Lifespan Nutrition Research Paper 2022

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/14

|14

|3770

|12

AI Summary

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: LIFESPAN NUTRITION

LIFESPAN NUTRITION

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

LIFESPAN NUTRITION

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1LIFESPAN NUTRITION

Part A

Physiological Changes and Nutrition Requirements

One of the major physiological changes associated with ageing is sarcopenia – which

implies an age associated loss of the numbers and size of muscle fibers. Muscle changes are also

accompanied by the loss of bone density due to hindrances in bone remodeling mechanisms [1].

Not only do these age-associated physiological changes result in lean muscle mass loss and

frailty, but also results in increased protein and calcium based nutritional needs across the elderly

[2].

Ageing is also associated increased rates of oxidative stress and resultant inflammatory

neuronal atrophy, cerebral shrinkage and emergence of neurodegenerative diseases. The

increased oxidative stress also results in immunological compromises and accumulation of

advanced glycation end products (AGEs) which increase the risk of chronic and infectious

disease acquisition across the elderly. Such immunological impacts across the elderly enhance

the nutritional needs of consuming a diet rich in antioxidants and micronutrients [3].

Nutritional Concerns

With ageing, the stomach’s ability to secret digestive juices decreases resulting in

digestive difficulties as well as hindrances in the absorption and cellular assimilation of nutrients

within the body. This results in decreased appetite, increased incidences of gastrointestinal

disturbances and reduced ability to utilize nutrients from the food consumed [4]. This implies

that the digestive and absorptive capacities of the elderly within the aged care facility must be

Part A

Physiological Changes and Nutrition Requirements

One of the major physiological changes associated with ageing is sarcopenia – which

implies an age associated loss of the numbers and size of muscle fibers. Muscle changes are also

accompanied by the loss of bone density due to hindrances in bone remodeling mechanisms [1].

Not only do these age-associated physiological changes result in lean muscle mass loss and

frailty, but also results in increased protein and calcium based nutritional needs across the elderly

[2].

Ageing is also associated increased rates of oxidative stress and resultant inflammatory

neuronal atrophy, cerebral shrinkage and emergence of neurodegenerative diseases. The

increased oxidative stress also results in immunological compromises and accumulation of

advanced glycation end products (AGEs) which increase the risk of chronic and infectious

disease acquisition across the elderly. Such immunological impacts across the elderly enhance

the nutritional needs of consuming a diet rich in antioxidants and micronutrients [3].

Nutritional Concerns

With ageing, the stomach’s ability to secret digestive juices decreases resulting in

digestive difficulties as well as hindrances in the absorption and cellular assimilation of nutrients

within the body. This results in decreased appetite, increased incidences of gastrointestinal

disturbances and reduced ability to utilize nutrients from the food consumed [4]. This implies

that the digestive and absorptive capacities of the elderly within the aged care facility must be

2LIFESPAN NUTRITION

considered and hence, calls for the need to provide them nutritious foods which are easily to

digest and hence can easily be utilized for positive health sustenance [5].

Neuronal loss during ageing is associated with decreased sensory abilities within the

elderly resulting in reduced taste and olfactory acuity. This results in the elderly finding it

difficult to acquire the same smell and taste of food as compared to adulthood as well as

encountering difficulties in the swallowing and ingestion of food. Such changes coupled with

loss of appetite and digestive capacity reduce food intake across the elderly [6]. Reduced food

intake along with age associated catabolism result in nutritional concerns in the form of

malnutrition, poor or deficient nutrient status and aggravated frailty and disease risk across the

elderly. Thus, to assist in food consumption and nutritional absorption, there is a need to provide

texturally modified and nutritionally balanced foods [7].

ABCD Indicators

Considering that osteoporosis is characterized by losses in bone mass and density – it is

likely that individuals with a small skeletal frame and reduced bone mass are at risk of acquiring

the condition. This implies that prevalence of frailty and abnormally low body mass are

anthropometric risk factors indicative of osteoporosis susceptibility across the elderly [8].

Nutrients like calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D are essential for bone development. Thus

abnormally low serum levels of calcium, phosphorous and vitamin D are key clinical indicators

that can be used to assess osteoporosis risk within the elderly of the aged care facility [9]. Due to

its association with loss of bone density, a bone density value of 2.5 standard deviations or lower

as compared to mean values in adults is indicative of osteoporosis risk within the elderly.

Additionally, a diet which is inadequate in calcium and vitamin D-rich foods like dairy, fortified

considered and hence, calls for the need to provide them nutritious foods which are easily to

digest and hence can easily be utilized for positive health sustenance [5].

Neuronal loss during ageing is associated with decreased sensory abilities within the

elderly resulting in reduced taste and olfactory acuity. This results in the elderly finding it

difficult to acquire the same smell and taste of food as compared to adulthood as well as

encountering difficulties in the swallowing and ingestion of food. Such changes coupled with

loss of appetite and digestive capacity reduce food intake across the elderly [6]. Reduced food

intake along with age associated catabolism result in nutritional concerns in the form of

malnutrition, poor or deficient nutrient status and aggravated frailty and disease risk across the

elderly. Thus, to assist in food consumption and nutritional absorption, there is a need to provide

texturally modified and nutritionally balanced foods [7].

ABCD Indicators

Considering that osteoporosis is characterized by losses in bone mass and density – it is

likely that individuals with a small skeletal frame and reduced bone mass are at risk of acquiring

the condition. This implies that prevalence of frailty and abnormally low body mass are

anthropometric risk factors indicative of osteoporosis susceptibility across the elderly [8].

Nutrients like calcium, phosphorus and vitamin D are essential for bone development. Thus

abnormally low serum levels of calcium, phosphorous and vitamin D are key clinical indicators

that can be used to assess osteoporosis risk within the elderly of the aged care facility [9]. Due to

its association with loss of bone density, a bone density value of 2.5 standard deviations or lower

as compared to mean values in adults is indicative of osteoporosis risk within the elderly.

