Early Intervention Services for Infants and Toddles at Risk for Developmental Delays

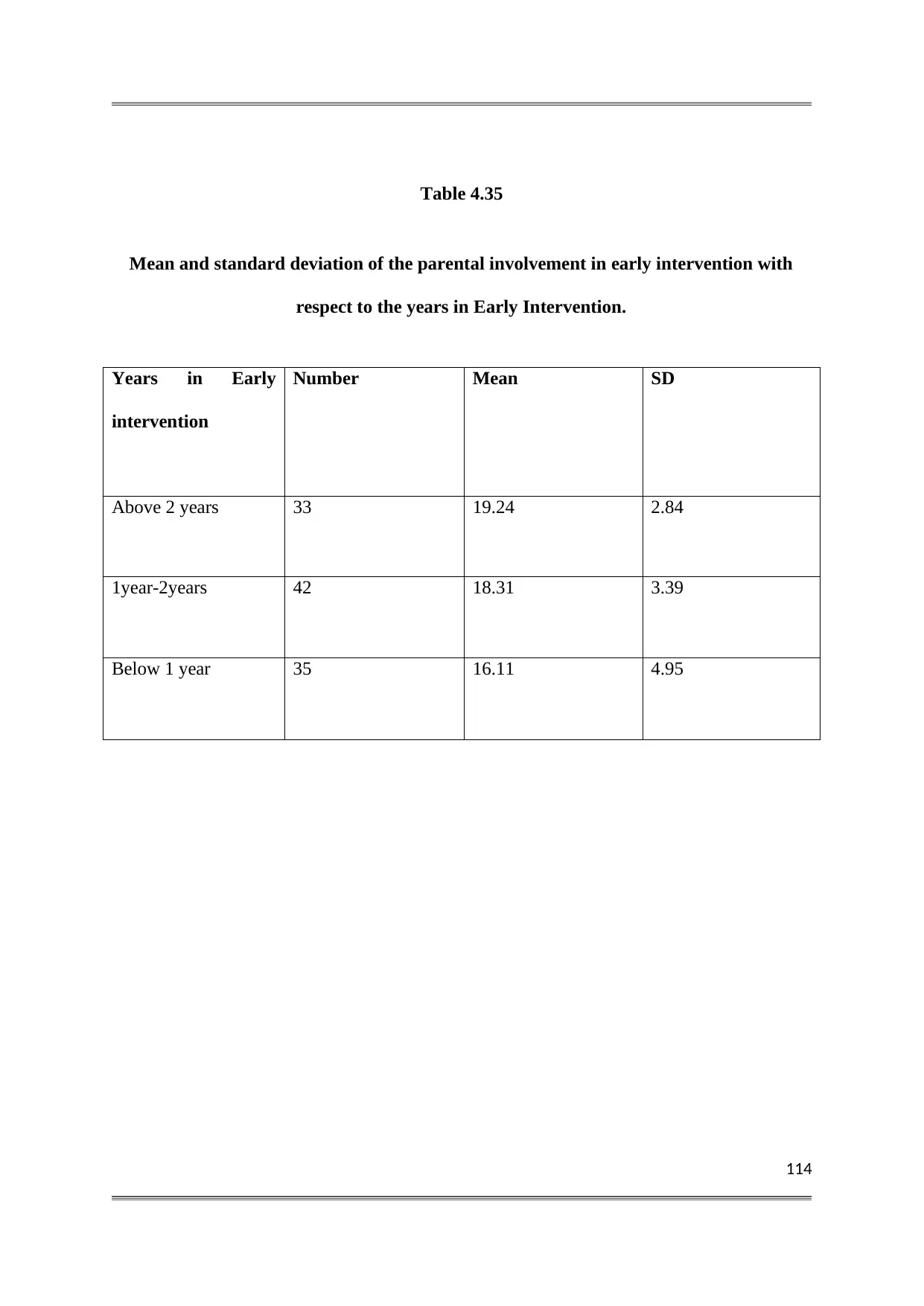

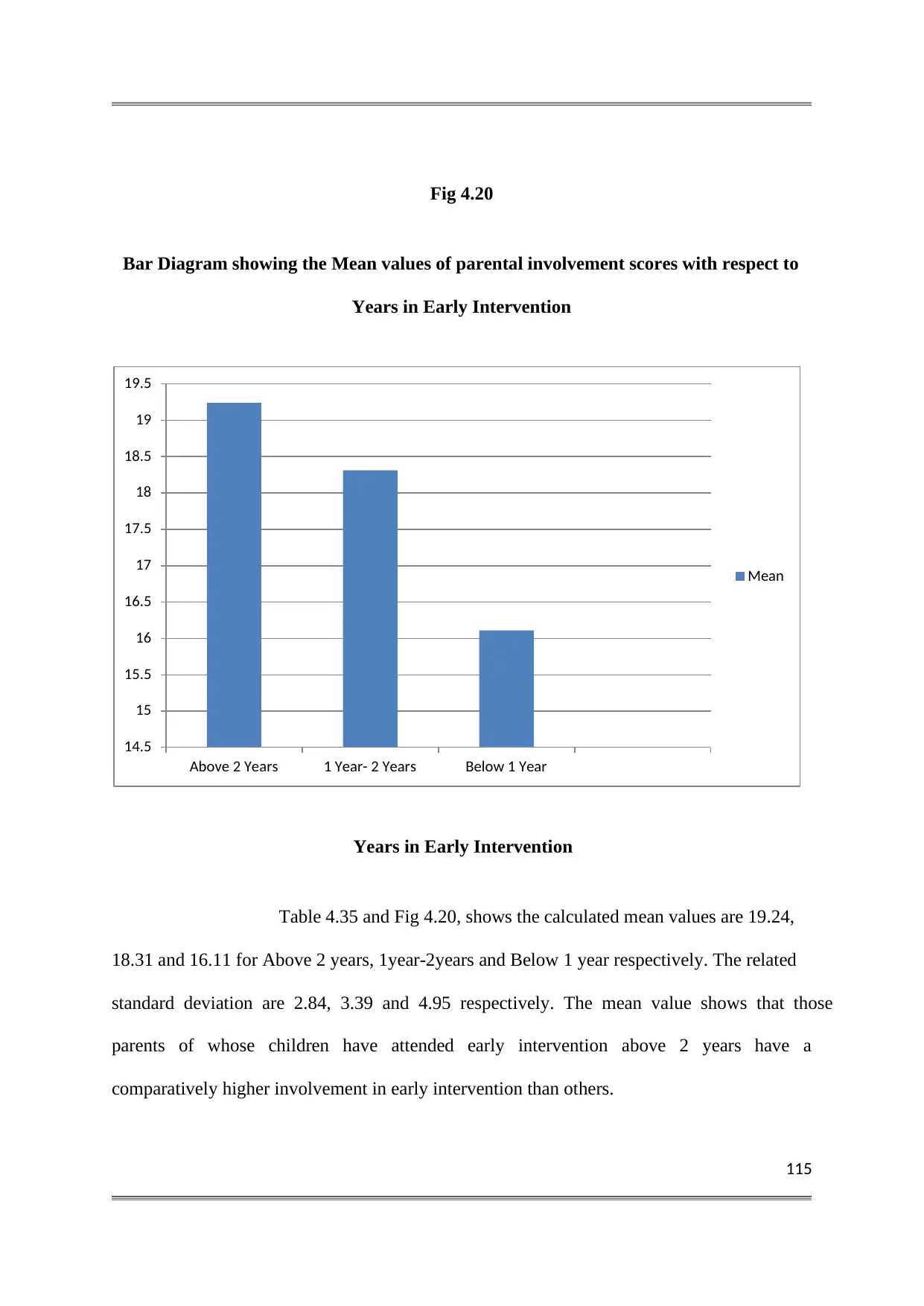

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/22

|135

|23968

|427

AI Summary

Thus the family's increased ability to cope with the presence of an exceptional child, and perhaps the child's increased eligibility for employment provide economic and social benefits (NIMH, 2008, pp. 11-12) In the Early Intervention Program (EIP), the primary prevention level is to reduce the occurrence of developmental disability through reduction of risk factors such as low birth weight, malnutrition and family awareness that child development can be influenced by their efforts.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

Early Intervention Services are special services for infants and toddlers

at risk for developmental delays. These services are designed to identify and meet children’s

needs in five developmental areas. These are physical, cognitive, communication, social or

emotional development, sensory and adaptive development. Early intervention includes

provision of services to such children and their families for the purpose of lessening the

effects of the condition. Early intervention can be remedial or preventive in nature-

remediating the existing developmental problems or preventing their occurrence.

Early Intervention Services are effective ways to address the needs of

infants and toddlers with developmental delays or disabilities. To ascertain the eligibility of

the child for early intervention certain screening and diagnostic measures are adopted. Some

children develop more slowly than the others or develop in ways that seem different from

other children. Any deviation from the normal development should be dealt with at the

earliest as it may lead to a developmental delay or the child may be at risk of developing

developmental delays.

The rate of human learning and development is most rapid in the early

years of life. Timing of intervention becomes particularly important when a child runs the

risk of missing an opportunity to learn during a state of maximum readiness. If the most

teachable moments or stages of greatest readiness are not taken advantage of, a child may

have difficulty in learning a particular skill at a later time. It is possible through early

identification and appropriate intervention that children can be helped to reach their

maximum potential.

INTRODUCTION

1.1 CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

Early Intervention Services are special services for infants and toddlers

at risk for developmental delays. These services are designed to identify and meet children’s

needs in five developmental areas. These are physical, cognitive, communication, social or

emotional development, sensory and adaptive development. Early intervention includes

provision of services to such children and their families for the purpose of lessening the

effects of the condition. Early intervention can be remedial or preventive in nature-

remediating the existing developmental problems or preventing their occurrence.

Early Intervention Services are effective ways to address the needs of

infants and toddlers with developmental delays or disabilities. To ascertain the eligibility of

the child for early intervention certain screening and diagnostic measures are adopted. Some

children develop more slowly than the others or develop in ways that seem different from

other children. Any deviation from the normal development should be dealt with at the

earliest as it may lead to a developmental delay or the child may be at risk of developing

developmental delays.

The rate of human learning and development is most rapid in the early

years of life. Timing of intervention becomes particularly important when a child runs the

risk of missing an opportunity to learn during a state of maximum readiness. If the most

teachable moments or stages of greatest readiness are not taken advantage of, a child may

have difficulty in learning a particular skill at a later time. It is possible through early

identification and appropriate intervention that children can be helped to reach their

maximum potential.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

2

Early intervention services also have a significant impact on the parents and siblings of an

exceptional infant or young child. The family of a young exceptional child often feels

disappointed socially isolated and suffers from added stress, frustration, chronic, sorrow,

anxiety and helplessness. The compounded stress with the presence of an exceptional child

may affect the family’s well being which in turn may interfere with the child’s development.

Early intervention can result in parents having improved attitudes about themselves and their

child, improved information and skills for teaching their child and more time for leisure and

enjoyment.

Intervening early is also beneficial to the society at large as it ensures

the child’s developmental and educational gains which will decrease its dependence upon

social institutions. Thus the family’s increased ability to cope with the presence of an

exceptional child, and perhaps the child’s increased eligibility for employment provide

economic as well as social benefits (NIMH, 2008, pp. 11-12)

In Early Intervention Program (EIP), the primary prevention level is to

reduce the occurrence of developmental disability through reduction of risk factors such as

low birth weight, malnutrition and family awareness that child development can be

influenced by their efforts. At a Secondary Prevention level, the goal is to reduce the extent

of manifested childhood disability and shorten its duration. Infant stimulation and

remediation programs operate at this level. In Tertiary Prevention, the aim is to prevent or

reduce complications of disability (physical and behavioral) that lead to a need for

institutionalization. The Program should also enhance the family’s understanding of its

infant’s limitations, strengths and needs, and promote the family’s ability to advocate for its

Early intervention services also have a significant impact on the parents and siblings of an

exceptional infant or young child. The family of a young exceptional child often feels

disappointed socially isolated and suffers from added stress, frustration, chronic, sorrow,

anxiety and helplessness. The compounded stress with the presence of an exceptional child

may affect the family’s well being which in turn may interfere with the child’s development.

