Rapport: A key to treatment success

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/23

|4

|3045

|333

AI Summary

The text you provided appears to be the beginning of an article by Matthew J. Leach on the importance of rapport in treatment success. The article highlights the effects that strong therapeutic relationships may have on patient satisfaction, treatment compliance, and client outcomes. The article defines terms such as therapeutic alliance, therapeutic relationship, and patient rapport and discusses their importance in achieving positive client outcomes. The article also presents evidence from studies that support the association between good rapport and positive client outcomes. Is there anything specific you would like me to summarize or explain further?

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice (2005) 11, 262–265

Rapport: A key to treatment success

Matthew J. Leach

School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia, North Terrace Adelaide SA 5000, South Australia

Summary The therapeutic relationship isa concept often ignored in current

literature. As such, the importance of good patient rapport may be overlooked. To

addressthese concerns,the following paperhighlightsthe effects that strong

therapeutic relationships may have on patient satisfaction, treatment compliance

and client outcomes.Strategiesthat practitionerscan employ to facilitate the

development of good patient rapport are also discussed.

& 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The first and most important objective of any

client–practitioner interaction is the establishment

of client rapport. Aside from facilitating commu-

nication between the practitioner and patient,

good patient rapport may also improve client

assessmentand the achievementof expected

treatmentoutcomes.1 Nonetheless,development

of the therapeutic relationship requires time and

skill.2 As the therapist’s contribution to this

alliance is often overlooked in the literature,3 the

purpose of this paper is to enlighten readers of the

importance of establishing a strong therapeutic

relationship with their clients, and to provide

practitionerswith useful strategiesto improve

client rapport in clinical practice. These skills

may also facilitate a practitioner’s ability to

develop effective working relationships with other

health care providers.4 Firstly however, an explora-

tion of the terms used to describe the therapeutic

relationship willallow readers to understand the

context in which this paper is situated.

Definitions

Many terms exist which describe the bond between

a client and practitioner. The terms most fre-

quently identified in the literature are therapeutic

alliance, therapeutic relationship and patient rap-

port. By definition, a therapeutic alliance is a

‘yconscious and active collaboration between the

patient and therapist’.3 Similarly,a therapeutic

relationship is ‘a trusting connection and rapport

established between therapist and client through

collaboration,communication,therapist empathy

and mutual understanding and respect’.4 Likewise,

patient rapport is defined as a ‘harmonious rela-

tionship’.5 As each of these terms incorporate

similar underlying themes, including collaboration,

reciprocality, parity and growth, these terms are

considered interchangeable.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/ctnm

KEYWORDS

Rapport;

Therapeutic

alliance;

Therapeutic

relationship;

Clinical outcomes

1744-3881/$ - see front matter & 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.05.005

Tel.: +61 8 8302 2071; fax: +61 8 8302 2766.

E-mail address: matthew.leach@unisa.edu.au.

Rapport: A key to treatment success

Matthew J. Leach

School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia, North Terrace Adelaide SA 5000, South Australia

Summary The therapeutic relationship isa concept often ignored in current

literature. As such, the importance of good patient rapport may be overlooked. To

addressthese concerns,the following paperhighlightsthe effects that strong

therapeutic relationships may have on patient satisfaction, treatment compliance

and client outcomes.Strategiesthat practitionerscan employ to facilitate the

development of good patient rapport are also discussed.

& 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The first and most important objective of any

client–practitioner interaction is the establishment

of client rapport. Aside from facilitating commu-

nication between the practitioner and patient,

good patient rapport may also improve client

assessmentand the achievementof expected

treatmentoutcomes.1 Nonetheless,development

of the therapeutic relationship requires time and

skill.2 As the therapist’s contribution to this

alliance is often overlooked in the literature,3 the

purpose of this paper is to enlighten readers of the

importance of establishing a strong therapeutic

relationship with their clients, and to provide

practitionerswith useful strategiesto improve

client rapport in clinical practice. These skills

may also facilitate a practitioner’s ability to

develop effective working relationships with other

health care providers.4 Firstly however, an explora-

tion of the terms used to describe the therapeutic

relationship willallow readers to understand the

context in which this paper is situated.

