Capstone Project: Surgical Site Infection Identification in Healthcare

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/06

|20

|2269

|165

Project

AI Summary

This capstone project addresses the critical issue of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) in healthcare settings. The project begins with a background on SSIs, emphasizing their impact on patient outcomes and healthcare costs, and presents a problem statement focused on reducing SSI rates before and after clinical operations. The purpose of the change proposal is to investigate the effectiveness of preoperative bathing with antiseptic soaps. A PICOT question is formulated to guide the research, comparing chlorhexidine baths to regular soap and water. The project employs an annotated bibliography to evaluate eight relevant articles, analyzing research questions, methods, and findings. It also discusses applicable change theories and proposes an implementation plan, including outcome measures and potential barriers. Recommendations for overcoming these barriers and evidence of revision are provided, with a focus on promoting evidence-based approaches to SSI prevention, such as the use of chlorhexidine soaps.

Running Head: Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

IDENTIFICATION OF SURGICAL SITE INFECTION IN

HEALTHCARE SETTINGS

IDENTIFICATION OF SURGICAL SITE INFECTION IN

HEALTHCARE SETTINGS

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Background

In the modern healthcare setting, the phrase ‘Surgical Site Infection’ covers a vast area of

consideration. According to the statement of clinical experts, Surgical Site Infection or SSI is one

of the most common issues in the clinical surgery process. It is considered as it retains a direct

connection with the financial burden, service quality reduction, and patient mortality. As per the

report of Webster & Osborne (2015), SSI generally occurs in the areas where the surgeries have

taken place. Unfortunately, the occurrence of SSI in modern healthcare settings is still prevalent.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the interventional requirement for SSI prevention is higher in

modern healthcare settings. Based on such a situation, the assignment is done for addressing the

effects of SSI on patients’ and service providers’ health, for developing some strategic plans to

prevent or reduce the surgical site infection.

Problem statement

The main problem statement, based on which the research study conducted, is to lower

the number of surgical site infection before and after the clinical operations. It is evident that

patients or care providers often use plain soaps for showering, bathing, or washing body parts,

after the surgical process. Now, the main question is to investigate the differences in antiseptic

soaps and plain soaps and their roles in preventing surgical site infection as well.

Purpose of the change proposal

The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of preoperative bathing along with

antiseptic soaps, which is one of the most common pathways of SSI prevention. Apart from this,

the differentiated impacts of antiseptic soaps and plain soaps on the areas of surgical site

infection are also a central part of the change proposal. In order to highlight the consequences

and to identify the possible changes, the researcher(s) has structured the following PICOT

question for specification of the issue.

Background

In the modern healthcare setting, the phrase ‘Surgical Site Infection’ covers a vast area of

consideration. According to the statement of clinical experts, Surgical Site Infection or SSI is one

of the most common issues in the clinical surgery process. It is considered as it retains a direct

connection with the financial burden, service quality reduction, and patient mortality. As per the

report of Webster & Osborne (2015), SSI generally occurs in the areas where the surgeries have

taken place. Unfortunately, the occurrence of SSI in modern healthcare settings is still prevalent.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the interventional requirement for SSI prevention is higher in

modern healthcare settings. Based on such a situation, the assignment is done for addressing the

effects of SSI on patients’ and service providers’ health, for developing some strategic plans to

prevent or reduce the surgical site infection.

Problem statement

The main problem statement, based on which the research study conducted, is to lower

the number of surgical site infection before and after the clinical operations. It is evident that

patients or care providers often use plain soaps for showering, bathing, or washing body parts,

after the surgical process. Now, the main question is to investigate the differences in antiseptic

soaps and plain soaps and their roles in preventing surgical site infection as well.

Purpose of the change proposal

The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of preoperative bathing along with

antiseptic soaps, which is one of the most common pathways of SSI prevention. Apart from this,

the differentiated impacts of antiseptic soaps and plain soaps on the areas of surgical site

infection are also a central part of the change proposal. In order to highlight the consequences

and to identify the possible changes, the researcher(s) has structured the following PICOT

question for specification of the issue.

3Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

PICOT

In preoperative patients (P), how effective are chlorhexidine baths (I) compared to

regular soap and water baths (C), in controlling the number of surgical site infections (O)

during the preoperative and recovery period after surgery (T)?

