Impact of Language and Interpreters on Therapy Alliance Study

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/15

|11

|11921

|401

Report

AI Summary

This research article, "Effects of Language Concordance and Interpreter Use on Therapeutic Alliance in Spanish-Speaking Integrated Behavioral Health Care Patients" by Villalobos et al. (2016), investigates the impact of interpreter use and language concordance on the therapeutic alliance in a sample of 458 Spanish-speaking patients. The study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data from a therapeutic alliance scale with qualitative interviews of patients, behavioral health consultants, and interpreters. Quantitative findings revealed no significant relationship between interpreter use and therapeutic alliance. However, qualitative data highlighted patient preferences for bilingual providers, emphasizing trust, privacy, and ease of communication. While interpreters were seen as valuable for access to services, the study underscores the importance of interpreter training and collaboration to minimize potential negative impacts on care quality. The study contributes to the understanding of language barriers in mental health and the role of interpreters in bridging this gap.

Effects of Language Concordance and Interpreter Use on Therapeutic

Alliance in Spanish-Speaking Integrated Behavioral Health Care Patients

Bianca T. Villalobos, Ana J. Bridges, Elizabeth A. Anastasia, Carlos A. Ojeda,

Juventino Hernandez Rodriguez, and Debbie Gomez

University of Arkansas

The discrepancy between the growing number of Spanish speakers in the U.S. and the availability of

bilingual providers creates a barrier to accessing quality mental health care. Use of interpreters provides

one strategy for overcoming this linguistic barrier; however, concerns about whether sessions with

interpreters, versus bilingual providers, impede therapeutic alliance remain. The current study explored

associations between the use of interpreters and therapeutic alliance in a sample of 458 Spanish-speaking

patients seen for integrated behavioral health visits at primary care clinics. Patients completed a brief (4

item) therapeutic alliance scale at their behavioral health appointment. In addition, to supplement the

quantitative study data, a pilot study of 30 qualitative interviews was conducted with a new sample of

10 Spanish-speaking patients, 10 behavioral health consultants (BHCs), and 10 trained interpreters.

Quantitative results showed that interpreter use did not relate to therapeutic alliance, even when

controlling for relevant demographic variables. However, qualitative interviews suggested major themes

regarding the relative benefits and challenges of using interpreters for patients, interpreters, and BHCs.

In interviews, patients expressed a strong preference for bilingual providers. Benefits included greater

privacy, sense of trust, and accuracy of communication. However, in their absence, interpreters were seen

as increasing access to services and facilitating communication with providers, thereby addressing the

behavioral health needs of patients with limited English proficiency. BHCs and interpreters emphasized

the importance of interpreter training and a good collaborative relationship with interpreters to minimize

negative effects on the quality of care.

Keywords: integrated behavioral health care, interpreters, language concordance, limited English

proficiency, therapeutic alliance

Recently, one of the authors had a behavioral health session

with a primary care patient. The patient, a 49-year-old Hispanic

woman from Chile, had been previously seen by another be-

havioral health consultant (BHC) in the clinic. Because the

patient was fairly fluent in English, she and the previous BHC,

a monolingual English speaker, were able to communicate

without the use of an interpreter. However, when she learned

that her new BHC, a bilingual male from Mexico, spoke Span-

ish, she stated effusively how excited she was that she could use

her native language for her sessions. She stated that talking in

Spanish with her BHC was like being “en casa” [at home] and

that she could express herself more freely. Although the patient

praised her prior BHC, she noted readily that “we need more

bilingual providers” and that she could “connect” more easily

with someone who spoke her own language. In this two-part

study, we explore further language concordance between BHCs

and Spanish speaking patients.

As of 2010, the Hispanic population constituted one of the

largest ethnic minority groups in the U.S. (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, &

Albert, 2011). Spanish is the second most spoken language in the

U.S. (Shin & Kominski, 2010). This growth places an increasing

demand for language-responsive mental health services. Indeed,

language incompatibility is a structural barrier to accessing mental

health treatment for many Spanish-speaking people (Bridges, An-

drews, & Deen, 2012). Nationwide, there is a shortage of bilingual,

trained mental health providers (Annapolis Coalition on the Be-

havioral Health Workforce, 2007). Although precise figures are

not available, a search on the American Psychological Associa-

tion’s “Find a Psychologist” link revealed 6,083 therapists with a

specialization in depression but only 226 therapists nationwide

could work with primarily Spanish-speaking patients needing

treatment for depression (or 3.7% of the original 6,083 therapists;

American Psychological Association, 2015).

This article was published Online First September 7, 2015.

Bianca T. Villalobos, Ana J. Bridges, Elizabeth A. Anastasia, Carlos A.

Ojeda, Juventino Hernandez Rodriguez, and Debbie Gomez, Department

of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas.

Bridges would like to disclose that she receives fees for consultation and

supervision from Community Clinic. This project was supported by grant

D40HP19640 (PI: Ana J. Bridges) from the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services/Health Resources and Services Administration (USD-

HHS/HRSA). The authors are grateful to Arthur Andrews, Joel Berroa,

Liviu Bunaciu, Blanca Estrada, Alexis Garza, Kelly Grey, Samantha Gre-

gus, Megan Group, Araceli Mancia, Rosemary Palacios, Freddie Pastrana,

Edwin Perez, Rosie Rueda, Stacey Santos, and Edna Trejo for their

assistance with this project. The authors also thank Kathy Grisham and

Kim Shuler of Community Clinic at St. Francis House for partnering with

us in the provision and evaluation of integrated care services.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ana J.

Bridges, Department of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas,

216 Memorial Hall, Fayetteville, AR 72701. E-mail: abridges@uark.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Psychological Services © 2015 American Psychological Association

2016, Vol. 13, No. 1, 49 –59 1541-1559/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000051

49

Alliance in Spanish-Speaking Integrated Behavioral Health Care Patients

Bianca T. Villalobos, Ana J. Bridges, Elizabeth A. Anastasia, Carlos A. Ojeda,

Juventino Hernandez Rodriguez, and Debbie Gomez

University of Arkansas

The discrepancy between the growing number of Spanish speakers in the U.S. and the availability of

bilingual providers creates a barrier to accessing quality mental health care. Use of interpreters provides

one strategy for overcoming this linguistic barrier; however, concerns about whether sessions with

interpreters, versus bilingual providers, impede therapeutic alliance remain. The current study explored

associations between the use of interpreters and therapeutic alliance in a sample of 458 Spanish-speaking

patients seen for integrated behavioral health visits at primary care clinics. Patients completed a brief (4

item) therapeutic alliance scale at their behavioral health appointment. In addition, to supplement the

quantitative study data, a pilot study of 30 qualitative interviews was conducted with a new sample of

10 Spanish-speaking patients, 10 behavioral health consultants (BHCs), and 10 trained interpreters.

Quantitative results showed that interpreter use did not relate to therapeutic alliance, even when

controlling for relevant demographic variables. However, qualitative interviews suggested major themes

regarding the relative benefits and challenges of using interpreters for patients, interpreters, and BHCs.

In interviews, patients expressed a strong preference for bilingual providers. Benefits included greater

privacy, sense of trust, and accuracy of communication. However, in their absence, interpreters were seen

as increasing access to services and facilitating communication with providers, thereby addressing the

behavioral health needs of patients with limited English proficiency. BHCs and interpreters emphasized

the importance of interpreter training and a good collaborative relationship with interpreters to minimize

negative effects on the quality of care.

Keywords: integrated behavioral health care, interpreters, language concordance, limited English

proficiency, therapeutic alliance

Recently, one of the authors had a behavioral health session

with a primary care patient. The patient, a 49-year-old Hispanic

woman from Chile, had been previously seen by another be-

havioral health consultant (BHC) in the clinic. Because the

patient was fairly fluent in English, she and the previous BHC,

a monolingual English speaker, were able to communicate

without the use of an interpreter. However, when she learned

that her new BHC, a bilingual male from Mexico, spoke Span-

ish, she stated effusively how excited she was that she could use

her native language for her sessions. She stated that talking in

Spanish with her BHC was like being “en casa” [at home] and

that she could express herself more freely. Although the patient

praised her prior BHC, she noted readily that “we need more

bilingual providers” and that she could “connect” more easily

with someone who spoke her own language. In this two-part

study, we explore further language concordance between BHCs

and Spanish speaking patients.

As of 2010, the Hispanic population constituted one of the

largest ethnic minority groups in the U.S. (Ennis, Rios-Vargas, &

Albert, 2011). Spanish is the second most spoken language in the

U.S. (Shin & Kominski, 2010). This growth places an increasing

demand for language-responsive mental health services. Indeed,

language incompatibility is a structural barrier to accessing mental

health treatment for many Spanish-speaking people (Bridges, An-

drews, & Deen, 2012). Nationwide, there is a shortage of bilingual,

trained mental health providers (Annapolis Coalition on the Be-

havioral Health Workforce, 2007). Although precise figures are

not available, a search on the American Psychological Associa-

tion’s “Find a Psychologist” link revealed 6,083 therapists with a

specialization in depression but only 226 therapists nationwide

could work with primarily Spanish-speaking patients needing

treatment for depression (or 3.7% of the original 6,083 therapists;

American Psychological Association, 2015).