Additionally, a diet which is inadequate in calcium and vitamin D-rich foods like dairy, fortified

3LIFESPAN NUTRITION

cereals, butter, mushrooms, soy, fatty fish, nuts and seeds is a major dietary indicator

highlighting the risk of osteoporosis [10].

Part B

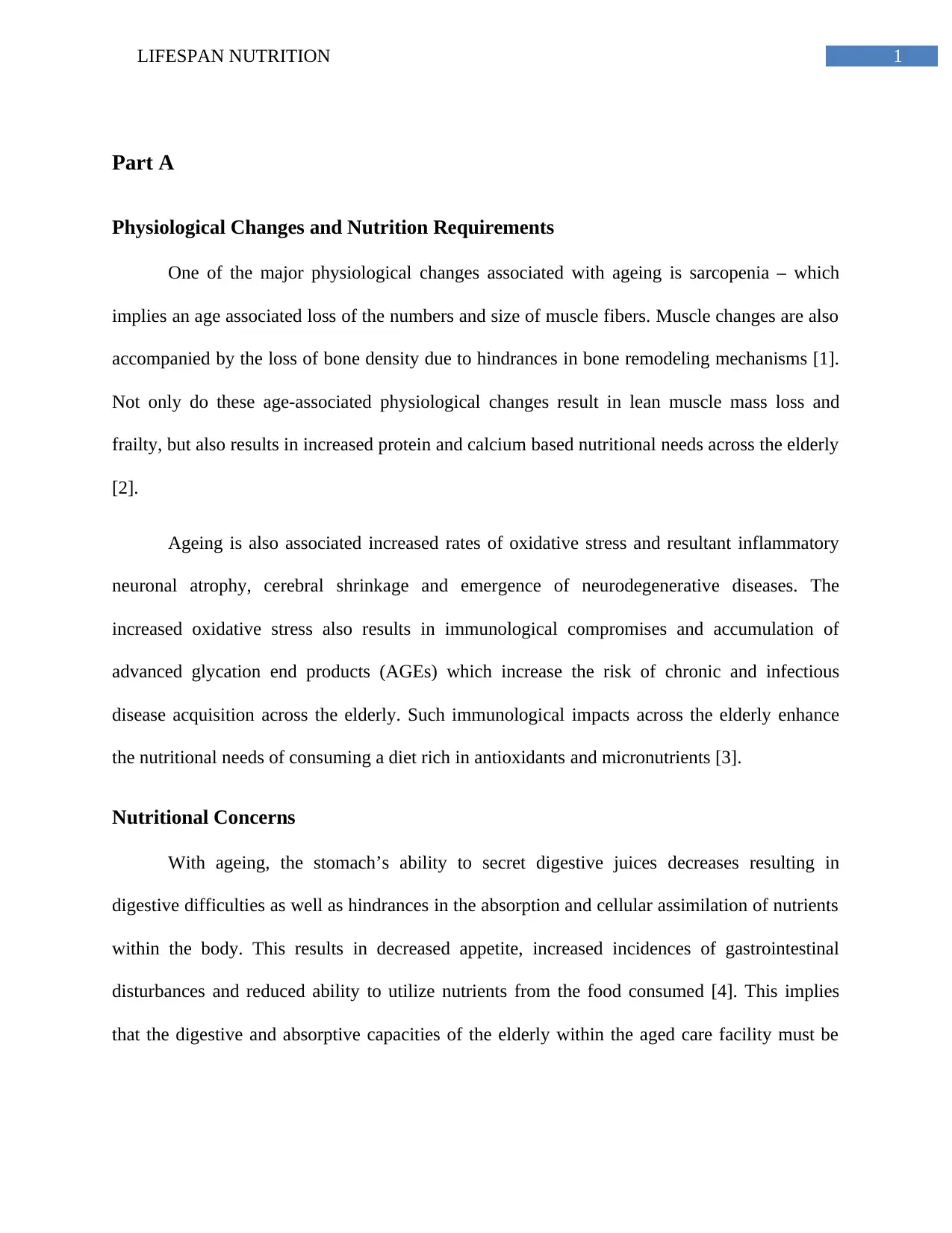

Table 1. Food Intake Analysis

Nutrient (per day) Amount Nutrient Reference Values

[11]

Energy, kJ 4307 kJ EERM: 6517 kJ, DEER: 7121

kJ

Carbohydrates: Grams, % E 115 g, 44% AMDR: 45 to 65%

Proteins: Grams, % E 51 g, 20% RDI: 47 g, AMDR: 15 to 25%

Total Fat: Grams, % E 39 g, 33% AMDR: 20 to 35%

Saturated Fat: Grams, % E 15 g, 13% AMDR: Less than 10%

Water, g 1763 g AI: 2800 g

Fiber, g 10 g AI: 25 g

Sodium, mg 1126.58 mg AI: 460 mg

Iron, mg 6.98 mg EAR: 5 mg, RDI: 8 mg, UL:

45 mg

Zinc, mg 4.60 mg EAR: 6.5 mg, RDI: 8 mg, UL:

