Measurement and Management of Unused Capacity in TDABC System

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/07

|75

|33738

|363

AI Summary

This paper discusses the measurement and management of unused capacity in a Time Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) System. It introduces the concepts of real and compulsory unused capacities per shift and explains how they can enhance the efficiency of the TDABC System. The paper also presents a case study of a hospital in Turkey to demonstrate the suggested solutions to the complexity of unused capacity.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

The Measurement and Management of Unused

Capacity in a Time Driven Activity Based Costing

System

Tanis, Veyis Naci; Özyapici, Hasan.Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research;

Clayton North Vol. 10, Iss. 2, (Summer 2012): 43-55.

1. Full text

2. Full text - PDF

3. Abstract/Details

4. References 23

Hide highlighting

Abstract

TranslateAbstract

Companies rendering continuous 24 hours a day service may encounter difficulties in

determining their unused capacity. In addressing this issue, managers can consider using a Time

Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) System. In the measurement of unused capacity,

managers should consider two new concepts, real and compulsory unused capacities. The aim

of this paper is, to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC System by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift. The principal result of the study is that the

number of employees to be dismissed or directed to other productive areas should be

determined on the basis of each shift, rather than considering the total amount of unused

capacity in a day/month for the whole of the company. Finally, the study concludes that the

management of unused capacity will only be effective when the real and compulsory unused

capacities per shift are considered. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT]

Full Text

TranslateFull text

Headnote

Abstract:

Companies rendering continuous 24 hours a day service may encounter difficulties in

determining their unused capacity. In addressing this issue, managers can consider using a Time

Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) System. In the measurement of unused capacity,

managers should consider two new concepts, real and compulsory unused capacities. The aim

of this paper is, to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC System by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift.

Capacity in a Time Driven Activity Based Costing

System

Tanis, Veyis Naci; Özyapici, Hasan.Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research;

Clayton North Vol. 10, Iss. 2, (Summer 2012): 43-55.

1. Full text

2. Full text - PDF

3. Abstract/Details

4. References 23

Hide highlighting

Abstract

TranslateAbstract

Companies rendering continuous 24 hours a day service may encounter difficulties in

determining their unused capacity. In addressing this issue, managers can consider using a Time

Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) System. In the measurement of unused capacity,

managers should consider two new concepts, real and compulsory unused capacities. The aim

of this paper is, to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC System by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift. The principal result of the study is that the

number of employees to be dismissed or directed to other productive areas should be

determined on the basis of each shift, rather than considering the total amount of unused

capacity in a day/month for the whole of the company. Finally, the study concludes that the

management of unused capacity will only be effective when the real and compulsory unused

capacities per shift are considered. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT]

Full Text

TranslateFull text

Headnote

Abstract:

Companies rendering continuous 24 hours a day service may encounter difficulties in

determining their unused capacity. In addressing this issue, managers can consider using a Time

Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) System. In the measurement of unused capacity,

managers should consider two new concepts, real and compulsory unused capacities. The aim

of this paper is, to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC System by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

The principal result of the study is that the number of employees to be dismissed or directed to

other productive areas should be determined on the basis of each shift, rather than considering

the total amount of unused capacity in a day/month for the whole of the company. Finally, the

study concludes that the management of unused capacity will only be effective when the real and

compulsory unused capacities per shiftare considered.

Keywords:

Time Driven Activity Based Costing

Activity Based Costing System

Unused Capacity

Real Unused Capacity

Compulsory Unused Capacity

(ProQuest: ... denotes formulae omitted.)

Introduction

In the current global environment, businesses are exposed to rapidly increasing competition and

are forced to enhance their competitive advantage in order to survive. As such, businesses must

apply an effective cost management system. There is much evidence that the Traditional Cost

System (TCS) can be considered a major obstacle to gaining a competitive advantage; due to

the fact that this system produces inaccurate information about the costs of goods and services.

This lead to the introduction of Activity Based Costing (ABC) and a simplified version of it called

Time Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) (see Ratnatunga and Waldmann, 2010, and the

literature quoted therein)

TDABC was developed due to implementation difficulties encountered in ABC. Kaplan and

Anderson (2007a) in proposing TDABC ensured an efficient cost system for businesses that was

also easy to implement (Pernot, et al., 2007). Kaplan and Anderson (2007a) also claimed that

this new cost system provides a significant competitive advantage to many companies. However,

TDABC has some significant shortcomings. The measurement of time is still problematic. This is

because, when direct observation is not possible, it uses the time estimations stated by

operatives (Gervais et al., 2010). Another significant shortcoming, discussed in this paper, is that

the TDABC has a significant issue regarding its interpretation of unused capacity, due to the

uncertainty surrounding this capacity. Unused capacity is clearly a complicated concept;

however, the uncertainty of unused capacity originates from the organisations' operations. Some

other productive areas should be determined on the basis of each shift, rather than considering

the total amount of unused capacity in a day/month for the whole of the company. Finally, the

study concludes that the management of unused capacity will only be effective when the real and

compulsory unused capacities per shiftare considered.

Keywords:

Time Driven Activity Based Costing

Activity Based Costing System

Unused Capacity

Real Unused Capacity

Compulsory Unused Capacity

(ProQuest: ... denotes formulae omitted.)

Introduction

In the current global environment, businesses are exposed to rapidly increasing competition and

are forced to enhance their competitive advantage in order to survive. As such, businesses must

apply an effective cost management system. There is much evidence that the Traditional Cost

System (TCS) can be considered a major obstacle to gaining a competitive advantage; due to

the fact that this system produces inaccurate information about the costs of goods and services.

This lead to the introduction of Activity Based Costing (ABC) and a simplified version of it called

Time Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) (see Ratnatunga and Waldmann, 2010, and the

literature quoted therein)

TDABC was developed due to implementation difficulties encountered in ABC. Kaplan and

Anderson (2007a) in proposing TDABC ensured an efficient cost system for businesses that was

also easy to implement (Pernot, et al., 2007). Kaplan and Anderson (2007a) also claimed that

this new cost system provides a significant competitive advantage to many companies. However,

TDABC has some significant shortcomings. The measurement of time is still problematic. This is

because, when direct observation is not possible, it uses the time estimations stated by

operatives (Gervais et al., 2010). Another significant shortcoming, discussed in this paper, is that

the TDABC has a significant issue regarding its interpretation of unused capacity, due to the

uncertainty surrounding this capacity. Unused capacity is clearly a complicated concept;

however, the uncertainty of unused capacity originates from the organisations' operations. Some

types of organisation such as service organisations giving a 24-hour, 365-day service, are more

problematic than others. This paper will focus on the uncertainty of the unused capacity itself

rather than focusing on the types of organisation or organisations' operations.

Eliminating a business's unused capacity is, in general, the best way for a manager to increase

its efficiency. However, unused capacity can never be fully eliminated due to its special

characteristics. This situation is most clearly seen in service companies rather than

manufacturing ones. Unlike most manufacturing companies, service companies, such as

hospitals, hotels, and certain restaurants, may render a 24 hours a day 7 days a week service. In

view of the fact that services in such industries are produced and consumed simultaneously, the

capacity utilisation of service companies directly depends on the demand of their customers. In

addition, since demands cannot be inventoried (Balanchandran et al., 2007), eliminating the

uncertainty of unused capacity becomes difficult for these types of companies.

Therefore, the ultimate purpose of this paper is not only to minimise the uncertainty of unused

capacity but also to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC system by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift. For this purpose, a case study was conducted

in a hospital located in the southern part of Turkey. Not only does this case study contribute to

our understanding of TDABC, but it also creates an effective example through which to formulate

effective decisions about the employment of the work force in the service sector.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Information about unused capacity is

presented and then numerical examples are given to express the uncertainty of unused capacity.

In an attempt to mitigate this uncertainty, a theoretical framework is created; and this framework

will be tested through a case study of a business in the service sector.