Literature search strategy employed

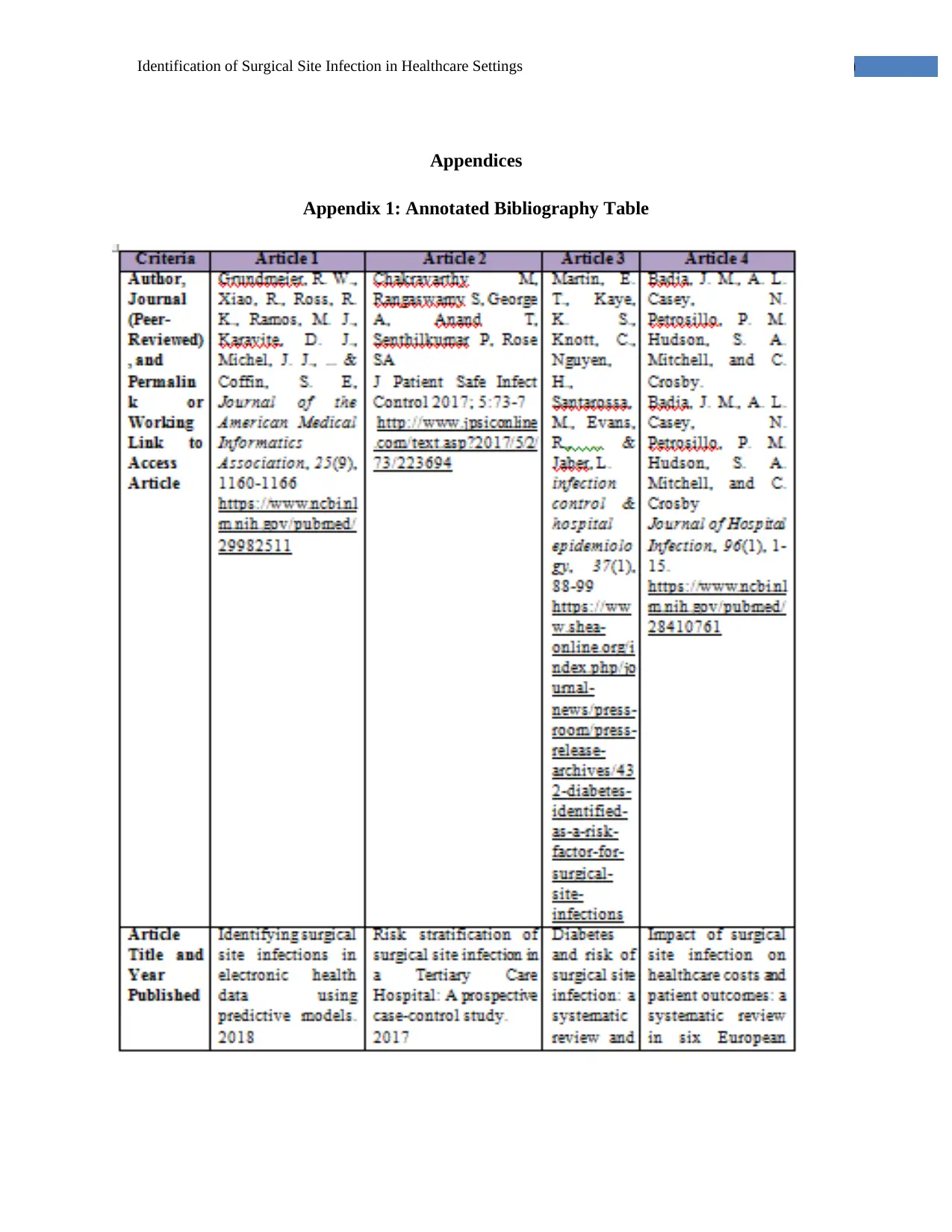

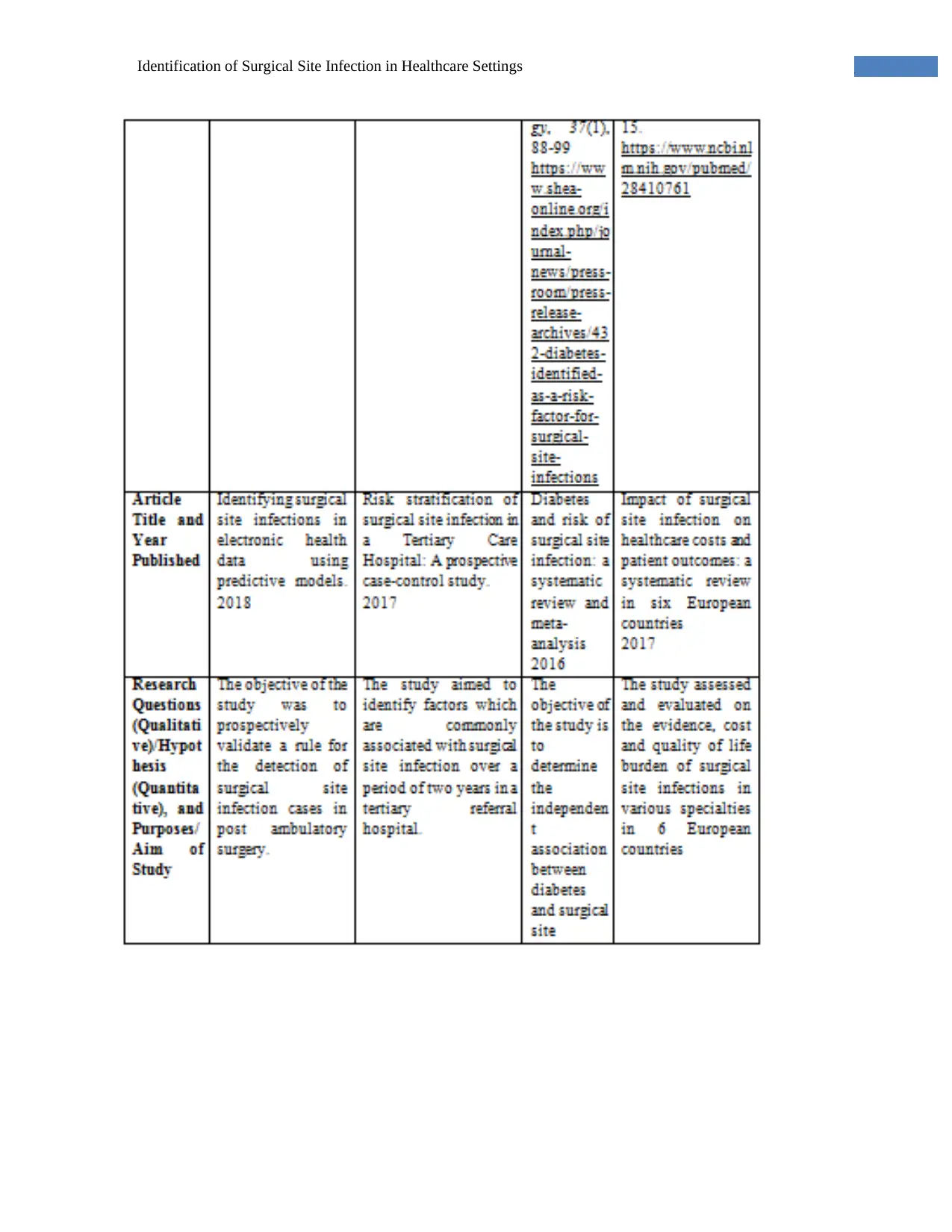

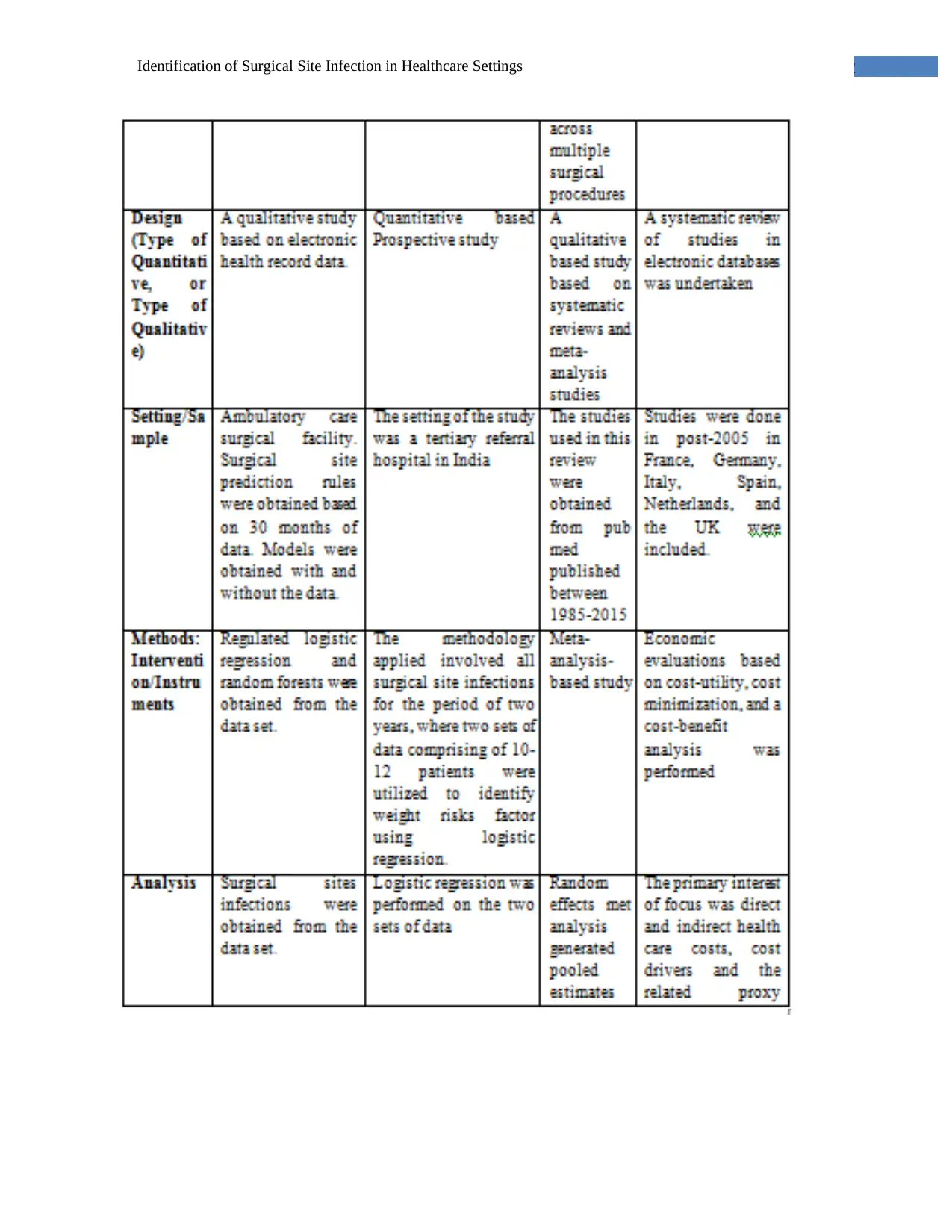

In order to evaluate the literature investigated on the topic of SSI in current healthcare

settings, the researcher(s) has applied an annotated bibliography structure. The literature

searched by the researcher(s) has been obtained from different online databases. Based on some

inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher(s) has chosen total eight articles, which are

relevant with the selected topic, and include specific research paper structure, e.g. research

questions, research methods, design, samples, interventions, analysis, key findings, and

recommendation parts. The brief table of the annotated bibliography is attached in the Appendix

section.

Evaluation of the literature

The chosen eight articles provide critical or argumentative supports to the developed

PICOT question from different viewpoints. Such as the study conducted by Grundmeier, Xiao,

Ross, Ramos, Karavite, Michel, and Coffin (2018), to identify the presence of SSI, clinicians

could apply EHR technology, as it is efficient in detecting ambulatory surgical infection. A study

conducted by Chakravarthy, Rangaswamy, George, Anand, Senthilkumar & Rose (2017)

includes research questions represents the process of SSI factor determination, which supports

the developed PICOT statement, as based on the identified factors, researcher(s) could create SSI

prevention strategies.