40 mg

Iodine, μg 71.35 μmg EAR: 100 μg, RDI: 150 μg,

UL: 1100 μg

Calcium, mg 445.59 mg EAR: 1100 mg, RDI: 1300

mg, UI: 2500 mg

Vitamin C, mg 46.91 mg EAR: 30 mg, RDI: 45

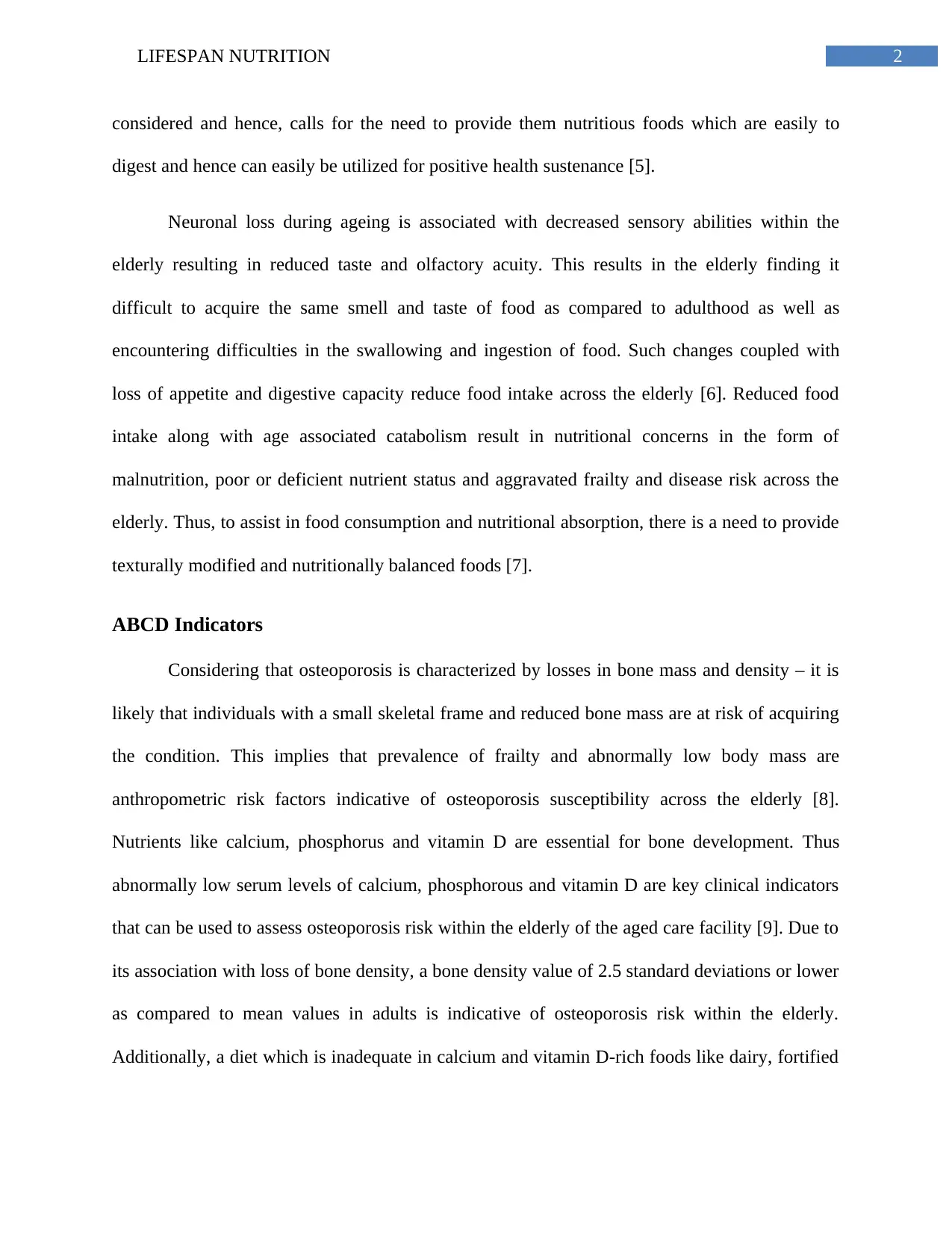

Table 2. Servings Consumed

Food Groups Number of serves consumed ADG recommended servings

[12]

Grain (cereal) foods 0.4 3

Vegetables and legume/beans Vegetables: 1.7, Legumes: 0.0 5

Fruit Fruit: 0.0 2

Lean meats and poultry, fish,

eggs, tofu, nuts, seeds and

legumes/beans

Lean meats and poultry: 0, fish:

0, eggs: 0, soy products: 0.0, nuts

and seeds: 0.0, legumes/beans:

0.0

2

Milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or

alternatives, mostly reduced fat

0.4 4

cereals, butter, mushrooms, soy, fatty fish, nuts and seeds is a major dietary indicator

highlighting the risk of osteoporosis [10].

Part B

Table 1. Food Intake Analysis

Nutrient (per day) Amount Nutrient Reference Values

[11]

Energy, kJ 4307 kJ EERM: 6517 kJ, DEER: 7121

kJ

Carbohydrates: Grams, % E 115 g, 44% AMDR: 45 to 65%

Proteins: Grams, % E 51 g, 20% RDI: 47 g, AMDR: 15 to 25%

Total Fat: Grams, % E 39 g, 33% AMDR: 20 to 35%

Saturated Fat: Grams, % E 15 g, 13% AMDR: Less than 10%

Water, g 1763 g AI: 2800 g

Fiber, g 10 g AI: 25 g

Sodium, mg 1126.58 mg AI: 460 mg

Iron, mg 6.98 mg EAR: 5 mg, RDI: 8 mg, UL:

45 mg

Zinc, mg 4.60 mg EAR: 6.5 mg, RDI: 8 mg, UL:

40 mg

Iodine, μg 71.35 μmg EAR: 100 μg, RDI: 150 μg,

UL: 1100 μg

Calcium, mg 445.59 mg EAR: 1100 mg, RDI: 1300

mg, UI: 2500 mg

Vitamin C, mg 46.91 mg EAR: 30 mg, RDI: 45

Table 2. Servings Consumed

Food Groups Number of serves consumed ADG recommended servings

[12]

Grain (cereal) foods 0.4 3

Vegetables and legume/beans Vegetables: 1.7, Legumes: 0.0 5

Fruit Fruit: 0.0 2

Lean meats and poultry, fish,

eggs, tofu, nuts, seeds and

legumes/beans

Lean meats and poultry: 0, fish:

0, eggs: 0, soy products: 0.0, nuts

and seeds: 0.0, legumes/beans:

0.0

2

Milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or

alternatives, mostly reduced fat

0.4 4

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4LIFESPAN NUTRITION

3. Dietary Intake

One of the first components of dietary intake which is of significance is the Agnes’s

inadequate consumption of energy. It can be observed that Agnes’s total energy intake is much

less as compared to the recommended Nutrient Reference Values (NRV) (Table 1). The reasons

underlying such low calorie intake can be attributed to the types of food servings prevalent in her

diet. It is known that carbohydrates, especially whole grains, fresh fruits, legumes, beans and

even foods which contain moderate quantities of fats, such as nuts and seeds, are key

contributors to an individual’s energy intake [13]. Not only is Agnes’s present diet inadequate in

total calories, she is also consuming deficient servings of the above energy-giving foods. Old age

accompanied by catabolism and increased muscle wastage. Thus, consumption of a diet low in

energy is likely to result in muscle mass loss, frailty and anthropometric measurements within

the elderly individual [14]. Indeed, such an association between inadequate dietary intake and

abnormally low anthropometric measurements like BMI can be observed in Agnes. Such

inadequate dietary consumption may aggravate rates of catabolism and result in loss of tissue and

immunological capacity in elderly individuals like Agnes – thus increasing her risk for chronic

disease acquisition in the process [15].

Findings from her dietary intake analysis indeed indicate her consumption of sodium to

much higher than the recommended NRVs (Table 1). A high consumption of sodium is

associated with hypertension – as evident in Agnes’s present conditions [16]. Further, ageing is

associated with cardiovascular changes such as: atrial fibrillation, stiffening of the blood vessels

and valves and reduced functioning of cardiac baroreceptors – the primary physiological agents

which play a key role in regulating the body’s blood pressure. Thus, age related mechanisms will

3. Dietary Intake

One of the first components of dietary intake which is of significance is the Agnes’s

inadequate consumption of energy. It can be observed that Agnes’s total energy intake is much

less as compared to the recommended Nutrient Reference Values (NRV) (Table 1). The reasons

underlying such low calorie intake can be attributed to the types of food servings prevalent in her

diet. It is known that carbohydrates, especially whole grains, fresh fruits, legumes, beans and

even foods which contain moderate quantities of fats, such as nuts and seeds, are key

contributors to an individual’s energy intake [13]. Not only is Agnes’s present diet inadequate in

total calories, she is also consuming deficient servings of the above energy-giving foods. Old age

accompanied by catabolism and increased muscle wastage. Thus, consumption of a diet low in

energy is likely to result in muscle mass loss, frailty and anthropometric measurements within

the elderly individual [14]. Indeed, such an association between inadequate dietary intake and

abnormally low anthropometric measurements like BMI can be observed in Agnes. Such

inadequate dietary consumption may aggravate rates of catabolism and result in loss of tissue and

immunological capacity in elderly individuals like Agnes – thus increasing her risk for chronic

disease acquisition in the process [15].

Findings from her dietary intake analysis indeed indicate her consumption of sodium to

much higher than the recommended NRVs (Table 1). A high consumption of sodium is

associated with hypertension – as evident in Agnes’s present conditions [16]. Further, ageing is

associated with cardiovascular changes such as: atrial fibrillation, stiffening of the blood vessels

and valves and reduced functioning of cardiac baroreceptors – the primary physiological agents

which play a key role in regulating the body’s blood pressure. Thus, age related mechanisms will

5LIFESPAN NUTRITION

aggravate the hypertensive effects of a high sodium diet and hence, increase the risk of an elderly

person like Agnes to acquire fatal cardiovascular consequences such as myocardial infarction

and stroke [17].

Additionally, it is known to us that Agnes has high levels of blood cholesterol. From the

dietary intake analysis results, it can be observed that while Agnes’s consumption of total fats is

within recommended NRV values, her saturated fat intake is exceeding the recommendations

(Table 1). Interestingly, it can be observed that Agnes is not consuming any food servings which

are potential sources of saturated fat – that is, red meats or processed foods. However, the

serving intake findings reveal that Agnes is consuming other sources of saturated fats, that is,

ham, butter and mayonnaise [18]. Further, Agnes’s diet is deficient in any form of unsaturated

fats such as oils, nuts and seeds. (Table 2). The type also reveals Agnes’s prevalent consumption

of foods rich in added sugars such as marmalade, packaged biscuits and processed fruit juices

(Table 2). As highlighted previously, ageing is associated with lower metabolic rates and

muscular mass which is why, the elderly find it difficult to metabolize nutrients in their food,

which is why it is likely that the calories obtained from Agnes’s sugar consumption are being

rapidly metabolized into adipose tissue accumulations [19]. Thus, even though Agnes’s

consumption of food servings are relatively low, her increased sugar and saturated fat

consumption coupled with the physiological and metabolic impacts of ageing have contributed to

her high cholesterol levels. If not controlled, excessive consumption of foods rich in saturated fat

and sugars have been evidenced to increase blood levels of cholesterol and triglycerides – as

observed in Agnes – which can further increase her risk of acquiring cardiovascular diseases like

stroke and myocardial infarction [20]. It has also been evidenced that cardiovascular disease risk

due to the high blood cholesterol are further enhanced due to hypertension – another condition

aggravate the hypertensive effects of a high sodium diet and hence, increase the risk of an elderly

person like Agnes to acquire fatal cardiovascular consequences such as myocardial infarction

and stroke [17].

