Analysis of Three Interprofessional Collaboration Models in Healthcare

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|11

|8413

|106

Report

AI Summary

This document analyzes three interprofessional collaboration models in healthcare education, focusing on programs at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, the University of Florida, and the University of Washington. The models include a didactic program emphasizing team-building and patient-centered care, a community-based experience highlighting service and resource impact, and an interprofessional-simulation experience developing communication and leadership skills. The report highlights common themes such as understanding professional identity, commitment from departments, diverse calendar agreements, curricular mapping, mentor and faculty training, a sense of community, adequate physical space, technology, and community relationships as critical resources for success. The paper underscores the importance of administrative support, infrastructure, faculty commitment, and student participation for developing IPE-centered programs, ultimately aiming to improve healthcare outcomes through collaborative practice. The document also provides a detailed overview of interprofessional collaboration and education, including definitions, characteristics, and the benefits of team-based approaches.

Interprofessionalcollaboration: three

best practice models of

interprofessionaleducation

Diane R. Bridges, MSN, RN, CCM 1*, Richard A. Davidson,

MD, MPH 2, Peggy Soule Odegard,PharmD, BCPS, CDE,

FASCP 3, Ian V. Maki, MPH 3 and John Tomkowiak, MD, MOL4

1Department of InterprofessionalHealthcare Studies, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science, North Chicago, IL, USA;2Office of InterprofessionalEducation, University of Florida,

Gainesville, FL, USA;3Office of the Dean-Regional Affairs, UW School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA;

4Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL, USA

Interprofessionaleducationis a collaborativeapproachto develophealthcarestudentsas future

interprofessionalteam members and a recommendation suggested by the Institute of Medicine.Complex

medical issues can be best addressed by interprofessional teams. Training future healthcare providers to work

in such teams willhelp facilitate this modelresulting in improved healthcare outcomes for patients.In

this paper,three universities,the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science,the University of

Florida and the University ofWashington describe their training curricula models ofcollaborative and

interprofessional education.

The models represent a didactic program, a community-based experience and an interprofessional-simulation

experience. The didactic program emphasizes interprofessional team building skills, knowledge of professions,

patient centered care, service learning, the impact of culture on healthcare delivery and an interprofessional

clinicalcomponent.The community-based experience demonstrates how interprofessionalcollaborations

provide service to patients and how the environment and availability of resources impact one’s health status.

The interprofessional-simulation experience describes clinicalteam skills training in both formative and

summative simulations used to develop skills in communication and leadership.

One common theme leading to a successful experience among these three interprofessional models included

helping students to understand their own professionalidentity while gaining an understanding ofother

professional’s roles on the health care team.Commitment from departments and colleges, diverse calendar

agreements, curricular mapping, mentor and faculty training, a sense of community, adequate physical space,

technology,and community relationships were allidentified as criticalresources for a successfulprogram.

Summary recommendations for best practices included the need for administrative support, interprofessional

programmaticinfrastructure,committed faculty,and the recognition ofstudentparticipation askey

components to success for anyone developing an IPE centered program.

Keywords:interprofessional; healthcare teams; collaboration; interprofessional education; interprofessional curricula models

Received: 25 January 2011;Revised: 25 March 2011;Accepted: 3 March 2011; Published: 8 April2011

Today’spatientshave complex health needsand

typicallyrequire more than one disciplineto

addressissuesregarding theirhealth status(1).

In 2001 a recommendation by the Institute of Medicine

Committeeon Quality of Health Care in America

suggestedthat healthcareprofessionalsworking in

interprofessionalteams can bestcommunicate and ad-

dress these complex and challenging needs (1,2). This

interprofessionalapproach may allow sharing of exper-

tise and perspectives to form a common goal of restoring

or maintaining an individual’shealth and improving

outcomes while combining resources (1, 3).

Interprofessionaleducation (IPE)is an approach to

develop healthcare students for future interprofessional

teams. Students trained using an IPE approach are more

likely to become collaborativeinterprofessionalteam

(page number not for citation purpose)

æ TREND ARTICLE

Medical Education Online 2011. # 2011 Diane R. Bridges et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

Noncommercial3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting allnon-commercialuse, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the originalwork is properly cited.

1

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 - DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

best practice models of

interprofessionaleducation

Diane R. Bridges, MSN, RN, CCM 1*, Richard A. Davidson,

MD, MPH 2, Peggy Soule Odegard,PharmD, BCPS, CDE,

FASCP 3, Ian V. Maki, MPH 3 and John Tomkowiak, MD, MOL4

1Department of InterprofessionalHealthcare Studies, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science, North Chicago, IL, USA;2Office of InterprofessionalEducation, University of Florida,

Gainesville, FL, USA;3Office of the Dean-Regional Affairs, UW School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA;

4Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL, USA

Interprofessionaleducationis a collaborativeapproachto develophealthcarestudentsas future

interprofessionalteam members and a recommendation suggested by the Institute of Medicine.Complex

medical issues can be best addressed by interprofessional teams. Training future healthcare providers to work

in such teams willhelp facilitate this modelresulting in improved healthcare outcomes for patients.In

this paper,three universities,the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science,the University of

Florida and the University ofWashington describe their training curricula models ofcollaborative and

interprofessional education.

The models represent a didactic program, a community-based experience and an interprofessional-simulation

experience. The didactic program emphasizes interprofessional team building skills, knowledge of professions,

patient centered care, service learning, the impact of culture on healthcare delivery and an interprofessional

clinicalcomponent.The community-based experience demonstrates how interprofessionalcollaborations

provide service to patients and how the environment and availability of resources impact one’s health status.

The interprofessional-simulation experience describes clinicalteam skills training in both formative and

summative simulations used to develop skills in communication and leadership.

One common theme leading to a successful experience among these three interprofessional models included

helping students to understand their own professionalidentity while gaining an understanding ofother

professional’s roles on the health care team.Commitment from departments and colleges, diverse calendar

agreements, curricular mapping, mentor and faculty training, a sense of community, adequate physical space,

technology,and community relationships were allidentified as criticalresources for a successfulprogram.

Summary recommendations for best practices included the need for administrative support, interprofessional

programmaticinfrastructure,committed faculty,and the recognition ofstudentparticipation askey

components to success for anyone developing an IPE centered program.

Keywords:interprofessional; healthcare teams; collaboration; interprofessional education; interprofessional curricula models

Received: 25 January 2011;Revised: 25 March 2011;Accepted: 3 March 2011; Published: 8 April2011

Today’spatientshave complex health needsand

typicallyrequire more than one disciplineto

addressissuesregarding theirhealth status(1).

In 2001 a recommendation by the Institute of Medicine

Committeeon Quality of Health Care in America

suggestedthat healthcareprofessionalsworking in

interprofessionalteams can bestcommunicate and ad-

dress these complex and challenging needs (1,2). This

interprofessionalapproach may allow sharing of exper-

tise and perspectives to form a common goal of restoring

or maintaining an individual’shealth and improving

outcomes while combining resources (1, 3).

Interprofessionaleducation (IPE)is an approach to

develop healthcare students for future interprofessional

teams. Students trained using an IPE approach are more

likely to become collaborativeinterprofessionalteam

(page number not for citation purpose)

æ TREND ARTICLE

Medical Education Online 2011. # 2011 Diane R. Bridges et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

Noncommercial3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting allnon-commercialuse, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the originalwork is properly cited.

1

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 - DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

members who show respect and positive attitudes towards

each other and work towards improving patient outcomes

(35).

What is interprofessionalcollaboration and

practice?

According to the Canadian InterprofessionalHealth

Collaborative,interprofessionalcollaboration is a ‘part-

nership between a team of health providers and a client in

a participatory collaborative and coordinated approach

to shared decision making around health and social

issues’(6). Interprofessionalcollaborative practice has

been defined as a process which includes communication

and decision-making,enabling a synergistic influence of

grouped knowledge and skills (7). Elements of collabora-

tive practice include responsibility,accountability,coor-

dination, communication,cooperation,assertiveness,

autonomy,and mutualtrust and respect(7). It is this

partnership thatcreatesan interprofessionalteam de-

signed to work on common goalsto improve patient

outcomes.Collaborative interactions exhibita blending

of professional cultures and are achieved though sharing

skills and knowledge to improve the quality ofpatient

care (8, 9).

There are importantcharacteristicsthat determine

team effectiveness,including members seeing their roles

as importantto the team,open communication,the

existence of autonomy, and equality of resources (9). It is

important to note that poor interprofessionalcollabora-

tion can have a negative impact on the quality of patient

care (10).Thus skills in working as an interprofessional

team,gained through interprofessionaleducation,are

important for high-quality care.

What is interprofessionaleducation?

IPE has been defined as ‘members or students of two or

more professions associated with health or socialcare,

engaged in learning with,from and abouteach other’

(4, 11). IPE provides an ability to share skills and

knowledge between professions and allows for a better

understanding, shared values, and respect for the roles of

other healthcare professionals (5,11, 12). Casto etal.

describedthe importanceof developingearly IPE

curricula and offering them beforestudentsbegin to

practice in order to build a basic value of working within

interprofessional teams (13, 14). The desired end result is

to develop an interprofessional,team-based,collabora-

tive approach thatimproves patientoutcomes and the

quality of care (5, 15).

In this paper we showcase three exemplary models of

collaborativeand interprofessionaleducationalexperi-

ences so thatother institutions may benefitfrom these

when creating interprofessional curricula.

Models of interprofessionalcollaborative

student experiences

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science: HMTD 500 InterprofessionalHealthcare

Teams course

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science (RFUMS) has responded to the challenge of

interprofessional training by designing a one-credit-hour,

pass/failcoursecalled HMTD 500: Interprofessional

HealthcareTeams(2, 16). The courseis a required

experiential learning opportunity where students interact

in interprofessionalhealthcare teams.Students focus on

a collaborative approach to patient-centered care,with

emphasison team interaction,communication,service

learning,evidence-based practice,and quality improve-

ment.

The course,which was instituted in 2004,spans the

months ofAugustMarch every year,and has evolved

into three separate components each with its own course

director:a required didacticcomponent(Table 1), a

required servicelearningcomponent,and a clinical

component with limited enrollment.

