The Role of HRM in Driving Gender Equality in the UK Workplace

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/06

|30

|6647

|375

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the critical role of Human Resource Management (HRM) in driving gender equality within UK workplaces. It identifies key workplace issues that hinder women's career progression, including gender bias in pay, skill development, and work flexibility. The report advocates for cultural restructuring to address these issues and emphasizes the UK government's role in enforcing relevant legislation. It encourages women to embrace challenging careers, particularly in STEM fields, and highlights the need for HRM practitioners to provide career consultation and address stereotypes. The report further discusses factors contributing to gender inequality in recruitment, training, reward systems, and performance appraisals, and offers HRM strategies for mitigation, such as promoting micro-affirmations and supporting talent from the grassroots.

Running head: HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Human Resource Management

Name of the student:

Name of the university:

Author note:

Human Resource Management

Name of the student:

Name of the university:

Author note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Executive summary

The main purpose of this study is to identify how the HRM practitioners can drive workplace

equality in the United Kingdom. In course of doing so the paper identifies a number of

workplace issues, which prevent women to attain a progressive and lasting career. Some of these

issues include gender bias or discrimination in regards to pay gap, development of professional

skills and work flexibilities. The paper suggests a restructuring of culture to repair more of such

workplace issues. It also discusses the importance and role of the UK government in ensuring

that related legislations are effectively obeyed in the workplace. Moreover, the paper encourages

women to come out of their traditional frame of mind and open up towards the world of

opportunities by opting to a challenging career. Indeed, women should have their increased

interest in becoming a part of STEM fields.

Executive summary

The main purpose of this study is to identify how the HRM practitioners can drive workplace

equality in the United Kingdom. In course of doing so the paper identifies a number of

workplace issues, which prevent women to attain a progressive and lasting career. Some of these

issues include gender bias or discrimination in regards to pay gap, development of professional

skills and work flexibilities. The paper suggests a restructuring of culture to repair more of such

workplace issues. It also discusses the importance and role of the UK government in ensuring

that related legislations are effectively obeyed in the workplace. Moreover, the paper encourages

women to come out of their traditional frame of mind and open up towards the world of

opportunities by opting to a challenging career. Indeed, women should have their increased

interest in becoming a part of STEM fields.

2HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Table of Contents

1. Introduction:................................................................................................................................3

2. Why gender equality is a fundamental challenge to many researchers.......................................4

3. Recruitment and Selection:..........................................................................................................5

3.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.......................................................................5

3.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:.....................................................8

4. Training and Development:.......................................................................................................10

4.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................10

4.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................10

Case study:.................................................................................................................................11

5. Reward and Recognition/Flexible working hours:....................................................................12

5.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................12

5.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................14

6. Performance appraisal:..............................................................................................................15

6.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................15

6.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................16

Case study:.................................................................................................................................17

7. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................17

References......................................................................................................................................19

Table of Contents

1. Introduction:................................................................................................................................3

2. Why gender equality is a fundamental challenge to many researchers.......................................4

3. Recruitment and Selection:..........................................................................................................5

3.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.......................................................................5

3.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:.....................................................8

4. Training and Development:.......................................................................................................10

4.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................10

4.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................10

Case study:.................................................................................................................................11

5. Reward and Recognition/Flexible working hours:....................................................................12

5.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................12

5.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................14

6. Performance appraisal:..............................................................................................................15

6.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:.....................................................................15

6.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:...................................................16

Case study:.................................................................................................................................17

7. Conclusion.................................................................................................................................17

References......................................................................................................................................19

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

1. Introduction:

The main purpose of this study is to identify the role that HRM can play in driving

gender equality in the workplace. Employment Relations Adviser, Rachel Suff argues that the

government interventions have not been very effective in discouraging gender-based inequality

in the workplace in the United Kingdom. Rachel Suff feels that a deeper intervention by the UK

government is required to mitigate or control these challenges. Rachel Suff also feels the need

for a wider shift in organisational culture for an encouragement towards promoting genuine

gender equality (Cipd.co.uk 2019). Edmunds et al. (2016) agree to this fact and state that the

societal, and organisational contexts and cultures have an impact on women’s selection for their

careers in academic medicine.