This article was published Online First September 7, 2015.

Bianca T. Villalobos, Ana J. Bridges, Elizabeth A. Anastasia, Carlos A.

Ojeda, Juventino Hernandez Rodriguez, and Debbie Gomez, Department

of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas.

Bridges would like to disclose that she receives fees for consultation and

supervision from Community Clinic. This project was supported by grant

D40HP19640 (PI: Ana J. Bridges) from the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services/Health Resources and Services Administration (USD-

HHS/HRSA). The authors are grateful to Arthur Andrews, Joel Berroa,

Liviu Bunaciu, Blanca Estrada, Alexis Garza, Kelly Grey, Samantha Gre-

gus, Megan Group, Araceli Mancia, Rosemary Palacios, Freddie Pastrana,

Edwin Perez, Rosie Rueda, Stacey Santos, and Edna Trejo for their

assistance with this project. The authors also thank Kathy Grisham and

Kim Shuler of Community Clinic at St. Francis House for partnering with

us in the provision and evaluation of integrated care services.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ana J.

Bridges, Department of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas,

216 Memorial Hall, Fayetteville, AR 72701. E-mail: abridges@uark.edu

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Psychological Services © 2015 American Psychological Association

2016, Vol. 13, No. 1, 49 –59 1541-1559/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000051

49

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Trained interpreters can help bridge the gap between patients’

need for Spanish-speaking services and provider availability; how-

ever, the scientific literature provides conflicting reports regarding

the value of interpreters. Positive reports note interpreters may

help patients feel understood by their therapists (Kline, Acosta,

Austin, & Johnson, 1980). Patients have indeed reported the pres-

ence of interpreters and other staff members who speak their

language is an important component of their health care (Alvarez,

Marroquin, Sandoval, & Carlson, 2014).

On the other hand, negative reports of interpreter use reveal

numerous concerns. One issue involves choosing the best inter-

preting model. The U.S. recognizes four models of interpreting

with varying perspectives about the roles of interpreters in the

provider-patient relationship (e.g., as strictly invisible messengers;

as responsible for the accuracy of information; as cultural-

linguistic ambassadors; and as cultural brokers and advocates;

Beltran Avery, 2001). Another concern is interpreter training.

Currently, there is no national or legal certification for interpreting.

Instead, major advocacy groups have developed standards of prac-

tice and ethical codes of conduct for the development of profes-

sional interpreters (for a list of advocacy groups, see Dysart-Gale,

2007). Based on terms defined by the National Council on Inter-

preting in Health Care (2001), trained interpreters are those indi-

viduals who are qualified to interpret through appropriate training

and experience and who demonstrate high proficiency in at least

two languages. Untrained interpreters, or ad hoc interpreters, are

family members, bilingual staff, or volunteers with limited to no

training in interpreting. Most research on interpreters in mental

health care, reviewed below, focuses on the issue of trained versus

untrained interpreters. Finally, potential problems may arise be-

tween the interpreter and clinician. For example, the clinician may

feel uncomfortable with or lack trust in the interpreter (Raval &

Smith, 2003).

Use of Interpreters in Primary Care and Traditional

Mental Health Settings

The primary care setting is often the entry point of an individual

patient into the health care delivery system. Primary care visits are

typically aimed at alleviating acute symptoms, managing chronic

conditions, and providing preventative care. Primary care teams

typically consist of a number of individuals who work collabora-

tively to coordinate patient care, including medical assistants,

nurses, physician assistants, general physicians, medical interpret-

ers, and, increasingly, psychologists and other behavioral health

specialists.

Given their benefit in the primary care setting (Karliner, Jacobs,

Chen, & Mutha, 2007), medical interpreters are essential members

of the health care team. On the whole, studies in the medical field

suggest visits facilitated by trained interpreters are just as satisfac-

tory as visits with bilingual providers, and both are better than

using untrained interpreters (Lee, Batal, Maselli, & Kutner, 2002;

Moreno & Morales, 2010; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2007). Studies also

suggest diagnostic conclusions are similar when physicians and

patients are language concordant or discordant (e.g., Dodd, 1984;

Farooq, Fear, & Oyebode, 1997).

When examining psychotherapeutic, versus medical, outcomes,

studies again suggest the use of trained interpreters results in

similar benefits to clients as what is obtained by seeing a bilingual

therapist. Numerous examples of the benefits of trained interpret-

ers for clients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been

reported (e.g., Brune, Eiroá-Orosa, Fischer-Ortman, Delijaj, &

Haasen, 2011; Schulz, Resick, Huber, & Griffin, 2006). On the

other hand, interpreter use may impact assessment and diagnosis.

Price and Cuellar (1981) found bilingual Mexican American pa-

tients diagnosed with schizophrenia were more likely to disclose

psychopathology symptomatology when interviewed in Spanish

than English, but Marcos, Alpert, Urcuyo, and Kesselman (1973)

found bilingual patients with schizophrenia disclosed more psy-

chopathology in English than Spanish interviews.

Several researchers discuss possible detriments to interpreter

use in therapy, primarily in terms of perceived threats to therapeu-

tic alliance (Bolton, 2002; Tribe & Tunariu, 2009). Therapeutic

alliance is the degree of involvement between the client and

therapist, as evidenced by their mutual collaboration on treatment

processes and personal rapport (Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki,

2004). Developing treatment alliance with clients who prefer to

receive clinical services in Spanish presents unique challenges. For

instance, it is possible that a Spanish-speaking client may feel

unsatisfied with a language-matched clinician who does not un-

derstand particular linguistic expressions or culturally bound be-

haviors that are specific to a region.

Very few studies have explored therapist, interpreter, and/or

client perspectives on how interpreters relate to therapeutic alli-

ance in traditional care. Kline and colleagues (1980) found twice

as many clients who used interpreters in session reported being

pleased with the services provided by mental health providers in

comparison with clients who did not use interpreters. Raval and

Smith (2003) conducted semistructured interviews with nine men-

tal health professionals regarding their experiences providing men-

tal health services to children and adolescents with the assistance

of an interpreter. Therapists expressed concern that interpreters

tend to filter out emotional content provided by clients, hampering

the therapist’s ability to share in the intensity of the client’s

experience and develop a therapeutic bond with the client. Addi-

tionally, mental health professionals perceived that techniques

intended to foster rapport with clients, such as reflective listening,

were less effective when mediated through an interpreter. Some

participants discussed experiences in which interpreters’ responses

to information shared by clients delayed the development of ther-

apeutic alliance or even damaged existing rapport (for instance, by

having an interpreter laugh at the disclosure of a client’s sexual

dysfunction). Mental health professionals also indicated challenges

related to forming a working alliance with the interpreter. Profes-

sionals reported doubting that interpreters were accurately com-

municating their statements to clients and feeling disempowered

when providing therapy with the assistance of an interpreter.

Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth, and Lopez (2005) conducted

semistructured interviews with 15 therapists and 15 interpreters in

the U.S. The authors did not specify whether interpreters had

formal training. Most therapists and interpreters ascribed value to

the alliance an interpreter forms with both therapist and client.

Most therapists reported interpreter use during sessions prolonged

the process of developing rapport with the client. Some therapists

indicated clients developed rapport more rapidly with the inter-

preter than with the therapist; a few therapists felt excluded or

competitive with the interpreter in obtaining therapeutic alliance

with the client. Several therapists reported experiences of inter-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

50 VILLALOBOS ET AL.

need for Spanish-speaking services and provider availability; how-

ever, the scientific literature provides conflicting reports regarding

the value of interpreters. Positive reports note interpreters may

help patients feel understood by their therapists (Kline, Acosta,

Austin, & Johnson, 1980). Patients have indeed reported the pres-

ence of interpreters and other staff members who speak their

language is an important component of their health care (Alvarez,

Marroquin, Sandoval, & Carlson, 2014).

On the other hand, negative reports of interpreter use reveal

numerous concerns. One issue involves choosing the best inter-

preting model. The U.S. recognizes four models of interpreting

with varying perspectives about the roles of interpreters in the

provider-patient relationship (e.g., as strictly invisible messengers;

as responsible for the accuracy of information; as cultural-

linguistic ambassadors; and as cultural brokers and advocates;

Beltran Avery, 2001). Another concern is interpreter training.

Currently, there is no national or legal certification for interpreting.

Instead, major advocacy groups have developed standards of prac-

tice and ethical codes of conduct for the development of profes-

sional interpreters (for a list of advocacy groups, see Dysart-Gale,

2007). Based on terms defined by the National Council on Inter-

preting in Health Care (2001), trained interpreters are those indi-

viduals who are qualified to interpret through appropriate training

and experience and who demonstrate high proficiency in at least

two languages. Untrained interpreters, or ad hoc interpreters, are

family members, bilingual staff, or volunteers with limited to no

training in interpreting. Most research on interpreters in mental

health care, reviewed below, focuses on the issue of trained versus

untrained interpreters. Finally, potential problems may arise be-

tween the interpreter and clinician. For example, the clinician may

feel uncomfortable with or lack trust in the interpreter (Raval &

Smith, 2003).