Predecessors of TDABC

In the current advanced business environment, labour-intensive production has been replaced by

capital-intensive production. As a result, the role of direct labour in manufacturing has also

reduced. As a result, applying TCS, which uses direct labour hour as an allocation base, has

been shown to produce distorted cost data (Gunasekaran and Sarhadi, 1998; Ratnatunga and

Waldmann, 2010).

It is evident that companies that use distorted cost data have little opportunity to compete with

their rivals. This has generated a need for a new cost system to protect and maintain a

competitive advantage. In addition, the new systems can assist and encourage innovations to be

realised in the organisations (Ostergren and Stensaker, 2011). This resulted in Activity Based

Costing (ABC). The ABC system provides more reliable and useful results than the TCS. This is

because the ABC system uses cost drivers to assign the cost of activities to products and

problematic than others. This paper will focus on the uncertainty of the unused capacity itself

rather than focusing on the types of organisation or organisations' operations.

Eliminating a business's unused capacity is, in general, the best way for a manager to increase

its efficiency. However, unused capacity can never be fully eliminated due to its special

characteristics. This situation is most clearly seen in service companies rather than

manufacturing ones. Unlike most manufacturing companies, service companies, such as

hospitals, hotels, and certain restaurants, may render a 24 hours a day 7 days a week service. In

view of the fact that services in such industries are produced and consumed simultaneously, the

capacity utilisation of service companies directly depends on the demand of their customers. In

addition, since demands cannot be inventoried (Balanchandran et al., 2007), eliminating the

uncertainty of unused capacity becomes difficult for these types of companies.

Therefore, the ultimate purpose of this paper is not only to minimise the uncertainty of unused

capacity but also to enhance the efficiency of the TDABC system by clarifying and explaining the

real and compulsory unused capacities per shift. For this purpose, a case study was conducted

in a hospital located in the southern part of Turkey. Not only does this case study contribute to

our understanding of TDABC, but it also creates an effective example through which to formulate

effective decisions about the employment of the work force in the service sector.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Information about unused capacity is

presented and then numerical examples are given to express the uncertainty of unused capacity.

In an attempt to mitigate this uncertainty, a theoretical framework is created; and this framework

will be tested through a case study of a business in the service sector.

Predecessors of TDABC

In the current advanced business environment, labour-intensive production has been replaced by

capital-intensive production. As a result, the role of direct labour in manufacturing has also

reduced. As a result, applying TCS, which uses direct labour hour as an allocation base, has

been shown to produce distorted cost data (Gunasekaran and Sarhadi, 1998; Ratnatunga and

Waldmann, 2010).

It is evident that companies that use distorted cost data have little opportunity to compete with

their rivals. This has generated a need for a new cost system to protect and maintain a

competitive advantage. In addition, the new systems can assist and encourage innovations to be

realised in the organisations (Ostergren and Stensaker, 2011). This resulted in Activity Based

Costing (ABC). The ABC system provides more reliable and useful results than the TCS. This is

because the ABC system uses cost drivers to assign the cost of activities to products and

services. Consequently, it recognises the relationship between cost drivers and activities and this

relationship helps managers analyse the causes of costs much more easily. Moreover, it

provides better information about the costs of activities, products and services, which helps to

improve the effectiveness of decision-making (Ellis- Newman and Robinson, 1998; Yennie,

1999). Companies such as Chrysler and Safety-Kleen have used ABC and improved the

accuracy of their cost measurements (Beheshti, 2004).

Despite its attractiveness, the ABC system encounters some significant problems.

Measurements and operational complexities may result in problems for ABC implementers, as

the ABC system requires estimations of the costs of activity pools as well as cost drivers. These

estimations of the nature of resource usage can cause measurement errors, which lead to less

accurate cost information (Bruggeman et al., 2005). Two other problems are the high costs of

conducting interviews, and the subjectivity of data used (particularly for time allocations)

(Lambino, 2007). In addition, the updating process of the system is problematic. Finally, this

system becomes theoretically inadequate when it does not take the possibility of unused capacity

into account Consequently, Kaplan and Anderson, (2007a) proposed TDABC as a revised model

of the ABC system; in order to create a more easily implementable and more effective and

reliable cost allocation system.

TDABC is a simple, yet effective way to approach business processes as it enables one to

produce comprehensive information about the costs of products and services (Kaplan and

Anderson, 2007b). It also provides businesses with an elegant, well-designed and practical

option for identifying the capacity utilisation of their processes; not to mention its aid in

determining the cost and profitability of their products and services. Moreover, the TDABC

enables organisations to enhance their cost management systems by gathering reliable and

adequate cost data (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a; Pernot et al., 2007). Unit costs of supplying

resources and the time needed to perform an activity by the resource group are the only two

factors used by the TDABC system. It is recommended that managers should also combine

standard costing to implement the TDABC allocation system successfully (Ratnatunga and

Waldmann, 2010). TDABC provides easy updating of the cost system, even in fast changing

environments (Everaert and Bruggeman, 2007; Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a). It also enhances

the applicability of cost management systems by recognising the unused capacity incurred by a

company (Tse and Gong, 2009). However, the uncertainty of unused capacity is still problematic

in TDABC. Thus, the structure of unused capacity should be considered to understand and

minimise its uncertainty.

Unused Capacity

relationship helps managers analyse the causes of costs much more easily. Moreover, it

provides better information about the costs of activities, products and services, which helps to

improve the effectiveness of decision-making (Ellis- Newman and Robinson, 1998; Yennie,

1999). Companies such as Chrysler and Safety-Kleen have used ABC and improved the

accuracy of their cost measurements (Beheshti, 2004).

Despite its attractiveness, the ABC system encounters some significant problems.

Measurements and operational complexities may result in problems for ABC implementers, as

the ABC system requires estimations of the costs of activity pools as well as cost drivers. These

estimations of the nature of resource usage can cause measurement errors, which lead to less

accurate cost information (Bruggeman et al., 2005). Two other problems are the high costs of

conducting interviews, and the subjectivity of data used (particularly for time allocations)

(Lambino, 2007). In addition, the updating process of the system is problematic. Finally, this

system becomes theoretically inadequate when it does not take the possibility of unused capacity

into account Consequently, Kaplan and Anderson, (2007a) proposed TDABC as a revised model

of the ABC system; in order to create a more easily implementable and more effective and

reliable cost allocation system.

TDABC is a simple, yet effective way to approach business processes as it enables one to

produce comprehensive information about the costs of products and services (Kaplan and

Anderson, 2007b). It also provides businesses with an elegant, well-designed and practical

option for identifying the capacity utilisation of their processes; not to mention its aid in

determining the cost and profitability of their products and services. Moreover, the TDABC

enables organisations to enhance their cost management systems by gathering reliable and

adequate cost data (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a; Pernot et al., 2007). Unit costs of supplying

resources and the time needed to perform an activity by the resource group are the only two

factors used by the TDABC system. It is recommended that managers should also combine

standard costing to implement the TDABC allocation system successfully (Ratnatunga and

Waldmann, 2010). TDABC provides easy updating of the cost system, even in fast changing

environments (Everaert and Bruggeman, 2007; Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a). It also enhances

the applicability of cost management systems by recognising the unused capacity incurred by a

company (Tse and Gong, 2009). However, the uncertainty of unused capacity is still problematic

in TDABC. Thus, the structure of unused capacity should be considered to understand and

minimise its uncertainty.

Unused Capacity

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Companies often minimise their limitations in an effort to increase efficiency. It is important to

note that recognising limitations may become very difficult for managers since it requires a

comprehensive investigation of all aspects, sections and processes of the company.

One of the major limitations of companies is unused capacity, which can be defined as the

difference between available resources and consumed resources (Tse and Gong, 2009). In other

words, unused capacity is the amount of capacity that is not employed in the primary activity of

the business (White, 2009). It is also important to note that unused capacity could be found, as

stated by Cooper and Kaplan (1992), by subtracting the 'activity usage' from the 'activity

availability'. Therefore, it provides the relationship between the costs of resources used and the

costs of resources supplied. The researchers will also emphasise that practical capacity is more

appropriate than theoretical capacity; therefore, practical capacity should be used in the

calculations of unused capacity. Nevertheless, the practical capacity concept is not

comprehensive enough to be used alone to minimise or eliminate the complexity of unused

capacity. This is because it does not indicate how many employees should be dismissed or

directed to other productive areas.

