Onefinestay Case Study: Branding, Growth, and Competition in the Sharing Economy

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/16

|44

|14537

|486

Report

AI Summary

The provided content appears to be a collection of industry reports and news articles discussing the global hotels and resorts market, particularly in relation to luxury travel trends and the rise of alternative accommodation providers such as Airbnb. The reports and articles touch on topics including the growth of the luxury hotel industry, changing consumer preferences, and the impact of digital platforms on the hospitality sector.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

JILL AVERY ANAT KEINAN LIZ KIND

onefinestay

Miranda Cresswell was delighted to be helping Greg Marsh (HBS MBA

‘06), founder and CEO of onefinestay, a vacation home alternative to

fine hotels, with branding work for the company. onefinestay was

founded in September 2009 in London, and offered high-end home

rentals to travelers who sought a more authentic and local experience

than a typical upscale hotel might provide. The company equipped its

rental properties with luxury amenities such as fine linens and towels,

prestige brand toiletries such as Kiehl’s, and an iPhone loaded with

local maps and restaurant recommendations. By the fall of 2014,

onefinestay had approximately 250 full-time employees, and an

additional 250 contract staff. The company operated in four cities in

Europe and the U.S.

According to Marsh, onefinestay's brand had been "hacked" together

quickly during the company's early years. After five years of rapid

growth, Marsh brought Cresswell on board to do a comprehensive

analysis of the company's brand and its positioning in the marketplace.

Cresswell had spent several months gathering data and insights, and

was starting to experiment with use case scenarios that took a crack at

segmenting the company’s customers. The preliminary results were

interesting, but raised more questions than they answered, and

Cresswell wondered if this was the best way to segment the market.

While segmenting in this way was intriguing, it led to a branding

challenge – as a start-up, it was difficult for onefinestay to have the

resources to support multiple brand messages in the marketplace and

different segments wanted different things from their travel

experience. She pondered whether there were other ways to group

customers that would allow for a more universal positioning for the

brand or whether the company needed to focus on one or two

segments to serve.

Positioning the fledgling brand was a challenge. Who was the company

competing against and how could it carve out a unique value

proposition that would appeal to travelers and be differentiated from

onefinestay

Miranda Cresswell was delighted to be helping Greg Marsh (HBS MBA

‘06), founder and CEO of onefinestay, a vacation home alternative to

fine hotels, with branding work for the company. onefinestay was

founded in September 2009 in London, and offered high-end home

rentals to travelers who sought a more authentic and local experience

than a typical upscale hotel might provide. The company equipped its

rental properties with luxury amenities such as fine linens and towels,

prestige brand toiletries such as Kiehl’s, and an iPhone loaded with

local maps and restaurant recommendations. By the fall of 2014,

onefinestay had approximately 250 full-time employees, and an

additional 250 contract staff. The company operated in four cities in

Europe and the U.S.

According to Marsh, onefinestay's brand had been "hacked" together

quickly during the company's early years. After five years of rapid

growth, Marsh brought Cresswell on board to do a comprehensive

analysis of the company's brand and its positioning in the marketplace.

Cresswell had spent several months gathering data and insights, and

was starting to experiment with use case scenarios that took a crack at

segmenting the company’s customers. The preliminary results were

interesting, but raised more questions than they answered, and

Cresswell wondered if this was the best way to segment the market.

While segmenting in this way was intriguing, it led to a branding

challenge – as a start-up, it was difficult for onefinestay to have the

resources to support multiple brand messages in the marketplace and

different segments wanted different things from their travel

experience. She pondered whether there were other ways to group

customers that would allow for a more universal positioning for the

brand or whether the company needed to focus on one or two

segments to serve.

Positioning the fledgling brand was a challenge. Who was the company

competing against and how could it carve out a unique value

proposition that would appeal to travelers and be differentiated from

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

what was offered by other hospitality options? Was its current moniker

“the unhotel” working for or against it?

As a two-sided marketplace, onefinestay also struggled to find the

balance between meeting the needs of two customers: the homeowner

hosts who supplied the company's unique inventory of properties and

the guests who paid to stay there. At times, their interests were at

odds with one another. As Marsh and Creswell considered refinements

to their product strategy, they had toEducational consider how their product

and service offering differentially impacted the host and guest

experience.

The competitive landscape was heating up and Marsh was eager to

allocate marketing resources in a way that would generate substantial

returns and help scale the company. He had big ambitions for the

company, but wondered what the right growth strategy was. Should he

focus on increasing the breadth of onefinestay’s global reach by

expanding into more cities around the world or should he focus on

building depth by increasing market penetration in the cities in which

he was already operating?

The Founding of onefinestay

Marsh was born and raised in London, England. Following his

graduation Christ’s College, he worked for GF-X, a logistics

marketplace startup, in a variety of operations and marketing roles.

Following the completion of his MBA program at Harvard Business

School, he joined Index Ventures, a leading London-based venture

capital firm, as an associate on the IT investment team.

Marsh had just returned from a 2009 trip to Pisa, Italy when the idea

for onefinestay occurred to him. He had a “dreadful stay” in a “dreary

airport hotel,” but thoroughly enjoyed an out-of-the-way restaurant

recommended by a friend who had grown up in the area. Without the

friend's advice, Marsh recognized he would have missed out on a local

experience in lieu of the typical tourist attractions. At the same time,

after coming back to London and making his nightly walks home from

work, he couldn’t help but notice the many luxury residential

properties in the area that appeared empty for vast portions of the

“the unhotel” working for or against it?

As a two-sided marketplace, onefinestay also struggled to find the

balance between meeting the needs of two customers: the homeowner

hosts who supplied the company's unique inventory of properties and

the guests who paid to stay there. At times, their interests were at

odds with one another. As Marsh and Creswell considered refinements

to their product strategy, they had toEducational consider how their product

and service offering differentially impacted the host and guest

experience.

The competitive landscape was heating up and Marsh was eager to

allocate marketing resources in a way that would generate substantial

returns and help scale the company. He had big ambitions for the

company, but wondered what the right growth strategy was. Should he

focus on increasing the breadth of onefinestay’s global reach by

expanding into more cities around the world or should he focus on

building depth by increasing market penetration in the cities in which

he was already operating?

The Founding of onefinestay

Marsh was born and raised in London, England. Following his

graduation Christ’s College, he worked for GF-X, a logistics

marketplace startup, in a variety of operations and marketing roles.

Following the completion of his MBA program at Harvard Business

School, he joined Index Ventures, a leading London-based venture

capital firm, as an associate on the IT investment team.

Marsh had just returned from a 2009 trip to Pisa, Italy when the idea

for onefinestay occurred to him. He had a “dreadful stay” in a “dreary

airport hotel,” but thoroughly enjoyed an out-of-the-way restaurant

recommended by a friend who had grown up in the area. Without the

friend's advice, Marsh recognized he would have missed out on a local

experience in lieu of the typical tourist attractions. At the same time,

after coming back to London and making his nightly walks home from

work, he couldn’t help but notice the many luxury residential

properties in the area that appeared empty for vast portions of the

year. Marsh wondered, "Why are these places empty? Why are the

places where I would most want to stay if I was visiting a city the ones

where you can't get to stay?"1 He called it a “no light bulb moment,”

noting “the lights aren’t on because nobody is home.”

Marsh conducted research to see if anyone else was doing something

similar, and ran the idea by a colleague who encouraged him to start

the company. Marsh’s concept was to provide discerning travelers with

upscale home rental options that would be more authentic than hotels

and more reliable than other vacation rental choices. At the same time,

homeowners would earn extra income from their properties when they

otherwise would have stood vacant.2 Marsh elaborated further:

Our mission is not to destroy the hotel industry. However, a proportion

of travel— certainly the majority of leisure travel—is just infinitely

better and far more enriching to stay in a home than in a building that

is soulless and has been designed for transient occupancy.... What

we’re bringing to that rental sector is generally a curation and quality

and service control that you take for granted in some industries

including hotels and chain restaurants, but that you don’t find in this

much more informal sector of the economy or that you haven’t found

until now.3

In September 2009, Marsh left Index Ventures to co-found onefinestay

with Demetrios Zoppos and Tim Davey. Zoppos and Marsh had worked

together at GF-X, and Marsh knew Davey through his work as co-

founder and chief technology officer at one of Index Venture’s portfolio

companies. (See Exhibit 1 for management bios.) Marsh commented,

“With this business, I wouldn’t even have attempted something so

ambitious and complex without Demetrios and his operations expertise

and similarly with Tim and his experience: we simply couldn’t have

done this without our technology.”4

Together they raised approximately €200,000 from friends and family,

and launched onefinestay in May 2010. Marsh reflected, “We really did

have to beg, borrow, and steal to get the first half dozen homes on the

Web site to start the ball rolling. Another adage, fake it till you make it,

well, we faked it a bit—of the first half dozen homes, one was mine,

one was Demetrios’s, and one belonged to a friend who has never

rented it out and insisted that he was never going to—it’s long since

come off the site, may I say—but we needed calling cards.”5

places where I would most want to stay if I was visiting a city the ones

where you can't get to stay?"1 He called it a “no light bulb moment,”

noting “the lights aren’t on because nobody is home.”

Marsh conducted research to see if anyone else was doing something

similar, and ran the idea by a colleague who encouraged him to start

the company. Marsh’s concept was to provide discerning travelers with

upscale home rental options that would be more authentic than hotels

and more reliable than other vacation rental choices. At the same time,

homeowners would earn extra income from their properties when they

otherwise would have stood vacant.2 Marsh elaborated further:

Our mission is not to destroy the hotel industry. However, a proportion

of travel— certainly the majority of leisure travel—is just infinitely

better and far more enriching to stay in a home than in a building that

is soulless and has been designed for transient occupancy.... What

we’re bringing to that rental sector is generally a curation and quality

and service control that you take for granted in some industries

including hotels and chain restaurants, but that you don’t find in this

much more informal sector of the economy or that you haven’t found

until now.3

In September 2009, Marsh left Index Ventures to co-found onefinestay

with Demetrios Zoppos and Tim Davey. Zoppos and Marsh had worked

together at GF-X, and Marsh knew Davey through his work as co-

founder and chief technology officer at one of Index Venture’s portfolio

companies. (See Exhibit 1 for management bios.) Marsh commented,

“With this business, I wouldn’t even have attempted something so

ambitious and complex without Demetrios and his operations expertise

and similarly with Tim and his experience: we simply couldn’t have

done this without our technology.”4

Together they raised approximately €200,000 from friends and family,

and launched onefinestay in May 2010. Marsh reflected, “We really did

have to beg, borrow, and steal to get the first half dozen homes on the

Web site to start the ball rolling. Another adage, fake it till you make it,

well, we faked it a bit—of the first half dozen homes, one was mine,

one was Demetrios’s, and one belonged to a friend who has never

rented it out and insisted that he was never going to—it’s long since

come off the site, may I say—but we needed calling cards.”5

By late 2010, onefinestay was able to raise $3.7 million in a Series A

round led by Index Ventures, PROfounders Capital, and a number of

angel investors with experience in the travel and hospitality industries.

