WTB (b ¼ -. 07, ns). Of greater importance,

the interaction between the CSR dimensions and consumers’ status

consumption was significant (b ¼ 0.23,t(118) ¼ 3.62,p < .001; see

Fig. 1).