Definitions

Many terms exist which describe the bond between

a client and practitioner. The terms most fre-

quently identified in the literature are therapeutic

alliance, therapeutic relationship and patient rap-

port. By definition, a therapeutic alliance is a

‘yconscious and active collaboration between the

patient and therapist’.3 Similarly,a therapeutic

relationship is ‘a trusting connection and rapport

established between therapist and client through

collaboration,communication,therapist empathy

and mutual understanding and respect’.4 Likewise,

patient rapport is defined as a ‘harmonious rela-

tionship’.5 As each of these terms incorporate

similar underlying themes, including collaboration,

reciprocality, parity and growth, these terms are

considered interchangeable.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/ctnm

KEYWORDS

Rapport;

Therapeutic

alliance;

Therapeutic

relationship;

Clinical outcomes

1744-3881/$ - see front matter & 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.05.005

Tel.: +61 8 8302 2071; fax: +61 8 8302 2766.

E-mail address: matthew.leach@unisa.edu.au.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Importance

There are many reasons why practitioners should

be encouragedto develop strong therapeutic

relationshipswith their clients. On the whole,

building and maintaining patient rapport leads to

positive client outcomes.6-8 A recent survey ex-

ploring the views of 129 Connecticut Occupational

Therapistson therapeutic relationshipssupports

this claim.4 Whilst descriptive surveys are not the

most appropriate design for evaluating causal

relationships,clinical evidence is beginningto

mount that validates the association between good

rapport and positive client outcomes.

To illustrate this, a cohort study involving 354

patients in a community-basednon-profit drug

treatment programme and 223 patientsfrom a

private for-profit programme, found lower levels of

client rapport during counsellingtreatment re-

sulted in poorer treatment outcomes,including

greater cocaine use and criminality.9 Likewise,

studiesof patients with non-chronic schizophre-

nia,10 depression,11 post-traumaticstress disor-

der12 and alcoholism13 demonstratethat good

patient rapport can improve treatment outcomes.

Although these studies suggest that the develop-

ment of a strong therapeuticrelationship may

benefit patients receiving psychotherapy,the ef-

fect of good client rapport on the outcomesof

interventions in other health care fields is lacking.

Further research is therefore needed to ascertain if

changes in practitioner behaviour can ameliorate

treatment success and reduce unnecessary demand

on existing health and welfare services.

A reason why well-established therapeutic rela-

tionshipsmay contribute to improved clientout-

comesmay be explained by increased treatment

compliance.14To support this claim, mothers attend-

ing a Los Angeles children’s hospital reported greater

treatment compliance when highly satisfied with a

physician’s attitude.15 Similarly,peri-operative pa-

tients reporting a higher levelof satisfaction with

their care were more likely to take responsibility for

their decisions.16Thus, client satisfaction appears to

be a strong motivator of treatment compliance and

as such, maybe fundamental to treatment success. In

other words, good client rapport may be responsible

for improving patientsatisfaction and treatment

compliance,7 and ameliorating patient outcomes.

Even though the needs of patients are a priority in

any consultation, there are also professional implica-

tions associated with building a therapeutic alliance.

Firstly, strong therapeuticrelationshipsbetween

patientsand cliniciansmay improve the public’s

perception ofa practitionergroup.4 Secondly,by

increasing client rapport and treatment compliance,

the risk of litigation may be reduced.6,15,17

Although

this claim is speculative, Eastaugh18 and Panting19

both agree that improving client trust and commu-

nication, such as that developedthrough good

rapport, results in fewer malpractice claims. Alter-

natively, because good patient rapport is critical to

formulating adequate diagnoses,15,20 practitioners

may misdiagnoseless frequently if therapeutic

alliances are well established.

Because the practitioneris predominantly re-

sponsible for developing and maintaining client

rapport,21 the following section will highlight

several useful strategies that clinicians can employ

to strengthen therapeutic relationsand improve

client outcomes.

Application

The clinician’s behaviour and communication style

can have significant impact on the practitioner–-

client relationship. For instance, therapists who are

warm, friendly (P ¼ 0:01),affirming and under-

standing (P ¼ 0:05),demonstrate a higherthera-

peutic alliance with their patients than those who

do not manifest these abovementioned qualities.22

These attributes may also increase client compli-

ance15and improve treatment outcomes.23Another

essentialingredientin the development of the

therapeutic relationship is time.

Developing patient rapport within the first few

minutes of a consultation builds client trust24 and

minimises defensive client attitudes by blurring the

transition from ‘small talk’ to formal assess-

ment.15,25 Increasing constraintson practitioner

time, such as escalating workloads, costs, organisa-

tional and political pressure, lessen the opportunity

for practitioners to build a strong rapport with their

clients.4,26

In support of the relationship between time and

rapport, a study examining623 tape-recorded

sessions between medicalpractitioners and their

patients found consultations that were booked for

10 minutes resulted in improved client education

and more detailed patient assessmentthan ap-

pointments booked for 7.5 minutes.27 Because time

constraintscan also have a negative impacton

client outcomes,4 adequate consultation time is

therefore as important as effective communication

skills. Thus, professions that can afford the luxury

of providing consultationsof unlimited duration

may establish greater therapeutic relationships

with their clients as opposed to practitioners

constrained by time. For clinicians where time is

scarce, strategies such as providing a quiet envir-

onment; actively listening; avoiding interruptions;