As well as disclosing other efficiency and effectiveness limitations, cost systems can be used to

expose a company's unused capacity.

This is because cost systems enable managers to recognise their existing situation as they

provide comprehensive information about the company. In this regard, a truly resource based

system helps companies to shape their strategies (Barsky and Marchant, 2000).

Unlike TDABC, the TCS is unable to identify the unused capacity, because the predetermined

overhead rates used in this system are calculated by dividing estimated or budgeted overhead

costs by the estimated total cost driver capacity such as direct labour hours. This practice results

in inefficient outcomes since the cost of unused capacity is assigned to products or services.

Similarly, the ABC system does not reveal the unused capacity since it assumes that employees

and other resources all work at full capacity (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a).

An accurate system could be used to show capacity utilisation, which provides the basis for the

planning and control activities (Bamford and Chatziaslan, 2009). Unlike TCS and ABC, the

TDABC system provides valuable information by disclosing the unused capacity. However, all

data gained through the TDABC system must be analysed in a more detailed way as certain

company policies, such as total daily service duration, may go unnoticed by the implementers of

the TDABC system. This is because the unused capacity is not separated into subdivisions by

this system. As a result, it becomes difficult for managers to thoroughly analyse unused capacity

in the interpretation process.

note that recognising limitations may become very difficult for managers since it requires a

comprehensive investigation of all aspects, sections and processes of the company.

One of the major limitations of companies is unused capacity, which can be defined as the

difference between available resources and consumed resources (Tse and Gong, 2009). In other

words, unused capacity is the amount of capacity that is not employed in the primary activity of

the business (White, 2009). It is also important to note that unused capacity could be found, as

stated by Cooper and Kaplan (1992), by subtracting the 'activity usage' from the 'activity

availability'. Therefore, it provides the relationship between the costs of resources used and the

costs of resources supplied. The researchers will also emphasise that practical capacity is more

appropriate than theoretical capacity; therefore, practical capacity should be used in the

calculations of unused capacity. Nevertheless, the practical capacity concept is not

comprehensive enough to be used alone to minimise or eliminate the complexity of unused

capacity. This is because it does not indicate how many employees should be dismissed or

directed to other productive areas.

As well as disclosing other efficiency and effectiveness limitations, cost systems can be used to

expose a company's unused capacity.

This is because cost systems enable managers to recognise their existing situation as they

provide comprehensive information about the company. In this regard, a truly resource based

system helps companies to shape their strategies (Barsky and Marchant, 2000).

Unlike TDABC, the TCS is unable to identify the unused capacity, because the predetermined

overhead rates used in this system are calculated by dividing estimated or budgeted overhead

costs by the estimated total cost driver capacity such as direct labour hours. This practice results

in inefficient outcomes since the cost of unused capacity is assigned to products or services.

Similarly, the ABC system does not reveal the unused capacity since it assumes that employees

and other resources all work at full capacity (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a).

An accurate system could be used to show capacity utilisation, which provides the basis for the

planning and control activities (Bamford and Chatziaslan, 2009). Unlike TCS and ABC, the

TDABC system provides valuable information by disclosing the unused capacity. However, all

data gained through the TDABC system must be analysed in a more detailed way as certain

company policies, such as total daily service duration, may go unnoticed by the implementers of

the TDABC system. This is because the unused capacity is not separated into subdivisions by

this system. As a result, it becomes difficult for managers to thoroughly analyse unused capacity

in the interpretation process.

A detailed examination of the unused capacity provides clarity as to whether the workforce

should be reduced or directed to other areas. Examples, which demonstrate the complexity of

unused capacity, will be presented in this section, and a case study will be discussed in a

subsequent section.

Before giving examples, it is also important to emphasise that formulations given in the paper are

created to eliminate complexity and to simplify the determination of unused capacity. These

formulations will also be used in the case study to display the suggested solutions to the

complexity of unused capacity.

Example 1: This example is given to illustrate the uncertainty of unused capacity:

Assuming that three or four receptionists are working in a hotel between 24.00-08.00 hours,

unused capacity may occur because of the arrival of a small number of customers during that

shift. On the other hand, when a group of people arrives at the hotel at the same time, the

number of employees, including receptionists and bellhops, may be too few to sustain an

adequate level of service.

It can be said that the uncertainty of unused capacity in the example above results from the

uncertainty of demand. Uncertainty is the state of having limited knowledge about a specific

topic, condition, or event; in other words, uncertainty is a situation arising when a manager or

employee cannot precisely determine or predict a specific event. As noted earlier, the unused

capacity can be considered to be the 'uncertain' element. The uncertainty of unused capacity

may result due to various reasons; of which four are listed here. Firstly, when events in a

company are not expected, unused capacity may occur. Secondly, the possibility of the

occurrence of extraordinary situations may result in the uncertainty of unused capacity. Thirdly,

when employee' behaviour does not match expectations, it will be difficult for them to perform

effectively. This can also result in the occurrence of unused capacity. The final but most

importantly, uncertainty of demand may result in the uncertainty of unused capacity. This is

because when a customer needs a product or service, he or she could request it at any moment

during a shift. Thus, there should be a minimum of one employee available during the shift. In

this respect, a lack of customers will cause unused capacity to occur. The uncertainty of unused

capacity affects both service and manufacturing industries, and it may lead to inadequate pricing

policies, which may be one of the main causes of customer dissatisfaction.

In order to maintain the balance between input and output flows, the service duration capacity

should be larger than the expected demand in service companies. Meanwhile, because of the

uncertainty of production time, a similar strategy may need to be implemented by manufacturing

companies (Balanchandran et al., 2007). For these types of situation, one way that managers

can make an efficient decision is to consider the unused capacity. This is because emphasising

should be reduced or directed to other areas. Examples, which demonstrate the complexity of

unused capacity, will be presented in this section, and a case study will be discussed in a

subsequent section.

Before giving examples, it is also important to emphasise that formulations given in the paper are

created to eliminate complexity and to simplify the determination of unused capacity. These

formulations will also be used in the case study to display the suggested solutions to the

complexity of unused capacity.

Example 1: This example is given to illustrate the uncertainty of unused capacity:

Assuming that three or four receptionists are working in a hotel between 24.00-08.00 hours,

unused capacity may occur because of the arrival of a small number of customers during that

shift. On the other hand, when a group of people arrives at the hotel at the same time, the

number of employees, including receptionists and bellhops, may be too few to sustain an

adequate level of service.

It can be said that the uncertainty of unused capacity in the example above results from the

uncertainty of demand. Uncertainty is the state of having limited knowledge about a specific

topic, condition, or event; in other words, uncertainty is a situation arising when a manager or

employee cannot precisely determine or predict a specific event. As noted earlier, the unused

capacity can be considered to be the 'uncertain' element. The uncertainty of unused capacity

may result due to various reasons; of which four are listed here. Firstly, when events in a

company are not expected, unused capacity may occur. Secondly, the possibility of the

occurrence of extraordinary situations may result in the uncertainty of unused capacity. Thirdly,

when employee' behaviour does not match expectations, it will be difficult for them to perform

effectively. This can also result in the occurrence of unused capacity. The final but most

importantly, uncertainty of demand may result in the uncertainty of unused capacity. This is

because when a customer needs a product or service, he or she could request it at any moment

during a shift. Thus, there should be a minimum of one employee available during the shift. In

this respect, a lack of customers will cause unused capacity to occur. The uncertainty of unused

capacity affects both service and manufacturing industries, and it may lead to inadequate pricing

policies, which may be one of the main causes of customer dissatisfaction.

