Visual Search and Information Processing Speed

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|46

|13333

|304

AI Summary

This chapter examines the potential impacts of nonclinical levels of anxiety, depression, subjective memory function and objective cognitive function, as well as educational level and gender, with regard to information processing speed that is related to attention in both the young and old adults through the use of commonly adopted visual search task.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

VISUAL SEARCH AND INFORMATION PROCESSING SPEED

[Author Name(s), First M. Last, Omit Titles and Degrees]

[Institutional Affiliation(s)]

[Author Name(s), First M. Last, Omit Titles and Degrees]

[Institutional Affiliation(s)]

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

CHAPTER FOUR

INFLUENCE OF SUBCLINICAL ANXIETY LEVELS ON INFORMATION

PROCESSING SPEED AND INTRA-INDIVIDUAL VARIABILITY IN YOUNGER AND

OLDER ADULTS

Introduction

The main aim of this chapter revolves around examination of the potential impacts of non-

clinical levels of anxiety, depression, subjective memory function and objective cognitive

function, as well as educational level and gender, with regard to information processing speed

that is related to attention in both the young and old adults through the use of commonly adopted

visual search task (Tales, Bayer, Haworth et al, 2010). Visual search task has found its

application on several occasions in the past in the measurement of the potential differences that

exist between information processing speed and attentional shifting using visual attention

processes that are related to information processing speed in the MCI, AD and healthy aging

(Craik, 2012).

Contrary to the way it has been done by other researchers in their previous studies (Landy et al,

2015; Kiss et al, 2012; Tales et al, 2010; Madden , Gottlob et al, 1999), the research that makes a

significant aspect of this PhD evaluates these aspects of processing of information in both the

young and older adults as well as evaluating into details the possible impacts upon such findings

of factors that are either not sufficiently addressed or completely not addressed in the previous

studies and research (Craik, 2012), (i.e. non-clinical anxiety, subjective memory function, sex

and education). This search topic also aims at finding out how the factor that might have been

INFLUENCE OF SUBCLINICAL ANXIETY LEVELS ON INFORMATION

PROCESSING SPEED AND INTRA-INDIVIDUAL VARIABILITY IN YOUNGER AND

OLDER ADULTS

Introduction

The main aim of this chapter revolves around examination of the potential impacts of non-

clinical levels of anxiety, depression, subjective memory function and objective cognitive

function, as well as educational level and gender, with regard to information processing speed

that is related to attention in both the young and old adults through the use of commonly adopted

visual search task (Tales, Bayer, Haworth et al, 2010). Visual search task has found its

application on several occasions in the past in the measurement of the potential differences that

exist between information processing speed and attentional shifting using visual attention

processes that are related to information processing speed in the MCI, AD and healthy aging

(Craik, 2012).

Contrary to the way it has been done by other researchers in their previous studies (Landy et al,

2015; Kiss et al, 2012; Tales et al, 2010; Madden , Gottlob et al, 1999), the research that makes a

significant aspect of this PhD evaluates these aspects of processing of information in both the

young and older adults as well as evaluating into details the possible impacts upon such findings

of factors that are either not sufficiently addressed or completely not addressed in the previous

studies and research (Craik, 2012), (i.e. non-clinical anxiety, subjective memory function, sex

and education). This search topic also aims at finding out how the factor that might have been

ignored in the previous studies could affect the speed of processing information and their

influence on the future. An interpretation of the visual search test results are interpreted with

focus given to that which encompasses an ostensibly cognitively health older adult control group

while performing studies on function that are related to visual attention and the speed if

processing information in dementia and MCI.

Cognitive aging is typically defined on the basis of a general decrease in the levels of cognitive

performance especially a general decline in the processing speed based on the mean performance

of an individual (Kapur, 2015). In the most recent past, it has been noticed that there is a rise in

intra-individual variability (IIV), with an increase in age categorically in older adults Bunce, D.

et al. (2013). The neuroimaging research that has been going on about aging has conventionally

given a lot of attention on the trends of the mean groups including mean cognitive decline with

age. To date, there are still very few studies that exist as afar as variability is concerned. This

leads to very little knowledge available regarding neural underpinnings of RT and IIV. As

mentioned in the previous chapters, the current study is focused on establishing and examining

the age differences in information processing speed and its variability in relationship with non-

clinical anxiety levels (in particular), subjective memory function, objective cognitive function

and other related factors such as sex and years of education as well as depression that have not

investigated before, by using the visual search take.