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Rapport: A key to treatment success 263

There are many reasons why practitioners should

be encouragedto develop strong therapeutic

relationshipswith their clients. On the whole,

building and maintaining patient rapport leads to

positive client outcomes.6-8 A recent survey ex-

ploring the views of 129 Connecticut Occupational

Therapistson therapeutic relationshipssupports

this claim.4 Whilst descriptive surveys are not the

most appropriate design for evaluating causal

relationships,clinical evidence is beginningto

mount that validates the association between good

rapport and positive client outcomes.

To illustrate this, a cohort study involving 354

patients in a community-basednon-profit drug

treatment programme and 223 patientsfrom a

private for-profit programme, found lower levels of

client rapport during counsellingtreatment re-

sulted in poorer treatment outcomes,including

greater cocaine use and criminality.9 Likewise,

studiesof patients with non-chronic schizophre-

nia,10 depression,11 post-traumaticstress disor-

der12 and alcoholism13 demonstratethat good

patient rapport can improve treatment outcomes.

Although these studies suggest that the develop-

ment of a strong therapeuticrelationship may

benefit patients receiving psychotherapy,the ef-

fect of good client rapport on the outcomesof

interventions in other health care fields is lacking.

Further research is therefore needed to ascertain if

changes in practitioner behaviour can ameliorate

treatment success and reduce unnecessary demand

on existing health and welfare services.

A reason why well-established therapeutic rela-

tionshipsmay contribute to improved clientout-

comesmay be explained by increased treatment

compliance.14To support this claim, mothers attend-

ing a Los Angeles children’s hospital reported greater

treatment compliance when highly satisfied with a

physician’s attitude.15 Similarly,peri-operative pa-

tients reporting a higher levelof satisfaction with

their care were more likely to take responsibility for

their decisions.16Thus, client satisfaction appears to

be a strong motivator of treatment compliance and

as such, maybe fundamental to treatment success. In

other words, good client rapport may be responsible

for improving patientsatisfaction and treatment

compliance,7 and ameliorating patient outcomes.

Even though the needs of patients are a priority in

any consultation, there are also professional implica-

tions associated with building a therapeutic alliance.

Firstly, strong therapeuticrelationshipsbetween

patientsand cliniciansmay improve the public’s

perception ofa practitionergroup.4 Secondly,by

increasing client rapport and treatment compliance,

the risk of litigation may be reduced.6,15,17

Although

this claim is speculative, Eastaugh18 and Panting19

both agree that improving client trust and commu-

nication, such as that developedthrough good

rapport, results in fewer malpractice claims. Alter-

natively, because good patient rapport is critical to

formulating adequate diagnoses,15,20 practitioners

may misdiagnoseless frequently if therapeutic

alliances are well established.

Because the practitioneris predominantly re-

sponsible for developing and maintaining client

rapport,21 the following section will highlight

several useful strategies that clinicians can employ

to strengthen therapeutic relationsand improve

client outcomes.

Application

The clinician’s behaviour and communication style

can have significant impact on the practitioner–-

client relationship. For instance, therapists who are

warm, friendly (P ¼ 0:01),affirming and under-

standing (P ¼ 0:05),demonstrate a higherthera-

peutic alliance with their patients than those who

do not manifest these abovementioned qualities.22

These attributes may also increase client compli-

ance15and improve treatment outcomes.23Another

essentialingredientin the development of the

therapeutic relationship is time.

Developing patient rapport within the first few

minutes of a consultation builds client trust24 and

minimises defensive client attitudes by blurring the

transition from ‘small talk’ to formal assess-

ment.15,25 Increasing constraintson practitioner

time, such as escalating workloads, costs, organisa-

tional and political pressure, lessen the opportunity

for practitioners to build a strong rapport with their

clients.4,26

In support of the relationship between time and

rapport, a study examining623 tape-recorded

sessions between medicalpractitioners and their

patients found consultations that were booked for

10 minutes resulted in improved client education

and more detailed patient assessmentthan ap-

pointments booked for 7.5 minutes.27 Because time

constraintscan also have a negative impacton

client outcomes,4 adequate consultation time is

therefore as important as effective communication

skills. Thus, professions that can afford the luxury

of providing consultationsof unlimited duration

may establish greater therapeutic relationships

with their clients as opposed to practitioners

constrained by time. For clinicians where time is

scarce, strategies such as providing a quiet envir-

onment; actively listening; avoiding interruptions;

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Rapport: A key to treatment success 263

and displaying non-hurried actions21 may portray to

the client that the practitioner has time to listen,

which may in turn facilitate greater disclosure of

client concerns. Whilst these strategies may assist

in developing rapportbetween practitionerand

adult clients, children may require additional

consideration.

