The Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Workplace Bullying

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|22

|8520

|472

AI Summary

This research paper examines the relationship between interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying, and the role of conflict management styles in preventing conflict escalation. The study was conducted among 761 employees from different organizations in Spain. Results suggest that attempts to actively manage conflict through problem solving may prevent it escalating to higher emotional levels and bullying situations. The paper also explores the mediating effect of relationship conflict on the association between task conflict and workplace bullying.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 1

The Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Workplace Bullying

Jose M. Leon-Perez*

Business Research Unit

ISCTE-Instituto Universitàrio de Lisboa

Lisbon

Portugal

Francisco J. Medina

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

Alicia Arenas

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

&

Lourdes Munduate

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

*Corresponding author: Jose.Leon-Perez@iscte.pt

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their

valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. In addition, the

authors declare that they do not have conflicts of interest.The present study was funded

by a grant from the Junta de Andalucia (Spain) [Ref. CONV2010/256] as well as it was

partially supported by the Strategic Project [Ref. PEst-OE/EGE/UI0315/2011] from the

Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

To be published in: Journal of Managerial Psychology

http://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/products/journals/journals.htm?id=JMP

This article may not exactly replicate the final version published in the journal. It

is not the copy of record.

Publisher copyright and source must be acknowledged

The Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Workplace Bullying

Jose M. Leon-Perez*

Business Research Unit

ISCTE-Instituto Universitàrio de Lisboa

Lisbon

Portugal

Francisco J. Medina

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

Alicia Arenas

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

&

Lourdes Munduate

Department of Social Psychology

University of Seville

Seville

Spain

*Corresponding author: Jose.Leon-Perez@iscte.pt

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their

valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. In addition, the

authors declare that they do not have conflicts of interest.The present study was funded

by a grant from the Junta de Andalucia (Spain) [Ref. CONV2010/256] as well as it was

partially supported by the Strategic Project [Ref. PEst-OE/EGE/UI0315/2011] from the

Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

To be published in: Journal of Managerial Psychology

http://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/products/journals/journals.htm?id=JMP

This article may not exactly replicate the final version published in the journal. It

is not the copy of record.

Publisher copyright and source must be acknowledged

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 2

Article Classification: Research paper

The Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Workplace Bullying

Abstract

Purpose - This paper examines the role that conflict management styles play in the

relationship between interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying.

Design - A survey study was conducted among 761 employees from different

organizations in Spain.

Findings - Results suggest that an escalation of the conflict process from task-related to

relationship conflict may explain bullying situations to some extent. Regarding conflict

management, attempts to actively manage conflict through problem solving may

prevent it escalating to higher emotional levels (relationship conflict) and bullying

situations; in contrast, other conflict management strategies seem to foster conflict

escalation.

Research limitations/implications – The correlational design makes the conclusions on

causality questionable, and future research should examine the dynamic conflict process

in more detail. On the other hand, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study

empirically differentiating interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying.

Value – This study explores how conflict management can prevent conflict escalating

into workplace bullying, which has important implications for occupational health

practitioners and managers.

Keywords: Mobbing. Task conflict. Relationship conflict. Conflict escalation.

Article Classification: Research paper

The Relationship between Interpersonal Conflict and Workplace Bullying

Abstract

Purpose - This paper examines the role that conflict management styles play in the

relationship between interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying.

Design - A survey study was conducted among 761 employees from different

organizations in Spain.

Findings - Results suggest that an escalation of the conflict process from task-related to

relationship conflict may explain bullying situations to some extent. Regarding conflict

management, attempts to actively manage conflict through problem solving may

prevent it escalating to higher emotional levels (relationship conflict) and bullying

situations; in contrast, other conflict management strategies seem to foster conflict

escalation.

Research limitations/implications – The correlational design makes the conclusions on

causality questionable, and future research should examine the dynamic conflict process

in more detail. On the other hand, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study

empirically differentiating interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying.

Value – This study explores how conflict management can prevent conflict escalating

into workplace bullying, which has important implications for occupational health

practitioners and managers.

Keywords: Mobbing. Task conflict. Relationship conflict. Conflict escalation.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 3

Introduction

Workplace bullying is an emergent phenomenon; it refers to “a social interaction

through which one individual (seldom more) is attacked by one or more (seldom more

than four) individuals almost on a daily basis and for periods of many months, bringing

the person into an almost helpless position with potentially high risk of expulsion”

(Leymann, 1996, p. 168). In this regard, research has shown that receiving unwanted

behaviors of a psychological nature has severe negative consequences not only for the

target of bullying but also for the organization as a whole (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2012;

Topa-Cantisano et al., 2007).

Thus, there has been growing interest over the last few years in exploring the

antecedents of workplace bullying (Einarsen et al., 2011). The predominant theoretical

framework used is the so-called ‘work-environment hypothesis’, which conceives

workplace bullying as an extreme social stressor that results both from inadequate

working conditions and other organizational factors (e.g., Giorgi, 2009; Hauge et al.,

2007; Notelaers et al., 2010). Although this has resulted in some valuable suggestions,

recent trends have demonstrated the need to move forward and obtain a more in-depth

knowledge of workplace bullying by focusing on its underlying interpersonal

mechanisms (e.g., Glaso et al., 2009; Neuman and Baron, 2011).

To meet this challenge, we follow Einarsen et al. (2011), who argue that

workplace bullying is “an escalating process in the course of which the person

confronted ends up in an inferior position and becomes the target of systematic negative

social acts” (p. 15). Thus, considering that this escalating process is driven by the

existing interpersonal conflict between parties and their preferences for managing

conflict, the purpose of this study is both to examine the relationship between

interpersonal conflict and bullying at work, and assess the role that conflict management

styles play in such conflict-bullying relationships. Findings will shed some light on the

underlying mechanisms of workplace bullying, and therefore help managers take more

effective steps to prevent bullying at work.

Conflict escalation and workplace bullying

According to Van de Vliert (2010), conflict researchers can shed some light on

the underlying mechanisms of bullying since the two concepts share some definitional

Introduction

Workplace bullying is an emergent phenomenon; it refers to “a social interaction

through which one individual (seldom more) is attacked by one or more (seldom more

than four) individuals almost on a daily basis and for periods of many months, bringing

the person into an almost helpless position with potentially high risk of expulsion”

(Leymann, 1996, p. 168). In this regard, research has shown that receiving unwanted

behaviors of a psychological nature has severe negative consequences not only for the

target of bullying but also for the organization as a whole (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2012;

Topa-Cantisano et al., 2007).

Thus, there has been growing interest over the last few years in exploring the

antecedents of workplace bullying (Einarsen et al., 2011). The predominant theoretical

framework used is the so-called ‘work-environment hypothesis’, which conceives

workplace bullying as an extreme social stressor that results both from inadequate

working conditions and other organizational factors (e.g., Giorgi, 2009; Hauge et al.,

2007; Notelaers et al., 2010). Although this has resulted in some valuable suggestions,

recent trends have demonstrated the need to move forward and obtain a more in-depth

knowledge of workplace bullying by focusing on its underlying interpersonal

mechanisms (e.g., Glaso et al., 2009; Neuman and Baron, 2011).

To meet this challenge, we follow Einarsen et al. (2011), who argue that

workplace bullying is “an escalating process in the course of which the person

confronted ends up in an inferior position and becomes the target of systematic negative

social acts” (p. 15). Thus, considering that this escalating process is driven by the

existing interpersonal conflict between parties and their preferences for managing

conflict, the purpose of this study is both to examine the relationship between

interpersonal conflict and bullying at work, and assess the role that conflict management

styles play in such conflict-bullying relationships. Findings will shed some light on the

underlying mechanisms of workplace bullying, and therefore help managers take more

effective steps to prevent bullying at work.

Conflict escalation and workplace bullying

According to Van de Vliert (2010), conflict researchers can shed some light on

the underlying mechanisms of bullying since the two concepts share some definitional

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 4

elements that allow these interrelated arenas to be linked and additional well-established

theories and practical experiences to be used. On one hand, both concepts focus on the

perception of incompatibility in the interaction between two parties, “with at least one of

them experiencing obstruction or irritation by the other party” (Van de Vliert, 2010: p.

87). On the other hand, whereas time is a key characteristic of bullying, it is not so

important in conflict (i.e., conflict does not have to be repeated but can be a one-off

incident).

In this regard, Leymann (1996) proposed a model of bullying based on case

studies highlighting the fact that bullying behaviors are the result of an escalated

conflict that was not satisfactorily solved. Similarly, Einarsen (1999) differentiated

between “dispute-related bullying” and “predatory bullying”. Whereas the former

originates from highly emotional interpersonal conflicts between workers, the latter is a

non-ethical mechanism used by some workers to maintain their status and/or to get rid

of stress and frustration at work by exerting negative acts on other coworkers. Indeed,

Zapf and Gross (2001) conducted a study based on semi-structured interviews with 20

victims of bullying as well as a survey comparing the coping strategies of victims of

bullying with those of a control group not exposed to negative acts at work. They

concluded that bullying situations are congruent with Glasl’s conflict escalation model

(1994): the situation started with disagreements about the content of the conflict (i.e.,

what conflict researchers describe as a socio-cognitive or task-related conflict, which

refers to disagreements concerning the content of inter-related tasks, including

differences in their views about the distribution of resources or the procedures they

have to follow: De Witt et al., 2012). Then, this conflict turned to more personal issues

in which both parties polarize their positions and differences (i.e., conflict concerning

perceptions of interpersonal incompatibilities and hostility, which is more akin to a

socio-emotional or relationship conflict: De Witt et al., 2012). Finally, as “the

relationship between the parties has become the main source of tension” (Zapf and

Gross, 2001: p. 502), the conflict became destructive since the party with more power

tried to destroy the opposite party’s reputation and self-esteem (i.e., workplace

bullying: Leymann, 1996).