The company grew rapidly, signing 100 homeowners and increasing

revenue tenfold in 2011. Spurred by its success in London, in May

2012, onefinestay launched operations in New York City. One month

later, the company announced it raised $12.2 million in a Series B

round, led by the U.S. venture capital firm Canaan Partners, along with

participation from Index Ventures and PROfounders Capital. (See

Exhibit 2 for board member biographies.) (According to Marsh,

onefinestay had raised additional capital since 2012, but had not

disclosed its more recent funding events publicly.)

Boosted by tourism during the summer London Olympics, by the end of

2012, onefinestay had 1,000 member homes in New York and London,

and employed a team of more than 100 people. The company

continued to expand and refine its operations, and in September 2013,

launched in Los Angeles and Paris. onefinestay also began developing

partnerships with travel agents and corporate travel organizations. By

the fall of 2014, onefinestay had operations in four cities, with plans for

continued rapid expansion. The company had over 2,000 houses or

apartments to rent, with more than 5,000 rooms. In total, onefinestay

had a property portfolio worth over $5 billion.

The Rise of the Sharing Economy

The sharing economy (also known as “the peer-to-peer rental market”

or “collaborative consumption,” among other names) generally

referred to the exchange of assets or services among individuals, aided

by the Internet and smart phones. Since the mid- to late-2000s, the

use of technology and online market platforms was enabling

individuals to become part-time entrepreneurs, blurring the distinction

between consuming and producing. The best-known examples of

sharing economy companies included Uber and Lyft, the taxi-like ride-

sharing services; Airbnb, an accommodations rental platform; and

TaskRabbit, a marketplace for outsourcing small jobs and household

errands. Forbes estimated the revenue flowing through the sharing

economy would exceed $3.5 billion for 2013, with year-over-year

growth of more than 25%.6 Investors had taken notice and were

aggressively funding sharing economy companies. By October 2014,

round led by Index Ventures, PROfounders Capital, and a number of

angel investors with experience in the travel and hospitality industries.

The company grew rapidly, signing 100 homeowners and increasing

revenue tenfold in 2011. Spurred by its success in London, in May

2012, onefinestay launched operations in New York City. One month

later, the company announced it raised $12.2 million in a Series B

round, led by the U.S. venture capital firm Canaan Partners, along with

participation from Index Ventures and PROfounders Capital. (See

Exhibit 2 for board member biographies.) (According to Marsh,

onefinestay had raised additional capital since 2012, but had not

disclosed its more recent funding events publicly.)

Boosted by tourism during the summer London Olympics, by the end of

2012, onefinestay had 1,000 member homes in New York and London,

and employed a team of more than 100 people. The company

continued to expand and refine its operations, and in September 2013,

launched in Los Angeles and Paris. onefinestay also began developing

partnerships with travel agents and corporate travel organizations. By

the fall of 2014, onefinestay had operations in four cities, with plans for

continued rapid expansion. The company had over 2,000 houses or

apartments to rent, with more than 5,000 rooms. In total, onefinestay

had a property portfolio worth over $5 billion.

The Rise of the Sharing Economy

The sharing economy (also known as “the peer-to-peer rental market”

or “collaborative consumption,” among other names) generally

referred to the exchange of assets or services among individuals, aided

by the Internet and smart phones. Since the mid- to late-2000s, the

use of technology and online market platforms was enabling

individuals to become part-time entrepreneurs, blurring the distinction

between consuming and producing. The best-known examples of

sharing economy companies included Uber and Lyft, the taxi-like ride-

sharing services; Airbnb, an accommodations rental platform; and

TaskRabbit, a marketplace for outsourcing small jobs and household

errands. Forbes estimated the revenue flowing through the sharing

economy would exceed $3.5 billion for 2013, with year-over-year

growth of more than 25%.6 Investors had taken notice and were

aggressively funding sharing economy companies. By October 2014,

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Uber had raised $1.5 billion, and had an implied valuation of $17

billion, more than rental car market leaders Hertz and Avis combined.

Airbnb had raised $795 million, and had an implied valuation of $10

billion, more than the market value of Hyatt Hotels, a leading

hospitality company with 549 properties around the world. Shervin

Pishevar, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist argued, “This is a

movement as important as when the Web browser came out.”7

Nonetheless, observers recognized the challenges faced by sharing

economy companies, including establishing trust, providing

demonstrated value, and addressing the “chicken-and-egg” problem of

ensuring enough supply and demand. Investor and entrepreneur Raj

Kapoor also pointed out the need for consistency of service in the

offline experience, particularly during a sharing economy company's

early days.8 Perhaps the biggest hurdles for sharing economy

companies were the legal and regulatory issues, since most existing

laws had been established for traditional large-scale organizations, and

were primarily set at state and city, rather than national, levels. Some

locales such as San Francisco, Washington DC, and the United

Kingdom were developing regulations to support the sharing economy

and encourage economic growth, while other regions were moving

more cautiously. By the fall of 2014, Airbnb remained in a contentious

battle with New York state regulators, and many other cities and

countries were grappling with the tax, legal, insurance and policy

issues raised by sharing economy companies.

Managing a Two-Sided Marketplace

While people often described onefinestay as a “high-end Airbnb,”

Marsh disagreed with the comparison. He noted, “We don’t think we

compete with Airbnb any more than Marriott competes with Expedia.”

Marsh pointed to onefinestay’s collection of carefully curated homes

and apartments, its attention to detail—similar to that of a high-end

hotel—and the fact that guests never interacted with hosts as

distinguishing characteristics. In addition, Marsh saw onefinestay as “a

vertically- integrated service-enabled market, providing a variety of

value-add on top of a brokerage piece. What we’re doing behind the

scenes to create that market and then service and support it, is

actually almost more important than the market itself. We’re not a

distribution business, we’re a manufacturing business.” He further

billion, more than rental car market leaders Hertz and Avis combined.

Airbnb had raised $795 million, and had an implied valuation of $10

billion, more than the market value of Hyatt Hotels, a leading

hospitality company with 549 properties around the world. Shervin

Pishevar, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist argued, “This is a

movement as important as when the Web browser came out.”7

Nonetheless, observers recognized the challenges faced by sharing

economy companies, including establishing trust, providing

demonstrated value, and addressing the “chicken-and-egg” problem of

ensuring enough supply and demand. Investor and entrepreneur Raj

Kapoor also pointed out the need for consistency of service in the

offline experience, particularly during a sharing economy company's

early days.8 Perhaps the biggest hurdles for sharing economy

companies were the legal and regulatory issues, since most existing

laws had been established for traditional large-scale organizations, and

were primarily set at state and city, rather than national, levels. Some

locales such as San Francisco, Washington DC, and the United

Kingdom were developing regulations to support the sharing economy

and encourage economic growth, while other regions were moving

more cautiously. By the fall of 2014, Airbnb remained in a contentious

battle with New York state regulators, and many other cities and

countries were grappling with the tax, legal, insurance and policy

issues raised by sharing economy companies.

Managing a Two-Sided Marketplace

While people often described onefinestay as a “high-end Airbnb,”

Marsh disagreed with the comparison. He noted, “We don’t think we

compete with Airbnb any more than Marriott competes with Expedia.”

Marsh pointed to onefinestay’s collection of carefully curated homes

and apartments, its attention to detail—similar to that of a high-end

hotel—and the fact that guests never interacted with hosts as

distinguishing characteristics. In addition, Marsh saw onefinestay as “a

vertically- integrated service-enabled market, providing a variety of

value-add on top of a brokerage piece. What we’re doing behind the

scenes to create that market and then service and support it, is

actually almost more important than the market itself. We’re not a

distribution business, we’re a manufacturing business.” He further

described onefinestay as “a hospitality company and also a very

complex logistics company behind the scenes.”9

Homeowner Hosts: Managing the Supply Side

Most of the properties listed on onefinestay were homeowners’ primary

residences. Marsh commented, "The homeowners might travel for a

month or two, they might have work that takes them overseas, they

might have a second home in the south of France or whatever. It’s

even more important in those situations that they’re emotionally

comfortable with onefinestay and the guests that we introduce to their

properties, and [that we] manage them on their behalf as a very, very

credible service partner. There’s lots of stuff we’re doing behind the

scenes to earn that trust.”10 He elaborated further on a homeowner’s

decision to join onefinestay:

It’s not only about money. Of course, people wouldn’t be likely to do it

if there were no money or emotional benefits involved. The average

onefinestay member probably earns a household income of $250,000 a

year and their property is worth ten times that. It’s not like an extra

few thousand dollars a year is going to fundamentally transform their

lives. But, if it’s free money, and someone else is doing all the work, all

you have to do is overcome the anxieties and the trust issues around

affiliating. When you get your home back after your vacation cleaner

than you left it, you stop asking yourself, ‘Well, why the heck would I

do that?’ and you start thinking ‘Well, why wouldn’t I do that?’