During the course,all first-yearstudents(approxi-

mately 480) are grouped into 16-member interprofessional

teams.Each team has student representation from allo-

pathic and podiatric medicine, clinical laboratory, medical

radiation physic,nurse anesthetists,pathologists’assis-

tants, psychology, and physician assistants. Each team has

a faculty or staff member, with a minimum of a master’s

degree, serving as a mentor. Mentors are trained prior to

each class,and the lunch hour of every class day is set

aside for mentors to review material and ask questions if

necessary.

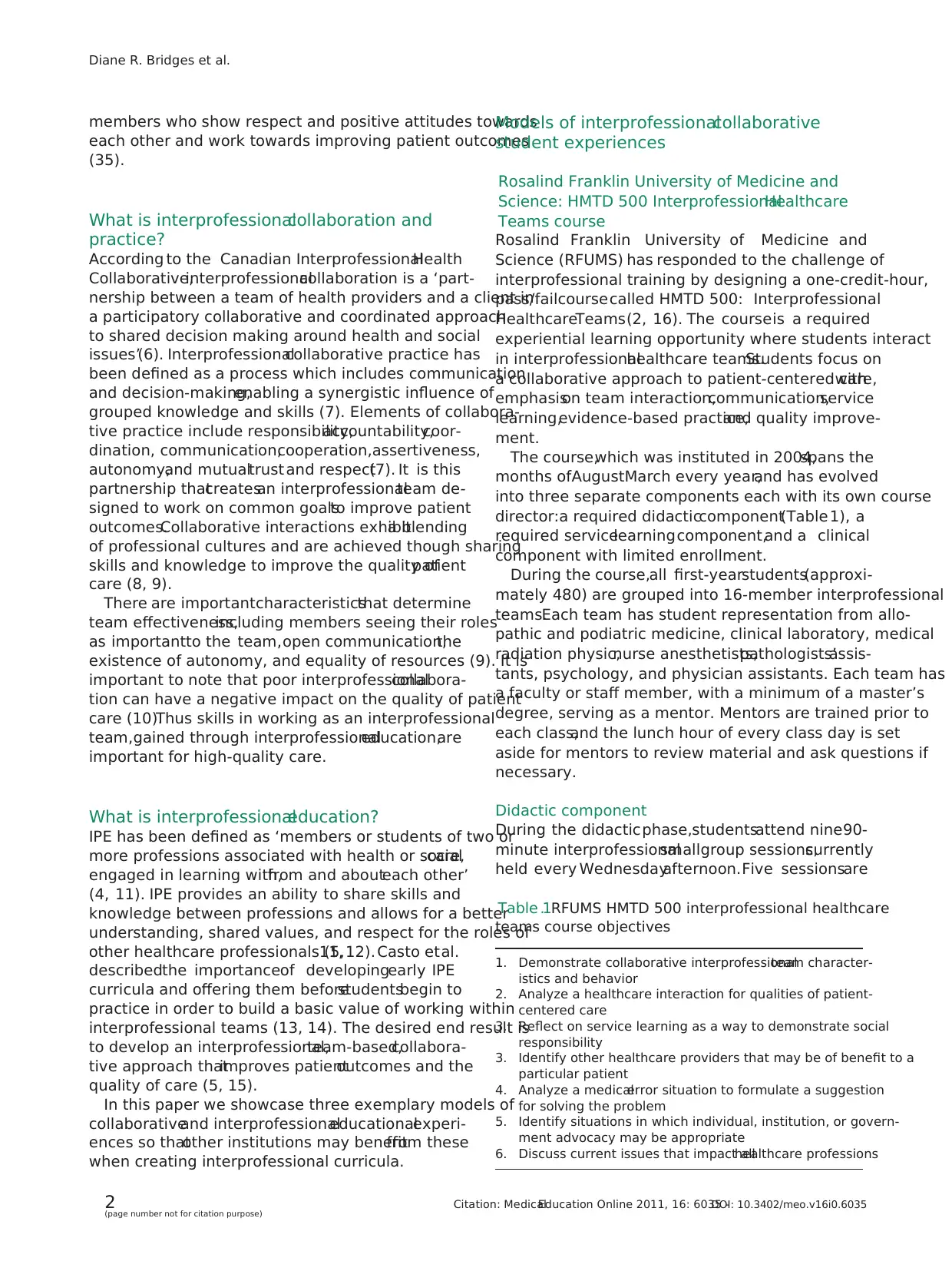

Didactic component

During the didacticphase,studentsattend nine90-

minute interprofessionalsmallgroup sessions,currently

held every Wednesdayafternoon.Five sessionsare

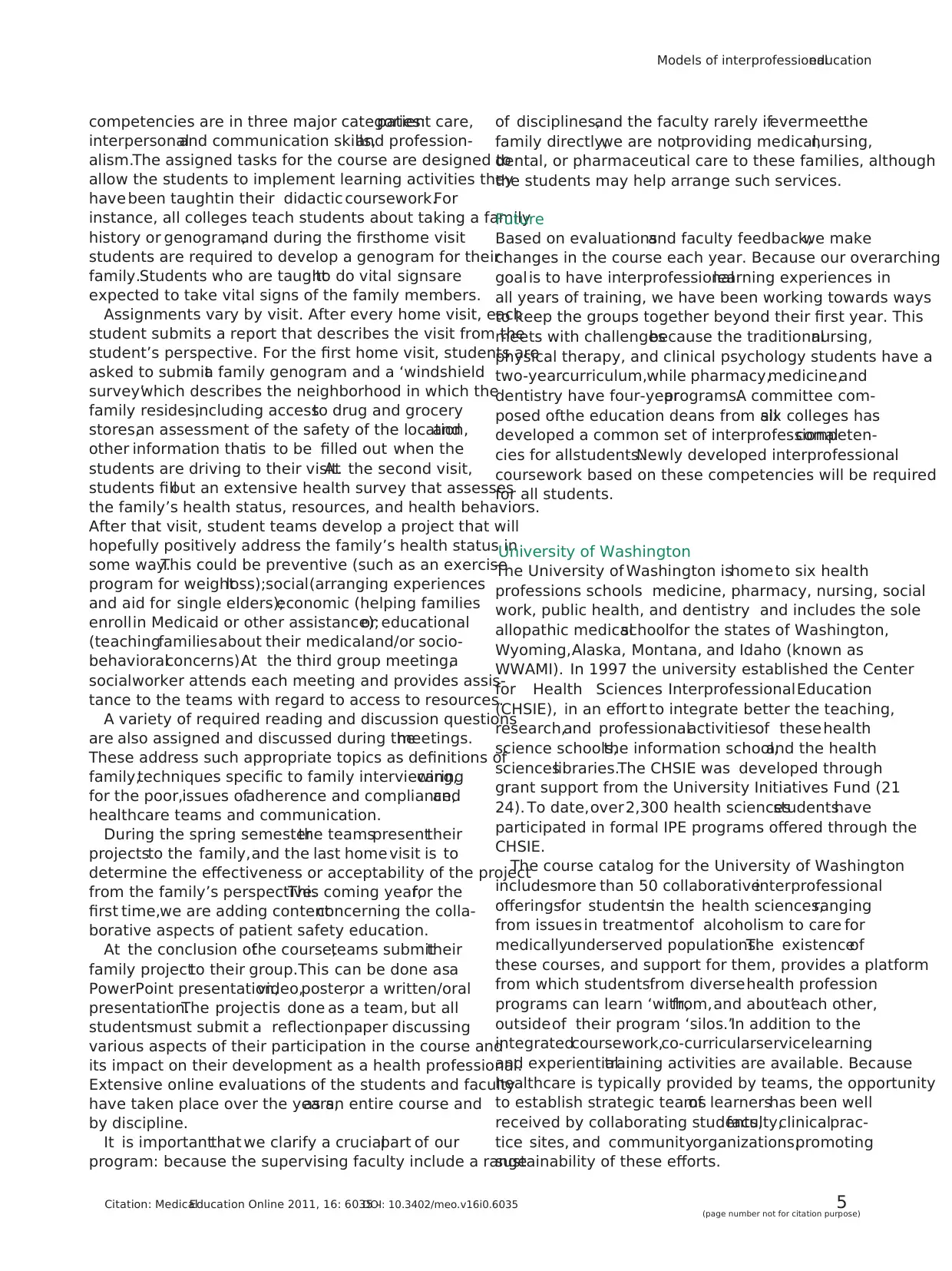

Table 1. RFUMS HMTD 500 interprofessional healthcare

teams course objectives

1. Demonstrate collaborative interprofessionalteam character-

istics and behavior

2. Analyze a healthcare interaction for qualities of patient-

centered care

3. Reflect on service learning as a way to demonstrate social

responsibility

3. Identify other healthcare providers that may be of benefit to a

particular patient

4. Analyze a medicalerror situation to formulate a suggestion

for solving the problem

5. Identify situations in which individual, institution, or govern-

ment advocacy may be appropriate

6. Discuss current issues that impact allhealthcare professions

Diane R. Bridges et al.

2(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

each other and work towards improving patient outcomes

(35).

What is interprofessionalcollaboration and

practice?

According to the Canadian InterprofessionalHealth

Collaborative,interprofessionalcollaboration is a ‘part-

nership between a team of health providers and a client in

a participatory collaborative and coordinated approach

to shared decision making around health and social

issues’(6). Interprofessionalcollaborative practice has

been defined as a process which includes communication

and decision-making,enabling a synergistic influence of

grouped knowledge and skills (7). Elements of collabora-

tive practice include responsibility,accountability,coor-

dination, communication,cooperation,assertiveness,

autonomy,and mutualtrust and respect(7). It is this

partnership thatcreatesan interprofessionalteam de-

signed to work on common goalsto improve patient

outcomes.Collaborative interactions exhibita blending

of professional cultures and are achieved though sharing

skills and knowledge to improve the quality ofpatient

care (8, 9).

There are importantcharacteristicsthat determine

team effectiveness,including members seeing their roles

as importantto the team,open communication,the

existence of autonomy, and equality of resources (9). It is

important to note that poor interprofessionalcollabora-

tion can have a negative impact on the quality of patient

care (10).Thus skills in working as an interprofessional

team,gained through interprofessionaleducation,are

important for high-quality care.

What is interprofessionaleducation?