In conclusion, as Ayoko et al. (2003) pointed out, more intense and long lasting

conflicts cause negative behaviors and a variety of emotional responses that constitute

elements that allow these interrelated arenas to be linked and additional well-established

theories and practical experiences to be used. On one hand, both concepts focus on the

perception of incompatibility in the interaction between two parties, “with at least one of

them experiencing obstruction or irritation by the other party” (Van de Vliert, 2010: p.

87). On the other hand, whereas time is a key characteristic of bullying, it is not so

important in conflict (i.e., conflict does not have to be repeated but can be a one-off

incident).

In this regard, Leymann (1996) proposed a model of bullying based on case

studies highlighting the fact that bullying behaviors are the result of an escalated

conflict that was not satisfactorily solved. Similarly, Einarsen (1999) differentiated

between “dispute-related bullying” and “predatory bullying”. Whereas the former

originates from highly emotional interpersonal conflicts between workers, the latter is a

non-ethical mechanism used by some workers to maintain their status and/or to get rid

of stress and frustration at work by exerting negative acts on other coworkers. Indeed,

Zapf and Gross (2001) conducted a study based on semi-structured interviews with 20

victims of bullying as well as a survey comparing the coping strategies of victims of

bullying with those of a control group not exposed to negative acts at work. They

concluded that bullying situations are congruent with Glasl’s conflict escalation model

(1994): the situation started with disagreements about the content of the conflict (i.e.,

what conflict researchers describe as a socio-cognitive or task-related conflict, which

refers to disagreements concerning the content of inter-related tasks, including

differences in their views about the distribution of resources or the procedures they

have to follow: De Witt et al., 2012). Then, this conflict turned to more personal issues

in which both parties polarize their positions and differences (i.e., conflict concerning

perceptions of interpersonal incompatibilities and hostility, which is more akin to a

socio-emotional or relationship conflict: De Witt et al., 2012). Finally, as “the

relationship between the parties has become the main source of tension” (Zapf and

Gross, 2001: p. 502), the conflict became destructive since the party with more power

tried to destroy the opposite party’s reputation and self-esteem (i.e., workplace

bullying: Leymann, 1996).

In conclusion, as Ayoko et al. (2003) pointed out, more intense and long lasting

conflicts cause negative behaviors and a variety of emotional responses that constitute

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 5

workplace bullying. Moreover, personal-oriented conflicts “are likely to lead to long-

lasting relationship conflicts since they contain a high degree of emotionality, which

may manifest itself in negative behaviors such as raised voices, hostility toward others,

and threats and intimidation” (Greer et al., 2008: p. 281). Thus, the intensity of the

conflict seems to be the mechanism or process underlying the association between

interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying. On this basis and considering that

workplace bullying and interpersonal conflict are distinct but interrelated phenomena,

we hypothesize that relationship conflict is a mediator of the relationship between task

conflict and bullying.

Hypothesis 1: Relationship conflict mediates the effect of task conflict on

workplace bullying.

The role of conflict management styles

The way disputes are managed plays a pivotal role in the (de)escalation of

conflict. Broadly speaking, conflict management refers to what the parties (individuals,

groups or organizations) who experience conflict intend to do and what they actually do

(Van de Vliert, 1997). According to the Dual-Concern Model (see De Dreu et al.,

2001), interpersonal conflict at work is managed in accordance with an individual's

concern for the self (competition) and for the other party (cooperation).

Thus, when concern for both the self and the other is high, problem solving is a

more likely strategic choice (e.g., when two employees do inter-related tasks in which

performance depends on their joint outcomes). In contrast, if concern for both self and

the other is low, inaction or avoiding is more likely (e.g., when an issue is trivial and

other issues are more important or when the potential cost of confronting the conflict

outweighs the benefits of addressing it). Moreover, if concern for one’s own outcome is

high but concern for the other is low, this leads to the use of forcing strategies (e.g.,

when a manager imposes a deadline on subordinates according to his/her own priorities

without taking into account the others' preferences or possibilities); on the other hand, if

concern for self is low but concern for the other is high, this results in yielding strategies

(e.g., when employees know that the manager has more power and they have to forego

personal interests).

workplace bullying. Moreover, personal-oriented conflicts “are likely to lead to long-

lasting relationship conflicts since they contain a high degree of emotionality, which

may manifest itself in negative behaviors such as raised voices, hostility toward others,

and threats and intimidation” (Greer et al., 2008: p. 281). Thus, the intensity of the

conflict seems to be the mechanism or process underlying the association between

interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying. On this basis and considering that

workplace bullying and interpersonal conflict are distinct but interrelated phenomena,

we hypothesize that relationship conflict is a mediator of the relationship between task

conflict and bullying.

Hypothesis 1: Relationship conflict mediates the effect of task conflict on

workplace bullying.

The role of conflict management styles

The way disputes are managed plays a pivotal role in the (de)escalation of

conflict. Broadly speaking, conflict management refers to what the parties (individuals,

groups or organizations) who experience conflict intend to do and what they actually do

(Van de Vliert, 1997). According to the Dual-Concern Model (see De Dreu et al.,

2001), interpersonal conflict at work is managed in accordance with an individual's

concern for the self (competition) and for the other party (cooperation).

Thus, when concern for both the self and the other is high, problem solving is a

more likely strategic choice (e.g., when two employees do inter-related tasks in which

performance depends on their joint outcomes). In contrast, if concern for both self and

the other is low, inaction or avoiding is more likely (e.g., when an issue is trivial and

other issues are more important or when the potential cost of confronting the conflict

outweighs the benefits of addressing it). Moreover, if concern for one’s own outcome is

high but concern for the other is low, this leads to the use of forcing strategies (e.g.,

when a manager imposes a deadline on subordinates according to his/her own priorities

without taking into account the others' preferences or possibilities); on the other hand, if

concern for self is low but concern for the other is high, this results in yielding strategies

(e.g., when employees know that the manager has more power and they have to forego

personal interests).

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 6

Moreover, conflict management styles are considered stable traits of individuals

(i.e., types of behavior or generalized behavioral orientations) that affect conflict

escalation and therefore individual and group outcomes (Behfar et al., 2008; Janssen

and Van de Vliert, 1996). For example, managing conflicts in a cooperative and active

way (i.e., problem solving) promotes productive conflict (i.e., integrative or win-win

solutions) and strengthens trust among parties, thereby reducing the level of conflict

present and facilitating team performance (e.g., Chen et al., 2005; Hempel et al., 2009;

Janssen and Van de Vliert, 1996). In contrast, using forcing and yielding styles is

related to conflict escalation because it can lead to a deterioration in the parties’

relationship even though results may satisfy one party in the short run (Behfar et al.,

2008; Janssen and Van de Vliert, 1996). Finally, conflict avoidance entails increased

negative emotion and a higher probability of conflict escalation because it also leaves

conflicts unresolved (e.g., Desivilya and Yagil, 2005; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

Hypothesis 2: Problem solving is negatively related to relationship conflict,

whereas forcing, yielding and avoiding are positively related to relationship

conflict.

As for research on workplace bullying, Baillien et al. (2009) explored 87

bullying incidents and concluded that three processes can explain the development of

bullying: (a) organizational factors that constituted fertile soil for bullying; (b) reactions

to workplace conflicts; and (c) inability to cope with stress and frustration. Thus, as

Ayoko et al. (2003) concluded: “it may not be the conflict events per se that trigger

workplace bullying, but rather the duration and intensity of the conflict, as well as

reactions to conflict events” (p. 297). Indeed, Leymann (1996) claimed that bullying

emerges when conflict is poorly managed or not satisfactorily resolved. Similarly, some

studies have shown that strategies used by the targets of bullying can be related to the

escalation or de-escalation of the bullying situation (e.g., Baillien et al., 2011; Baillien

and De Witte, 2009; Zapf and Gross, 2001): the use of both dominating (forcing) and

passive (such as yielding and avoiding) conflict management styles are positively

related to the escalation of conflict and a higher number of negative behaviors received

by the target; whereas problem solving strategies are associated negatively with

bullying.

Moreover, conflict management styles are considered stable traits of individuals

(i.e., types of behavior or generalized behavioral orientations) that affect conflict

escalation and therefore individual and group outcomes (Behfar et al., 2008; Janssen

and Van de Vliert, 1996). For example, managing conflicts in a cooperative and active

way (i.e., problem solving) promotes productive conflict (i.e., integrative or win-win

solutions) and strengthens trust among parties, thereby reducing the level of conflict

present and facilitating team performance (e.g., Chen et al., 2005; Hempel et al., 2009;

Janssen and Van de Vliert, 1996). In contrast, using forcing and yielding styles is

related to conflict escalation because it can lead to a deterioration in the parties’

relationship even though results may satisfy one party in the short run (Behfar et al.,

2008; Janssen and Van de Vliert, 1996). Finally, conflict avoidance entails increased

negative emotion and a higher probability of conflict escalation because it also leaves

conflicts unresolved (e.g., Desivilya and Yagil, 2005; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

Hypothesis 2: Problem solving is negatively related to relationship conflict,

whereas forcing, yielding and avoiding are positively related to relationship

conflict.