Use of Interpreters in Primary Care and Traditional

Mental Health Settings

The primary care setting is often the entry point of an individual

patient into the health care delivery system. Primary care visits are

typically aimed at alleviating acute symptoms, managing chronic

conditions, and providing preventative care. Primary care teams

typically consist of a number of individuals who work collabora-

tively to coordinate patient care, including medical assistants,

nurses, physician assistants, general physicians, medical interpret-

ers, and, increasingly, psychologists and other behavioral health

specialists.

Given their benefit in the primary care setting (Karliner, Jacobs,

Chen, & Mutha, 2007), medical interpreters are essential members

of the health care team. On the whole, studies in the medical field

suggest visits facilitated by trained interpreters are just as satisfac-

tory as visits with bilingual providers, and both are better than

using untrained interpreters (Lee, Batal, Maselli, & Kutner, 2002;

Moreno & Morales, 2010; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2007). Studies also

suggest diagnostic conclusions are similar when physicians and

patients are language concordant or discordant (e.g., Dodd, 1984;

Farooq, Fear, & Oyebode, 1997).

When examining psychotherapeutic, versus medical, outcomes,

studies again suggest the use of trained interpreters results in

similar benefits to clients as what is obtained by seeing a bilingual

therapist. Numerous examples of the benefits of trained interpret-

ers for clients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been

reported (e.g., Brune, Eiroá-Orosa, Fischer-Ortman, Delijaj, &

Haasen, 2011; Schulz, Resick, Huber, & Griffin, 2006). On the

other hand, interpreter use may impact assessment and diagnosis.

Price and Cuellar (1981) found bilingual Mexican American pa-

tients diagnosed with schizophrenia were more likely to disclose

psychopathology symptomatology when interviewed in Spanish

than English, but Marcos, Alpert, Urcuyo, and Kesselman (1973)

found bilingual patients with schizophrenia disclosed more psy-

chopathology in English than Spanish interviews.

Several researchers discuss possible detriments to interpreter

use in therapy, primarily in terms of perceived threats to therapeu-

tic alliance (Bolton, 2002; Tribe & Tunariu, 2009). Therapeutic

alliance is the degree of involvement between the client and

therapist, as evidenced by their mutual collaboration on treatment

processes and personal rapport (Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki,

2004). Developing treatment alliance with clients who prefer to

receive clinical services in Spanish presents unique challenges. For

instance, it is possible that a Spanish-speaking client may feel

unsatisfied with a language-matched clinician who does not un-

derstand particular linguistic expressions or culturally bound be-

haviors that are specific to a region.

Very few studies have explored therapist, interpreter, and/or

client perspectives on how interpreters relate to therapeutic alli-

ance in traditional care. Kline and colleagues (1980) found twice

as many clients who used interpreters in session reported being

pleased with the services provided by mental health providers in

comparison with clients who did not use interpreters. Raval and

Smith (2003) conducted semistructured interviews with nine men-

tal health professionals regarding their experiences providing men-

tal health services to children and adolescents with the assistance

of an interpreter. Therapists expressed concern that interpreters

tend to filter out emotional content provided by clients, hampering

the therapist’s ability to share in the intensity of the client’s

experience and develop a therapeutic bond with the client. Addi-

tionally, mental health professionals perceived that techniques

intended to foster rapport with clients, such as reflective listening,

were less effective when mediated through an interpreter. Some

participants discussed experiences in which interpreters’ responses

to information shared by clients delayed the development of ther-

apeutic alliance or even damaged existing rapport (for instance, by

having an interpreter laugh at the disclosure of a client’s sexual

dysfunction). Mental health professionals also indicated challenges

related to forming a working alliance with the interpreter. Profes-

sionals reported doubting that interpreters were accurately com-

municating their statements to clients and feeling disempowered

when providing therapy with the assistance of an interpreter.

Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth, and Lopez (2005) conducted

semistructured interviews with 15 therapists and 15 interpreters in

the U.S. The authors did not specify whether interpreters had

formal training. Most therapists and interpreters ascribed value to

the alliance an interpreter forms with both therapist and client.

Most therapists reported interpreter use during sessions prolonged

the process of developing rapport with the client. Some therapists

indicated clients developed rapport more rapidly with the inter-

preter than with the therapist; a few therapists felt excluded or

competitive with the interpreter in obtaining therapeutic alliance

with the client. Several therapists reported experiences of inter-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

50 VILLALOBOS ET AL.

preters showing resistance to interpreting certain statements for the

client (e.g., too upsetting, unnecessary information).

Ebersole (2011) conducted an empirical study to compare de-

velopment of therapeutic alliance with an interpreter or a language

concordant mental health practitioner. Social workers conducted

psychosocial interviews with parents of children who were being

evaluated for special education services in a public school district.

Results showed parents, social workers, and interpreters reported

strong therapeutic alliance in nearly every case; these findings

were consistent with qualitative information obtained from focus

groups with social workers.

In contrast to traditional therapy settings, integrated care settings

allow primary care patients with behavioral health needs opportu-

nities to be seen by mental health care professionals in the primary

care clinic, oftentimes the same day as a behavioral health need is

identified (Robinson & Reiter, 2007). Sessions with mental health

professionals who are integrated into primary care clinics tend to

be much briefer than sessions conducted in traditional mental

health care settings, both in terms of session duration (typically 15-

to 20-minute sessions) and frequency (oftentimes visits are spaced

2 or more weeks apart, with most patients receiving only 1– 4

sessions; Corso et al., 2012). This model has been shown to be

efficacious at improving the behavioral health of primary care

patients (Bryan, Morrow, & Appolonio, 2009), even in clinics

where the majority of patients are of LEP (Bridges et al., 2014).

To date, no study has examined how therapeutic alliance or

patient outcomes are affected by the use of bilingual interpreters

for primary care patients receiving behavioral health care services.

Although the research on use of interpreters in traditional mental

health care settings is instructive, the significantly compressed

time of behavioral health care visits in primary care makes gen-

eralization from traditional mental health care difficult. In addi-

tion, although research on alliance and patient outcomes in primary

care settings suggests trained interpreters are useful to patients, the

content of medical visits and of behavioral health visits may be

quite different.

Study Aims

The primary purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore

how the use of trained interpreters related to therapeutic alliance in

integrated behavioral health care patients with LEP (in particular,

with a group of Spanish speaking patients). A second purpose of

this study was to contextualize the quantitative data by providing

pilot qualitative data on how patients, behavioral health care pro-

viders, and interpreters viewed behavioral health care services

delivered through interpreters versus language-concordant provid-

ers. We expected these exploratory qualitative data would provide

a richer context for the interpretation of our quantitative analyses.

Method

Participants

Quantitative data collection. Participants were 458 Spanish-

speaking patients seen for behavioral health services at two pri-

mary care clinics, both part of a local federally qualified health

center (FQHC) in northwest Arkansas. This region has experi-

enced significant growth in its Hispanic population over the past

decade (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). The two primary care clinics

were located in cities with populations of approximately 75,000

and 60,000. The Hispanic population comprises approximately

30% to 35% of all city residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

Patients of the primary care clinics are more diverse than those of

the cities in which they are situated: more than half of patients are

Hispanic and prefer to speak a language other than English. Most

patients (more than 90%) are of lower socioeconomic status,

earning 200% or less of the Federal Poverty Level (Arkansas

Center for Health Improvement, 2015; see also http://www

.communityclinicnwa.org/). For more details about the clinics and

patients, please refer to Bridges et al. (2014).

Data were taken from consecutive patients seen over a 43-month

period (September 2010 to April 2014) who met inclusionary

criteria. Inclusionary criteria were as follows: (a) adult patient

(age ⬎17 years); (b) never received behavioral health sessions

before; (c) spoke Spanish during the behavioral health session; and

(d) completed self-report questionnaires at the conclusion of ses-

sion that included a measure of therapeutic alliance. A total of

56.6% of sessions were conducted by bilingual BHCs, whereas

43.4% of sessions were conducted with the aid of a professional

interpreter (a medical assistant trained in behavioral health inter-

pretation). Training for interpreters takes place during an in-depth

orientation to clinic services in addition to shadowing experienced

medical assistants during medical and behavioral health visits. The

length of time spent shadowing varies and depends on the medical

assistants’ comfort in their ability to function independently. Cur-

rently, the FQHC designates the use of specific interpreters for

BHCs. These BHC-specific interpreters undergo the same training,

with a special focus on ensuring confidentiality, accuracy to facil-

itate diagnoses and treatment interventions, and establishing the

role of the interpreter as a channel between the patient and clini-

cian.

