Effectiveness of CBT and Task-Oriented Balance Training in Reducing Fear of Falling in Chronic Stroke Patients

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/20

|10

|8960

|76

AI Summary

This study protocol aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and task-oriented balance training (TOBT) in reducing the fear of falling in patients with chronic stroke. The study will be a randomized controlled trial with a placebo-controlled single-blind parallel-group design. The primary outcome measure is subjective balance confidence, and the secondary outcome measures include fear-avoidance behavior, balance ability, fall risk, level of activities of daily living, community reintegration, and health-related quality of life. The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the registration number NCT02937532.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access

Effectiveness of a combination of cognitive

behavioraltherapy and task-oriented

balance training in reducing the fear of

falling in patients with chronic stroke:study

protocolfor a randomized controlled trial

Tai-Wa Liu1,2

, GabrielY.F.Ng1 and Shamay S.M.Ng1*

Abstract

Background:The consequences offalls are devastating forpatients with stroke.Balance problems and fearof

falling are two majorchallenges,and recentsystematic reviews have revealed thathabitualphysicalexercise

training alone cannot reduce the occurrence of falls in stroke survivors.However,recent trials with community-dwelling

healthy older adults yielded the promising result that interventions with a cognitive behavioral therapy (CB

can simultaneously promote balance and reduce the fear of falling.Therefore,the aim of the proposed clinical trial is to

evaluate the effectiveness of a combination of CBT and task-oriented balance training (TOBT) in promoting

balance confidence,and thereby reducing fear-avoidance behavior,improving balance ability,reducing fall risk,and

promoting independent living,community reintegration,and health-related quality of life of patients with stroke.

Methods: The study will constitute a placebo-controlled single-blind parallel-group randomized controlled t

patients are assessed immediately,at 3 months,and at 12 months.The selected participants will be randomly allocated

into one of two parallel groups (the experimental group and the control group) with a 1:1 ratio.Both groups will receive

45 min of TOBT twice per week for 8 weeks.In addition,the experimental group will receive a 45-min CBT-based group

intervention,and the control group will receive 45 min of general health education (GHE) twice per week for 8

The primary outcome measure is subjective balance confidence.The secondary outcome measures are fear-avoidance

behavior,balance ability,fall risk,level of activities of daily living,community reintegration,and health-related quality of

life.

Discussion: The proposed clinical trial will compare the effectiveness of CBT combined with TOBT and GHE

with TOBT in promoting subjective balance confidence among chronic stroke patients.

We hope our results will provide evidence of a safe,cost-effective,and readily transferrable therapeutic approach to

clinical practice that reduces fear-avoidance behavior,improves balance ability,reduces fall risk,promotes independence

and community reintegration,and enhances health-related quality of life.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov,NCT02937532.Registered on 17 October 2016.

Keywords: Stroke rehabilitation,Cognitive behavioral therapy,Fear of falling,Subjective balance confidence,Balance self-

efficacy,Fall risk

* Correspondence:Shamay.Ng@polyu.edu.hk

1Department of Rehabilitation Sciences,The Hong Kong Polytechnic

University,Hung Hom,Hong Kong,SpecialAdministrative Region of China

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2549-z

Effectiveness of a combination of cognitive

behavioraltherapy and task-oriented

balance training in reducing the fear of

falling in patients with chronic stroke:study

protocolfor a randomized controlled trial

Tai-Wa Liu1,2

, GabrielY.F.Ng1 and Shamay S.M.Ng1*

Abstract

Background:The consequences offalls are devastating forpatients with stroke.Balance problems and fearof

falling are two majorchallenges,and recentsystematic reviews have revealed thathabitualphysicalexercise

training alone cannot reduce the occurrence of falls in stroke survivors.However,recent trials with community-dwelling

healthy older adults yielded the promising result that interventions with a cognitive behavioral therapy (CB

can simultaneously promote balance and reduce the fear of falling.Therefore,the aim of the proposed clinical trial is to

evaluate the effectiveness of a combination of CBT and task-oriented balance training (TOBT) in promoting

balance confidence,and thereby reducing fear-avoidance behavior,improving balance ability,reducing fall risk,and

promoting independent living,community reintegration,and health-related quality of life of patients with stroke.

Methods: The study will constitute a placebo-controlled single-blind parallel-group randomized controlled t

patients are assessed immediately,at 3 months,and at 12 months.The selected participants will be randomly allocated

into one of two parallel groups (the experimental group and the control group) with a 1:1 ratio.Both groups will receive

45 min of TOBT twice per week for 8 weeks.In addition,the experimental group will receive a 45-min CBT-based group

intervention,and the control group will receive 45 min of general health education (GHE) twice per week for 8

The primary outcome measure is subjective balance confidence.The secondary outcome measures are fear-avoidance

behavior,balance ability,fall risk,level of activities of daily living,community reintegration,and health-related quality of

life.

Discussion: The proposed clinical trial will compare the effectiveness of CBT combined with TOBT and GHE

with TOBT in promoting subjective balance confidence among chronic stroke patients.

We hope our results will provide evidence of a safe,cost-effective,and readily transferrable therapeutic approach to

clinical practice that reduces fear-avoidance behavior,improves balance ability,reduces fall risk,promotes independence

and community reintegration,and enhances health-related quality of life.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov,NCT02937532.Registered on 17 October 2016.

Keywords: Stroke rehabilitation,Cognitive behavioral therapy,Fear of falling,Subjective balance confidence,Balance self-

efficacy,Fall risk

* Correspondence:Shamay.Ng@polyu.edu.hk

1Department of Rehabilitation Sciences,The Hong Kong Polytechnic

University,Hung Hom,Hong Kong,SpecialAdministrative Region of China

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2549-z

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Background

Fear offalling (FoF)is one ofthe mostcommon post-

stroke complications,and is widely acknowledged as part

of a vicious circle [1] leading to actual falls [2].It is a de-

bilitating post-fallsyndrome stemming from low balance

self-efficacy and the fearfulanticipation offalling [3,4].

The reported prevalenceof FoF variesbetween post-

stroke stages,ranging from 54% before discharge [5] from

an acute unit to 44% at 6 months after stroke [6] and 58%

among community-dwelling patients with stroke [7].If no

action is taken, FoF spirals into a loss of physical function,

dependency on others for assistance with activities of daily

living (ADL),restrictionson daily activities[4], and a

higher fallrate,[8] eventually compromising community

integration [9].

Two recent systematic reviews synthesized the findings

of interventions targeting FoF.Bula et al.’s [10] review of

46 randomizedcontrolledtrials (RCTs) with 6794

community-dwelling elderly persons revealed that the ma-

jority of the reviewed studies (n = 38) focused on fall pre-

vention and balance improvement,with FoF regarded as a

secondary outcome.In the eight studies directly address-

ing the fear offearing,the use of physiologicalinterven-

tions such astai chi [11];strengthening,balance and

walking exercises [12]; psychological interventions such as

cognitive behavioraltherapy (CBT)[13,14];and guided

relaxation and exercise imagery [15] was reported to help

reduce FoF among community-dwelling older people.

In another systematic review, Tang et al.[16] examined

19 clinical trials addressingFoF among peoplewith

stroke.Despiteits significantinfluenceon strokere-

habilitation,FoF was regarded only as a secondary target

in the studies reviewed.Tang’s [16] meta-analysis of15

clinicaltrials with 627 participants revealed thatinten-

sive exercise-based physiologicalinterventions,such as

gait training [17–20],exergaming [21],yoga [22],and a

combination of fitness,mobility and functionalexercises

[23,24],can reduce FoF with a medium effect size (stan-

dardized mean difference 0.44;95% confidence interval

(0.11–0.77);p = 0.009).No improvements were noted in

the four reviewed studies using psychologicalinterven-

tions (motor imagery)[25–28],and no retention effect

was noted in the studies with a follow-up assessment.

However,the effectivenessof CBT as a psychological

intervention in reducing the FoF ofstroke patients has

not been examined.

CBT is a psychotherapeuticapproach thatredirects

negative cognitive,emotional,or behavioralresponses to

help people developcoping mechanismsand self-

confidence [29].For example,people with FoF originating

from impaired balanceself-efficacycan use CBT to

change their self-defeating beliefs,improve their balance

self-efficacy and replace theirunrealistic anticipation of

falls and magnified FoF consequenceswith a realistic,

positive perspective on falls,in turn reducing their fear

avoidance.

As summarized by Bula etal. [10] and Tang etal.

[16],studies have shown that physicalexercise can re-

duce FoF in older people and people with stroke as

either a primary or a secondary outcome.As psycho-

logicalinterventionsoffer anotherpossible meansof

reducing FoF,we aim to examine the effectiveness of

a combinationof CBT and task-orientedbalance

training (TOBT)in reducing the FoF ofpeople with

stroke.TOBT will be used in the proposed study be-

causeit targetsstroke-specificimpairmentsand has

been clinicallyproven to improvethe balanceper-

formance ofpeople with stroke [30,31]. The inclu-

sion of CBT in our treatmentarm is based on our

hypothesis thatCBT is an adjuncttherapy capable of

optimizing the treatmenteffectsof exercise in redu-

cing FoF.It is expected to tackle FoF directly through

the promotion ofbalance self-efficacy,and its indirect

effectswill be mediated by repeated exercise and re-

duced fear-avoidance behavior,further enhancing bal-

ance performanceand ADL, and therebyimproving

community integration.The combined effects ofCBT

and TOBT in reducing FoF are expected to improve

patients’balance,reduce their risk offalling,increase

their independence,and thereby promote theircom-

munity integration.Indeed,in Huang et al.’s[32] re-

centRCT with elderly persons,CBT with an exercise

intervention (n = 27)performed betterthan either

CBT alone (n = 27)or treatmentas usual(n = 26)in

reducing FoF and depression and enhancing mobility

and muscle strength,with retention effectsobserved

up to 5 monthslater.Therefore,the proposed study

aims to determinewhether combiningCBT with

TOBT augments the latter’s positive treatmenteffects

on FoF, and thus fear-avoidancebehavior,balance

ability,fall risk, independentliving, enhancing com-

munityintegration,and health-related qualityof life

among community-dwelling seniors with stroke.

To develop an intervention for clinical use, a protocol is

necessary to ensure the consistency ofimplementation

and ease ofreplication.Therefore,the objective ofthis

paper is to report the details of a protocolfor combining

CBT and TOBT to reduce FoF among people with stroke.

Methods

Trial design

The proposedstudy will be a placebo-controlled

single-blindparallel-groupRCT with a 12-month

follow-up, conducted with community-dwelling

chronic stroke survivorswith FoF at a university-

based rehabilitation center.The findingsof the trial

will be reported in accordance with the Consolidated

Standards ofReporting Statement [33].

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 2 of 10

Fear offalling (FoF)is one ofthe mostcommon post-

stroke complications,and is widely acknowledged as part

of a vicious circle [1] leading to actual falls [2].It is a de-

bilitating post-fallsyndrome stemming from low balance

self-efficacy and the fearfulanticipation offalling [3,4].

The reported prevalenceof FoF variesbetween post-

stroke stages,ranging from 54% before discharge [5] from

an acute unit to 44% at 6 months after stroke [6] and 58%

among community-dwelling patients with stroke [7].If no

action is taken, FoF spirals into a loss of physical function,

dependency on others for assistance with activities of daily

living (ADL),restrictionson daily activities[4], and a

higher fallrate,[8] eventually compromising community

integration [9].