As for research on workplace bullying, Baillien et al. (2009) explored 87

bullying incidents and concluded that three processes can explain the development of

bullying: (a) organizational factors that constituted fertile soil for bullying; (b) reactions

to workplace conflicts; and (c) inability to cope with stress and frustration. Thus, as

Ayoko et al. (2003) concluded: “it may not be the conflict events per se that trigger

workplace bullying, but rather the duration and intensity of the conflict, as well as

reactions to conflict events” (p. 297). Indeed, Leymann (1996) claimed that bullying

emerges when conflict is poorly managed or not satisfactorily resolved. Similarly, some

studies have shown that strategies used by the targets of bullying can be related to the

escalation or de-escalation of the bullying situation (e.g., Baillien et al., 2011; Baillien

and De Witte, 2009; Zapf and Gross, 2001): the use of both dominating (forcing) and

passive (such as yielding and avoiding) conflict management styles are positively

related to the escalation of conflict and a higher number of negative behaviors received

by the target; whereas problem solving strategies are associated negatively with

bullying.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 7

Hypothesis 3: Problem solving is negatively related to workplace bullying,

whereas forcing, yielding and avoiding are positively related to workplace

bullying.

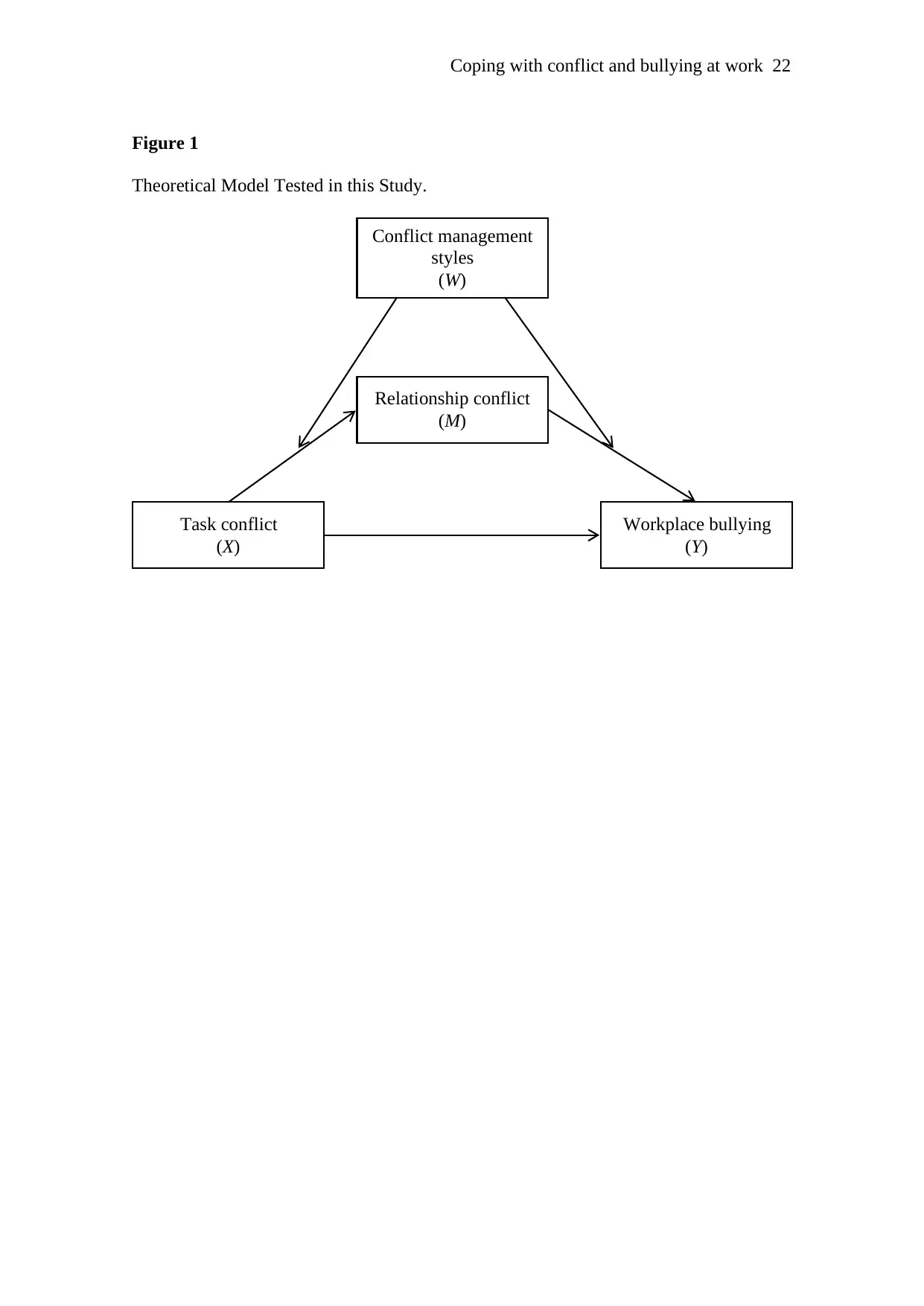

Finally, based on the above mentioned considerations and findings, we

hypothesize that the mediating effect of relationship conflict on the association between

task conflict and workplace bullying depends on the conflict management styles used to

deal with conflict (i.e., moderated-mediation model, in which conflict management

styles moderate the mediation of relationship conflict on task conflict and workplace

bullying, see Figure 1). In particular, conflict management styles will moderate the path

between task conflict and relationship conflict as well as the path between relationship

conflict and workplace bullying.

Hypothesis 4: Conflict management styles moderate the mediating effect of

relationship conflict on task conflict and workplace bullying.

--Please insert Figure 1 here--

Method

Procedure and participants

Data were gathered in three Spanish organizations distributed across sectors in

Andalusia: a large-size organization from the public administration sector, a medium-

size company from the service sector, and a medium-size company from the

manufacturing sector. Participation was voluntary and confidential. Indeed, surveys

were administered to groups of workers in company time with a research assistant

present to answer any questions. Participants placed their completed questionnaires in a

sealed box to ensure the anonymity of responses.

A total of 762 valid questionnaires were returned (response rate of 54.4%). Most

of the participants were men (61.4%) with job tenure of more than five years (86.2% vs.

13.8% who reported job tenure between two and five years, and 4.4% reporting less

than two years). Their ages ranged from 21 to 68 years (M = 41.62; SD = 7.42).

Hypothesis 3: Problem solving is negatively related to workplace bullying,

whereas forcing, yielding and avoiding are positively related to workplace

bullying.

Finally, based on the above mentioned considerations and findings, we

hypothesize that the mediating effect of relationship conflict on the association between

task conflict and workplace bullying depends on the conflict management styles used to

deal with conflict (i.e., moderated-mediation model, in which conflict management

styles moderate the mediation of relationship conflict on task conflict and workplace

bullying, see Figure 1). In particular, conflict management styles will moderate the path

between task conflict and relationship conflict as well as the path between relationship

conflict and workplace bullying.

Hypothesis 4: Conflict management styles moderate the mediating effect of

relationship conflict on task conflict and workplace bullying.

--Please insert Figure 1 here--

Method

Procedure and participants

Data were gathered in three Spanish organizations distributed across sectors in

Andalusia: a large-size organization from the public administration sector, a medium-

size company from the service sector, and a medium-size company from the

manufacturing sector. Participation was voluntary and confidential. Indeed, surveys

were administered to groups of workers in company time with a research assistant

present to answer any questions. Participants placed their completed questionnaires in a

sealed box to ensure the anonymity of responses.

A total of 762 valid questionnaires were returned (response rate of 54.4%). Most

of the participants were men (61.4%) with job tenure of more than five years (86.2% vs.

13.8% who reported job tenure between two and five years, and 4.4% reporting less

than two years). Their ages ranged from 21 to 68 years (M = 41.62; SD = 7.42).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 8

Measures

Exposure to Workplace Bullying was measured using the reduced Spanish

version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revisited (NAQ-R: Einarsen et al., 2009)

developed by Moreno-Jimenez et al. (2007). Participants scored the frequency (response

categories were 1: Never, 2: Now and then, 3: Monthly, 4: Weekly, and 5: Daily) with

which they had been exposed to 14 specific negative acts (bullying behaviors) over the

last six months (e.g., gossiping or having information withheld). Cronbach’s alpha of

the NAQ-R was .88.

Interpersonal Conflict was measured with a 9-item scale that includes both task-

related conflict (e.g., ‘How often are there disagreements about the task you are

working on?’) and relationship conflict (e.g., ‘How often do you experience hostility at

work?’) (see Benitez et al., 2012). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale

ranging from 1 = ‘almost never’ to 5 = ‘very often’. Cronbach’s alpha for task-related

conflict was .76, and for relationship conflict was .92.

Conflict Management Styles were measured with the Dutch Test for Conflict

Handling (DUTCH: see De Dreu et al., 2001). This measure was translated to Spanish

using the standard back-translation procedure. The scale has 16 items, four items for

each conflict management style measured: forcing (e.g. ‘I fight for a favorable outcome

for myself’), avoiding (e.g. ‘I avoid a confrontation about our differences’), problem

solving (e.g. ‘I stand up for both my own and the other’s goals’), and yielding (e.g. ‘I

concur with the other party’). Items were rated on 5-point Likert-type scale ranging

from 1 = ‘almost never’ to 5 = ‘very often’. Cronbach’s alpha for each dimension was:

problem solving .75; forcing .75; avoiding .72; and yielding .76.

