Reconceptualizing rhetorical practices in organizations: The impact of social media on internal communications

Write a report on a chosen topic in Business Communications, demonstrating a comprehensive understanding, research skills, critical analysis, and effective communication methods.

13 Pages16535 Words485 Views

Added on 2023-06-10

About This Document

This article explores the effects of social media on established and emerging flows of rhetorical practices in organizations, focusing on the expanding roles played by senior management and employees. The authors examine the use of social media in three multinational organizations in the telecommunications industry, revealing that social media enable and facilitate the shaping of organizational rhetorical practices by adding multivocality, increasing reach and richness in communication, and enabling simultaneous consumption and co-production of rhetorical content.

Reconceptualizing rhetorical practices in organizations: The impact of social media on internal communications

Write a report on a chosen topic in Business Communications, demonstrating a comprehensive understanding, research skills, critical analysis, and effective communication methods.

Added on 2023-06-10

ShareRelated Documents

Reconceptualizing rhetorical practices in organizations: The impact of social

media on internal communications

Jimmy Huang a,

*, Joa ̃o Baptista a , Robert D. Galliers b

a Warwick Business School, The University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK

b Bentley University, 175 Forest Street, Waltham, MA 02452, USA

1. Introduction

Recent technological advances in intranet systems have shifted

organizational communication from conventional channels, such

as printed media, face-to-face interactions and email to such

company wide web-based platforms as these [7,38]. This shift has

recently been accelerated by the advent of social media which are

defined as ‘‘a group of Internet-based applications that build on the

ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that

allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content’’

[33,61]. While many organizations may only partially and

selectively incorporate certain aspects of the array of applications

and features available, the growing incorporation of social media in

organizations has led to a further significant reshaping of intra-

organizational communication [21,25,45]. While the intranet still

plays a major role as a centrally managed repository of ‘official’

information, various forms of social media, such as blogging and

wikis, have been introduced to allow employees to engage in

conversations across functions, regions and hierarchical levels

[39]. Two issues that emerge from this new trend are clear. First,

when incorporating social media into an organization’s communi-

cation, some adjustment in its usage is often required to fulfill the

organization’s communication needs and to comply with its

governance principles [6]. Such adjustments can potentially

provide a rich setting to extend our understanding of how social

media are used in different contexts. Second, social media

stimulate engagement, participation and exchange of information

[33,53] in a manner that can challenge established central control

of internal communication channels [14], thereby providing

another fertile research opportunity. Balmer [3] describes such

shifts as these by contrasting univocality with multivocality [4,64].

Balmer [3] refers to univocality as the control of what is often a

single source of voice that is legitimized by an organization to

present the organization and avoid ambiguity in the communicat-

ed messages and their intended meanings. Multivocality suggests

the fostering of a communication culture within which alternative

and multiple views can be freely voiced and contested. Even

though embracing multivocality through social media is not the

only way to enhance the strategic values of internal communica-

tion, multivocality, facilitated by social media, is believed to be

more beneficial than univocality in stimulating employees’

engagement and facilitating cross-functional innovation by

providing a means by which different ideas, viewpoints and

concerns are freely expressed, effectively exchanged, consulted

and consolidated [3,64]. One of the most important questions for

senior management raised by Balmer [3] is whether they should

retain control by pursuing univocality or loosen their grip on

discourse by embracing social media and multivocality.

Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 23 May 2012

Received in revised form 10 September 2012

Accepted 4 November 2012

Available online 11 November 2012

Keywords:

Rhetorical practices

Intra-organizational communication

Social media

Interpretive

Multiple case study research

A B S T R A C T

While intranets have become a central information hub for employees in different parts of an

organization, they have also played a key role as a rhetorical tool for senior managers. With the advent of

social media, this is increasingly so. How such technologies as these are incorporated into organizations’

‘rhetorical practices’ is an important, yet under-researched topic. To explore this research agenda, we

examine the effects of social media on established and emerging flows of rhetorical practices in

organizations, focusing in particular on the expanding, and in some cases switching, roles played by

senior management and employees. We conceptualize organizational rhetorical practices as the

combination of strategic intent, message and media, and discuss the interplay between rhetors and their

audience. Adopting an interpretive, multiple case study approach, we study the use of social media in

three multi-national organizations in the telecommunications industry. Our findings reveal that social

media enable and facilitate the shaping of organizational rhetorical practices by (i) adding multivocality;

(ii) increasing reach and richness in communication, and (iii) enabling simultaneous consumption and

co-production of rhetorical content.

ß 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 2476528201.

E-mail address: jimmy.huang@wbs.ac.uk (J. Huang).

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Information & Management

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i m

0378-7206/$ – see front matter ß 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2012.11.003

media on internal communications

Jimmy Huang a,

*, Joa ̃o Baptista a , Robert D. Galliers b

a Warwick Business School, The University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK

b Bentley University, 175 Forest Street, Waltham, MA 02452, USA

1. Introduction

Recent technological advances in intranet systems have shifted

organizational communication from conventional channels, such

as printed media, face-to-face interactions and email to such

company wide web-based platforms as these [7,38]. This shift has

recently been accelerated by the advent of social media which are

defined as ‘‘a group of Internet-based applications that build on the

ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that

allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content’’

[33,61]. While many organizations may only partially and

selectively incorporate certain aspects of the array of applications

and features available, the growing incorporation of social media in

organizations has led to a further significant reshaping of intra-

organizational communication [21,25,45]. While the intranet still

plays a major role as a centrally managed repository of ‘official’

information, various forms of social media, such as blogging and

wikis, have been introduced to allow employees to engage in

conversations across functions, regions and hierarchical levels

[39]. Two issues that emerge from this new trend are clear. First,

when incorporating social media into an organization’s communi-

cation, some adjustment in its usage is often required to fulfill the

organization’s communication needs and to comply with its

governance principles [6]. Such adjustments can potentially

provide a rich setting to extend our understanding of how social

media are used in different contexts. Second, social media

stimulate engagement, participation and exchange of information

[33,53] in a manner that can challenge established central control

of internal communication channels [14], thereby providing

another fertile research opportunity. Balmer [3] describes such

shifts as these by contrasting univocality with multivocality [4,64].