The researcher(s) has also performed comparison and evaluation of the sample

population, research limitation, conclusion, and recommendation parts along with research

questions. For example, Martin, Kaye, Knott, Nguyen, Santarossa, Evans, Elizabeth, and Jaber

(2015) included total 94 peer-reviewed journals whereas Kunutsor, Whitehouse, Blom, and

Beswick (2017) included total nine peer-reviewed journals as the sample population for this

research paper. However, the articles also retain certain types of limitations, such as Badia,

Casey, Petrosillo, Hudson, Mitchell & Crosby (2017) used samples from six countries, which is

PICOT

In preoperative patients (P), how effective are chlorhexidine baths (I) compared to

regular soap and water baths (C), in controlling the number of surgical site infections (O)

during the preoperative and recovery period after surgery (T)?

Literature search strategy employed

In order to evaluate the literature investigated on the topic of SSI in current healthcare

settings, the researcher(s) has applied an annotated bibliography structure. The literature

searched by the researcher(s) has been obtained from different online databases. Based on some

inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher(s) has chosen total eight articles, which are

relevant with the selected topic, and include specific research paper structure, e.g. research

questions, research methods, design, samples, interventions, analysis, key findings, and

recommendation parts. The brief table of the annotated bibliography is attached in the Appendix

section.