IPE has been defined as ‘members or students of two or

more professions associated with health or socialcare,

engaged in learning with,from and abouteach other’

(4, 11). IPE provides an ability to share skills and

knowledge between professions and allows for a better

understanding, shared values, and respect for the roles of

other healthcare professionals (5,11, 12). Casto etal.

describedthe importanceof developingearly IPE

curricula and offering them beforestudentsbegin to

practice in order to build a basic value of working within

interprofessional teams (13, 14). The desired end result is

to develop an interprofessional,team-based,collabora-

tive approach thatimproves patientoutcomes and the

quality of care (5, 15).

In this paper we showcase three exemplary models of

collaborativeand interprofessionaleducationalexperi-

ences so thatother institutions may benefitfrom these

when creating interprofessional curricula.

Models of interprofessionalcollaborative

student experiences

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science: HMTD 500 InterprofessionalHealthcare

Teams course

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and

Science (RFUMS) has responded to the challenge of

interprofessional training by designing a one-credit-hour,

pass/failcoursecalled HMTD 500: Interprofessional

HealthcareTeams(2, 16). The courseis a required

experiential learning opportunity where students interact

in interprofessionalhealthcare teams.Students focus on

a collaborative approach to patient-centered care,with

emphasison team interaction,communication,service

learning,evidence-based practice,and quality improve-

ment.

The course,which was instituted in 2004,spans the

months ofAugustMarch every year,and has evolved

into three separate components each with its own course

director:a required didacticcomponent(Table 1), a

required servicelearningcomponent,and a clinical

component with limited enrollment.

During the course,all first-yearstudents(approxi-

mately 480) are grouped into 16-member interprofessional

teams.Each team has student representation from allo-

pathic and podiatric medicine, clinical laboratory, medical

radiation physic,nurse anesthetists,pathologists’assis-

tants, psychology, and physician assistants. Each team has

a faculty or staff member, with a minimum of a master’s

degree, serving as a mentor. Mentors are trained prior to

each class,and the lunch hour of every class day is set

aside for mentors to review material and ask questions if

necessary.

Didactic component

During the didacticphase,studentsattend nine90-

minute interprofessionalsmallgroup sessions,currently

held every Wednesdayafternoon.Five sessionsare

Table 1. RFUMS HMTD 500 interprofessional healthcare

teams course objectives

1. Demonstrate collaborative interprofessionalteam character-

istics and behavior

2. Analyze a healthcare interaction for qualities of patient-

centered care

3. Reflect on service learning as a way to demonstrate social

responsibility

3. Identify other healthcare providers that may be of benefit to a

particular patient

4. Analyze a medicalerror situation to formulate a suggestion

for solving the problem

5. Identify situations in which individual, institution, or govern-

ment advocacy may be appropriate

6. Discuss current issues that impact allhealthcare professions

Diane R. Bridges et al.

2(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

devoted to thelearning conceptsof interprofessional

healthcareteams,collaborativepatient-centeredcare

(functioning asa collaborative team),service learning

and county health assessment,healthcare professions (a

time to learn abouttheir own health profession),and

error cases and advocacy.

The remaining sessionsare setaside fordiscussion,

preparation,presentations,and celebrations of achieve-

ments. Student objectives, case studies, and role-play are

used to developdiscussion.Two different students

volunteer each session to moderate the class to develop

their own leadershipand communicationskills. All

course materials are loaded into our information man-

agement learning system.

Service learning component

Students are tasked with working as an interprofessional

team to identify a community partner and engage in a

community serviceproject.Each team is expected to

perform a service learning project.One of the original

five sessions is designed to allow students time together to

discussideasfor their projects.Studentsassesslocal

community needs in their didactic phase and are given a

list of community projects performed in the past to help

them decide on a projectand partner.Two additional

sessionsallow them to plan theirprojectsand subse-

quently design a posterwhich showcasestheir service

learning experience and reflection.The focus of student

projects is prevention education in the form of physical

fitness training, nutrition education, health screening, or

instruction in making healthy choices.

Service learning allots time for students to process what

they learned abouttheir community:how their knowl-

edge was used to help meet the needs of the community

and how they better understand them as a result of this

activity (17). All HMTD 500 studentscompletea

reflection form.

The last session of the course culminates each year with

a group reflection and a celebration poster day where our

community partners are invited to visit the university to

review the work our students have accomplished.Com-

munity partners see posters created by each team and are

invited to join their student groups to reflectupon the

service learning project and share with the students how

the project impacted their organization.

The collaborative interprofessionalprevention educa-

tion service learning projects have been very rewarding

and well accepted byour communitypartnersand

students,as noted by student surveys and focus groups

and awardsreceived from somecommunity partners.

Student attitudes were positive regarding this aspect of

the course.Post-course survey indicated a majority of

respondents agreed or strongly agreed with statements

regarding collaboration,teamwork,socialresponsibility,

and diversity (18).

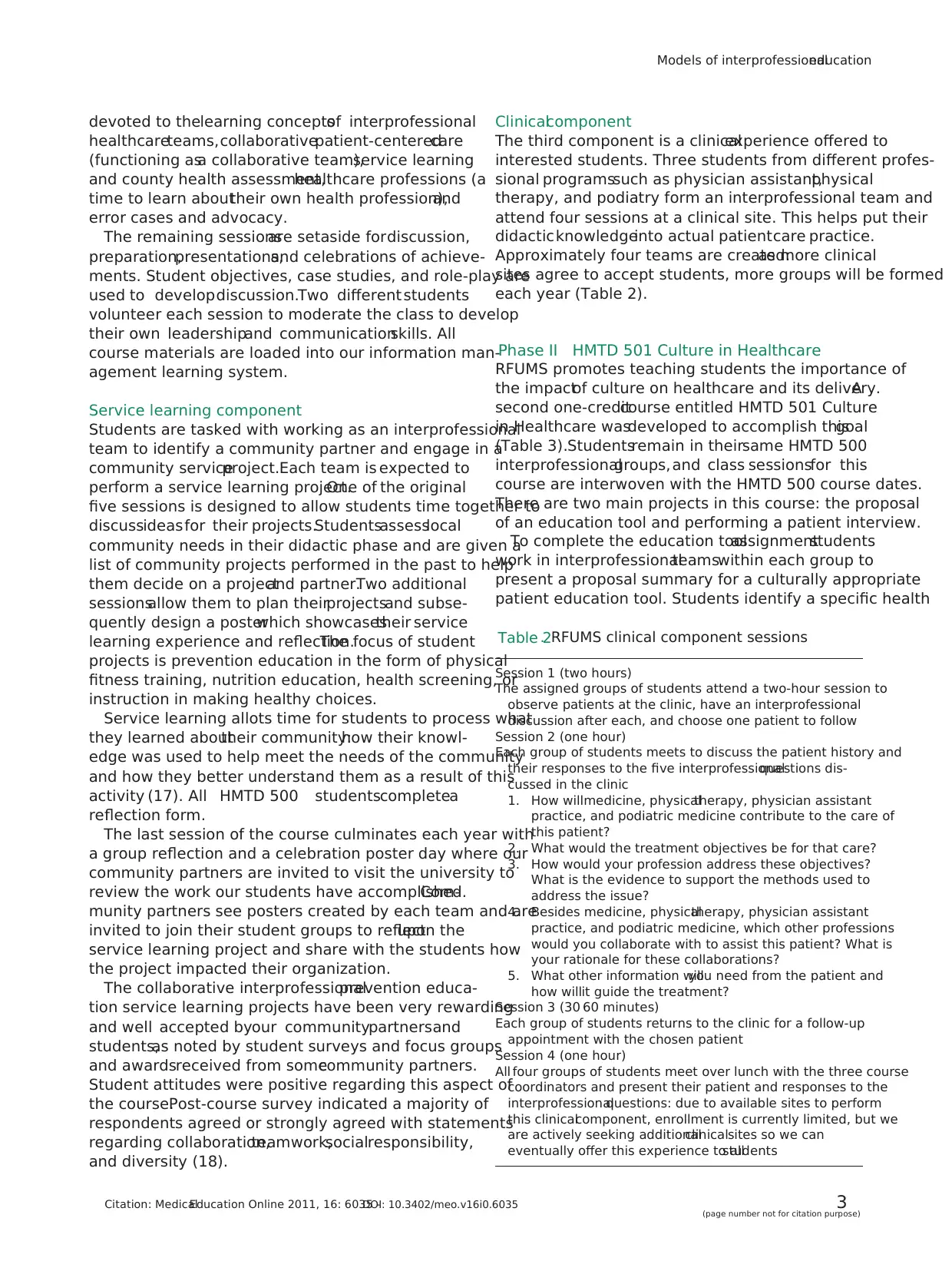

Clinicalcomponent

The third component is a clinicalexperience offered to

interested students. Three students from different profes-

sional programssuch as physician assistant,physical

therapy, and podiatry form an interprofessional team and

attend four sessions at a clinical site. This helps put their

didacticknowledgeinto actual patientcare practice.

Approximately four teams are created:as more clinical

sites agree to accept students, more groups will be formed

each year (Table 2).