Gender equality in the workplace is achieved when people irrespective of their gender

classification, are able to enjoy the same resources, opportunities and rewards (Wgea.gov.au

2019). However, as observed by de Vries, J.A., (2015), leadership positions are significantly

dominated by male. The leadership capability of women is somehow undermined. They are not

given sufficient amount of opportunities to help them explore their capabilities. This indicates

the existence of gender-based inequality in the workplace. Amis et al. (2018) supports the views

of de Vries, J.A., (2015) on the gender inequality issue with further emphasis on it. The author

say that gender inequality is a growing fact in many organisations and institutions. The authors

further say that some of the HRM practices are now male-biased. These include like hiring,

reward, promotion, and others. Sarvaiya and Eweje (2016) disagrees to Amis et al. (2018) and

Vries, J.A., (2015) by highlighting the importance of HRM practices in driving gender equality

in the workplace. The argument is on the basis of their observations of the data from interviews

being conducted with 29 HR and CSR professionals from large organisations in New Zealand.

1. Introduction:

The main purpose of this study is to identify the role that HRM can play in driving

gender equality in the workplace. Employment Relations Adviser, Rachel Suff argues that the

government interventions have not been very effective in discouraging gender-based inequality

in the workplace in the United Kingdom. Rachel Suff feels that a deeper intervention by the UK

government is required to mitigate or control these challenges. Rachel Suff also feels the need

for a wider shift in organisational culture for an encouragement towards promoting genuine

gender equality (Cipd.co.uk 2019). Edmunds et al. (2016) agree to this fact and state that the

societal, and organisational contexts and cultures have an impact on women’s selection for their

careers in academic medicine.

Gender equality in the workplace is achieved when people irrespective of their gender

classification, are able to enjoy the same resources, opportunities and rewards (Wgea.gov.au

2019). However, as observed by de Vries, J.A., (2015), leadership positions are significantly

dominated by male. The leadership capability of women is somehow undermined. They are not

given sufficient amount of opportunities to help them explore their capabilities. This indicates

the existence of gender-based inequality in the workplace. Amis et al. (2018) supports the views

of de Vries, J.A., (2015) on the gender inequality issue with further emphasis on it. The author

say that gender inequality is a growing fact in many organisations and institutions. The authors

further say that some of the HRM practices are now male-biased. These include like hiring,

reward, promotion, and others. Sarvaiya and Eweje (2016) disagrees to Amis et al. (2018) and

Vries, J.A., (2015) by highlighting the importance of HRM practices in driving gender equality

in the workplace. The argument is on the basis of their observations of the data from interviews

being conducted with 29 HR and CSR professionals from large organisations in New Zealand.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Sarvaiya and Eweje (2016) found that HR professionals drive equality and diversity. However,

CSR works even more than HRM and extend equality and diversity even beyond the mandatory

action.

2. Why gender equality is a fundamental challenge to many researchers

There are many complexities that define gender equality as a fundamental challenge to

many scholars. The complexities is there at the institutional, governmental, organisational as

well as at the personal level. This is indeed challenging to propose ways to drive gender equality

in the workplace. If one or two of these levels are satisfied with a set of solutions the others

might remain unsatisfied posing potential barriers to gender equality in the workplace.

For an example, the women in the United Kingdom will not be able to receive the

benefits from the strategic engagement of the European Commission for Gender Equality. It is

due to the Brexit that will prevent women from accessing these benefits. Notably, the

engagement has been allocated with €6.17 for a span of time from 2016 to 2019 (Eige.europa.eu

2019). Hence, it can be said that such political state of a country is never fruitful to both the

women and HRM practitioners. The HRM practitioners in the United Kingdom will have to take

a stand against gender inequality to be able to increase participation from the women and thereby

helping the national economy. As identified by Rhode (2017), increased women participation in

jobs especially as full-timers will boost the national economy.

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan has unveiled a new campaign “Behind every great

city”. The campaign promises to deliver on a bigger note. “City Hall” based on its first ever

gender pay audit has ensured to implement plans to reduce the gender pay gap. The campaign

will ensure that senior managers are given adequate training on how to conduct a fair recruitment

Sarvaiya and Eweje (2016) found that HR professionals drive equality and diversity. However,

CSR works even more than HRM and extend equality and diversity even beyond the mandatory

action.

2. Why gender equality is a fundamental challenge to many researchers

There are many complexities that define gender equality as a fundamental challenge to

many scholars. The complexities is there at the institutional, governmental, organisational as

well as at the personal level. This is indeed challenging to propose ways to drive gender equality

in the workplace. If one or two of these levels are satisfied with a set of solutions the others

might remain unsatisfied posing potential barriers to gender equality in the workplace.