Two recent systematic reviews synthesized the findings

of interventions targeting FoF.Bula et al.’s [10] review of

46 randomizedcontrolledtrials (RCTs) with 6794

community-dwelling elderly persons revealed that the ma-

jority of the reviewed studies (n = 38) focused on fall pre-

vention and balance improvement,with FoF regarded as a

secondary outcome.In the eight studies directly address-

ing the fear offearing,the use of physiologicalinterven-

tions such astai chi [11];strengthening,balance and

walking exercises [12]; psychological interventions such as

cognitive behavioraltherapy (CBT)[13,14];and guided

relaxation and exercise imagery [15] was reported to help

reduce FoF among community-dwelling older people.

In another systematic review, Tang et al.[16] examined

19 clinical trials addressingFoF among peoplewith

stroke.Despiteits significantinfluenceon strokere-

habilitation,FoF was regarded only as a secondary target

in the studies reviewed.Tang’s [16] meta-analysis of15

clinicaltrials with 627 participants revealed thatinten-

sive exercise-based physiologicalinterventions,such as

gait training [17–20],exergaming [21],yoga [22],and a

combination of fitness,mobility and functionalexercises

[23,24],can reduce FoF with a medium effect size (stan-

dardized mean difference 0.44;95% confidence interval

(0.11–0.77);p = 0.009).No improvements were noted in

the four reviewed studies using psychologicalinterven-

tions (motor imagery)[25–28],and no retention effect

was noted in the studies with a follow-up assessment.

However,the effectivenessof CBT as a psychological

intervention in reducing the FoF ofstroke patients has

not been examined.

CBT is a psychotherapeuticapproach thatredirects

negative cognitive,emotional,or behavioralresponses to

help people developcoping mechanismsand self-

confidence [29].For example,people with FoF originating

from impaired balanceself-efficacycan use CBT to

change their self-defeating beliefs,improve their balance

self-efficacy and replace theirunrealistic anticipation of

falls and magnified FoF consequenceswith a realistic,

positive perspective on falls,in turn reducing their fear

avoidance.

As summarized by Bula etal. [10] and Tang etal.

[16],studies have shown that physicalexercise can re-

duce FoF in older people and people with stroke as

either a primary or a secondary outcome.As psycho-

logicalinterventionsoffer anotherpossible meansof

reducing FoF,we aim to examine the effectiveness of

a combinationof CBT and task-orientedbalance

training (TOBT)in reducing the FoF ofpeople with

stroke.TOBT will be used in the proposed study be-

causeit targetsstroke-specificimpairmentsand has

been clinicallyproven to improvethe balanceper-

formance ofpeople with stroke [30,31]. The inclu-

sion of CBT in our treatmentarm is based on our

hypothesis thatCBT is an adjuncttherapy capable of

optimizing the treatmenteffectsof exercise in redu-

cing FoF.It is expected to tackle FoF directly through

the promotion ofbalance self-efficacy,and its indirect

effectswill be mediated by repeated exercise and re-

duced fear-avoidance behavior,further enhancing bal-

ance performanceand ADL, and therebyimproving

community integration.The combined effects ofCBT

and TOBT in reducing FoF are expected to improve

patients’balance,reduce their risk offalling,increase

their independence,and thereby promote theircom-

munity integration.Indeed,in Huang et al.’s[32] re-

centRCT with elderly persons,CBT with an exercise

intervention (n = 27)performed betterthan either

CBT alone (n = 27)or treatmentas usual(n = 26)in

reducing FoF and depression and enhancing mobility

and muscle strength,with retention effectsobserved

up to 5 monthslater.Therefore,the proposed study

aims to determinewhether combiningCBT with

TOBT augments the latter’s positive treatmenteffects

on FoF, and thus fear-avoidancebehavior,balance

ability,fall risk, independentliving, enhancing com-

munityintegration,and health-related qualityof life

among community-dwelling seniors with stroke.

To develop an intervention for clinical use, a protocol is

necessary to ensure the consistency ofimplementation

and ease ofreplication.Therefore,the objective ofthis

paper is to report the details of a protocolfor combining

CBT and TOBT to reduce FoF among people with stroke.

Methods

Trial design

The proposedstudy will be a placebo-controlled

single-blindparallel-groupRCT with a 12-month

follow-up, conducted with community-dwelling

chronic stroke survivorswith FoF at a university-

based rehabilitation center.The findingsof the trial

will be reported in accordance with the Consolidated

Standards ofReporting Statement [33].

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 2 of 10

Choice of comparator

A placebo control intervention,general health education

(GHE), will be provided for the controlgroup to help

measure the effects ofCBT alone.To rule out potential

placebo effectssuch asattention from therapistsand

knowledge oftreatmentconditions,the GHE program

will provide no information related to subjective balance

confidence,activity avoidance,falls,or physicalactivity,

but only information related to generalhealth issues

such as healthy food choices and foot care.

Null hypothesis

The null hypothesiswill be that the efficacy ofCBT

combined with TOBT does not differ significantly from

that of GHE combined with TOBT in promoting balance

self-efficacy,thus reducing fear-avoidance behavior,en-

hancing balance ability,reducing fall risk,and improving

community reintegration and health-related quality of

life for people with stroke.

Participants

Prospective participants willbe required to meet the fol-

lowing inclusion criteria:(i) aged between 55 and 85,(ii)

diagnosed with a first unilateral ischemic brain injury or in-

tracerebral hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging or

computed tomography within 1–6 years post-stroke,(iii)

discharged from all rehabilitation services at least 6 months

before the program,(iv) able to walk independently for at

least 10 m with or without an assistive device,(v) showing

low balance self-efficacy [scoring less than 80 on the Chin-

ese version ofthe Activities-specific Balance Confidence

(ABC-C) Scale] [34],(vi) scoring higher than 7 out of 10

on the Chinese version ofthe Abbreviated MentalTest

[35],and (vii) able to follow instructions and provide writ-

ten informed consent.

Individuals willbe excluded if they have any additional

medical,cardiovascular,orthopedic,psychiatric,or psy-

chological conditions that will hinder proper treatment or

assessment,if they presentwith receptive dysphasia or

significant lower limb peripheral neuropathy, or if they are

involved in drug studies or other clinical trials.

Therapists and research personnel

Two research assistants with at least 2 years ofresearch

experience in physicalexercise training willbe the asses-

sors of this study.They will be given a 1-day training ses-

sion on obtainingoutcome measurementsby an

experienced physiotherapist before the study. Training will

be provided in both the theory and practice of using the

outcome measures.All of the assessors willrehearse the

outcome measures with the research team personnelto

standardize the assessment.To establish the interrater re-

liability,the two assessors willrate five participants and

then review for discrepancies, if any.

The two TOBT therapists willhave been trained by an

experienced physiotherapistand have at least2 years of

post-qualification experience as therapists in physicalex-

ercise training.They willbe provided with written pro-

gression guidelines (Table 1).A regular review of training

records and spotobservations willbe conducted by the

experienced physiotherapist to enhance adherence to the

written progression guidelines. The CBT therapists will be

three psychiatric nurses who have qualified as cognitive

therapists.They will all have atleast5 yearsof post-

qualification experience with applying CBT clinically.A

treatment manualand materials have already been devel-

oped with reference to Tennstedt et al.’s [13] and Zijlstra

et al.’s [14] researchon FoF as experiencedby

community-dwelling olderadultsand reviewed by the

three certified cognitive therapists involved in the study.

To ensure treatment integrity,the CBT intervention has

already been piloted and audiotaped.Each CBT therapist

evaluated the pilotsessionsto assesstheir compliance

with the treatmentmanual,the achievementof session

goals,and the use of CBT techniques.The GHE interven-

tion willbe delivered by two research assistants notin-

volvedin the assessmentor any other part of the

Table 1 Progression criteria for task-oriented balance training

Exercise Progression criteria Method of progression

Stepping up

and down

Able to complete 50 times Starting with a 2-in.-high wooden step,then progressing

to 4- and 6-in.-high wooden steps after the progression

criteria have been met

Heel-raising

exercises

Able to complete 25 times with at least 5 s

held on each repetition

Starting with a 2-in.-high wooden step,then progressing to

4- and 6-in.-high wooden ramp after the progression criteria

have been met

Semi-

squatting

Able to maintain knee flexion angle of 30

degrees without obvious shaking

Starting with a 3-min rest intervalmidway through the trial,

which is subsequently reduced to 2 min,1 min,and 0 min

Standing on

duraDisc

Able to stand without external assistance for

at least 1 min (holding handrail or supported by another)

Decrease the base of support

Walking

across

obstacles

Able to complete the task within a pre-set

duration (20 s at the beginning) without knocking

down the obstacles

Shorten the pre-set duration and increase number

of obstacles

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 3 of 10

A placebo control intervention,general health education

(GHE), will be provided for the controlgroup to help

measure the effects ofCBT alone.To rule out potential

placebo effectssuch asattention from therapistsand

knowledge oftreatmentconditions,the GHE program

will provide no information related to subjective balance

confidence,activity avoidance,falls,or physicalactivity,

but only information related to generalhealth issues

such as healthy food choices and foot care.

Null hypothesis

The null hypothesiswill be that the efficacy ofCBT

combined with TOBT does not differ significantly from

that of GHE combined with TOBT in promoting balance

self-efficacy,thus reducing fear-avoidance behavior,en-

hancing balance ability,reducing fall risk,and improving

community reintegration and health-related quality of

life for people with stroke.

Participants

Prospective participants willbe required to meet the fol-

lowing inclusion criteria:(i) aged between 55 and 85,(ii)

diagnosed with a first unilateral ischemic brain injury or in-

tracerebral hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging or

computed tomography within 1–6 years post-stroke,(iii)

discharged from all rehabilitation services at least 6 months

before the program,(iv) able to walk independently for at

least 10 m with or without an assistive device,(v) showing

low balance self-efficacy [scoring less than 80 on the Chin-

ese version ofthe Activities-specific Balance Confidence

(ABC-C) Scale] [34],(vi) scoring higher than 7 out of 10

on the Chinese version ofthe Abbreviated MentalTest

[35],and (vii) able to follow instructions and provide writ-

ten informed consent.

Individuals willbe excluded if they have any additional

medical,cardiovascular,orthopedic,psychiatric,or psy-

chological conditions that will hinder proper treatment or

assessment,if they presentwith receptive dysphasia or

significant lower limb peripheral neuropathy, or if they are

involved in drug studies or other clinical trials.

Therapists and research personnel

Two research assistants with at least 2 years ofresearch

experience in physicalexercise training willbe the asses-

sors of this study.They will be given a 1-day training ses-

sion on obtainingoutcome measurementsby an

experienced physiotherapist before the study. Training will

be provided in both the theory and practice of using the

outcome measures.All of the assessors willrehearse the

outcome measures with the research team personnelto

standardize the assessment.To establish the interrater re-

liability,the two assessors willrate five participants and

then review for discrepancies, if any.

The two TOBT therapists willhave been trained by an

experienced physiotherapistand have at least2 years of

post-qualification experience as therapists in physicalex-

ercise training.They willbe provided with written pro-

gression guidelines (Table 1).A regular review of training

records and spotobservations willbe conducted by the

experienced physiotherapist to enhance adherence to the

written progression guidelines. The CBT therapists will be

three psychiatric nurses who have qualified as cognitive

therapists.They will all have atleast5 yearsof post-

qualification experience with applying CBT clinically.A

treatment manualand materials have already been devel-

oped with reference to Tennstedt et al.’s [13] and Zijlstra

et al.’s [14] researchon FoF as experiencedby

community-dwelling olderadultsand reviewed by the

three certified cognitive therapists involved in the study.