Balmer [3] refers to univocality as the control of what is often a

single source of voice that is legitimized by an organization to

present the organization and avoid ambiguity in the communicat-

ed messages and their intended meanings. Multivocality suggests

the fostering of a communication culture within which alternative

and multiple views can be freely voiced and contested. Even

though embracing multivocality through social media is not the

only way to enhance the strategic values of internal communica-

tion, multivocality, facilitated by social media, is believed to be

more beneficial than univocality in stimulating employees’

engagement and facilitating cross-functional innovation by

providing a means by which different ideas, viewpoints and

concerns are freely expressed, effectively exchanged, consulted

and consolidated [3,64]. One of the most important questions for

senior management raised by Balmer [3] is whether they should

retain control by pursuing univocality or loosen their grip on

discourse by embracing social media and multivocality.

Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 23 May 2012

Received in revised form 10 September 2012

Accepted 4 November 2012

Available online 11 November 2012

Keywords:

Rhetorical practices

Intra-organizational communication

Social media

Interpretive

Multiple case study research

A B S T R A C T

While intranets have become a central information hub for employees in different parts of an

organization, they have also played a key role as a rhetorical tool for senior managers. With the advent of

social media, this is increasingly so. How such technologies as these are incorporated into organizations’

‘rhetorical practices’ is an important, yet under-researched topic. To explore this research agenda, we

examine the effects of social media on established and emerging flows of rhetorical practices in

organizations, focusing in particular on the expanding, and in some cases switching, roles played by

senior management and employees. We conceptualize organizational rhetorical practices as the

combination of strategic intent, message and media, and discuss the interplay between rhetors and their

audience. Adopting an interpretive, multiple case study approach, we study the use of social media in

three multi-national organizations in the telecommunications industry. Our findings reveal that social

media enable and facilitate the shaping of organizational rhetorical practices by (i) adding multivocality;

(ii) increasing reach and richness in communication, and (iii) enabling simultaneous consumption and

co-production of rhetorical content.

ß 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 2476528201.

E-mail address: jimmy.huang@wbs.ac.uk (J. Huang).

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Information & Management

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i m

0378-7206/$ – see front matter ß 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2012.11.003

Cheney et al. [11] highlight the importance of research in this

general topic area and argue that the tension between univocality

and multivocality has had an impact on various aspects of

organizational communication. They see this impact as being

particularly apparent in the rhetorical practices in organizations.

To establish the conceptual grounding for our research, we

incorporate two of the prior accounts [11,48] and define rhetorical

practices as ‘‘embodied, materially mediated arrays of human

activity’’ [48, p. 2] of using persuasive language for the purposes of

negotiating, obtaining and sustaining support and consensus [11].

Rhetorical practices represent a key aspect of management and

leadership in any organization [11]. Notwithstanding the growing

importance of rhetorical practices and associated communication

technologies – in this case social media – for organizations, Huang

and Galliers [27] suggest that our understanding of this

phenomenon is still lacking and call for more research in this

arena. The rationale underpinning the examination of organiza-

tional rhetorical practices and social media in conjunction is

twofold. First, the potential of social media to revolutionize the

very basis of communication has rapidly become a reality

[22,33,39]. Without taking into account the influence of social

media, we run the risk of under-theorizing their influence on

organizational rhetorical practices. Second, while the need for

adjustment when adopting social media in organizational contexts

has been recognized [6], how such adjustments may facilitate

rhetorical practices, and how rhetorical practices may influence

the use made of social media, are yet to be explored. The current

research is therefore an attempt to improve our understanding of

the influence of social media on rhetorical practices within

organizational contexts.

The structure of the paper is as follows. We first conceptualize

rhetorical practices in the context of organizational communica-

tion. With this as background, we review the use of social media in

corporate intranets. Having explained the methods underpinning

our research, we provide empirical details of the three cases

depicting the dynamic interplay amongst the various conceptual

components of rhetorical practices in the organizations studied.

We then compare and contrast our findings with the current

literature to establish our theoretical contribution – in particular a

reconceptualization of existing models of rhetoric with a view to

incorporating the effects of social media on internal communica-

tions in organizations. We conclude by identifying theoretical and

practical implications of our research.

2. Conceptual foundations

Rhetoric represents ‘‘the humanistic tradition for the study of

persuasion’’ [11, p. 79]. While rhetoric is common to all types of

communication, in an organizational context, rhetoric is used with

specific intent, often to negotiate, generate and reinforce consen-

sus in situations of uncertainty and emerging possibilities

[23,50,51,56]. Organizational rhetorical practices are not merely

the mechanism that helps to establish and maintain consensus in

times of uncertainty and ambiguity [12,50,62], they also symbolize

the ‘‘logics of human relations’’ [11], serving a constitutive function

in shaping institutional change [19,56]. With these underlying

theoretical concepts in mind, it should be noted that, while rhetoric

and rhetoric practices are essentially a distinctive form of

communication, not all communications are deployed for rhetori-

cal purposes [12]. This distinction serves as a crucial conceptual

boundary in the way in which we frame our research and establish

our theoretical foundation.