In a study of 64 3.5-year-old children, the effects

of practitioner–child interaction on the establish-

ment of rapport were investigated.28 Children left

alone in a play room without their parent remained

with a stranger longer when the stranger greeted

the child quickly but interacted with the child for a

greater period of time. Children who were ap-

proached graduallyon the other had but only

interacted with the individual for a brief period of

time were also less likely to leave the playroom.

Thus, unlike adults, too much time spent trying to

establish rapport with a child may inversely effect

the establishment of a therapeutic alliance.28

A collaborative consultation style is also essential

to building a therapeutic relationship.3,5,14Such an

approach may empower the individualto partici-

pate in their care and allow the client to grow.5,29

Clinicians adopting a technicalor parentalrole as

opposed to a collaborative role may therefore

compromise patient rapport, respect, compliance

and treatment outcomes by invoking negative

client attitudes.26 Hence, a relationship where

the practitioner takes control and which the client

‘follows orders’ is neither conducive to patient

growth nor the development of good rapport. To

facilitate collaboration,practitionerscan take a

client centred approach; develop mutually agreed

goals with the patient;30 and involve the client’s

family in the consultation.4

Practitioners should also ensure that the client’s

right to make decisions about the choice of

treatment is retained and respected. Informed

consent is therefore criticalto establishing strong

therapeutic relationships. Equally important is the

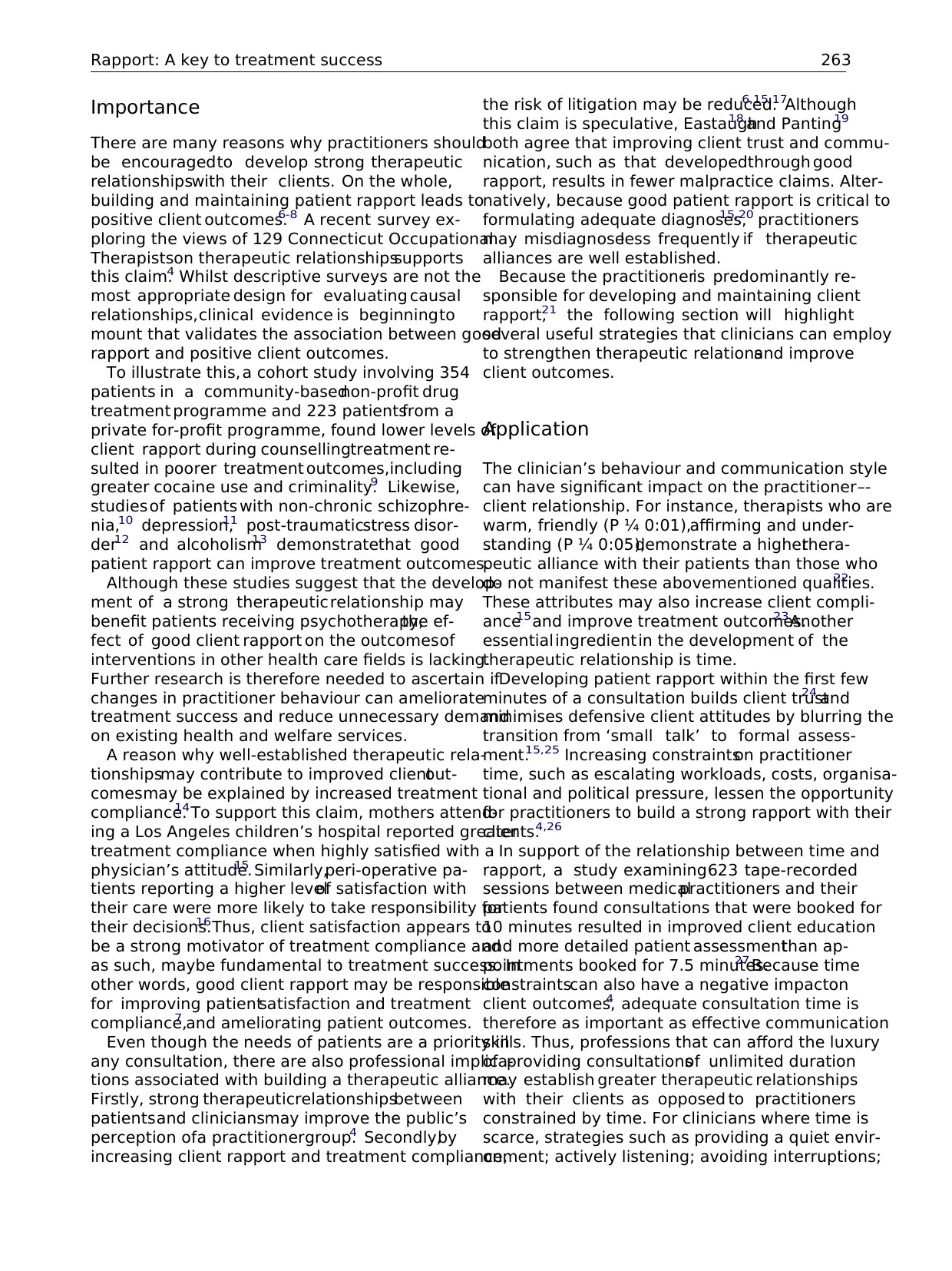

need for effective communication.

Practitioners choosing to develop strong thera-

peutic alliances with their clients will need to

possess skills that facilitate effective communica-

tion. Skills such as listening and responding are

fundamental to the exchange of information, as is

open questioning, reflecting, paraphrasingand

summarising.30 Effective communication and opti-

mal patient–practitionerinteraction also require

the clinician to identify and respect differences in

client gender, developmentalstages, cognitive

ability, values, beliefs, priorities, culture and social

circumstance.4,24Other strategies that foster com-

munication between clinician and client are listed

in Table 1.1–7,14,20,24,30,31,33,34

Of these strategies,

client trust is paramount. It is through trust and

respect that a practitioner can enhance commu-

nication and facilitate the developmentof the

therapeutic relationship.29,31However, client trust

is not a skill that can be acquired, but an attribute

that must be developed. Nonetheless, practitioners

who are clinically competent,consistent,honest

and committed to the client32 may accelerate the

development of patient trust, and in turn, improve

client communication, rapport and outcomes.

Awareness of the signs of increasing or worsening

rapport may allow practitioners to better evaluate the