For an example, the women in the United Kingdom will not be able to receive the

benefits from the strategic engagement of the European Commission for Gender Equality. It is

due to the Brexit that will prevent women from accessing these benefits. Notably, the

engagement has been allocated with €6.17 for a span of time from 2016 to 2019 (Eige.europa.eu

2019). Hence, it can be said that such political state of a country is never fruitful to both the

women and HRM practitioners. The HRM practitioners in the United Kingdom will have to take

a stand against gender inequality to be able to increase participation from the women and thereby

helping the national economy. As identified by Rhode (2017), increased women participation in

jobs especially as full-timers will boost the national economy.

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan has unveiled a new campaign “Behind every great

city”. The campaign promises to deliver on a bigger note. “City Hall” based on its first ever

gender pay audit has ensured to implement plans to reduce the gender pay gap. The campaign

will ensure that senior managers are given adequate training on how to conduct a fair recruitment

5HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

process. Additionally, senior managers will also be provided with mentoring as needed. There

will be an increment in few practices like increased part-time jobs and enhanced flexible working

options (Marieclaire.co.uk 2019). Indeed, this is a good move provided that there is no gender

pay gap in part-time jobs and also that there is increased aspiration for leadership positions in

women (Warren and Lyonette 2018).

González-González et al. (2018) confirm that STEM, which significantly contributes to

the United Kingdom economy has lower participation from women. The contribution could be

much stronger if more women become the part of STEM. Hence, the HRM practitioners in

STEM fields in particular should arrange and provide career consultation to women to help them

realise their job potentials and their feasibility with the industry. They need to be assured of that

STEM sectors is not just for male but for women as well. The sector needs them and they can

significantly respond to this need (Chau and Quire 2018).

3. Recruitment and Selection:

3.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:

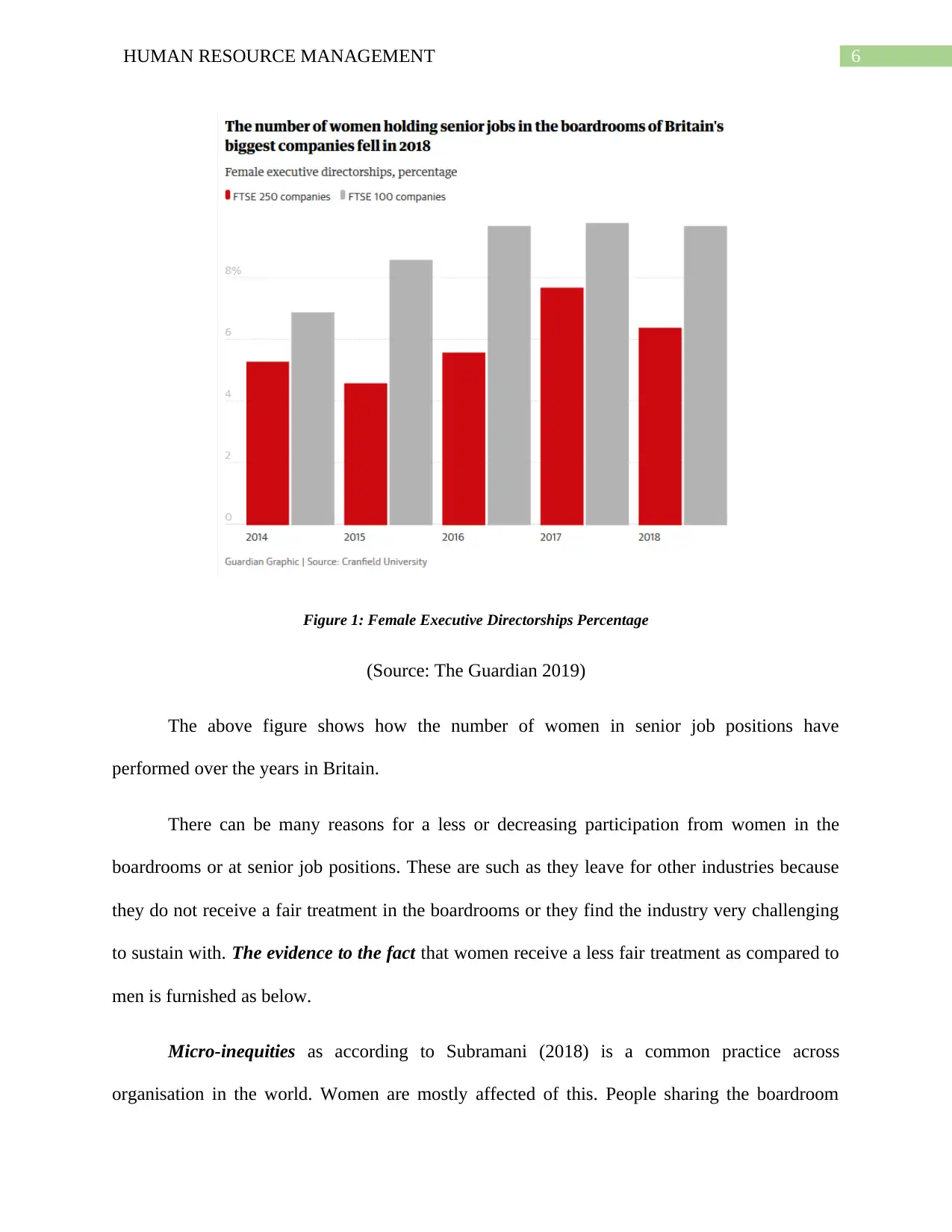

The percentage of women in the boardrooms is less as compared with men. According to

an Analysis from Cranfield University, as part of its 20th Report on FTSE Women on Boards,

highlights a falling number of women in the boardrooms (The Guardian 2019). According to the

report, there is a sharp drop in the numbers of women being the chief financial officer (CFO),

chief executive (CEO) and other executive roles on FTSE 100 companies and 250 boards (The

Guardian 2019).

process. Additionally, senior managers will also be provided with mentoring as needed. There

will be an increment in few practices like increased part-time jobs and enhanced flexible working

options (Marieclaire.co.uk 2019). Indeed, this is a good move provided that there is no gender

pay gap in part-time jobs and also that there is increased aspiration for leadership positions in

women (Warren and Lyonette 2018).

González-González et al. (2018) confirm that STEM, which significantly contributes to

the United Kingdom economy has lower participation from women. The contribution could be

much stronger if more women become the part of STEM. Hence, the HRM practitioners in

STEM fields in particular should arrange and provide career consultation to women to help them

realise their job potentials and their feasibility with the industry. They need to be assured of that

STEM sectors is not just for male but for women as well. The sector needs them and they can

significantly respond to this need (Chau and Quire 2018).

3. Recruitment and Selection:

3.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:

The percentage of women in the boardrooms is less as compared with men. According to

an Analysis from Cranfield University, as part of its 20th Report on FTSE Women on Boards,

highlights a falling number of women in the boardrooms (The Guardian 2019). According to the

report, there is a sharp drop in the numbers of women being the chief financial officer (CFO),

chief executive (CEO) and other executive roles on FTSE 100 companies and 250 boards (The