Statistical analysis

Prior to forming the various scales for regression analyses, we conducted a

confirmatory factor analysis using asymptotic covariance matrix and maximum

likelihood estimation (since the data were not normally distributed) to assess the

discriminant validity of the substantive constructs measured in this study. Based on

earlier research and theoretical notions, we expected three underlying factors from the

23 items that made up our measures: task conflict, relationship conflict, and workplace

bullying.

Measures

Exposure to Workplace Bullying was measured using the reduced Spanish

version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revisited (NAQ-R: Einarsen et al., 2009)

developed by Moreno-Jimenez et al. (2007). Participants scored the frequency (response

categories were 1: Never, 2: Now and then, 3: Monthly, 4: Weekly, and 5: Daily) with

which they had been exposed to 14 specific negative acts (bullying behaviors) over the

last six months (e.g., gossiping or having information withheld). Cronbach’s alpha of

the NAQ-R was .88.

Interpersonal Conflict was measured with a 9-item scale that includes both task-

related conflict (e.g., ‘How often are there disagreements about the task you are

working on?’) and relationship conflict (e.g., ‘How often do you experience hostility at

work?’) (see Benitez et al., 2012). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale

ranging from 1 = ‘almost never’ to 5 = ‘very often’. Cronbach’s alpha for task-related

conflict was .76, and for relationship conflict was .92.

Conflict Management Styles were measured with the Dutch Test for Conflict

Handling (DUTCH: see De Dreu et al., 2001). This measure was translated to Spanish

using the standard back-translation procedure. The scale has 16 items, four items for

each conflict management style measured: forcing (e.g. ‘I fight for a favorable outcome

for myself’), avoiding (e.g. ‘I avoid a confrontation about our differences’), problem

solving (e.g. ‘I stand up for both my own and the other’s goals’), and yielding (e.g. ‘I

concur with the other party’). Items were rated on 5-point Likert-type scale ranging

from 1 = ‘almost never’ to 5 = ‘very often’. Cronbach’s alpha for each dimension was:

problem solving .75; forcing .75; avoiding .72; and yielding .76.

Statistical analysis

Prior to forming the various scales for regression analyses, we conducted a

confirmatory factor analysis using asymptotic covariance matrix and maximum

likelihood estimation (since the data were not normally distributed) to assess the

discriminant validity of the substantive constructs measured in this study. Based on

earlier research and theoretical notions, we expected three underlying factors from the

23 items that made up our measures: task conflict, relationship conflict, and workplace

bullying.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 9

We then examined a simple mediation or indirect effect model (Hypothesis 1):

the degree to which employees perceive relationship conflict (M) mediates the effect of

task conflict (X) on workplace bullying (Y). We tested this mediation hypothesis using a

SPSS macro provided by Hayes (2013) that facilitates estimation of the indirect effect

(ab) with a bootstrap approach to obtain confidence intervals. The application of

bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) outperforms the normal theory Sobel tests since

it avoids power problems introduced by asymmetric and other nonnormal sampling

distributions of an indirect effect (MacKinnon et al., 2004) and makes Type I error less

likely (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

Finally, we predicted that the conflict management styles used to handle conflict

(W) moderate the first (path task conflict – relationship conflict) and second (path

relationship conflict – workplace bullying) stages of the mediating effect of relationship

conflict on task conflict and workplace bullying (Edwards and Lambert, 2007; Preacher

et al., 2007). This moderated-mediation model (see Figure 1) was tested using the above

mentioned SPSS macro (see model 58: Hayes, 2013), which allows combining

moderation and mediation analyses or conditional indirect effects (Preacher et al.,

2007): the strength of the hypothesized indirect (mediation) effect is conditional on the

value of the moderator (i.e., conflict management styles). The SPSS macro facilitates

the implementation of the recommended bootstrapping methods and permits the probing

of the significance of conditional indirect effects at different values of the moderator

variable.

Given that it is better to view conflict management styles as a set of related

dimensions than as a superordinate construct, we tested each dimension separately to

enable investigation of specific questions on the association of each dimension with a

possible escalation of conflict to workplace bullying (i.e., we conducted four

moderated-mediation models, one for each conflict management style acting as

moderator). However, the effect of the remaining conflict management styles was

controlled as they were introduced as covariates in each moderated-mediation analysis

to reduce the likelihood of Type I error (i.e., familywise error rate when performing

multiple tests).

We then examined a simple mediation or indirect effect model (Hypothesis 1):

the degree to which employees perceive relationship conflict (M) mediates the effect of

task conflict (X) on workplace bullying (Y). We tested this mediation hypothesis using a

SPSS macro provided by Hayes (2013) that facilitates estimation of the indirect effect

(ab) with a bootstrap approach to obtain confidence intervals. The application of

bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) outperforms the normal theory Sobel tests since

it avoids power problems introduced by asymmetric and other nonnormal sampling

distributions of an indirect effect (MacKinnon et al., 2004) and makes Type I error less

likely (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

Finally, we predicted that the conflict management styles used to handle conflict

(W) moderate the first (path task conflict – relationship conflict) and second (path

relationship conflict – workplace bullying) stages of the mediating effect of relationship

conflict on task conflict and workplace bullying (Edwards and Lambert, 2007; Preacher

et al., 2007). This moderated-mediation model (see Figure 1) was tested using the above

mentioned SPSS macro (see model 58: Hayes, 2013), which allows combining

moderation and mediation analyses or conditional indirect effects (Preacher et al.,

2007): the strength of the hypothesized indirect (mediation) effect is conditional on the

value of the moderator (i.e., conflict management styles). The SPSS macro facilitates

the implementation of the recommended bootstrapping methods and permits the probing

of the significance of conditional indirect effects at different values of the moderator

variable.

Given that it is better to view conflict management styles as a set of related

dimensions than as a superordinate construct, we tested each dimension separately to

enable investigation of specific questions on the association of each dimension with a

possible escalation of conflict to workplace bullying (i.e., we conducted four

moderated-mediation models, one for each conflict management style acting as

moderator). However, the effect of the remaining conflict management styles was

controlled as they were introduced as covariates in each moderated-mediation analysis

to reduce the likelihood of Type I error (i.e., familywise error rate when performing

multiple tests).

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 10

Results

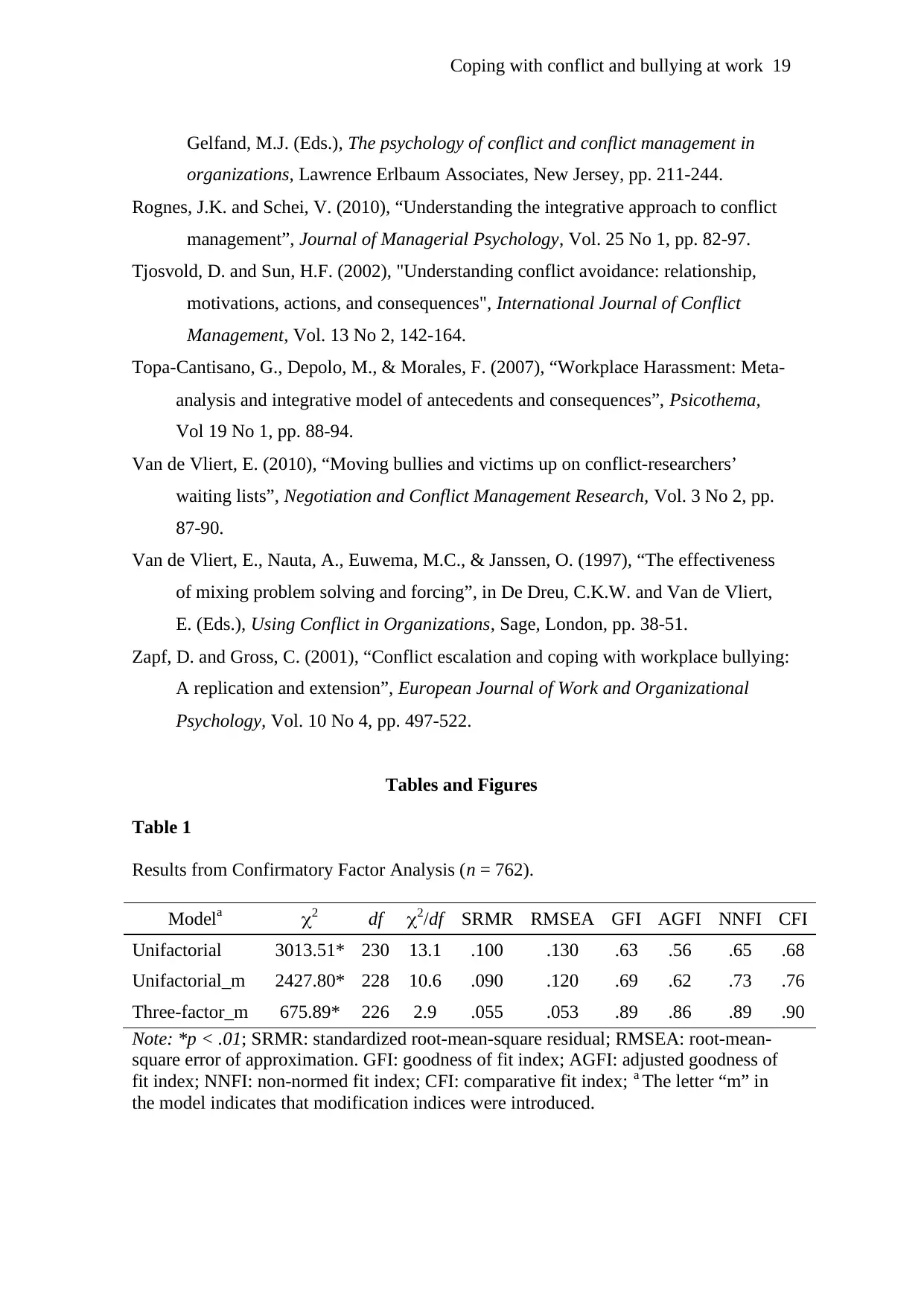

First, we compared the fit of two competing models (unifactorial model vs.

three-factor model) to our data (Kelloway, 1998; Marsh et al., 2004). Models were

based on the polychoric correlation matrix, and asymptotic covariance matrix was

estimated since the data were not normally distributed.