Early intervention can result in parents having improved attitudes about themselves and their

child, improved information and skills for teaching their child and more time for leisure and

enjoyment.

Intervening early is also beneficial to the society at large as it ensures

the child’s developmental and educational gains which will decrease its dependence upon

social institutions. Thus the family’s increased ability to cope with the presence of an

exceptional child, and perhaps the child’s increased eligibility for employment provide

economic as well as social benefits (NIMH, 2008, pp. 11-12)

In Early Intervention Program (EIP), the primary prevention level is to

reduce the occurrence of developmental disability through reduction of risk factors such as

low birth weight, malnutrition and family awareness that child development can be

influenced by their efforts. At a Secondary Prevention level, the goal is to reduce the extent

of manifested childhood disability and shorten its duration. Infant stimulation and

remediation programs operate at this level. In Tertiary Prevention, the aim is to prevent or

reduce complications of disability (physical and behavioral) that lead to a need for

institutionalization. The Program should also enhance the family’s understanding of its

infant’s limitations, strengths and needs, and promote the family’s ability to advocate for its

3

infant. For effective intervention, a multi-disciplinary team approach has been advocated, the

composition of which may vary depending on the available resources.

1.2 NEED AND SIGNIFICANCE OF STUDY

The rationale behind Early Intervention is that much of what the child

learns as an infant or a very young child is important to the development of later

competencies. This implies that early learning is foundation to later learning which is one of

the principles of child development.

This gets ample support from Piaget’s theory of Cognitive

development in which intelligence is depicted as a developmental phenomenon and an

adaptive process. The basic behavior patterns or schemes which are acquired, repeated,

integrated or in combination form complex response patterns which help in achieving higher

cognitive proficiency. He also considered this early age of 0-2 as Sensory-motor period.

Hence the early age period is the most appropriate period to lay the basic foundations for

further development and learning. The early childhood period is considered a critical period

and early intervention programmes utilize these periods to the best advantage of the child.

(NIMH, 2008, p.13)

Early Intervention Services include a range of healthcare,

developmental, therapeutic, social and cultural services for young children and their families.

Children grow very rapidly in early years and any stimulation at this stage helps to promote a

child’s optimum growth and development.

Thus it is presumed that early intervention provides the brain a second

chance to revisit some of the developmental stages which have once been omitted or

incomplete.

infant. For effective intervention, a multi-disciplinary team approach has been advocated, the

composition of which may vary depending on the available resources.

1.2 NEED AND SIGNIFICANCE OF STUDY

The rationale behind Early Intervention is that much of what the child

learns as an infant or a very young child is important to the development of later

competencies. This implies that early learning is foundation to later learning which is one of

the principles of child development.

This gets ample support from Piaget’s theory of Cognitive

development in which intelligence is depicted as a developmental phenomenon and an

adaptive process. The basic behavior patterns or schemes which are acquired, repeated,

integrated or in combination form complex response patterns which help in achieving higher

cognitive proficiency. He also considered this early age of 0-2 as Sensory-motor period.

Hence the early age period is the most appropriate period to lay the basic foundations for

further development and learning. The early childhood period is considered a critical period

and early intervention programmes utilize these periods to the best advantage of the child.

(NIMH, 2008, p.13)

Early Intervention Services include a range of healthcare,

developmental, therapeutic, social and cultural services for young children and their families.

Children grow very rapidly in early years and any stimulation at this stage helps to promote a

child’s optimum growth and development.

Thus it is presumed that early intervention provides the brain a second

chance to revisit some of the developmental stages which have once been omitted or

incomplete.

4

Therefore the basis for early intervention is that by providing a

stimulating environment, creating appropriate opportunities for learning and providing

support to the families, young children who are at risk or already have developmental delays

could be helped.

Intervention encourages and helps parents to gain skills in observing

their infants and young children, and in understanding that children learn from their play.

Parents are helped to become aware of materials and activities that are suitable for children at

each stage of development, and the community resources and services are made available to

them as they work with their children.

The child is considered to be “at risk” because of adverse genetic,

prenatal, perinatal, neonatal or environmental influences that may lead to subsequent

development of a handicap or developmental deviation. Intelligence and other human

capacities are not fixed at birth, but rather they are shaped to some extent by environmental

influences and through learning. Handicapping conditions may interfere with development

and learning due to which disability becomes serious and secondary handicaps may appear.

Parents need special assistance in establishing meaningful patterns of parenting a

handicapping conditions or a child at risk. Parental involvement is considered to be a key

element in the success of early intervention programs. Parental involvement is necessary in

providing adequate care, stimulation and training for their child during critical years when

basic developmental skills should be established.

Many reasons have been offered for why parents should be involved in

early intervention programs. (Bristol & Gallagher, 1982; Peterson, 1987; Turnbull &

Turnbull, 1986)

Therefore the basis for early intervention is that by providing a

stimulating environment, creating appropriate opportunities for learning and providing

support to the families, young children who are at risk or already have developmental delays

could be helped.

Intervention encourages and helps parents to gain skills in observing

their infants and young children, and in understanding that children learn from their play.

Parents are helped to become aware of materials and activities that are suitable for children at

each stage of development, and the community resources and services are made available to

them as they work with their children.

The child is considered to be “at risk” because of adverse genetic,

prenatal, perinatal, neonatal or environmental influences that may lead to subsequent

development of a handicap or developmental deviation. Intelligence and other human

capacities are not fixed at birth, but rather they are shaped to some extent by environmental

influences and through learning. Handicapping conditions may interfere with development

and learning due to which disability becomes serious and secondary handicaps may appear.

Parents need special assistance in establishing meaningful patterns of parenting a

handicapping conditions or a child at risk. Parental involvement is considered to be a key

element in the success of early intervention programs. Parental involvement is necessary in

providing adequate care, stimulation and training for their child during critical years when

basic developmental skills should be established.

Many reasons have been offered for why parents should be involved in

early intervention programs. (Bristol & Gallagher, 1982; Peterson, 1987; Turnbull &

Turnbull, 1986)

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

5

The following rationales are frequently offered as to why it is

important to involve parents:

Parents are responsible for the welfare of their children. Most parents want a voice in how

their child is educated because they are ultimately responsible for the child's well-being

and welfare.

Early intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children.

It is often alleged that, by involving the family (i.e., the people with whom the child

spends the majority of his or her time), the benefits of early intervention programs will be

strengthened.

Parent involvement activities benefit parents and family members. By helping parents

understand their child's current situation and potential and how to manage their child's

needs and demands, it is often claimed that parents will have reduced levels of stress,

more satisfaction, and a more realistic perception of what is possible and desirable.

Participation in early intervention programs also exposes parents to other agencies and

services which may be useful to them in other aspects of their life.

By involving parents, the same outcomes can be achieved at less cost. Early intervention

services can be very expensive. If parents can be used to deliver a portion of the services,

it is often suggested that the costs of early intervention can be dramatically reduced.

The benefits of early intervention are maintained better if parents are involved. It is often

argued that the involvement of parents will reinforce and maintain the benefits of early

intervention because they are the only ones who will be consistently involved with the

The following rationales are frequently offered as to why it is

important to involve parents:

Parents are responsible for the welfare of their children. Most parents want a voice in how

their child is educated because they are ultimately responsible for the child's well-being

and welfare.

Early intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children.

It is often alleged that, by involving the family (i.e., the people with whom the child

spends the majority of his or her time), the benefits of early intervention programs will be

strengthened.

Parent involvement activities benefit parents and family members. By helping parents

understand their child's current situation and potential and how to manage their child's

needs and demands, it is often claimed that parents will have reduced levels of stress,

more satisfaction, and a more realistic perception of what is possible and desirable.

Participation in early intervention programs also exposes parents to other agencies and

services which may be useful to them in other aspects of their life.

By involving parents, the same outcomes can be achieved at less cost. Early intervention

services can be very expensive. If parents can be used to deliver a portion of the services,

it is often suggested that the costs of early intervention can be dramatically reduced.

The benefits of early intervention are maintained better if parents are involved. It is often

argued that the involvement of parents will reinforce and maintain the benefits of early

intervention because they are the only ones who will be consistently involved with the

6

child. Responsibilities of agencies may change, the family may move, funding may be

cut, but the child will always be a member of his/her family.

Hence, it is important, that parents of children with developmental

disabilities be aware and be fully involved in early intervention services. In this context, there

is a need to study about the awareness and involvement of parents in early intervention, its

services and benefits for their children suffering from developmental disabilities.

1.3 SCOPE OF THE STUDY

This study is expected to throw light on the need for parental

awareness and involvement in early intervention. The advantage of examining the parental

awareness and involvement on different aspects of early intervention are that they can

increase the knowledge base regarding parental awareness and involvement. Another

advantage of the study is that, recommendations can be made to early intervention centers

and families on the need to be aware and involved in various aspects of early intervention for

the benefit of disabled children. It is hoped that, the findings of the study will help the

administrators and therapists of early intervention centers to create awareness among the

parents on the importance of parental involvement in early intervention. The investigator

expects the results of the study would be of use to all, concerned with the education, training

and development of children with developmental disabilities.

1.4 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The study aims in ascertaining the level of awareness and involvement

of parents on early Intervention of children with developmental disabilities. Therefore, the

study is entitled as “Awareness and Involvement of Parents in Early Intervention of

Children with Developmental disabilities”

child. Responsibilities of agencies may change, the family may move, funding may be

cut, but the child will always be a member of his/her family.

Hence, it is important, that parents of children with developmental

disabilities be aware and be fully involved in early intervention services. In this context, there

is a need to study about the awareness and involvement of parents in early intervention, its

services and benefits for their children suffering from developmental disabilities.

1.3 SCOPE OF THE STUDY

This study is expected to throw light on the need for parental

awareness and involvement in early intervention. The advantage of examining the parental

awareness and involvement on different aspects of early intervention are that they can

increase the knowledge base regarding parental awareness and involvement. Another

advantage of the study is that, recommendations can be made to early intervention centers

and families on the need to be aware and involved in various aspects of early intervention for

the benefit of disabled children. It is hoped that, the findings of the study will help the

administrators and therapists of early intervention centers to create awareness among the

parents on the importance of parental involvement in early intervention. The investigator

expects the results of the study would be of use to all, concerned with the education, training

and development of children with developmental disabilities.

1.4 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The study aims in ascertaining the level of awareness and involvement

of parents on early Intervention of children with developmental disabilities. Therefore, the

study is entitled as “Awareness and Involvement of Parents in Early Intervention of

Children with Developmental disabilities”

7

1.5 OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS

Definitions of the important terms used in this study are given below:-

AWARENESS

Knowledge or perception of a situation or fact.

INVOLVEMENT

To cause someone to be associated with someone or something.

In this study, ‘Parental involvement’ means the active role of parents in their child’s early

intervention program.

PARENTS

Father or Mother of children with developmental disabilities.

EARLY INTERVENTION

Early Intervention is a term, which broadly refers to a wide range of experiences and supports

provided to children, parents and families during the pregnancy, infancy and early childhood

period of development.

CHILDREN WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

Developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to impairment in physical, learning,

language or behavior areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may

impact day to day functioning and usually last through a person’s life.

1.5 OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS

Definitions of the important terms used in this study are given below:-

AWARENESS

Knowledge or perception of a situation or fact.

INVOLVEMENT

To cause someone to be associated with someone or something.

In this study, ‘Parental involvement’ means the active role of parents in their child’s early

intervention program.

PARENTS

Father or Mother of children with developmental disabilities.

EARLY INTERVENTION

Early Intervention is a term, which broadly refers to a wide range of experiences and supports

provided to children, parents and families during the pregnancy, infancy and early childhood

period of development.

CHILDREN WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

Developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to impairment in physical, learning,

language or behavior areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may

impact day to day functioning and usually last through a person’s life.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

1.6 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

General Objective

To find out the level of awareness and involvement of parents in Early Intervention of

children with developmental disabilities.

Specific Objectives

1. To find out the level of awareness of parents on the importance of Early Intervention.

2. To find out the level of awareness of parents on the importance of parental involvement

in Early Intervention.

3. To find out the level of awareness of parents on developmental disabilities.

4. To find out the level of awareness of parents regarding the Early Intervention services.

5. To find out the level of awareness of parents on Early Intervention with respect to Socio

Demographic Variables.