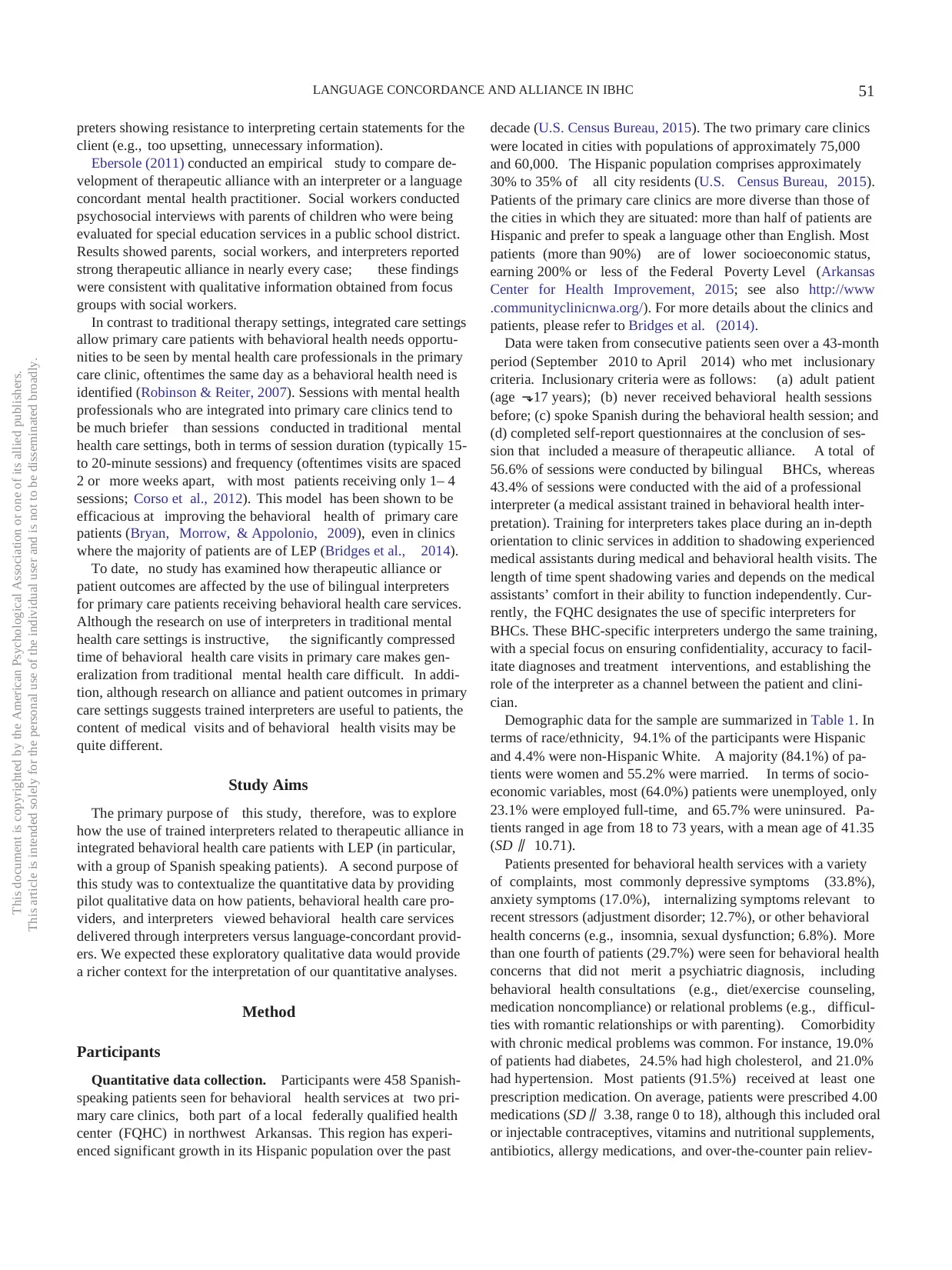

Demographic data for the sample are summarized in Table 1. In

terms of race/ethnicity, 94.1% of the participants were Hispanic

and 4.4% were non-Hispanic White. A majority (84.1%) of pa-

tients were women and 55.2% were married. In terms of socio-

economic variables, most (64.0%) patients were unemployed, only

23.1% were employed full-time, and 65.7% were uninsured. Pa-

tients ranged in age from 18 to 73 years, with a mean age of 41.35

(SD ⫽ 10.71).

Patients presented for behavioral health services with a variety

of complaints, most commonly depressive symptoms (33.8%),

anxiety symptoms (17.0%), internalizing symptoms relevant to

recent stressors (adjustment disorder; 12.7%), or other behavioral

health concerns (e.g., insomnia, sexual dysfunction; 6.8%). More

than one fourth of patients (29.7%) were seen for behavioral health

concerns that did not merit a psychiatric diagnosis, including

behavioral health consultations (e.g., diet/exercise counseling,

medication noncompliance) or relational problems (e.g., difficul-

ties with romantic relationships or with parenting). Comorbidity

with chronic medical problems was common. For instance, 19.0%

of patients had diabetes, 24.5% had high cholesterol, and 21.0%

had hypertension. Most patients (91.5%) received at least one

prescription medication. On average, patients were prescribed 4.00

medications (SD ⫽ 3.38, range 0 to 18), although this included oral

or injectable contraceptives, vitamins and nutritional supplements,

antibiotics, allergy medications, and over-the-counter pain reliev-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

51LANGUAGE CONCORDANCE AND ALLIANCE IN IBHC

client (e.g., too upsetting, unnecessary information).

Ebersole (2011) conducted an empirical study to compare de-

velopment of therapeutic alliance with an interpreter or a language

concordant mental health practitioner. Social workers conducted

psychosocial interviews with parents of children who were being

evaluated for special education services in a public school district.

Results showed parents, social workers, and interpreters reported

strong therapeutic alliance in nearly every case; these findings

were consistent with qualitative information obtained from focus

groups with social workers.

In contrast to traditional therapy settings, integrated care settings

allow primary care patients with behavioral health needs opportu-

nities to be seen by mental health care professionals in the primary

care clinic, oftentimes the same day as a behavioral health need is

identified (Robinson & Reiter, 2007). Sessions with mental health

professionals who are integrated into primary care clinics tend to

be much briefer than sessions conducted in traditional mental

health care settings, both in terms of session duration (typically 15-

to 20-minute sessions) and frequency (oftentimes visits are spaced

2 or more weeks apart, with most patients receiving only 1– 4

sessions; Corso et al., 2012). This model has been shown to be

efficacious at improving the behavioral health of primary care

patients (Bryan, Morrow, & Appolonio, 2009), even in clinics

where the majority of patients are of LEP (Bridges et al., 2014).

To date, no study has examined how therapeutic alliance or

patient outcomes are affected by the use of bilingual interpreters

for primary care patients receiving behavioral health care services.

Although the research on use of interpreters in traditional mental

health care settings is instructive, the significantly compressed

time of behavioral health care visits in primary care makes gen-

eralization from traditional mental health care difficult. In addi-

tion, although research on alliance and patient outcomes in primary

care settings suggests trained interpreters are useful to patients, the

content of medical visits and of behavioral health visits may be

quite different.

Study Aims

The primary purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore

how the use of trained interpreters related to therapeutic alliance in

integrated behavioral health care patients with LEP (in particular,

with a group of Spanish speaking patients). A second purpose of

this study was to contextualize the quantitative data by providing

pilot qualitative data on how patients, behavioral health care pro-

viders, and interpreters viewed behavioral health care services

delivered through interpreters versus language-concordant provid-

ers. We expected these exploratory qualitative data would provide

a richer context for the interpretation of our quantitative analyses.

Method

Participants

Quantitative data collection. Participants were 458 Spanish-

speaking patients seen for behavioral health services at two pri-

mary care clinics, both part of a local federally qualified health

center (FQHC) in northwest Arkansas. This region has experi-

enced significant growth in its Hispanic population over the past

decade (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). The two primary care clinics

were located in cities with populations of approximately 75,000

and 60,000. The Hispanic population comprises approximately

30% to 35% of all city residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).

Patients of the primary care clinics are more diverse than those of

the cities in which they are situated: more than half of patients are

Hispanic and prefer to speak a language other than English. Most

patients (more than 90%) are of lower socioeconomic status,

earning 200% or less of the Federal Poverty Level (Arkansas

Center for Health Improvement, 2015; see also http://www

.communityclinicnwa.org/). For more details about the clinics and

patients, please refer to Bridges et al. (2014).

Data were taken from consecutive patients seen over a 43-month

period (September 2010 to April 2014) who met inclusionary

criteria. Inclusionary criteria were as follows: (a) adult patient

(age ⬎17 years); (b) never received behavioral health sessions

before; (c) spoke Spanish during the behavioral health session; and

(d) completed self-report questionnaires at the conclusion of ses-

sion that included a measure of therapeutic alliance. A total of

56.6% of sessions were conducted by bilingual BHCs, whereas

43.4% of sessions were conducted with the aid of a professional

interpreter (a medical assistant trained in behavioral health inter-

pretation). Training for interpreters takes place during an in-depth

orientation to clinic services in addition to shadowing experienced

medical assistants during medical and behavioral health visits. The

length of time spent shadowing varies and depends on the medical

assistants’ comfort in their ability to function independently. Cur-

rently, the FQHC designates the use of specific interpreters for

BHCs. These BHC-specific interpreters undergo the same training,

with a special focus on ensuring confidentiality, accuracy to facil-

itate diagnoses and treatment interventions, and establishing the

role of the interpreter as a channel between the patient and clini-

cian.