In order to maintain the balance between input and output flows, the service duration capacity

should be larger than the expected demand in service companies. Meanwhile, because of the

uncertainty of production time, a similar strategy may need to be implemented by manufacturing

companies (Balanchandran et al., 2007). For these types of situation, one way that managers

can make an efficient decision is to consider the unused capacity. This is because emphasising

the unused capacity costs may lead to a reduction of unused capacity resources (Buchheit,

2003). In general, there are three major decisions that must be made. The first is to increase

organisational outputs or to reduce quantities of committed resources; i.e. organisations can

improve their operational efficiency by increasing the demand of customers or decreasing the

quantities of committed resources (Buchheit, 2003; Tse and Gong, 2009). The second is to

reduce the number of employees, although managers should always employ at least one

employee for each shift. It is also important to emphasise that dismissal of employees is not

desirable. Thus, if it is possible (if other departments need to recruit new staffand if employees to

be dismissed have the necessary qualifications that meet the requirements of these

departments), these employees can be employed in other departments of the company. The

other initiative is for managers to allow employees to direct their own unused capacities towards

other productive jobs. By doing this, when the demand of customers cannot be increased, the

negative effect of the unused capacity to be incurred is minimised. As a result, it can be said that

the examination of unused capacity per shiftmust be done accurately and effectively in order to

make the right decisions.

Example 2: This example is given to emphasise that a separate analysis of unused capacity

should be done for each shift.

Company X operates two shifts per day and the unused capacities in the first and second shifts

are 10,000 minutes and 12,000 minutes, respectively. If the practical capacity of an employee is

equal to 11,000 minutes, a manager who makes a general analysis can say that the total amount

of unused capacity is equal to the practical capacities of two employees (10,000 min + 12,000

min = 2*11,000 min) so two employees can be dismissed. However, when the analysis of unused

capacity is made on the basis of each shift, it can be said that only one employee should be

dismissed. Furthermore, the employee working in the first shiftshould be directed to perform

other more productive tasks. One employee could be dismissed from the second shift(since the

unused capacity is higher than the practical capacity of one employee) but an employee is

needed for the first shift(11,000 min - 10,000 min) requiring a total of 1,000 minutes.

When the example is analysed, it appears that a separate analysis of unused capacity should be

conducted for each shift. This is due to the fact that, in some circumstances, the unused capacity

of a single shiftmay become less than the practical capacity of an employee. However, if the total

amount of unused capacity for all shifts is considered, then that amount may easily become

higher than the practical capacity of the employee. This may lead to inappropriate decisions, as it

appears that the number of employees to be dismissed/ redeployed to other area is more than it

should be.

2003). In general, there are three major decisions that must be made. The first is to increase

organisational outputs or to reduce quantities of committed resources; i.e. organisations can

improve their operational efficiency by increasing the demand of customers or decreasing the

quantities of committed resources (Buchheit, 2003; Tse and Gong, 2009). The second is to

reduce the number of employees, although managers should always employ at least one

employee for each shift. It is also important to emphasise that dismissal of employees is not

desirable. Thus, if it is possible (if other departments need to recruit new staffand if employees to

be dismissed have the necessary qualifications that meet the requirements of these

departments), these employees can be employed in other departments of the company. The

other initiative is for managers to allow employees to direct their own unused capacities towards

other productive jobs. By doing this, when the demand of customers cannot be increased, the

negative effect of the unused capacity to be incurred is minimised. As a result, it can be said that

the examination of unused capacity per shiftmust be done accurately and effectively in order to

make the right decisions.

Example 2: This example is given to emphasise that a separate analysis of unused capacity

should be done for each shift.

Company X operates two shifts per day and the unused capacities in the first and second shifts

are 10,000 minutes and 12,000 minutes, respectively. If the practical capacity of an employee is

equal to 11,000 minutes, a manager who makes a general analysis can say that the total amount

of unused capacity is equal to the practical capacities of two employees (10,000 min + 12,000

min = 2*11,000 min) so two employees can be dismissed. However, when the analysis of unused

capacity is made on the basis of each shift, it can be said that only one employee should be

dismissed. Furthermore, the employee working in the first shiftshould be directed to perform

other more productive tasks. One employee could be dismissed from the second shift(since the

unused capacity is higher than the practical capacity of one employee) but an employee is

needed for the first shift(11,000 min - 10,000 min) requiring a total of 1,000 minutes.

When the example is analysed, it appears that a separate analysis of unused capacity should be

conducted for each shift. This is due to the fact that, in some circumstances, the unused capacity

of a single shiftmay become less than the practical capacity of an employee. However, if the total

amount of unused capacity for all shifts is considered, then that amount may easily become

higher than the practical capacity of the employee. This may lead to inappropriate decisions, as it

appears that the number of employees to be dismissed/ redeployed to other area is more than it

should be.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Example 3: This example illustrates that an analysis of unused capacity should be made by

considering the service durations of businesses:

Hotel BCD has ten receptionists. They work 2,240 hours per month (10 receptionists*8 hours per

day*28 days per month). If the receptionists spend 15% of their time on breaks and training, the

total practical capacity of them becomes 114,240 minutes per month (The total practical capacity

for each receptionist is 11,424 minutes). They need only 33,600 minutes for customers;

therefore, the unused capacity is equal to 80,640 minutes (114,240 min - 33,600 min). It seems

that three receptionists would suffice for this hotel since the practical capacity of three

receptionists (34,272 min) is higher than the minutes required by the task (33,600 min). If seven

receptionists are dismissed (10 receptionists - 3 receptionists, or 80,640 min/11,424 min),

inefficiency problems will occur since this number not only includes the employees who should

be dismissed from the hotel, but also the employees who should be retained and directed to

other areas in the hotel. Indeed, Hotel BCD provides a 24-hour service, so it needs a minimum of

43,200 minutes (30 days per month*24 hours per day*60 minutes per hour) per month. Thus, a

minimum of four receptionists (43,200 min/11,424 min = 3.78) is needed by the hotel. In view of

this, the important point here is that the implementers should recognise the service durations of

businesses.

In addition, each business may have to consider its own unique situation. To illustrate, if Hotel

BCD always renders 90% of its services between 08.00-12.00 hours, it will require more than

four receptionists within this period as a number of clients arriving at the same time may require

more than one receptionist to meet their needs. Analyses of shifts, therefore, become helpful for

managers to make strategic decisions.

To summarise, managers should primarily determine the required time for the sustainability of a

business service. They should also determine the required number of employees for each shiftby

analysing the intensity of their customers' demands. Finally, the evaluated unused times of

employees should be eliminated or should be directed to other areas to enhance the productivity

of the company.

Removing the Uncertainty of Unused Capacity: A Theoretical Framework

The uncertainty of unused capacity is a significant issue for many managers, yet they can solve

this problem by considering two new concepts created by the authors of this study: Real Unused

Capacity and Compulsory Unused Capacity. The description of constructs within the two

proposed concepts is as follows:

Practical Capacity (Pc): This represents the actual work duration. It can be calculated by

subtracting time for scheduled breaks, training, meetings, maintenance and other sources of

considering the service durations of businesses:

Hotel BCD has ten receptionists. They work 2,240 hours per month (10 receptionists*8 hours per

day*28 days per month). If the receptionists spend 15% of their time on breaks and training, the

total practical capacity of them becomes 114,240 minutes per month (The total practical capacity

for each receptionist is 11,424 minutes). They need only 33,600 minutes for customers;

therefore, the unused capacity is equal to 80,640 minutes (114,240 min - 33,600 min). It seems

that three receptionists would suffice for this hotel since the practical capacity of three

receptionists (34,272 min) is higher than the minutes required by the task (33,600 min). If seven

receptionists are dismissed (10 receptionists - 3 receptionists, or 80,640 min/11,424 min),

inefficiency problems will occur since this number not only includes the employees who should

be dismissed from the hotel, but also the employees who should be retained and directed to

other areas in the hotel. Indeed, Hotel BCD provides a 24-hour service, so it needs a minimum of

43,200 minutes (30 days per month*24 hours per day*60 minutes per hour) per month. Thus, a

minimum of four receptionists (43,200 min/11,424 min = 3.78) is needed by the hotel. In view of

this, the important point here is that the implementers should recognise the service durations of

businesses.