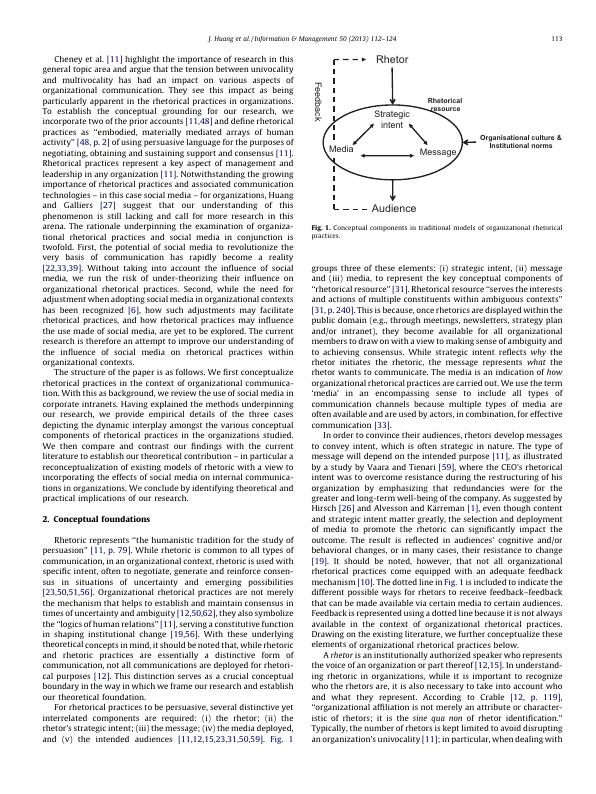

For rhetorical practices to be persuasive, several distinctive yet

interrelated components are required: (i) the rhetor; (ii) the

rhetor’s strategic intent; (iii) the message; (iv) the media deployed,

and (v) the intended audiences [11,12,15,23,31,50,59]. Fig. 1

groups three of these elements: (i) strategic intent, (ii) message

and (iii) media, to represent the key conceptual components of

‘‘rhetorical resource’’ [31]. Rhetorical resource ‘‘serves the interests

and actions of multiple constituents within ambiguous contexts’’

[31, p. 240]. This is because, once rhetorics are displayed within the

public domain (e.g., through meetings, newsletters, strategy plan

and/or intranet), they become available for all organizational

members to draw on with a view to making sense of ambiguity and

to achieving consensus. While strategic intent reflects why the

rhetor initiates the rhetoric, the message represents what the

rhetor wants to communicate. The media is an indication of how

organizational rhetorical practices are carried out. We use the term

‘media’ in an encompassing sense to include all types of

communication channels because multiple types of media are

often available and are used by actors, in combination, for effective

communication [33].

In order to convince their audiences, rhetors develop messages

to convey intent, which is often strategic in nature. The type of

message will depend on the intended purpose [11], as illustrated

by a study by Vaara and Tienari [59], where the CEO’s rhetorical

intent was to overcome resistance during the restructuring of his

organization by emphasizing that redundancies were for the

greater and long-term well-being of the company. As suggested by

Hirsch [26] and Alvesson and Ka ̈ rreman [1], even though content

and strategic intent matter greatly, the selection and deployment

of media to promote the rhetoric can significantly impact the

outcome. The result is reflected in audiences’ cognitive and/or

behavioral changes, or in many cases, their resistance to change

[19]. It should be noted, however, that not all organizational

rhetorical practices come equipped with an adequate feedback

mechanism [10]. The dotted line in Fig. 1 is included to indicate the

different possible ways for rhetors to receive feedback–feedback

that can be made available via certain media to certain audiences.

Feedback is represented using a dotted line because it is not always

available in the context of organizational rhetorical practices.

Drawing on the existing literature, we further conceptualize these

elements of organizational rhetorical practices below.

A rhetor is an institutionally authorized speaker who represents

the voice of an organization or part thereof [12,15]. In understand-

ing rhetoric in organizations, while it is important to recognize

who the rhetors are, it is also necessary to take into account who

and what they represent. According to Crable [12, p. 119],

‘‘organizational affiliation is not merely an attribute or character-

istic of rhetors; it is the sine qua non of rhetor identification.’’

Typically, the number of rhetors is kept limited to avoid disrupting

an organization’s univocality [11]; in particular, when dealing with

Rhetor

Audience

Message

Strategic

intent

Media

Feedback

Organisational culture &

Institutional norms

Rhetorical

resource

Fig. 1. Conceptual components in traditional models of organizational rhetorical

practices.

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124 113

general topic area and argue that the tension between univocality

and multivocality has had an impact on various aspects of

organizational communication. They see this impact as being

particularly apparent in the rhetorical practices in organizations.

To establish the conceptual grounding for our research, we

incorporate two of the prior accounts [11,48] and define rhetorical

practices as ‘‘embodied, materially mediated arrays of human

activity’’ [48, p. 2] of using persuasive language for the purposes of

negotiating, obtaining and sustaining support and consensus [11].

Rhetorical practices represent a key aspect of management and

leadership in any organization [11]. Notwithstanding the growing

importance of rhetorical practices and associated communication

technologies – in this case social media – for organizations, Huang

and Galliers [27] suggest that our understanding of this

phenomenon is still lacking and call for more research in this

arena. The rationale underpinning the examination of organiza-

tional rhetorical practices and social media in conjunction is

twofold. First, the potential of social media to revolutionize the

very basis of communication has rapidly become a reality

[22,33,39]. Without taking into account the influence of social

media, we run the risk of under-theorizing their influence on

organizational rhetorical practices. Second, while the need for

adjustment when adopting social media in organizational contexts

has been recognized [6], how such adjustments may facilitate

rhetorical practices, and how rhetorical practices may influence

the use made of social media, are yet to be explored. The current

research is therefore an attempt to improve our understanding of

the influence of social media on rhetorical practices within

organizational contexts.

The structure of the paper is as follows. We first conceptualize

rhetorical practices in the context of organizational communica-

tion. With this as background, we review the use of social media in

corporate intranets. Having explained the methods underpinning

our research, we provide empirical details of the three cases

depicting the dynamic interplay amongst the various conceptual

components of rhetorical practices in the organizations studied.