6. To find out the level of involvement of parents in their child’s Early Intervention

Program.

7. To find out the level of involvement of parents with respect to certain socio-demographic

variables.

1.7 HYPOTHESIS

On the basis of the objectives of the study the researcher developed the following

hypothesis.

There is no significant difference in the level of awareness of parents on early

intervention with respect to selected Socio-demographic variables.

1.6 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

General Objective

To find out the level of awareness and involvement of parents in Early Intervention of

children with developmental disabilities.

Specific Objectives

1. To find out the level of awareness of parents on the importance of Early Intervention.

2. To find out the level of awareness of parents on the importance of parental involvement

in Early Intervention.

3. To find out the level of awareness of parents on developmental disabilities.

4. To find out the level of awareness of parents regarding the Early Intervention services.

5. To find out the level of awareness of parents on Early Intervention with respect to Socio

Demographic Variables.

6. To find out the level of involvement of parents in their child’s Early Intervention

Program.

7. To find out the level of involvement of parents with respect to certain socio-demographic

variables.

1.7 HYPOTHESIS

On the basis of the objectives of the study the researcher developed the following

hypothesis.

There is no significant difference in the level of awareness of parents on early

intervention with respect to selected Socio-demographic variables.

9

There is no significant difference in the level of involvement of parents in early

intervention with respect to selected Socio demographic variables.

1.8 METHODOLOGY IN BRIEF

Methodology implies to the methods the researcher intend to use to collect data. It is the

systematic theoretical analysis of the methods applied to a field of study.

Research Design

The present study attempts to reveal the awareness and involvement of parents in early

intervention of children with developmental disabilities. Descriptive Survey Design is chosen

for the present study.

Population

The study is conducted on a sample of parents of 110 children with developmental disabilities

receiving early intervention from various early intervention centres in Kottayam and

Ernakulam districts.

Sampling Method

Random Sampling technique will be used to select the sample. The study will be conducted

on a sample of parents of 110 children with developmental disabilities.

Tools

The tools for data collection are

Demographic data sheet

Awareness Inventory prepared by the researcher.

Parent Involvement Scale prepared by the researcher.

There is no significant difference in the level of involvement of parents in early

intervention with respect to selected Socio demographic variables.

1.8 METHODOLOGY IN BRIEF

Methodology implies to the methods the researcher intend to use to collect data. It is the

systematic theoretical analysis of the methods applied to a field of study.

Research Design

The present study attempts to reveal the awareness and involvement of parents in early

intervention of children with developmental disabilities. Descriptive Survey Design is chosen

for the present study.

Population

The study is conducted on a sample of parents of 110 children with developmental disabilities

receiving early intervention from various early intervention centres in Kottayam and

Ernakulam districts.

Sampling Method

Random Sampling technique will be used to select the sample. The study will be conducted

on a sample of parents of 110 children with developmental disabilities.

Tools

The tools for data collection are

Demographic data sheet

Awareness Inventory prepared by the researcher.

Parent Involvement Scale prepared by the researcher.

10

Data Collection Procedure

All the tools are developed by the investigator and administered on the sample. The

investigator personally contacted the authorities of Early Intervention Centres. The scope of

the study was briefly explained to them and their permission was sought before collecting

data from parents. Permission of parents was also sought either directly or indirectly through

the authorities. The inventories were distributed and the guidelines and instruction on filling

the inventory were given to the parents by the investigator. The parents filled in the general

data sheet, Parental Awareness Inventory and Parental Involvement Inventory. The collected

data were analyzed with respect to a number of background variables. The following

statistical techniques were used for this purpose:

1) Computation of frequencies and percentages

2) Computation of arithmetic Mean, Median, Mode, Standard Deviation, Skewness and

Kurtosis.

3) Computation of‘t’ value to test the significance of difference between the means of two

groups of data.

4) One Way Analysis of Variance to test the significance of difference between the means of

three or more groups of data

1.9 DELIMITATION

The study is delimited to

Parents of children with developmental disabilities receiving early intervention services

from centres of Kottayam and Ernakulam district.

Data Collection Procedure

All the tools are developed by the investigator and administered on the sample. The

investigator personally contacted the authorities of Early Intervention Centres. The scope of

the study was briefly explained to them and their permission was sought before collecting

data from parents. Permission of parents was also sought either directly or indirectly through

the authorities. The inventories were distributed and the guidelines and instruction on filling

the inventory were given to the parents by the investigator. The parents filled in the general

data sheet, Parental Awareness Inventory and Parental Involvement Inventory. The collected

data were analyzed with respect to a number of background variables. The following

statistical techniques were used for this purpose:

1) Computation of frequencies and percentages

2) Computation of arithmetic Mean, Median, Mode, Standard Deviation, Skewness and

Kurtosis.

3) Computation of‘t’ value to test the significance of difference between the means of two

groups of data.

4) One Way Analysis of Variance to test the significance of difference between the means of

three or more groups of data

1.9 DELIMITATION

The study is delimited to

Parents of children with developmental disabilities receiving early intervention services

from centres of Kottayam and Ernakulam district.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

11

Sample: The size of the sample studied was only 110 and it was taken from only 2

districts of Kerala. A larger sample selected from various other districts could have given

scope for wider generalization to the findings. Moreover, the population being scattered,

did not permit the investigator to increase the sample size.

Time: The present study has been conducted within a limited period of time

Sample: The size of the sample studied was only 110 and it was taken from only 2

districts of Kerala. A larger sample selected from various other districts could have given

scope for wider generalization to the findings. Moreover, the population being scattered,

did not permit the investigator to increase the sample size.

Time: The present study has been conducted within a limited period of time

12

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Literature in Research Methodology refers to the knowledge of a

particular area of investigation of any discipline which includes both theory and practice.

Review means to organize the knowledge of the specific area of research to evolve an edifice

of knowledge, to show that our study would be an addition to that particular field. The task of

review of literature is highly creative and tedious, as the researcher has to synthesize the

available knowledge of the field in a unique way to provide the rationale for his study.

A thorough sophisticated literature review is the foundation and

inspiration for substantial, useful research. Literature review is the written systematic

summary of the research which is conducted on a particular topic. Review of literature is

important any other component of the research process.

When every piece of the ongoing research is connected with the work

already done, it attains an overall relevance and purpose. Review of literature thus becomes a

link between the research proposed and the study already conducted. It conveys to the reader

about those aspects that have already been established or conclude by other authors, and also

give a chance to the reader to appreciate the evidence that has already been collected by

previous research and thus presents the current research work in the right perspective.

A review of literature highlights the differences in opinion,

contradictory findings or evidence and the various explanations given for the conclusions and

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Literature in Research Methodology refers to the knowledge of a

particular area of investigation of any discipline which includes both theory and practice.

Review means to organize the knowledge of the specific area of research to evolve an edifice

of knowledge, to show that our study would be an addition to that particular field. The task of

review of literature is highly creative and tedious, as the researcher has to synthesize the

available knowledge of the field in a unique way to provide the rationale for his study.

A thorough sophisticated literature review is the foundation and

inspiration for substantial, useful research. Literature review is the written systematic

summary of the research which is conducted on a particular topic. Review of literature is

important any other component of the research process.

When every piece of the ongoing research is connected with the work

already done, it attains an overall relevance and purpose. Review of literature thus becomes a

link between the research proposed and the study already conducted. It conveys to the reader

about those aspects that have already been established or conclude by other authors, and also

give a chance to the reader to appreciate the evidence that has already been collected by

previous research and thus presents the current research work in the right perspective.

A review of literature highlights the differences in opinion,

contradictory findings or evidence and the various explanations given for the conclusions and

13

differences by various authors. Such analysis can lead to new possibility that can be

researched upon in the current study. Thus review of literature is an inevitable part of a

Research.

2.2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Early Intervention is defined by Stephens and Tauber (2001) in two

parts; early refers to the most critical period of a child’s development between birth and three

years of age. Intervention refers to programme implementation designed to maintain or

enhance the child’s development in natural environments and as a member of a family.

Dunst (2007) proposed a definition of early (childhood) intervention as

the experiences and opportunities afforded to infants and toddlers (and preschoolers) with

disabilities by the children’s parents and other primary caregivers (including service

providers) that are intended to promote the children’s acquisition and use of behavioral

competencies to shape and influence their prosocial interactions with people and objects.

Early childhood intervention by definition is relationship-based as

families work together with the practitioners as equal partners to design a service plan that is

responsive to family priorities and child needs. Parents and caregivers are the experts on the

unique characteristics of the child and invaluable informants on the child’s strengths,

interests, and abilities, as well as the naturally occurring learning opportunities that exist in

the child and family’s life. The contemporary model of early childhood intervention is

family-centered, and these adult-to-adult interactions between caregivers and professionals

differences by various authors. Such analysis can lead to new possibility that can be

researched upon in the current study. Thus review of literature is an inevitable part of a

Research.

2.2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

Early Intervention is defined by Stephens and Tauber (2001) in two

parts; early refers to the most critical period of a child’s development between birth and three

years of age. Intervention refers to programme implementation designed to maintain or

enhance the child’s development in natural environments and as a member of a family.

Dunst (2007) proposed a definition of early (childhood) intervention as

the experiences and opportunities afforded to infants and toddlers (and preschoolers) with

disabilities by the children’s parents and other primary caregivers (including service

providers) that are intended to promote the children’s acquisition and use of behavioral

competencies to shape and influence their prosocial interactions with people and objects.

Early childhood intervention by definition is relationship-based as

families work together with the practitioners as equal partners to design a service plan that is

responsive to family priorities and child needs. Parents and caregivers are the experts on the

unique characteristics of the child and invaluable informants on the child’s strengths,

interests, and abilities, as well as the naturally occurring learning opportunities that exist in

the child and family’s life. The contemporary model of early childhood intervention is

family-centered, and these adult-to-adult interactions between caregivers and professionals

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

14

can significantly influence the family’s well-being, parenting skills, and positive parental

perceptions of their child’s behavior (Dunst, 2007).

Derrington et al., (2003) stated early intervention is a term commonly

used to encompass a system of services delivered to children with, or at risk for,

developmental delays, before their third birthday.

2.2.1 STUDIES RELATED TO IMPORTANCE OF EARLY INTERVENTION

Derrington et al., (2003) conducted a study on the effectiveness of early

intervention services reported that early experiences and stimulation are critical for optimal

brain development, suggesting the considerable capacity of early intervention to affect the

child. The brain develops by an "experience-dependent" process, where experience activates

certain pathways in the brain and not others. The study indicates that early intervention

ameliorates or prevents developmental delays and gives support to families of children with

delays. Reasons given are:

Neurological evidence supports the provision of intervention early in a child’s life

when the brain is creating connections that will later sub serve all behavior and skills.

Research shows that early intervention during the postnatal period, infancy,

toddlerhood, and early childhood is effective for pre-term, Low Birth Weight and

Very Low Birth Weight children; children with Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy,

expressive language delays, and visual and hearing impairments. It enhances short-

term and long-term physical, cognitive, behavioral, social, emotional, and language

can significantly influence the family’s well-being, parenting skills, and positive parental

perceptions of their child’s behavior (Dunst, 2007).

Derrington et al., (2003) stated early intervention is a term commonly

used to encompass a system of services delivered to children with, or at risk for,

developmental delays, before their third birthday.

2.2.1 STUDIES RELATED TO IMPORTANCE OF EARLY INTERVENTION

Derrington et al., (2003) conducted a study on the effectiveness of early

intervention services reported that early experiences and stimulation are critical for optimal

brain development, suggesting the considerable capacity of early intervention to affect the

child. The brain develops by an "experience-dependent" process, where experience activates

certain pathways in the brain and not others. The study indicates that early intervention

ameliorates or prevents developmental delays and gives support to families of children with

delays. Reasons given are:

Neurological evidence supports the provision of intervention early in a child’s life

when the brain is creating connections that will later sub serve all behavior and skills.

Research shows that early intervention during the postnatal period, infancy,

toddlerhood, and early childhood is effective for pre-term, Low Birth Weight and

Very Low Birth Weight children; children with Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy,

expressive language delays, and visual and hearing impairments. It enhances short-

term and long-term physical, cognitive, behavioral, social, emotional, and language

15

development and reduces the incidence of developmental delays for biologically at

risk children.