Additionally, it is known to us that Agnes has high levels of blood cholesterol. From the

dietary intake analysis results, it can be observed that while Agnes’s consumption of total fats is

within recommended NRV values, her saturated fat intake is exceeding the recommendations

(Table 1). Interestingly, it can be observed that Agnes is not consuming any food servings which

are potential sources of saturated fat – that is, red meats or processed foods. However, the

serving intake findings reveal that Agnes is consuming other sources of saturated fats, that is,

ham, butter and mayonnaise [18]. Further, Agnes’s diet is deficient in any form of unsaturated

fats such as oils, nuts and seeds. (Table 2). The type also reveals Agnes’s prevalent consumption

of foods rich in added sugars such as marmalade, packaged biscuits and processed fruit juices

(Table 2). As highlighted previously, ageing is associated with lower metabolic rates and

muscular mass which is why, the elderly find it difficult to metabolize nutrients in their food,

which is why it is likely that the calories obtained from Agnes’s sugar consumption are being

rapidly metabolized into adipose tissue accumulations [19]. Thus, even though Agnes’s

consumption of food servings are relatively low, her increased sugar and saturated fat

consumption coupled with the physiological and metabolic impacts of ageing have contributed to

her high cholesterol levels. If not controlled, excessive consumption of foods rich in saturated fat

and sugars have been evidenced to increase blood levels of cholesterol and triglycerides – as

observed in Agnes – which can further increase her risk of acquiring cardiovascular diseases like

stroke and myocardial infarction [20]. It has also been evidenced that cardiovascular disease risk

due to the high blood cholesterol are further enhanced due to hypertension – another condition

6LIFESPAN NUTRITION

which has been observed in Agnes. Thus, the above analysis clearly reveals the link between

Agnes’s present food consumption patterns and her existing medical conditions [21 ] .

Upon closely evaluating the dietary intake analysis of Agnes’s food consumption, it can

be observed that the her intake of calcium is deficient in comparison to the recommended NRVs

(Table 1). Not only is Agnes’s diet devoid of any form of foods rich in calcium (dairy, nuts,

seeds, green leafy vegetables) (Table 2) her BMI also belongs to the below normal range. Such

findings are of concern since frailty, underweight status and a diet deficient in calcium are major

risk factors of osteoporosis within the elderly [22]. Agnes has also been found to spend most of

time indoors - thus depriving her of vitamin D from sunlight, the key nutrient responsible for the

enhancing calcium absorption. Thus, taking insights from the results of her dietary and

anthropometric measurements, therapeutic interventions must be immediately taken to correct

Agnes’s risk and her potential susceptibility of acquiring fractures in the future [23].

4. Reasons for Inadequacy

It is known that old age is associated with decreased sensory capacity and neuronal loss

result in loss of appetite and a loss of the ability to understand the olfactory qualities of food

[24]. Thus, to assess the reasons underlying Agnes’s inadequate dietary intake, an assessment

targeting her loss of appetite, that is, ‘orthorexia’ can be conducted. A useful assessment tool for

evaluating the reasons underlying Agnes’s inadequate intake would be the Bratman Test for

Orthorexia which used 10 questions to associated self-esteem and quality of life to a client’s

dietary intake [25].

It is also further known that old age is associated with dental and bone loss resulting in

difficulties to chew and swallow food. Thus, a 9 point sensory evaluation can be conducted to

which has been observed in Agnes. Thus, the above analysis clearly reveals the link between

Agnes’s present food consumption patterns and her existing medical conditions [21 ] .

Upon closely evaluating the dietary intake analysis of Agnes’s food consumption, it can

be observed that the her intake of calcium is deficient in comparison to the recommended NRVs

(Table 1). Not only is Agnes’s diet devoid of any form of foods rich in calcium (dairy, nuts,

seeds, green leafy vegetables) (Table 2) her BMI also belongs to the below normal range. Such

findings are of concern since frailty, underweight status and a diet deficient in calcium are major

risk factors of osteoporosis within the elderly [22]. Agnes has also been found to spend most of

time indoors - thus depriving her of vitamin D from sunlight, the key nutrient responsible for the

enhancing calcium absorption. Thus, taking insights from the results of her dietary and

anthropometric measurements, therapeutic interventions must be immediately taken to correct

Agnes’s risk and her potential susceptibility of acquiring fractures in the future [23].

4. Reasons for Inadequacy

It is known that old age is associated with decreased sensory capacity and neuronal loss

result in loss of appetite and a loss of the ability to understand the olfactory qualities of food

[24]. Thus, to assess the reasons underlying Agnes’s inadequate dietary intake, an assessment

targeting her loss of appetite, that is, ‘orthorexia’ can be conducted. A useful assessment tool for

evaluating the reasons underlying Agnes’s inadequate intake would be the Bratman Test for

Orthorexia which used 10 questions to associated self-esteem and quality of life to a client’s

dietary intake [25].

It is also further known that old age is associated with dental and bone loss resulting in

difficulties to chew and swallow food. Thus, a 9 point sensory evaluation can be conducted to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7LIFESPAN NUTRITION

understand what sensory parameters in food provided contributes to Agnes’s poor appetite.

Based on the same, the aged care home may be advised to provided texturally modified foods

catered to Agnes’s needs [26]. Lastly, a lack of appetite is often associated with underlying

chronic conditions in an individual, such as hepatic, heart and renal diseases as well as cancer

and chronic pulmonary disorders. Thus, additionally respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and

hepatic enzyme assessments can be conducted to detect Agnes’ reasons for low dietary intake

[27].

5. Potential Strategies

The following strategies can be recommended to the aged care facility to improve

Agnes’s inadequate diet intake.

1. It is recommended that hard foods like toast and crackers are replaced with softer foods

such as lightly toasted or untoasted breads prepared with a mix of whole as well as

refined flours. Not only will this enhanced the intake of dietary intake across the elderly

but will also make it easier for them to chew and swallow foods [28].