--Please insert Table 1 here—

Results showed that an overall measure (unifactorial model) was associated with

non-acceptable goodness-of-fit statistics even after reducing the number of parameters

in the model as suggested by Modification Indices (see Table 1). According to

Modification Indices, error correlations between NAQ items 8 (“Intimidating behaviors

such as finger pointing, invasion of personal space, shoving, blocking your way”) and

14 (“threats of violence or physical abuse or actual abuse”) were set free to be estimated

since these two items represented the same kind of negative behavior (physically

intimidating bullying: see also Einarsen et al., 2009). Hence, the proposed three-factor

structure demonstrated good fit with the data, suggesting that task conflict, relationship

conflict, and workplace bullying were distinct constructs (see Table 1). Thus, results

allowed us to compute the various constructs by taking the average of their respective

items.

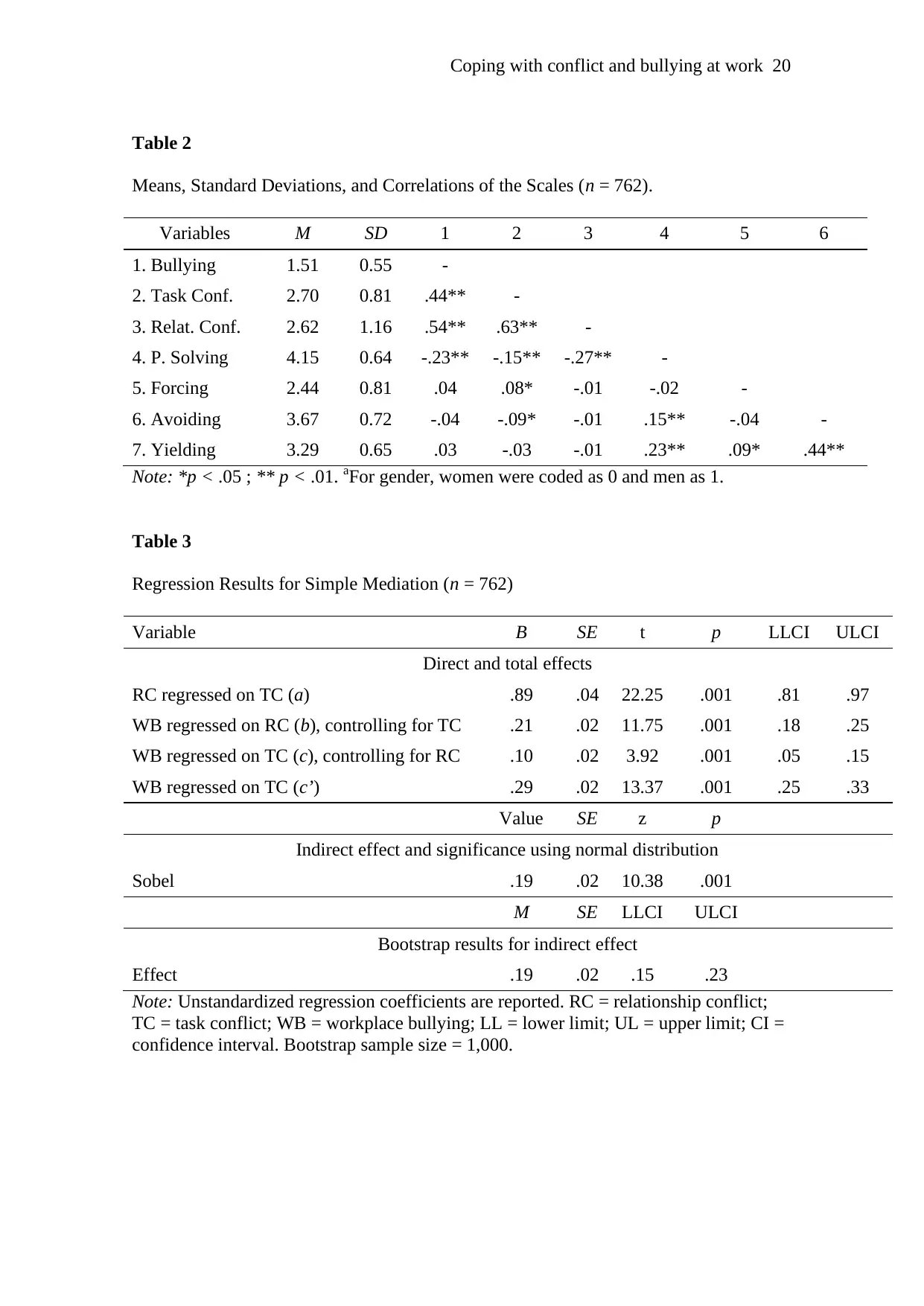

We then tested our hypotheses. Table 2 reports means, standard deviations, and

correlations among the main variables of the study.

--Please insert Table 2 here—

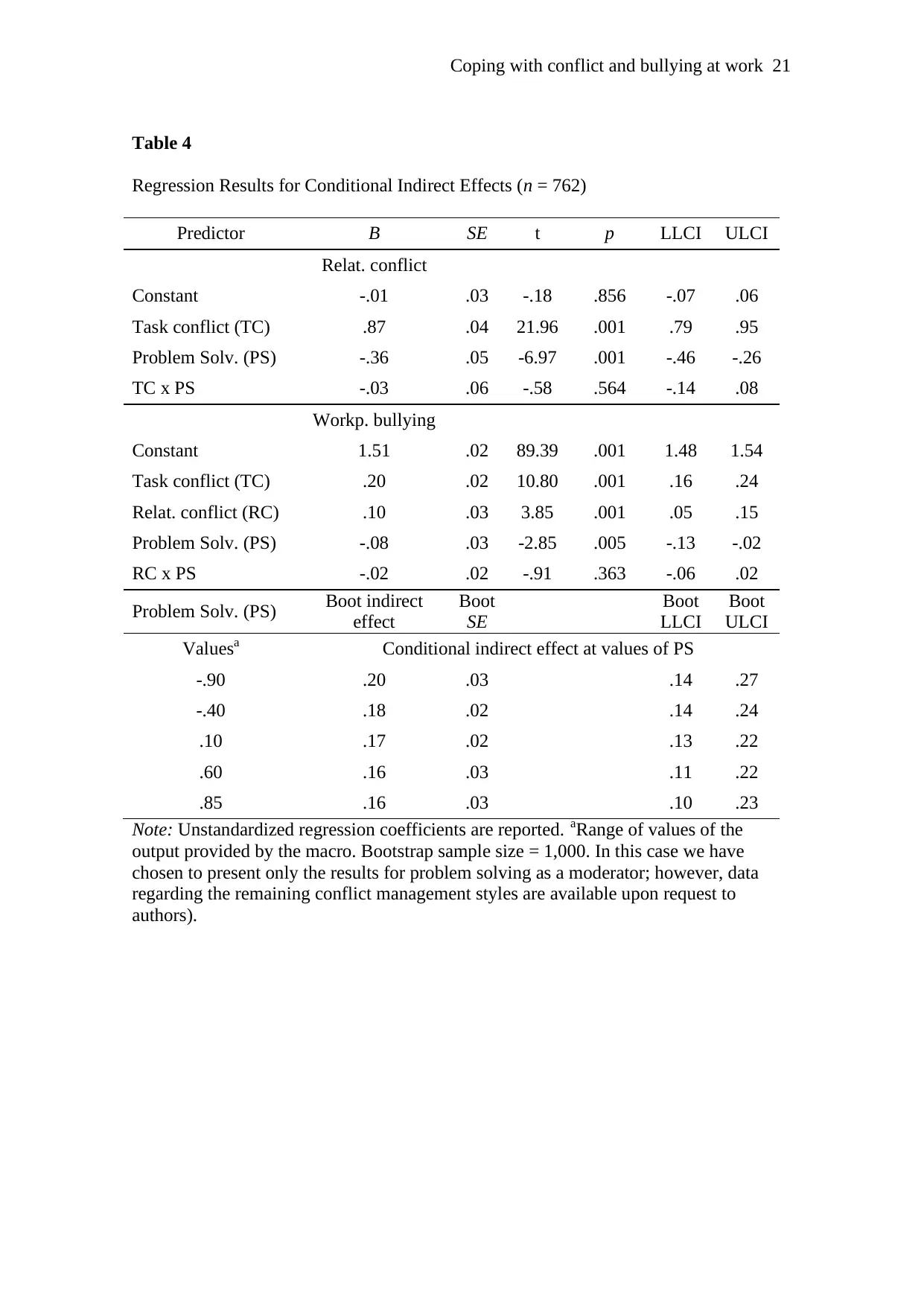

Regarding the simple mediation model (hypothesis 1), results revealed that

relationship conflict partially mediates the association between task conflict and

workplace bullying (see Table 3). Furthermore, the index of mediation was .28

(bootstrapped 95% CIs of .23 to .34) and the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect

of task conflict on workplace bullying was .65 (bootstrapped 95% CIs of .50 to .81),

which means that 65% of the increase in exposure to bullying behaviors was due to the

increase in relationship conflict among employees (see Mackinnon, 2008; Preacher and

Kelley, 2011). Similarly, Preacher and Kelley’s kappa-squared (2011) revealed a

modest indirect effect (k2 = .24; bootstrapped 95% CIs of .20 to .29).