Guardian 2019).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

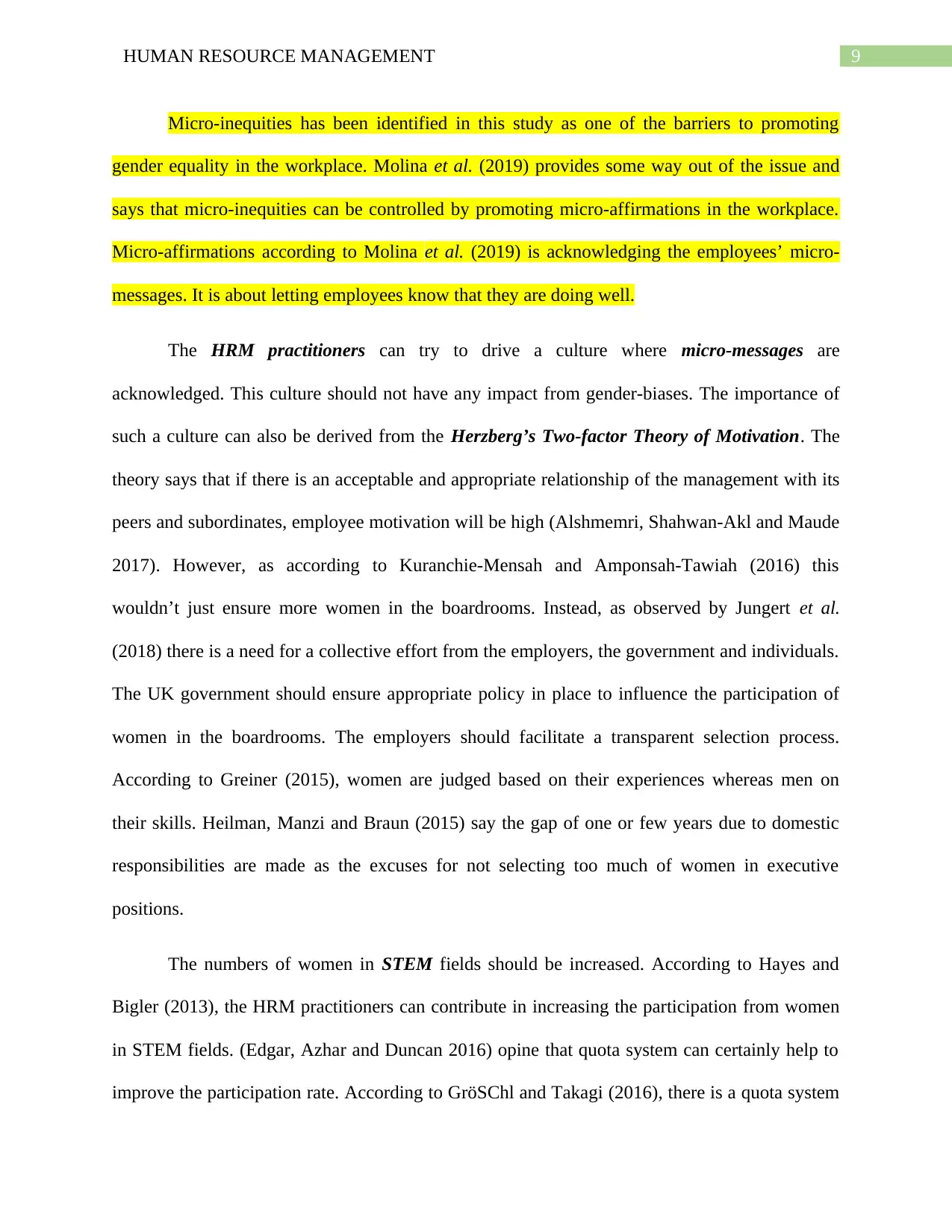

Figure 1: Female Executive Directorships Percentage

(Source: The Guardian 2019)

The above figure shows how the number of women in senior job positions have

performed over the years in Britain.

There can be many reasons for a less or decreasing participation from women in the

boardrooms or at senior job positions. These are such as they leave for other industries because

they do not receive a fair treatment in the boardrooms or they find the industry very challenging

to sustain with. The evidence to the fact that women receive a less fair treatment as compared to

men is furnished as below.

Micro-inequities as according to Subramani (2018) is a common practice across

organisation in the world. Women are mostly affected of this. People sharing the boardroom

Figure 1: Female Executive Directorships Percentage

(Source: The Guardian 2019)

The above figure shows how the number of women in senior job positions have

performed over the years in Britain.

There can be many reasons for a less or decreasing participation from women in the

boardrooms or at senior job positions. These are such as they leave for other industries because

they do not receive a fair treatment in the boardrooms or they find the industry very challenging

to sustain with. The evidence to the fact that women receive a less fair treatment as compared to

men is furnished as below.

Micro-inequities as according to Subramani (2018) is a common practice across

organisation in the world. Women are mostly affected of this. People sharing the boardroom

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

usually have gender biases for women inherited in them. As a consequences of such biases, they

tend to overlook or ignore the input from one or few of the women. Such an act can be the result

of several facts. According to Ambler (2016), few managers have perceptions that women cannot

be a better decision-maker due to many distractions they have in their lives. For an example, they

are considered as the only most responsible person in a family to take care of their kids. They

also need to take care of many other domestic works like cooking. Secules et al. (2018) support

the views of Subramani (2018) and say that it is generally very difficult to pretend whether

micro-inequity is intentionally being given a place in the workplace. It appears that the HRM

practitioners have tough task ahead of them in the form of low number of women in the

boardrooms and at higher leadership position.

The fact that a significant number of women are less likely to stay in STEM fields is

being discussed in this paragraph. Wang and Degol (2017) identified few professions such as

STEM where women are underrepresented. The authors produced six explanations to women’s

underrepresentation in STEM fields. These are cognitive ability, occupational interests or

preferences, relative cognitive strengths, field-specific ability beliefs, gender-based biases and

stereotypes, and work-family balance and lifestyle values preferences. Surprisingly, women

make up 14.4% of all those working in STEM fields in the United Kingdom (The Guardian