2. It is recommended that the aged care facility replace all saturated fat sources with

unsaturated sources like low fat dairy, low fat cottage cheese, yoghurt and olive oil. This

will reduced the risk if hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular disease risk in the

elderly like Agnes as well enhanced digestion and calcium and healthy unsaturated fat

consumption [29].

3. Agnes’s diet reveals the abundance of sugary foods given as snacks to the elderly. It is

advisable to replace sugary biscuits and crackers with stewed fruits (without sugars),

steamed salads with added nuts or fruit and seed smoothies. This will be easier for the

understand what sensory parameters in food provided contributes to Agnes’s poor appetite.

Based on the same, the aged care home may be advised to provided texturally modified foods

catered to Agnes’s needs [26]. Lastly, a lack of appetite is often associated with underlying

chronic conditions in an individual, such as hepatic, heart and renal diseases as well as cancer

and chronic pulmonary disorders. Thus, additionally respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and

hepatic enzyme assessments can be conducted to detect Agnes’ reasons for low dietary intake

[27].

5. Potential Strategies

The following strategies can be recommended to the aged care facility to improve

Agnes’s inadequate diet intake.

1. It is recommended that hard foods like toast and crackers are replaced with softer foods

such as lightly toasted or untoasted breads prepared with a mix of whole as well as

refined flours. Not only will this enhanced the intake of dietary intake across the elderly

but will also make it easier for them to chew and swallow foods [28].

2. It is recommended that the aged care facility replace all saturated fat sources with

unsaturated sources like low fat dairy, low fat cottage cheese, yoghurt and olive oil. This

will reduced the risk if hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular disease risk in the

elderly like Agnes as well enhanced digestion and calcium and healthy unsaturated fat

consumption [29].

3. Agnes’s diet reveals the abundance of sugary foods given as snacks to the elderly. It is

advisable to replace sugary biscuits and crackers with stewed fruits (without sugars),

steamed salads with added nuts or fruit and seed smoothies. This will be easier for the

8LIFESPAN NUTRITION

elderly to ingest and also contribute to reduced sugar intake and improved fiber, calcium,

antioxidants, unsaturated fat and micronutrient intake [30].

4. Lastly, to improve protein, fiber, calcium and antioxidant consumption, it is advisable

that the aged care facility replace red meats with lean and vegetarian protein sources like

soy, legumes, nuts, seeds and steamed or boiled fatty fish, skinless chicken and eggs [31]

elderly to ingest and also contribute to reduced sugar intake and improved fiber, calcium,

antioxidants, unsaturated fat and micronutrient intake [30].

4. Lastly, to improve protein, fiber, calcium and antioxidant consumption, it is advisable

that the aged care facility replace red meats with lean and vegetarian protein sources like

soy, legumes, nuts, seeds and steamed or boiled fatty fish, skinless chicken and eggs [31]

9LIFESPAN NUTRITION

References

1. Rondanelli M, Faliva M, Monteferrario F, Peroni G, Repaci E, Allieri F, Perna S. Novel

insights on nutrient management of sarcopenia in elderly. InClinical Nutrition and Aging

2017 Oct 2 (pp. 35-66). Apple Academic Press.

2. Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Nishikawa K, Nagatsuma Y, Nakayama T, Tanikawa

S, Maeda S, Uemura M, Miyake M, Hama N. Sarcopenia is associated with severe

postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy.

Gastric Cancer. 2016 Jul 1;19(3):986-93.

3. Gautieri A, Passini FS, Silván U, Guizar-Sicairos M, Carimati G, Volpi P, Moretti M,

Schoenhuber H, Redaelli A, Berli M, Snedeker JG. Advanced glycation end-products:

mechanics of aged collagen from molecule to tissue. Matrix Biology. 2017 May 1;59:95-

108.

4. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Kiesswetter E, Drey M, Sieber CC. Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia.

Aging clinical and experimental research. 2017 Feb 1;29(1):43-8.

5. Hopkinson JB. Nutritional support of the elderly cancer patient: The role of the nurse.

Nutrition. 2015 Apr 1;31(4):598-602.

6. Peyron MA, Woda A, Bourdiol P, Hennequin M. Age‐related changes in mastication.

Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2017 Apr;44(4):299-312.

7. Bernstein M, Munoz N. Nutrition for the older adult. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2019 Jan

2.

References

1. Rondanelli M, Faliva M, Monteferrario F, Peroni G, Repaci E, Allieri F, Perna S. Novel

insights on nutrient management of sarcopenia in elderly. InClinical Nutrition and Aging

2017 Oct 2 (pp. 35-66). Apple Academic Press.

2. Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Nishikawa K, Nagatsuma Y, Nakayama T, Tanikawa

S, Maeda S, Uemura M, Miyake M, Hama N. Sarcopenia is associated with severe

postoperative complications in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy.

Gastric Cancer. 2016 Jul 1;19(3):986-93.

3. Gautieri A, Passini FS, Silván U, Guizar-Sicairos M, Carimati G, Volpi P, Moretti M,

Schoenhuber H, Redaelli A, Berli M, Snedeker JG. Advanced glycation end-products:

mechanics of aged collagen from molecule to tissue. Matrix Biology. 2017 May 1;59:95-

108.

4. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Kiesswetter E, Drey M, Sieber CC. Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia.

Aging clinical and experimental research. 2017 Feb 1;29(1):43-8.

5. Hopkinson JB. Nutritional support of the elderly cancer patient: The role of the nurse.

Nutrition. 2015 Apr 1;31(4):598-602.

6. Peyron MA, Woda A, Bourdiol P, Hennequin M. Age‐related changes in mastication.

Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2017 Apr;44(4):299-312.

7. Bernstein M, Munoz N. Nutrition for the older adult. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2019 Jan

2.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

10LIFESPAN NUTRITION

8. Li G, Thabane L, Papaioannou A, Ioannidis G, Levine MA, Adachi JD. An overview of

osteoporosis and frailty in the elderly. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017

Dec;18(1):46.

9. Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis.

European journal of rheumatology. 2017 Mar;4(1):46.

10. Jia T, Byberg L, Lindholm B, Larsson TE, Lind L, Michaëlsson K, Carrero JJ. Dietary

acid load, kidney function, osteoporosis, and risk of fractures in elderly men and women.

Osteoporosis International. 2015 Feb 1;26(2):563-70.

11. National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrients | Nutrient Reference Values

[Internet]. Nrv.gov.au. 2019 [cited 25 September 2019]. Available from:

https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients.

12. Nutrition Australia. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Recommended daily intakes |

Nutrition Australia [Internet]. Nutritionaustralia.org. 2019 [cited 25 September 2019].

Available from: http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/resource/australian-dietary-

guidelines-recommended-daily-intakes.

13. Hsu PH, Lee CH, Kuo LK, Kung YC, Chen WJ, Tzeng MS. Higher energy and protein

intake from enteral nutrition may reduce hospital mortality in mechanically ventilated

critically ill elderly patients. International Journal of Gerontology. 2018 Dec 1;12(4):285-

9.

14. Cerri AP, Bellelli G, Mazzone A, Pittella F, Landi F, Zambon A, Annoni G. Sarcopenia

and malnutrition in acutely ill hospitalized elderly: Prevalence and outcomes. Clinical

nutrition. 2015 Aug 1;34(4):745-51.

8. Li G, Thabane L, Papaioannou A, Ioannidis G, Levine MA, Adachi JD. An overview of

osteoporosis and frailty in the elderly. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017

Dec;18(1):46.

9. Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis.

European journal of rheumatology. 2017 Mar;4(1):46.

10. Jia T, Byberg L, Lindholm B, Larsson TE, Lind L, Michaëlsson K, Carrero JJ. Dietary

acid load, kidney function, osteoporosis, and risk of fractures in elderly men and women.

Osteoporosis International. 2015 Feb 1;26(2):563-70.

11. National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrients | Nutrient Reference Values

[Internet]. Nrv.gov.au. 2019 [cited 25 September 2019]. Available from:

https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients.

12. Nutrition Australia. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Recommended daily intakes |

Nutrition Australia [Internet]. Nutritionaustralia.org. 2019 [cited 25 September 2019].

Available from: http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/resource/australian-dietary-

guidelines-recommended-daily-intakes.

13. Hsu PH, Lee CH, Kuo LK, Kung YC, Chen WJ, Tzeng MS. Higher energy and protein

intake from enteral nutrition may reduce hospital mortality in mechanically ventilated

critically ill elderly patients. International Journal of Gerontology. 2018 Dec 1;12(4):285-

9.

14. Cerri AP, Bellelli G, Mazzone A, Pittella F, Landi F, Zambon A, Annoni G. Sarcopenia

and malnutrition in acutely ill hospitalized elderly: Prevalence and outcomes. Clinical

nutrition. 2015 Aug 1;34(4):745-51.

11LIFESPAN NUTRITION

15. Samari B, Farid P, Ghapanvari MR, Mahmoudi Z. Factors associated with malnutrition in

the elderly. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2019;11(1):1009-14.

16. Eshkoor S, Hamid T, Shahar S, Ng C, Mun C. Factors affecting hypertension among the

Malaysian elderly. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease. 2016 Mar;3(1):8.

17. Lelli D, Antonelli-Incalzi R, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Pedone C. Association between

sodium excretion and cardiovascular disease and mortality in the elderly: a cohort study.

Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018 Mar 1;19(3):229-34.

18. Blekkenhorst LC, Prince RL, Hodgson JM, Lim WH, Zhu K, Devine A, Thompson PL,

Lewis JR. Dietary saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic vascular disease mortality in

elderly women: a prospective cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition.

2015 Jun 1;101(6):1263-8.

19. Praagman J, de Jonge EA, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Beulens JW, Sluijs I, Schoufour JD,

Hofman A, van der Schouw YT, Franco OH. Dietary saturated fatty acids and coronary

heart disease risk in a Dutch middle-aged and elderly population. Arteriosclerosis,

thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2016 Sep;36(9):2011-8.

20. de Oliveira PA, Kovacs C, Moreira P, Magnoni D, Saleh MH, Faintuch J. Unsaturated

fatty acids improve atherosclerosis markers in obese and overweight non-diabetic elderly

patients. Obesity surgery. 2017 Oct 1;27(10):2663-71.

21. Medina-Remón A, Tresserra-Rimbau A, Pons A, Tur JA, Martorell M, Ros E, Buil-

Cosiales P, Sacanella E, Covas MI, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J. Effects of total dietary

polyphenols on plasma nitric oxide and blood pressure in a high cardiovascular risk

cohort. The PREDIMED randomized trial. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular

Diseases. 2015 Jan 1;25(1):60-7.

15. Samari B, Farid P, Ghapanvari MR, Mahmoudi Z. Factors associated with malnutrition in

the elderly. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2019;11(1):1009-14.

16. Eshkoor S, Hamid T, Shahar S, Ng C, Mun C. Factors affecting hypertension among the

Malaysian elderly. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease. 2016 Mar;3(1):8.

17. Lelli D, Antonelli-Incalzi R, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Pedone C. Association between

sodium excretion and cardiovascular disease and mortality in the elderly: a cohort study.

Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018 Mar 1;19(3):229-34.

18. Blekkenhorst LC, Prince RL, Hodgson JM, Lim WH, Zhu K, Devine A, Thompson PL,

Lewis JR. Dietary saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic vascular disease mortality in

elderly women: a prospective cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition.