Homeowner members were required to list exclusively through

onefinestay and were expected to make their homes available to the

company for at least four weeks per year. Two-thirds of onefinestay’s

homeowner members came through word-of-mouth referral. Keyvan

Nilforoushan, onefinestay’s Paris general manager noted, “I know to

expect three calls on a Sunday from people who’ve been out to dinner

on Saturday night with one of our hosts. When hosts come back from

holiday, that’s when it happens.”11 Marsh reiterated the importance of

social validation and noted that most decision makers on the supply

side were female, "Often it’s one mom talking to another mom at the

school gates. We realized that if we could figure out how to make

things sufficiently easy and compelling for folks who would not

otherwise do this, we could bring a tier of inventory to the market

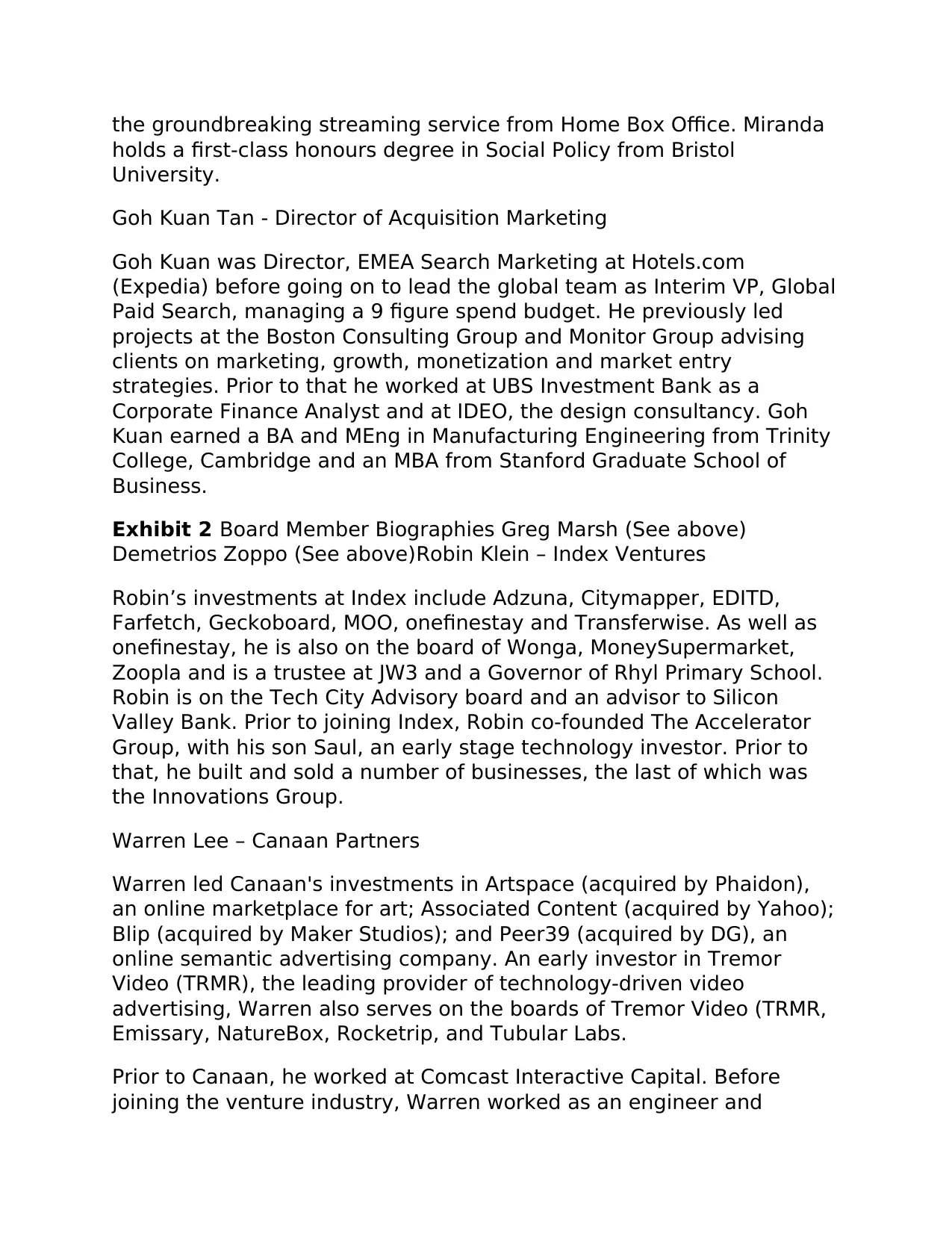

that’s never previously been available.” (See Exhibit 3 for additional

complex logistics company behind the scenes.”9

Homeowner Hosts: Managing the Supply Side

Most of the properties listed on onefinestay were homeowners’ primary

residences. Marsh commented, "The homeowners might travel for a

month or two, they might have work that takes them overseas, they

might have a second home in the south of France or whatever. It’s

even more important in those situations that they’re emotionally

comfortable with onefinestay and the guests that we introduce to their

properties, and [that we] manage them on their behalf as a very, very

credible service partner. There’s lots of stuff we’re doing behind the

scenes to earn that trust.”10 He elaborated further on a homeowner’s

decision to join onefinestay:

It’s not only about money. Of course, people wouldn’t be likely to do it

if there were no money or emotional benefits involved. The average

onefinestay member probably earns a household income of $250,000 a

year and their property is worth ten times that. It’s not like an extra

few thousand dollars a year is going to fundamentally transform their

lives. But, if it’s free money, and someone else is doing all the work, all

you have to do is overcome the anxieties and the trust issues around

affiliating. When you get your home back after your vacation cleaner

than you left it, you stop asking yourself, ‘Well, why the heck would I

do that?’ and you start thinking ‘Well, why wouldn’t I do that?’

Homeowner members were required to list exclusively through

onefinestay and were expected to make their homes available to the

company for at least four weeks per year. Two-thirds of onefinestay’s

homeowner members came through word-of-mouth referral. Keyvan

Nilforoushan, onefinestay’s Paris general manager noted, “I know to

expect three calls on a Sunday from people who’ve been out to dinner

on Saturday night with one of our hosts. When hosts come back from

holiday, that’s when it happens.”11 Marsh reiterated the importance of

social validation and noted that most decision makers on the supply

side were female, "Often it’s one mom talking to another mom at the

school gates. We realized that if we could figure out how to make

things sufficiently easy and compelling for folks who would not

otherwise do this, we could bring a tier of inventory to the market

that’s never previously been available.” (See Exhibit 3 for additional

information on onefinestay’s member hosts.) Marsh explained the

process of signing up homeowners:

The “take-on” process starts when the owner first joins. It’s not one

single interaction, but takes place over a period of a few weeks.

Homeowners may have heard about us from a direct mail marketing,

through an editorial piece, or increasingly, from a friend or an

associate at work. We go to visit them in their home. The visit is

basically a sales meeting, in the sense that we are trying to persuade

them in a very general and soft way, to join the service. We’re almost

discouraging folks from membership unless we’re really convinced it’s

going to be valuable for them and for us over the medium- to long-

term.

Marsh estimated the company listed approximately one in ten of the

properties offered to them. He explained, "People get anxious that

we're the taste police, but it's rarely a question of taste. Our issues are

much more likely to be practical, like is it a good location, does

everything work properly?”12 A third co-founder and president of the

Americas, Evan Frank added, “The homes need to have WiFi, they

need to have bathrooms and kitchens in really good condition, and

they need to have character. It has to look like somebody lives there

and that the owner has a personality. What we don’t want are homes

that look like standard hotel rooms or apartments. Whether it’s nice

furniture, great views, interesting pictures on the walls, you have to

walk into the home and think there's something special about it."13

Once onefinestay and a homeowner decided to move forward, the next

part of the take-on process was called the registration phase. It took

place again, on premises, in order to register the homeowner’s assets.

A representative from onefinestay went in with a scanner and created

an extensive and detailed inventory of the property—information about

everything in the home and where it was located, down to the rules

and exceptions of the owner. Marsh added, “That might include

instructions such as not to use an abrasive surface cleaner on the

downstairs table. It might also include information about which

bookshelves or wardrobes to seal off, and which spare room should be

used for storage.”

The meetings typically lasted a few hours, and for a large property,

could take significantly longer. As Marsh noted, “Ultimately, we need to

process of signing up homeowners:

The “take-on” process starts when the owner first joins. It’s not one

single interaction, but takes place over a period of a few weeks.

Homeowners may have heard about us from a direct mail marketing,

through an editorial piece, or increasingly, from a friend or an

associate at work. We go to visit them in their home. The visit is

basically a sales meeting, in the sense that we are trying to persuade

them in a very general and soft way, to join the service. We’re almost

discouraging folks from membership unless we’re really convinced it’s

going to be valuable for them and for us over the medium- to long-

term.

Marsh estimated the company listed approximately one in ten of the

properties offered to them. He explained, "People get anxious that

we're the taste police, but it's rarely a question of taste. Our issues are

much more likely to be practical, like is it a good location, does

everything work properly?”12 A third co-founder and president of the

Americas, Evan Frank added, “The homes need to have WiFi, they

need to have bathrooms and kitchens in really good condition, and

they need to have character. It has to look like somebody lives there

and that the owner has a personality. What we don’t want are homes

that look like standard hotel rooms or apartments. Whether it’s nice

furniture, great views, interesting pictures on the walls, you have to

walk into the home and think there's something special about it."13

Once onefinestay and a homeowner decided to move forward, the next

part of the take-on process was called the registration phase. It took

place again, on premises, in order to register the homeowner’s assets.

A representative from onefinestay went in with a scanner and created

an extensive and detailed inventory of the property—information about

everything in the home and where it was located, down to the rules

and exceptions of the owner. Marsh added, “That might include

instructions such as not to use an abrasive surface cleaner on the

downstairs table. It might also include information about which

bookshelves or wardrobes to seal off, and which spare room should be

used for storage.”

The meetings typically lasted a few hours, and for a large property,

could take significantly longer. As Marsh noted, “Ultimately, we need to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

be able to deal with any issues that arise in that home, so we can

manage the property as if the owner didn’t exist.” The next step was

the photo shoot. onefinestay merchandised the property, wrote copy,

and presented images of it on the company’s Web site. Marsh

commented, “We’ve actually done a lot of process engineering to get

the quality consistently excellent at a sensible cost.” Typically, the first

reservation occurred within just a few weeks since homeowners often

signed up with onefinestay in anticipation of an overseas or extended

trip. According to Marsh:

This is where the fun part starts. Once the homeowner leaves town,

the property’s essentially under our control. We go into the home and

we stage it. We call that provisioning. We run through the original

checklist and it’s almost like an episode of CSI. We bag and tag things,

and when needed move stuff around. We do a little bit of de-cluttering

and we usually seal off a spare room or some of the wardrobes and

cabinetry with little bar-coded, tamper evident seals. They serve as a

nudge to remind guests to be considerate during their stay. There’s a

deep clean, including fresh hotel- grade thread-count linen sheets on

the bed, plush towels in the restrooms, and fancy bathroom products—

Kiehl’s in New York, Aesop in London, and L'Occitane in France.