Demographic data for the sample are summarized in Table 1. In

terms of race/ethnicity, 94.1% of the participants were Hispanic

and 4.4% were non-Hispanic White. A majority (84.1%) of pa-

tients were women and 55.2% were married. In terms of socio-

economic variables, most (64.0%) patients were unemployed, only

23.1% were employed full-time, and 65.7% were uninsured. Pa-

tients ranged in age from 18 to 73 years, with a mean age of 41.35

(SD ⫽ 10.71).

Patients presented for behavioral health services with a variety

of complaints, most commonly depressive symptoms (33.8%),

anxiety symptoms (17.0%), internalizing symptoms relevant to

recent stressors (adjustment disorder; 12.7%), or other behavioral

health concerns (e.g., insomnia, sexual dysfunction; 6.8%). More

than one fourth of patients (29.7%) were seen for behavioral health

concerns that did not merit a psychiatric diagnosis, including

behavioral health consultations (e.g., diet/exercise counseling,

medication noncompliance) or relational problems (e.g., difficul-

ties with romantic relationships or with parenting). Comorbidity

with chronic medical problems was common. For instance, 19.0%

of patients had diabetes, 24.5% had high cholesterol, and 21.0%

had hypertension. Most patients (91.5%) received at least one

prescription medication. On average, patients were prescribed 4.00

medications (SD ⫽ 3.38, range 0 to 18), although this included oral

or injectable contraceptives, vitamins and nutritional supplements,

antibiotics, allergy medications, and over-the-counter pain reliev-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

51LANGUAGE CONCORDANCE AND ALLIANCE IN IBHC

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ers. A total of 27.7% of patients were prescribed a psychotropic

medication.

Qualitative data collection. Following the analyses of our

quantitative data, we opted to conduct an exploratory pilot quali-

tative study that would permit richer context for our quantitative

study. Ten new Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients who had not

participated in the quantitative study (70% female; M age ⫽ 38.30

years, SD ⫽ 6.77, range ⫽ 29 –50), 10 behavioral health care

providers (60% female; 40% Hispanic; M age ⫽ 29.20 years, SD ⫽

5.60, range ⫽ 25– 44), and 10 medical assistants (80% female;

100% Hispanic; M age ⫽ 25.80 years, SD ⫽ 4.61, range ⫽ 22–36)

who had served as trained interpreters in behavioral health ap-

pointments were recruited to provide qualitative information about

their experiences with therapeutic alliance. Of the Spanish-

speaking patients, half (n ⫽ 5) reported on a session in which they

had used an interpreter and half (n ⫽ 5) reported on a session in

which they had seen a bilingual BHC. Of the BHCs, 1 was a native

Spanish speaker, 5 spoke Spanish fluently as a second language,

and 4 used an interpreter when working with Spanish-speaking

patients. BHCs had an average of 5.90 years of general clinical

experience (SD ⫽ 5.62, range ⫽ 2–21) and 1.94 years of experi-

ence in integrated behavioral health care (SD ⫽ 1.66, range ⫽ 5

weeks to 6 years). Of the trained interpreters, all were native

Spanish speakers. Interpreters had an average of 4.42 years work-

ing as interpreters (SD ⫽ 2.57, range ⫽ 8 months to 7 years).

Measures

Demographic data. We culled preexisting information from

patient electronic medical records, including demographic vari-

ables (age, ethnicity, race, marital status, employment status, in-

surance status, and primary language). We also obtained dates of

BHC appointments, global assessment of functioning (GAF)

scores given at each BHC appointment, and medical and psychi-

atric diagnoses from electronic records.

Psychiatric distress. To assess patient symptoms and func-

tional impairment, the A Collaborative Outcomes Resource Net-

work (ACORN) questionnaire was utilized (Brown, 2011). The

18-item ACORN assesses global levels of psychiatric symptoms.

The adult version (for people 18 years or older) asks questions

about mood, anxiety, sleep, alcohol and drug use, and functional

impairment. Items inquire about how often the person has expe-

rienced each of the symptoms in the past two weeks. Responses are

scored on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

Items are then averaged to form a global score. According to the

ACORN manual, Cronbach’s alpha for the global distress items is

.92 in clinical samples. Concurrent validity was demonstrated with

a significant relation between ACORN global distress scores and

the Beck Depression Inventory (r ⫽ .78).

Therapeutic alliance. In the ACORN, there are four ques-

tions assessing therapeutic alliance, also scored on a 5-point Likert

scale (from 0 ⫽ do not agree to 4 ⫽ agree). Items assess the

relevance of the information discussed during the behavioral

health visit for the patient and the patient’s perceptions of the

working relationship with the behavioral health consultant. These

four items are averaged to form a session alliance score, with

higher scores indicating higher alliance. In the current study,

internal consistency reliability was good, Cronbach’s alpha ⫽ .80.

In qualitative interviews conducted by the study authors,

Spanish-speaking patients, behavioral health care providers, and

medical assistants who had served as interpreters were asked a few

open-ended questions about their perceptions of the influence of

using an interpreter or receiving services from a bilingual behav-

ioral health care provider on therapeutic alliance. Table 2 provides

a list of questions asked of each participant group.

Procedures

A sequential exploratory mixed-methods design was used, such

that after quantitative data were collected and analyzed, qualitative

data were collected to facilitate a more enriched interpretation of

the results (Hanson, Creswell, Clark, Petska, & Creswell, 2005).

The qualitative pilot study, in particular, was designed to enrich

our understanding of the topic by providing an initial exploration

into categories that represent the myriad benefits and challenges of

utilizing interpreters in behavioral health sessions conducted in

primary care settings. All procedures were approved by the exec-

Table 1

Patient Demographic Information

Variable M SD N %

Gender

Male 73 15.9%

Female 385 84.1%

Age, in years 41.35 10.71

Marital status

Single 122 26.6%

Married 253 55.2%

Divorced or separated 30 6.5%

Widowed 7 1.5%

Other 46 10.0%

Employment status

Employed full-time 106 23.1%

Employed part-time 40 8.7%

Unemployed 293 64.0%

Retired 2 .4%

Other 17 3.7%

Race/ethnicity

Hispanic 431 94.1%

Non-Hispanic White 20 4.4%

Insurance coverage

Public insurance 75 16.4%

Private insurance 53 11.6%

Other insurance 29 6.3%

Uninsured 301 65.7%

Chronic health condition

Diabetes 87 19.0%

High cholesterol 112 24.5%

Hypertension 96 21.0%

Mental health condition

Depressive disorder 155 33.8%

Anxiety disorder 78 17.0%

Adjustment disorder 58 12.7%

Other 31 6.8%

Patient is prescribed medication 419 91.5%

Number of prescription medications 4.00 3.38

Patient is prescribed psychotropic

medication 127 27.7%

Prior year clinic encounters 5.40 4.07

ACORN Global Distress 1.98 .84

Interpreter used during behavioral

health session 199 43.4%

ACORN therapeutic alliance 3.87 .32

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

52 VILLALOBOS ET AL.

medication.

Qualitative data collection. Following the analyses of our

quantitative data, we opted to conduct an exploratory pilot quali-

tative study that would permit richer context for our quantitative

study. Ten new Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients who had not

participated in the quantitative study (70% female; M age ⫽ 38.30

years, SD ⫽ 6.77, range ⫽ 29 –50), 10 behavioral health care

providers (60% female; 40% Hispanic; M age ⫽ 29.20 years, SD ⫽

5.60, range ⫽ 25– 44), and 10 medical assistants (80% female;

100% Hispanic; M age ⫽ 25.80 years, SD ⫽ 4.61, range ⫽ 22–36)

who had served as trained interpreters in behavioral health ap-

pointments were recruited to provide qualitative information about

their experiences with therapeutic alliance. Of the Spanish-

speaking patients, half (n ⫽ 5) reported on a session in which they

had used an interpreter and half (n ⫽ 5) reported on a session in

which they had seen a bilingual BHC. Of the BHCs, 1 was a native

Spanish speaker, 5 spoke Spanish fluently as a second language,

and 4 used an interpreter when working with Spanish-speaking

patients. BHCs had an average of 5.90 years of general clinical

experience (SD ⫽ 5.62, range ⫽ 2–21) and 1.94 years of experi-

ence in integrated behavioral health care (SD ⫽ 1.66, range ⫽ 5

weeks to 6 years). Of the trained interpreters, all were native

Spanish speakers. Interpreters had an average of 4.42 years work-

ing as interpreters (SD ⫽ 2.57, range ⫽ 8 months to 7 years).