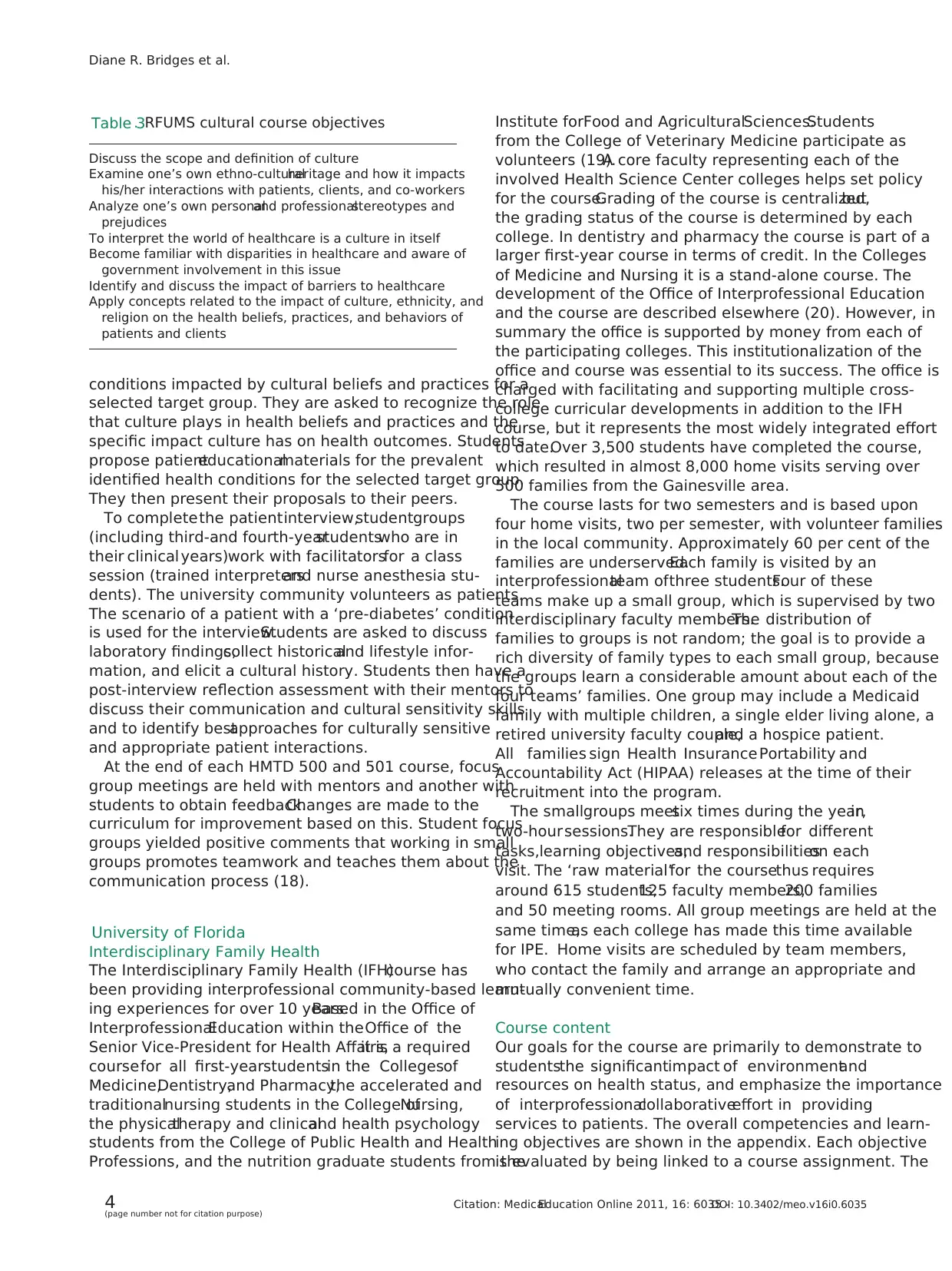

Phase II HMTD 501 Culture in Healthcare

RFUMS promotes teaching students the importance of

the impactof culture on healthcare and its delivery.A

second one-creditcourse entitled HMTD 501 Culture

in Healthcare wasdeveloped to accomplish thisgoal

(Table 3).Studentsremain in theirsame HMTD 500

interprofessionalgroups,and class sessionsfor this

course are interwoven with the HMTD 500 course dates.

There are two main projects in this course: the proposal

of an education tool and performing a patient interview.

To complete the education toolassignmentstudents

work in interprofessionalteamswithin each group to

present a proposal summary for a culturally appropriate

patient education tool. Students identify a specific health

Table 2. RFUMS clinical component sessions

Session 1 (two hours)

The assigned groups of students attend a two-hour session to

observe patients at the clinic, have an interprofessional

discussion after each, and choose one patient to follow

Session 2 (one hour)

Each group of students meets to discuss the patient history and

their responses to the five interprofessionalquestions dis-

cussed in the clinic

1. How willmedicine, physicaltherapy, physician assistant

practice, and podiatric medicine contribute to the care of

this patient?

2. What would the treatment objectives be for that care?

3. How would your profession address these objectives?

What is the evidence to support the methods used to

address the issue?

4. Besides medicine, physicaltherapy, physician assistant

practice, and podiatric medicine, which other professions

would you collaborate with to assist this patient? What is

your rationale for these collaborations?

5. What other information willyou need from the patient and

how willit guide the treatment?

Session 3 (30 60 minutes)

Each group of students returns to the clinic for a follow-up

appointment with the chosen patient

Session 4 (one hour)

All four groups of students meet over lunch with the three course

coordinators and present their patient and responses to the

interprofessionalquestions: due to available sites to perform

this clinicalcomponent, enrollment is currently limited, but we

are actively seeking additionalclinicalsites so we can

eventually offer this experience to allstudents

Models of interprofessionaleducation

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 3(page number not for citation purpose)

healthcareteams,collaborativepatient-centeredcare

(functioning asa collaborative team),service learning

and county health assessment,healthcare professions (a

time to learn abouttheir own health profession),and

error cases and advocacy.

The remaining sessionsare setaside fordiscussion,

preparation,presentations,and celebrations of achieve-

ments. Student objectives, case studies, and role-play are

used to developdiscussion.Two different students

volunteer each session to moderate the class to develop

their own leadershipand communicationskills. All

course materials are loaded into our information man-

agement learning system.

Service learning component

Students are tasked with working as an interprofessional

team to identify a community partner and engage in a

community serviceproject.Each team is expected to

perform a service learning project.One of the original

five sessions is designed to allow students time together to

discussideasfor their projects.Studentsassesslocal

community needs in their didactic phase and are given a

list of community projects performed in the past to help

them decide on a projectand partner.Two additional

sessionsallow them to plan theirprojectsand subse-

quently design a posterwhich showcasestheir service

learning experience and reflection.The focus of student

projects is prevention education in the form of physical

fitness training, nutrition education, health screening, or

instruction in making healthy choices.

Service learning allots time for students to process what

they learned abouttheir community:how their knowl-

edge was used to help meet the needs of the community

and how they better understand them as a result of this

activity (17). All HMTD 500 studentscompletea

reflection form.

The last session of the course culminates each year with

a group reflection and a celebration poster day where our

community partners are invited to visit the university to

review the work our students have accomplished.Com-

munity partners see posters created by each team and are

invited to join their student groups to reflectupon the

service learning project and share with the students how

the project impacted their organization.

The collaborative interprofessionalprevention educa-

tion service learning projects have been very rewarding

and well accepted byour communitypartnersand

students,as noted by student surveys and focus groups

and awardsreceived from somecommunity partners.

Student attitudes were positive regarding this aspect of

the course.Post-course survey indicated a majority of

respondents agreed or strongly agreed with statements

regarding collaboration,teamwork,socialresponsibility,

and diversity (18).

Clinicalcomponent

The third component is a clinicalexperience offered to

interested students. Three students from different profes-

sional programssuch as physician assistant,physical

therapy, and podiatry form an interprofessional team and

attend four sessions at a clinical site. This helps put their

didacticknowledgeinto actual patientcare practice.

Approximately four teams are created:as more clinical

sites agree to accept students, more groups will be formed

each year (Table 2).

Phase II HMTD 501 Culture in Healthcare

RFUMS promotes teaching students the importance of

the impactof culture on healthcare and its delivery.A

second one-creditcourse entitled HMTD 501 Culture

in Healthcare wasdeveloped to accomplish thisgoal

(Table 3).Studentsremain in theirsame HMTD 500

interprofessionalgroups,and class sessionsfor this

course are interwoven with the HMTD 500 course dates.

There are two main projects in this course: the proposal

of an education tool and performing a patient interview.

To complete the education toolassignmentstudents

work in interprofessionalteamswithin each group to

present a proposal summary for a culturally appropriate

patient education tool. Students identify a specific health

Table 2. RFUMS clinical component sessions

Session 1 (two hours)

The assigned groups of students attend a two-hour session to

observe patients at the clinic, have an interprofessional

discussion after each, and choose one patient to follow

Session 2 (one hour)

Each group of students meets to discuss the patient history and

their responses to the five interprofessionalquestions dis-

cussed in the clinic

1. How willmedicine, physicaltherapy, physician assistant

practice, and podiatric medicine contribute to the care of

this patient?

2. What would the treatment objectives be for that care?

3. How would your profession address these objectives?

What is the evidence to support the methods used to

address the issue?

4. Besides medicine, physicaltherapy, physician assistant

practice, and podiatric medicine, which other professions

would you collaborate with to assist this patient? What is

your rationale for these collaborations?

5. What other information willyou need from the patient and

how willit guide the treatment?

Session 3 (30 60 minutes)

Each group of students returns to the clinic for a follow-up

appointment with the chosen patient

Session 4 (one hour)

All four groups of students meet over lunch with the three course

coordinators and present their patient and responses to the

interprofessionalquestions: due to available sites to perform

this clinicalcomponent, enrollment is currently limited, but we

are actively seeking additionalclinicalsites so we can

eventually offer this experience to allstudents

Models of interprofessionaleducation

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 3(page number not for citation purpose)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

conditions impacted by cultural beliefs and practices for a

selected target group. They are asked to recognize the role

that culture plays in health beliefs and practices and the

specific impact culture has on health outcomes. Students

propose patienteducationalmaterials for the prevalent

identified health conditions for the selected target group.

They then present their proposals to their peers.

To completethe patientinterview,studentgroups

(including third-and fourth-yearstudentswho are in

their clinical years)work with facilitatorsfor a class

session (trained interpretersand nurse anesthesia stu-

dents). The university community volunteers as patients.

The scenario of a patient with a ‘pre-diabetes’ condition

is used for the interview.Students are asked to discuss

laboratory findings,collect historicaland lifestyle infor-

mation, and elicit a cultural history. Students then have a

post-interview reflection assessment with their mentors to

discuss their communication and cultural sensitivity skills

and to identify bestapproaches for culturally sensitive

and appropriate patient interactions.

At the end of each HMTD 500 and 501 course, focus

group meetings are held with mentors and another with

students to obtain feedback.Changes are made to the

curriculum for improvement based on this. Student focus

groups yielded positive comments that working in small

groups promotes teamwork and teaches them about the

communication process (18).