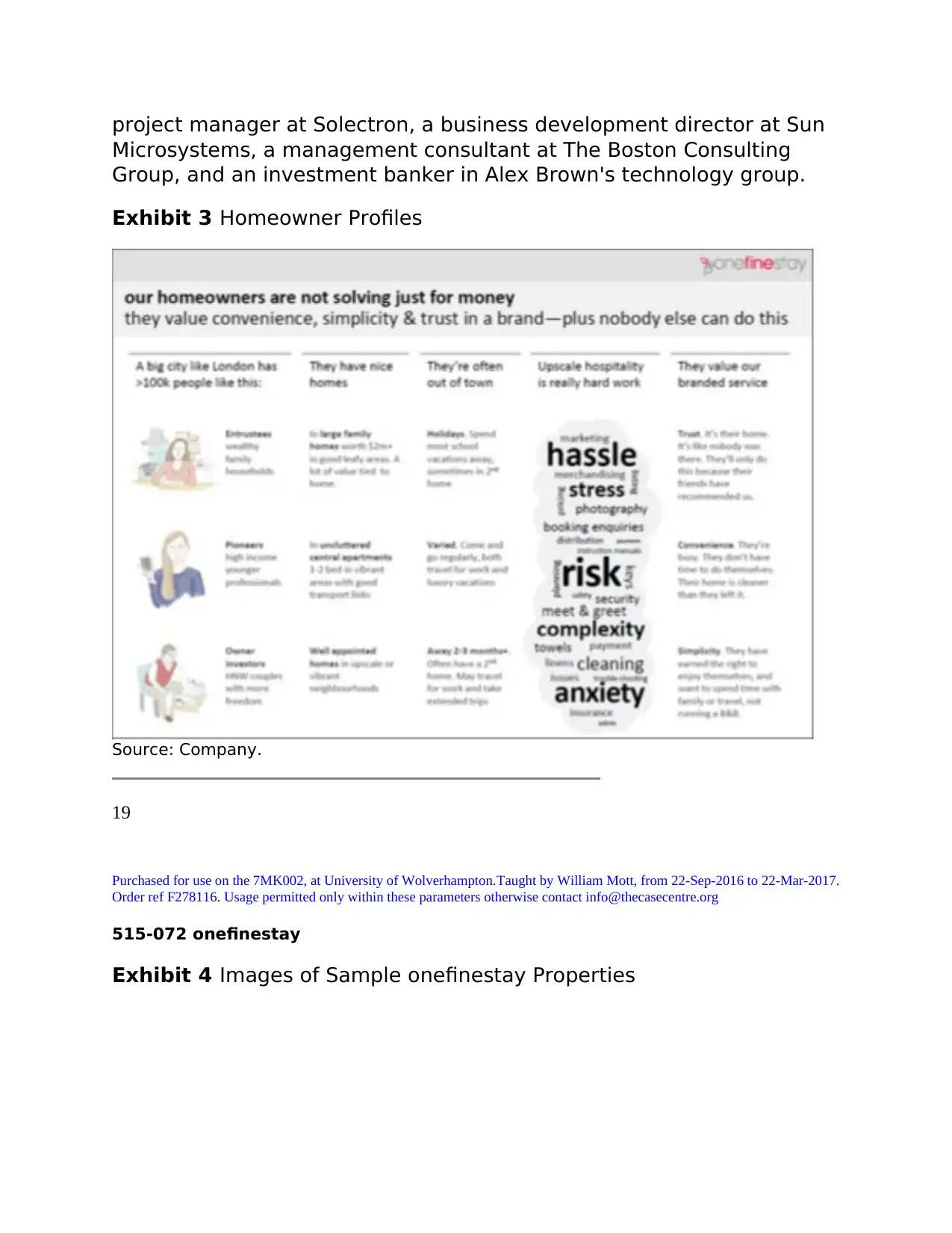

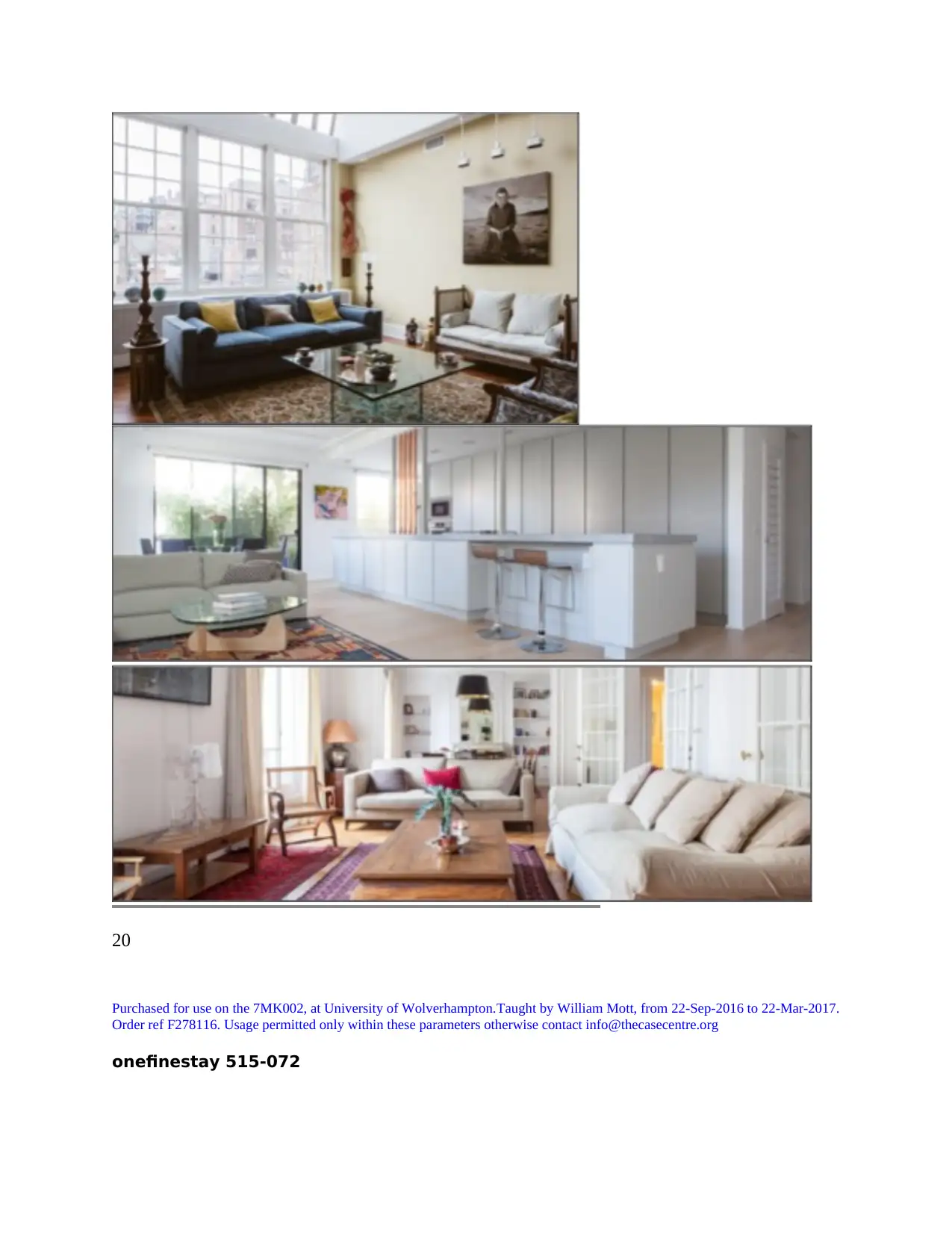

The homes included in onefinestay's portfolio were distinctive.

Examples included a former sugar warehouse in New York City with

views across the Hudson River, a three-story loft in a former rectory in

New York’s Murray Hill neighborhood, and a two-bedroom apartment in

London’s St. Pancras railway station’s clock tower. (See Exhibit 4 for

images of sample properties.) Prices ranged

5

Educational material supplied by The Case Centre Copyright encoded A76HM-JUJ9K-PJMN9I Order reference F278116

from $250 per night for a comfortable one bedroom apartment to well

over $2,500 per night for a grand townhouse. Pricing for homeowners

was negotiated up front and then marked up by onefinestay before

being posted online. As one reporter noted, “The beauty of

onefinestay...is that you stay in the kind of place you’d like to live in,

but probably can't afford.”14

Attracting Guests: Managing the Demand Side

manage the property as if the owner didn’t exist.” The next step was

the photo shoot. onefinestay merchandised the property, wrote copy,

and presented images of it on the company’s Web site. Marsh

commented, “We’ve actually done a lot of process engineering to get

the quality consistently excellent at a sensible cost.” Typically, the first

reservation occurred within just a few weeks since homeowners often

signed up with onefinestay in anticipation of an overseas or extended

trip. According to Marsh:

This is where the fun part starts. Once the homeowner leaves town,

the property’s essentially under our control. We go into the home and

we stage it. We call that provisioning. We run through the original

checklist and it’s almost like an episode of CSI. We bag and tag things,

and when needed move stuff around. We do a little bit of de-cluttering

and we usually seal off a spare room or some of the wardrobes and

cabinetry with little bar-coded, tamper evident seals. They serve as a

nudge to remind guests to be considerate during their stay. There’s a

deep clean, including fresh hotel- grade thread-count linen sheets on

the bed, plush towels in the restrooms, and fancy bathroom products—

Kiehl’s in New York, Aesop in London, and L'Occitane in France.

The homes included in onefinestay's portfolio were distinctive.