--Please insert Table 3 here—

Results

First, we compared the fit of two competing models (unifactorial model vs.

three-factor model) to our data (Kelloway, 1998; Marsh et al., 2004). Models were

based on the polychoric correlation matrix, and asymptotic covariance matrix was

estimated since the data were not normally distributed.

--Please insert Table 1 here—

Results showed that an overall measure (unifactorial model) was associated with

non-acceptable goodness-of-fit statistics even after reducing the number of parameters

in the model as suggested by Modification Indices (see Table 1). According to

Modification Indices, error correlations between NAQ items 8 (“Intimidating behaviors

such as finger pointing, invasion of personal space, shoving, blocking your way”) and

14 (“threats of violence or physical abuse or actual abuse”) were set free to be estimated

since these two items represented the same kind of negative behavior (physically

intimidating bullying: see also Einarsen et al., 2009). Hence, the proposed three-factor

structure demonstrated good fit with the data, suggesting that task conflict, relationship

conflict, and workplace bullying were distinct constructs (see Table 1). Thus, results

allowed us to compute the various constructs by taking the average of their respective

items.

We then tested our hypotheses. Table 2 reports means, standard deviations, and

correlations among the main variables of the study.

--Please insert Table 2 here—

Regarding the simple mediation model (hypothesis 1), results revealed that

relationship conflict partially mediates the association between task conflict and

workplace bullying (see Table 3). Furthermore, the index of mediation was .28

(bootstrapped 95% CIs of .23 to .34) and the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect

of task conflict on workplace bullying was .65 (bootstrapped 95% CIs of .50 to .81),

which means that 65% of the increase in exposure to bullying behaviors was due to the

increase in relationship conflict among employees (see Mackinnon, 2008; Preacher and

Kelley, 2011). Similarly, Preacher and Kelley’s kappa-squared (2011) revealed a

modest indirect effect (k2 = .24; bootstrapped 95% CIs of .20 to .29).

--Please insert Table 3 here—

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 11

Results from the moderated mediation models partially supported hypotheses 2

and 3 since main effects were found; whereas results did not support hypothesis 4 since

there were no significant interaction effects. Bootstrap CIs corroborated these results as

the indirect and positive effect of task conflict on workplace bullying through

relationship conflict was observed independently of the levels of the conflict

management style used (see Table 4). First, problem solving is negatively related to

relationship conflict (B = -.36, p < .001) and workplace bullying (B = -.08, p < .01).

Second, in the case of forcing as moderator, results revealed a main effect of forcing on

relationship conflict (B = -.08, SE = .04, p = .037, 95% BCa CI of -.16 to -.01). Third, in

the case of avoiding as moderator, results revealed that avoiding is positively related to

relationship conflict (B = .10, SE = .05, p = .042, 95% BCa CI of .01 to .20). Finally,

yielding is positively related to workplace bullying (B = .06, SE = .03, p = .028, 95%

BCa CI of .01 to .12).

--Please insert Table 4 here—

Discussion

This paper addresses workplace bullying as a conflict escalation process and

explores the role played by conflict management styles in the association between

interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying. Results from a confirmatory factor

analysis indicate that interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying are different but

related constructs. This is in line with previous theoretical assumptions that have noted

the differences and commonalities between interpersonal conflict and workplace

bullying and other counterproductive behaviors at work (e.g., Raver and Barling, 2008;

Van de Vliert, 2010).

Our results suggest a conflict escalation process as workplace bullying develops

since relationship conflict mediates the association between task conflict and bullying

at work. This is congruent with previous theoretical assumptions and findings (e.g.,

Einarsen, 1999; Leymann, 1996; Zapf and Gross, 2001), and allows us to connect the

literature on conflict and workplace bullying to obtain a more in-depth knowledge of

the underlying interpersonal mechanisms of bullying at work. Indeed, our results

underline that bullying can be conceived as a conflict escalation process, or a long-

standing conflict, which is developed over a certain period of time.

Results from the moderated mediation models partially supported hypotheses 2

and 3 since main effects were found; whereas results did not support hypothesis 4 since

there were no significant interaction effects. Bootstrap CIs corroborated these results as

the indirect and positive effect of task conflict on workplace bullying through

relationship conflict was observed independently of the levels of the conflict

management style used (see Table 4). First, problem solving is negatively related to

relationship conflict (B = -.36, p < .001) and workplace bullying (B = -.08, p < .01).

Second, in the case of forcing as moderator, results revealed a main effect of forcing on

relationship conflict (B = -.08, SE = .04, p = .037, 95% BCa CI of -.16 to -.01). Third, in

the case of avoiding as moderator, results revealed that avoiding is positively related to

relationship conflict (B = .10, SE = .05, p = .042, 95% BCa CI of .01 to .20). Finally,

yielding is positively related to workplace bullying (B = .06, SE = .03, p = .028, 95%

BCa CI of .01 to .12).

--Please insert Table 4 here—

Discussion

This paper addresses workplace bullying as a conflict escalation process and

explores the role played by conflict management styles in the association between

interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying. Results from a confirmatory factor

analysis indicate that interpersonal conflict and workplace bullying are different but

related constructs. This is in line with previous theoretical assumptions that have noted

the differences and commonalities between interpersonal conflict and workplace

bullying and other counterproductive behaviors at work (e.g., Raver and Barling, 2008;

Van de Vliert, 2010).

Our results suggest a conflict escalation process as workplace bullying develops

since relationship conflict mediates the association between task conflict and bullying

at work. This is congruent with previous theoretical assumptions and findings (e.g.,

Einarsen, 1999; Leymann, 1996; Zapf and Gross, 2001), and allows us to connect the

literature on conflict and workplace bullying to obtain a more in-depth knowledge of

the underlying interpersonal mechanisms of bullying at work. Indeed, our results

underline that bullying can be conceived as a conflict escalation process, or a long-

standing conflict, which is developed over a certain period of time.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 12

According to this conflict escalation perspective, specific conflict management

styles may encourage or discourage conflict and bullying at work. In this regard,

following the Dual-Concern Model (see De Dreu et al., 2001), we explored the role of

several conflict management styles on different conflict escalation stages (i.e., path

task-relationship conflict and path relationship conflict-workplace bullying). Our

results revealed that active attempts to manage conflict through problem solving and

forcing seem the best strategy to prevent task conflict escalating to relationship

conflict; in contrast, trying to avoid conflicts may lead to the escalation of conflict to

more emotional issues (relationship conflict). Overall, these results are in line with

previous studies that have indicated that the most effective way of dealing with task

conflicts is using problem solving in combination with forcing (i.e., reframing the

conflict from our owns perspective and then working through difference by exchanging

accurate information to find compromise consensus: Van de Vliert et al., 1997); in

contrast, although the avoiding approach aims at diminishing conflict and achieving

harmony (i.e., postponing an issue until a better time, or simply withdrawing from a

threatening situation: De Dreu and Van Vianen, 2001), it reflects a lack of conflict

resolution and usually results in negative emotions and conflict escalation (Desivilya

and Yagil, 2005; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

As for workplace bullying, the only strategy associated negatively with

workplace bullying was problem solving or integrating both parties’ interests and

points of view about the conflict. On the other hand, yielding is associated positively

with workplace bullying. Additionally, it should be noted that we did not find

moderation effects of conflict management styles on the mediating effect of

relationship conflict on the task conflict – workplace bullying association. These results

are in line with those of Baillien and De Witte (2009), who reported a negative

association between problem solving and bullying and found no moderation effects of

conflict management styles on the relationship between the occurrence of conflict and

bullying at work. Problem solving is an assertive and cooperative way of dealing with

conflicts and involves an attempt to work with the other person to find a solution which

fully satisfies the concerns of both parties; therefore it helps to reduce the intensity and

hostility of conflict (Rognes and Schei, 2010). This seems the most suitable strategy for

resolving interpersonal conflicts like workplace bullying since other styles may be