Effective intervention can be carried out by parents of various backgrounds in the

home as well as by professionals in a centre.

Early intervention assists the family in obtaining adaptive devices to support the

child’s participation in everyday activities.

Early intervention provides different sources of social support to the family, which

reduces the impact of stress on the family and enhances parent-child interaction and

consequently child development.

Experiences early in life are especially crucial in organizing the

brain's basic structures, as they create the neural foundation for all subsequent

development and behavior (Greenough et al., 1987)

Majnemer (1998) conducted a study on benefits of early intervention

for children with developmental disabilities reported that early Intervention are programmes

designed to enhance the developmental competence of participants and to prevent or

minimize developmental delays. Children targeted for early intervention may either include

environmentally or biologically vulnerable children, or those with established developmental

deficits.

The developmental period of a child has critical importance for learning

and it is even more so in case of a disabled child. The earlier the disability is detected, the

easier it is to effectively help the child both medically and educationally. (Joubish, et al.,

2015)

development and reduces the incidence of developmental delays for biologically at

risk children.

Effective intervention can be carried out by parents of various backgrounds in the

home as well as by professionals in a centre.

Early intervention assists the family in obtaining adaptive devices to support the

child’s participation in everyday activities.

Early intervention provides different sources of social support to the family, which

reduces the impact of stress on the family and enhances parent-child interaction and

consequently child development.

Experiences early in life are especially crucial in organizing the

brain's basic structures, as they create the neural foundation for all subsequent

development and behavior (Greenough et al., 1987)

Majnemer (1998) conducted a study on benefits of early intervention

for children with developmental disabilities reported that early Intervention are programmes

designed to enhance the developmental competence of participants and to prevent or

minimize developmental delays. Children targeted for early intervention may either include

environmentally or biologically vulnerable children, or those with established developmental

deficits.

The developmental period of a child has critical importance for learning

and it is even more so in case of a disabled child. The earlier the disability is detected, the

easier it is to effectively help the child both medically and educationally. (Joubish, et al.,

2015)

16

Landesman Ramey and Ramey (1999) studied the effects of early

experience and early intervention and stated that for 4 decades, vigorous efforts have been

based on the premise that early intervention for children of poverty and, more recently, for

children with developmental disabilities can yield significant improvements in cognitive,

academic, and social outcomes. The study briefly summarized the history of those efforts and

presented a conceptual framework to understand the design, research, and policy relevance of

these early interventions. This framework, biosocial developmental contextualism, derives

from social ecology, developmental systems theory, developmental epidemiology, and

developmental neurobiology. Those integrative perspective predicts that fragmented, weak

efforts in early intervention are not likely to succeed, whereas intensive, high-quality,

ecologically pervasive interventions can and do. Relevant evidence was also summarized in 6

principles about efficacy of early intervention. The public policy challenge in early

intervention is to contain costs by more precisely targeting early interventions to those who

most need and benefit from these interventions. The empirical evidence on biobehavioral

effects of early experience and early intervention has direct relevance to federal and state

policy development and resource allocation.

Beena (2016) conducted a study on early Intervention in Children with

Developmental Disabilities reported that Developmental disabilities consist of conditions that

delay or impair the physical, cognitive, and/or psychological development of children. If not

intervened at the earliest, these disabilities will cause significant negative impact on multiple

domains of functioning such as learning, language, self-care and capacity for independent

living.

Landesman Ramey and Ramey (1999) studied the effects of early

experience and early intervention and stated that for 4 decades, vigorous efforts have been

based on the premise that early intervention for children of poverty and, more recently, for

children with developmental disabilities can yield significant improvements in cognitive,

academic, and social outcomes. The study briefly summarized the history of those efforts and

presented a conceptual framework to understand the design, research, and policy relevance of

these early interventions. This framework, biosocial developmental contextualism, derives

from social ecology, developmental systems theory, developmental epidemiology, and

developmental neurobiology. Those integrative perspective predicts that fragmented, weak

efforts in early intervention are not likely to succeed, whereas intensive, high-quality,

ecologically pervasive interventions can and do. Relevant evidence was also summarized in 6

principles about efficacy of early intervention. The public policy challenge in early

intervention is to contain costs by more precisely targeting early interventions to those who

most need and benefit from these interventions. The empirical evidence on biobehavioral

effects of early experience and early intervention has direct relevance to federal and state

policy development and resource allocation.

Beena (2016) conducted a study on early Intervention in Children with

Developmental Disabilities reported that Developmental disabilities consist of conditions that

delay or impair the physical, cognitive, and/or psychological development of children. If not

intervened at the earliest, these disabilities will cause significant negative impact on multiple

domains of functioning such as learning, language, self-care and capacity for independent

living.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

17

Infancy and early childhood are important times in any child’s life. For

children with disabilities, the early years are critical for a number of reasons. First, the earlier

a child is identified as having a developmental delay or disability, the greater the likelihood

the child will benefit from intervention strategies designed to compensate for the child’s

needs (Guralnick, 2005). Second, families benefit from the support given to them through the

intervention process (Dunst, 2007). Third, schools and communities benefit from a decrease

in costs because more children arrive at school ready to learn (Carta & Kong, 2007).

Early intervention services are multidisciplinary services provided to

children with developmental disabilities, delays, or risks during the first few years of life. The

goal of these programs is to promote the health and optimal development of the children as

well as to support adaptive parenting and positive functioning of their families (Meisels &

Shonkoff, 2000).

Positive early experiences are essential prerequisites for later success in

school, the workplace, and the community. Services to young children who have or are at risk

for developmental delays have been shown to positively impact outcomes across

developmental domains, including health, language and communication, cognitive

development and social/emotional development. Families benefit from early intervention by

being able to better meet their children’s special needs from an early age and throughout their

lives. Benefits to society include reducing economic burden through a decreased need for

special education. (Meisels & Shonkoff, 2000)

Infancy and early childhood are important times in any child’s life. For

children with disabilities, the early years are critical for a number of reasons. First, the earlier

a child is identified as having a developmental delay or disability, the greater the likelihood

the child will benefit from intervention strategies designed to compensate for the child’s

needs (Guralnick, 2005). Second, families benefit from the support given to them through the

intervention process (Dunst, 2007). Third, schools and communities benefit from a decrease

in costs because more children arrive at school ready to learn (Carta & Kong, 2007).

Early intervention services are multidisciplinary services provided to

children with developmental disabilities, delays, or risks during the first few years of life. The

goal of these programs is to promote the health and optimal development of the children as

well as to support adaptive parenting and positive functioning of their families (Meisels &

Shonkoff, 2000).

Positive early experiences are essential prerequisites for later success in

school, the workplace, and the community. Services to young children who have or are at risk

for developmental delays have been shown to positively impact outcomes across

developmental domains, including health, language and communication, cognitive

development and social/emotional development. Families benefit from early intervention by

being able to better meet their children’s special needs from an early age and throughout their

lives. Benefits to society include reducing economic burden through a decreased need for

special education. (Meisels & Shonkoff, 2000)

18

Jain et al., (2013) aimed to identify the age at first concern and age at

referral for rehabilitation services in children with developmental disabilities in India. Two

hundred fifty-nine children were included and data were collected from the parents. In

children with developmental disabilities (excluding autism spectrum disorders), median age

at initial concern was 7 months and age at referral for rehabilitation services was 13 months.

In children with autism spectrum disorders, median age at initial concern was 24 months and

age at referral was 42 months. Physician’s recognition of the condition, single child,

institutional delivery and neonatal admission ≥4 days were associated with early referral. The

common reasons cited by the parents for delay in services were reassurance by physicians or

family members and non-referral by the physicians. The study concluded that, routine

screening for developmental problems (including autism) and improving the awareness of

these conditions among physicians and society would lead to early referral.

Wolery and Bredekamp’s work (as cited in Chippett Darryl, 1999)

offers seven outcomes as defensible goals for programs supporting developmentally delayed

children and their families. They suggest that programs should seek:

1. To support families in achieving their own goals,

2. To promote children's engagement, independence, and mastery,

3. To promote children's development in key domains,

4. To build and support children's social competence,

5. To promote children's generalized use of skills,

Jain et al., (2013) aimed to identify the age at first concern and age at

referral for rehabilitation services in children with developmental disabilities in India. Two

hundred fifty-nine children were included and data were collected from the parents. In

children with developmental disabilities (excluding autism spectrum disorders), median age

at initial concern was 7 months and age at referral for rehabilitation services was 13 months.

In children with autism spectrum disorders, median age at initial concern was 24 months and

age at referral was 42 months. Physician’s recognition of the condition, single child,

institutional delivery and neonatal admission ≥4 days were associated with early referral. The

common reasons cited by the parents for delay in services were reassurance by physicians or

family members and non-referral by the physicians. The study concluded that, routine

screening for developmental problems (including autism) and improving the awareness of

these conditions among physicians and society would lead to early referral.

Wolery and Bredekamp’s work (as cited in Chippett Darryl, 1999)

offers seven outcomes as defensible goals for programs supporting developmentally delayed

children and their families. They suggest that programs should seek:

1. To support families in achieving their own goals,

2. To promote children's engagement, independence, and mastery,

3. To promote children's development in key domains,

4. To build and support children's social competence,

5. To promote children's generalized use of skills,

19

6. To provide and prepare children for normalized Life experiences, and

7. To prevent the emergence of future problems or disabilities.

Brusnahan and Klingenberg (2010) conducted study on evidence-based

practice for young children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, on the basis of the

recommendation of National Resource Council and National Professional Development

Center ASD and suggested guidance to professionals in setting educational programmes that

use effective, research-based interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorders

in early childhood special education.

The following are the specific priority areas of need for autism

spectrum disorder programming.

1. Functional spontaneous communication: Functional spontaneous communication should be

the primary focus of early education. For very young children, programming should be based

on the assumption that most children can learn to speak. Effective teaching techniques for

both verbal language and alternative modes of functional communication, drawn from the

empirical and theoretical literature, should be vigorously applied across settings.

2. Social instruction: Social instruction should be delivered throughout the day in various

settings, using specific activities and interventions planned to meet age-appropriate,

individualized social goals (e.g., with very young children, response to maternal imitation;

with preschool children, cooperative activities with peers).

6. To provide and prepare children for normalized Life experiences, and

7. To prevent the emergence of future problems or disabilities.

Brusnahan and Klingenberg (2010) conducted study on evidence-based

practice for young children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, on the basis of the

recommendation of National Resource Council and National Professional Development

Center ASD and suggested guidance to professionals in setting educational programmes that

use effective, research-based interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorders

in early childhood special education.

The following are the specific priority areas of need for autism

spectrum disorder programming.

1. Functional spontaneous communication: Functional spontaneous communication should be

the primary focus of early education. For very young children, programming should be based

on the assumption that most children can learn to speak. Effective teaching techniques for

both verbal language and alternative modes of functional communication, drawn from the

empirical and theoretical literature, should be vigorously applied across settings.

2. Social instruction: Social instruction should be delivered throughout the day in various

settings, using specific activities and interventions planned to meet age-appropriate,

individualized social goals (e.g., with very young children, response to maternal imitation;

with preschool children, cooperative activities with peers).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

20

3. Play skills: The teaching of play skills should focus on play with peers, with additional

instruction in appropriate use of toys and other materials.

4. Cognitive development: Other instruction aimed at goals for cognitive development should

also be carried out in the context in which the skills are expected to be used with

generalization and maintenance in natural contexts as important as the acquisition of new

skills. Because new skills have to be learned before they can be generalized, the

documentation of rates of acquisition is an important first step. Methods of introduction of

new skills may differ from teaching strategies to support generalization and maintenance.

5. Proactive approaches to behavior problems: Intervention strategies that address problem

behaviors should incorporate information about the contexts in which the behaviors occur;

positive, proactive approaches; and the range of techniques that have empirical support (e.g.,

functional assessment, functional communication training, reinforcement of alternative

behaviors).

6. Functional academic skills: Functional academic skills should be taught when appropriate

to the skills and needs of a child.

In addition to goals and priority areas, the recommendations for educational programming

are:

1. Intervention should begin as soon as a child is suspected of having autism spectrum

disorder.