We then compare and contrast our findings with the current

literature to establish our theoretical contribution – in particular a

reconceptualization of existing models of rhetoric with a view to

incorporating the effects of social media on internal communica-

tions in organizations. We conclude by identifying theoretical and

practical implications of our research.

2. Conceptual foundations

Rhetoric represents ‘‘the humanistic tradition for the study of

persuasion’’ [11, p. 79]. While rhetoric is common to all types of

communication, in an organizational context, rhetoric is used with

specific intent, often to negotiate, generate and reinforce consen-

sus in situations of uncertainty and emerging possibilities

[23,50,51,56]. Organizational rhetorical practices are not merely

the mechanism that helps to establish and maintain consensus in

times of uncertainty and ambiguity [12,50,62], they also symbolize

the ‘‘logics of human relations’’ [11], serving a constitutive function

in shaping institutional change [19,56]. With these underlying

theoretical concepts in mind, it should be noted that, while rhetoric

and rhetoric practices are essentially a distinctive form of

communication, not all communications are deployed for rhetori-

cal purposes [12]. This distinction serves as a crucial conceptual

boundary in the way in which we frame our research and establish

our theoretical foundation.

For rhetorical practices to be persuasive, several distinctive yet

interrelated components are required: (i) the rhetor; (ii) the

rhetor’s strategic intent; (iii) the message; (iv) the media deployed,

and (v) the intended audiences [11,12,15,23,31,50,59]. Fig. 1

groups three of these elements: (i) strategic intent, (ii) message

and (iii) media, to represent the key conceptual components of

‘‘rhetorical resource’’ [31]. Rhetorical resource ‘‘serves the interests

and actions of multiple constituents within ambiguous contexts’’

[31, p. 240]. This is because, once rhetorics are displayed within the

public domain (e.g., through meetings, newsletters, strategy plan

and/or intranet), they become available for all organizational

members to draw on with a view to making sense of ambiguity and

to achieving consensus. While strategic intent reflects why the

rhetor initiates the rhetoric, the message represents what the

rhetor wants to communicate. The media is an indication of how

organizational rhetorical practices are carried out. We use the term

‘media’ in an encompassing sense to include all types of

communication channels because multiple types of media are

often available and are used by actors, in combination, for effective

communication [33].

In order to convince their audiences, rhetors develop messages

to convey intent, which is often strategic in nature. The type of

message will depend on the intended purpose [11], as illustrated

by a study by Vaara and Tienari [59], where the CEO’s rhetorical

intent was to overcome resistance during the restructuring of his

organization by emphasizing that redundancies were for the

greater and long-term well-being of the company. As suggested by

Hirsch [26] and Alvesson and Ka ̈ rreman [1], even though content

and strategic intent matter greatly, the selection and deployment

of media to promote the rhetoric can significantly impact the

outcome. The result is reflected in audiences’ cognitive and/or

behavioral changes, or in many cases, their resistance to change

[19]. It should be noted, however, that not all organizational

rhetorical practices come equipped with an adequate feedback

mechanism [10]. The dotted line in Fig. 1 is included to indicate the

different possible ways for rhetors to receive feedback–feedback

that can be made available via certain media to certain audiences.

Feedback is represented using a dotted line because it is not always

available in the context of organizational rhetorical practices.

Drawing on the existing literature, we further conceptualize these

elements of organizational rhetorical practices below.

A rhetor is an institutionally authorized speaker who represents

the voice of an organization or part thereof [12,15]. In understand-

ing rhetoric in organizations, while it is important to recognize

who the rhetors are, it is also necessary to take into account who

and what they represent. According to Crable [12, p. 119],

‘‘organizational affiliation is not merely an attribute or character-

istic of rhetors; it is the sine qua non of rhetor identification.’’

Typically, the number of rhetors is kept limited to avoid disrupting

an organization’s univocality [11]; in particular, when dealing with

Rhetor

Audience

Message

Strategic

intent

Media

Feedback

Organisational culture &

Institutional norms

Rhetorical

resource

Fig. 1. Conceptual components in traditional models of organizational rhetorical

practices.

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124 113

external audiences, such as in branding [24] and crisis manage-

ment [2]. Organizations limit the number of rhetors to enable

senior management to retain control of communication and avoid

alternative voices challenging and undermining authority [10,51].

However, by limiting the number of voices, organizations hinder

the exchange of different perspectives [50] and wider representa-

tion of diverse interests, especially in the context of innovation and

change [23,41,50] and empowerment [14].

As Balmer [3] and Cheney et al. [11] argue, the tension between

univocality and multivocality can be a trade-off for many

organizations. This is because the two represent an ‘either-or’

decision to which management has to commit. Maintaining both is

traditionally viewed as not being viable because, once organiza-

tions allow multiple voices to be heard, they immediately lose

control over the dominant discourse within the organization.

However, ultimately, the flow and variety of communication is

influenced by the institutional norms and culture of the

organization in which they are embedded [5,31,62]. While this

point is raised by Balmer [3] and Cheney et al. [11], they do not

account for the effects resulting from the alternative approaches

which management might consider in managing the trade-off. For

instance, can organizations simultaneously benefit from univo-

cality and multivocality? If so, what are the factors and

mechanisms which allow organizations to do so? Our study

addresses both of these questions.

A message with strategic intent refers to a rhetor’s representation

of a rhetorical situation by which (s)he aims to persuade an

audience. According to Crable [12, p. 120], ‘‘rhetors who actually

represent purely their own views may be extinct, if they ever

existed. Instead, rhetors speak for, or represent, certain—some-

times multiple, overlapping, or complementary—‘organized inter-

ests’.’’ One of the key functions of the message is to achieve

consensus by providing the intended audience with a ‘‘transcen-

dental big picture’’ or a ‘‘simplified and understandable official

view’’ to guide the way by which they can make sense of

circumstances and take action as a result [50]. Hence, what

underpins the message construction process is not just the

strategic intent of the rhetor and the selection of suitable media,

but also the cultural assumptions and institutionalized norms on

which he/she draws. As noted by Cheney et al. [11], rhetoric

‘‘reproduces and reinforces the cultural assumption on which it is

based’’.