Measures

Demographic data. We culled preexisting information from

patient electronic medical records, including demographic vari-

ables (age, ethnicity, race, marital status, employment status, in-

surance status, and primary language). We also obtained dates of

BHC appointments, global assessment of functioning (GAF)

scores given at each BHC appointment, and medical and psychi-

atric diagnoses from electronic records.

Psychiatric distress. To assess patient symptoms and func-

tional impairment, the A Collaborative Outcomes Resource Net-

work (ACORN) questionnaire was utilized (Brown, 2011). The

18-item ACORN assesses global levels of psychiatric symptoms.

The adult version (for people 18 years or older) asks questions

about mood, anxiety, sleep, alcohol and drug use, and functional

impairment. Items inquire about how often the person has expe-

rienced each of the symptoms in the past two weeks. Responses are

scored on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

Items are then averaged to form a global score. According to the

ACORN manual, Cronbach’s alpha for the global distress items is

.92 in clinical samples. Concurrent validity was demonstrated with

a significant relation between ACORN global distress scores and

the Beck Depression Inventory (r ⫽ .78).

Therapeutic alliance. In the ACORN, there are four ques-

tions assessing therapeutic alliance, also scored on a 5-point Likert

scale (from 0 ⫽ do not agree to 4 ⫽ agree). Items assess the

relevance of the information discussed during the behavioral

health visit for the patient and the patient’s perceptions of the

working relationship with the behavioral health consultant. These

four items are averaged to form a session alliance score, with

higher scores indicating higher alliance. In the current study,

internal consistency reliability was good, Cronbach’s alpha ⫽ .80.

In qualitative interviews conducted by the study authors,

Spanish-speaking patients, behavioral health care providers, and

medical assistants who had served as interpreters were asked a few

open-ended questions about their perceptions of the influence of

using an interpreter or receiving services from a bilingual behav-

ioral health care provider on therapeutic alliance. Table 2 provides

a list of questions asked of each participant group.

Procedures

A sequential exploratory mixed-methods design was used, such

that after quantitative data were collected and analyzed, qualitative

data were collected to facilitate a more enriched interpretation of

the results (Hanson, Creswell, Clark, Petska, & Creswell, 2005).

The qualitative pilot study, in particular, was designed to enrich

our understanding of the topic by providing an initial exploration

into categories that represent the myriad benefits and challenges of

utilizing interpreters in behavioral health sessions conducted in

primary care settings. All procedures were approved by the exec-

Table 1

Patient Demographic Information

Variable M SD N %

Gender

Male 73 15.9%

Female 385 84.1%

Age, in years 41.35 10.71

Marital status

Single 122 26.6%

Married 253 55.2%

Divorced or separated 30 6.5%

Widowed 7 1.5%

Other 46 10.0%

Employment status

Employed full-time 106 23.1%

Employed part-time 40 8.7%

Unemployed 293 64.0%

Retired 2 .4%

Other 17 3.7%

Race/ethnicity

Hispanic 431 94.1%

Non-Hispanic White 20 4.4%

Insurance coverage

Public insurance 75 16.4%

Private insurance 53 11.6%

Other insurance 29 6.3%

Uninsured 301 65.7%

Chronic health condition

Diabetes 87 19.0%

High cholesterol 112 24.5%

Hypertension 96 21.0%

Mental health condition

Depressive disorder 155 33.8%

Anxiety disorder 78 17.0%

Adjustment disorder 58 12.7%

Other 31 6.8%

Patient is prescribed medication 419 91.5%

Number of prescription medications 4.00 3.38

Patient is prescribed psychotropic

medication 127 27.7%

Prior year clinic encounters 5.40 4.07

ACORN Global Distress 1.98 .84

Interpreter used during behavioral

health session 199 43.4%

ACORN therapeutic alliance 3.87 .32

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

52 VILLALOBOS ET AL.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

utive director of the FQHC and the university’s Institutional Re-

view Board.

Quantitative data collection. Patients presented to their pri-

mary care provider for a variety of reasons, including annual

physical examinations, infections, pain, diabetes management, and

asthma. During their visit, the primary care provider identified a

behavioral health issue and referred the patient to a behavioral

health consultant for a same-day appointment. Behavioral health

consultants were licensed clinical social workers (n ⫽ 5), a li-

censed psychologist (n ⫽ 1), or psychology doctoral students in

training (n ⫽ 6). At that visit and all subsequent behavioral health

appointments, patients were instructed to complete the ACORN

questionnaire. Patients were seen for an average of 1.53 visits

(SD ⫽ 1.00, range 1– 8). Each visit lasted between 15 and 30

minutes and visits were spaced approximately 2 to 4 weeks apart.

Sessions were problem-focused and generally employed brief

cognitive– behavioral interventions such as behavioral activation,

motivational enhancement, exposure therapy, and psychoeduca-

tion. As part of standard operating procedures, patients of the

FQHC sign a consent form that specifies information in their

medical chart may be used for research purposes. Therefore,

additional consent to access preexisting data from electronic med-

ical records for this part of the study was not requested from

patients.

Qualitative data collection. Qualitative data collection took

place over a 2-month span (mid-September through mid-

November 2014). During times when research assistants were

present at the primary care sites, behavioral health care providers

having sessions with Spanish-speaking patients would request the

patient’s permission to allow a researcher to ask them a few

open-ended questions at the end of their appointment. Patients

were not selected by any other criteria. In addition, during that

span of time researchers arranged in-person or telephone inter-

views with behavioral health care providers and medical assistants.

We interviewed all BHCs who were currently employed by the

clinic (n ⫽ 4) and all BHCs who were or had completed an

externship at the clinic as part of their doctoral training (n ⫽ 6).

We also solicited interviews with medical assistants who were

currently employed by the clinic, frequently provided interpreta-

tion services for BHCs, and could schedule an interview.

All participants provided verbal consent and received a copy of

a consent form describing the purpose of the study, procedures,

and how data would be utilized. Interviews were conducted in

Spanish by bilingual clinical psychology doctoral students and a

licensed psychologist (all study authors). Interviews lasted be-

tween five and 10 minutes each. Interview responses were typed

out verbatim by the interviewer. Qualitative interview responses

were then content analyzed by the researchers for identification of

emerging themes. The process of identifying thematic categories

involved reading through interview transcripts, identifying as a

group the themes reflected in the responses, and then detailing

these themes into a codebook. Because of the exploratory nature of

the study, we avoided collapsing categories and opted instead to

create independent categories for all identified themes. Following

creation of the codebook, the first two authors independently

coded each interview. We assessed intercoder reliability separately

for each sample, using percent agreement (total agreements/total

coding instances). Interrater reliabilities were 97% (patient data),

86% (behavioral health provider data), and 92% (medical assistant

data). Disagreements were resolved via consensus by the two

coders.

Results

Quantitative Results

A one-way between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted to determine whether the use of an interpreter in the

behavioral health session (yes/no) was related to patients’ self-

reported therapeutic alliance with the behavioral health consultant.