Evaluation of the literature

The chosen eight articles provide critical or argumentative supports to the developed

PICOT question from different viewpoints. Such as the study conducted by Grundmeier, Xiao,

Ross, Ramos, Karavite, Michel, and Coffin (2018), to identify the presence of SSI, clinicians

could apply EHR technology, as it is efficient in detecting ambulatory surgical infection. A study

conducted by Chakravarthy, Rangaswamy, George, Anand, Senthilkumar & Rose (2017)

includes research questions represents the process of SSI factor determination, which supports

the developed PICOT statement, as based on the identified factors, researcher(s) could create SSI

prevention strategies.

The researcher(s) has also performed comparison and evaluation of the sample

population, research limitation, conclusion, and recommendation parts along with research

questions. For example, Martin, Kaye, Knott, Nguyen, Santarossa, Evans, Elizabeth, and Jaber

(2015) included total 94 peer-reviewed journals whereas Kunutsor, Whitehouse, Blom, and

Beswick (2017) included total nine peer-reviewed journals as the sample population for this

research paper. However, the articles also retain certain types of limitations, such as Badia,

Casey, Petrosillo, Hudson, Mitchell & Crosby (2017) used samples from six countries, which is

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

comparatively larger for the capstone research project. At the last part, all the studies reflect a

number of solutions regarding the reduction of SSI in modern healthcare organisations.