3. Play skills: The teaching of play skills should focus on play with peers, with additional

instruction in appropriate use of toys and other materials.

4. Cognitive development: Other instruction aimed at goals for cognitive development should

also be carried out in the context in which the skills are expected to be used with

generalization and maintenance in natural contexts as important as the acquisition of new

skills. Because new skills have to be learned before they can be generalized, the

documentation of rates of acquisition is an important first step. Methods of introduction of

new skills may differ from teaching strategies to support generalization and maintenance.

5. Proactive approaches to behavior problems: Intervention strategies that address problem

behaviors should incorporate information about the contexts in which the behaviors occur;

positive, proactive approaches; and the range of techniques that have empirical support (e.g.,

functional assessment, functional communication training, reinforcement of alternative

behaviors).

6. Functional academic skills: Functional academic skills should be taught when appropriate

to the skills and needs of a child.

In addition to goals and priority areas, the recommendations for educational programming

are:

1. Intervention should begin as soon as a child is suspected of having autism spectrum

disorder.

21

2. Intervention should include a child’s active engagement in systematically planned,

age and developmentally appropriate activity toward identified objectives. It is

recommended that intervention occur a minimum of a full school day, at least 5 days a

week (25 hours) with year round programming.

3. Intervention should include teaching that is planned and organized around repeated

short intervals. These intervals should be individualized daily and include one to-one

as well as very small group instructions. All intervention should focus on meeting

individualized goals.

4. Intervention should include the inclusion of a family component, including parent

training.

5. Intervention should include mechanisms for ongoing evaluation of program and

child’s progress, with adjustments made accordingly.

6. Intervention should include inclusive opportunities. For example, to the extent that it

leads to the acquisition of a child’s educational goals, specialized instruction should

occur in a setting in which ongoing interactions occur with typically developing

children.

Meisels and Shonkof’s study (as cited in Chippett. Darryl, 1999) found

that, it is especially critical to intervene early in the life of children who are developmentally

delayed if they are to be provided with the tools necessary to develop to their Full potential.

Helping children develop to their fullest potential before entering kindergarten enables them

to meet with greater success in school. The more skills a child has developed before entering

kindergarten, the fewer the demands placed on the system for individual and remedial

supports. While providing educational resources to developmentally delayed preschoolers

2. Intervention should include a child’s active engagement in systematically planned,

age and developmentally appropriate activity toward identified objectives. It is

recommended that intervention occur a minimum of a full school day, at least 5 days a

week (25 hours) with year round programming.

3. Intervention should include teaching that is planned and organized around repeated

short intervals. These intervals should be individualized daily and include one to-one

as well as very small group instructions. All intervention should focus on meeting

individualized goals.

4. Intervention should include the inclusion of a family component, including parent

training.

5. Intervention should include mechanisms for ongoing evaluation of program and

child’s progress, with adjustments made accordingly.

6. Intervention should include inclusive opportunities. For example, to the extent that it

leads to the acquisition of a child’s educational goals, specialized instruction should

occur in a setting in which ongoing interactions occur with typically developing

children.

Meisels and Shonkof’s study (as cited in Chippett. Darryl, 1999) found

that, it is especially critical to intervene early in the life of children who are developmentally

delayed if they are to be provided with the tools necessary to develop to their Full potential.

Helping children develop to their fullest potential before entering kindergarten enables them

to meet with greater success in school. The more skills a child has developed before entering

kindergarten, the fewer the demands placed on the system for individual and remedial

supports. While providing educational resources to developmentally delayed preschoolers

22

and their families can, in the long term, decrease the costs of education such children, it is the

individual benefits to children that must guide the development and implementation of early

childhood education and intervention programs.

2.2.2 RELATED LITERATURE ON IMPORTANCE OF PARENTAL

INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY INTERVENTION

One of the most frequent assertions coming from reviews of early

intervention program effectiveness is that parental involvement contributes directly to

intervention success (Bronfenbrenner, 1974)

Turnbull’s study (as cited in Sukumaran, 2000) points to the need for

parental involvement. It points to the need for providing parents with some understanding of

the nature of their children’s problems and indicates the importance of sharing educational

and treatment methods and goals.

With regard to early intervention programs for children who are

handicapped, disadvantaged, or at risk, most people would agree with McConachie (1986)

that the general parameters of parent involvement include one or more of the following

components: • Teaching parents specific intervention skills to assist them in becoming more

effective change agents with their child. • Providing social and emotional support to family

members. • Exchange of information between parents and professionals. • Participation of

parents as team members in assessment or program planning • Development of appropriate

parent-child relationships. • Assisting parents in accessing community resources.

and their families can, in the long term, decrease the costs of education such children, it is the

individual benefits to children that must guide the development and implementation of early

childhood education and intervention programs.

2.2.2 RELATED LITERATURE ON IMPORTANCE OF PARENTAL

INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY INTERVENTION

One of the most frequent assertions coming from reviews of early

intervention program effectiveness is that parental involvement contributes directly to

intervention success (Bronfenbrenner, 1974)

Turnbull’s study (as cited in Sukumaran, 2000) points to the need for

parental involvement. It points to the need for providing parents with some understanding of

the nature of their children’s problems and indicates the importance of sharing educational

and treatment methods and goals.

With regard to early intervention programs for children who are

handicapped, disadvantaged, or at risk, most people would agree with McConachie (1986)

that the general parameters of parent involvement include one or more of the following

components: • Teaching parents specific intervention skills to assist them in becoming more

effective change agents with their child. • Providing social and emotional support to family

members. • Exchange of information between parents and professionals. • Participation of

parents as team members in assessment or program planning • Development of appropriate

parent-child relationships. • Assisting parents in accessing community resources.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

23

Parent involvement is essential for successful early intervention

programs are found in the 1986 Amendments to the Education of the Handicapped Act

(Public Law 99-457), which established what amounts to mandated early intervention

programs for all children with handicaps. The committee report, which describes Congress'

rationale behind the legislation, stated, The committee received overwhelming testimony

affirming the family as the primary learning environment for children under six years of age

and pointing out the critical need for parents and professionals to function in a collaborative

manner. (Gilkerson et. al., 1987).

White and Moss (1992) analyzed the evidence from previous research

regarding the benefits associated with the involvement of parents in early intervention

programs and concluded the rationale for involving parents in early intervention programs.

Parents have an obligation to be involved because they are ultimately responsible for their

child's welfare. Involved parents provide better political support and advocacy. Early

intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children. Parent

involvement results in benefits for the parents and family members. By involving parents, the

same outcomes can be achieved at less cost. The benefits of early intervention are maintained

better.

Many reasons have been offered for why parents should be involved in

early intervention programs (Bristol & Gallagher, 1982; Peterson, 1987; Turnbull &

Turnbull, 1986)

Parent involvement is essential for successful early intervention

programs are found in the 1986 Amendments to the Education of the Handicapped Act

(Public Law 99-457), which established what amounts to mandated early intervention

programs for all children with handicaps. The committee report, which describes Congress'

rationale behind the legislation, stated, The committee received overwhelming testimony

affirming the family as the primary learning environment for children under six years of age

and pointing out the critical need for parents and professionals to function in a collaborative

manner. (Gilkerson et. al., 1987).

White and Moss (1992) analyzed the evidence from previous research

regarding the benefits associated with the involvement of parents in early intervention

programs and concluded the rationale for involving parents in early intervention programs.

Parents have an obligation to be involved because they are ultimately responsible for their

child's welfare. Involved parents provide better political support and advocacy. Early

intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children. Parent

involvement results in benefits for the parents and family members. By involving parents, the

same outcomes can be achieved at less cost. The benefits of early intervention are maintained

better.

Many reasons have been offered for why parents should be involved in

early intervention programs (Bristol & Gallagher, 1982; Peterson, 1987; Turnbull &

Turnbull, 1986)

24

The following six rationales have been identified that which are

frequently offered as to why it is important to involve parents: • Parents are responsible for

the welfare of their children. Most parents want a voice in how their child is educated

because they are ultimately responsible for the child's well-being and welfare. Some argue

that, even if parents wanted to relinquish that responsibility to schools or government

agencies, they should not be allowed to do so.

• Involved parents provide better political support and advocacy. Some claim that, if parents

have first-hand information about their child's early intervention program, they will be in a

better position to advocate the further growth and support of those programs. This argument

suggests that, even if programs have very good evidence that there are substantial benefits

resulting from participation, it is absolutely essential in times of fiscal restraint to make sure

that a broad constituency understands and supports their continued growth and funding.

• Early intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children. It

is often alleged that, by involving the family (i.e., the people with whom the child spends the

majority of his or her time), the benefits of early intervention programs will be strengthened.

Parent involvement activities benefit parents and family members. By helping parents

understand their child's current situation and potential and how to manage their child's

needs and demands, it is often claimed that parents will have reduced levels of stress,

more satisfaction, and a more realistic perception of what is possible and desirable.

Participation in early intervention programs also exposes parents to other agencies and

services which may be useful to them in other aspects of their life.

The following six rationales have been identified that which are

frequently offered as to why it is important to involve parents: • Parents are responsible for

the welfare of their children. Most parents want a voice in how their child is educated

because they are ultimately responsible for the child's well-being and welfare. Some argue

that, even if parents wanted to relinquish that responsibility to schools or government

agencies, they should not be allowed to do so.

• Involved parents provide better political support and advocacy. Some claim that, if parents

have first-hand information about their child's early intervention program, they will be in a

better position to advocate the further growth and support of those programs. This argument

suggests that, even if programs have very good evidence that there are substantial benefits

resulting from participation, it is absolutely essential in times of fiscal restraint to make sure

that a broad constituency understands and supports their continued growth and funding.

• Early intervention programs which involve parents result in greater benefits for children. It

is often alleged that, by involving the family (i.e., the people with whom the child spends the

majority of his or her time), the benefits of early intervention programs will be strengthened.

Parent involvement activities benefit parents and family members. By helping parents

understand their child's current situation and potential and how to manage their child's

needs and demands, it is often claimed that parents will have reduced levels of stress,

more satisfaction, and a more realistic perception of what is possible and desirable.

Participation in early intervention programs also exposes parents to other agencies and

services which may be useful to them in other aspects of their life.

25

By involving parents, the same outcomes can be achieved at less cost. Early intervention

services can be very expensive. If parents can be used to deliver a portion of the services,

it is often suggested that the costs of early intervention can be dramatically reduced.