No significant main effect of interpreter use was found, F(1,

456) ⫽ 1.81, p ⫽ .179. Patients who had an interpreter in the room

(M ⫽ 3.89, SD ⫽ 0.32, N ⫽ 199) had alliance ratings comparable

to those of patients who received services from a bilingual BHC

(M ⫽ 3.85, SD ⫽ 0.32, N ⫽ 259). Even when controlling for

relevant demographic covariates in a multiple regression (see

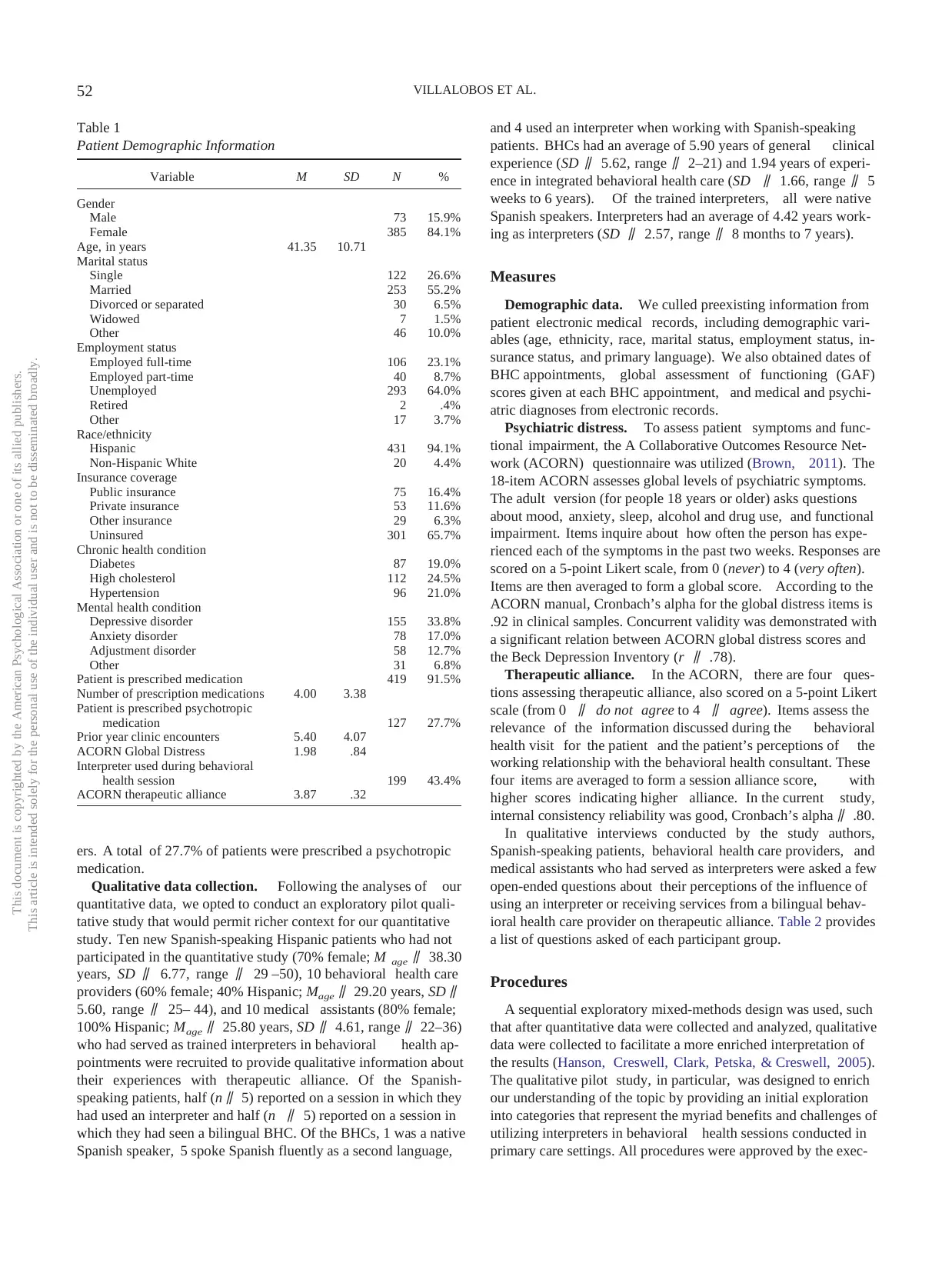

Table 2

Qualitative Interview Questions

Group Questions

Patients 1. How was your visit with [name of BHC]?

2. What did you think of the Spanish speaking abilities of [name of bilingual BHC or name of interpreter]? Was it

easy to understand his/her Spanish?

3. How well do you think [name of bilingual BHC or name of interpreter] understood your Spanish?

4. Do you think you had a good relationship with [name of BHC]?

5. Do you think it made that a difference that [name of BHC] could/could not speak Spanish?

6. Had you used an interpreter before?

7. For sessions with bilingual BHCs: Would it have been preferable to have an interpreter in your visit with [name

of bilingual BHC]? Why or why not?

8. For sessions with interpreters: Would it have been preferable if [name of BHC] spoke Spanish? Why or why not?

9. We want to improve our services for Spanish speaking patients. What could we do to make our services better?

Interpreters 1. What is your experience like providing interpreter services for Spanish speaking patients of the clinic?

2. Are these experiences similar for medical visits and behavioral health visits? If not, what is different?

3. How do you think the quality of patient care is affected by interpreter services?

BHCs 1. What is your experience like providing bilingual services for Spanish speaking patients of the clinic?

2. What about using interpreter services (if applicable)—how have you found that to be?

3. How do you think the quality of patient care is affected by interpreter services?

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

53LANGUAGE CONCORDANCE AND ALLIANCE IN IBHC

view Board.

Quantitative data collection. Patients presented to their pri-

mary care provider for a variety of reasons, including annual

physical examinations, infections, pain, diabetes management, and

asthma. During their visit, the primary care provider identified a

behavioral health issue and referred the patient to a behavioral

health consultant for a same-day appointment. Behavioral health

consultants were licensed clinical social workers (n ⫽ 5), a li-

censed psychologist (n ⫽ 1), or psychology doctoral students in

training (n ⫽ 6). At that visit and all subsequent behavioral health

appointments, patients were instructed to complete the ACORN

questionnaire. Patients were seen for an average of 1.53 visits

(SD ⫽ 1.00, range 1– 8). Each visit lasted between 15 and 30

minutes and visits were spaced approximately 2 to 4 weeks apart.

Sessions were problem-focused and generally employed brief

cognitive– behavioral interventions such as behavioral activation,

motivational enhancement, exposure therapy, and psychoeduca-

tion. As part of standard operating procedures, patients of the

FQHC sign a consent form that specifies information in their

medical chart may be used for research purposes. Therefore,

additional consent to access preexisting data from electronic med-

ical records for this part of the study was not requested from

patients.

Qualitative data collection. Qualitative data collection took

place over a 2-month span (mid-September through mid-

November 2014). During times when research assistants were

present at the primary care sites, behavioral health care providers

having sessions with Spanish-speaking patients would request the

patient’s permission to allow a researcher to ask them a few

open-ended questions at the end of their appointment. Patients

were not selected by any other criteria. In addition, during that

span of time researchers arranged in-person or telephone inter-

views with behavioral health care providers and medical assistants.

We interviewed all BHCs who were currently employed by the

clinic (n ⫽ 4) and all BHCs who were or had completed an

externship at the clinic as part of their doctoral training (n ⫽ 6).

We also solicited interviews with medical assistants who were

currently employed by the clinic, frequently provided interpreta-

tion services for BHCs, and could schedule an interview.

All participants provided verbal consent and received a copy of

a consent form describing the purpose of the study, procedures,

and how data would be utilized. Interviews were conducted in

Spanish by bilingual clinical psychology doctoral students and a

licensed psychologist (all study authors). Interviews lasted be-

tween five and 10 minutes each. Interview responses were typed

out verbatim by the interviewer. Qualitative interview responses

were then content analyzed by the researchers for identification of

emerging themes. The process of identifying thematic categories

involved reading through interview transcripts, identifying as a

group the themes reflected in the responses, and then detailing

these themes into a codebook. Because of the exploratory nature of

the study, we avoided collapsing categories and opted instead to

create independent categories for all identified themes. Following

creation of the codebook, the first two authors independently

coded each interview. We assessed intercoder reliability separately

for each sample, using percent agreement (total agreements/total

coding instances). Interrater reliabilities were 97% (patient data),

86% (behavioral health provider data), and 92% (medical assistant

data). Disagreements were resolved via consensus by the two

coders.

Results

Quantitative Results

A one-way between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted to determine whether the use of an interpreter in the

behavioral health session (yes/no) was related to patients’ self-

reported therapeutic alliance with the behavioral health consultant.

No significant main effect of interpreter use was found, F(1,

456) ⫽ 1.81, p ⫽ .179. Patients who had an interpreter in the room

(M ⫽ 3.89, SD ⫽ 0.32, N ⫽ 199) had alliance ratings comparable

to those of patients who received services from a bilingual BHC

(M ⫽ 3.85, SD ⫽ 0.32, N ⫽ 259). Even when controlling for

relevant demographic covariates in a multiple regression (see

Table 2

Qualitative Interview Questions

Group Questions

Patients 1. How was your visit with [name of BHC]?

2. What did you think of the Spanish speaking abilities of [name of bilingual BHC or name of interpreter]? Was it

easy to understand his/her Spanish?

3. How well do you think [name of bilingual BHC or name of interpreter] understood your Spanish?

4. Do you think you had a good relationship with [name of BHC]?

5. Do you think it made that a difference that [name of BHC] could/could not speak Spanish?

6. Had you used an interpreter before?

7. For sessions with bilingual BHCs: Would it have been preferable to have an interpreter in your visit with [name

of bilingual BHC]? Why or why not?

8. For sessions with interpreters: Would it have been preferable if [name of BHC] spoke Spanish? Why or why not?

9. We want to improve our services for Spanish speaking patients. What could we do to make our services better?

Interpreters 1. What is your experience like providing interpreter services for Spanish speaking patients of the clinic?

2. Are these experiences similar for medical visits and behavioral health visits? If not, what is different?

3. How do you think the quality of patient care is affected by interpreter services?

BHCs 1. What is your experience like providing bilingual services for Spanish speaking patients of the clinic?