To ensure treatment integrity,the CBT intervention has

already been piloted and audiotaped.Each CBT therapist

evaluated the pilotsessionsto assesstheir compliance

with the treatmentmanual,the achievementof session

goals,and the use of CBT techniques.The GHE interven-

tion willbe delivered by two research assistants notin-

volvedin the assessmentor any other part of the

Table 1 Progression criteria for task-oriented balance training

Exercise Progression criteria Method of progression

Stepping up

and down

Able to complete 50 times Starting with a 2-in.-high wooden step,then progressing

to 4- and 6-in.-high wooden steps after the progression

criteria have been met

Heel-raising

exercises

Able to complete 25 times with at least 5 s

held on each repetition

Starting with a 2-in.-high wooden step,then progressing to

4- and 6-in.-high wooden ramp after the progression criteria

have been met

Semi-

squatting

Able to maintain knee flexion angle of 30

degrees without obvious shaking

Starting with a 3-min rest intervalmidway through the trial,

which is subsequently reduced to 2 min,1 min,and 0 min

Standing on

duraDisc

Able to stand without external assistance for

at least 1 min (holding handrail or supported by another)

Decrease the base of support

Walking

across

obstacles

Able to complete the task within a pre-set

duration (20 s at the beginning) without knocking

down the obstacles

Shorten the pre-set duration and increase number

of obstacles

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 3 of 10

intervention,using audio-visualaidsand materialsthat

have already been developed.

Procedure

Participantswill be recruited from a local self-help

group for people with stroke through poster advertise-

ments.On receiving telephone calls from interested par-

ties,our recruitment research assistantwill perform an

initial eligibilityscreening and offerappointmentsto

gain written informed consentand complete a baseline

assessment.

All of the potentialparticipants willmeet individually

in the study venue to enable the researchers to explain

the details of the study,such as its aims,benefits,risks,

and confidentiality,and then check the applicants’eligi-

bility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.If indi-

viduals are both interested in joining and eligible to join

the clinicaltrial,written informed consentwill be ob-

tainedbeforethe baselineassessmentis conducted.

Questionnaires relating to sociodemographic character-

istics,variables ofinterest,and physicaland functional

performance will be completed on the same day.