University of Florida

Interdisciplinary Family Health

The Interdisciplinary Family Health (IFH)course has

been providing interprofessional community-based learn-

ing experiences for over 10 years.Based in the Office of

InterprofessionalEducation within theOffice of the

Senior Vice-President for Health Affairs,it is a required

coursefor all first-yearstudentsin the Collegesof

Medicine,Dentistry,and Pharmacy,the accelerated and

traditionalnursing students in the College ofNursing,

the physicaltherapy and clinicaland health psychology

students from the College of Public Health and Health

Professions, and the nutrition graduate students from the

Institute forFood and AgriculturalSciences.Students

from the College of Veterinary Medicine participate as

volunteers (19).A core faculty representing each of the

involved Health Science Center colleges helps set policy

for the course.Grading of the course is centralized,but

the grading status of the course is determined by each

college. In dentistry and pharmacy the course is part of a

larger first-year course in terms of credit. In the Colleges

of Medicine and Nursing it is a stand-alone course. The

development of the Office of Interprofessional Education

and the course are described elsewhere (20). However, in

summary the office is supported by money from each of

the participating colleges. This institutionalization of the

office and course was essential to its success. The office is

charged with facilitating and supporting multiple cross-

college curricular developments in addition to the IFH

course, but it represents the most widely integrated effort

to date.Over 3,500 students have completed the course,

which resulted in almost 8,000 home visits serving over

500 families from the Gainesville area.

The course lasts for two semesters and is based upon

four home visits, two per semester, with volunteer families

in the local community. Approximately 60 per cent of the

families are underserved.Each family is visited by an

interprofessionalteam ofthree students.Four of these

teams make up a small group, which is supervised by two

interdisciplinary faculty members.The distribution of

families to groups is not random; the goal is to provide a

rich diversity of family types to each small group, because

the groups learn a considerable amount about each of the

four teams’ families. One group may include a Medicaid

family with multiple children, a single elder living alone, a

retired university faculty couple,and a hospice patient.

All families sign Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) releases at the time of their

recruitment into the program.

The smallgroups meetsix times during the year,in

two-hour sessions.They are responsiblefor different

tasks,learning objectives,and responsibilitieson each

visit. The ‘raw material’for the coursethus requires

around 615 students,125 faculty members,200 families

and 50 meeting rooms. All group meetings are held at the

same time,as each college has made this time available

for IPE. Home visits are scheduled by team members,

who contact the family and arrange an appropriate and

mutually convenient time.

Course content

Our goals for the course are primarily to demonstrate to

studentsthe significantimpact of environmentand

resources on health status, and emphasize the importance

of interprofessionalcollaborativeeffort in providing

services to patients. The overall competencies and learn-

ing objectives are shown in the appendix. Each objective

is evaluated by being linked to a course assignment. The

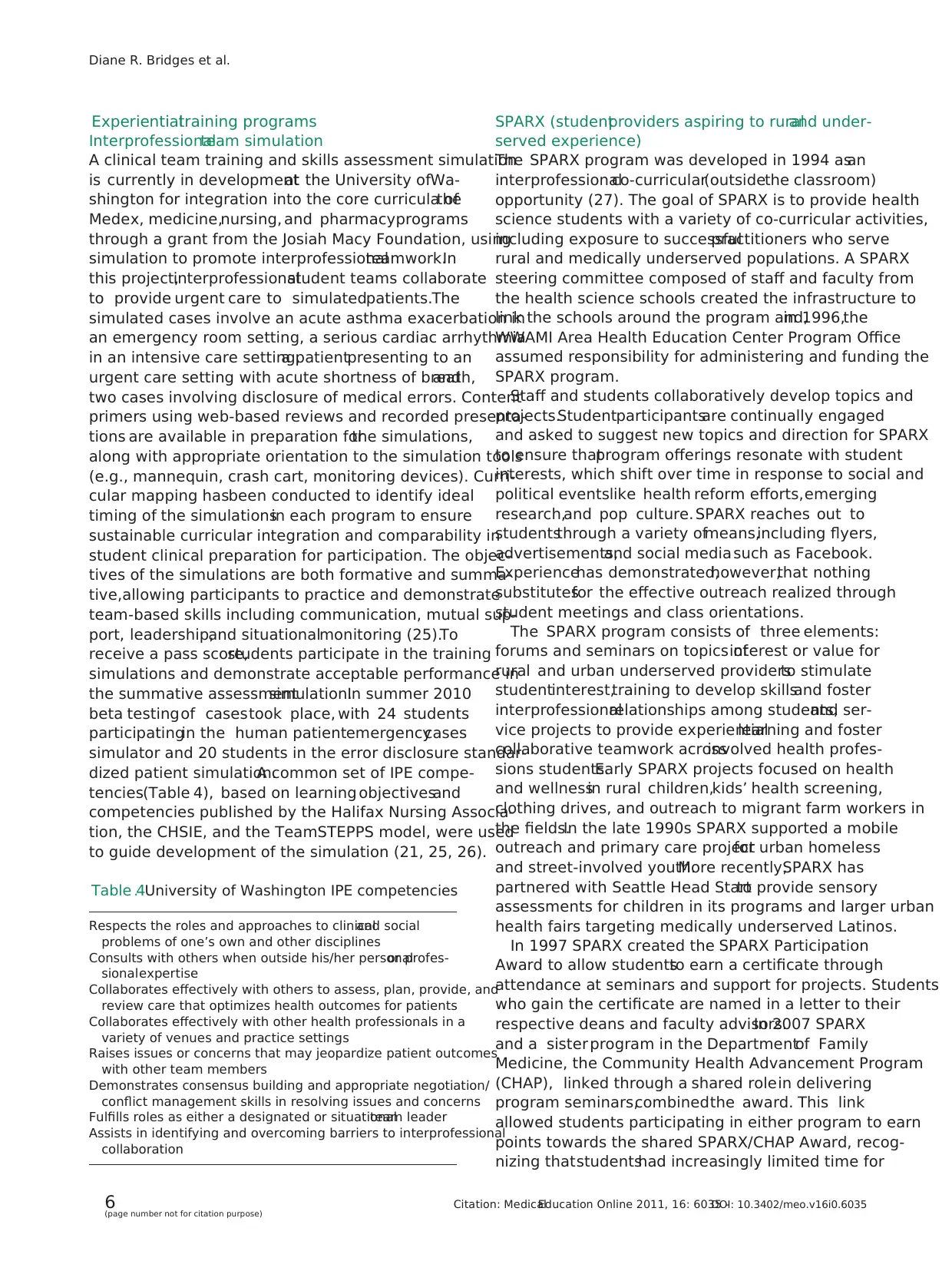

Table 3. RFUMS cultural course objectives

Discuss the scope and definition of culture

Examine one’s own ethno-culturalheritage and how it impacts

his/her interactions with patients, clients, and co-workers

Analyze one’s own personaland professionalstereotypes and

prejudices

To interpret the world of healthcare is a culture in itself

Become familiar with disparities in healthcare and aware of

government involvement in this issue

Identify and discuss the impact of barriers to healthcare

Apply concepts related to the impact of culture, ethnicity, and

religion on the health beliefs, practices, and behaviors of

patients and clients

Diane R. Bridges et al.

4(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

selected target group. They are asked to recognize the role

that culture plays in health beliefs and practices and the

specific impact culture has on health outcomes. Students

propose patienteducationalmaterials for the prevalent

identified health conditions for the selected target group.

They then present their proposals to their peers.

To completethe patientinterview,studentgroups

(including third-and fourth-yearstudentswho are in

their clinical years)work with facilitatorsfor a class

session (trained interpretersand nurse anesthesia stu-

dents). The university community volunteers as patients.

The scenario of a patient with a ‘pre-diabetes’ condition

is used for the interview.Students are asked to discuss

laboratory findings,collect historicaland lifestyle infor-

mation, and elicit a cultural history. Students then have a

post-interview reflection assessment with their mentors to

discuss their communication and cultural sensitivity skills

and to identify bestapproaches for culturally sensitive

and appropriate patient interactions.

At the end of each HMTD 500 and 501 course, focus

group meetings are held with mentors and another with

students to obtain feedback.Changes are made to the

curriculum for improvement based on this. Student focus

groups yielded positive comments that working in small

groups promotes teamwork and teaches them about the

communication process (18).

University of Florida

Interdisciplinary Family Health

The Interdisciplinary Family Health (IFH)course has

been providing interprofessional community-based learn-

ing experiences for over 10 years.Based in the Office of

InterprofessionalEducation within theOffice of the

Senior Vice-President for Health Affairs,it is a required

coursefor all first-yearstudentsin the Collegesof

Medicine,Dentistry,and Pharmacy,the accelerated and

traditionalnursing students in the College ofNursing,

the physicaltherapy and clinicaland health psychology

students from the College of Public Health and Health

Professions, and the nutrition graduate students from the

Institute forFood and AgriculturalSciences.Students

from the College of Veterinary Medicine participate as

volunteers (19).A core faculty representing each of the

involved Health Science Center colleges helps set policy

for the course.Grading of the course is centralized,but

the grading status of the course is determined by each

college. In dentistry and pharmacy the course is part of a

larger first-year course in terms of credit. In the Colleges

of Medicine and Nursing it is a stand-alone course. The

development of the Office of Interprofessional Education

and the course are described elsewhere (20). However, in

summary the office is supported by money from each of

the participating colleges. This institutionalization of the

office and course was essential to its success. The office is

charged with facilitating and supporting multiple cross-

college curricular developments in addition to the IFH

course, but it represents the most widely integrated effort

to date.Over 3,500 students have completed the course,

which resulted in almost 8,000 home visits serving over

500 families from the Gainesville area.

The course lasts for two semesters and is based upon

four home visits, two per semester, with volunteer families

in the local community. Approximately 60 per cent of the

families are underserved.Each family is visited by an

interprofessionalteam ofthree students.Four of these

teams make up a small group, which is supervised by two

interdisciplinary faculty members.The distribution of

families to groups is not random; the goal is to provide a

rich diversity of family types to each small group, because

the groups learn a considerable amount about each of the

four teams’ families. One group may include a Medicaid

family with multiple children, a single elder living alone, a

retired university faculty couple,and a hospice patient.

All families sign Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) releases at the time of their

recruitment into the program.

The smallgroups meetsix times during the year,in

two-hour sessions.They are responsiblefor different

tasks,learning objectives,and responsibilitieson each

visit. The ‘raw material’for the coursethus requires

around 615 students,125 faculty members,200 families

and 50 meeting rooms. All group meetings are held at the

same time,as each college has made this time available

for IPE. Home visits are scheduled by team members,

who contact the family and arrange an appropriate and

mutually convenient time.