In addition, each business may have to consider its own unique situation. To illustrate, if Hotel

BCD always renders 90% of its services between 08.00-12.00 hours, it will require more than

four receptionists within this period as a number of clients arriving at the same time may require

more than one receptionist to meet their needs. Analyses of shifts, therefore, become helpful for

managers to make strategic decisions.

To summarise, managers should primarily determine the required time for the sustainability of a

business service. They should also determine the required number of employees for each shiftby

analysing the intensity of their customers' demands. Finally, the evaluated unused times of

employees should be eliminated or should be directed to other areas to enhance the productivity

of the company.

Removing the Uncertainty of Unused Capacity: A Theoretical Framework

The uncertainty of unused capacity is a significant issue for many managers, yet they can solve

this problem by considering two new concepts created by the authors of this study: Real Unused

Capacity and Compulsory Unused Capacity. The description of constructs within the two

proposed concepts is as follows:

Practical Capacity (Pc): This represents the actual work duration. It can be calculated by

subtracting time for scheduled breaks, training, meetings, maintenance and other sources of

downtime from the theoretical capacity (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007a). The main logic of the

theoretical capacity is that all personnel and equipment operate with utmost efficiency. In this

regard, the theoretical capacity is unrealistic since it does not consider normal interruptions due

to repairs, maintenance and scheduling fluctuations (Kaplan and Anderson, 2004). Furthermore,

it is unattainable because, in real life, employees need refreshment breaks. "The practical

capacity of one employee" and "the total practical capacity of all employees" realising the same

activities are denoted by c P and ct P , respectively.

Time Spent on a Task(Ts): This is the time spent by employees on a particular task. The required

times for each customer are totalled to calculate the time spent on a task. For example, if there

are a total of 50 customers (30 existing and 20 new) for Company X and an order from an

existing customer takes 10 minutes, and if a new customer needs an additional 2 minutes, then

the time spent on this task will be 540 minutes (30 existing customers*10 min + 20 new

customers*12 min). (Note that an important assumption of the study is that when time spent on a

task is higher than the shiftduration, there is always a minimum of one employee on duty during a

shift. It is also assumed that not all customers arrive at the same time, so time spent on a task

reflects the work done throughout the shift)

Time Required For a Task (Tr): This is the shifttime as stated by business policy. In other words,

it is the service duration of the company. If each shiftincludes only one worker, the service

duration (time required for a task) of a company may become higher than the time spent on a

task. If each shiftincludes more than one worker, the time spent on a task may become higher

than the service duration.

The two proposed concepts, Real Unused Capacity and Compulsory Unused Capacity, can now

be explained as follows:

Real Unused Capacity (Ruc): This is the actual unused capacity for a business. It shows the

number of employees who should be dismissed from the department. As an alternative to

dismissal, if other departments need to recruit new staffand if employees to be dismissed have

the necessary qualifications that meet the requirements of these departments, managers can

direct these employees to other departments of the company.

The real unused capacity is calculated by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee" by the

integer part of the decimal number. The decimal number is found by dividing the difference

between "total practical capacities of employees" and "time required for a task" by "practical

capacity of an employee".

theoretical capacity is that all personnel and equipment operate with utmost efficiency. In this

regard, the theoretical capacity is unrealistic since it does not consider normal interruptions due

to repairs, maintenance and scheduling fluctuations (Kaplan and Anderson, 2004). Furthermore,

it is unattainable because, in real life, employees need refreshment breaks. "The practical

capacity of one employee" and "the total practical capacity of all employees" realising the same

activities are denoted by c P and ct P , respectively.

Time Spent on a Task(Ts): This is the time spent by employees on a particular task. The required

times for each customer are totalled to calculate the time spent on a task. For example, if there

are a total of 50 customers (30 existing and 20 new) for Company X and an order from an

existing customer takes 10 minutes, and if a new customer needs an additional 2 minutes, then

the time spent on this task will be 540 minutes (30 existing customers*10 min + 20 new

customers*12 min). (Note that an important assumption of the study is that when time spent on a

task is higher than the shiftduration, there is always a minimum of one employee on duty during a

shift. It is also assumed that not all customers arrive at the same time, so time spent on a task

reflects the work done throughout the shift)

Time Required For a Task (Tr): This is the shifttime as stated by business policy. In other words,

it is the service duration of the company. If each shiftincludes only one worker, the service

duration (time required for a task) of a company may become higher than the time spent on a

task. If each shiftincludes more than one worker, the time spent on a task may become higher

than the service duration.

The two proposed concepts, Real Unused Capacity and Compulsory Unused Capacity, can now

be explained as follows:

Real Unused Capacity (Ruc): This is the actual unused capacity for a business. It shows the

number of employees who should be dismissed from the department. As an alternative to

dismissal, if other departments need to recruit new staffand if employees to be dismissed have

the necessary qualifications that meet the requirements of these departments, managers can

direct these employees to other departments of the company.

The real unused capacity is calculated by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee" by the

integer part of the decimal number. The decimal number is found by dividing the difference

between "total practical capacities of employees" and "time required for a task" by "practical

capacity of an employee".

However, "time required for a task" is changed with "time spent on a task" in the formulae when

the "time spent on a task" is higher than the "time required for a task". Real unused capacity can

take only integer values. It is always equal to multiples of the practical capacity of an employee.

Compulsory Unused Capacity (Cuc): This is mandatory unused capacity, and it is necessary for

the continuity of a business. Unlike real unused capacity, it shows the number of employees who

should be directed to other productive areas such as sending e-mails to customers regarding

reservation dates, informing customers about promotions, or any other job that is not listed in

their job descriptions.

Each business has its own policy on sales, promotion and distribution. One of the most important

policies of a business is the service duration policy. Regarding service duration, in general, many

businesses are divided into three different groups; businesses rendering 8, 16, or 24 hour

services. It is also important to emphasise that the service duration (capacity) should be larger

than the expected demand due to the uncertainty of demand (Balanchandran et al., 2007).

The compulsory unused capacity is calculated by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee"

by the decimal place of the decimal number. In addition, when the "time required for a task"

becomes higher than the "time spent on a task", the difference should be added to the value

found by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee" by the decimal place of the decimal

number. As is explained above, the decimal number is found by dividing the difference between

"total practical capacities of employees" and "time required for a task" by "practical capacity of an

employee". However, the "time required for a task" is changed with the "time spent on a task" in

the formulae when the "time spent on a task" is higher than the "time required for a task".

The Real and Compulsory Unused Capacities can be expressed in formulae as follows:

Assuming that Ts < Tr, then

Ruc = X* Pc

Where "Ruc" is the real unused capacity, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee, "X" is the

integer part of the decimal number. Consider a decimal number as X.abc where X is an integer

part and abc is a decimal place including the first three terms of the decimal number.

The decimal number can be found as:

...

the "time spent on a task" is higher than the "time required for a task". Real unused capacity can

take only integer values. It is always equal to multiples of the practical capacity of an employee.

Compulsory Unused Capacity (Cuc): This is mandatory unused capacity, and it is necessary for

the continuity of a business. Unlike real unused capacity, it shows the number of employees who

should be directed to other productive areas such as sending e-mails to customers regarding

reservation dates, informing customers about promotions, or any other job that is not listed in

their job descriptions.

Each business has its own policy on sales, promotion and distribution. One of the most important

policies of a business is the service duration policy. Regarding service duration, in general, many

businesses are divided into three different groups; businesses rendering 8, 16, or 24 hour

services. It is also important to emphasise that the service duration (capacity) should be larger

than the expected demand due to the uncertainty of demand (Balanchandran et al., 2007).

The compulsory unused capacity is calculated by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee"

by the decimal place of the decimal number. In addition, when the "time required for a task"

becomes higher than the "time spent on a task", the difference should be added to the value

found by multiplying "practical capacity of an employee" by the decimal place of the decimal

number. As is explained above, the decimal number is found by dividing the difference between

"total practical capacities of employees" and "time required for a task" by "practical capacity of an

employee". However, the "time required for a task" is changed with the "time spent on a task" in

the formulae when the "time spent on a task" is higher than the "time required for a task".