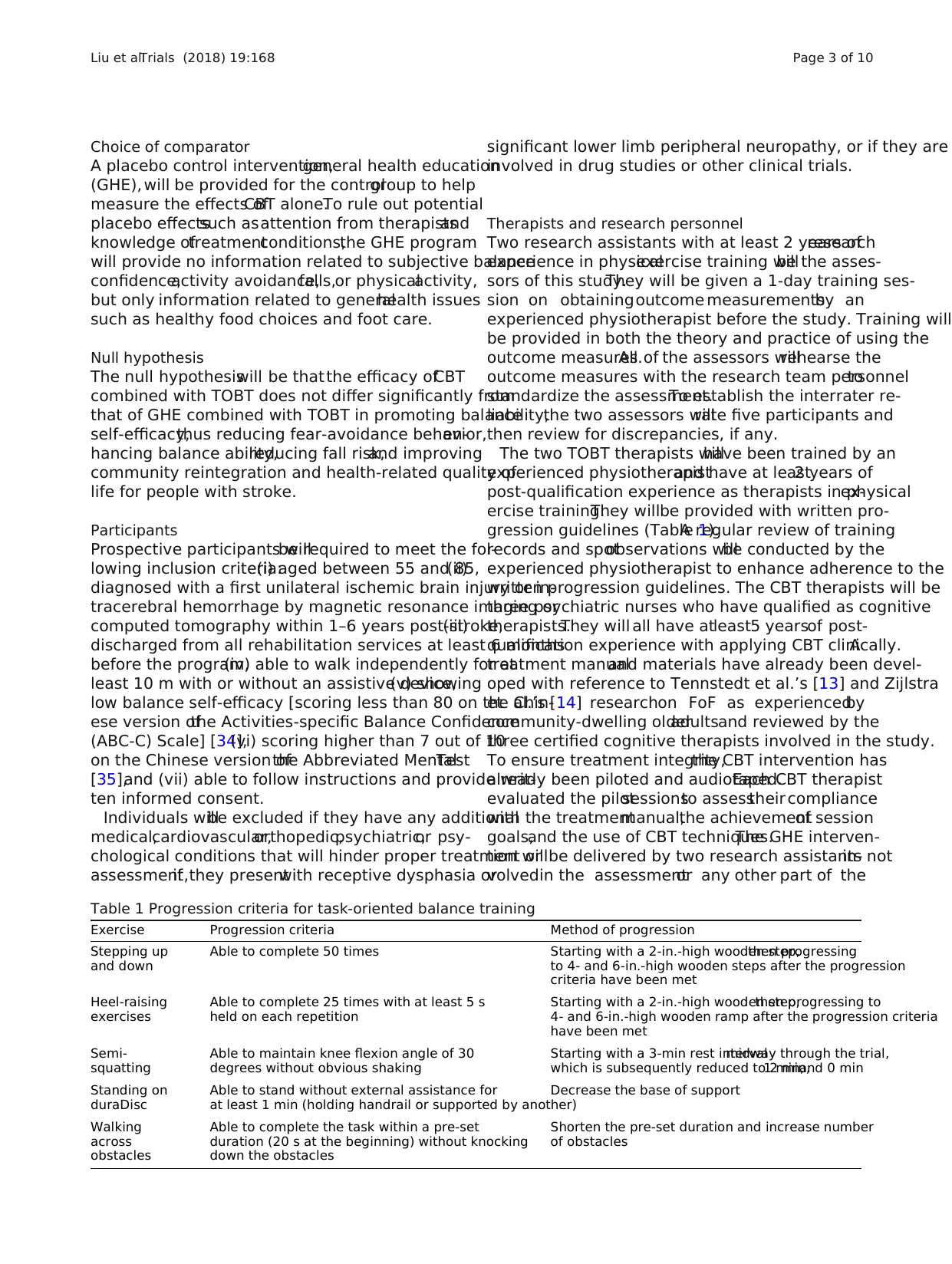

Measurements

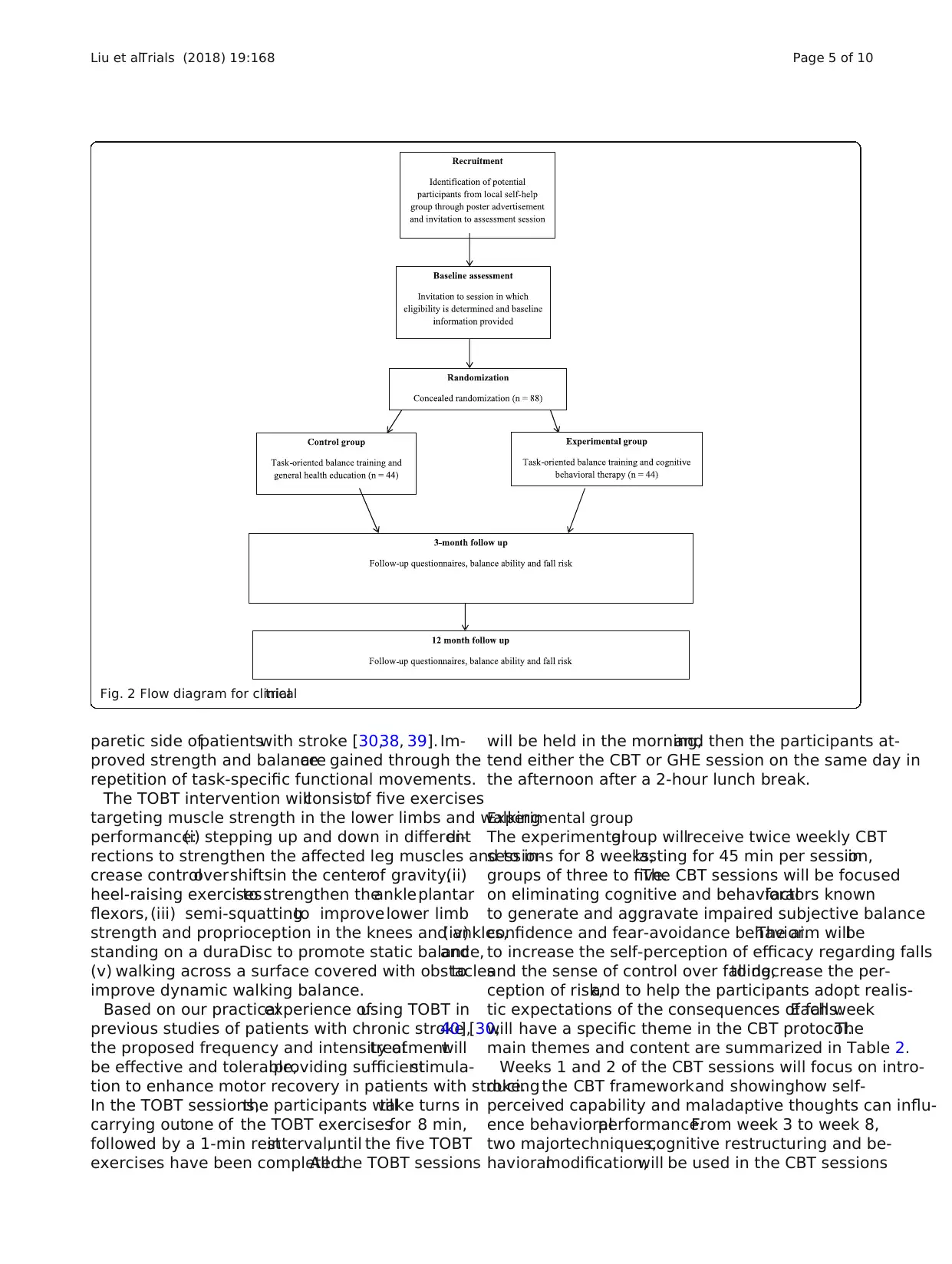

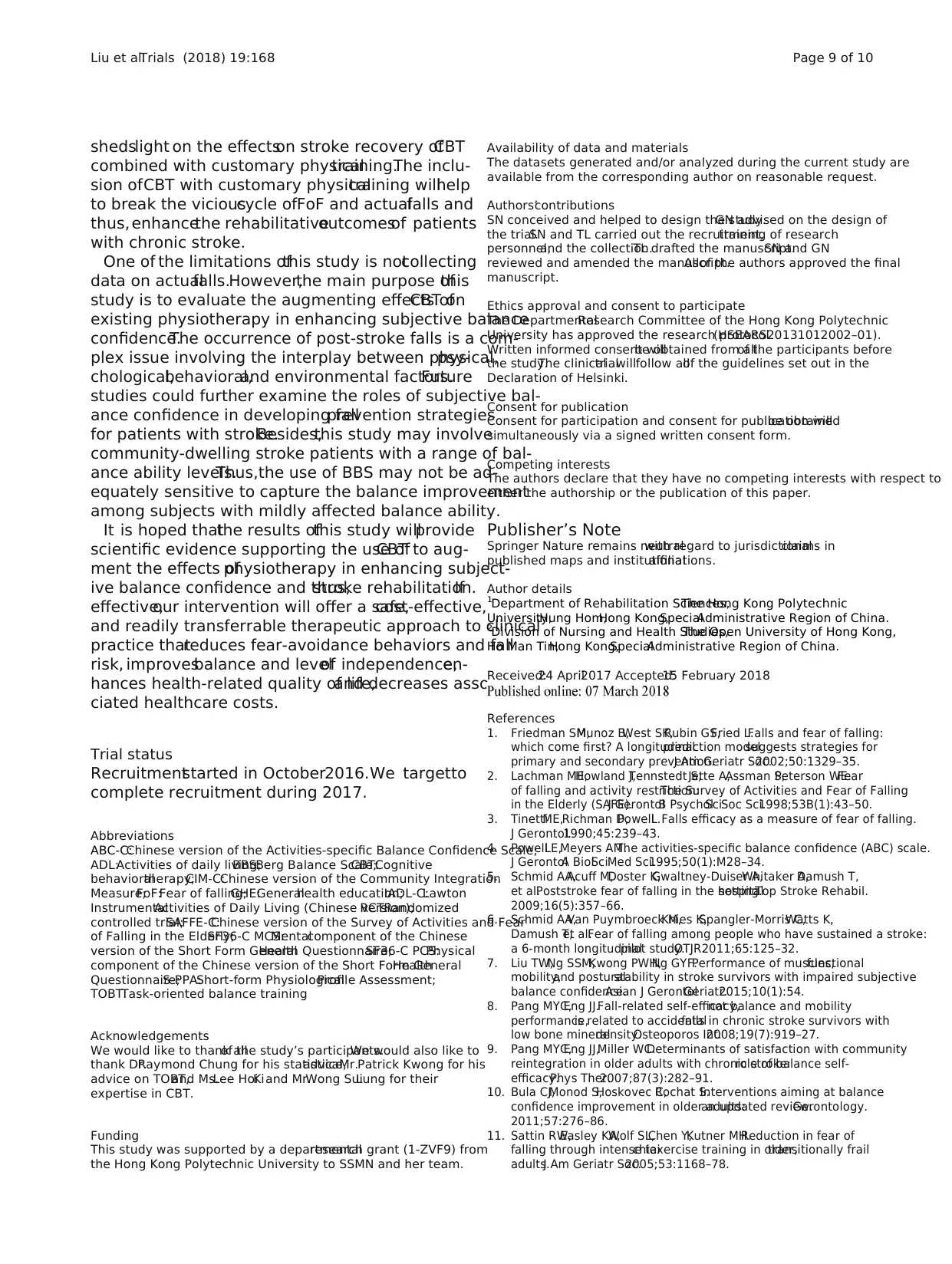

All of the participants willbe required to undergo five

sets of measurements(Fig. 1): (i) beforeassessment

(baseline treatment),(ii) after eight sessions of treatment

(midway through treatment),(iii) after16 sessionsof

treatment(end oftreatment),(iv) 12 weeks after treat-

ment (follow-up),and (v) 12 monthsaftertreatment

(follow-up).All of the assessmentprocedureswill be

performed by a research assistant blind to the group al-

location and notpreviously involved in the delivery of

the interventions.