2015 Jun 1;101(6):1263-8.

19. Praagman J, de Jonge EA, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Beulens JW, Sluijs I, Schoufour JD,

Hofman A, van der Schouw YT, Franco OH. Dietary saturated fatty acids and coronary

heart disease risk in a Dutch middle-aged and elderly population. Arteriosclerosis,

thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2016 Sep;36(9):2011-8.

20. de Oliveira PA, Kovacs C, Moreira P, Magnoni D, Saleh MH, Faintuch J. Unsaturated

fatty acids improve atherosclerosis markers in obese and overweight non-diabetic elderly

patients. Obesity surgery. 2017 Oct 1;27(10):2663-71.

21. Medina-Remón A, Tresserra-Rimbau A, Pons A, Tur JA, Martorell M, Ros E, Buil-

Cosiales P, Sacanella E, Covas MI, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J. Effects of total dietary

polyphenols on plasma nitric oxide and blood pressure in a high cardiovascular risk

cohort. The PREDIMED randomized trial. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular

Diseases. 2015 Jan 1;25(1):60-7.

12LIFESPAN NUTRITION

22. Bolland MJ, Leung W, Tai V, Bastin S, Gamble GD, Grey A, Reid IR. Calcium intake

and risk of fracture: systematic review. Bmj. 2015 Sep 29;351:h4580.

23. Bougioukli S, Κollia P, Koromila T, Varitimidis S, Hantes M, Karachalios T, Malizos

ΚΝ, Dailiana ZH. Failure in diagnosis and under-treatment of osteoporosis in elderly

patients with fragility fractures. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2019 Mar

15;37(2):327-35.

24. Oberle CD, Samaghabadi RO, Hughes EM. Orthorexia nervosa: Assessment and

correlates with gender, BMI, and personality. Appetite. 2017 Jan 1;108:303-10.

25. 10. Dietitians Association of Australia. Orthorexia: The unhealthy side of healthy eating

– Dietitians Association of Australia [Internet]. Daa.asn.au. 2019 [cited 25 September

2019]. Available from:

https://daa.asn.au/smart-eating-for-you/smart-eating-fast-facts/medical/orthorexia-the-

unhealthy-side-of-healthy-eating/

26. Lagast S, De Pelsmaeker S, Schouteten J, Gellynck X. Local food products in health care

facilities: Elderly sensory acceptance of a local food menu. In11th Pangborn Sensory

Science symposium 2015.

27. Aziz NA, Teng NI, Hamid MR, Ismail NH. Assessing the nutritional status of

hospitalized elderly. Clinical interventions in aging. 2017;12:1615.

28. Cichero JA. Adjustment of food textural properties for elderly patients. Journal of texture

studies. 2016 Aug;47(4):277-83.

29. Fernández‐Barrés S, Martin N, Canela T, García‐Barco M, Basora J, Arija V, Project

ATDOM‐NUT group. Dietary intake in the dependent elderly: evaluation of the risk of

nutritional deficit. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016 Apr;29(2):174-84.

22. Bolland MJ, Leung W, Tai V, Bastin S, Gamble GD, Grey A, Reid IR. Calcium intake

and risk of fracture: systematic review. Bmj. 2015 Sep 29;351:h4580.

23. Bougioukli S, Κollia P, Koromila T, Varitimidis S, Hantes M, Karachalios T, Malizos

ΚΝ, Dailiana ZH. Failure in diagnosis and under-treatment of osteoporosis in elderly

patients with fragility fractures. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2019 Mar

15;37(2):327-35.

24. Oberle CD, Samaghabadi RO, Hughes EM. Orthorexia nervosa: Assessment and

correlates with gender, BMI, and personality. Appetite. 2017 Jan 1;108:303-10.

25. 10. Dietitians Association of Australia. Orthorexia: The unhealthy side of healthy eating

– Dietitians Association of Australia [Internet]. Daa.asn.au. 2019 [cited 25 September

2019]. Available from:

https://daa.asn.au/smart-eating-for-you/smart-eating-fast-facts/medical/orthorexia-the-

unhealthy-side-of-healthy-eating/

26. Lagast S, De Pelsmaeker S, Schouteten J, Gellynck X. Local food products in health care

facilities: Elderly sensory acceptance of a local food menu. In11th Pangborn Sensory

Science symposium 2015.

27. Aziz NA, Teng NI, Hamid MR, Ismail NH. Assessing the nutritional status of

hospitalized elderly. Clinical interventions in aging. 2017;12:1615.

28. Cichero JA. Adjustment of food textural properties for elderly patients. Journal of texture

studies. 2016 Aug;47(4):277-83.

29. Fernández‐Barrés S, Martin N, Canela T, García‐Barco M, Basora J, Arija V, Project

ATDOM‐NUT group. Dietary intake in the dependent elderly: evaluation of the risk of

nutritional deficit. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016 Apr;29(2):174-84.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

13LIFESPAN NUTRITION

30. Flores TR, Nunes BP, Assunção MC, Bertoldi AD. Healthy habits: what kind of guidance

the elderly population is receiving from health professionals?. Revista Brasileira de

Epidemiologia. 2016 Mar;19(1):167-80.

31. Blekkenhorst LC, Prince RL, Hodgson JM, Lim WH, Zhu K, Devine A, Thompson PL,

Lewis JR. Dietary saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic vascular disease mortality in

elderly women: a prospective cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition.

2015 Jun 1;101(6):1263-8.

.

30. Flores TR, Nunes BP, Assunção MC, Bertoldi AD. Healthy habits: what kind of guidance

the elderly population is receiving from health professionals?. Revista Brasileira de

Epidemiologia. 2016 Mar;19(1):167-80.

31. Blekkenhorst LC, Prince RL, Hodgson JM, Lim WH, Zhu K, Devine A, Thompson PL,

Lewis JR. Dietary saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic vascular disease mortality in

elderly women: a prospective cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition.

2015 Jun 1;101(6):1263-8.

.

1 out of 14

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.