The Real and Compulsory Unused Capacities can be expressed in formulae as follows:

Assuming that Ts < Tr, then

Ruc = X* Pc

Where "Ruc" is the real unused capacity, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee, "X" is the

integer part of the decimal number. Consider a decimal number as X.abc where X is an integer

part and abc is a decimal place including the first three terms of the decimal number.

The decimal number can be found as:

...

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Where "Cuc" is the compulsory unused capacity, "Tr" is the time required for a task, "Ts" is the

time spent on a task, "abc" is a decimal place including the first three terms of the decimal

number, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee.

Assuming that Ts ≥ Tr, then:

Ruc = X* Pc

Where "Ruc" is the real unused capacity, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee, "X" is the

integer part of the decimal number.

Cuc = abc* Pc

Where "Cuc" is the compulsory unused capacity, "abc" is a decimal place including the first three

terms of the decimal number, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee.

When the formulae is analysed, it can be concluded that the total unused capacity, which

includes real and compulsory unused capacities, is equal to the difference between "total

practical capacity" and "time spent on a task". In this regard, this difference, which can be

considered as the proof of the formulae given below, is formulated as:

... (A)

The proof of the formulae (A) can be given as:

Assume that Ts < Tr then:

...

Total Unused Capacity = Pct - Ts

Assume that Ts ≥ Tr then:

...

Total Unused Capacity = Pct - Ts

The formulas demonstrate that without making a detailed analysis by separating unused capacity

as real or compulsory capacities, managers cannot make accurate decisions about how many

employees should be dismissed or directed to other, more productive areas. In view of this, the

efficiency of the formulas can be seen quite clearly in the following case study.

Case Study

time spent on a task, "abc" is a decimal place including the first three terms of the decimal

number, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee.

Assuming that Ts ≥ Tr, then:

Ruc = X* Pc

Where "Ruc" is the real unused capacity, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee, "X" is the

integer part of the decimal number.

Cuc = abc* Pc

Where "Cuc" is the compulsory unused capacity, "abc" is a decimal place including the first three

terms of the decimal number, "Pc" is the practical capacity of an employee.

When the formulae is analysed, it can be concluded that the total unused capacity, which

includes real and compulsory unused capacities, is equal to the difference between "total

practical capacity" and "time spent on a task". In this regard, this difference, which can be

considered as the proof of the formulae given below, is formulated as:

... (A)

The proof of the formulae (A) can be given as:

Assume that Ts < Tr then:

...

Total Unused Capacity = Pct - Ts

Assume that Ts ≥ Tr then:

...

Total Unused Capacity = Pct - Ts

The formulas demonstrate that without making a detailed analysis by separating unused capacity

as real or compulsory capacities, managers cannot make accurate decisions about how many

employees should be dismissed or directed to other, more productive areas. In view of this, the

efficiency of the formulas can be seen quite clearly in the following case study.

Case Study

As mentioned in the previous sections, unused capacity determination and employee

coordination become much more difficult in complex organisations. This complexity will be

clarified in a case study in combination with a theoretical framework. Firstly, the research method

will be summarised; following this, the case study will be presented.

Research Method

The method used in this study is a "Case Study". This method has been selected as it provides a

wide perspective for the research. The 24-hour service policy of hospitals helps to reveal the

importance of unused capacity examination; hence, a hospital was selected in order to increase

the validity of the study.

In this regard, a descriptive case study was first carried out to identify the current situation of the

hospital. Following this, an exploratory case study was conducted to evaluate the applicability of

the proposed concepts, where the aim is to minimise the uncertainty of the unused capacity of

secretaries in the hospital.

The researchers visited the hospital regularly to investigate the current working environment of

the secretaries. Thus, in this study, face-toface interviews with the hospital management and

secretaries were carried out, and comprehensive direct observations as well as documentation

collection were used as data collection methods. Accordingly, the daily practices of secretaries in

the hospital were analysed at least three times per month during the year 2010.

In addition to the observations and face-toface interviews, researchers were able to obtain a

significant amount of data through telephone calls with both the management and the

secretaries. The data collected were analysed as follows.

The Case Study Company

The Hospital Alfa (The management of the hospital asked the researcher not to use its real

name), where the case study was conducted, is a well-equipped private hospital which provides

a 24-hour emergency service for patients. It is located in Adana, which is a province in the

southern part of Turkey.

This study analyses the time spent by secretaries working in the General Surgery Department

only. An analysis of capacity costs at departmental level provides insights into whether or not

departmental managers are reacting effectively in response to market conditions (Yahya-Zadeh,

2011). Therefore, this study will facilitate the capacity management of the secretaries of the

General Surgery Department.

coordination become much more difficult in complex organisations. This complexity will be

clarified in a case study in combination with a theoretical framework. Firstly, the research method

will be summarised; following this, the case study will be presented.

Research Method

The method used in this study is a "Case Study". This method has been selected as it provides a

wide perspective for the research. The 24-hour service policy of hospitals helps to reveal the

importance of unused capacity examination; hence, a hospital was selected in order to increase

the validity of the study.

In this regard, a descriptive case study was first carried out to identify the current situation of the

hospital. Following this, an exploratory case study was conducted to evaluate the applicability of

the proposed concepts, where the aim is to minimise the uncertainty of the unused capacity of

secretaries in the hospital.

The researchers visited the hospital regularly to investigate the current working environment of

the secretaries. Thus, in this study, face-toface interviews with the hospital management and

secretaries were carried out, and comprehensive direct observations as well as documentation

collection were used as data collection methods. Accordingly, the daily practices of secretaries in

the hospital were analysed at least three times per month during the year 2010.

In addition to the observations and face-toface interviews, researchers were able to obtain a

significant amount of data through telephone calls with both the management and the

secretaries. The data collected were analysed as follows.

The Case Study Company

The Hospital Alfa (The management of the hospital asked the researcher not to use its real

name), where the case study was conducted, is a well-equipped private hospital which provides

a 24-hour emergency service for patients. It is located in Adana, which is a province in the

southern part of Turkey.

This study analyses the time spent by secretaries working in the General Surgery Department

only. An analysis of capacity costs at departmental level provides insights into whether or not

departmental managers are reacting effectively in response to market conditions (Yahya-Zadeh,

2011). Therefore, this study will facilitate the capacity management of the secretaries of the

General Surgery Department.