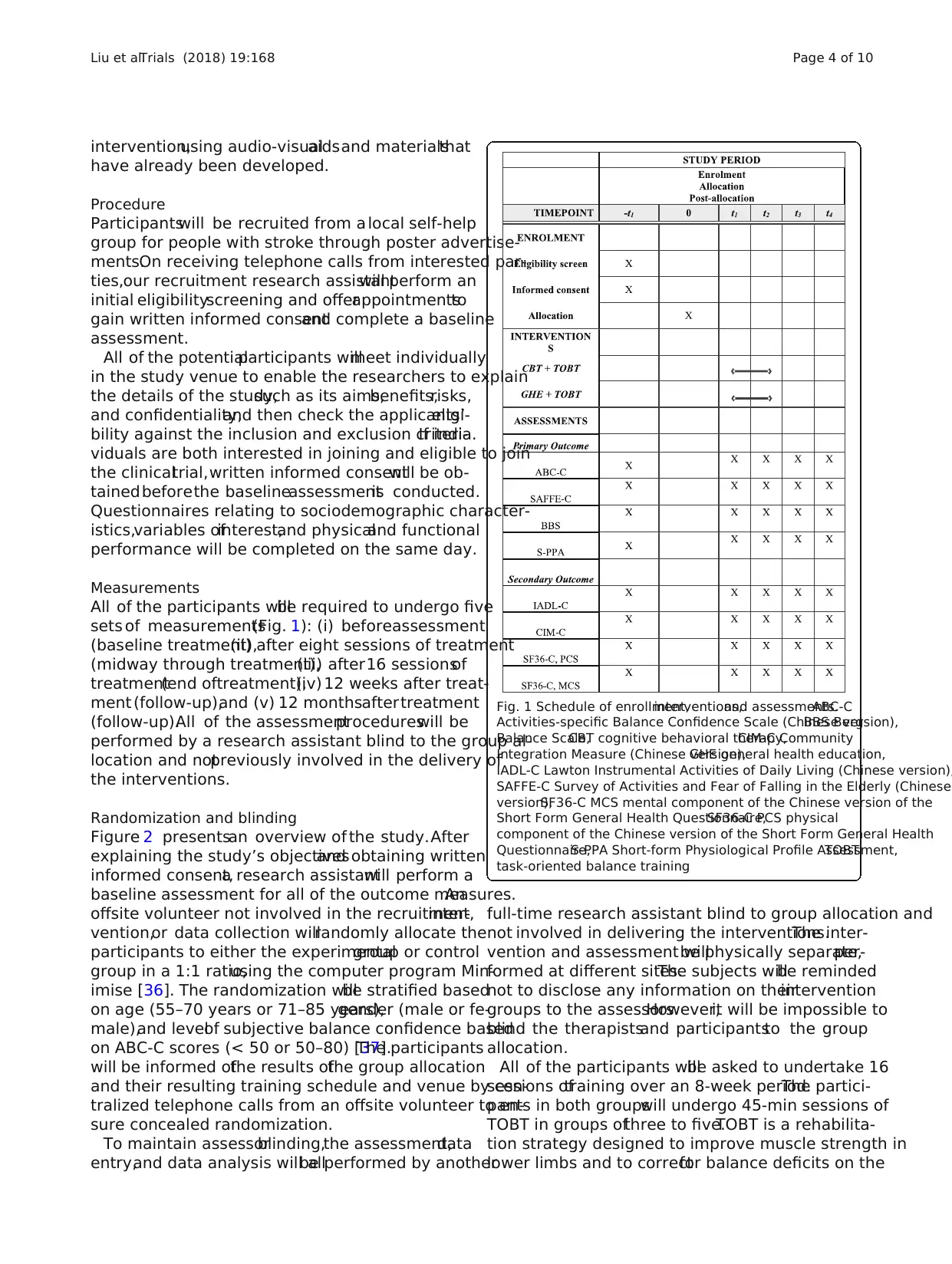

Randomization and blinding

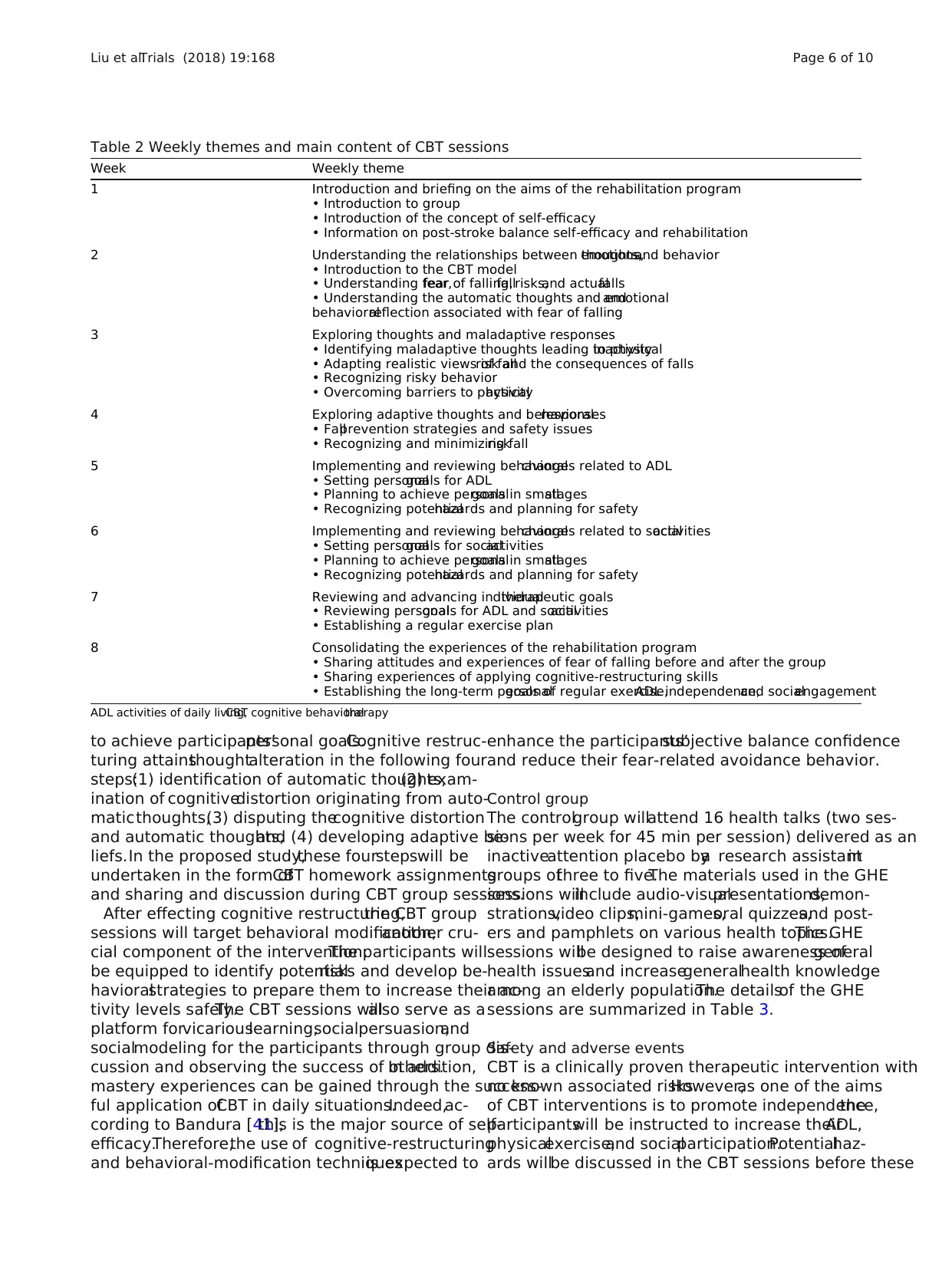

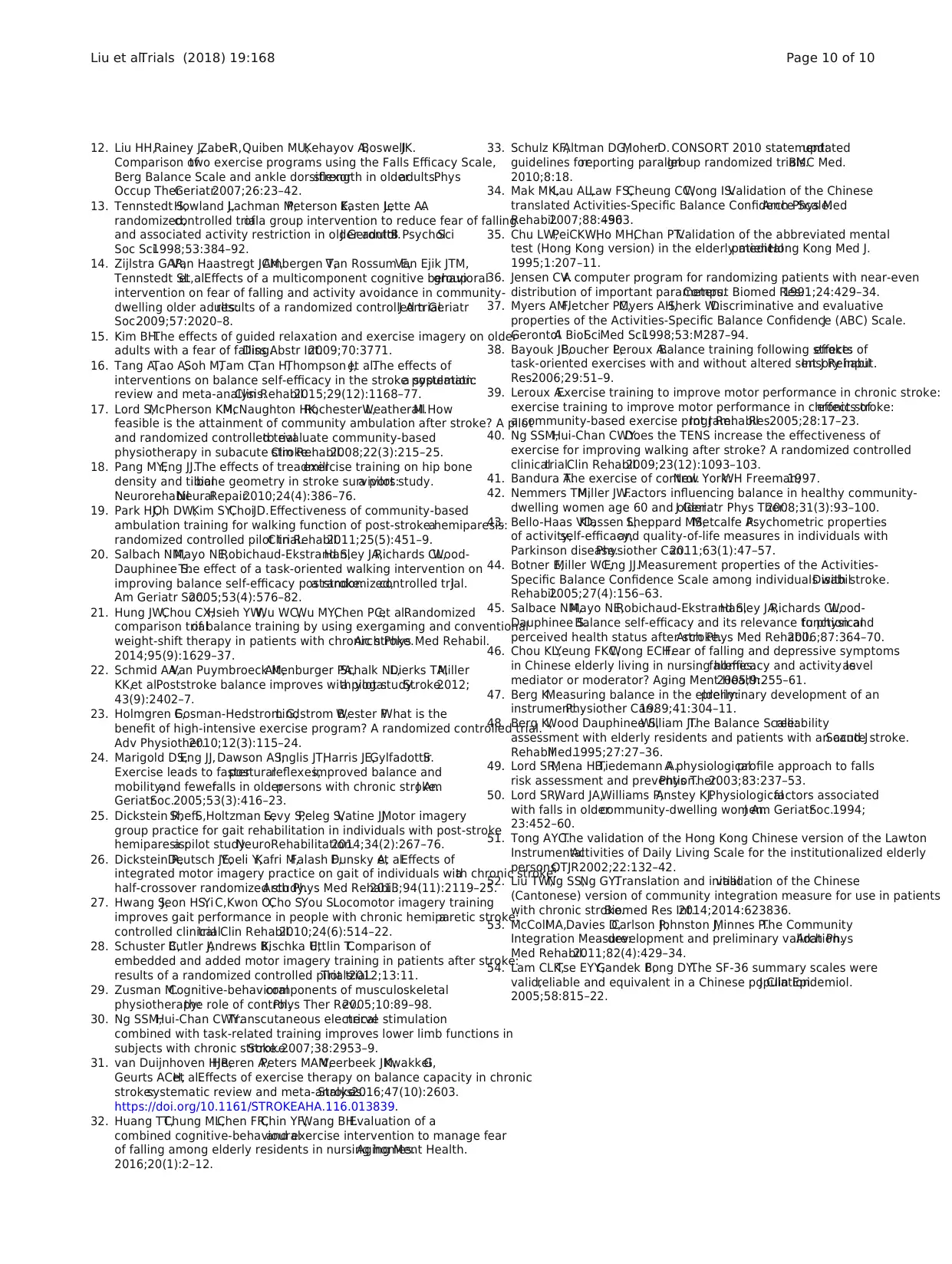

Figure 2 presentsan overview of the study.After

explaining the study’s objectivesand obtaining written

informed consent,a research assistantwill perform a

baseline assessment for all of the outcome measures.An

offsite volunteer not involved in the recruitment,inter-

vention,or data collection willrandomly allocate the

participants to either the experimentalgroup or control

group in a 1:1 ratio,using the computer program Min-

imise [36]. The randomization willbe stratified based

on age (55–70 years or 71–85 years),gender (male or fe-

male),and levelof subjective balance confidence based

on ABC-C scores (< 50 or 50–80) [37].The participants

will be informed ofthe results ofthe group allocation

and their resulting training schedule and venue by cen-

tralized telephone calls from an offsite volunteer to en-

sure concealed randomization.

To maintain assessorblinding,the assessment,data

entry,and data analysis will allbe performed by another

full-time research assistant blind to group allocation and

not involved in delivering the interventions.The inter-

vention and assessment willbe physically separate,per-

formed at different sites.The subjects willbe reminded

not to disclose any information on theirintervention

groups to the assessors.However,it will be impossible to

blind the therapistsand participantsto the group

allocation.

All of the participants willbe asked to undertake 16

sessions oftraining over an 8-week period.The partici-

pants in both groupswill undergo 45-min sessions of

TOBT in groups ofthree to five.TOBT is a rehabilita-

tion strategy designed to improve muscle strength in

lower limbs and to correctfor balance deficits on the

Fig. 1 Schedule of enrollment,interventions,and assessments.ABC-C

Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (Chinese version),BBS Berg

Balance Scale,CBT cognitive behavioral therapy,CIM-C Community

Integration Measure (Chinese version),GHE general health education,

IADL-C Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Chinese version),

SAFFE-C Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly (Chinese

version),SF36-C MCS mental component of the Chinese version of the

Short Form General Health Questionnaire,SF36-C PCS physical

component of the Chinese version of the Short Form General Health

Questionnaire,S-PPA Short-form Physiological Profile Assessment,TOBT

task-oriented balance training

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 4 of 10

have already been developed.

Procedure

Participantswill be recruited from a local self-help

group for people with stroke through poster advertise-

ments.On receiving telephone calls from interested par-

ties,our recruitment research assistantwill perform an

initial eligibilityscreening and offerappointmentsto

gain written informed consentand complete a baseline

assessment.

All of the potentialparticipants willmeet individually

in the study venue to enable the researchers to explain

the details of the study,such as its aims,benefits,risks,

and confidentiality,and then check the applicants’eligi-

bility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.If indi-

viduals are both interested in joining and eligible to join

the clinicaltrial,written informed consentwill be ob-

tainedbeforethe baselineassessmentis conducted.

Questionnaires relating to sociodemographic character-

istics,variables ofinterest,and physicaland functional

performance will be completed on the same day.

Measurements

All of the participants willbe required to undergo five

sets of measurements(Fig. 1): (i) beforeassessment

(baseline treatment),(ii) after eight sessions of treatment

(midway through treatment),(iii) after16 sessionsof

treatment(end oftreatment),(iv) 12 weeks after treat-

ment (follow-up),and (v) 12 monthsaftertreatment

(follow-up).All of the assessmentprocedureswill be

performed by a research assistant blind to the group al-

location and notpreviously involved in the delivery of

the interventions.

Randomization and blinding

Figure 2 presentsan overview of the study.After

explaining the study’s objectivesand obtaining written

informed consent,a research assistantwill perform a

baseline assessment for all of the outcome measures.An

offsite volunteer not involved in the recruitment,inter-

vention,or data collection willrandomly allocate the

participants to either the experimentalgroup or control

group in a 1:1 ratio,using the computer program Min-

imise [36]. The randomization willbe stratified based

on age (55–70 years or 71–85 years),gender (male or fe-

male),and levelof subjective balance confidence based

on ABC-C scores (< 50 or 50–80) [37].The participants

will be informed ofthe results ofthe group allocation

and their resulting training schedule and venue by cen-

tralized telephone calls from an offsite volunteer to en-

sure concealed randomization.

To maintain assessorblinding,the assessment,data

entry,and data analysis will allbe performed by another

full-time research assistant blind to group allocation and

not involved in delivering the interventions.The inter-

vention and assessment willbe physically separate,per-

formed at different sites.The subjects willbe reminded

not to disclose any information on theirintervention

groups to the assessors.However,it will be impossible to

blind the therapistsand participantsto the group

allocation.

All of the participants willbe asked to undertake 16

sessions oftraining over an 8-week period.The partici-

pants in both groupswill undergo 45-min sessions of

TOBT in groups ofthree to five.TOBT is a rehabilita-

tion strategy designed to improve muscle strength in

lower limbs and to correctfor balance deficits on the

Fig. 1 Schedule of enrollment,interventions,and assessments.ABC-C

Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (Chinese version),BBS Berg

Balance Scale,CBT cognitive behavioral therapy,CIM-C Community

Integration Measure (Chinese version),GHE general health education,

IADL-C Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Chinese version),

SAFFE-C Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly (Chinese

version),SF36-C MCS mental component of the Chinese version of the

Short Form General Health Questionnaire,SF36-C PCS physical

component of the Chinese version of the Short Form General Health

Questionnaire,S-PPA Short-form Physiological Profile Assessment,TOBT

task-oriented balance training

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 4 of 10

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

paretic side ofpatientswith stroke [30,38, 39]. Im-

proved strength and balanceare gained through the

repetition of task-specific functional movements.

The TOBT intervention willconsistof five exercises

targeting muscle strength in the lower limbs and walking

performance:(i) stepping up and down in differentdi-

rections to strengthen the affected leg muscles and to in-

crease controlovershiftsin the centerof gravity,(ii)

heel-raising exercisesto strengthen theankleplantar

flexors, (iii) semi-squattingto improvelower limb

strength and proprioception in the knees and ankles,(iv)

standing on a duraDisc to promote static balance,and

(v) walking across a surface covered with obstaclesto

improve dynamic walking balance.

Based on our practicalexperience ofusing TOBT in

previous studies of patients with chronic stroke [30,40],

the proposed frequency and intensity oftreatmentwill

be effective and tolerable,providing sufficientstimula-

tion to enhance motor recovery in patients with stroke.

In the TOBT sessions,the participants willtake turns in

carrying outone of the TOBT exercisesfor 8 min,

followed by a 1-min restinterval,until the five TOBT

exercises have been completed.All the TOBT sessions

will be held in the morning,and then the participants at-

tend either the CBT or GHE session on the same day in

the afternoon after a 2-hour lunch break.