Course content

Our goals for the course are primarily to demonstrate to

studentsthe significantimpact of environmentand

resources on health status, and emphasize the importance

of interprofessionalcollaborativeeffort in providing

services to patients. The overall competencies and learn-

ing objectives are shown in the appendix. Each objective

is evaluated by being linked to a course assignment. The

Table 3. RFUMS cultural course objectives

Discuss the scope and definition of culture

Examine one’s own ethno-culturalheritage and how it impacts

his/her interactions with patients, clients, and co-workers

Analyze one’s own personaland professionalstereotypes and

prejudices

To interpret the world of healthcare is a culture in itself

Become familiar with disparities in healthcare and aware of

government involvement in this issue

Identify and discuss the impact of barriers to healthcare

Apply concepts related to the impact of culture, ethnicity, and

religion on the health beliefs, practices, and behaviors of

patients and clients

Diane R. Bridges et al.

4(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

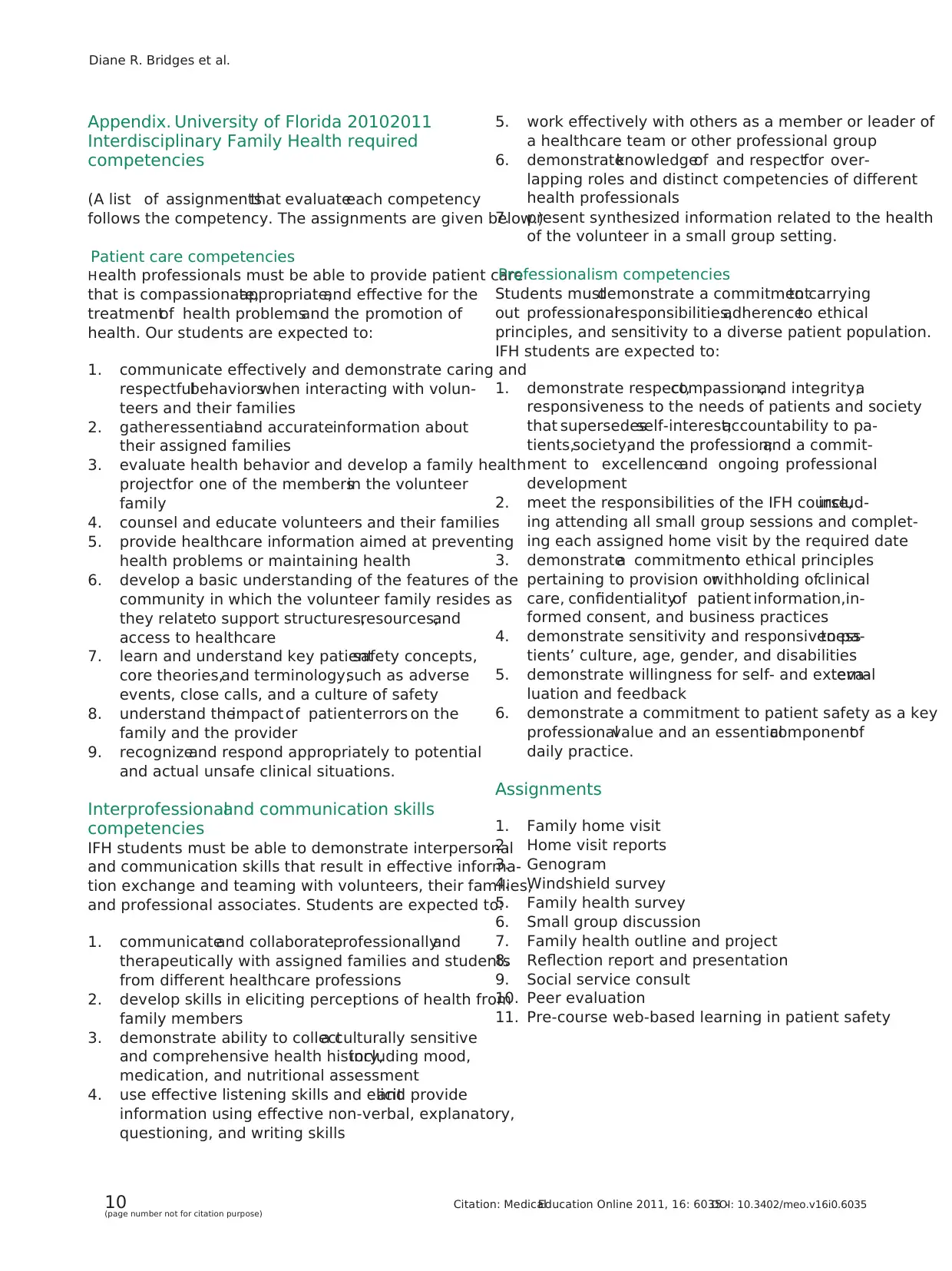

competencies are in three major categories:patient care,

interpersonaland communication skills,and profession-

alism.The assigned tasks for the course are designed to

allow the students to implement learning activities they

have been taughtin their didactic coursework.For

instance, all colleges teach students about taking a family

history or genogram,and during the firsthome visit

students are required to develop a genogram for their

family.Students who are taughtto do vital signsare

expected to take vital signs of the family members.

Assignments vary by visit. After every home visit, each

student submits a report that describes the visit from the

student’s perspective. For the first home visit, students are

asked to submita family genogram and a ‘windshield

survey’which describes the neighborhood in which the

family resides,including accessto drug and grocery

stores,an assessment of the safety of the location,and

other information thatis to be filled out when the

students are driving to their visit.At the second visit,

students fillout an extensive health survey that assesses

the family’s health status, resources, and health behaviors.

After that visit, student teams develop a project that will

hopefully positively address the family’s health status in

some way.This could be preventive (such as an exercise

program for weightloss);social(arranging experiences

and aid for single elders);economic (helping families

enrollin Medicaid or other assistance);or educational

(teachingfamiliesabout their medicaland/or socio-

behavioralconcerns).At the third group meeting,a

socialworker attends each meeting and provides assis-

tance to the teams with regard to access to resources.

A variety of required reading and discussion questions

are also assigned and discussed during themeetings.

These address such appropriate topics as definitions of

family,techniques specific to family interviewing,caring

for the poor,issues ofadherence and compliance,and

healthcare teams and communication.

During the spring semesterthe teamspresenttheir

projectsto the family,and the last home visit is to

determine the effectiveness or acceptability of the project

from the family’s perspective.This coming year,for the

first time,we are adding contentconcerning the colla-

borative aspects of patient safety education.

At the conclusion ofthe course,teams submittheir

family projectto their group.This can be done asa

PowerPoint presentation,video,poster,or a written/oral

presentation.The projectis done as a team, but all

studentsmust submit a reflectionpaper discussing

various aspects of their participation in the course and

its impact on their development as a health professional.

Extensive online evaluations of the students and faculty

have taken place over the years,as an entire course and

by discipline.

It is importantthat we clarify a crucialpart of our

program: because the supervising faculty include a range

of disciplines,and the faculty rarely ifevermeetthe

family directly,we are notproviding medical,nursing,

dental, or pharmaceutical care to these families, although

the students may help arrange such services.

Future

Based on evaluationsand faculty feedback,we make

changes in the course each year. Because our overarching

goalis to have interprofessionallearning experiences in

all years of training, we have been working towards ways

to keep the groups together beyond their first year. This

meets with challengesbecause the traditionalnursing,

physical therapy, and clinical psychology students have a

two-yearcurriculum,while pharmacy,medicine,and

dentistry have four-yearprograms.A committee com-

posed ofthe education deans from allsix colleges has

developed a common set of interprofessionalcompeten-

cies for allstudents.Newly developed interprofessional

coursework based on these competencies will be required

for all students.

University of Washington

The University of Washington ishome to six health

professions schools medicine, pharmacy, nursing, social

work, public health, and dentistry and includes the sole

allopathic medicalschoolfor the states of Washington,

Wyoming,Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (known as

WWAMI). In 1997 the university established the Center

for Health Sciences InterprofessionalEducation

(CHSIE), in an effort to integrate better the teaching,

research,and professionalactivitiesof these health

science schools,the information school,and the health

scienceslibraries.The CHSIE was developed through

grant support from the University Initiatives Fund (21

24). To date,over2,300 health sciencesstudentshave

participated in formal IPE programs offered through the

CHSIE.

The course catalog for the University of Washington

includesmore than 50 collaborativeinterprofessional

offeringsfor studentsin the health sciences,ranging

from issues in treatmentof alcoholism to care for

medicallyunderserved populations.The existenceof

these courses, and support for them, provides a platform

from which studentsfrom diversehealth profession

programs can learn ‘with,from,and about’each other,

outsideof their program ‘silos.’In addition to the

integratedcoursework,co-curricularservicelearning

and experientialtraining activities are available. Because

healthcare is typically provided by teams, the opportunity

to establish strategic teamsof learnershas been well

received by collaborating students,faculty,clinicalprac-

tice sites, and communityorganizations,promoting

sustainability of these efforts.

Models of interprofessionaleducation

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 5(page number not for citation purpose)

interpersonaland communication skills,and profession-

alism.The assigned tasks for the course are designed to

allow the students to implement learning activities they

have been taughtin their didactic coursework.For

instance, all colleges teach students about taking a family

history or genogram,and during the firsthome visit

students are required to develop a genogram for their

family.Students who are taughtto do vital signsare

expected to take vital signs of the family members.

Assignments vary by visit. After every home visit, each

student submits a report that describes the visit from the

student’s perspective. For the first home visit, students are

asked to submita family genogram and a ‘windshield

survey’which describes the neighborhood in which the

family resides,including accessto drug and grocery

stores,an assessment of the safety of the location,and

other information thatis to be filled out when the

students are driving to their visit.At the second visit,

students fillout an extensive health survey that assesses

the family’s health status, resources, and health behaviors.

After that visit, student teams develop a project that will

hopefully positively address the family’s health status in

some way.This could be preventive (such as an exercise

program for weightloss);social(arranging experiences

and aid for single elders);economic (helping families

enrollin Medicaid or other assistance);or educational

(teachingfamiliesabout their medicaland/or socio-

behavioralconcerns).At the third group meeting,a

socialworker attends each meeting and provides assis-

tance to the teams with regard to access to resources.

A variety of required reading and discussion questions

are also assigned and discussed during themeetings.

These address such appropriate topics as definitions of

family,techniques specific to family interviewing,caring

for the poor,issues ofadherence and compliance,and

healthcare teams and communication.