The benefits of early intervention are maintained better if parents are involved. It is often

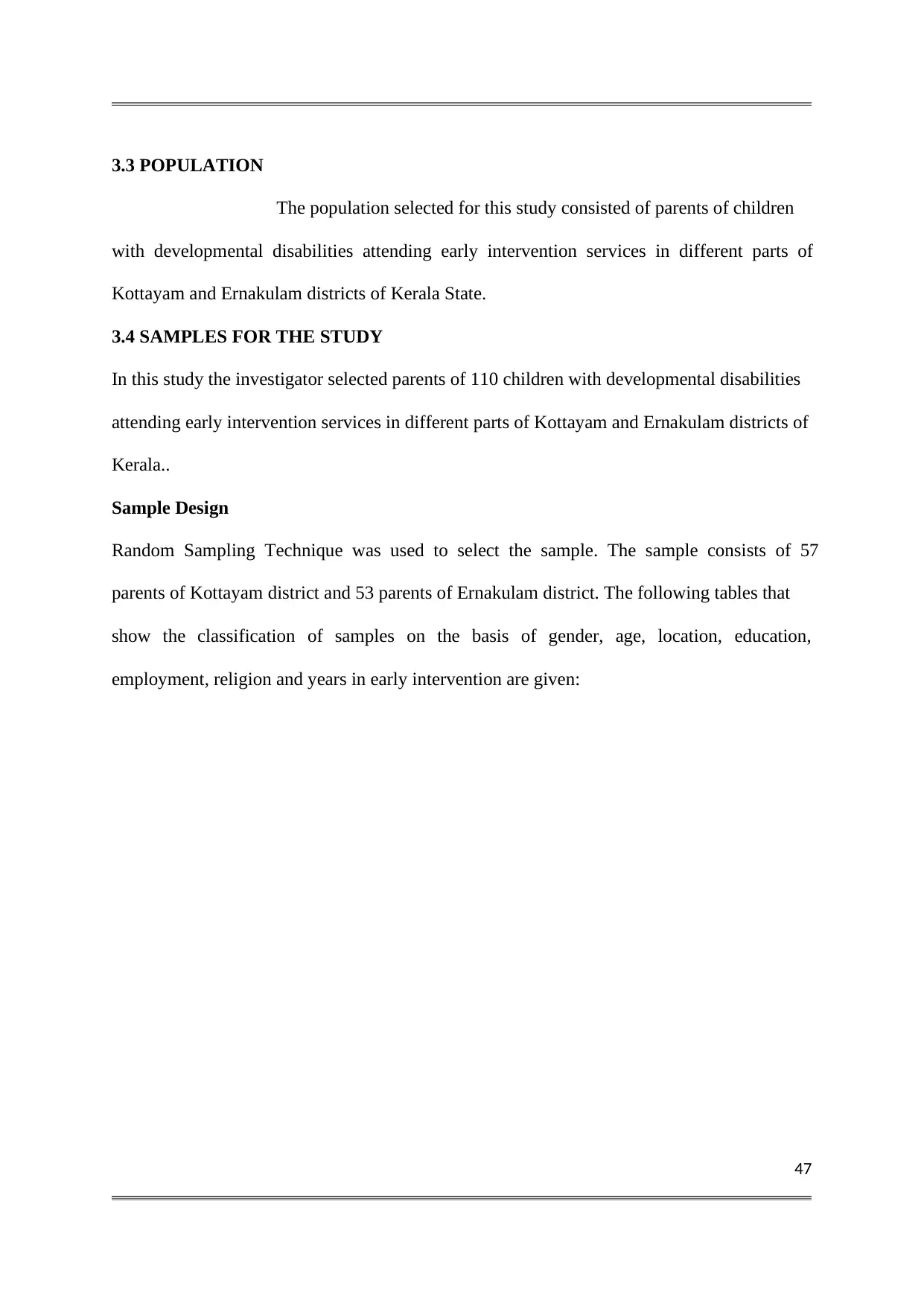

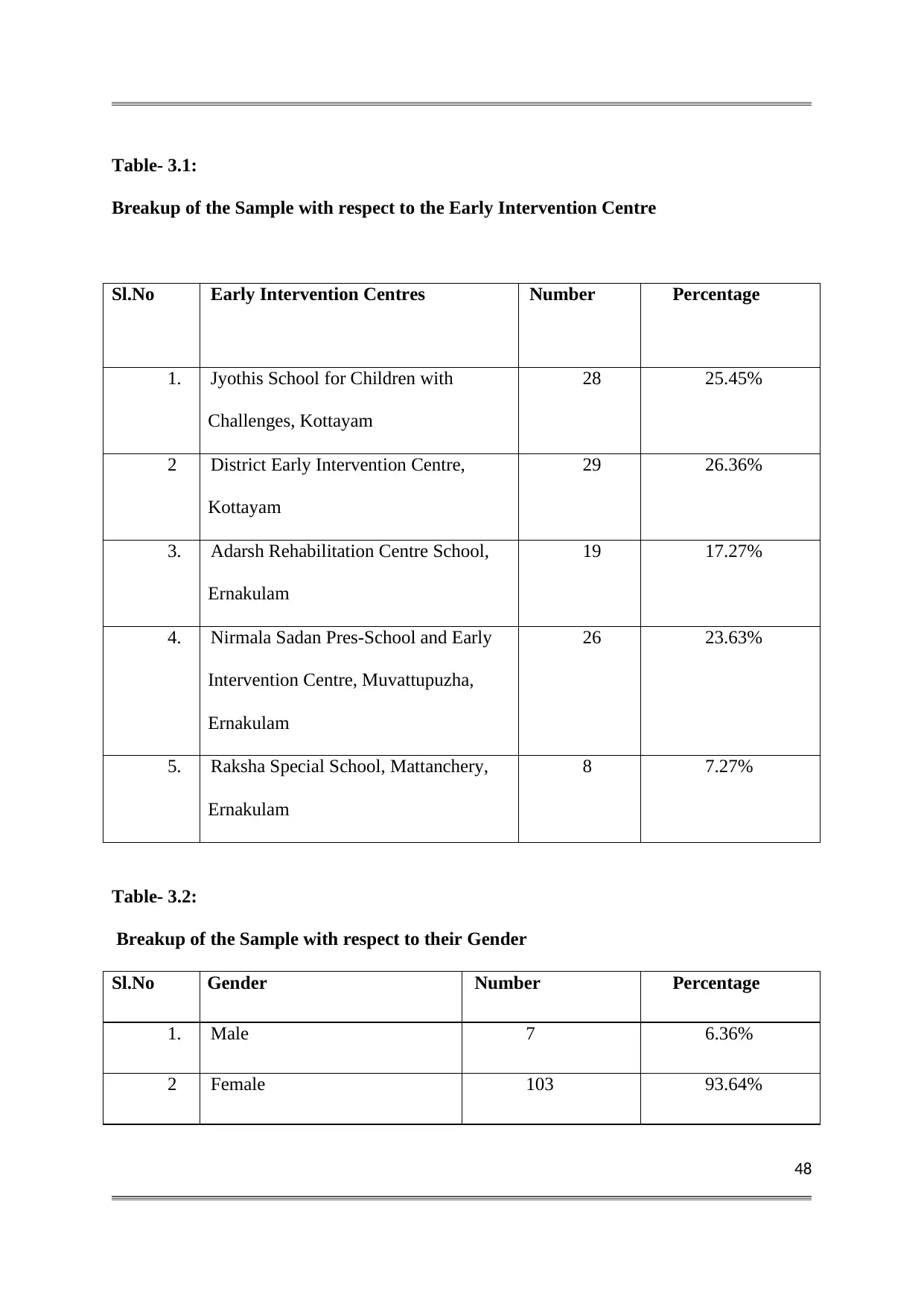

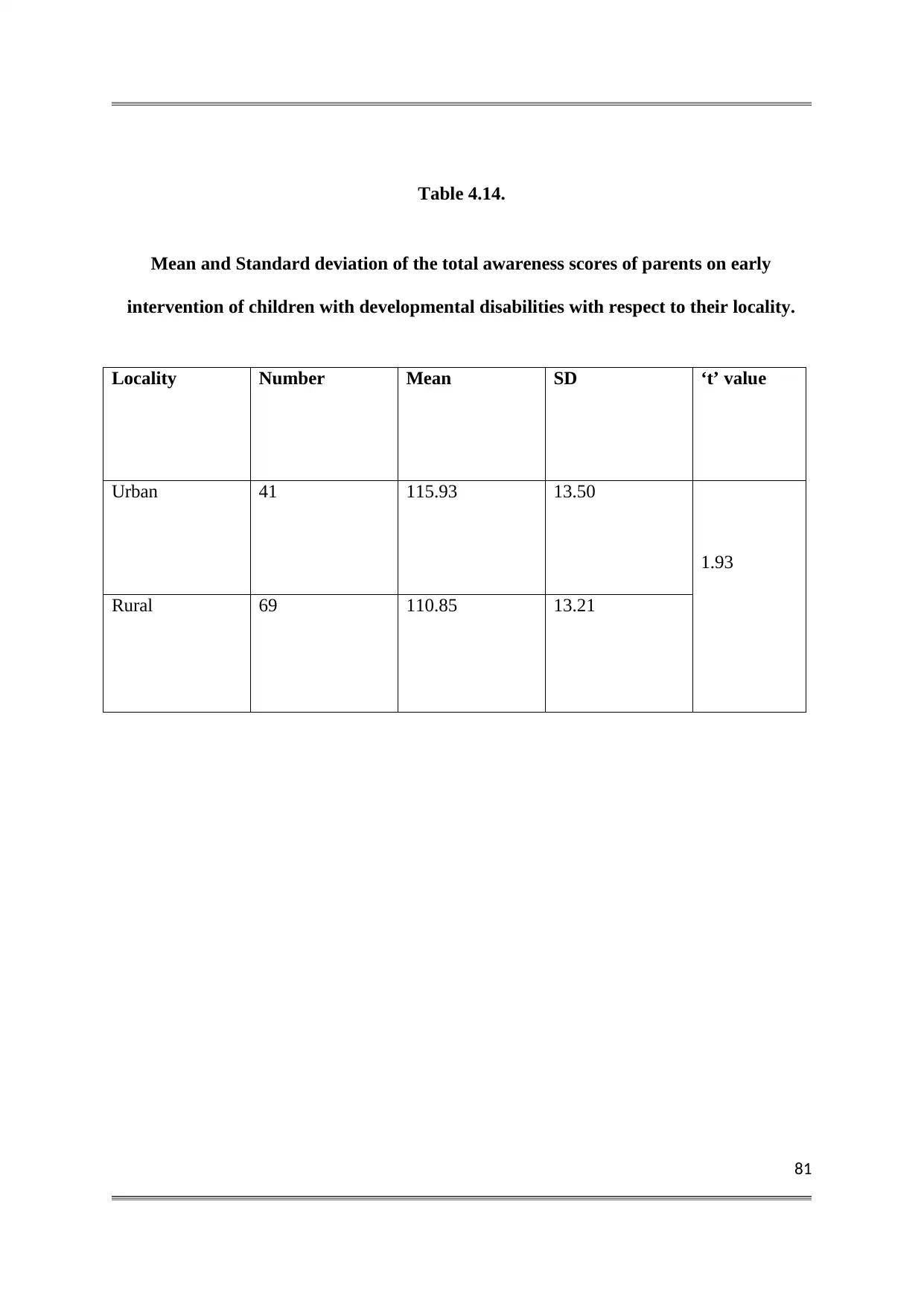