2019). This is despite a fact that Women represent half of the entire workforce in the STEM

fields (The Guardian 2019). If the percentage of women increases in STEM this will help to

increase the labour value in the United Kingdom by at least £2bn (The Guardian 2019). Women

certainly are less likely to enter and more likely to leave it for other industries. The rate of

women who started their business career in tech-intensive industries and leaving for other

industries is equal to 53% (Catalyst.org 2019). Additionally, women on boards in the information

usually have gender biases for women inherited in them. As a consequences of such biases, they

tend to overlook or ignore the input from one or few of the women. Such an act can be the result

of several facts. According to Ambler (2016), few managers have perceptions that women cannot

be a better decision-maker due to many distractions they have in their lives. For an example, they

are considered as the only most responsible person in a family to take care of their kids. They

also need to take care of many other domestic works like cooking. Secules et al. (2018) support

the views of Subramani (2018) and say that it is generally very difficult to pretend whether

micro-inequity is intentionally being given a place in the workplace. It appears that the HRM

practitioners have tough task ahead of them in the form of low number of women in the

boardrooms and at higher leadership position.

The fact that a significant number of women are less likely to stay in STEM fields is

being discussed in this paragraph. Wang and Degol (2017) identified few professions such as

STEM where women are underrepresented. The authors produced six explanations to women’s

underrepresentation in STEM fields. These are cognitive ability, occupational interests or

preferences, relative cognitive strengths, field-specific ability beliefs, gender-based biases and

stereotypes, and work-family balance and lifestyle values preferences. Surprisingly, women

make up 14.4% of all those working in STEM fields in the United Kingdom (The Guardian

2019). This is despite a fact that Women represent half of the entire workforce in the STEM

fields (The Guardian 2019). If the percentage of women increases in STEM this will help to

increase the labour value in the United Kingdom by at least £2bn (The Guardian 2019). Women

certainly are less likely to enter and more likely to leave it for other industries. The rate of

women who started their business career in tech-intensive industries and leaving for other

industries is equal to 53% (Catalyst.org 2019). Additionally, women on boards in the information

8HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

technology industry as of 2015 is equal to 12.2%, which is comparatively less than for many

other industries like Financials (16.9%) and Consumer staples (17.4%) (Catalyst.org 2019).

There is a lack of transparency in the recruitment process as evidenced in a fact that

women are more preferred for non-executive positions (Makarova, Aeschlimann and Herzog

2016). However, the lack of transparency may be the consequences of few factors that compel

recruiters to behave unintentionally in a different manner. As stated by Slaughter (2015), men are

more superior to women in some regards like the tendency to win. According to the author, this

is one of the reasons why men are more dominating than women and seek the leadership roles.

This is also evidenced in how they represent them while being in the interview or in the

workplace. Recruitment as according to Riley, Michael and Mahoney (2017) is a process to

create assets to a company. By recruiting men for the executive positions they perceive as they

are creating leaders for the company.

To promote a true gender equality a quota system for the boardrooms, which presently

exists. Indeed, (Smith et al. 2015) feel a need to support and nurture talent from the grassroots.

This will ensure that talent pools are comprising of diverse people. As stated by Barak (2016),

senior management should vocally support the gender diversity. As opined by Chappell and

Waylen (2013), some legal barriers prevent the appointment of women on boards based on

gender only. For an example, the 2010 Equality Act allows a positive discrimination based on

the genders if both are equally deserving and there is an under-representation of a particular

gender in the workforce (The Guardian 2019).

3.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:

technology industry as of 2015 is equal to 12.2%, which is comparatively less than for many

other industries like Financials (16.9%) and Consumer staples (17.4%) (Catalyst.org 2019).

There is a lack of transparency in the recruitment process as evidenced in a fact that

women are more preferred for non-executive positions (Makarova, Aeschlimann and Herzog

2016). However, the lack of transparency may be the consequences of few factors that compel

recruiters to behave unintentionally in a different manner. As stated by Slaughter (2015), men are

more superior to women in some regards like the tendency to win. According to the author, this

is one of the reasons why men are more dominating than women and seek the leadership roles.

This is also evidenced in how they represent them while being in the interview or in the

workplace. Recruitment as according to Riley, Michael and Mahoney (2017) is a process to

create assets to a company. By recruiting men for the executive positions they perceive as they

are creating leaders for the company.

To promote a true gender equality a quota system for the boardrooms, which presently

exists. Indeed, (Smith et al. 2015) feel a need to support and nurture talent from the grassroots.

This will ensure that talent pools are comprising of diverse people. As stated by Barak (2016),

senior management should vocally support the gender diversity. As opined by Chappell and

Waylen (2013), some legal barriers prevent the appointment of women on boards based on

gender only. For an example, the 2010 Equality Act allows a positive discrimination based on

the genders if both are equally deserving and there is an under-representation of a particular

gender in the workforce (The Guardian 2019).