Examples included a former sugar warehouse in New York City with

views across the Hudson River, a three-story loft in a former rectory in

New York’s Murray Hill neighborhood, and a two-bedroom apartment in

London’s St. Pancras railway station’s clock tower. (See Exhibit 4 for

images of sample properties.) Prices ranged

5

Educational material supplied by The Case Centre Copyright encoded A76HM-JUJ9K-PJMN9I Order reference F278116

from $250 per night for a comfortable one bedroom apartment to well

over $2,500 per night for a grand townhouse. Pricing for homeowners

was negotiated up front and then marked up by onefinestay before

being posted online. As one reporter noted, “The beauty of

onefinestay...is that you stay in the kind of place you’d like to live in,

but probably can't afford.”14

Attracting Guests: Managing the Demand Side

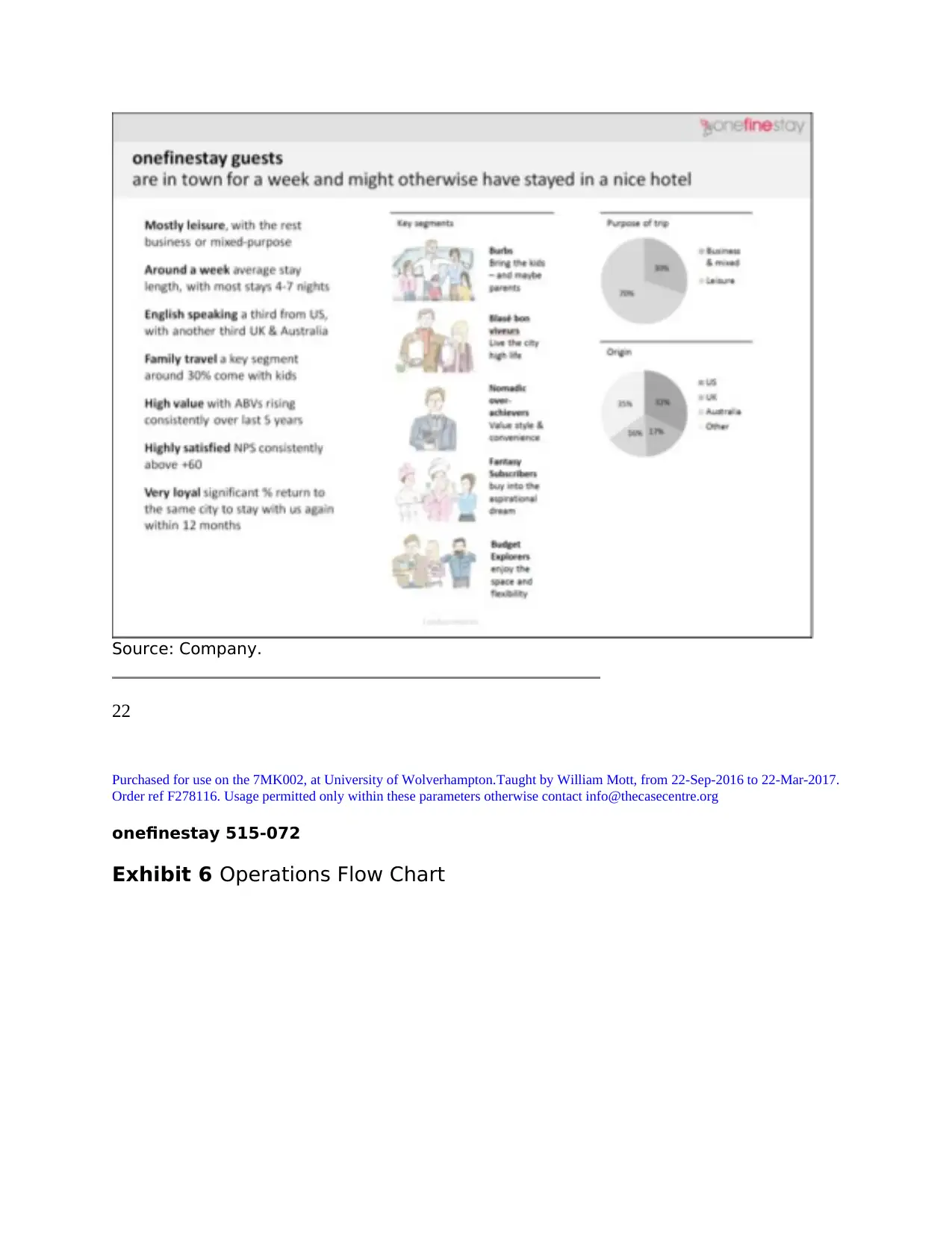

Approximately 70% of onefinestay’s guest customers were leisure

travelers, and the remaining 30% were business or mixed-purpose

travelers. Frank noted, ““[We cater to] a wide variety. There are a lot

of families and business travelers. They are the type of people who

would otherwise stay in a higher-end hotel at a four-star price point."15

The vast majority of guests booked their stays with the company

online, about half the time with phone or email assistance from a

onefinestay guest sales representative. Historically, approximately

80% of onefinestay guests learned of the company during a Google

search. However, by the fall of 2014, it was a much more blended

picture, with bookings coming from a range of online and offline

channels, alongside a high proportion of organic (unpaid) traffic. (See

Exhibit 5 for more data on onefinestay guests.)

The travel agent channel was relatively new for onefinestay. Corporate

travel departments used onefinestay primarily for relocations and

consultants who came to a city on repeat business.16 While the

majority of onefinestay’s properties had multiple bedrooms, some were

single-room apartments. By the fall of 2014, one-third of the

company’s channel business was with traditional, offline travel

organizations such as Virtuoso, while two-thirds was with online

organizations such as Booking.com, Expedia, and HomeAway. In the

hotel sector, travel agency fees typically ranged from 10% to 12%.

Marsh commented, “It’s not free, but it is scalable. Referral behavior

within the travel agent community is very, very strong. We have a

unique product and if we’re successful in educating that channel, we

think it’s very, very powerful and a great opportunity for us.”

A typical guest might stay around a week, paying in the region of

$600-700 per night for the experience. (Channel sales through travel

agencies, carried a higher average ticket of approximately $7,000 per

stay.) Travelers generally reserved properties well in advance of

arrival, typically paying by credit card and providing flight details. The

company had a “meet and greeter” to meet guest travelers onsite

when the guests arrived. The meet and greeter helped guests with

their bags, handed over the keys, showed them the iPhone, and

explained the house rules. Marsh noted, “We lend guests an iPhone

because most people have a smartphone, but they often don’t have

local data packages, so it’s extremely expensive to use that device

when they’re traveling.”17 The iPhone also included onefinestay’s own

travelers, and the remaining 30% were business or mixed-purpose

travelers. Frank noted, ““[We cater to] a wide variety. There are a lot

of families and business travelers. They are the type of people who

would otherwise stay in a higher-end hotel at a four-star price point."15

The vast majority of guests booked their stays with the company

online, about half the time with phone or email assistance from a

onefinestay guest sales representative. Historically, approximately

80% of onefinestay guests learned of the company during a Google

search. However, by the fall of 2014, it was a much more blended

picture, with bookings coming from a range of online and offline

channels, alongside a high proportion of organic (unpaid) traffic. (See

Exhibit 5 for more data on onefinestay guests.)

The travel agent channel was relatively new for onefinestay. Corporate

travel departments used onefinestay primarily for relocations and

consultants who came to a city on repeat business.16 While the

majority of onefinestay’s properties had multiple bedrooms, some were

single-room apartments. By the fall of 2014, one-third of the

company’s channel business was with traditional, offline travel

organizations such as Virtuoso, while two-thirds was with online

organizations such as Booking.com, Expedia, and HomeAway. In the

hotel sector, travel agency fees typically ranged from 10% to 12%.

Marsh commented, “It’s not free, but it is scalable. Referral behavior

within the travel agent community is very, very strong. We have a

unique product and if we’re successful in educating that channel, we

think it’s very, very powerful and a great opportunity for us.”

A typical guest might stay around a week, paying in the region of

$600-700 per night for the experience. (Channel sales through travel

agencies, carried a higher average ticket of approximately $7,000 per

stay.) Travelers generally reserved properties well in advance of

arrival, typically paying by credit card and providing flight details. The

company had a “meet and greeter” to meet guest travelers onsite

when the guests arrived. The meet and greeter helped guests with

their bags, handed over the keys, showed them the iPhone, and

explained the house rules. Marsh noted, “We lend guests an iPhone

because most people have a smartphone, but they often don’t have

local data packages, so it’s extremely expensive to use that device

when they’re traveling.”17 The iPhone also included onefinestay’s own

app with a ‘contact us’ button so that guests could contact onefinestay

anytime during their stay. Marsh added, “From then on in, the guest is

on their own except for periodic maid service, usually once every

week. Then, when the last set of guests leave during a specific rental

period, we go back in and reverse all those set up steps so the owner

finds their place like they left it. Actually, they probably find it a bit

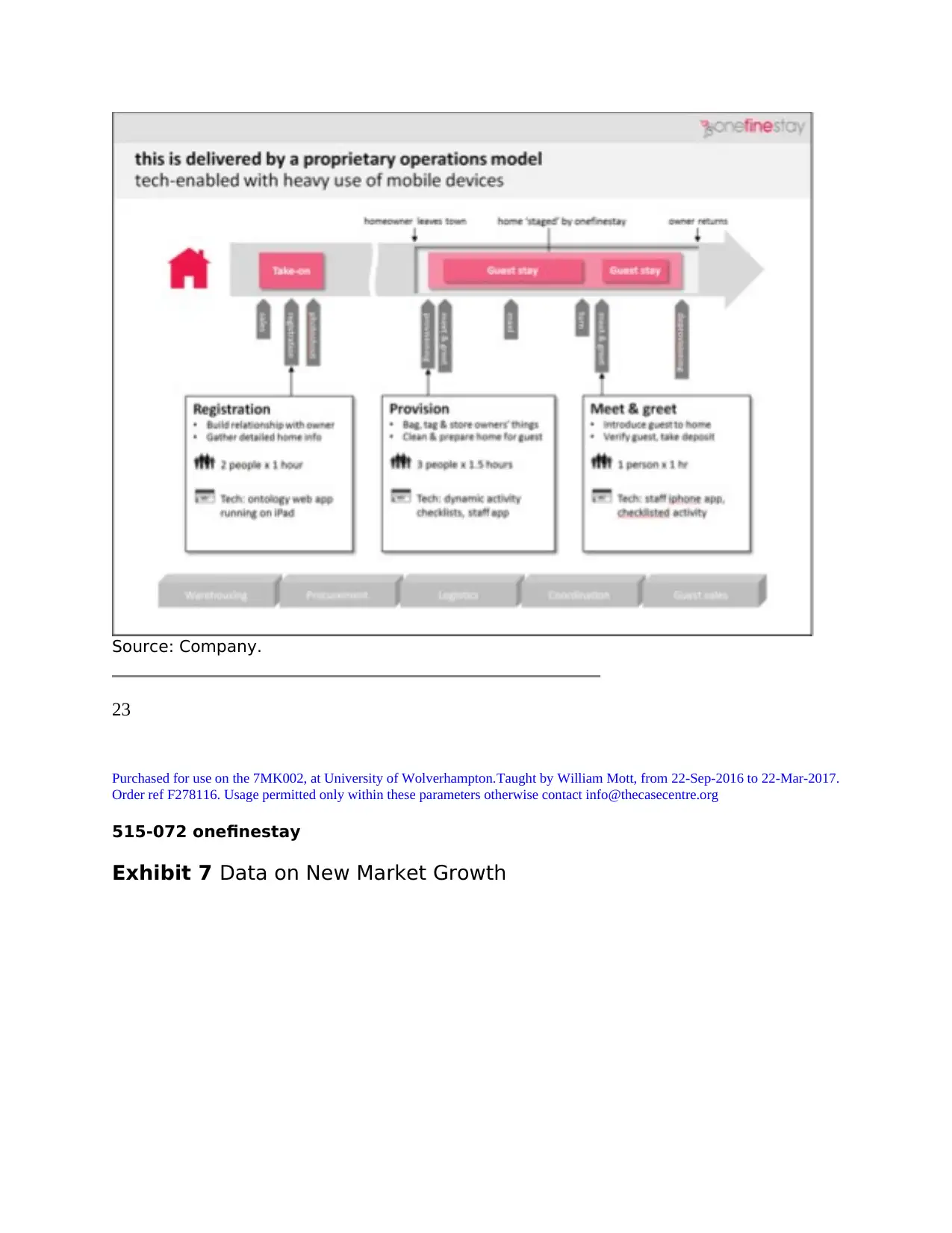

cleaner.” (See Exhibit 6 for a flow chart of onefinestay’s operations

process.)