strength ofa therapeutic relationship.Signsof a

growing therapeutic alliance may be manifested by an

increased flow of conversation;the disclosure of

sensitive information;relaxed bodylanguage;in-

creased eye contact; and improvements in listening

and responding.On the other hand, poor patient

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1 Practitionerstrategiesand behaviours

that improve client trust, communicationand

rapport.

Maintain: Client comfort

Confidentiality & trust

Enthusiasm

A collaborative relationship

Interest in client concerns

Objectivity

Attentiveness

Eye contact

An open posture

Avoid: Passing judgement

Jargon and technical language

An authoritarian demeanour

Interruptions

Be: Dependable

Open minded

Flexible

Reassuring & supportive

Confident

Friendly

Genuine

Warm

Sincere

Honest

Empowering

Engaging and interactive

Respectful of client wishes and

needs

Sensitive

Empathetic

Altruistic

Use: Open-ended questions

Rationales for procedures,

treatments and decisions

M.J. Leach264

the client that the practitioner has time to listen,

which may in turn facilitate greater disclosure of

client concerns. Whilst these strategies may assist

in developing rapportbetween practitionerand

adult clients, children may require additional

consideration.

In a study of 64 3.5-year-old children, the effects

of practitioner–child interaction on the establish-

ment of rapport were investigated.28 Children left

alone in a play room without their parent remained

with a stranger longer when the stranger greeted

the child quickly but interacted with the child for a

greater period of time. Children who were ap-

proached graduallyon the other had but only

interacted with the individual for a brief period of

time were also less likely to leave the playroom.

Thus, unlike adults, too much time spent trying to

establish rapport with a child may inversely effect

the establishment of a therapeutic alliance.28

A collaborative consultation style is also essential

to building a therapeutic relationship.3,5,14Such an

approach may empower the individualto partici-

pate in their care and allow the client to grow.5,29

Clinicians adopting a technicalor parentalrole as

opposed to a collaborative role may therefore

compromise patient rapport, respect, compliance

and treatment outcomes by invoking negative

client attitudes.26 Hence, a relationship where

the practitioner takes control and which the client

‘follows orders’ is neither conducive to patient

growth nor the development of good rapport. To

facilitate collaboration,practitionerscan take a

client centred approach; develop mutually agreed

goals with the patient;30 and involve the client’s

family in the consultation.4

Practitioners should also ensure that the client’s

right to make decisions about the choice of

treatment is retained and respected. Informed

consent is therefore criticalto establishing strong

therapeutic relationships. Equally important is the

need for effective communication.