Sillince [50] suggests that different messages, and in many

cases their effective blending and ordering, are required to

leverage different strategic intents. Cheney et al. [11] categorize

strategic intent in four areas: (i) responding to the contingencies/

uncertainties that the organization is encountering; (ii) anticipat-

ing future situations and emphasizing the need to address them

(e.g., [59]); (iii) changing or modifying the audiences’ ‘framing’ to

make sense of what is going on (e.g., [32]), and (iv) shaping and

sustaining an organization’s identity (e.g., [52]). Due to the

intertwining of the message and the strategic intent embedded

in it, each cannot be examined in isolation.

Media is the vehicle by which a message is delivered to certain

audiences, and through which feedback may be provided back to

the rhetor. Different media have the potential to be more or less

useful in particular rhetorical situations [11]. The selection of

suitable media depends on the content of the message and the

rhetor’s strategic intent, as well as on the relationship and extent to

which there is shared understanding between rhetor and intended

audience [59]. Specifically, the rhetor needs to take into account

the media’s ability to reach target audiences, and the degree of

richness that the media can provide. According to Evans and

Wurster [20], reach refers to the number of potential audiences to

be targeted at any one point in time, while the level of richness is

viewed as three interrelated elements, namely: (i) the ability to

accommodate the bandwidth of the message; (ii) the ability to

customize the message, and (iii) the level of interactivity that can

be mobilized during the communication. They propose that the

relationship between reach and richness is a trade-off that the

rhetor has to consider. In other words, when the message is

developed for broader reach, its richness may be compromised,

and vice versa.

Even though conventional channels, such as via paper, email,

and face-to-face communication, remain important for communi-

cating in organizations, intranets have gradually been adding to

such channels as these. Intranets are often used for strategic

purposes – to reinforce key corporate values; policies; strategy and

culture, for example – through text; sound; images and video, as

well as through page layouts; designs; branding, and navigations

[7]. Intranets also enable wider reach across organizations and

facilitate knowledge sharing and the building of communities of

practice (e.g., [8,54,60]). They can in some cases, however, be

developed with insufficient capacity to permit customization and

facilitate interactivity. They can also lead to unintended con-

sequences [46], such as the creation of ‘‘electronic fences’’ –

barriers to communication in other words [42]. Organizations have

recently started to incorporate social media as additional services

on their intranets, capitalizing on the participative and interactive

nature of these new tools [9,34]. One of the opportunities sought

by organizations is to use social media to increase reach, without

compromising on richness, as had been the case with traditional

media.

Audiences and their feedback is one of the key challenges in

managing internal communication in organizations because of the

complex, inconsistent and potentially conflicting nature of

feedback. As noted by Crable [12, p. 118], ‘‘just as rhetors’ realities

are inseparable from their organizational affiliation, the same may

be said of their audiences: Any ‘one’ audience member may have

several or many organizational identifications which, while

sometimes overlapping or conflicting in interests, all help define

that individual’’. Organizational rhetorical practices may therefore

have contradictory effects, such as in fostering behavioral and

cognitive change [51], while at the same time encouraging

resistance to change and dissent [19,56].

The role of feedback depends on the media used to carry the

rhetorical message. For instance, such media as corporate reports

and mission statements do not have an intrinsic feedback

mechanism. Indeed, it is often the case that organizations do

not provide formalized feedback mechanisms for their audiences.

Cheney and McMillan [10, pp. 98–99] comment on the legitimacy

of informal responses by suggesting that ‘‘the rhetorical predica-

ment of organizational members who rely largely on informal

messages to respond to the formal pronouncements of a

hierarchical organization: because their efforts are not authorized

by the organization, the members lack organizational legitimacy in

their attempts to persuade.’’

Feedback is valuable for rhetors because they can sense how

effective their rhetoric has been, but at the same time it is difficult

to manage and can at times generate unintended consequences

and potentially undermine the strategic intent of the message.

Ultimately it can destabilize institutionalized beliefs by allowing

alternative voices to compete for domination with the official view

[31,56]. Hence, the selection and design of the feedback mecha-

nism represents two choices commonly available to a rhetor [57].

The first choice is to create the rhetoric for the audiences’ passive

consumption. To do so, it is crucial for the rhetor to insert control

hoping that the audiences will understand and interpret the

rhetoric as intended. The second choice is a more participative

approach than the first one by engaging audiences in real debate

and the co-construction of the rhetoric. Often, the choice made by

the rhetor also reflects an organization’s rhetorical culture [6] and

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124114

ment [2]. Organizations limit the number of rhetors to enable

senior management to retain control of communication and avoid

alternative voices challenging and undermining authority [10,51].

However, by limiting the number of voices, organizations hinder

the exchange of different perspectives [50] and wider representa-

tion of diverse interests, especially in the context of innovation and

change [23,41,50] and empowerment [14].

As Balmer [3] and Cheney et al. [11] argue, the tension between

univocality and multivocality can be a trade-off for many

organizations. This is because the two represent an ‘either-or’

decision to which management has to commit. Maintaining both is

traditionally viewed as not being viable because, once organiza-

tions allow multiple voices to be heard, they immediately lose

control over the dominant discourse within the organization.

However, ultimately, the flow and variety of communication is

influenced by the institutional norms and culture of the

organization in which they are embedded [5,31,62]. While this

point is raised by Balmer [3] and Cheney et al. [11], they do not

account for the effects resulting from the alternative approaches

which management might consider in managing the trade-off. For

instance, can organizations simultaneously benefit from univo-

cality and multivocality? If so, what are the factors and

mechanisms which allow organizations to do so? Our study

addresses both of these questions.