Applicable change or nursing theory utilise

The chosen journals or articles provide evidence for understanding the process by which

clinical experts could change the occurrence of SSI in healthcare settings. As mentioned in the

earlier part, Grundmeier, Xiao, Ross, Ramos, Karavite, Michel, and Coffin (2018) mentioned

about the EHR technology implementation, which is efficient in case of evaluating the number of

SSI in a specific surgical unit. Mueck & Kao (2017) reflects that nurses could integrate the SSI

assessment protocol for identifying the post-discharge risks associated with post-surgical

patients. Chakravarthy, Rangaswamy, George, Anand, Senthilkumar & Rose (2017) mentioned

that nurses and other caregivers could develop SSI prevention plans based on some internal and

external factors, such as Body Mass Index, Antiseptic shower, and so on.

According to the statement of Allegranzi, Bischoff & de Jonge (2016), the most basic

evidence-based solution of this SSI is the application of CHG or Chlorhexidine Gluconate, which

is one of the traditional and significant antiseptic components. The safe agent acts against a range

of microorganisms, including gram-positive, non-spore-forming, and gram-negative yeast,

bacteria, and viruses. However, based on the sensitivity of human skin, clinicians suggest

application of CHG by 2-3 times separated applications. The first one would be done a night

before surgery, the second would be in the morning, and the final one would be just before going

to the operation room.

Therefore, through summarising the evidence gathered from the chosen articles and other

resources, the changes required for preventing SSI are as follows-

Application of Prophylactic Antibiotics through an appropriate manner

Avoiding functioning on the operative sites or the sensitive post-operative sites

Implementation of fundamental prevention strategies developed by CDC, such as

preventing consumption of tobacco, applying sterile antiseptic materials, showering by

CHG or other antiseptic soaps, using Personal Protective Equipment, and so on (Changes

to Prevent Surgical Site Infection, 2018)

comparatively larger for the capstone research project. At the last part, all the studies reflect a

number of solutions regarding the reduction of SSI in modern healthcare organisations.

Applicable change or nursing theory utilise

The chosen journals or articles provide evidence for understanding the process by which

clinical experts could change the occurrence of SSI in healthcare settings. As mentioned in the

earlier part, Grundmeier, Xiao, Ross, Ramos, Karavite, Michel, and Coffin (2018) mentioned

about the EHR technology implementation, which is efficient in case of evaluating the number of

SSI in a specific surgical unit. Mueck & Kao (2017) reflects that nurses could integrate the SSI

assessment protocol for identifying the post-discharge risks associated with post-surgical

patients. Chakravarthy, Rangaswamy, George, Anand, Senthilkumar & Rose (2017) mentioned

that nurses and other caregivers could develop SSI prevention plans based on some internal and

external factors, such as Body Mass Index, Antiseptic shower, and so on.

According to the statement of Allegranzi, Bischoff & de Jonge (2016), the most basic

evidence-based solution of this SSI is the application of CHG or Chlorhexidine Gluconate, which

is one of the traditional and significant antiseptic components. The safe agent acts against a range

of microorganisms, including gram-positive, non-spore-forming, and gram-negative yeast,

bacteria, and viruses. However, based on the sensitivity of human skin, clinicians suggest

application of CHG by 2-3 times separated applications. The first one would be done a night

before surgery, the second would be in the morning, and the final one would be just before going

to the operation room.

Therefore, through summarising the evidence gathered from the chosen articles and other

resources, the changes required for preventing SSI are as follows-

Application of Prophylactic Antibiotics through an appropriate manner

Avoiding functioning on the operative sites or the sensitive post-operative sites

Implementation of fundamental prevention strategies developed by CDC, such as

preventing consumption of tobacco, applying sterile antiseptic materials, showering by

CHG or other antiseptic soaps, using Personal Protective Equipment, and so on (Changes

to Prevent Surgical Site Infection, 2018)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Proposed implementation plan with outcome measures

Nurses would use their intervention plans for supporting patients during the application

of CHG antiseptic soaps. The first step of applying this soap is to assess the sensitivity of

patients’ skin to CHG. During the assessment, nurses would also provide suggestions about the

process of soap application in the pre-operative areas and the number of application required

before surgery. On the other hand, Kang, Holekamp, Wagner & Lehman (2015) stated that it is

also necessary to evaluate the skin hypersensitivity standards, for avoiding any other skin

complications. Nurses would also provide attention on the time of baths taken by the patients, the

time of bathing completion, and the presence of any irritation or sensitivity standards.