2. What about using interpreter services (if applicable)—how have you found that to be?

3. How do you think the quality of patient care is affected by interpreter services?

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

53LANGUAGE CONCORDANCE AND ALLIANCE IN IBHC

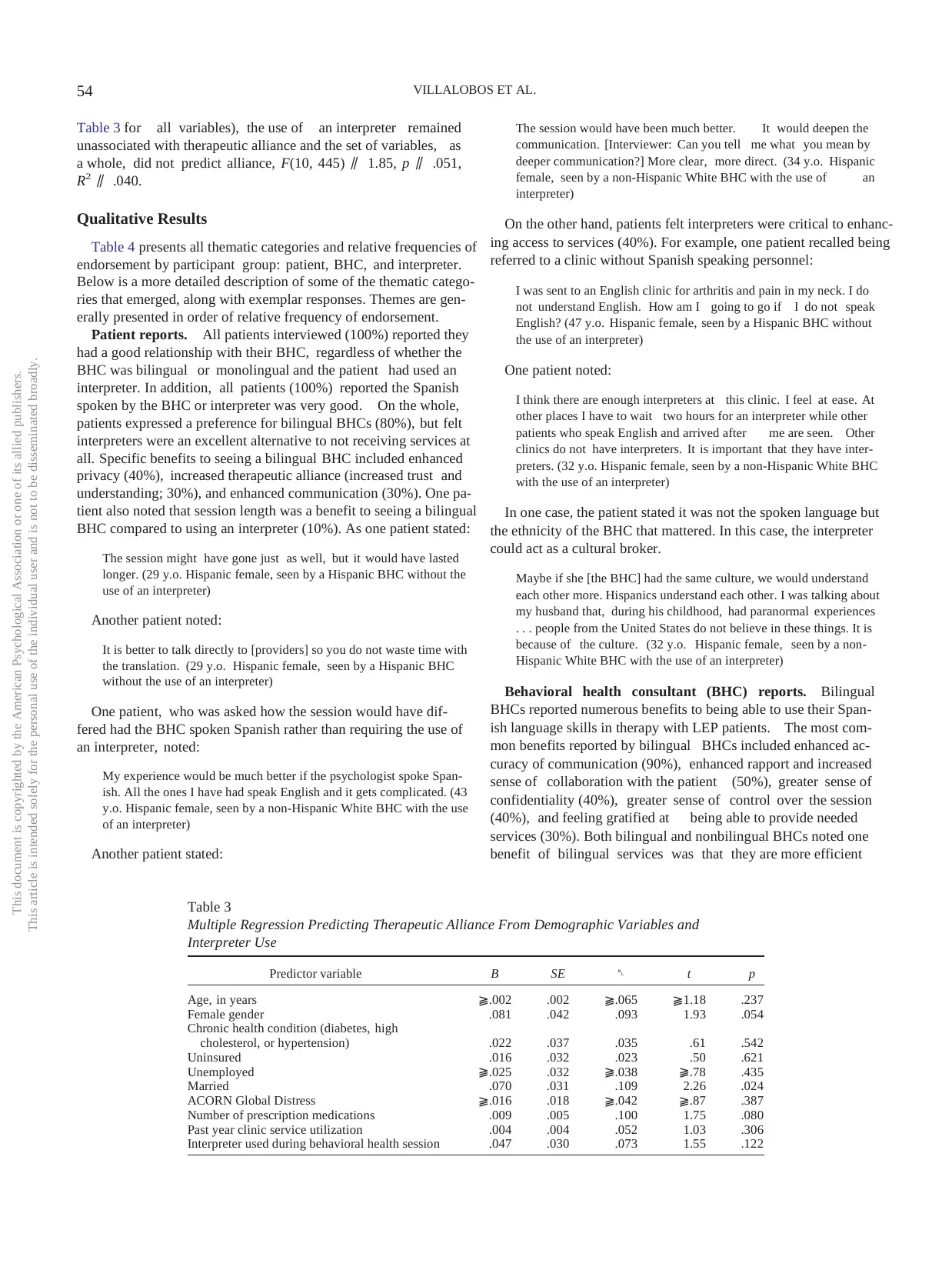

Table 3 for all variables), the use of an interpreter remained

unassociated with therapeutic alliance and the set of variables, as

a whole, did not predict alliance, F(10, 445) ⫽ 1.85, p ⫽ .051,

R 2 ⫽ .040.

Qualitative Results

Table 4 presents all thematic categories and relative frequencies of

endorsement by participant group: patient, BHC, and interpreter.

Below is a more detailed description of some of the thematic catego-

ries that emerged, along with exemplar responses. Themes are gen-

erally presented in order of relative frequency of endorsement.

Patient reports. All patients interviewed (100%) reported they

had a good relationship with their BHC, regardless of whether the

BHC was bilingual or monolingual and the patient had used an

interpreter. In addition, all patients (100%) reported the Spanish

spoken by the BHC or interpreter was very good. On the whole,

patients expressed a preference for bilingual BHCs (80%), but felt

interpreters were an excellent alternative to not receiving services at

all. Specific benefits to seeing a bilingual BHC included enhanced

privacy (40%), increased therapeutic alliance (increased trust and

understanding; 30%), and enhanced communication (30%). One pa-

tient also noted that session length was a benefit to seeing a bilingual

BHC compared to using an interpreter (10%). As one patient stated:

The session might have gone just as well, but it would have lasted

longer. (29 y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a Hispanic BHC without the

use of an interpreter)

Another patient noted:

It is better to talk directly to [providers] so you do not waste time with

the translation. (29 y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a Hispanic BHC

without the use of an interpreter)

One patient, who was asked how the session would have dif-

fered had the BHC spoken Spanish rather than requiring the use of

an interpreter, noted:

My experience would be much better if the psychologist spoke Span-

ish. All the ones I have had speak English and it gets complicated. (43

y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a non-Hispanic White BHC with the use

of an interpreter)

Another patient stated:

The session would have been much better. It would deepen the

communication. [Interviewer: Can you tell me what you mean by

deeper communication?] More clear, more direct. (34 y.o. Hispanic

female, seen by a non-Hispanic White BHC with the use of an

interpreter)

On the other hand, patients felt interpreters were critical to enhanc-

ing access to services (40%). For example, one patient recalled being

referred to a clinic without Spanish speaking personnel:

I was sent to an English clinic for arthritis and pain in my neck. I do

not understand English. How am I going to go if I do not speak

English? (47 y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a Hispanic BHC without

the use of an interpreter)

One patient noted:

I think there are enough interpreters at this clinic. I feel at ease. At

other places I have to wait two hours for an interpreter while other

patients who speak English and arrived after me are seen. Other

clinics do not have interpreters. It is important that they have inter-

preters. (32 y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a non-Hispanic White BHC

with the use of an interpreter)

In one case, the patient stated it was not the spoken language but

the ethnicity of the BHC that mattered. In this case, the interpreter

could act as a cultural broker.

Maybe if she [the BHC] had the same culture, we would understand

each other more. Hispanics understand each other. I was talking about

my husband that, during his childhood, had paranormal experiences

. . . people from the United States do not believe in these things. It is

because of the culture. (32 y.o. Hispanic female, seen by a non-

Hispanic White BHC with the use of an interpreter)

Behavioral health consultant (BHC) reports. Bilingual

BHCs reported numerous benefits to being able to use their Span-

ish language skills in therapy with LEP patients. The most com-

mon benefits reported by bilingual BHCs included enhanced ac-

curacy of communication (90%), enhanced rapport and increased

sense of collaboration with the patient (50%), greater sense of

confidentiality (40%), greater sense of control over the session

(40%), and feeling gratified at being able to provide needed

services (30%). Both bilingual and nonbilingual BHCs noted one

benefit of bilingual services was that they are more efficient

Table 3

Multiple Regression Predicting Therapeutic Alliance From Demographic Variables and

Interpreter Use

Predictor variable B SE  t p

Age, in years ⫺.002 .002 ⫺.065 ⫺1.18 .237

Female gender .081 .042 .093 1.93 .054

Chronic health condition (diabetes, high

cholesterol, or hypertension) .022 .037 .035 .61 .542

Uninsured .016 .032 .023 .50 .621

Unemployed ⫺.025 .032 ⫺.038 ⫺.78 .435

Married .070 .031 .109 2.26 .024

ACORN Global Distress ⫺.016 .018 ⫺.042 ⫺.87 .387

Number of prescription medications .009 .005 .100 1.75 .080

Past year clinic service utilization .004 .004 .052 1.03 .306

Interpreter used during behavioral health session .047 .030 .073 1.55 .122

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

54 VILLALOBOS ET AL.

unassociated with therapeutic alliance and the set of variables, as

a whole, did not predict alliance, F(10, 445) ⫽ 1.85, p ⫽ .051,

R 2 ⫽ .040.

Qualitative Results

Table 4 presents all thematic categories and relative frequencies of

endorsement by participant group: patient, BHC, and interpreter.

Below is a more detailed description of some of the thematic catego-

ries that emerged, along with exemplar responses. Themes are gen-

erally presented in order of relative frequency of endorsement.

Patient reports. All patients interviewed (100%) reported they

had a good relationship with their BHC, regardless of whether the

BHC was bilingual or monolingual and the patient had used an

interpreter. In addition, all patients (100%) reported the Spanish

spoken by the BHC or interpreter was very good. On the whole,

patients expressed a preference for bilingual BHCs (80%), but felt

interpreters were an excellent alternative to not receiving services at

all. Specific benefits to seeing a bilingual BHC included enhanced

privacy (40%), increased therapeutic alliance (increased trust and