Numerous approaches are used in the description of the variability of the behavior of an

individual. These ways of behavioral individual variability can be summed up into four: Short-

term, also called trail to trail within the variability of the task or inconsistency Luck, S. J., &

Vogel, E. K. (2013) - This way illustrates the rapid and transient fluctuations that take place over

short scales of time for example within a task that os performed in barely 10 minutes.

influence on the future. An interpretation of the visual search test results are interpreted with

focus given to that which encompasses an ostensibly cognitively health older adult control group

while performing studies on function that are related to visual attention and the speed if

processing information in dementia and MCI.

Cognitive aging is typically defined on the basis of a general decrease in the levels of cognitive

performance especially a general decline in the processing speed based on the mean performance

of an individual (Kapur, 2015). In the most recent past, it has been noticed that there is a rise in

intra-individual variability (IIV), with an increase in age categorically in older adults Bunce, D.

et al. (2013). The neuroimaging research that has been going on about aging has conventionally

given a lot of attention on the trends of the mean groups including mean cognitive decline with

age. To date, there are still very few studies that exist as afar as variability is concerned. This

leads to very little knowledge available regarding neural underpinnings of RT and IIV. As

mentioned in the previous chapters, the current study is focused on establishing and examining

the age differences in information processing speed and its variability in relationship with non-

clinical anxiety levels (in particular), subjective memory function, objective cognitive function

and other related factors such as sex and years of education as well as depression that have not

investigated before, by using the visual search take.

Numerous approaches are used in the description of the variability of the behavior of an

individual. These ways of behavioral individual variability can be summed up into four: Short-

term, also called trail to trail within the variability of the task or inconsistency Luck, S. J., &

Vogel, E. K. (2013) - This way illustrates the rapid and transient fluctuations that take place over

short scales of time for example within a task that os performed in barely 10 minutes.

Intraindividual variability throughout tasks, also called dispersion. Alterations that are relatively

permanent and gradually evolve over comparatively long time scales for example over months or

year through developments or training- This way of behavioral individual change is defined as

intraindividual change. Intraindividual variability or a variability between individual and is also

defined as diversity (Schmorrow, 2009). These changes are of essence to the study as they can be

used as predicate of the personal traits of an individual and this can be used as the basis for

grouping of people into either healthy or people with cognitive memory impairment.

A study, cognitive intraindividual variability and white matter integrity in aging (Smith, 2014),

was done that focused on inconsistency that is also defined as variability within a short task or

short term. In the paper, inconsistency was referred to as IIV. Cognitive intraindividual

variability and white matter integrity in aging studies have noticed that inconsistency tends to

increase with an increasing in age as individual approaches adulthood (Smith, 2014). Such

studies are also supportive of the fact inconsistency is a stable and meaningful illustrator of the

difference between individuals. Most cognitive intraindividual variability and white matter

integrity in aging studies have adopted and used the paradigms of reaction time (RT) and have

noticed that as the age increases, there is a significant increase in the individual standard

deviations. This is so even after controlling has been done for the response time base rate.

The findings painted a less clear picture with reference to the accuracy based scores. This is due

to the fact that there are just but a few studies on the one hand and the failure of numerous

authors to notice an increase in IIV with age through the utilization of the accuracy scores on the

other hand. Other studies have also demonstrated a U-shaper curve that occurs across the

lifespan in relation to IIV as young and older adults illustrate a large inconsistency levels. In

addition, in as much as inconsistency is often associated with possibility of dysfunction, it is

permanent and gradually evolve over comparatively long time scales for example over months or

year through developments or training- This way of behavioral individual change is defined as

intraindividual change. Intraindividual variability or a variability between individual and is also

defined as diversity (Schmorrow, 2009). These changes are of essence to the study as they can be

used as predicate of the personal traits of an individual and this can be used as the basis for

grouping of people into either healthy or people with cognitive memory impairment.