The implication of SSI prevention techniques is required to prioritise during the post-

operative wound-care management system. Nurses and other caregivers need to provide attention

to the PACU or Post Anaesthesia Care Unit, for checking the dressing materials. Apart from this,

maintenance of hand hygiene standards would be a prominent part of SSI prevention, along with

stronger asepsis protocols. As stated by Leaper & Ousey (2015), nurses would focus on

delivering all the relevant and required information to the patients about the post-operative

system and SSI consequences, along with specifying the practical process of eliminating the

possibilities of surgical hazards. Application of 2-4% of the CHG soaps is determined as safe and

effective for the prevention of surgical site infection.

Identification of potential barriers to planning implementation and recommendation for

overcoming

Although, prevention of SSI is essential in the current clinical settings, however,

clinicians often explore different internal or external barriers while implementing the prevention

plans in the existing operational environments. For example, nurses often face obstacles in

applying SSI prevention tools and techniques as they have insufficient knowledge about the

topic. On the other hand, patients often could not receive proper information from the clinical

experts; therefore, they feel afraid of using such antiseptic soaps and other elements. For

overcoming these barriers, Chen, Song, Chen, Lin & Zhang (2016) suggested that

implementation of SSI prevention techniques in the training and education programs would be

helpful for the healthcare providers. They would understand the significance of SSI prevention

techniques, tools, and processes, and deliver proficient information to the patients. This would

Proposed implementation plan with outcome measures

Nurses would use their intervention plans for supporting patients during the application

of CHG antiseptic soaps. The first step of applying this soap is to assess the sensitivity of

patients’ skin to CHG. During the assessment, nurses would also provide suggestions about the

process of soap application in the pre-operative areas and the number of application required

before surgery. On the other hand, Kang, Holekamp, Wagner & Lehman (2015) stated that it is

also necessary to evaluate the skin hypersensitivity standards, for avoiding any other skin

complications. Nurses would also provide attention on the time of baths taken by the patients, the

time of bathing completion, and the presence of any irritation or sensitivity standards.

The implication of SSI prevention techniques is required to prioritise during the post-

operative wound-care management system. Nurses and other caregivers need to provide attention

to the PACU or Post Anaesthesia Care Unit, for checking the dressing materials. Apart from this,

maintenance of hand hygiene standards would be a prominent part of SSI prevention, along with

stronger asepsis protocols. As stated by Leaper & Ousey (2015), nurses would focus on

delivering all the relevant and required information to the patients about the post-operative

system and SSI consequences, along with specifying the practical process of eliminating the

possibilities of surgical hazards. Application of 2-4% of the CHG soaps is determined as safe and

effective for the prevention of surgical site infection.

Identification of potential barriers to planning implementation and recommendation for

overcoming

Although, prevention of SSI is essential in the current clinical settings, however,

clinicians often explore different internal or external barriers while implementing the prevention

plans in the existing operational environments. For example, nurses often face obstacles in

applying SSI prevention tools and techniques as they have insufficient knowledge about the

topic. On the other hand, patients often could not receive proper information from the clinical

experts; therefore, they feel afraid of using such antiseptic soaps and other elements. For

overcoming these barriers, Chen, Song, Chen, Lin & Zhang (2016) suggested that

implementation of SSI prevention techniques in the training and education programs would be

helpful for the healthcare providers. They would understand the significance of SSI prevention

techniques, tools, and processes, and deliver proficient information to the patients. This would

6Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

help in improving the entire public health outcomes by lowering the mortality or morbidity rate

associated with the surgical site infection.

Evidence of Revision

Since the prevalence of SSI is highly expanded in the current healthcare settings,

therefore, evidence for revision can be obtained from different government and institutional

websites. As per the evidence of WHO, for omitting the possibility of SSI from the clinical

settings, all the clinical experts, surgical team members, support staffs, and patients need to play

their distinctive roles and responsibilities during the pre-operative period. In addition, the

cautious steps would also be taken during the intra-operative and postoperative periods for

lowering the possibility of infection recurrence (Preventing Surgical Site Infection, 2018) [Refer

to Appendix].

As mentioned in the earlier portion, clinicians can provide a recommendation about the

using of pre-operative showering along with 4% CHG, which is supported evidence by

(Allegranzi, Bischoff & de Jonge, 2016). On the other hand, Mueck & Kao (2017) commented

that it is necessary to minimise the number of bacteria or other harmful microorganisms over the

skin regions, due to which it is evident that CHG soaps are more useful for the prevention of SSI

from wounded or pre-operative places. According to my job role, I need to focus on promoting

some evidence-based approaches for the patients in order to help them in overcoming the threats

of Surgical Site Infection. Through revising the evidence, nurses or other care providers might

provide advice to the patients for reporting skin integrity, skin breaks, or rashes. Patients would

get instruction about leaving the CHG soap on the per-operative areas before rinsing, as it would

help in the effective prevention of SSI.

help in improving the entire public health outcomes by lowering the mortality or morbidity rate

associated with the surgical site infection.