A message with strategic intent refers to a rhetor’s representation

of a rhetorical situation by which (s)he aims to persuade an

audience. According to Crable [12, p. 120], ‘‘rhetors who actually

represent purely their own views may be extinct, if they ever

existed. Instead, rhetors speak for, or represent, certain—some-

times multiple, overlapping, or complementary—‘organized inter-

ests’.’’ One of the key functions of the message is to achieve

consensus by providing the intended audience with a ‘‘transcen-

dental big picture’’ or a ‘‘simplified and understandable official

view’’ to guide the way by which they can make sense of

circumstances and take action as a result [50]. Hence, what

underpins the message construction process is not just the

strategic intent of the rhetor and the selection of suitable media,

but also the cultural assumptions and institutionalized norms on

which he/she draws. As noted by Cheney et al. [11], rhetoric

‘‘reproduces and reinforces the cultural assumption on which it is

based’’.

Sillince [50] suggests that different messages, and in many

cases their effective blending and ordering, are required to

leverage different strategic intents. Cheney et al. [11] categorize

strategic intent in four areas: (i) responding to the contingencies/

uncertainties that the organization is encountering; (ii) anticipat-

ing future situations and emphasizing the need to address them

(e.g., [59]); (iii) changing or modifying the audiences’ ‘framing’ to

make sense of what is going on (e.g., [32]), and (iv) shaping and

sustaining an organization’s identity (e.g., [52]). Due to the

intertwining of the message and the strategic intent embedded

in it, each cannot be examined in isolation.

Media is the vehicle by which a message is delivered to certain

audiences, and through which feedback may be provided back to

the rhetor. Different media have the potential to be more or less

useful in particular rhetorical situations [11]. The selection of

suitable media depends on the content of the message and the

rhetor’s strategic intent, as well as on the relationship and extent to

which there is shared understanding between rhetor and intended

audience [59]. Specifically, the rhetor needs to take into account

the media’s ability to reach target audiences, and the degree of

richness that the media can provide. According to Evans and

Wurster [20], reach refers to the number of potential audiences to

be targeted at any one point in time, while the level of richness is

viewed as three interrelated elements, namely: (i) the ability to

accommodate the bandwidth of the message; (ii) the ability to

customize the message, and (iii) the level of interactivity that can

be mobilized during the communication. They propose that the

relationship between reach and richness is a trade-off that the

rhetor has to consider. In other words, when the message is

developed for broader reach, its richness may be compromised,

and vice versa.

Even though conventional channels, such as via paper, email,

and face-to-face communication, remain important for communi-

cating in organizations, intranets have gradually been adding to

such channels as these. Intranets are often used for strategic

purposes – to reinforce key corporate values; policies; strategy and

culture, for example – through text; sound; images and video, as

well as through page layouts; designs; branding, and navigations

[7]. Intranets also enable wider reach across organizations and

facilitate knowledge sharing and the building of communities of

practice (e.g., [8,54,60]). They can in some cases, however, be

developed with insufficient capacity to permit customization and

facilitate interactivity. They can also lead to unintended con-

sequences [46], such as the creation of ‘‘electronic fences’’ –

barriers to communication in other words [42]. Organizations have

recently started to incorporate social media as additional services

on their intranets, capitalizing on the participative and interactive

nature of these new tools [9,34]. One of the opportunities sought

by organizations is to use social media to increase reach, without

compromising on richness, as had been the case with traditional

media.

Audiences and their feedback is one of the key challenges in

managing internal communication in organizations because of the

complex, inconsistent and potentially conflicting nature of

feedback. As noted by Crable [12, p. 118], ‘‘just as rhetors’ realities

are inseparable from their organizational affiliation, the same may

be said of their audiences: Any ‘one’ audience member may have

several or many organizational identifications which, while

sometimes overlapping or conflicting in interests, all help define

that individual’’. Organizational rhetorical practices may therefore

have contradictory effects, such as in fostering behavioral and

cognitive change [51], while at the same time encouraging

resistance to change and dissent [19,56].

The role of feedback depends on the media used to carry the

rhetorical message. For instance, such media as corporate reports

and mission statements do not have an intrinsic feedback

mechanism. Indeed, it is often the case that organizations do

not provide formalized feedback mechanisms for their audiences.

Cheney and McMillan [10, pp. 98–99] comment on the legitimacy

of informal responses by suggesting that ‘‘the rhetorical predica-

ment of organizational members who rely largely on informal

messages to respond to the formal pronouncements of a

hierarchical organization: because their efforts are not authorized

by the organization, the members lack organizational legitimacy in

their attempts to persuade.’’

Feedback is valuable for rhetors because they can sense how

effective their rhetoric has been, but at the same time it is difficult

to manage and can at times generate unintended consequences

and potentially undermine the strategic intent of the message.

Ultimately it can destabilize institutionalized beliefs by allowing

alternative voices to compete for domination with the official view

[31,56]. Hence, the selection and design of the feedback mecha-

nism represents two choices commonly available to a rhetor [57].

The first choice is to create the rhetoric for the audiences’ passive

consumption. To do so, it is crucial for the rhetor to insert control

hoping that the audiences will understand and interpret the

rhetoric as intended. The second choice is a more participative

approach than the first one by engaging audiences in real debate

and the co-construction of the rhetoric. Often, the choice made by

the rhetor also reflects an organization’s rhetorical culture [6] and

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124114

its institutionalized norms [5], which are there to be used as

references but more importantly to be contested [31].