Onefinestay’s net promoter scoresa for both guests and hosts—

consistently between 60 and 70— were extremely high, particularly for

the hospitality sector. Other feedback was generally positive as well,

although as one guest commented, "For the practically challenged,

there are downsides to living

like a local. Locks and keys, light switches and alien TV and alarm

systems are not my friends."18 According to Marsh, guest loyalty

appeared strong to date.

The onefinestay Virtual Marketplace

The onefinestay Web site functioned as its virtual storefront, attracting

and serving both sides— homeowners and travelers—of the two-sided

marketplace. The company’s home page was geared primarily toward

guests, with glossy images of sample properties, media logos from

high profile news and travel publications that had covered the

company, and folios to assist guests with beginning the home search

process. Other pages provided guest testimonials and additional

content on onefinestay’s unique offerings and amenities. A separate

tab was dedicated to potential hosts. In addition to a general overview,

two videos highlighted onefinestay’s ease of use and financial and

other benefits from different homeowners’ perspectives. Marsh

commented on the company’s digital presence:

Although we don’t think of onefinestay as a web business, our online

storefront is clearly the most salient introduction that most customers

will have to our brand and proposition. It’s also almost the only way

you can effectively communicate the specifics of a unique home, so

the site is really doing three things: it’s educating people about a new

category of accommodation, it’s introducing them to our branded

service promise within that new category, and it’s a point of a sale for

anytime during their stay. Marsh added, “From then on in, the guest is

on their own except for periodic maid service, usually once every

week. Then, when the last set of guests leave during a specific rental

period, we go back in and reverse all those set up steps so the owner

finds their place like they left it. Actually, they probably find it a bit

cleaner.” (See Exhibit 6 for a flow chart of onefinestay’s operations

process.)

Onefinestay’s net promoter scoresa for both guests and hosts—

consistently between 60 and 70— were extremely high, particularly for

the hospitality sector. Other feedback was generally positive as well,

although as one guest commented, "For the practically challenged,

there are downsides to living

like a local. Locks and keys, light switches and alien TV and alarm

systems are not my friends."18 According to Marsh, guest loyalty

appeared strong to date.

The onefinestay Virtual Marketplace

The onefinestay Web site functioned as its virtual storefront, attracting

and serving both sides— homeowners and travelers—of the two-sided

marketplace. The company’s home page was geared primarily toward

guests, with glossy images of sample properties, media logos from

high profile news and travel publications that had covered the

company, and folios to assist guests with beginning the home search

process. Other pages provided guest testimonials and additional

content on onefinestay’s unique offerings and amenities. A separate

tab was dedicated to potential hosts. In addition to a general overview,

two videos highlighted onefinestay’s ease of use and financial and

other benefits from different homeowners’ perspectives. Marsh

commented on the company’s digital presence:

Although we don’t think of onefinestay as a web business, our online

storefront is clearly the most salient introduction that most customers

will have to our brand and proposition. It’s also almost the only way

you can effectively communicate the specifics of a unique home, so

the site is really doing three things: it’s educating people about a new

category of accommodation, it’s introducing them to our branded

service promise within that new category, and it’s a point of a sale for

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

the particular homes that we market in the cities where we operate.

It’s the antithesis of a transactional purchase: big ticket vacation travel

is a deliberative, considered, consultative purchase which will take

days or even weeks to consummate. Our typical guest or guest group

will visit our site many, many times, from multiple devices, before

making a final decision. That’s why we have a fully staffed follow-the-

sun inbound sales organization: at this price point and service level,

some people want support if only to provide comfort that we’re the

‘real deal’. A complex purchase path in a novel category makes it

especially difficult to get insight from traditional web analytics tools,

which are designed for simpler, more transactional small basket

commodity shopping. That in turn means determining the efficient

frontier for paid search acquisition, say, is quite a subtle and nuanced

analytical problem.

Expansion Plans

onefinestay’s launch in New York City was the first step in its broader

strategy of international expansion. Marsh’s plan was to test and fine-

tune onefinestay’s operations in London before taking a leap of faith

and launching in New York. He explained, “We made a lot of mistakes

in London. It was expensive, but we built the tools, systems, best

practices, processes, and organization structures, so that when we’re

launching now, we’re coming into a market with far more

sophistication and a much more mature tool kit.” New York

homeowners warmed to the onefinestay concept relatively quickly,

joining at a rate that was three times as fast as when the company

launched in London. Marsh added, “It took us more than 14 months to

sign up our 100th homeowner in London. It’s taken only 6 months to

achieve that milestone in New York.”19 The same was true for

onefinestay’s Paris and Los Angeles markets, which took four and five

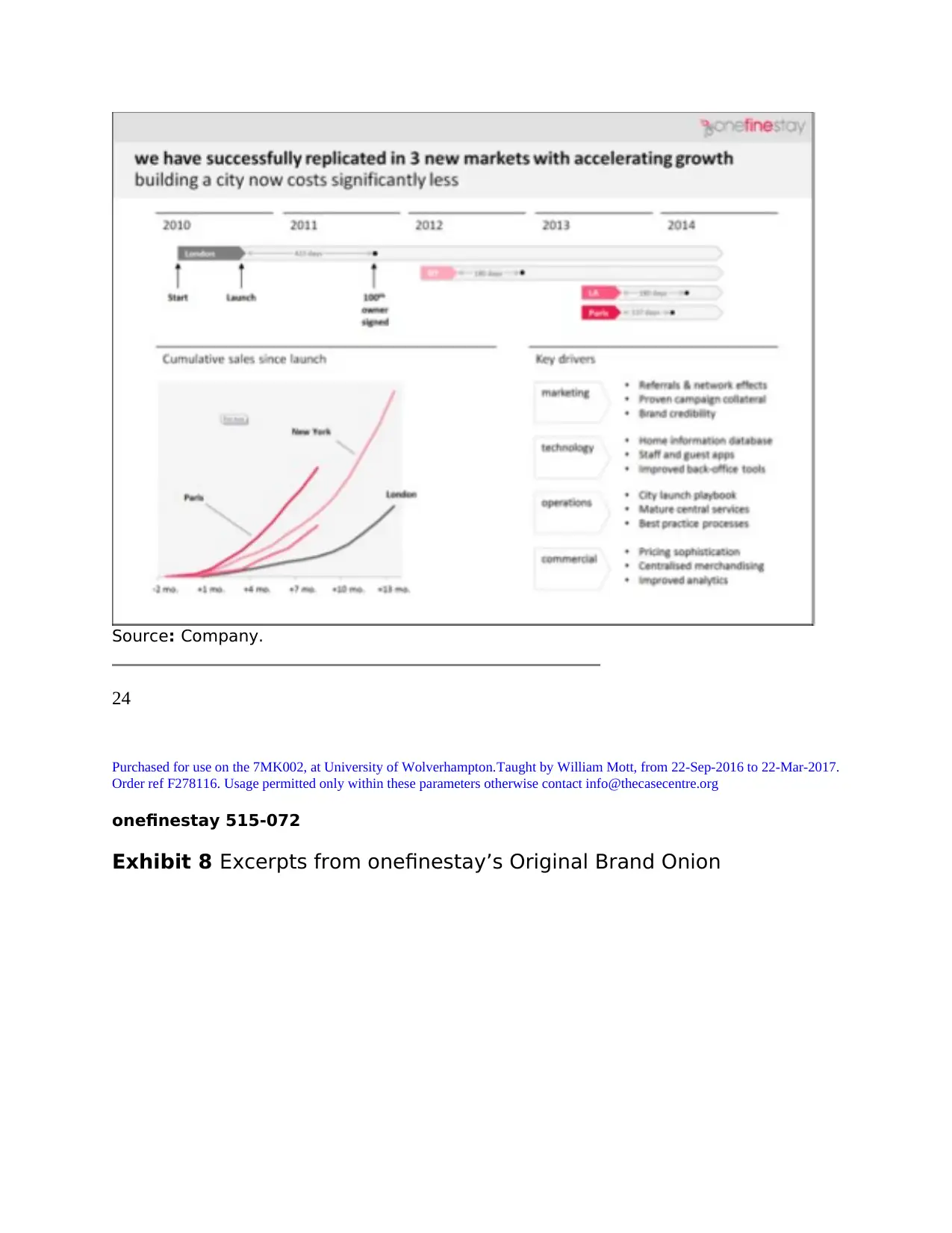

months, respectively, to sign 100 homeowners. (See Exhibit 7 for

additional data on new market growth.) Ultimately, Marsh hoped to

have operations in every major world city.

Marsh felt there were two key learnings the company had gleaned

from its expansion efforts to date. The first was the importance of

referrals and increased brand awareness. He elaborated,

"When we are launching into a new market and starting the city

operation, the first thing we do is to email our existing community and

It’s the antithesis of a transactional purchase: big ticket vacation travel

is a deliberative, considered, consultative purchase which will take

days or even weeks to consummate. Our typical guest or guest group

will visit our site many, many times, from multiple devices, before

making a final decision. That’s why we have a fully staffed follow-the-

sun inbound sales organization: at this price point and service level,

some people want support if only to provide comfort that we’re the

‘real deal’. A complex purchase path in a novel category makes it

especially difficult to get insight from traditional web analytics tools,

which are designed for simpler, more transactional small basket

commodity shopping. That in turn means determining the efficient

frontier for paid search acquisition, say, is quite a subtle and nuanced

analytical problem.