Evidence of Revision

Since the prevalence of SSI is highly expanded in the current healthcare settings,

therefore, evidence for revision can be obtained from different government and institutional

websites. As per the evidence of WHO, for omitting the possibility of SSI from the clinical

settings, all the clinical experts, surgical team members, support staffs, and patients need to play

their distinctive roles and responsibilities during the pre-operative period. In addition, the

cautious steps would also be taken during the intra-operative and postoperative periods for

lowering the possibility of infection recurrence (Preventing Surgical Site Infection, 2018) [Refer

to Appendix].

As mentioned in the earlier portion, clinicians can provide a recommendation about the

using of pre-operative showering along with 4% CHG, which is supported evidence by

(Allegranzi, Bischoff & de Jonge, 2016). On the other hand, Mueck & Kao (2017) commented

that it is necessary to minimise the number of bacteria or other harmful microorganisms over the

skin regions, due to which it is evident that CHG soaps are more useful for the prevention of SSI

from wounded or pre-operative places. According to my job role, I need to focus on promoting

some evidence-based approaches for the patients in order to help them in overcoming the threats

of Surgical Site Infection. Through revising the evidence, nurses or other care providers might

provide advice to the patients for reporting skin integrity, skin breaks, or rashes. Patients would

get instruction about leaving the CHG soap on the per-operative areas before rinsing, as it would

help in the effective prevention of SSI.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Reference List

Allegranzi, B., Bischoff, P., & de Jonge, S. (2016). Surgical Site Infections 1. New WHO

Recommendations on Preoperative Measures for Surgical Site Infection Prevention: an

Evidence-Based Global Perspective. Lancet Infect Dis, 16(12), e276-87. Retrieved

fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bassim_Zayed/publication/

309656390_New_WHO_recommendations_on_preoperative_measures_for_surgical_site

_infection_prevention_an_evidence-based_global_perspective/links/

5b39cddbaca272078501033a/New-WHO-recommendations-on-preoperative-measures-

for-surgical-site-infection-prevention-an-evidence-based-global-perspective.pdf

Badia, J. M., Casey, A. L., Petrosillo, N., Hudson, P. M., Mitchell, S. A., & Crosby, C. (2017).

Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic

review in six European countries. Journal of Hospital Infection, 96(1), 1-15. Retrieved

from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670117301354

Chakravarthy, M., Rangaswamy, S., George, A., Anand, T., Senthilkumar, P., & Rose, S. A.

(2017). Risk stratification of surgical site infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A

prospective case-control study. Journal of Patient Safety and Infection Control, 5(2),

73.

Changes to Prevent Surgical Site Infection. (2018). [online]. Retrieved from

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Changes/ChangestoPreventSurgicalSiteInfection.as

px

Chen, M., Song, X., Chen, L. Z., Lin, Z. D., & Zhang, X. L. (2016). Comparing mechanical

bowel preparation with both oral and systemic antibiotics versus mechanical bowel

preparation and systemic antibiotics alone for the prevention of surgical site infection

after elective colorectal surgery. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 59(1), 70-78.

Retrieved

fromhttps://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/dcr/2016/00000059/00000001/

art00016

Reference List

Allegranzi, B., Bischoff, P., & de Jonge, S. (2016). Surgical Site Infections 1. New WHO

Recommendations on Preoperative Measures for Surgical Site Infection Prevention: an

Evidence-Based Global Perspective. Lancet Infect Dis, 16(12), e276-87. Retrieved

fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bassim_Zayed/publication/

309656390_New_WHO_recommendations_on_preoperative_measures_for_surgical_site

_infection_prevention_an_evidence-based_global_perspective/links/

5b39cddbaca272078501033a/New-WHO-recommendations-on-preoperative-measures-

for-surgical-site-infection-prevention-an-evidence-based-global-perspective.pdf

Badia, J. M., Casey, A. L., Petrosillo, N., Hudson, P. M., Mitchell, S. A., & Crosby, C. (2017).

Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic

review in six European countries. Journal of Hospital Infection, 96(1), 1-15. Retrieved

from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670117301354

Chakravarthy, M., Rangaswamy, S., George, A., Anand, T., Senthilkumar, P., & Rose, S. A.

(2017). Risk stratification of surgical site infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A

prospective case-control study. Journal of Patient Safety and Infection Control, 5(2),

73.

Changes to Prevent Surgical Site Infection. (2018). [online]. Retrieved from

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Changes/ChangestoPreventSurgicalSiteInfection.as

px

Chen, M., Song, X., Chen, L. Z., Lin, Z. D., & Zhang, X. L. (2016). Comparing mechanical

bowel preparation with both oral and systemic antibiotics versus mechanical bowel

preparation and systemic antibiotics alone for the prevention of surgical site infection

after elective colorectal surgery. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 59(1), 70-78.