While prior studies review the effects of social media in

organizations, there is as yet little understanding concerning its

effects on internal communication, specifically on its effects on the

ability of senior executives to persuade and manage staff. We

contend that existing conceptualizations of rhetorical practices in

organizations do not fully capture the dynamic role that social

media can play in organizational communication, nor – more

specifically – the role of feedback in this context. Summarizing, the

literature suggests that organizations face three key trade-offs

when deciding how to enact rhetorical practices by using different

and often mixed channels; they need to consider a choice between

(i) ‘univocality’ and ‘multivocality’; (ii) ‘reach’ and ‘richness’, and

(iii) controlled ‘consumption’ and more participative modes of

rhetoric ‘development’. However, some literature also suggests

that the use of social media offers the possibility to break with

these trade-offs, allowing for greater reach and richness, while

being both a passive consumer and a contributor. While we are

interested in exploring how the incorporation of social media in an

organization’s intranet influences different components of rhetor-

ical practices, individually and collectively, we also seek to learn

how social media can potentially alter the decisions made about

the trade-offs identified above. With the overarching aim of

exploring ‘how the incorporation of social media in an organiza-

tion’s intranet influences the different components of organiza-

tional rhetorical practices’ in mind, the following section depicts

our methodological design and considerations to unravel this

question.

3. Research method

This particular study is part of an on-going research initiative

aimed at examining the development, usage and governance of

intranets in large multi-national organizations in high velocity

industries [17,18], such as financial services and telecommunica-

tions [5–7]. It focuses on three organizations in the telecommu-

nications industry, and explores the impacts of social media on the

rhetorical practices in these organizations.

3.1. Research design

We adopted an interpretive, multiple case study approach

because of its strengths in exploring research phenomena that

are relational in their construction and subjective in their sense-

making [61]. Our aim was to enrich the existing theoretical

landscape of organizational rhetorical practices by incorporating

the effects of social media into our inquiry. With this objective

in mind, the set of conceptual components, critically reviewed

and synthesized in Fig. 1, served as the ‘‘sensitizing device’’ [35]

to frame our research, guide our data collection, and facilitate its

analysis and interpretation [44].

The three organizations were selected given their extensive use

of digital media as a platform for internal communication and

collaboration. Although all three organizations used social media

to some extent, there were distinctive features regarding their use

in each organization. While one case organization allowed open

participation through blogs, wikis and other social media tools, the

other two organizations restricted publishing rights and main-

tained central control. Such variations not only permit us to

challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions about how social

media might be used in an organizational context, but also enable a

comparison of different approaches in the adoption and incorpo-

ration of social media, and of the impacts arising from its use on

each organization’s rhetorical practices.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

Data collection was divided into two distinctive yet connected

phases. The first consisted of exploring the functionalities, general

usage and governance of the intranet in the three organizations.

The initial emphasis was placed on understanding the structure,

rationale and control that each organization used to manage its

intranet environment, and aimed at establishing an overall

understanding of the context of each case organization with a

specific emphasis on its intranet usage. As a result of the data

collected from the initial phase, we were able to narrow down our

foci onto: (i) organizational rhetorical practices, instead of general

usage of intranet, and (ii) the impacts of the social media being

used. These newly revised foci were helpful to assist us in framing

our research in a more focused manner. Specifically, the diverse

landscape of organizational rhetorical practices characterized by

each case forced us to identify common conceptual elements

across all cases, so that meaningful comparison amongst them

could be generated. For instance, different roles enacted by

organizational members engaged in the rhetorical practices,

intents behind their engagements and approaches that they

deployed to actualize their intents were identified as some of these

key conceptual elements. These conceptual elements formed the

basis for us to examine and make sense of the impacts of social

media that we have already observed. Also, these conceptual

elements were useful pointers in informing us as to what further

empirical evidence would be required in our later phase of data

collection. The iterative process, in particular between our revised

foci, data collection and emerging findings [16,44], also enabled us

to refine our conceptual framework.

Based on the refined conceptual framework, we examined, in

the second phase, the flows and landscape of organizational

rhetorical practices within each case organization. Specifically, we

investigated the ways in which the use of social media were

organized, encouraged – and in one case, implicitly discouraged –

governed and embedded into the day-to-day functioning of the

organizations, thereby shaping and reshaping the social reality of

rhetorical practices. To do so, we emphasized the articulation of

individuals’ insights and experiences toward the use of social

media, their direct and indirect involvements in organizational

rhetorical practices and the changes arising from their social media

usage. The focus of the second phase was to collect sufficient

empirical evidence to depict the emerging conceptual framework

and use this framework to interpret, in a highly iterative manner,

the data we had collected [44]. During the second phase, we

conducted a total of 30 semi-structured interviews with different

stakeholders in the three organizations, including a sample of

employees who were users of the intranet and social media tools,

as well as managers. Appendix 1 provides a list of the roles and

positions of the people interviewed in each organization.

Each interview normally lasted between 1 and 2 h, and

consisted of two parts. Initially, discussion was fairly open, and

dealt with the evolution of, and services available for, internal

communication. This was followed by a second, more structured

part, which focused on key themes related to organizational

rhetorical practices, as conceptualized in Fig. 1. While the first part

of the interview was geared toward capturing insights related to

intranet usage and the trajectory of change, the second aimed to

encourage interviewees to reflect on their personal experiences

and observations about the impacts of social media on organiza-

tional communication and organizational rhetorical practices.

Screenshots, such as webpages and blog posts from each

organization’s intranet, were collected. For each organization, an

average of approximately 100 screenshots was collected. More-

over, documentation, including governance and strategy docu-

ments and steering group meeting minutes, were reviewed and

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124 115

references but more importantly to be contested [31].