During the spring semesterthe teamspresenttheir

projectsto the family,and the last home visit is to

determine the effectiveness or acceptability of the project

from the family’s perspective.This coming year,for the

first time,we are adding contentconcerning the colla-

borative aspects of patient safety education.

At the conclusion ofthe course,teams submittheir

family projectto their group.This can be done asa

PowerPoint presentation,video,poster,or a written/oral

presentation.The projectis done as a team, but all

studentsmust submit a reflectionpaper discussing

various aspects of their participation in the course and

its impact on their development as a health professional.

Extensive online evaluations of the students and faculty

have taken place over the years,as an entire course and

by discipline.

It is importantthat we clarify a crucialpart of our

program: because the supervising faculty include a range

of disciplines,and the faculty rarely ifevermeetthe

family directly,we are notproviding medical,nursing,

dental, or pharmaceutical care to these families, although

the students may help arrange such services.

Future

Based on evaluationsand faculty feedback,we make

changes in the course each year. Because our overarching

goalis to have interprofessionallearning experiences in

all years of training, we have been working towards ways

to keep the groups together beyond their first year. This

meets with challengesbecause the traditionalnursing,

physical therapy, and clinical psychology students have a

two-yearcurriculum,while pharmacy,medicine,and

dentistry have four-yearprograms.A committee com-

posed ofthe education deans from allsix colleges has

developed a common set of interprofessionalcompeten-

cies for allstudents.Newly developed interprofessional

coursework based on these competencies will be required

for all students.

University of Washington

The University of Washington ishome to six health

professions schools medicine, pharmacy, nursing, social

work, public health, and dentistry and includes the sole

allopathic medicalschoolfor the states of Washington,

Wyoming,Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (known as

WWAMI). In 1997 the university established the Center

for Health Sciences InterprofessionalEducation

(CHSIE), in an effort to integrate better the teaching,

research,and professionalactivitiesof these health

science schools,the information school,and the health

scienceslibraries.The CHSIE was developed through

grant support from the University Initiatives Fund (21

24). To date,over2,300 health sciencesstudentshave

participated in formal IPE programs offered through the

CHSIE.

The course catalog for the University of Washington

includesmore than 50 collaborativeinterprofessional

offeringsfor studentsin the health sciences,ranging

from issues in treatmentof alcoholism to care for

medicallyunderserved populations.The existenceof

these courses, and support for them, provides a platform

from which studentsfrom diversehealth profession

programs can learn ‘with,from,and about’each other,

outsideof their program ‘silos.’In addition to the

integratedcoursework,co-curricularservicelearning

and experientialtraining activities are available. Because

healthcare is typically provided by teams, the opportunity

to establish strategic teamsof learnershas been well

received by collaborating students,faculty,clinicalprac-

tice sites, and communityorganizations,promoting

sustainability of these efforts.

Models of interprofessionaleducation

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 5(page number not for citation purpose)

Experientialtraining programs

Interprofessionalteam simulation

A clinical team training and skills assessment simulation

is currently in developmentat the University ofWa-

shington for integration into the core curricula ofthe

Medex, medicine,nursing, and pharmacyprograms

through a grant from the Josiah Macy Foundation, using

simulation to promote interprofessionalteamwork.In

this project,interprofessionalstudent teams collaborate

to provide urgent care to simulatedpatients.The

simulated cases involve an acute asthma exacerbation in

an emergency room setting, a serious cardiac arrhythmia

in an intensive care setting,a patientpresenting to an

urgent care setting with acute shortness of breath,and

two cases involving disclosure of medical errors. Content

primers using web-based reviews and recorded presenta-

tions are available in preparation forthe simulations,

along with appropriate orientation to the simulation tools

(e.g., mannequin, crash cart, monitoring devices). Curri-

cular mapping hasbeen conducted to identify ideal

timing of the simulationsin each program to ensure

sustainable curricular integration and comparability in

student clinical preparation for participation. The objec-

tives of the simulations are both formative and summa-

tive,allowing participants to practice and demonstrate

team-based skills including communication, mutual sup-

port, leadership,and situationalmonitoring (25).To

receive a pass score,students participate in the training

simulations and demonstrate acceptable performance in

the summative assessmentsimulation.In summer 2010

beta testingof casestook place, with 24 students

participatingin the human patientemergencycases

simulator and 20 students in the error disclosure standar-

dized patient simulation.A common set of IPE compe-

tencies(Table 4), based on learning objectivesand

competencies published by the Halifax Nursing Associa-

tion, the CHSIE, and the TeamSTEPPS model, were used

to guide development of the simulation (21, 25, 26).

SPARX (studentproviders aspiring to ruraland under-

served experience)

The SPARX program was developed in 1994 asan

interprofessionalco-curricular(outsidethe classroom)

opportunity (27). The goal of SPARX is to provide health

science students with a variety of co-curricular activities,

including exposure to successfulpractitioners who serve

rural and medically underserved populations. A SPARX

steering committee composed of staff and faculty from

the health science schools created the infrastructure to

link the schools around the program and,in 1996,the

WWAMI Area Health Education Center Program Office

assumed responsibility for administering and funding the

SPARX program.

Staff and students collaboratively develop topics and

projects.Studentparticipantsare continually engaged

and asked to suggest new topics and direction for SPARX

to ensure thatprogram offerings resonate with student

interests, which shift over time in response to social and

political eventslike health reform efforts,emerging

research,and pop culture. SPARX reaches out to

studentsthrough a variety ofmeans,including flyers,

advertisements,and social media such as Facebook.

Experiencehas demonstrated,however,that nothing

substitutesfor the effective outreach realized through

student meetings and class orientations.

The SPARX program consists of three elements:

forums and seminars on topics ofinterest or value for

rural and urban underserved providersto stimulate

studentinterest,training to develop skillsand foster

interprofessionalrelationships among students,and ser-

vice projects to provide experientiallearning and foster

collaborative teamwork acrossinvolved health profes-

sions students.Early SPARX projects focused on health

and wellnessin rural children,kids’ health screening,

clothing drives, and outreach to migrant farm workers in

the fields.In the late 1990s SPARX supported a mobile

outreach and primary care projectfor urban homeless

and street-involved youth.More recently,SPARX has

partnered with Seattle Head Startto provide sensory

assessments for children in its programs and larger urban

health fairs targeting medically underserved Latinos.

In 1997 SPARX created the SPARX Participation

Award to allow studentsto earn a certificate through

attendance at seminars and support for projects. Students

who gain the certificate are named in a letter to their

respective deans and faculty advisors.In 2007 SPARX

and a sister program in the Departmentof Family

Medicine, the Community Health Advancement Program

(CHAP), linked through a shared rolein delivering

program seminars,combinedthe award. This link

allowed students participating in either program to earn

points towards the shared SPARX/CHAP Award, recog-

nizing thatstudentshad increasingly limited time for

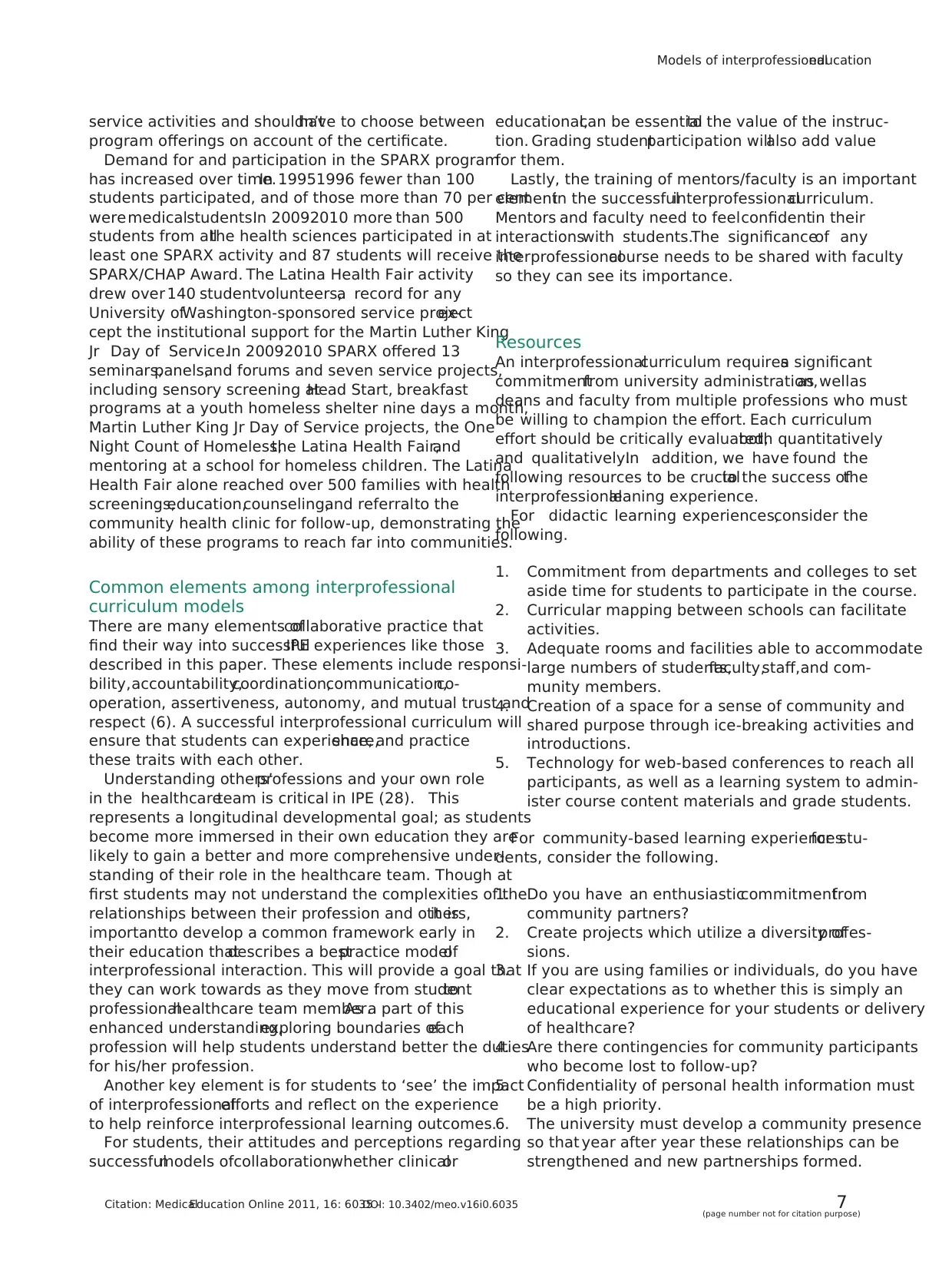

Table 4. University of Washington IPE competencies

Respects the roles and approaches to clinicaland social

problems of one’s own and other disciplines

Consults with others when outside his/her personalor profes-

sionalexpertise

Collaborates effectively with others to assess, plan, provide, and

review care that optimizes health outcomes for patients

Collaborates effectively with other health professionals in a

variety of venues and practice settings

Raises issues or concerns that may jeopardize patient outcomes

with other team members

Demonstrates consensus building and appropriate negotiation/

conflict management skills in resolving issues and concerns

Fulfills roles as either a designated or situationalteam leader

Assists in identifying and overcoming barriers to interprofessional

collaboration

Diane R. Bridges et al.