Retrieved

fromhttps://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/dcr/2016/00000059/00000001/

art00016

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Grundmeier, R. W., Xiao, R., Ross, R. K., Ramos, M. J., Karavite, D. J., Michel, J. J., ... &

Coffin, S. E. (2018). Identifying surgical site infections in electronic health data using

predictive models. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(9),

1160-1166. Retrieved from

https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-abstract/25/9/1160/5047136

Kang, D. G., Holekamp, T. F., Wagner, S. C., & Lehman Jr, R. A. (2015). Intrasite vancomycin

powder for the prevention of surgical site infection in spine surgery: a systematic

literature review. The Spine Journal, 15(4), 762-770. Retrieved

fromhttp://www.academia.edu/download/41701847/Intrasite_Vancomycin_Powder_for_t

he_Prev20160128-27160-1vaphke.pdf

Kunutsor, S. K., Whitehouse, M. R., Blom, A. W., & Beswick, A. D. (2017). Systematic review

of risk prediction scores for surgical site infection or periprosthetic joint infection

following joint arthroplasty. Epidemiology & Infection, 145(9), 1738-1749. Retrieved

from

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c5d8/008b5f03151180128dd9d5f03489d9563c33.pdf

Leaper, D., & Ousey, K. (2015). Evidence update on prevention of surgical site

infection. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 28(2), 158-163. Retrieved

fromhttp://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/23433/1/QCO280202_Leaper_MS_%282%29.pdf

Martin, E. T., Kaye, K. S., Knott, C., Nguyen, H., Santarossa, M., Evans, R., ... & Jaber, L.

(2016). Diabetes and risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. infection control & hospital epidemiology, 37(1), 88-99. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4914132/

Mueck, K. M., & Kao, L. S. (2017). Patients at High-Risk for Surgical Site Infection. Surgical

infections, 18(4), 440-446. Retrieved from

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/sur.2017.058

Preventing Surgical Site Infection. (2018). World health Organization. [online]. Retrieved from

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273154/9789241514385-eng.pdf?ua=1

Grundmeier, R. W., Xiao, R., Ross, R. K., Ramos, M. J., Karavite, D. J., Michel, J. J., ... &

Coffin, S. E. (2018). Identifying surgical site infections in electronic health data using

predictive models. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(9),

1160-1166. Retrieved from

https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-abstract/25/9/1160/5047136

Kang, D. G., Holekamp, T. F., Wagner, S. C., & Lehman Jr, R. A. (2015). Intrasite vancomycin

powder for the prevention of surgical site infection in spine surgery: a systematic

literature review. The Spine Journal, 15(4), 762-770. Retrieved

fromhttp://www.academia.edu/download/41701847/Intrasite_Vancomycin_Powder_for_t

he_Prev20160128-27160-1vaphke.pdf

Kunutsor, S. K., Whitehouse, M. R., Blom, A. W., & Beswick, A. D. (2017). Systematic review

of risk prediction scores for surgical site infection or periprosthetic joint infection

following joint arthroplasty. Epidemiology & Infection, 145(9), 1738-1749. Retrieved

from

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c5d8/008b5f03151180128dd9d5f03489d9563c33.pdf

Leaper, D., & Ousey, K. (2015). Evidence update on prevention of surgical site

infection. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 28(2), 158-163. Retrieved

fromhttp://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/23433/1/QCO280202_Leaper_MS_%282%29.pdf

Martin, E. T., Kaye, K. S., Knott, C., Nguyen, H., Santarossa, M., Evans, R., ... & Jaber, L.

(2016). Diabetes and risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. infection control & hospital epidemiology, 37(1), 88-99. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4914132/

Mueck, K. M., & Kao, L. S. (2017). Patients at High-Risk for Surgical Site Infection. Surgical

infections, 18(4), 440-446. Retrieved from

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/sur.2017.058

Preventing Surgical Site Infection. (2018). World health Organization. [online]. Retrieved from

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273154/9789241514385-eng.pdf?ua=1

9Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Webster, J., & Osborne, S. (2015). Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to

prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (2).Retrieved

from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/84491/1/__staffhome.qut.edu.au_staffgroupb

%24_bozzetto_Documents_2015002448.pdf

Webster, J., & Osborne, S. (2015). Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to

prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (2).Retrieved

from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/84491/1/__staffhome.qut.edu.au_staffgroupb

%24_bozzetto_Documents_2015002448.pdf

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

Appendices

Appendix 1: Annotated Bibliography Table

Appendices

Appendix 1: Annotated Bibliography Table

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

12Identification of Surgical Site Infection in Healthcare Settings

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 20

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.