Practitioners choosing to develop strong thera-

peutic alliances with their clients will need to

possess skills that facilitate effective communica-

tion. Skills such as listening and responding are

fundamental to the exchange of information, as is

open questioning, reflecting, paraphrasingand

summarising.30 Effective communication and opti-

mal patient–practitionerinteraction also require

the clinician to identify and respect differences in

client gender, developmentalstages, cognitive

ability, values, beliefs, priorities, culture and social

circumstance.4,24Other strategies that foster com-

munication between clinician and client are listed

in Table 1.1–7,14,20,24,30,31,33,34

Of these strategies,

client trust is paramount. It is through trust and

respect that a practitioner can enhance commu-

nication and facilitate the developmentof the

therapeutic relationship.29,31However, client trust

is not a skill that can be acquired, but an attribute

that must be developed. Nonetheless, practitioners

who are clinically competent,consistent,honest

and committed to the client32 may accelerate the

development of patient trust, and in turn, improve

client communication, rapport and outcomes.

Awareness of the signs of increasing or worsening

rapport may allow practitioners to better evaluate the

strength ofa therapeutic relationship.Signsof a

growing therapeutic alliance may be manifested by an

increased flow of conversation;the disclosure of

sensitive information;relaxed bodylanguage;in-

creased eye contact; and improvements in listening

and responding.On the other hand, poor patient

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1 Practitionerstrategiesand behaviours

that improve client trust, communicationand

rapport.

Maintain: Client comfort

Confidentiality & trust

Enthusiasm

A collaborative relationship

Interest in client concerns

Objectivity

Attentiveness

Eye contact

An open posture

Avoid: Passing judgement

Jargon and technical language

An authoritarian demeanour

Interruptions

Be: Dependable

Open minded

Flexible

Reassuring & supportive

Confident

Friendly

Genuine

Warm

Sincere

Honest

Empowering

Engaging and interactive

Respectful of client wishes and

needs

Sensitive

Empathetic

Altruistic

Use: Open-ended questions

Rationales for procedures,

treatments and decisions

M.J. Leach264

rapport may present as long periods of silence; sudden

withdrawalof conversation;33 lack of eye contact;

brief responses, and defensive body language.

In cases where a therapeutic relationship fails to

develop, the practitioner may need to critically

reflect on their techniques, the environment and

the client to isolate the factors that impede the

growth of patient rapport.The practitionermay

also choose to utilise the strategies listed in Table 1

to facilitate the development of strong therapeutic

relationships.

Conclusion

The development of a strong therapeutic alliance

and the subsequent production ofpositive client

outcomes are dependent on effective communica-

tion skills, practitionerbehaviour,collaboration,

time and trust. Adopting the techniques identified

in this paper may significantlyimprove patient

health and wellbeing, and the efficiency of health

care services. The therapeutic relationship there-

fore has widespread implications for the patient,

practitioner,community and health care system.

Even so, further research is needed to evaluate the

impact that rapport has on the outcomes of

medical, nursing, complementary and allied health

interventions.

References

1. DeLaune SC, Ladner PK. Fundamentals of nursing: standards

and practice. Albany: Delmar; 1998.

2. Kennedy M. In doc we trust:building rapport with young

patients takes time and skill. WMJ 2000;99(2):33–6.

3. Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ. A review of therapist char-

acteristicsand techniquespositively impacting the ther-

apeutic alliance. Clin Psychol Rev 2003;23(1):1–33.

4. Cole MB, McLean V.Therapeutic relationships re-defined.

Occup Ther Ment Health 2003;19(2):33–56.

5. Spink LM. Six steps to patient rapport. AD Nurse

1987;2(2):21–3.

6. Mejo SL. Communicationas it affects the therapeutic

alliance. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 1989;1(1):20–2.

7. O’ConnorGT, Gaylor MS, Nelson EC. Health counselling:

building patient rapport. Physician Assist 1985;9(3):154–5.

8. Paley G, Lawton D. Evidence-based practice: accounting for

the importance of the therapeutic relationship in the UK

National Health Service therapy provision.Counsel Psy-

chother Res 2001;1(1):12–7.

9. Joe GW, Simpson DD, DansereauDF, Rowan-SzalGA.

Relationships between counselling rapport and drug abuse

treatment outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52(9):1223–9.

10. Frank AF, Gunderson JG. The role of the therapeutic alliance

in the treatment of schizophrenia. Relationship to course

and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatr 1990;47(3):228–36.

11. Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM, Simmens S, Moyer J, Elkin I, Watkins

J, Pilkonis PA. The role of the therapeutic alliance in

psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy:findingsin the na-

tional institute of mentalhealth treatment of depression

collaborative research program.J Consult Clin Psychol

1996;64(3):532–9.

12. Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Chemtob CM. Therapeutic

alliance, negative mood regulation, and treatment outcome

in child abuse-relatedposttraumaticstress disorder. J

Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72(3):411–6.

13. ConnorsGJ, Carroll KM, DiClemente CC,Longabaugh R,

Donovan DM. The therapeutic alliance and its relationship to

alcoholism treatment participation and outcome. J Consult

Clin Psychol 1997;65(4):588–98.

14. Crellin K. Communication briefs. Nurs Manage

1999;30(1):49.

15. Jarratt L, Nord W. Establishing patient rapport and commu-

nication. S D J Med 1985;38(1):19–23.

16. Larsson US, SvardsuddK, Wedel H, Saljo R. Patient

involvement in decision-making in surgical and orthopaedic

practice: effects of outcome of operation and care process

on patients’ perception of their involvement in the decision-

making process. Scand J Caring Sci 1992;6(2):87–96.

17. DavisCM. Patient practitioner interaction, 3rd ed. New

Jersey: SLACK Inc.; 1998.

18. Eastaugh SR. Reducing litigation costs through better

patient communication. Physician Exec 2004;30(3):36–8.

19. Panting G. How to avoid being sued in clinicalpractice.

Postgrad Med J 2004;80(941):165–8.

20. Franke J. Communication tune-up:forty tips to improve

rapport with your patients. Tex Med 1996;92(3):36–42.

21. Purtilo R. Health professional and patient interaction

(fourth edition). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990.

22. Najavits LM, Strupp HH. Differences in the effectiveness of

psychodynamic therapists:a process-outcome study.Psy-

chotherapy 1994;31(1):114–23.

23. Williams DDR, Garner J. The case against ‘the evidence’: a

different perspective on evidence-based medicine.Br J

Psychiatr 2002;180:8–12.

24. Harkreader H. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical

judgement. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000.

25. Gumenick NR. Classical five-element acupuncture. Acupunc-

ture Today 2003;4(2).

26. Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, SchellBAB. Willard and Spackman’s

occupationaltherapy, 10th ed. Philadelphia:Lippincott,

Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

27. Roland MO, Bartholomew J, CourtenayMJ, Morris RW,

Morrell DC. The ‘‘five minute’’ consultation: effect of time

constraint on verbal communication. Br Med J

1986;292(6524):874–6.

28. Donate-Bartfield E, Passman RH. Establishing rapport with

preschool-age children: implications for practitioners. Child

Health Care 2000;29(3):179–88.

29. Fox V. Therapeutic alliance. Psychiatr Rehabil J

2002;26(2):203–4.

30. MacDonald P. Developing a therapeutic relationship. Prac-

tice Nurse 2003;26(6):56–9.

31. Myers DG. Psychology, 4th ed. New York: Worth Publishers;

1995.

32. Usherwood T.Understanding the consultation:evidence,

theory and practice.Buckingham:Open University Press;

1999.

33. Latey P. Placebo: a study of persuasionand rapport.

JBodywork Movement Ther 2000;4(2):123–36.

34. Ramjan LM. Nurses and the ‘therapeutic relationship’:

caring for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Adv Nurs

2004;45(5):495–503.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Rapport: A key to treatment success 265

withdrawalof conversation;33 lack of eye contact;

brief responses, and defensive body language.

In cases where a therapeutic relationship fails to

develop, the practitioner may need to critically

reflect on their techniques, the environment and

the client to isolate the factors that impede the

growth of patient rapport.The practitionermay

also choose to utilise the strategies listed in Table 1

to facilitate the development of strong therapeutic

relationships.

Conclusion

The development of a strong therapeutic alliance

and the subsequent production ofpositive client

outcomes are dependent on effective communica-

tion skills, practitionerbehaviour,collaboration,

time and trust. Adopting the techniques identified

in this paper may significantlyimprove patient

health and wellbeing, and the efficiency of health

care services. The therapeutic relationship there-

fore has widespread implications for the patient,

practitioner,community and health care system.

Even so, further research is needed to evaluate the

impact that rapport has on the outcomes of

medical, nursing, complementary and allied health

interventions.

References

1. DeLaune SC, Ladner PK. Fundamentals of nursing: standards

and practice. Albany: Delmar; 1998.

2. Kennedy M. In doc we trust:building rapport with young

patients takes time and skill. WMJ 2000;99(2):33–6.

3. Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ. A review of therapist char-

acteristicsand techniquespositively impacting the ther-

apeutic alliance. Clin Psychol Rev 2003;23(1):1–33.

4. Cole MB, McLean V.Therapeutic relationships re-defined.

Occup Ther Ment Health 2003;19(2):33–56.

5. Spink LM. Six steps to patient rapport. AD Nurse

1987;2(2):21–3.

6. Mejo SL. Communicationas it affects the therapeutic

alliance. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 1989;1(1):20–2.

7. O’ConnorGT, Gaylor MS, Nelson EC. Health counselling:

building patient rapport. Physician Assist 1985;9(3):154–5.

8. Paley G, Lawton D. Evidence-based practice: accounting for

the importance of the therapeutic relationship in the UK

National Health Service therapy provision.Counsel Psy-

chother Res 2001;1(1):12–7.

9. Joe GW, Simpson DD, DansereauDF, Rowan-SzalGA.

Relationships between counselling rapport and drug abuse

treatment outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52(9):1223–9.

10. Frank AF, Gunderson JG. The role of the therapeutic alliance

in the treatment of schizophrenia. Relationship to course

and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatr 1990;47(3):228–36.

11. Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM, Simmens S, Moyer J, Elkin I, Watkins

J, Pilkonis PA. The role of the therapeutic alliance in

psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy:findingsin the na-

tional institute of mentalhealth treatment of depression

collaborative research program.J Consult Clin Psychol

1996;64(3):532–9.

12. Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Chemtob CM. Therapeutic

alliance, negative mood regulation, and treatment outcome

in child abuse-relatedposttraumaticstress disorder. J

Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72(3):411–6.

13. ConnorsGJ, Carroll KM, DiClemente CC,Longabaugh R,

Donovan DM. The therapeutic alliance and its relationship to

alcoholism treatment participation and outcome. J Consult

Clin Psychol 1997;65(4):588–98.

14. Crellin K. Communication briefs. Nurs Manage

1999;30(1):49.

15. Jarratt L, Nord W. Establishing patient rapport and commu-

nication. S D J Med 1985;38(1):19–23.

16. Larsson US, SvardsuddK, Wedel H, Saljo R. Patient

involvement in decision-making in surgical and orthopaedic

practice: effects of outcome of operation and care process

on patients’ perception of their involvement in the decision-

making process. Scand J Caring Sci 1992;6(2):87–96.

17. DavisCM. Patient practitioner interaction, 3rd ed. New

Jersey: SLACK Inc.; 1998.

18. Eastaugh SR. Reducing litigation costs through better

patient communication. Physician Exec 2004;30(3):36–8.

19. Panting G. How to avoid being sued in clinicalpractice.

Postgrad Med J 2004;80(941):165–8.

20. Franke J. Communication tune-up:forty tips to improve

rapport with your patients. Tex Med 1996;92(3):36–42.

21. Purtilo R. Health professional and patient interaction

(fourth edition). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990.

22. Najavits LM, Strupp HH. Differences in the effectiveness of

psychodynamic therapists:a process-outcome study.Psy-

chotherapy 1994;31(1):114–23.

23. Williams DDR, Garner J. The case against ‘the evidence’: a

different perspective on evidence-based medicine.Br J

Psychiatr 2002;180:8–12.

24. Harkreader H. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical

judgement. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000.

25. Gumenick NR. Classical five-element acupuncture. Acupunc-

ture Today 2003;4(2).

26. Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, SchellBAB. Willard and Spackman’s

occupationaltherapy, 10th ed. Philadelphia:Lippincott,

Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

27. Roland MO, Bartholomew J, CourtenayMJ, Morris RW,

Morrell DC. The ‘‘five minute’’ consultation: effect of time

constraint on verbal communication. Br Med J

1986;292(6524):874–6.

28. Donate-Bartfield E, Passman RH. Establishing rapport with

preschool-age children: implications for practitioners. Child

Health Care 2000;29(3):179–88.

29. Fox V. Therapeutic alliance. Psychiatr Rehabil J

2002;26(2):203–4.

30. MacDonald P. Developing a therapeutic relationship. Prac-

tice Nurse 2003;26(6):56–9.

31. Myers DG. Psychology, 4th ed. New York: Worth Publishers;

1995.

32. Usherwood T.Understanding the consultation:evidence,

theory and practice.Buckingham:Open University Press;

1999.

33. Latey P. Placebo: a study of persuasionand rapport.

JBodywork Movement Ther 2000;4(2):123–36.

34. Ramjan LM. Nurses and the ‘therapeutic relationship’:

caring for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Adv Nurs

2004;45(5):495–503.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Rapport: A key to treatment success 265

1 out of 4

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.