6(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

Interprofessionalteam simulation

A clinical team training and skills assessment simulation

is currently in developmentat the University ofWa-

shington for integration into the core curricula ofthe

Medex, medicine,nursing, and pharmacyprograms

through a grant from the Josiah Macy Foundation, using

simulation to promote interprofessionalteamwork.In

this project,interprofessionalstudent teams collaborate

to provide urgent care to simulatedpatients.The

simulated cases involve an acute asthma exacerbation in

an emergency room setting, a serious cardiac arrhythmia

in an intensive care setting,a patientpresenting to an

urgent care setting with acute shortness of breath,and

two cases involving disclosure of medical errors. Content

primers using web-based reviews and recorded presenta-

tions are available in preparation forthe simulations,

along with appropriate orientation to the simulation tools

(e.g., mannequin, crash cart, monitoring devices). Curri-

cular mapping hasbeen conducted to identify ideal

timing of the simulationsin each program to ensure

sustainable curricular integration and comparability in

student clinical preparation for participation. The objec-

tives of the simulations are both formative and summa-

tive,allowing participants to practice and demonstrate

team-based skills including communication, mutual sup-

port, leadership,and situationalmonitoring (25).To

receive a pass score,students participate in the training

simulations and demonstrate acceptable performance in

the summative assessmentsimulation.In summer 2010

beta testingof casestook place, with 24 students

participatingin the human patientemergencycases

simulator and 20 students in the error disclosure standar-

dized patient simulation.A common set of IPE compe-

tencies(Table 4), based on learning objectivesand

competencies published by the Halifax Nursing Associa-

tion, the CHSIE, and the TeamSTEPPS model, were used

to guide development of the simulation (21, 25, 26).

SPARX (studentproviders aspiring to ruraland under-

served experience)

The SPARX program was developed in 1994 asan

interprofessionalco-curricular(outsidethe classroom)

opportunity (27). The goal of SPARX is to provide health

science students with a variety of co-curricular activities,

including exposure to successfulpractitioners who serve

rural and medically underserved populations. A SPARX

steering committee composed of staff and faculty from

the health science schools created the infrastructure to

link the schools around the program and,in 1996,the

WWAMI Area Health Education Center Program Office

assumed responsibility for administering and funding the

SPARX program.

Staff and students collaboratively develop topics and

projects.Studentparticipantsare continually engaged

and asked to suggest new topics and direction for SPARX

to ensure thatprogram offerings resonate with student

interests, which shift over time in response to social and

political eventslike health reform efforts,emerging

research,and pop culture. SPARX reaches out to

studentsthrough a variety ofmeans,including flyers,

advertisements,and social media such as Facebook.

Experiencehas demonstrated,however,that nothing

substitutesfor the effective outreach realized through

student meetings and class orientations.

The SPARX program consists of three elements:

forums and seminars on topics ofinterest or value for

rural and urban underserved providersto stimulate

studentinterest,training to develop skillsand foster

interprofessionalrelationships among students,and ser-

vice projects to provide experientiallearning and foster

collaborative teamwork acrossinvolved health profes-

sions students.Early SPARX projects focused on health

and wellnessin rural children,kids’ health screening,

clothing drives, and outreach to migrant farm workers in

the fields.In the late 1990s SPARX supported a mobile

outreach and primary care projectfor urban homeless

and street-involved youth.More recently,SPARX has

partnered with Seattle Head Startto provide sensory

assessments for children in its programs and larger urban

health fairs targeting medically underserved Latinos.

In 1997 SPARX created the SPARX Participation

Award to allow studentsto earn a certificate through

attendance at seminars and support for projects. Students

who gain the certificate are named in a letter to their

respective deans and faculty advisors.In 2007 SPARX

and a sister program in the Departmentof Family

Medicine, the Community Health Advancement Program

(CHAP), linked through a shared rolein delivering

program seminars,combinedthe award. This link

allowed students participating in either program to earn

points towards the shared SPARX/CHAP Award, recog-

nizing thatstudentshad increasingly limited time for

Table 4. University of Washington IPE competencies

Respects the roles and approaches to clinicaland social

problems of one’s own and other disciplines

Consults with others when outside his/her personalor profes-

sionalexpertise

Collaborates effectively with others to assess, plan, provide, and

review care that optimizes health outcomes for patients

Collaborates effectively with other health professionals in a

variety of venues and practice settings

Raises issues or concerns that may jeopardize patient outcomes

with other team members

Demonstrates consensus building and appropriate negotiation/

conflict management skills in resolving issues and concerns

Fulfills roles as either a designated or situationalteam leader

Assists in identifying and overcoming barriers to interprofessional

collaboration

Diane R. Bridges et al.

6(page number not for citation purpose)

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

service activities and shouldn’thave to choose between

program offerings on account of the certificate.

Demand for and participation in the SPARX program

has increased over time.In 19951996 fewer than 100

students participated, and of those more than 70 per cent

were medicalstudents.In 20092010 more than 500

students from allthe health sciences participated in at

least one SPARX activity and 87 students will receive the

SPARX/CHAP Award. The Latina Health Fair activity

drew over 140 studentvolunteers,a record for any

University ofWashington-sponsored service projectex-

cept the institutional support for the Martin Luther King

Jr Day of Service.In 20092010 SPARX offered 13

seminars,panels,and forums and seven service projects,

including sensory screening atHead Start, breakfast

programs at a youth homeless shelter nine days a month,

Martin Luther King Jr Day of Service projects, the One

Night Count of Homeless,the Latina Health Fair,and

mentoring at a school for homeless children. The Latina

Health Fair alone reached over 500 families with health

screenings,education,counseling,and referralto the

community health clinic for follow-up, demonstrating the

ability of these programs to reach far into communities.

Common elements among interprofessional

curriculum models

There are many elements ofcollaborative practice that

find their way into successfulIPE experiences like those

described in this paper. These elements include responsi-

bility,accountability,coordination,communication,co-

operation, assertiveness, autonomy, and mutual trust and

respect (6). A successful interprofessional curriculum will

ensure that students can experience,share,and practice

these traits with each other.

Understanding others’professions and your own role

in the healthcareteam is critical in IPE (28). This

represents a longitudinal developmental goal; as students

become more immersed in their own education they are

likely to gain a better and more comprehensive under-

standing of their role in the healthcare team. Though at

first students may not understand the complexities of the

relationships between their profession and others,it is

importantto develop a common framework early in

their education thatdescribes a bestpractice modelof

interprofessional interaction. This will provide a goal that

they can work towards as they move from studentto

professionalhealthcare team member.As a part of this

enhanced understanding,exploring boundaries ofeach

profession will help students understand better the duties

for his/her profession.

Another key element is for students to ‘see’ the impact

of interprofessionalefforts and reflect on the experience

to help reinforce interprofessional learning outcomes.

For students, their attitudes and perceptions regarding

successfulmodels ofcollaboration,whether clinicalor

educational,can be essentialto the value of the instruc-

tion. Grading studentparticipation willalso add value

for them.

Lastly, the training of mentors/faculty is an important

elementin the successfulinterprofessionalcurriculum.

Mentors and faculty need to feelconfidentin their

interactionswith students.The significanceof any

interprofessionalcourse needs to be shared with faculty

so they can see its importance.

Resources

An interprofessionalcurriculum requiresa significant

commitmentfrom university administration,as wellas

deans and faculty from multiple professions who must

be willing to champion the effort. Each curriculum

effort should be critically evaluated,both quantitatively

and qualitatively.In addition, we have found the

following resources to be crucialto the success ofthe

interprofessionalleaning experience.

For didactic learning experiences,consider the

following.

1. Commitment from departments and colleges to set

aside time for students to participate in the course.

2. Curricular mapping between schools can facilitate

activities.

3. Adequate rooms and facilities able to accommodate

large numbers of students,faculty,staff,and com-

munity members.

4. Creation of a space for a sense of community and

shared purpose through ice-breaking activities and

introductions.

5. Technology for web-based conferences to reach all

participants, as well as a learning system to admin-

ister course content materials and grade students.

For community-based learning experiencesfor stu-

dents, consider the following.

1. Do you have an enthusiasticcommitmentfrom

community partners?

2. Create projects which utilize a diversity ofprofes-

sions.

3. If you are using families or individuals, do you have

clear expectations as to whether this is simply an

educational experience for your students or delivery

of healthcare?

4. Are there contingencies for community participants

who become lost to follow-up?

5. Confidentiality of personal health information must

be a high priority.

6. The university must develop a community presence

so that year after year these relationships can be

strengthened and new partnerships formed.

Models of interprofessionaleducation

Citation: MedicalEducation Online 2011, 16: 6035 -DOI: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 7(page number not for citation purpose)

program offerings on account of the certificate.

Demand for and participation in the SPARX program

has increased over time.In 19951996 fewer than 100

students participated, and of those more than 70 per cent

were medicalstudents.In 20092010 more than 500

students from allthe health sciences participated in at

least one SPARX activity and 87 students will receive the

SPARX/CHAP Award. The Latina Health Fair activity

drew over 140 studentvolunteers,a record for any

University ofWashington-sponsored service projectex-

cept the institutional support for the Martin Luther King

Jr Day of Service.In 20092010 SPARX offered 13

seminars,panels,and forums and seven service projects,

including sensory screening atHead Start, breakfast

programs at a youth homeless shelter nine days a month,