While prior studies review the effects of social media in

organizations, there is as yet little understanding concerning its

effects on internal communication, specifically on its effects on the

ability of senior executives to persuade and manage staff. We

contend that existing conceptualizations of rhetorical practices in

organizations do not fully capture the dynamic role that social

media can play in organizational communication, nor – more

specifically – the role of feedback in this context. Summarizing, the

literature suggests that organizations face three key trade-offs

when deciding how to enact rhetorical practices by using different

and often mixed channels; they need to consider a choice between

(i) ‘univocality’ and ‘multivocality’; (ii) ‘reach’ and ‘richness’, and

(iii) controlled ‘consumption’ and more participative modes of

rhetoric ‘development’. However, some literature also suggests

that the use of social media offers the possibility to break with

these trade-offs, allowing for greater reach and richness, while

being both a passive consumer and a contributor. While we are

interested in exploring how the incorporation of social media in an

organization’s intranet influences different components of rhetor-

ical practices, individually and collectively, we also seek to learn

how social media can potentially alter the decisions made about

the trade-offs identified above. With the overarching aim of

exploring ‘how the incorporation of social media in an organiza-

tion’s intranet influences the different components of organiza-

tional rhetorical practices’ in mind, the following section depicts

our methodological design and considerations to unravel this

question.

3. Research method

This particular study is part of an on-going research initiative

aimed at examining the development, usage and governance of

intranets in large multi-national organizations in high velocity

industries [17,18], such as financial services and telecommunica-

tions [5–7]. It focuses on three organizations in the telecommu-

nications industry, and explores the impacts of social media on the

rhetorical practices in these organizations.

3.1. Research design

We adopted an interpretive, multiple case study approach

because of its strengths in exploring research phenomena that

are relational in their construction and subjective in their sense-

making [61]. Our aim was to enrich the existing theoretical

landscape of organizational rhetorical practices by incorporating

the effects of social media into our inquiry. With this objective

in mind, the set of conceptual components, critically reviewed

and synthesized in Fig. 1, served as the ‘‘sensitizing device’’ [35]

to frame our research, guide our data collection, and facilitate its

analysis and interpretation [44].

The three organizations were selected given their extensive use

of digital media as a platform for internal communication and

collaboration. Although all three organizations used social media

to some extent, there were distinctive features regarding their use

in each organization. While one case organization allowed open

participation through blogs, wikis and other social media tools, the

other two organizations restricted publishing rights and main-

tained central control. Such variations not only permit us to

challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions about how social

media might be used in an organizational context, but also enable a

comparison of different approaches in the adoption and incorpo-

ration of social media, and of the impacts arising from its use on

each organization’s rhetorical practices.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

Data collection was divided into two distinctive yet connected

phases. The first consisted of exploring the functionalities, general

usage and governance of the intranet in the three organizations.

The initial emphasis was placed on understanding the structure,

rationale and control that each organization used to manage its

intranet environment, and aimed at establishing an overall

understanding of the context of each case organization with a

specific emphasis on its intranet usage. As a result of the data

collected from the initial phase, we were able to narrow down our

foci onto: (i) organizational rhetorical practices, instead of general

usage of intranet, and (ii) the impacts of the social media being

used. These newly revised foci were helpful to assist us in framing

our research in a more focused manner. Specifically, the diverse

landscape of organizational rhetorical practices characterized by

each case forced us to identify common conceptual elements

across all cases, so that meaningful comparison amongst them

could be generated. For instance, different roles enacted by

organizational members engaged in the rhetorical practices,

intents behind their engagements and approaches that they

deployed to actualize their intents were identified as some of these

key conceptual elements. These conceptual elements formed the

basis for us to examine and make sense of the impacts of social

media that we have already observed. Also, these conceptual

elements were useful pointers in informing us as to what further

empirical evidence would be required in our later phase of data

collection. The iterative process, in particular between our revised

foci, data collection and emerging findings [16,44], also enabled us

to refine our conceptual framework.

Based on the refined conceptual framework, we examined, in

the second phase, the flows and landscape of organizational

rhetorical practices within each case organization. Specifically, we

investigated the ways in which the use of social media were

organized, encouraged – and in one case, implicitly discouraged –

governed and embedded into the day-to-day functioning of the

organizations, thereby shaping and reshaping the social reality of

rhetorical practices. To do so, we emphasized the articulation of

individuals’ insights and experiences toward the use of social

media, their direct and indirect involvements in organizational

rhetorical practices and the changes arising from their social media

usage. The focus of the second phase was to collect sufficient

empirical evidence to depict the emerging conceptual framework

and use this framework to interpret, in a highly iterative manner,

the data we had collected [44]. During the second phase, we

conducted a total of 30 semi-structured interviews with different

stakeholders in the three organizations, including a sample of

employees who were users of the intranet and social media tools,

as well as managers. Appendix 1 provides a list of the roles and

positions of the people interviewed in each organization.

Each interview normally lasted between 1 and 2 h, and

consisted of two parts. Initially, discussion was fairly open, and

dealt with the evolution of, and services available for, internal

communication. This was followed by a second, more structured

part, which focused on key themes related to organizational

rhetorical practices, as conceptualized in Fig. 1. While the first part

of the interview was geared toward capturing insights related to

intranet usage and the trajectory of change, the second aimed to

encourage interviewees to reflect on their personal experiences

and observations about the impacts of social media on organiza-

tional communication and organizational rhetorical practices.

Screenshots, such as webpages and blog posts from each

organization’s intranet, were collected. For each organization, an

average of approximately 100 screenshots was collected. More-

over, documentation, including governance and strategy docu-

ments and steering group meeting minutes, were reviewed and

J. Huang et al. / Information & Management 50 (2013) 112–124 115

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Social media: Influencing customer satisfaction in B2B saleslg...

|9

|11295

|60

From e-commerce to social commerce: A close look at design featureslg...

|14

|14996

|353

Public Relations Review Assignmentlg...

|11

|8770

|98

International Journal of Business Communicationlg...

|9

|2538

|19

Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizationslg...

|9

|9950

|418

Post 3: Summarise learning A strategic approach to businesslg...

|2

|444

|78