3.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Micro-inequities has been identified in this study as one of the barriers to promoting

gender equality in the workplace. Molina et al. (2019) provides some way out of the issue and

says that micro-inequities can be controlled by promoting micro-affirmations in the workplace.

Micro-affirmations according to Molina et al. (2019) is acknowledging the employees’ micro-

messages. It is about letting employees know that they are doing well.

The HRM practitioners can try to drive a culture where micro-messages are

acknowledged. This culture should not have any impact from gender-biases. The importance of

such a culture can also be derived from the Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory of Motivation. The

theory says that if there is an acceptable and appropriate relationship of the management with its

peers and subordinates, employee motivation will be high (Alshmemri, Shahwan-Akl and Maude

2017). However, as according to Kuranchie-Mensah and Amponsah-Tawiah (2016) this

wouldn’t just ensure more women in the boardrooms. Instead, as observed by Jungert et al.

(2018) there is a need for a collective effort from the employers, the government and individuals.

The UK government should ensure appropriate policy in place to influence the participation of

women in the boardrooms. The employers should facilitate a transparent selection process.

According to Greiner (2015), women are judged based on their experiences whereas men on

their skills. Heilman, Manzi and Braun (2015) say the gap of one or few years due to domestic

responsibilities are made as the excuses for not selecting too much of women in executive

positions.

The numbers of women in STEM fields should be increased. According to Hayes and

Bigler (2013), the HRM practitioners can contribute in increasing the participation from women

in STEM fields. (Edgar, Azhar and Duncan 2016) opine that quota system can certainly help to

improve the participation rate. According to GröSChl and Takagi (2016), there is a quota system

Micro-inequities has been identified in this study as one of the barriers to promoting

gender equality in the workplace. Molina et al. (2019) provides some way out of the issue and

says that micro-inequities can be controlled by promoting micro-affirmations in the workplace.

Micro-affirmations according to Molina et al. (2019) is acknowledging the employees’ micro-

messages. It is about letting employees know that they are doing well.

The HRM practitioners can try to drive a culture where micro-messages are

acknowledged. This culture should not have any impact from gender-biases. The importance of

such a culture can also be derived from the Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory of Motivation. The

theory says that if there is an acceptable and appropriate relationship of the management with its

peers and subordinates, employee motivation will be high (Alshmemri, Shahwan-Akl and Maude

2017). However, as according to Kuranchie-Mensah and Amponsah-Tawiah (2016) this

wouldn’t just ensure more women in the boardrooms. Instead, as observed by Jungert et al.

(2018) there is a need for a collective effort from the employers, the government and individuals.

The UK government should ensure appropriate policy in place to influence the participation of

women in the boardrooms. The employers should facilitate a transparent selection process.

According to Greiner (2015), women are judged based on their experiences whereas men on

their skills. Heilman, Manzi and Braun (2015) say the gap of one or few years due to domestic

responsibilities are made as the excuses for not selecting too much of women in executive

positions.

The numbers of women in STEM fields should be increased. According to Hayes and

Bigler (2013), the HRM practitioners can contribute in increasing the participation from women

in STEM fields. (Edgar, Azhar and Duncan 2016) opine that quota system can certainly help to

improve the participation rate. According to GröSChl and Takagi (2016), there is a quota system

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

in Norway that allows 40% of women in the boardrooms. Lebanon as found by Barak (2016) has

quota system based on religious beliefs. In a similar ways Chidiac (2018) believes that quota

system should influence the women’s participation rate in the boardrooms.

4. Training and Development:

4.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:

According to Pingleton et al. (2016), leadership development opportunities provided to

women is not the same as it is to men. As opined by Gipson et al. (2017), leadership gender gap

matters as gender-balanced teams of leaders significantly impact the business results. Burton and

Weiner (2016) reports that development pipeline in the organisations needs a revisit as the higher

positions in a hierarchy is more often filled by men. The authors further say that the numbers of

men are higher in rating the training for leadership development as successful. As observed by

Schachter (2017), special training on strategic thinking and negotiation is given more to men

than women. As admitted by Kitada, Williams and Froholdt (2015) leadership performance was

found as much superior in those who receive training on negotiation skills. Rhode (2017) points

out that women have least access to leadership training especially in male-dominated fields such

as STEM.

4.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:

The HRM practitioners can play a significant role in enhancing the access to leadership

training for women. According to Helitzer et al. (2016), the HRM personnel can encourage

managers to extend their support towards women in form of accessing to leadership training.