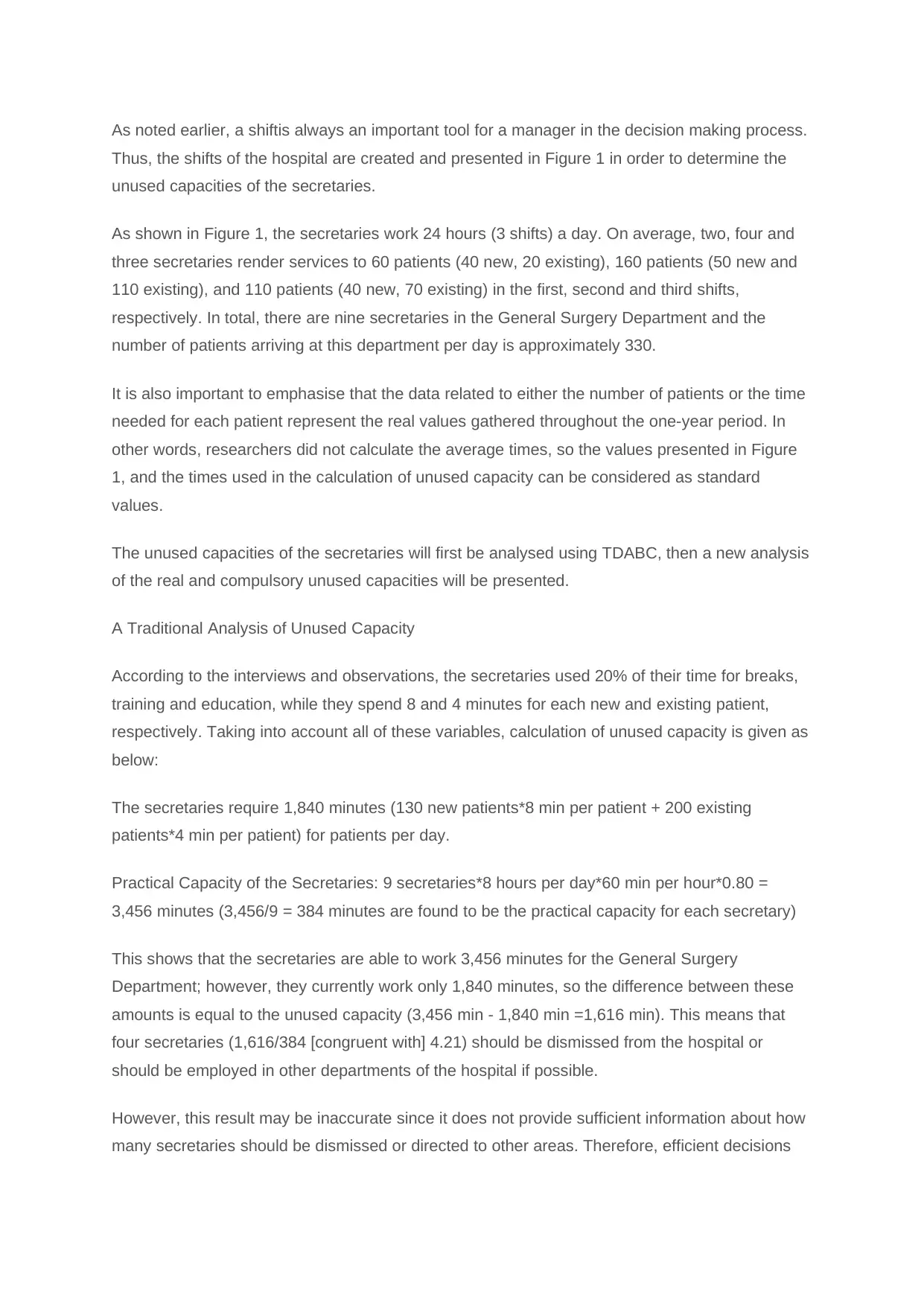

As noted earlier, a shiftis always an important tool for a manager in the decision making process.

Thus, the shifts of the hospital are created and presented in Figure 1 in order to determine the

unused capacities of the secretaries.

As shown in Figure 1, the secretaries work 24 hours (3 shifts) a day. On average, two, four and

three secretaries render services to 60 patients (40 new, 20 existing), 160 patients (50 new and

110 existing), and 110 patients (40 new, 70 existing) in the first, second and third shifts,

respectively. In total, there are nine secretaries in the General Surgery Department and the

number of patients arriving at this department per day is approximately 330.

It is also important to emphasise that the data related to either the number of patients or the time

needed for each patient represent the real values gathered throughout the one-year period. In

other words, researchers did not calculate the average times, so the values presented in Figure

1, and the times used in the calculation of unused capacity can be considered as standard

values.

The unused capacities of the secretaries will first be analysed using TDABC, then a new analysis

of the real and compulsory unused capacities will be presented.

A Traditional Analysis of Unused Capacity

According to the interviews and observations, the secretaries used 20% of their time for breaks,

training and education, while they spend 8 and 4 minutes for each new and existing patient,

respectively. Taking into account all of these variables, calculation of unused capacity is given as

below:

The secretaries require 1,840 minutes (130 new patients*8 min per patient + 200 existing

patients*4 min per patient) for patients per day.

Practical Capacity of the Secretaries: 9 secretaries*8 hours per day*60 min per hour*0.80 =

3,456 minutes (3,456/9 = 384 minutes are found to be the practical capacity for each secretary)

This shows that the secretaries are able to work 3,456 minutes for the General Surgery

Department; however, they currently work only 1,840 minutes, so the difference between these

amounts is equal to the unused capacity (3,456 min - 1,840 min =1,616 min). This means that

four secretaries (1,616/384 [congruent with] 4.21) should be dismissed from the hospital or

should be employed in other departments of the hospital if possible.

However, this result may be inaccurate since it does not provide sufficient information about how

many secretaries should be dismissed or directed to other areas. Therefore, efficient decisions

Thus, the shifts of the hospital are created and presented in Figure 1 in order to determine the

unused capacities of the secretaries.

As shown in Figure 1, the secretaries work 24 hours (3 shifts) a day. On average, two, four and

three secretaries render services to 60 patients (40 new, 20 existing), 160 patients (50 new and

110 existing), and 110 patients (40 new, 70 existing) in the first, second and third shifts,

respectively. In total, there are nine secretaries in the General Surgery Department and the

number of patients arriving at this department per day is approximately 330.

It is also important to emphasise that the data related to either the number of patients or the time

needed for each patient represent the real values gathered throughout the one-year period. In

other words, researchers did not calculate the average times, so the values presented in Figure

1, and the times used in the calculation of unused capacity can be considered as standard

values.

The unused capacities of the secretaries will first be analysed using TDABC, then a new analysis

of the real and compulsory unused capacities will be presented.

A Traditional Analysis of Unused Capacity

According to the interviews and observations, the secretaries used 20% of their time for breaks,

training and education, while they spend 8 and 4 minutes for each new and existing patient,

respectively. Taking into account all of these variables, calculation of unused capacity is given as

below:

The secretaries require 1,840 minutes (130 new patients*8 min per patient + 200 existing

patients*4 min per patient) for patients per day.

Practical Capacity of the Secretaries: 9 secretaries*8 hours per day*60 min per hour*0.80 =

3,456 minutes (3,456/9 = 384 minutes are found to be the practical capacity for each secretary)

This shows that the secretaries are able to work 3,456 minutes for the General Surgery

Department; however, they currently work only 1,840 minutes, so the difference between these

amounts is equal to the unused capacity (3,456 min - 1,840 min =1,616 min). This means that

four secretaries (1,616/384 [congruent with] 4.21) should be dismissed from the hospital or

should be employed in other departments of the hospital if possible.

However, this result may be inaccurate since it does not provide sufficient information about how

many secretaries should be dismissed or directed to other areas. Therefore, efficient decisions

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

about the work force cannot be made based on these data. As a result, a new combined model is

needed to improve efficiency.