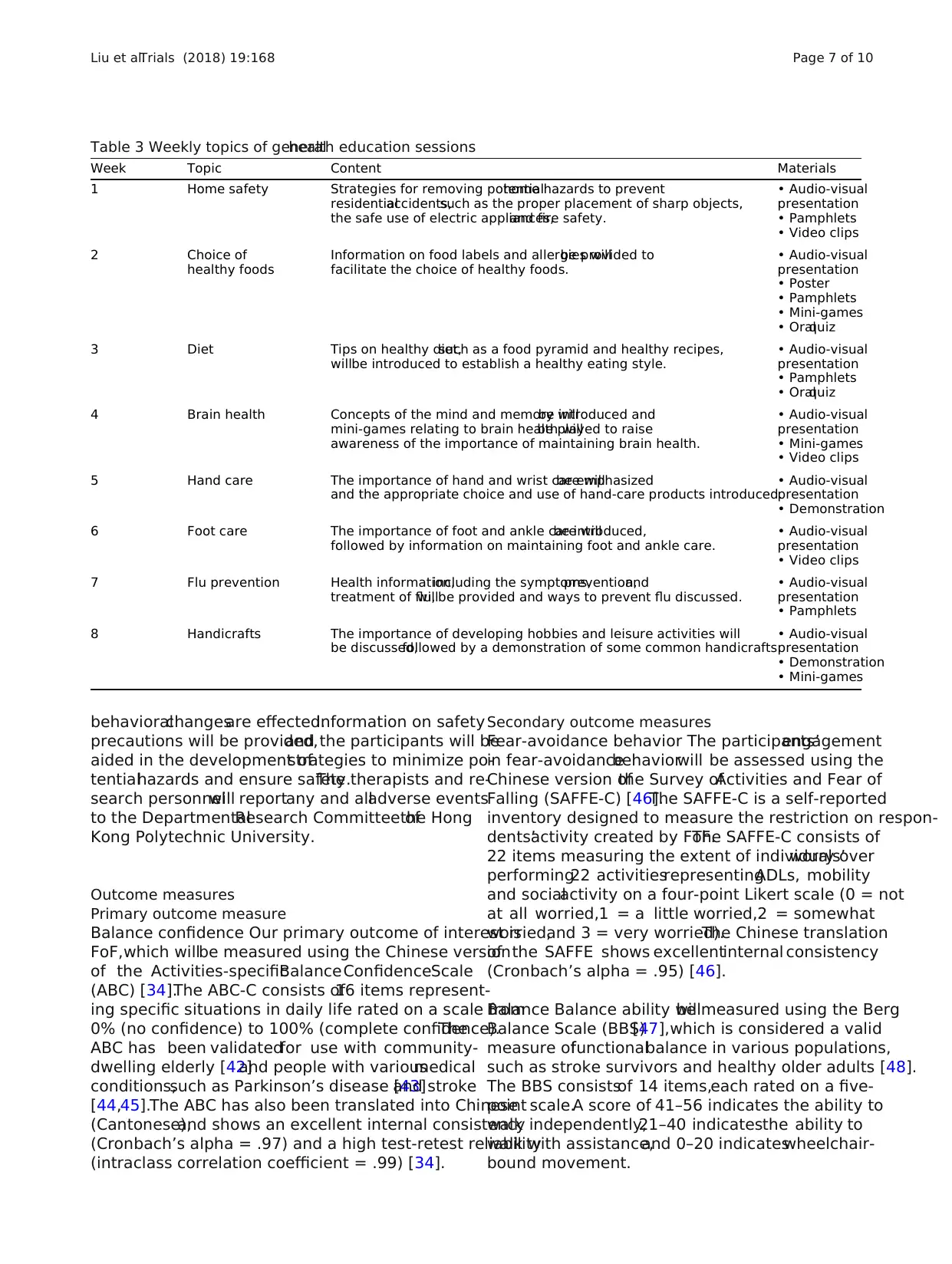

Experimental group

The experimentalgroup willreceive twice weekly CBT

sessions for 8 weeks,lasting for 45 min per session,in

groups of three to five.The CBT sessions will be focused

on eliminating cognitive and behavioralfactors known

to generate and aggravate impaired subjective balance

confidence and fear-avoidance behavior.The aim willbe

to increase the self-perception of efficacy regarding falls

and the sense of control over falling,to decrease the per-

ception of risk,and to help the participants adopt realis-

tic expectations of the consequences of falls.Each week

will have a specific theme in the CBT protocol.The

main themes and content are summarized in Table 2.

Weeks 1 and 2 of the CBT sessions will focus on intro-

ducing the CBT frameworkand showinghow self-

perceived capability and maladaptive thoughts can influ-

ence behavioralperformance.From week 3 to week 8,

two majortechniques,cognitive restructuring and be-

havioralmodification,will be used in the CBT sessions

Fig. 2 Flow diagram for clinicaltrial

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 5 of 10

proved strength and balanceare gained through the

repetition of task-specific functional movements.

The TOBT intervention willconsistof five exercises

targeting muscle strength in the lower limbs and walking

performance:(i) stepping up and down in differentdi-

rections to strengthen the affected leg muscles and to in-

crease controlovershiftsin the centerof gravity,(ii)

heel-raising exercisesto strengthen theankleplantar

flexors, (iii) semi-squattingto improvelower limb

strength and proprioception in the knees and ankles,(iv)

standing on a duraDisc to promote static balance,and

(v) walking across a surface covered with obstaclesto

improve dynamic walking balance.

Based on our practicalexperience ofusing TOBT in

previous studies of patients with chronic stroke [30,40],

the proposed frequency and intensity oftreatmentwill

be effective and tolerable,providing sufficientstimula-

tion to enhance motor recovery in patients with stroke.

In the TOBT sessions,the participants willtake turns in

carrying outone of the TOBT exercisesfor 8 min,

followed by a 1-min restinterval,until the five TOBT

exercises have been completed.All the TOBT sessions

will be held in the morning,and then the participants at-

tend either the CBT or GHE session on the same day in

the afternoon after a 2-hour lunch break.

Experimental group

The experimentalgroup willreceive twice weekly CBT

sessions for 8 weeks,lasting for 45 min per session,in

groups of three to five.The CBT sessions will be focused

on eliminating cognitive and behavioralfactors known

to generate and aggravate impaired subjective balance

confidence and fear-avoidance behavior.The aim willbe

to increase the self-perception of efficacy regarding falls

and the sense of control over falling,to decrease the per-

ception of risk,and to help the participants adopt realis-

tic expectations of the consequences of falls.Each week

will have a specific theme in the CBT protocol.The

main themes and content are summarized in Table 2.

Weeks 1 and 2 of the CBT sessions will focus on intro-

ducing the CBT frameworkand showinghow self-

perceived capability and maladaptive thoughts can influ-

ence behavioralperformance.From week 3 to week 8,

two majortechniques,cognitive restructuring and be-

havioralmodification,will be used in the CBT sessions

Fig. 2 Flow diagram for clinicaltrial

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 5 of 10

to achieve participants’personal goals.Cognitive restruc-

turing attainsthoughtalteration in the following four

steps:(1) identification of automatic thoughts,(2) exam-

ination of cognitivedistortion originating from auto-

maticthoughts,(3) disputing thecognitive distortion

and automatic thoughts,and (4) developing adaptive be-

liefs.In the proposed study,these fourstepswill be

undertaken in the form ofCBT homework assignments

and sharing and discussion during CBT group sessions.

After effecting cognitive restructuring,the CBT group

sessions will target behavioral modification,another cru-

cial component of the intervention.The participants will

be equipped to identify potentialrisks and develop be-

havioralstrategies to prepare them to increase their ac-

tivity levels safely.The CBT sessions willalso serve as a

platform forvicariouslearning,socialpersuasion,and

socialmodeling for the participants through group dis-

cussion and observing the success of others.In addition,

mastery experiences can be gained through the success-

ful application ofCBT in daily situations.Indeed,ac-

cording to Bandura [41],this is the major source of self-

efficacy.Therefore,the use of cognitive-restructuring

and behavioral-modification techniquesis expected to

enhance the participants’subjective balance confidence

and reduce their fear-related avoidance behavior.

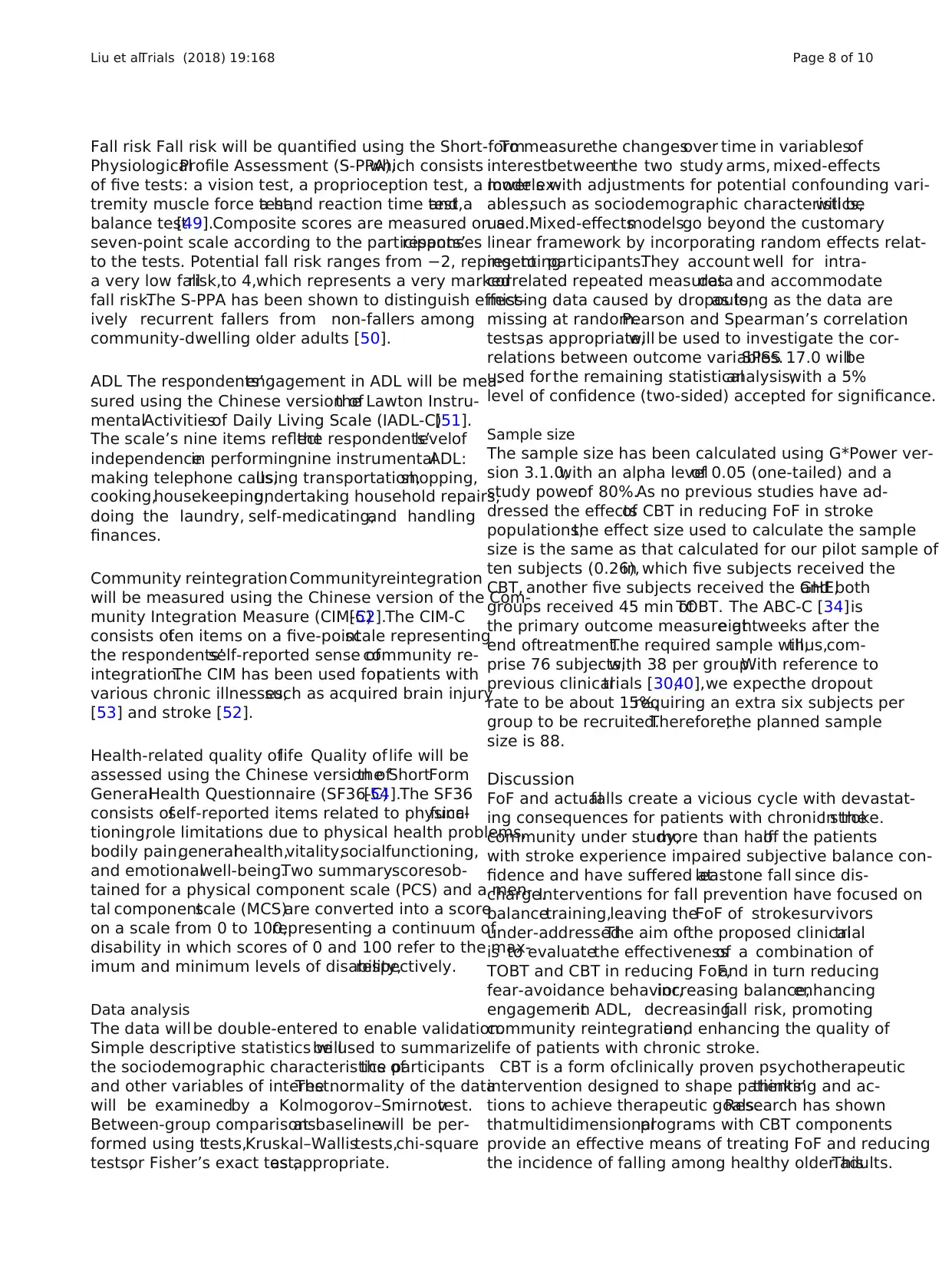

Control group

The controlgroup willattend 16 health talks (two ses-

sions per week for 45 min per session) delivered as an

inactiveattention placebo bya research assistantin

groups ofthree to five.The materials used in the GHE

sessions willinclude audio-visualpresentations,demon-

strations,video clips,mini-games,oral quizzes,and post-

ers and pamphlets on various health topics.The GHE

sessions willbe designed to raise awareness ofgeneral

health issuesand increasegeneralhealth knowledge

among an elderly population.The detailsof the GHE

sessions are summarized in Table 3.

Safety and adverse events

CBT is a clinically proven therapeutic intervention with

no known associated risks.However,as one of the aims

of CBT interventions is to promote independence,the

participantswill be instructed to increase theirADL,

physicalexercise,and socialparticipation.Potentialhaz-

ards willbe discussed in the CBT sessions before these

Table 2 Weekly themes and main content of CBT sessions

Week Weekly theme

1 Introduction and briefing on the aims of the rehabilitation program

• Introduction to group

• Introduction of the concept of self-efficacy

• Information on post-stroke balance self-efficacy and rehabilitation

2 Understanding the relationships between thoughts,emotions,and behavior

• Introduction to the CBT model

• Understanding fear,fear of falling,fallrisks,and actualfalls

• Understanding the automatic thoughts and emotionaland

behavioralreflection associated with fear of falling

3 Exploring thoughts and maladaptive responses

• Identifying maladaptive thoughts leading to physicalinactivity

• Adapting realistic views of fallrisk and the consequences of falls

• Recognizing risky behavior

• Overcoming barriers to physicalactivity

4 Exploring adaptive thoughts and behavioralresponses

• Fallprevention strategies and safety issues

• Recognizing and minimizing fallrisk

5 Implementing and reviewing behavioralchanges related to ADL

• Setting personalgoals for ADL

• Planning to achieve personalgoals in smallstages

• Recognizing potentialhazards and planning for safety

6 Implementing and reviewing behavioralchanges related to socialactivities

• Setting personalgoals for socialactivities

• Planning to achieve personalgoals in smallstages

• Recognizing potentialhazards and planning for safety

7 Reviewing and advancing individualtherapeutic goals

• Reviewing personalgoals for ADL and socialactivities

• Establishing a regular exercise plan

8 Consolidating the experiences of the rehabilitation program

• Sharing attitudes and experiences of fear of falling before and after the group

• Sharing experiences of applying cognitive-restructuring skills

• Establishing the long-term personalgoals of regular exercise,ADL independence,and socialengagement

ADL activities of daily living,CBT cognitive behavioraltherapy

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 6 of 10

turing attainsthoughtalteration in the following four

steps:(1) identification of automatic thoughts,(2) exam-

ination of cognitivedistortion originating from auto-

maticthoughts,(3) disputing thecognitive distortion

and automatic thoughts,and (4) developing adaptive be-

liefs.In the proposed study,these fourstepswill be

undertaken in the form ofCBT homework assignments

and sharing and discussion during CBT group sessions.