Expansion Plans

onefinestay’s launch in New York City was the first step in its broader

strategy of international expansion. Marsh’s plan was to test and fine-

tune onefinestay’s operations in London before taking a leap of faith

and launching in New York. He explained, “We made a lot of mistakes

in London. It was expensive, but we built the tools, systems, best

practices, processes, and organization structures, so that when we’re

launching now, we’re coming into a market with far more

sophistication and a much more mature tool kit.” New York

homeowners warmed to the onefinestay concept relatively quickly,

joining at a rate that was three times as fast as when the company

launched in London. Marsh added, “It took us more than 14 months to

sign up our 100th homeowner in London. It’s taken only 6 months to

achieve that milestone in New York.”19 The same was true for

onefinestay’s Paris and Los Angeles markets, which took four and five

months, respectively, to sign 100 homeowners. (See Exhibit 7 for

additional data on new market growth.) Ultimately, Marsh hoped to

have operations in every major world city.

Marsh felt there were two key learnings the company had gleaned

from its expansion efforts to date. The first was the importance of

referrals and increased brand awareness. He elaborated,

"When we are launching into a new market and starting the city

operation, the first thing we do is to email our existing community and

ask if they know folks who have a place in Paris or have their own

place in Paris, and many of them do. Our first 25 or 30 homes in Paris

were all through our own network.” Second, Marsh also recognized the

need for strong general managers to run the local markets. He

elaborated:

One of the constraints in growing this business is the management

competence needed to operate these business units. They are

commercially and operationally complex. You need a certain amount of

personal maturity because you’re often interacting with high net worth

homeowners and guests who have high expectations. You need to

pacify those on both ends, and deal quickly and effectively in service

recovery situations in a competent way, often without support or

recourse from the center of the business.

Increasingly, we’re convinced that we need to grow much of that

general management capability internally because it’s too unusual a

set of combination of skills and abilities. As a result, one real constraint

on the rates and locations of the launch strategy is our ability to find

the type of folks who are going to be effective at running these

businesses.

Once a general manager was in place for a new market, they typically

had two lieutenants—an operations lead and a commercial lead. The

commercial lead focused on the supply side, building the portfolio and

inventory of homes. The operations lead was initially responsible for

procuring a warehouse and office space, and then transitioned into the

day-to-day management and execution of the business. About nine

months after its launch, onefinestay’s Paris operation employed

approximately 25 people. Roughly one-third of the Paris employees

were on the commercial side, assisting with pricing analytics,

merchandising, sales, and account management of the portfolio. The

other two-thirds in the operations group were split roughly equally into

three functional areas. The member services team supported the guest

experience. The coordination and logistics team did the operational

planning to manage the different cleaning and staging groups. The

third team provided logistics and warehousing support.

Marsh was proud of the company’s expansion plans to date, and eager

to grow further quickly. On the one hand, Marsh recognized the value

of having a global footprint. As a budding hospitality brand, he wanted

place in Paris, and many of them do. Our first 25 or 30 homes in Paris

were all through our own network.” Second, Marsh also recognized the

need for strong general managers to run the local markets. He

elaborated:

One of the constraints in growing this business is the management

competence needed to operate these business units. They are

commercially and operationally complex. You need a certain amount of

personal maturity because you’re often interacting with high net worth

homeowners and guests who have high expectations. You need to

pacify those on both ends, and deal quickly and effectively in service

recovery situations in a competent way, often without support or

recourse from the center of the business.

Increasingly, we’re convinced that we need to grow much of that

general management capability internally because it’s too unusual a

set of combination of skills and abilities. As a result, one real constraint

on the rates and locations of the launch strategy is our ability to find

the type of folks who are going to be effective at running these

businesses.

Once a general manager was in place for a new market, they typically

had two lieutenants—an operations lead and a commercial lead. The

commercial lead focused on the supply side, building the portfolio and

inventory of homes. The operations lead was initially responsible for

procuring a warehouse and office space, and then transitioned into the

day-to-day management and execution of the business. About nine

months after its launch, onefinestay’s Paris operation employed

approximately 25 people. Roughly one-third of the Paris employees

were on the commercial side, assisting with pricing analytics,

merchandising, sales, and account management of the portfolio. The

other two-thirds in the operations group were split roughly equally into

three functional areas. The member services team supported the guest

experience. The coordination and logistics team did the operational

planning to manage the different cleaning and staging groups. The

third team provided logistics and warehousing support.

Marsh was proud of the company’s expansion plans to date, and eager

to grow further quickly. On the one hand, Marsh recognized the value

of having a global footprint. As a budding hospitality brand, he wanted

to be present in every key market to which his customers had occasion

to travel. One option was to add ten new cities around the world to the

onefinestay footprint by 2018.

Marsh commented, “As we add new markets, the customer acquisition

costs decline and lifetime value increases. The other compelling reason

to expand into new markets has to do with brand. Until we’re in

significantly more markets, travelers can’t always use our product. In

my view, this is a prerequisite to being able to get return on

investment from above-the-line marketing and advertising spend. It's

also clearly a necessary precondition to building a billion dollar

business.” However, adding additional cities to the onefinestay

network was costly from a marketing and operations standpoint. It

would take time and a significant amount of resources to expand this

way. Marsh worried that rapid expansion could stretch the fledgling

company’s human and financial resources and risk the company's

reputation and Net Promoter Scores. Variation in product and services

across markets could dilute the budding brand image he had built.

A second option was to increase onefinestay’s market penetration in

London, New York, Paris and Los Angeles. The company could leverage

the fixed marketing and operations costs they had already incurred by

further delving into the markets in which they had already established

a presence. Adding properties in these cities could help the company

strengthen its brand equity in four of the leading travel markets in the

world. The company was already the recipient of strong word-of-mouth

referrals from its existing homeowner hosts. It would be relatively easy

to find new homeowners to increase its supply of homes in these cities.

But, this option left most customers attracted to onefinestay’s online

presence unable to use the company’s services for most of their travel

needs.

Branding and Positioning Challenges

Marsh felt that the onefinestay brand had been cobbled together

without much deliberate attention during the company’s early years of

rapid growth. Initially, in 2009, he organized a marketing exercise with

a friend who had been a brand strategist and copywriter at a London

agency. March reflected:

We did a brand onion exerciseb, where my friend facilitated the

to travel. One option was to add ten new cities around the world to the

onefinestay footprint by 2018.

Marsh commented, “As we add new markets, the customer acquisition

costs decline and lifetime value increases. The other compelling reason

to expand into new markets has to do with brand. Until we’re in

significantly more markets, travelers can’t always use our product. In

my view, this is a prerequisite to being able to get return on

investment from above-the-line marketing and advertising spend. It's

also clearly a necessary precondition to building a billion dollar

business.” However, adding additional cities to the onefinestay

network was costly from a marketing and operations standpoint. It

would take time and a significant amount of resources to expand this

way. Marsh worried that rapid expansion could stretch the fledgling

company’s human and financial resources and risk the company's

reputation and Net Promoter Scores. Variation in product and services

across markets could dilute the budding brand image he had built.

A second option was to increase onefinestay’s market penetration in

London, New York, Paris and Los Angeles. The company could leverage

the fixed marketing and operations costs they had already incurred by

further delving into the markets in which they had already established

a presence. Adding properties in these cities could help the company

strengthen its brand equity in four of the leading travel markets in the

world. The company was already the recipient of strong word-of-mouth

referrals from its existing homeowner hosts. It would be relatively easy

to find new homeowners to increase its supply of homes in these cities.

But, this option left most customers attracted to onefinestay’s online

presence unable to use the company’s services for most of their travel

needs.

Branding and Positioning Challenges

Marsh felt that the onefinestay brand had been cobbled together

without much deliberate attention during the company’s early years of

rapid growth. Initially, in 2009, he organized a marketing exercise with

a friend who had been a brand strategist and copywriter at a London

agency. March reflected:

We did a brand onion exerciseb, where my friend facilitated the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

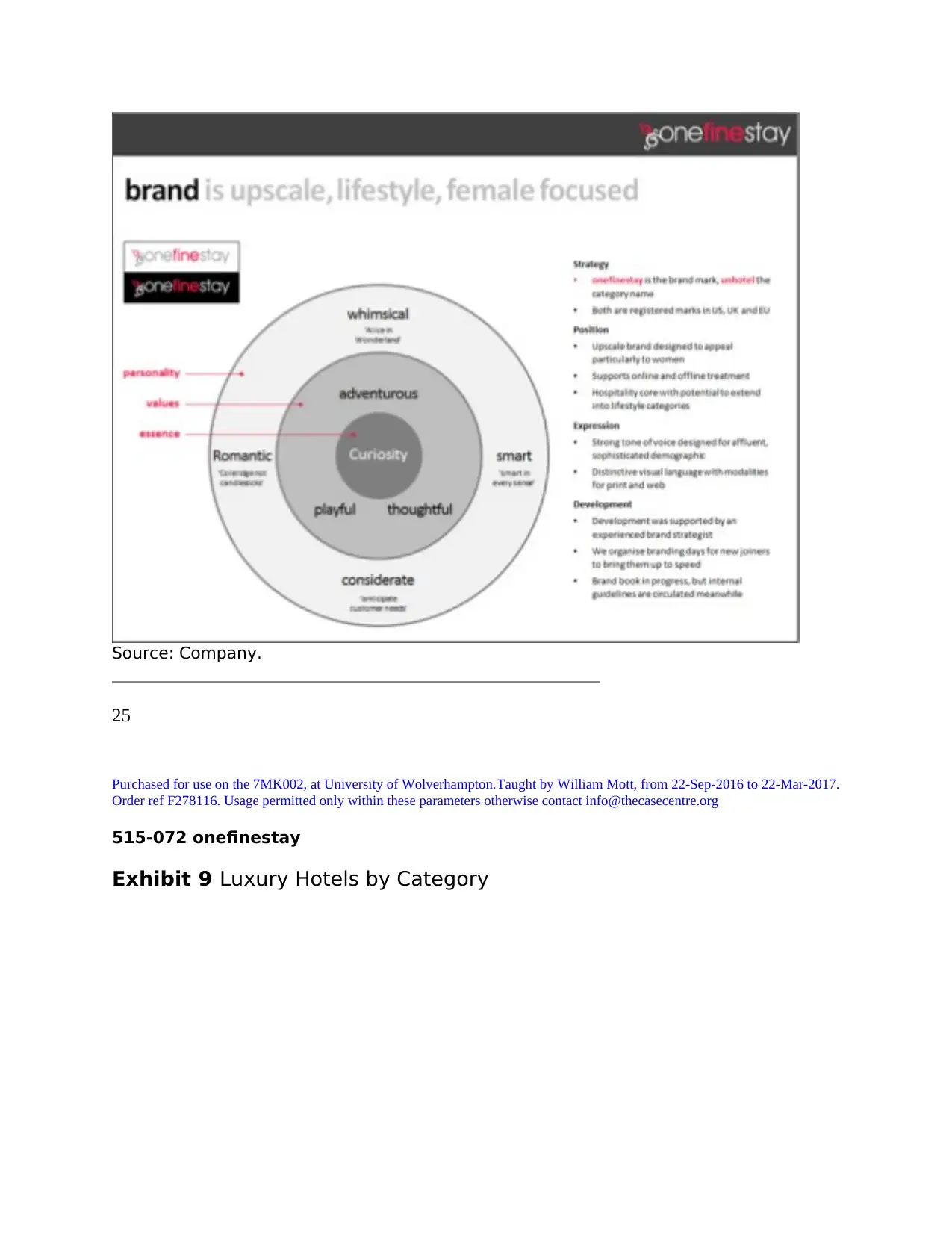

conversation, and we used whiteboards and brainstormed using word

associations and so on. We talked a lot about whether we should price

against hotels or vacation rentals. We talked about our “unhotel”

moniker and reinventing hospitality. At the end of it all, during the ‘ta-

da, this is the brand strategy presentation,’ I thought, ‘You sly dog.’ It

was very clever of him. He was doing group therapy and telling us our

personalities. He framed it very beautifully around an onion. The

middle of the onion was curiosity—the animating essence of the brand.