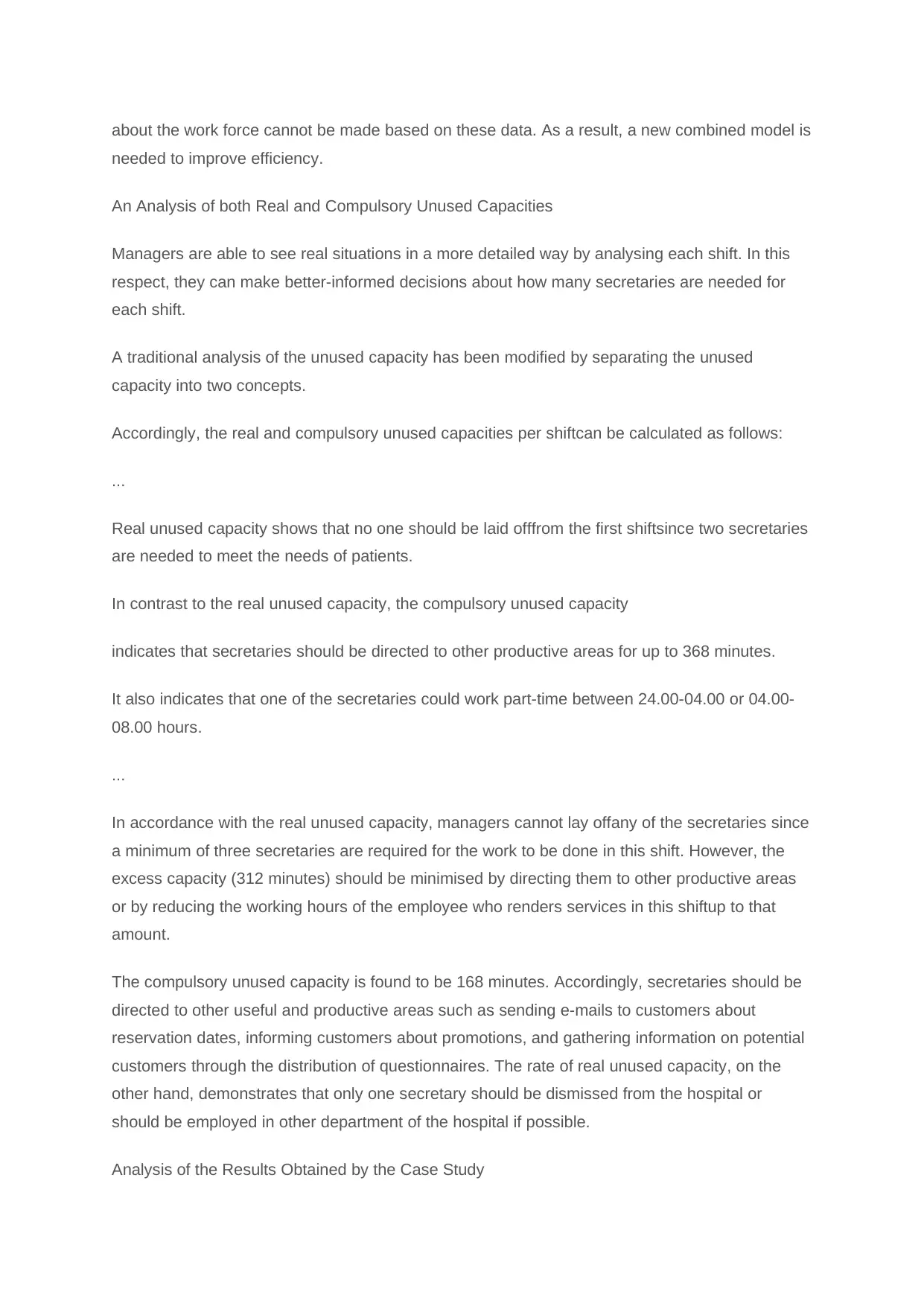

An Analysis of both Real and Compulsory Unused Capacities

Managers are able to see real situations in a more detailed way by analysing each shift. In this

respect, they can make better-informed decisions about how many secretaries are needed for

each shift.

A traditional analysis of the unused capacity has been modified by separating the unused

capacity into two concepts.

Accordingly, the real and compulsory unused capacities per shiftcan be calculated as follows:

...

Real unused capacity shows that no one should be laid offfrom the first shiftsince two secretaries

are needed to meet the needs of patients.

In contrast to the real unused capacity, the compulsory unused capacity

indicates that secretaries should be directed to other productive areas for up to 368 minutes.

It also indicates that one of the secretaries could work part-time between 24.00-04.00 or 04.00-

08.00 hours.

...

In accordance with the real unused capacity, managers cannot lay offany of the secretaries since

a minimum of three secretaries are required for the work to be done in this shift. However, the

excess capacity (312 minutes) should be minimised by directing them to other productive areas

or by reducing the working hours of the employee who renders services in this shiftup to that

amount.

The compulsory unused capacity is found to be 168 minutes. Accordingly, secretaries should be

directed to other useful and productive areas such as sending e-mails to customers about

reservation dates, informing customers about promotions, and gathering information on potential

customers through the distribution of questionnaires. The rate of real unused capacity, on the

other hand, demonstrates that only one secretary should be dismissed from the hospital or

should be employed in other department of the hospital if possible.

Analysis of the Results Obtained by the Case Study

needed to improve efficiency.

An Analysis of both Real and Compulsory Unused Capacities

Managers are able to see real situations in a more detailed way by analysing each shift. In this

respect, they can make better-informed decisions about how many secretaries are needed for

each shift.

A traditional analysis of the unused capacity has been modified by separating the unused

capacity into two concepts.

Accordingly, the real and compulsory unused capacities per shiftcan be calculated as follows:

...

Real unused capacity shows that no one should be laid offfrom the first shiftsince two secretaries

are needed to meet the needs of patients.

In contrast to the real unused capacity, the compulsory unused capacity

indicates that secretaries should be directed to other productive areas for up to 368 minutes.

It also indicates that one of the secretaries could work part-time between 24.00-04.00 or 04.00-

08.00 hours.

...

In accordance with the real unused capacity, managers cannot lay offany of the secretaries since

a minimum of three secretaries are required for the work to be done in this shift. However, the

excess capacity (312 minutes) should be minimised by directing them to other productive areas

or by reducing the working hours of the employee who renders services in this shiftup to that

amount.

The compulsory unused capacity is found to be 168 minutes. Accordingly, secretaries should be

directed to other useful and productive areas such as sending e-mails to customers about

reservation dates, informing customers about promotions, and gathering information on potential

customers through the distribution of questionnaires. The rate of real unused capacity, on the

other hand, demonstrates that only one secretary should be dismissed from the hospital or

should be employed in other department of the hospital if possible.

Analysis of the Results Obtained by the Case Study

In this case study, unused capacity was firstly analysed using the conventional method which

indicated that four employees should be dismissed from the hospital. However, how many

secretaries should be dismissed or directed to other productive areas for each shiftis not certain.

Thus, an accurate result can only be obtained by considering both the real and compulsory

unused capacities for each shift.

In order to calculate unused capacity in a business, it is first necessary to calculate practical

capacity and then compare it to the total task duration required by customers. However, this

calculation may lead to invalid results because the amount of unused capacity for each shiftmay

become less than the practical capacity of an employee, but the total amount of unused capacity

for all shifts of an activity may become higher than the practical capacity of an employee. Thus, it

may appear that:

"the total amount of unused capacity is higher than the practical capacity of an employee, so

some employees should be dismissed or employed in other departments of the hospital up to the

amount of unused capacity".

However, when the data is considered based on shifts, it becomes clear that the excessive

amount of unused capacity is a result of the summation of values found in each shift. Therefore,

the best decision is reached by analysing and considering the real and compulsory unused

capacity for each shift.

The situation discussed in the above paragraph was clarified in the service sector case study.

According to that study, a total of 848 minutes are compulsory unused capacity. An important

point here is that the compulsory unused capacity can be considered as part of the cost of having

hospitals "standing ready" to provide health care services for potential patients (Ferrier et al.,

2009). Therefore, the cost of 848 minutes (compulsory unused capacity) should be incurred.

However, so as to mitigate the effects of the compulsory unused capacity, the secretaries

working in this hospital should take on additional productive tasks for up to 848 minutes.

Meanwhile, the real unused capacities of shifts indicate that not four, but one secretary should be

dismissed from the third shiftonly, or should be employed in another department of the hospital if

possible.

Conclusion

Eliminating unused capacity is one of the main methods that companies can use to improve their

productivity. However, it is not easy to minimise or dispose of unused capacity, especially in

service companies, due to both the uncertain structure of unused capacity and the intangible

characteristics of services. Thus, in order to remove uncertainty it is necessary to consider two

new concepts.

indicated that four employees should be dismissed from the hospital. However, how many

secretaries should be dismissed or directed to other productive areas for each shiftis not certain.

Thus, an accurate result can only be obtained by considering both the real and compulsory

unused capacities for each shift.

In order to calculate unused capacity in a business, it is first necessary to calculate practical

capacity and then compare it to the total task duration required by customers. However, this

calculation may lead to invalid results because the amount of unused capacity for each shiftmay

become less than the practical capacity of an employee, but the total amount of unused capacity

for all shifts of an activity may become higher than the practical capacity of an employee. Thus, it

may appear that:

"the total amount of unused capacity is higher than the practical capacity of an employee, so

some employees should be dismissed or employed in other departments of the hospital up to the

amount of unused capacity".

However, when the data is considered based on shifts, it becomes clear that the excessive

amount of unused capacity is a result of the summation of values found in each shift. Therefore,