According to this conflict escalation perspective, specific conflict management

styles may encourage or discourage conflict and bullying at work. In this regard,

following the Dual-Concern Model (see De Dreu et al., 2001), we explored the role of

several conflict management styles on different conflict escalation stages (i.e., path

task-relationship conflict and path relationship conflict-workplace bullying). Our

results revealed that active attempts to manage conflict through problem solving and

forcing seem the best strategy to prevent task conflict escalating to relationship

conflict; in contrast, trying to avoid conflicts may lead to the escalation of conflict to

more emotional issues (relationship conflict). Overall, these results are in line with

previous studies that have indicated that the most effective way of dealing with task

conflicts is using problem solving in combination with forcing (i.e., reframing the

conflict from our owns perspective and then working through difference by exchanging

accurate information to find compromise consensus: Van de Vliert et al., 1997); in

contrast, although the avoiding approach aims at diminishing conflict and achieving

harmony (i.e., postponing an issue until a better time, or simply withdrawing from a

threatening situation: De Dreu and Van Vianen, 2001), it reflects a lack of conflict

resolution and usually results in negative emotions and conflict escalation (Desivilya

and Yagil, 2005; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

As for workplace bullying, the only strategy associated negatively with

workplace bullying was problem solving or integrating both parties’ interests and

points of view about the conflict. On the other hand, yielding is associated positively

with workplace bullying. Additionally, it should be noted that we did not find

moderation effects of conflict management styles on the mediating effect of

relationship conflict on the task conflict – workplace bullying association. These results

are in line with those of Baillien and De Witte (2009), who reported a negative

association between problem solving and bullying and found no moderation effects of

conflict management styles on the relationship between the occurrence of conflict and

bullying at work. Problem solving is an assertive and cooperative way of dealing with

conflicts and involves an attempt to work with the other person to find a solution which

fully satisfies the concerns of both parties; therefore it helps to reduce the intensity and

hostility of conflict (Rognes and Schei, 2010). This seems the most suitable strategy for

resolving interpersonal conflicts like workplace bullying since other styles may be

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 13

dysfunctional, particularly yielding and accepting the situation (i.e., giving into others’

demands in bullying situations is associated with higher levels of victimization and

severe detrimental consequences for health: Zapf and Gross, 2001).

Limitations and further research

This paper has some methodological limitations that can influence our results

and explain the lack of moderation effects. First, our findings are based on self-report

data from a cross-sectional study; this could lead to common method variance although

we offered variations in the response format and instructed the participants that there

were no correct or incorrect answers (for a discussion, see Brannick et al., 2010).

Indeed, the cross-sectional nature of the data and the use of self-report measures make

it difficult to infer causality. Thus, further research should overcome these limitations

by using a longitudinal design to capture workplace bullying as a conflict escalation

process. Moreover, future studies may benefit from considering workplace bullying as

a gradual process rather than an all-or-nothing phenomenon, thereby exploring the

intensity of conflict in each bullying stage or sub-group (Leon-Perez et al., 2013).

Finally, as our sample was not representative of the Spanish workforce, the

results cannot be generalized. Moreover, considering that Spain has a more collectivist

culture than other European countries (Hofstede et al., 2010), “avoiding conflict can be

undertaken to support relationships and promote the goals of both protagonist” in

conflict (Tjosvold and Sun, 2002: p. 144). Thus, future studies should consider cultural

variables in exploring the role of conflict management (e.g., under what circumstances

is avoiding functional) in the escalation of conflict towards bullying situations.

Managerial implications

Despite the limitations inherent in the study design, our results also have

implications for companies’ conflict management and anti-bullying practices. Our first

recommendation is that companies should focus on developing conflict management

systems to prevent conflict escalation. For example, it seems that the adoption of

problem solving strategies (or integrating both parties’ interests and points of view

about the conflict) helps de-escalate the intensity of a conflict and prevent workplace

bullying. Low-intensity conflicts can be constructive or positive under certain

dysfunctional, particularly yielding and accepting the situation (i.e., giving into others’

demands in bullying situations is associated with higher levels of victimization and

severe detrimental consequences for health: Zapf and Gross, 2001).

Limitations and further research

This paper has some methodological limitations that can influence our results

and explain the lack of moderation effects. First, our findings are based on self-report

data from a cross-sectional study; this could lead to common method variance although

we offered variations in the response format and instructed the participants that there

were no correct or incorrect answers (for a discussion, see Brannick et al., 2010).

Indeed, the cross-sectional nature of the data and the use of self-report measures make

it difficult to infer causality. Thus, further research should overcome these limitations

by using a longitudinal design to capture workplace bullying as a conflict escalation

process. Moreover, future studies may benefit from considering workplace bullying as

a gradual process rather than an all-or-nothing phenomenon, thereby exploring the

intensity of conflict in each bullying stage or sub-group (Leon-Perez et al., 2013).

Finally, as our sample was not representative of the Spanish workforce, the

results cannot be generalized. Moreover, considering that Spain has a more collectivist

culture than other European countries (Hofstede et al., 2010), “avoiding conflict can be

undertaken to support relationships and promote the goals of both protagonist” in

conflict (Tjosvold and Sun, 2002: p. 144). Thus, future studies should consider cultural

variables in exploring the role of conflict management (e.g., under what circumstances

is avoiding functional) in the escalation of conflict towards bullying situations.

Managerial implications

Despite the limitations inherent in the study design, our results also have

implications for companies’ conflict management and anti-bullying practices. Our first

recommendation is that companies should focus on developing conflict management

systems to prevent conflict escalation. For example, it seems that the adoption of

problem solving strategies (or integrating both parties’ interests and points of view

about the conflict) helps de-escalate the intensity of a conflict and prevent workplace

bullying. Low-intensity conflicts can be constructive or positive under certain

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 14

circumstances, e.g. in jobs where some controversy among employees on aspects related

to their tasks may encourage a climate of creativity and innovation (e.g., De Witt et al.,

2012; Medina et al., 2005). However, when conflict reaches a higher intensity, it

produces negative emotional reactions such as increased stress, decreased job

satisfaction, and fear of social rejection (e.g., De Witt et al., 2012; Friedman et al.,

2000). Thus, companies can reduce conflict escalation to improve employees’ health

and well-being and also productivity, corporate image and organizational brand by

providing training on effective conflict management (e.g., De Dreu and Van Vianen,

2001; De Witt et al., 2012; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

In addition, we recommend pairing strengthening individual strategies with

structural interventions (i.e., organizational strategies) since the development of anti-

bullying policies or alternative dispute resolution systems may contribute to creating a

constructive conflict resolution culture in the organization (e.g., Giorgi, 2010; Heames

& Harvey, 2006; Leon-Perez et al., 2012).

Conclusion

This paper gives opportunities for bridging conflict and workplace bullying

research arenas. Our results suggest that workplace bullying can be conceived of as a

conflict escalation process that is perceived as stressful and threatening, leading

employees to experience negative emotions. Thus, a preventive approach seems to be

more appropriate to counteract bullying at work in this conflict management

framework.

References

Ayoko, O.B., Callan, V.J., & Härtel, C.E.J. (2003), “Workplace conflict, bullying, and

counterproductive behaviors”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis,

Vol. 11 No 4, pp. 283-301.

Baillien, E. and De Witte, H. (2009), “The relationship between the occurrence of

conflicts in the work unit, the conflict management styles in the work unit and

workplace bullying”, Psychologica Belgica, Vol. 49 No 4, pp. 207-226.

circumstances, e.g. in jobs where some controversy among employees on aspects related

to their tasks may encourage a climate of creativity and innovation (e.g., De Witt et al.,

2012; Medina et al., 2005). However, when conflict reaches a higher intensity, it

produces negative emotional reactions such as increased stress, decreased job

satisfaction, and fear of social rejection (e.g., De Witt et al., 2012; Friedman et al.,

2000). Thus, companies can reduce conflict escalation to improve employees’ health

and well-being and also productivity, corporate image and organizational brand by

providing training on effective conflict management (e.g., De Dreu and Van Vianen,

2001; De Witt et al., 2012; Dijkstra et al., 2009).

In addition, we recommend pairing strengthening individual strategies with

structural interventions (i.e., organizational strategies) since the development of anti-

bullying policies or alternative dispute resolution systems may contribute to creating a

constructive conflict resolution culture in the organization (e.g., Giorgi, 2010; Heames

& Harvey, 2006; Leon-Perez et al., 2012).

Conclusion

This paper gives opportunities for bridging conflict and workplace bullying

research arenas. Our results suggest that workplace bullying can be conceived of as a

conflict escalation process that is perceived as stressful and threatening, leading

employees to experience negative emotions. Thus, a preventive approach seems to be

more appropriate to counteract bullying at work in this conflict management

framework.

References

Ayoko, O.B., Callan, V.J., & Härtel, C.E.J. (2003), “Workplace conflict, bullying, and

counterproductive behaviors”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis,

Vol. 11 No 4, pp. 283-301.

Baillien, E. and De Witte, H. (2009), “The relationship between the occurrence of

conflicts in the work unit, the conflict management styles in the work unit and

workplace bullying”, Psychologica Belgica, Vol. 49 No 4, pp. 207-226.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 15

Baillien, E., Neyens, I., De Witte, H., & De Cuyper, N. (2009), “A qualitative study on

the development of workplace bullying: Towards a three way model”, Journal of

Community & Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 19 No 1, pp. 1-16.

Baillien, E., Notelaers, G., De Witte, H., & Matthiesen, S.B. (2011), “The relationship

between the work unit’s conflict management styles and bullying at work:

Moderation by conflict frequency”, Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 32

No 3, pp. 401-419.