After effecting cognitive restructuring,the CBT group

sessions will target behavioral modification,another cru-

cial component of the intervention.The participants will

be equipped to identify potentialrisks and develop be-

havioralstrategies to prepare them to increase their ac-

tivity levels safely.The CBT sessions willalso serve as a

platform forvicariouslearning,socialpersuasion,and

socialmodeling for the participants through group dis-

cussion and observing the success of others.In addition,

mastery experiences can be gained through the success-

ful application ofCBT in daily situations.Indeed,ac-

cording to Bandura [41],this is the major source of self-

efficacy.Therefore,the use of cognitive-restructuring

and behavioral-modification techniquesis expected to

enhance the participants’subjective balance confidence

and reduce their fear-related avoidance behavior.

Control group

The controlgroup willattend 16 health talks (two ses-

sions per week for 45 min per session) delivered as an

inactiveattention placebo bya research assistantin

groups ofthree to five.The materials used in the GHE

sessions willinclude audio-visualpresentations,demon-

strations,video clips,mini-games,oral quizzes,and post-

ers and pamphlets on various health topics.The GHE

sessions willbe designed to raise awareness ofgeneral

health issuesand increasegeneralhealth knowledge

among an elderly population.The detailsof the GHE

sessions are summarized in Table 3.

Safety and adverse events

CBT is a clinically proven therapeutic intervention with

no known associated risks.However,as one of the aims

of CBT interventions is to promote independence,the

participantswill be instructed to increase theirADL,

physicalexercise,and socialparticipation.Potentialhaz-

ards willbe discussed in the CBT sessions before these

Table 2 Weekly themes and main content of CBT sessions

Week Weekly theme

1 Introduction and briefing on the aims of the rehabilitation program

• Introduction to group

• Introduction of the concept of self-efficacy

• Information on post-stroke balance self-efficacy and rehabilitation

2 Understanding the relationships between thoughts,emotions,and behavior

• Introduction to the CBT model

• Understanding fear,fear of falling,fallrisks,and actualfalls

• Understanding the automatic thoughts and emotionaland

behavioralreflection associated with fear of falling

3 Exploring thoughts and maladaptive responses

• Identifying maladaptive thoughts leading to physicalinactivity

• Adapting realistic views of fallrisk and the consequences of falls

• Recognizing risky behavior

• Overcoming barriers to physicalactivity

4 Exploring adaptive thoughts and behavioralresponses

• Fallprevention strategies and safety issues

• Recognizing and minimizing fallrisk

5 Implementing and reviewing behavioralchanges related to ADL

• Setting personalgoals for ADL

• Planning to achieve personalgoals in smallstages

• Recognizing potentialhazards and planning for safety

6 Implementing and reviewing behavioralchanges related to socialactivities

• Setting personalgoals for socialactivities

• Planning to achieve personalgoals in smallstages

• Recognizing potentialhazards and planning for safety

7 Reviewing and advancing individualtherapeutic goals

• Reviewing personalgoals for ADL and socialactivities

• Establishing a regular exercise plan

8 Consolidating the experiences of the rehabilitation program

• Sharing attitudes and experiences of fear of falling before and after the group

• Sharing experiences of applying cognitive-restructuring skills

• Establishing the long-term personalgoals of regular exercise,ADL independence,and socialengagement

ADL activities of daily living,CBT cognitive behavioraltherapy

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 6 of 10

behavioralchangesare effected.Information on safety

precautions will be provided,and the participants will be

aided in the development ofstrategies to minimize po-

tentialhazards and ensure safety.The therapists and re-

search personnelwill reportany and alladverse events

to the DepartmentalResearch Committee ofthe Hong

Kong Polytechnic University.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Balance confidence Our primary outcome of interest is

FoF,which willbe measured using the Chinese version

of the Activities-specificBalanceConfidenceScale

(ABC) [34].The ABC-C consists of16 items represent-

ing specific situations in daily life rated on a scale from

0% (no confidence) to 100% (complete confidence).The

ABC has been validatedfor use with community-

dwelling elderly [42]and people with variousmedical

conditions,such as Parkinson’s disease [43]and stroke

[44,45].The ABC has also been translated into Chinese

(Cantonese),and shows an excellent internal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha = .97) and a high test-retest reliability

(intraclass correlation coefficient = .99) [34].

Secondary outcome measures

Fear-avoidance behavior The participants’engagement

in fear-avoidancebehaviorwill be assessed using the

Chinese version ofthe Survey ofActivities and Fear of

Falling (SAFFE-C) [46].The SAFFE-C is a self-reported

inventory designed to measure the restriction on respon-

dents’activity created by FoF.The SAFFE-C consists of

22 items measuring the extent of individuals’worry over

performing22 activitiesrepresentingADLs, mobility

and socialactivity on a four-point Likert scale (0 = not

at all worried,1 = a little worried,2 = somewhat

worried,and 3 = very worried).The Chinese translation

of the SAFFE shows excellentinternal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha = .95) [46].

Balance Balance ability willbe measured using the Berg

Balance Scale (BBS)[47],which is considered a valid

measure offunctionalbalance in various populations,

such as stroke survivors and healthy older adults [48].

The BBS consistsof 14 items,each rated on a five-

point scale.A score of 41–56 indicates the ability to

walk independently,21–40 indicatesthe ability to

walk with assistance,and 0–20 indicateswheelchair-

bound movement.

Table 3 Weekly topics of generalhealth education sessions

Week Topic Content Materials

1 Home safety Strategies for removing potentialhome hazards to prevent

residentialaccidents,such as the proper placement of sharp objects,

the safe use of electric appliances,and fire safety.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

• Video clips

2 Choice of

healthy foods

Information on food labels and allergies willbe provided to

facilitate the choice of healthy foods.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Poster

• Pamphlets

• Mini-games

• Oralquiz

3 Diet Tips on healthy diet,such as a food pyramid and healthy recipes,

willbe introduced to establish a healthy eating style.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

• Oralquiz

4 Brain health Concepts of the mind and memory willbe introduced and

mini-games relating to brain health willbe played to raise

awareness of the importance of maintaining brain health.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Mini-games

• Video clips

5 Hand care The importance of hand and wrist care willbe emphasized

and the appropriate choice and use of hand-care products introduced.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Demonstration

6 Foot care The importance of foot and ankle care willbe introduced,

followed by information on maintaining foot and ankle care.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Video clips

7 Flu prevention Health information,including the symptoms,prevention,and

treatment of flu,willbe provided and ways to prevent flu discussed.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

8 Handicrafts The importance of developing hobbies and leisure activities will

be discussed,followed by a demonstration of some common handicrafts.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Demonstration

• Mini-games

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 7 of 10

precautions will be provided,and the participants will be

aided in the development ofstrategies to minimize po-

tentialhazards and ensure safety.The therapists and re-

search personnelwill reportany and alladverse events

to the DepartmentalResearch Committee ofthe Hong

Kong Polytechnic University.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Balance confidence Our primary outcome of interest is

FoF,which willbe measured using the Chinese version

of the Activities-specificBalanceConfidenceScale

(ABC) [34].The ABC-C consists of16 items represent-

ing specific situations in daily life rated on a scale from

0% (no confidence) to 100% (complete confidence).The

ABC has been validatedfor use with community-

dwelling elderly [42]and people with variousmedical

conditions,such as Parkinson’s disease [43]and stroke

[44,45].The ABC has also been translated into Chinese

(Cantonese),and shows an excellent internal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha = .97) and a high test-retest reliability

(intraclass correlation coefficient = .99) [34].

Secondary outcome measures

Fear-avoidance behavior The participants’engagement

in fear-avoidancebehaviorwill be assessed using the

Chinese version ofthe Survey ofActivities and Fear of

Falling (SAFFE-C) [46].The SAFFE-C is a self-reported

inventory designed to measure the restriction on respon-

dents’activity created by FoF.The SAFFE-C consists of

22 items measuring the extent of individuals’worry over

performing22 activitiesrepresentingADLs, mobility

and socialactivity on a four-point Likert scale (0 = not

at all worried,1 = a little worried,2 = somewhat

worried,and 3 = very worried).The Chinese translation

of the SAFFE shows excellentinternal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha = .95) [46].

Balance Balance ability willbe measured using the Berg

Balance Scale (BBS)[47],which is considered a valid

measure offunctionalbalance in various populations,

such as stroke survivors and healthy older adults [48].

The BBS consistsof 14 items,each rated on a five-

point scale.A score of 41–56 indicates the ability to

walk independently,21–40 indicatesthe ability to

walk with assistance,and 0–20 indicateswheelchair-

bound movement.

Table 3 Weekly topics of generalhealth education sessions

Week Topic Content Materials

1 Home safety Strategies for removing potentialhome hazards to prevent

residentialaccidents,such as the proper placement of sharp objects,

the safe use of electric appliances,and fire safety.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

• Video clips

2 Choice of

healthy foods

Information on food labels and allergies willbe provided to

facilitate the choice of healthy foods.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Poster

• Pamphlets

• Mini-games

• Oralquiz

3 Diet Tips on healthy diet,such as a food pyramid and healthy recipes,

willbe introduced to establish a healthy eating style.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

• Oralquiz

4 Brain health Concepts of the mind and memory willbe introduced and

mini-games relating to brain health willbe played to raise

awareness of the importance of maintaining brain health.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Mini-games

• Video clips

5 Hand care The importance of hand and wrist care willbe emphasized

and the appropriate choice and use of hand-care products introduced.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Demonstration

6 Foot care The importance of foot and ankle care willbe introduced,

followed by information on maintaining foot and ankle care.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Video clips

7 Flu prevention Health information,including the symptoms,prevention,and

treatment of flu,willbe provided and ways to prevent flu discussed.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Pamphlets

8 Handicrafts The importance of developing hobbies and leisure activities will

be discussed,followed by a demonstration of some common handicrafts.

• Audio-visual

presentation

• Demonstration

• Mini-games

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 7 of 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Fall risk Fall risk will be quantified using the Short-form

PhysiologicalProfile Assessment (S-PPA),which consists

of five tests: a vision test, a proprioception test, a lower ex-

tremity muscle force test,a hand reaction time test,and a

balance test[49].Composite scores are measured on a

seven-point scale according to the participants’responses

to the tests. Potential fall risk ranges from −2, representing

a very low fallrisk,to 4,which represents a very marked

fall risk.The S-PPA has been shown to distinguish effect-

ively recurrent fallers from non-fallers among

community-dwelling older adults [50].