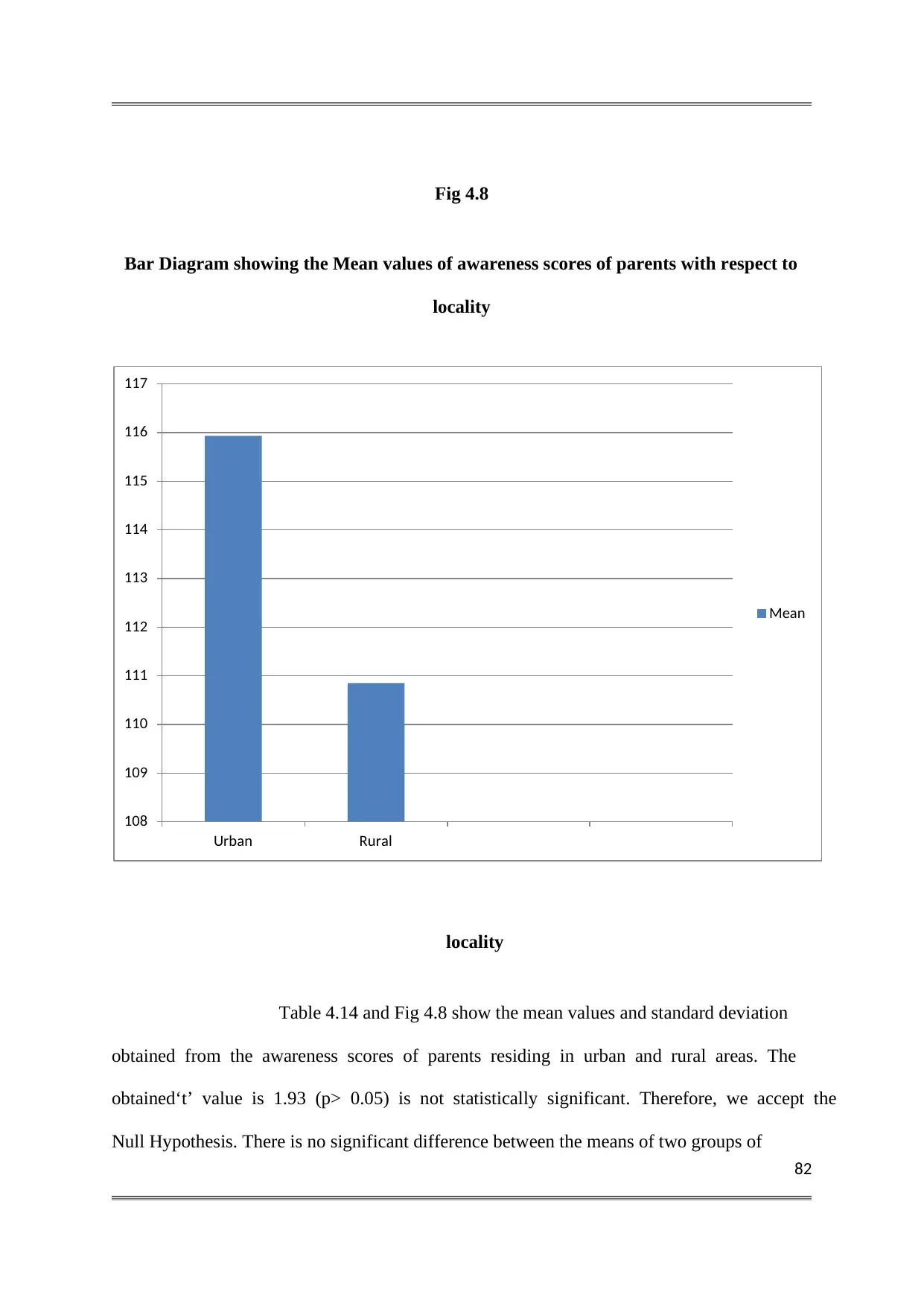

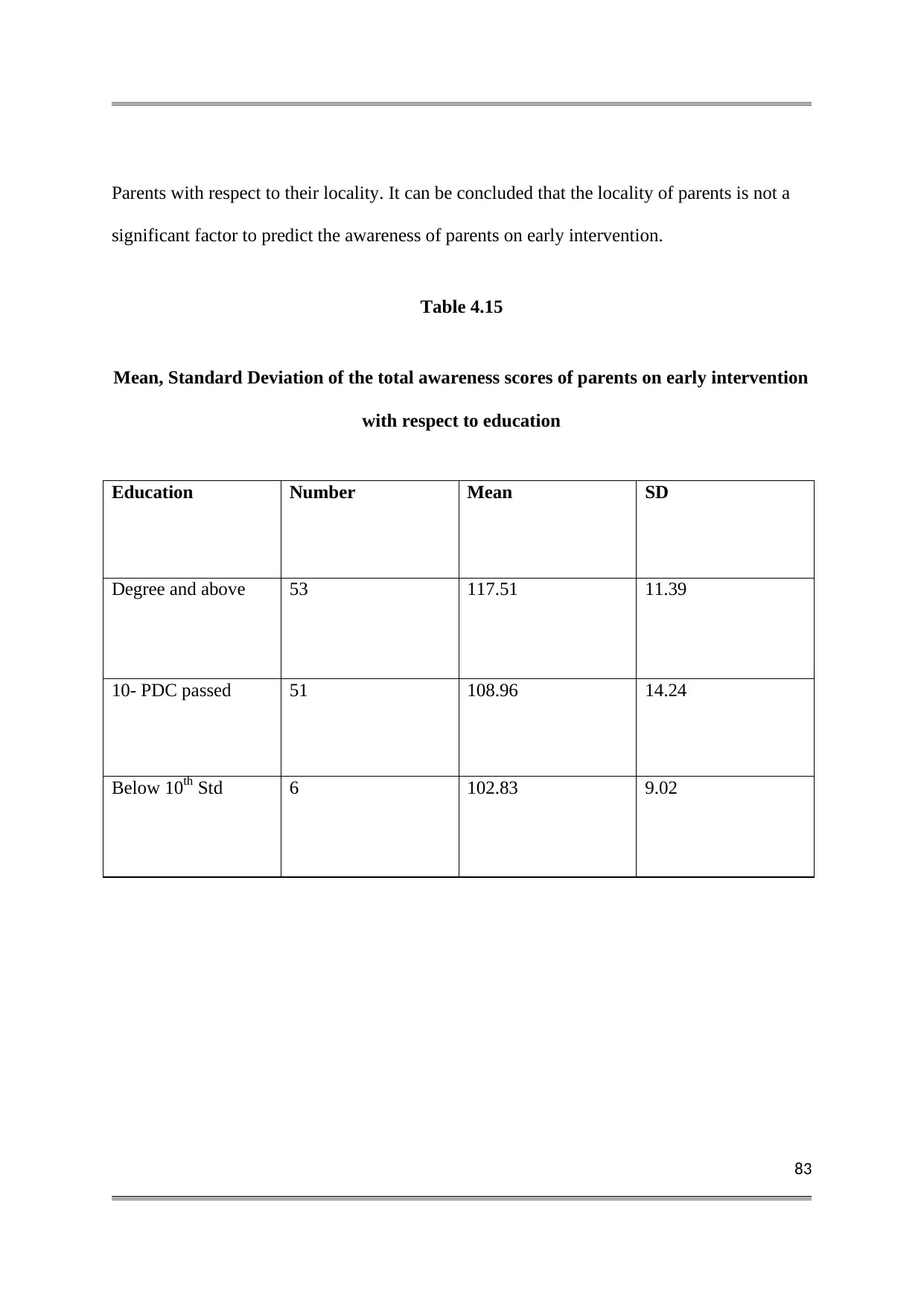

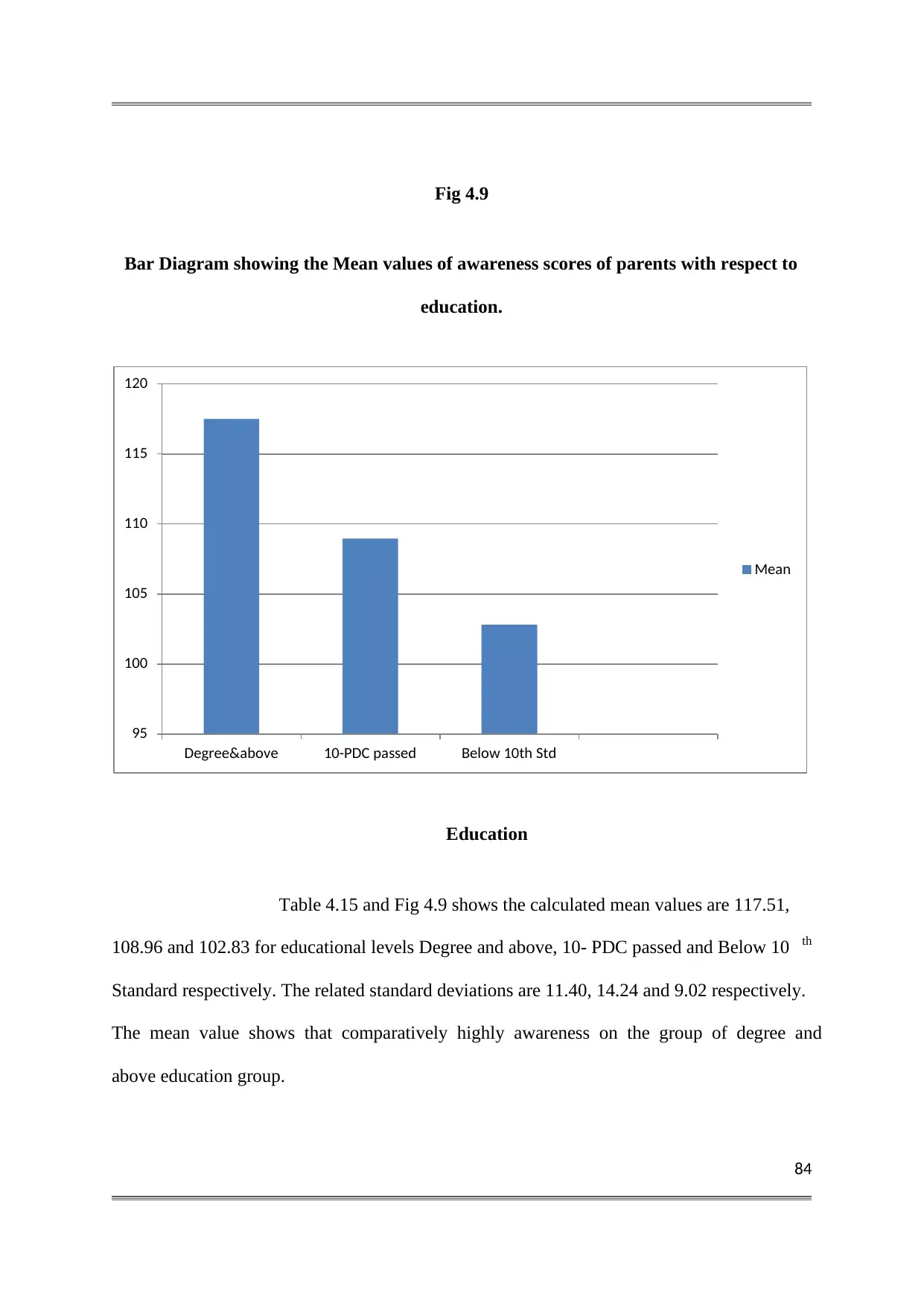

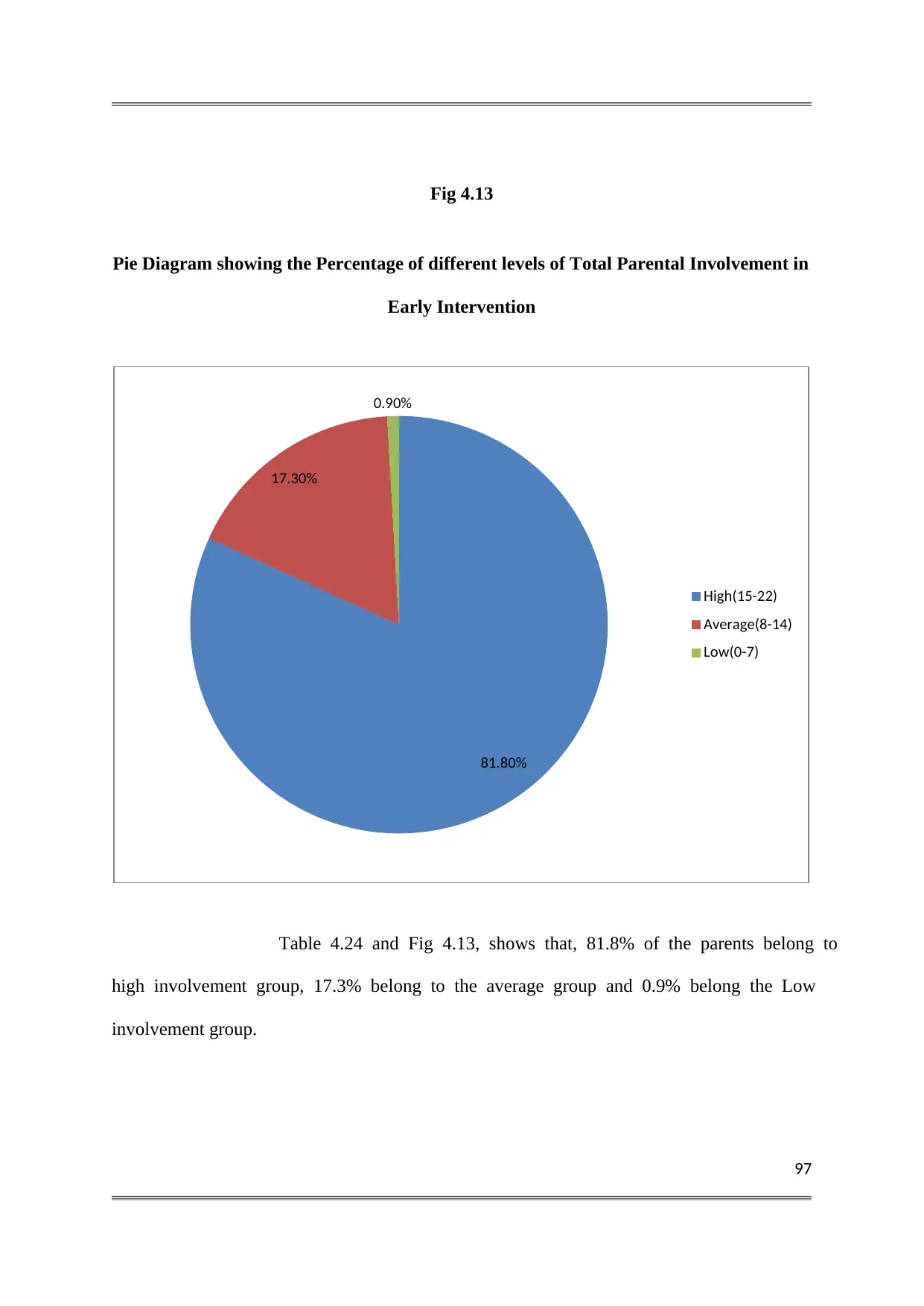