Around that, as layers, were behaviors: playful, adventurous and

considerate. Then, around the behaviors were personality traits—

smart, thoughtful, whimsical, and Romantic with a capital “R,” as in

Romantic poets, Romantic fiction, and Romance as an aesthetic ideal.

It was essentially about the people, not what the company was going

to do. We could have had exactly the same brand identity—maybe a

different name because the name implies something about the line of

service—but been in a different business. What’s fascinating is that

actually, if you’re talking about building a service brand, it’s the

behavior of the team that matters. And in a start-up, that means it’s

really about the personalities of the founders.

Marsh believed that the brand onion (see Exhibit 8 for excerpt) served

as a helpful starting point for the company, and that the focus on

behaviors continued to be useful as the company scaled and hired

additional employees. He and his co-founders sourced the onefinestay

logo for $200 through 99designs, an online graphic design firm. The

“unhotel” tag line they came up with also stuck.

By early 2014, Marsh was eager to revisit onefinestay’s branding

strategy and brought Cresswell on board to help. She reflected, “Fast-

forward a few years in a rapidly scaling business, and what you find is

that there may have been a certain amount of drift. In some areas, the

company is still thinking in a way that’s entirely consistent with the

way it had originally. In other areas, through a combination of factors,

the company is now speaking about itself in a different way. The bigger

mystery is, are any of those ways actually resonating with our guests

and our hosts and our staff?” Prior to joining onefinestay as director of

brand marketing, Cresswell ran global digital brand strategy at Ralph

Lauren Corporation. Cresswell’s work for onefinestay included a

branding project with three components: 1) gathering customer

insights, 2) creating an aspirational or mission statement, and 3)

associations and so on. We talked a lot about whether we should price

against hotels or vacation rentals. We talked about our “unhotel”

moniker and reinventing hospitality. At the end of it all, during the ‘ta-

da, this is the brand strategy presentation,’ I thought, ‘You sly dog.’ It

was very clever of him. He was doing group therapy and telling us our

personalities. He framed it very beautifully around an onion. The

middle of the onion was curiosity—the animating essence of the brand.

Around that, as layers, were behaviors: playful, adventurous and

considerate. Then, around the behaviors were personality traits—

smart, thoughtful, whimsical, and Romantic with a capital “R,” as in

Romantic poets, Romantic fiction, and Romance as an aesthetic ideal.

It was essentially about the people, not what the company was going

to do. We could have had exactly the same brand identity—maybe a

different name because the name implies something about the line of

service—but been in a different business. What’s fascinating is that

actually, if you’re talking about building a service brand, it’s the

behavior of the team that matters. And in a start-up, that means it’s

really about the personalities of the founders.

Marsh believed that the brand onion (see Exhibit 8 for excerpt) served

as a helpful starting point for the company, and that the focus on

behaviors continued to be useful as the company scaled and hired

additional employees. He and his co-founders sourced the onefinestay

logo for $200 through 99designs, an online graphic design firm. The

“unhotel” tag line they came up with also stuck.

By early 2014, Marsh was eager to revisit onefinestay’s branding

strategy and brought Cresswell on board to help. She reflected, “Fast-

forward a few years in a rapidly scaling business, and what you find is

that there may have been a certain amount of drift. In some areas, the

company is still thinking in a way that’s entirely consistent with the

way it had originally. In other areas, through a combination of factors,

the company is now speaking about itself in a different way. The bigger

mystery is, are any of those ways actually resonating with our guests

and our hosts and our staff?” Prior to joining onefinestay as director of

brand marketing, Cresswell ran global digital brand strategy at Ralph

Lauren Corporation. Cresswell’s work for onefinestay included a

branding project with three components: 1) gathering customer

insights, 2) creating an aspirational or mission statement, and 3)

developing a new set of creative briefs. Cresswell elaborated, “What

may have started as a quest for a refreshed color scheme and a little

bit more consistency in some of the language we use is evolving into

the opportunity for something a little bigger. Ultimately the color,

typography, or logo doesn’t really matter. What matters is if you have

a shared sense of purpose as a team that informs all of your behaviors

and all of the ways in which you present yourself to the customer. And,

that those ways are meaningfully important to the customer.”

During the spring and summer of 2014, Creswell and her team

analyzed dozens of detailed interviews with onefinestay guests and

hosts. Cresswell noted that "when you read the 40 hours of transcripts,

you realize you have this amazing story telling—guests telling what it

means to travel and hosts telling what it means to open up your home

to someone else. We tend to talk a lot about features, but not as much

about the benefits that are emotional. The most successful brands I

see are the ones that actually figure out how to turn all their features

and emotional benefits into something that truly touches their

customers.” In thinking about branding strategy, Cresswell focused on

onefinestay's unique points of difference and how they would help

drive growth over the next few years.

As she thought about onefinestay's ‘unhotel’ moniker, she wondered

whether positioning the company versus traditional hospitality options

was the right strategy or whether she should consider changing the

positioning to communicate what the company stood for, rather than

what it stood against. Marsh explained, “We feel like we are

reinventing hospitality, but what the heck do we call this new

category? I had read works by the marketing professionals, Al Ries and

Jack Trout and was thinking of ‘the uncola’ launch campaign for 7-up.

Can you define something by what it isn’t and what are the pros and

cons of doing that? People have very polarizing reactions to the

‘unhotel.’ Some people love it and others absolutely hate it.”

Market Segmentation

As a result of the research, in July 2014, on its Web site, onefinestay

clustered its home listings into four consumer-use groupings—family,

prestige, explore, and work—as a way for travelers to search more

efficiently for properties that would meet their needs. Creswell

explained:

may have started as a quest for a refreshed color scheme and a little

bit more consistency in some of the language we use is evolving into

the opportunity for something a little bigger. Ultimately the color,

typography, or logo doesn’t really matter. What matters is if you have

a shared sense of purpose as a team that informs all of your behaviors

and all of the ways in which you present yourself to the customer. And,

that those ways are meaningfully important to the customer.”

During the spring and summer of 2014, Creswell and her team

analyzed dozens of detailed interviews with onefinestay guests and

hosts. Cresswell noted that "when you read the 40 hours of transcripts,

you realize you have this amazing story telling—guests telling what it

means to travel and hosts telling what it means to open up your home

to someone else. We tend to talk a lot about features, but not as much

about the benefits that are emotional. The most successful brands I

see are the ones that actually figure out how to turn all their features

and emotional benefits into something that truly touches their

customers.” In thinking about branding strategy, Cresswell focused on

onefinestay's unique points of difference and how they would help

drive growth over the next few years.

As she thought about onefinestay's ‘unhotel’ moniker, she wondered

whether positioning the company versus traditional hospitality options

was the right strategy or whether she should consider changing the

positioning to communicate what the company stood for, rather than

what it stood against. Marsh explained, “We feel like we are

reinventing hospitality, but what the heck do we call this new

category? I had read works by the marketing professionals, Al Ries and

Jack Trout and was thinking of ‘the uncola’ launch campaign for 7-up.

Can you define something by what it isn’t and what are the pros and

cons of doing that? People have very polarizing reactions to the

‘unhotel.’ Some people love it and others absolutely hate it.”

Market Segmentation

As a result of the research, in July 2014, on its Web site, onefinestay

clustered its home listings into four consumer-use groupings—family,

prestige, explore, and work—as a way for travelers to search more

efficiently for properties that would meet their needs. Creswell

explained:

The early work was an attempt to get to know our people better and to

try to group them into categories by need. A number of segments

emerged around use cases and we thought we’d test with something

very quick and dirty to see whether they’d hold. It was basically just an

onsite merchandizing play.

What you see [on the Web site] are actually not so much segments as

they are use cases. Two are based on needs, depending on the nature

of the travel—work or family. If I am a business traveler, I might only

need an apartment or a small home in a certain location. On the other

hand, lots of people mix work and business travel all the time. We

know that it is really compelling to choose a private home instead of a

hotel so that your wife and kids can come and stay at the end of the

trip.

The other two folios are based more on risk versus cost. The prestige

folio is for people who want to invest a little bit more to make the

experience of staying in a private home as close to a hotel as you can

get—informally what we call de-risking. With a prestige home, you will

get a very high spec kitchen and bath. They will be pretty luxurious in

terms of the fixtures and fittings, and you won’t have some of the

colorful quirks that can come along with staying in a private home and

that some people really enjoy. At the other end of the spectrum is the

explorer folio. Some people have a lot more flexibility with

neighborhood. If you want, you can get a very big home, slightly

further away from the town center that will allow you to travel at a

very economical rate, particularly if you start to think about it on a per

room basis.

We hoped people would have an easier job navigating the site, and are

noticing that people are starting to use the groupings as a new way to

choose a home. Since we added the groupings, travelers who find us

through search engine marketing have had a much higher conversion

rate. The customer folios are still a pretty blunt instrument, and the

decision to use them was very much in the spirit of, ‘Hey we learned

something, let’s develop a hypothesis.’ At the same time, it may not be

enough to make a list of homes that seem to fit one set of needs better

than another. We may have to add and maintain a unique service

envelope for homes in each of the four categories. There are a bunch

of reasons that stop business travelers from renting a private home