Seo, Huang and Han (2017) suggest that the HRM personnel should propose this idea with its

expected positive outcomes. The list of expected benefits should include how women in the

in Norway that allows 40% of women in the boardrooms. Lebanon as found by Barak (2016) has

quota system based on religious beliefs. In a similar ways Chidiac (2018) believes that quota

system should influence the women’s participation rate in the boardrooms.

4. Training and Development:

4.1 Factors contributing to the gender inequality:

According to Pingleton et al. (2016), leadership development opportunities provided to

women is not the same as it is to men. As opined by Gipson et al. (2017), leadership gender gap

matters as gender-balanced teams of leaders significantly impact the business results. Burton and

Weiner (2016) reports that development pipeline in the organisations needs a revisit as the higher

positions in a hierarchy is more often filled by men. The authors further say that the numbers of

men are higher in rating the training for leadership development as successful. As observed by

Schachter (2017), special training on strategic thinking and negotiation is given more to men

than women. As admitted by Kitada, Williams and Froholdt (2015) leadership performance was

found as much superior in those who receive training on negotiation skills. Rhode (2017) points

out that women have least access to leadership training especially in male-dominated fields such

as STEM.

4.2 The role of the HRM in mitigating the factors identified:

The HRM practitioners can play a significant role in enhancing the access to leadership

training for women. According to Helitzer et al. (2016), the HRM personnel can encourage

managers to extend their support towards women in form of accessing to leadership training.

Seo, Huang and Han (2017) suggest that the HRM personnel should propose this idea with its

expected positive outcomes. The list of expected benefits should include how women in the

11HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

leadership position can impact the company’s productivity. According to Brue and Brue (2016),

numerous business case studies have found a higher representation of women as the

manufacturing leaders. A meta-analysis of studies being conducted in the 1990s highlights that

the financial performance of a firm increases when more women are in the leadership roles

(IndustryWeek 2019). This is truer when women are the CEOs. Solaja, Idowu and James (2016)

opine that having more women in the boardrooms increases the earnings and sales.

Davis and Maldonado (2015) suggest the HRM personnel to be strategic while selecting

the modalities to support the multi-modal programs. This is to ensure that training is facilitated

and delivered in a way that it is equally benefitting and full of opportunities for both men and

women. Debebe et al. (2016) identify formal coaching especially tailored to meet the women’s

needs as an effective way to encourage women participation in the boardrooms. Pingleton et al.

(2016) feel the necessity to have performance measuring indicators to report on and measure the

outcomes of the coaching for both men and women. Women should be taught the target specific

skills to help them access to leadership-based training.

Case study:

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), Canada:

The human resources personnel are committed to increase the number of women

Sciences and Engineering sector. To support the process they are offering career opportunities to

women along with it accommodating the women’s responsibility towards their family. Programs

are designed to ensure fair treatment with all applicants irrespective of the gender. NSERC

identify that attracting women more towards this industry is a major challenge. To deal with it

they will identify barriers impacting women’s participation in this industry (Jsps.go.jp 2019).

leadership position can impact the company’s productivity. According to Brue and Brue (2016),

numerous business case studies have found a higher representation of women as the

manufacturing leaders. A meta-analysis of studies being conducted in the 1990s highlights that

the financial performance of a firm increases when more women are in the leadership roles

(IndustryWeek 2019). This is truer when women are the CEOs. Solaja, Idowu and James (2016)

opine that having more women in the boardrooms increases the earnings and sales.

Davis and Maldonado (2015) suggest the HRM personnel to be strategic while selecting

the modalities to support the multi-modal programs. This is to ensure that training is facilitated

and delivered in a way that it is equally benefitting and full of opportunities for both men and

women. Debebe et al. (2016) identify formal coaching especially tailored to meet the women’s

needs as an effective way to encourage women participation in the boardrooms. Pingleton et al.

(2016) feel the necessity to have performance measuring indicators to report on and measure the

outcomes of the coaching for both men and women. Women should be taught the target specific

skills to help them access to leadership-based training.

Case study:

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), Canada:

The human resources personnel are committed to increase the number of women

Sciences and Engineering sector. To support the process they are offering career opportunities to

women along with it accommodating the women’s responsibility towards their family. Programs

are designed to ensure fair treatment with all applicants irrespective of the gender. NSERC

identify that attracting women more towards this industry is a major challenge. To deal with it

they will identify barriers impacting women’s participation in this industry (Jsps.go.jp 2019).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 30

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.