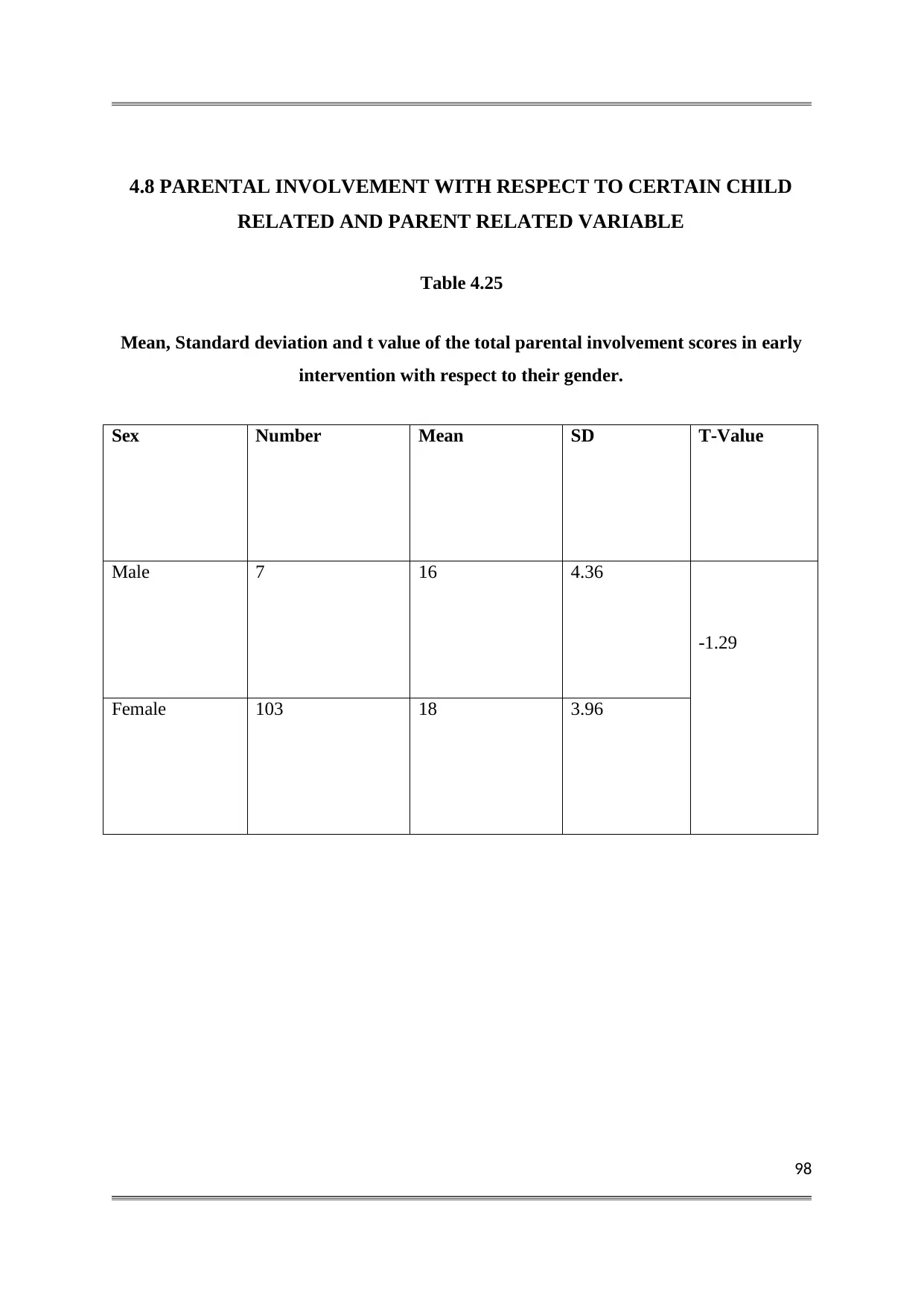

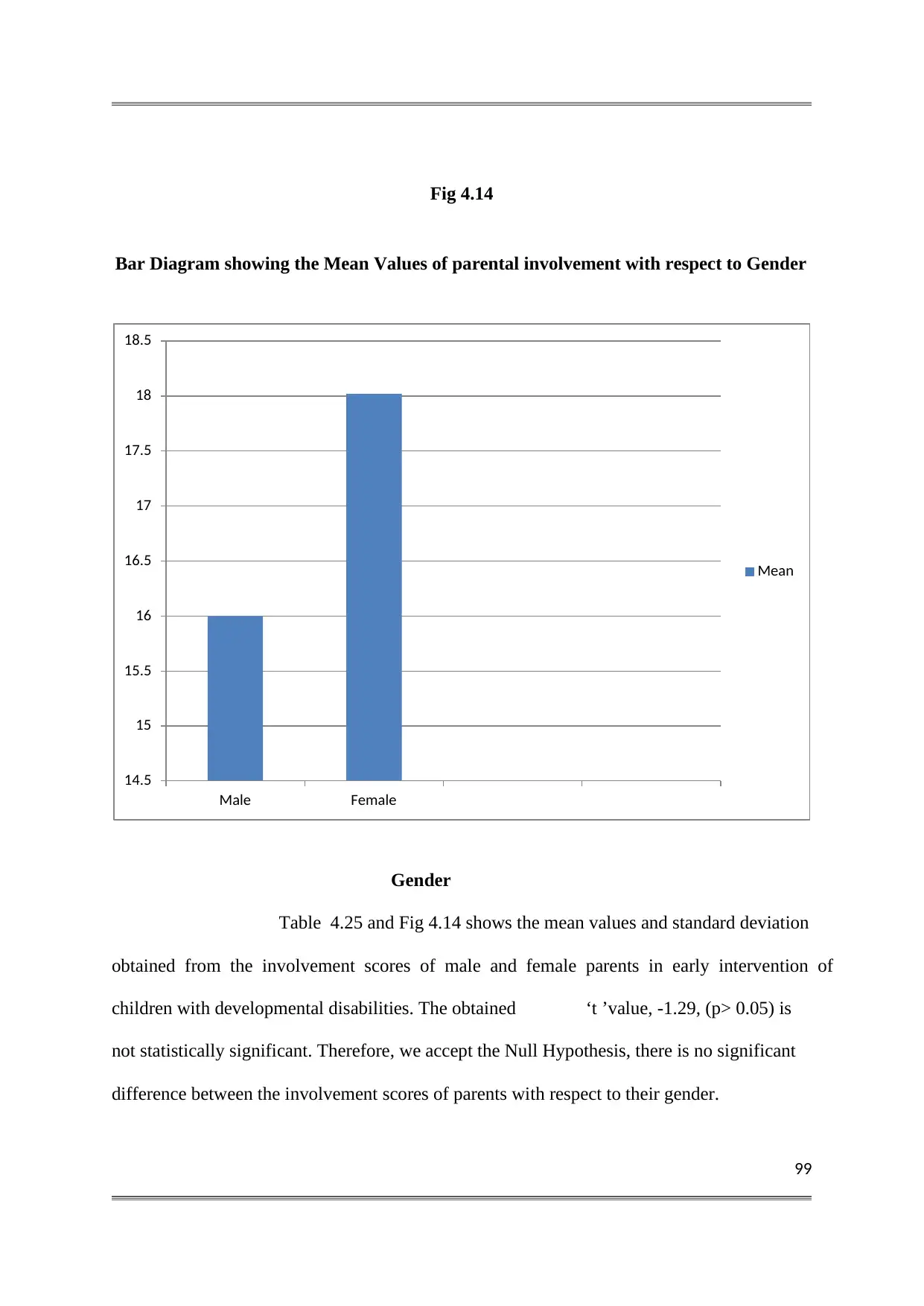

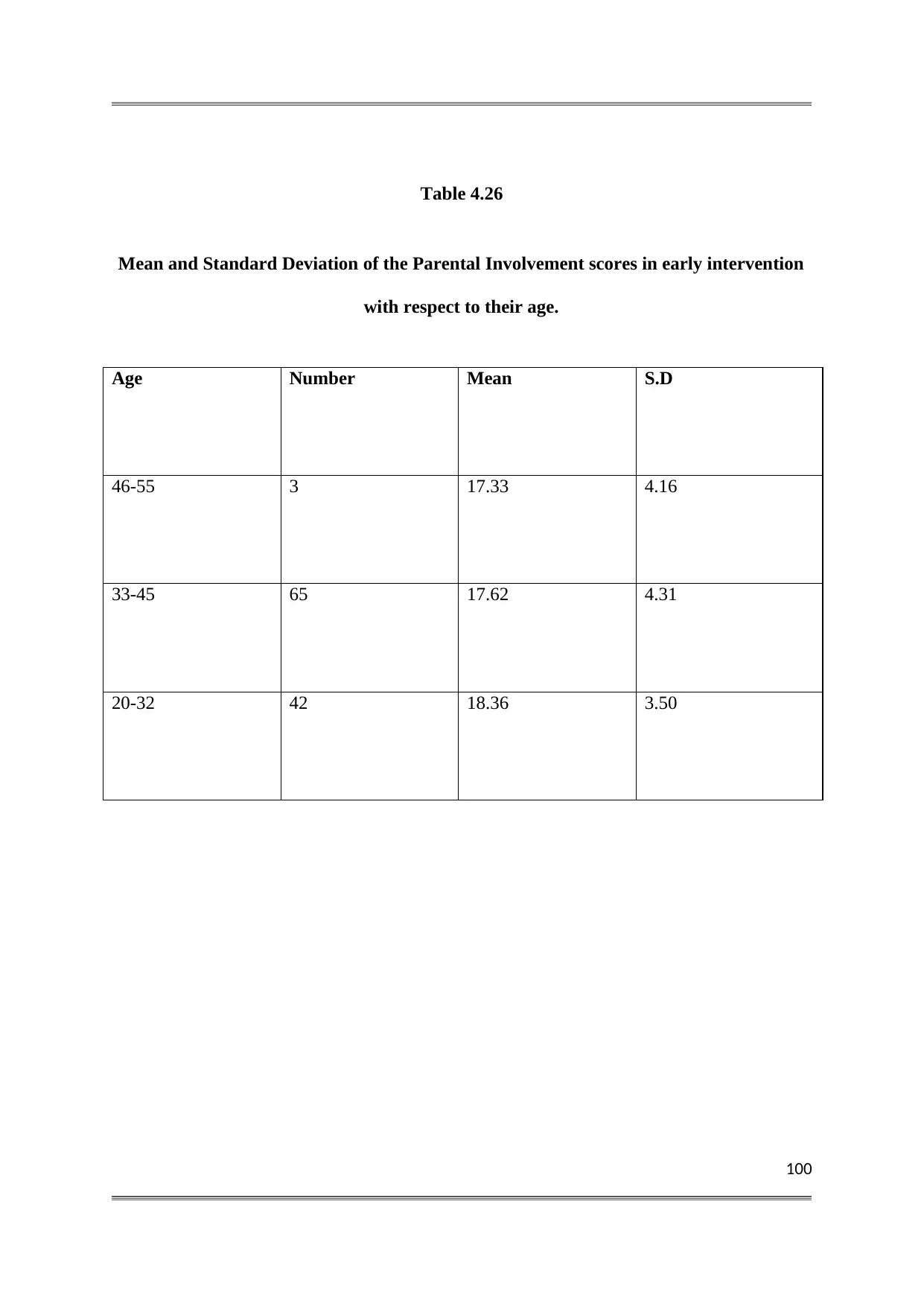

argued that the involvement of parents will reinforce and maintain the benefits of early