ADL The respondents’engagement in ADL will be mea-

sured using the Chinese version ofthe Lawton Instru-

mentalActivitiesof Daily Living Scale (IADL-C)[51].

The scale’s nine items reflectthe respondents’levelof

independencein performingnine instrumentalADL:

making telephone calls,using transportation,shopping,

cooking,housekeeping,undertaking household repairs,

doing the laundry, self-medicating,and handling

finances.

Community reintegration Communityreintegration

will be measured using the Chinese version of the Com-

munity Integration Measure (CIM-C)[52].The CIM-C

consists often items on a five-pointscale representing

the respondents’self-reported sense ofcommunity re-

integration.The CIM has been used forpatients with

various chronic illnesses,such as acquired brain injury

[53] and stroke [52].

Health-related quality oflife Quality oflife will be

assessed using the Chinese version ofthe ShortForm

GeneralHealth Questionnaire (SF36-C)[54].The SF36

consists ofself-reported items related to physicalfunc-

tioning,role limitations due to physical health problems,

bodily pain,generalhealth,vitality,socialfunctioning,

and emotionalwell-being.Two summaryscoresob-

tained for a physical component scale (PCS) and a men-

tal componentscale (MCS)are converted into a score

on a scale from 0 to 100,representing a continuum of

disability in which scores of 0 and 100 refer to the max-

imum and minimum levels of disability,respectively.

Data analysis

The data will be double-entered to enable validation.

Simple descriptive statistics willbe used to summarize

the sociodemographic characteristics ofthe participants

and other variables of interest.The normality of the data

will be examinedby a Kolmogorov–Smirnovtest.

Between-group comparisonsat baselinewill be per-

formed using ttests,Kruskal–Wallistests,chi-square

tests,or Fisher’s exact test,as appropriate.

To measurethe changesover time in variablesof

interestbetweenthe two study arms, mixed-effects

models with adjustments for potential confounding vari-

ables,such as sociodemographic characteristics,will be

used.Mixed-effectsmodelsgo beyond the customary

linear framework by incorporating random effects relat-

ing to participants.They account well for intra-

correlated repeated measuresdata and accommodate

missing data caused by dropouts,as long as the data are

missing at random.Pearson and Spearman’s correlation

tests,as appropriate,will be used to investigate the cor-

relations between outcome variables.SPSS 17.0 willbe

used for the remaining statisticalanalysis,with a 5%

level of confidence (two-sided) accepted for significance.

Sample size

The sample size has been calculated using G*Power ver-

sion 3.1.0,with an alpha levelof 0.05 (one-tailed) and a

study powerof 80%.As no previous studies have ad-

dressed the effectsof CBT in reducing FoF in stroke

populations,the effect size used to calculate the sample

size is the same as that calculated for our pilot sample of

ten subjects (0.26),in which five subjects received the

CBT, another five subjects received the GHE,and both

groups received 45 min ofTOBT. The ABC-C [34]is

the primary outcome measure ateightweeks after the

end oftreatment.The required sample will,thus,com-

prise 76 subjects,with 38 per group.With reference to

previous clinicaltrials [30,40],we expectthe dropout

rate to be about 15%,requiring an extra six subjects per

group to be recruited.Therefore,the planned sample

size is 88.

Discussion

FoF and actualfalls create a vicious cycle with devastat-

ing consequences for patients with chronic stroke.In the

community under study,more than halfof the patients

with stroke experience impaired subjective balance con-

fidence and have suffered atleastone fall since dis-

charge.Interventions for fall prevention have focused on

balancetraining,leaving theFoF of strokesurvivors

under-addressed.The aim ofthe proposed clinicaltrial

is to evaluatethe effectivenessof a combination of

TOBT and CBT in reducing FoF,and in turn reducing

fear-avoidance behavior,increasing balance,enhancing

engagementin ADL, decreasingfall risk, promoting

community reintegration,and enhancing the quality of

life of patients with chronic stroke.

CBT is a form ofclinically proven psychotherapeutic

intervention designed to shape patients’thinking and ac-

tions to achieve therapeutic goals.Research has shown

thatmultidimensionalprograms with CBT components

provide an effective means of treating FoF and reducing

the incidence of falling among healthy older adults.This

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 8 of 10

PhysiologicalProfile Assessment (S-PPA),which consists

of five tests: a vision test, a proprioception test, a lower ex-

tremity muscle force test,a hand reaction time test,and a

balance test[49].Composite scores are measured on a

seven-point scale according to the participants’responses

to the tests. Potential fall risk ranges from −2, representing

a very low fallrisk,to 4,which represents a very marked

fall risk.The S-PPA has been shown to distinguish effect-

ively recurrent fallers from non-fallers among

community-dwelling older adults [50].

ADL The respondents’engagement in ADL will be mea-

sured using the Chinese version ofthe Lawton Instru-

mentalActivitiesof Daily Living Scale (IADL-C)[51].

The scale’s nine items reflectthe respondents’levelof

independencein performingnine instrumentalADL:

making telephone calls,using transportation,shopping,

cooking,housekeeping,undertaking household repairs,

doing the laundry, self-medicating,and handling

finances.

Community reintegration Communityreintegration

will be measured using the Chinese version of the Com-

munity Integration Measure (CIM-C)[52].The CIM-C

consists often items on a five-pointscale representing

the respondents’self-reported sense ofcommunity re-

integration.The CIM has been used forpatients with

various chronic illnesses,such as acquired brain injury

[53] and stroke [52].

Health-related quality oflife Quality oflife will be

assessed using the Chinese version ofthe ShortForm

GeneralHealth Questionnaire (SF36-C)[54].The SF36

consists ofself-reported items related to physicalfunc-

tioning,role limitations due to physical health problems,

bodily pain,generalhealth,vitality,socialfunctioning,

and emotionalwell-being.Two summaryscoresob-

tained for a physical component scale (PCS) and a men-

tal componentscale (MCS)are converted into a score

on a scale from 0 to 100,representing a continuum of

disability in which scores of 0 and 100 refer to the max-

imum and minimum levels of disability,respectively.

Data analysis

The data will be double-entered to enable validation.

Simple descriptive statistics willbe used to summarize

the sociodemographic characteristics ofthe participants

and other variables of interest.The normality of the data

will be examinedby a Kolmogorov–Smirnovtest.

Between-group comparisonsat baselinewill be per-

formed using ttests,Kruskal–Wallistests,chi-square

tests,or Fisher’s exact test,as appropriate.

To measurethe changesover time in variablesof

interestbetweenthe two study arms, mixed-effects

models with adjustments for potential confounding vari-

ables,such as sociodemographic characteristics,will be

used.Mixed-effectsmodelsgo beyond the customary

linear framework by incorporating random effects relat-

ing to participants.They account well for intra-

correlated repeated measuresdata and accommodate

missing data caused by dropouts,as long as the data are

missing at random.Pearson and Spearman’s correlation

tests,as appropriate,will be used to investigate the cor-

relations between outcome variables.SPSS 17.0 willbe

used for the remaining statisticalanalysis,with a 5%

level of confidence (two-sided) accepted for significance.

Sample size

The sample size has been calculated using G*Power ver-

sion 3.1.0,with an alpha levelof 0.05 (one-tailed) and a

study powerof 80%.As no previous studies have ad-

dressed the effectsof CBT in reducing FoF in stroke

populations,the effect size used to calculate the sample

size is the same as that calculated for our pilot sample of

ten subjects (0.26),in which five subjects received the

CBT, another five subjects received the GHE,and both

groups received 45 min ofTOBT. The ABC-C [34]is

the primary outcome measure ateightweeks after the

end oftreatment.The required sample will,thus,com-

prise 76 subjects,with 38 per group.With reference to

previous clinicaltrials [30,40],we expectthe dropout

rate to be about 15%,requiring an extra six subjects per

group to be recruited.Therefore,the planned sample

size is 88.

Discussion

FoF and actualfalls create a vicious cycle with devastat-

ing consequences for patients with chronic stroke.In the

community under study,more than halfof the patients

with stroke experience impaired subjective balance con-

fidence and have suffered atleastone fall since dis-

charge.Interventions for fall prevention have focused on

balancetraining,leaving theFoF of strokesurvivors

under-addressed.The aim ofthe proposed clinicaltrial

is to evaluatethe effectivenessof a combination of

TOBT and CBT in reducing FoF,and in turn reducing

fear-avoidance behavior,increasing balance,enhancing

engagementin ADL, decreasingfall risk, promoting

community reintegration,and enhancing the quality of

life of patients with chronic stroke.

CBT is a form ofclinically proven psychotherapeutic

intervention designed to shape patients’thinking and ac-

tions to achieve therapeutic goals.Research has shown

thatmultidimensionalprograms with CBT components

provide an effective means of treating FoF and reducing

the incidence of falling among healthy older adults.This

Liu et al.Trials (2018) 19:168 Page 8 of 10

shedslight on the effectson stroke recovery ofCBT

combined with customary physicaltraining.The inclu-

sion ofCBT with customary physicaltraining willhelp

to break the viciouscycle ofFoF and actualfalls and

thus, enhancethe rehabilitativeoutcomesof patients

with chronic stroke.

One of the limitations ofthis study is notcollecting

data on actualfalls.However,the main purpose ofthis

study is to evaluate the augmenting effects ofCBT on

existing physiotherapy in enhancing subjective balance

confidence.The occurrence of post-stroke falls is a com-

plex issue involving the interplay between physical,psy-

chological,behavioral,and environmental factors.Future

studies could further examine the roles of subjective bal-

ance confidence in developing fallprevention strategies

for patients with stroke.Besides,this study may involve

community-dwelling stroke patients with a range of bal-

ance ability levels.Thus,the use of BBS may not be ad-

equately sensitive to capture the balance improvement

among subjects with mildly affected balance ability.

It is hoped thatthe results ofthis study willprovide

scientific evidence supporting the use ofCBT to aug-

ment the effects ofphysiotherapy in enhancing subject-

ive balance confidence and thus,stroke rehabilitation.If

effective,our intervention will offer a safe,cost-effective,

and readily transferrable therapeutic approach to clinical

practice thatreduces fear-avoidance behaviors and fall

risk, improvesbalance and levelof independence,en-

hances health-related quality of life,and decreases asso-

ciated healthcare costs.

Trial status

Recruitmentstarted in October2016.We targetto

complete recruitment during 2017.

Abbreviations

ABC-C:Chinese version of the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale;

ADL:Activities of daily living;BBS:Berg Balance Scale;CBT:Cognitive

behavioraltherapy;CIM-C:Chinese version of the Community Integration

Measure;FoF:Fear of falling;GHE:Generalhealth education;IADL-C:Lawton

InstrumentalActivities of Daily Living (Chinese version);RCT:Randomized

controlled trial;SAFFE-C:Chinese version of the Survey of Activities and Fear

of Falling in the Elderly;SF36-C MCS:Mentalcomponent of the Chinese

version of the Short Form GeneralHealth Questionnaire;SF36-C PCS:Physical

component of the Chinese version of the Short Form GeneralHealth

Questionnaire;S-PPA:Short-form PhysiologicalProfile Assessment;

TOBT:Task-oriented balance training

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank allof the study’s participants.We would also like to

thank Dr.Raymond Chung for his statisticaladvice,Mr.Patrick Kwong for his

advice on TOBT,and Ms.Lee HoiKiand Mr.Wong SuiLung for their

expertise in CBT.

Funding