Behfar, K.J., Peterson, R.S., Mannix, E.A., & Trochim, W.M.K. (2008), “The critical

role of conflict resolution in teams: a close look at the links between conflict type,

conflict management strategies, and team outcomes”, Journal of Applied

Psychology, Vol. 93 No 1, 170–188.

Benitez, M., Leon-Perez, J.M., Ramirez-Marin, J.Y., Medina, F.J., & Munduate, L.

(2012), “Validation of the interpersonal conflict at work questionnaire among

Spanish employees”, Estudios de Psicología, Vol. 33 No 3, 263-275.

Brannick, M.T., Chan, D., Conway, J.M., Lance, C.E., & Spector, P.E. (2010), “What is

method variance and how can we cope with it? A panel discussion”,

Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 13 No 3, 407-420.

Chen, G., Liu, C., & Tjosvold, D. (2005), “Conflict management for effective top

management teams and innovation”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol 42 No

2, 277-300.

De Dreu, C.K.W., Evers, A., Beersma, B., Kluwer, E.S., & Nauta, A. (2001), “A

theory-based measure of conflict management strategies in the work place”,

Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22 No 6, pp. 645-668.

De Dreu, C.K.W. and Van Vianen, A.E.M. (2001), “Managing relationship conflict and

the effectiveness of organizational teams”, Journal of Organizational Behavior,

Vol. 22 No 3, pp. 309-328.

De Wit, F.R., Greer, L.L., & Jehn, K.A. (2012), “The paradox of intragroup conflict: A

meta-analysis”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 97 No 2, pp. 360-390.

Desivilya, H., and Yagil, D. (2005). The role of emotions in conflict management: The

case of work teams. International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol 16 No

1, 55– 69.

Baillien, E., Neyens, I., De Witte, H., & De Cuyper, N. (2009), “A qualitative study on

the development of workplace bullying: Towards a three way model”, Journal of

Community & Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 19 No 1, pp. 1-16.

Baillien, E., Notelaers, G., De Witte, H., & Matthiesen, S.B. (2011), “The relationship

between the work unit’s conflict management styles and bullying at work:

Moderation by conflict frequency”, Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 32

No 3, pp. 401-419.

Behfar, K.J., Peterson, R.S., Mannix, E.A., & Trochim, W.M.K. (2008), “The critical

role of conflict resolution in teams: a close look at the links between conflict type,

conflict management strategies, and team outcomes”, Journal of Applied

Psychology, Vol. 93 No 1, 170–188.

Benitez, M., Leon-Perez, J.M., Ramirez-Marin, J.Y., Medina, F.J., & Munduate, L.

(2012), “Validation of the interpersonal conflict at work questionnaire among

Spanish employees”, Estudios de Psicología, Vol. 33 No 3, 263-275.

Brannick, M.T., Chan, D., Conway, J.M., Lance, C.E., & Spector, P.E. (2010), “What is

method variance and how can we cope with it? A panel discussion”,

Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 13 No 3, 407-420.

Chen, G., Liu, C., & Tjosvold, D. (2005), “Conflict management for effective top

management teams and innovation”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol 42 No

2, 277-300.

De Dreu, C.K.W., Evers, A., Beersma, B., Kluwer, E.S., & Nauta, A. (2001), “A

theory-based measure of conflict management strategies in the work place”,

Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22 No 6, pp. 645-668.

De Dreu, C.K.W. and Van Vianen, A.E.M. (2001), “Managing relationship conflict and

the effectiveness of organizational teams”, Journal of Organizational Behavior,

Vol. 22 No 3, pp. 309-328.

De Wit, F.R., Greer, L.L., & Jehn, K.A. (2012), “The paradox of intragroup conflict: A

meta-analysis”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 97 No 2, pp. 360-390.

Desivilya, H., and Yagil, D. (2005). The role of emotions in conflict management: The

case of work teams. International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol 16 No

1, 55– 69.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 16

Dijkstra, M.T.M., De Dreu, C.K.W., Evers, A., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2009),

“Passive responses to interpersonal conflict at work amplify employee strain”,

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 18 No 4 , 405-

423.

Edwards, J.R. and Lambert, L.S. (2007), “Methods for integrating moderation and

mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis”,

Psychological Methods, Vol. 12 No 1, pp. 1-22.

Einarsen, S. (1999), “The nature and causes of bullying at work”, Journal of Manpower,

Vol 20 No 1, pp. 16-27.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009), “Measuring exposure to bullying and

harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the

Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised”, Work & Stress, Vol. 23 No 1, pp. 24-44.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C.L. (2011), Bullying and Harassment in

the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice (2nd Ed.), CRC

Press, London.

Friedman, R.A., Tidd, S.T., Currall, S.C., & Tsai, J.C. (2000), “What goes around

comes around: The impact of personal conflict style on work conflict and stress”,

International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol. 11 No 1, pp. 32-55.

Giorgi, G. (2009), “Workplace bullying risk assessment in 12 Italian organizations”,

International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 2 No 1, pp. 34-47.

Giorgi, G. (2010), “Workplace bullying partially mediates the climate-health

relationship”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 25 No 7, pp. 727-740.

Glasl, F. (1994), Konfliktmanagement. Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte und Berater

[Conflict Management: A Handbook for Managers and Consultants], Haupt,

Bern.

Glaso, L., Nielsen, M.B., & Einarsen, S. (2009), “Interpersonal problems among

perpetrators and targets of workplace bullying”, Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, Vol. 39 No 6, pp. 1316-1333.

Greer, L.L., Jehn, K.A., & Mannix, E.A. (2008), “Conflict transformation: A

longitudinal investigation of the relationships between different types of

intragroup conflict and the moderating role of conflict resolution”, Small Group

Research, Vol. 39 No 3, pp. 278-302.

Dijkstra, M.T.M., De Dreu, C.K.W., Evers, A., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2009),

“Passive responses to interpersonal conflict at work amplify employee strain”,

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 18 No 4 , 405-

423.

Edwards, J.R. and Lambert, L.S. (2007), “Methods for integrating moderation and

mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis”,

Psychological Methods, Vol. 12 No 1, pp. 1-22.

Einarsen, S. (1999), “The nature and causes of bullying at work”, Journal of Manpower,

Vol 20 No 1, pp. 16-27.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009), “Measuring exposure to bullying and

harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the

Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised”, Work & Stress, Vol. 23 No 1, pp. 24-44.

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C.L. (2011), Bullying and Harassment in

the Workplace. Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice (2nd Ed.), CRC

Press, London.

Friedman, R.A., Tidd, S.T., Currall, S.C., & Tsai, J.C. (2000), “What goes around

comes around: The impact of personal conflict style on work conflict and stress”,

International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol. 11 No 1, pp. 32-55.

Giorgi, G. (2009), “Workplace bullying risk assessment in 12 Italian organizations”,

International Journal of Workplace Health Management, Vol. 2 No 1, pp. 34-47.

Giorgi, G. (2010), “Workplace bullying partially mediates the climate-health

relationship”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 25 No 7, pp. 727-740.

Glasl, F. (1994), Konfliktmanagement. Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte und Berater

[Conflict Management: A Handbook for Managers and Consultants], Haupt,

Bern.

Glaso, L., Nielsen, M.B., & Einarsen, S. (2009), “Interpersonal problems among

perpetrators and targets of workplace bullying”, Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, Vol. 39 No 6, pp. 1316-1333.

Greer, L.L., Jehn, K.A., & Mannix, E.A. (2008), “Conflict transformation: A

longitudinal investigation of the relationships between different types of

intragroup conflict and the moderating role of conflict resolution”, Small Group

Research, Vol. 39 No 3, pp. 278-302.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Coping with conflict and bullying at work 17

Hauge, L.J., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2007), “Relationships between stressful work

environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study”, Work &

Stress, Vol. 21 No 3, pp. 220-242.

Hayes, A.F. (2013), An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional

Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, Guilford Press, New York, NY.

Heames, J., and Harvey, M. (2006), “Workplace bullying: a cross-level assessment”,

Management Decision, Vol. 44 No 9, pp. 1214-1230.

Hempel, P.S., Zhang, Z-X., & Tjosvold, D. (2009), “Conflict management between and

within teams for trusting relationships and performance in China”, Journal of

Organizational Behavior, Vol. 30 No 1, 41-65.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010), Cultures and organizations.

Software of the mind (3rd Ed.), McGraw-Hill, New York.

Janssen, O., and Van de Vliert, E. (1996), “Concern for the other’s goals: Key to (de-)

escalation of conflict”, International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol.7 No

2, 99-120.

Kelloway, E.K. (1998), Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A

Researcher’s Guide, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Leon-Perez, J.M., Arenas, A., & Butts, T. (2012), “Effectiveness of a conflict

management intervention to prevent workplace bullying”, in Tehrani, N. (Ed.),

Workplace Bullying: Symptoms and Solutions, Routledge Press, London, pp. 230-

243.

Leon-Perez, J.M., Notelaers, G., Arenas, A., Medina, F.J., & Munduate, L. (2013),

“Identifying victims of workplace bullying by integrating traditional estimation

methods into a latent class cluster approach”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence,

in press.

Leymann, H. (1996), “The content and development of mobbing at work”, European

Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 5 No 2, pp. 165-184.

MacKinnon, D.P. (2008), Introduction to statistical mediation analysis, Erlbaum,

Mahwah, NJ.

MacKinnon, D.P., Lockwood, C.M., & Williams, J. (2004), “Confidence limits for the