A study, cognitive intraindividual variability and white matter integrity in aging (Smith, 2014),

was done that focused on inconsistency that is also defined as variability within a short task or

short term. In the paper, inconsistency was referred to as IIV. Cognitive intraindividual

variability and white matter integrity in aging studies have noticed that inconsistency tends to

increase with an increasing in age as individual approaches adulthood (Smith, 2014). Such

studies are also supportive of the fact inconsistency is a stable and meaningful illustrator of the

difference between individuals. Most cognitive intraindividual variability and white matter

integrity in aging studies have adopted and used the paradigms of reaction time (RT) and have

noticed that as the age increases, there is a significant increase in the individual standard

deviations. This is so even after controlling has been done for the response time base rate.

The findings painted a less clear picture with reference to the accuracy based scores. This is due

to the fact that there are just but a few studies on the one hand and the failure of numerous

authors to notice an increase in IIV with age through the utilization of the accuracy scores on the

other hand. Other studies have also demonstrated a U-shaper curve that occurs across the

lifespan in relation to IIV as young and older adults illustrate a large inconsistency levels. In

addition, in as much as inconsistency is often associated with possibility of dysfunction, it is

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

arguable that it is one of the pieces of evidence of an adaptive dynamic process (Gonçalves-

Pereira, 2016).

Despite the tremendous growth in studies have been witnessed over the past, not so much

knowledge on information processing speed and inconsistency in aging are available as well as

there is very little research to show on its neural underpinning. As Hultsch et al. once mentioned,

in relation to the corpus work which is based on the mean performance level, the quantity and

quality of information that has been brought forth by research imaging and cognition is

miniscule. More specifically, it is not any clear whether or not there are the same bases for mean

performance and IIV. Hultsch et al. observes that despite the available information still in very

rare unity, the available research findings have been able to illustrate a link between IIV and the

characteristics of the human brain through the use of either functional or structural brining

imaging (Q. Ashton Acton, 2012).

Bunce and colleagues were able to illustrate that there was an association between the hyper

intensities of the white matter in the frontal cortex and the larger IIV within a response time task.

Their finding was not with performance tasks that are perceived to be more complex (Craik,

2012). Other findings reported that there is a correlation between the volume of white matter and

IIV in response time, RTs. The very findings also established that response times are more

correlated with the volume of the cortical grey matter, GM. Through a comparison that was

made between the influence of white matter and grey matter on IIV in both the young and old

adults, the scholar found out that only the white matter had an influence and impact on the

increase of behavioral inconsistences that is related to age. Of all the parameters of DTI, it was

found out that only fractional anisotropy, FA was linked to the cognitive variability upon the

control of age as a factor Zhang, R et al. (2018).

Pereira, 2016).

Despite the tremendous growth in studies have been witnessed over the past, not so much

knowledge on information processing speed and inconsistency in aging are available as well as

there is very little research to show on its neural underpinning. As Hultsch et al. once mentioned,

in relation to the corpus work which is based on the mean performance level, the quantity and

quality of information that has been brought forth by research imaging and cognition is

miniscule. More specifically, it is not any clear whether or not there are the same bases for mean

performance and IIV. Hultsch et al. observes that despite the available information still in very

rare unity, the available research findings have been able to illustrate a link between IIV and the

characteristics of the human brain through the use of either functional or structural brining

imaging (Q. Ashton Acton, 2012).

Bunce and colleagues were able to illustrate that there was an association between the hyper

intensities of the white matter in the frontal cortex and the larger IIV within a response time task.

Their finding was not with performance tasks that are perceived to be more complex (Craik,

2012). Other findings reported that there is a correlation between the volume of white matter and

IIV in response time, RTs. The very findings also established that response times are more

correlated with the volume of the cortical grey matter, GM. Through a comparison that was

made between the influence of white matter and grey matter on IIV in both the young and old

adults, the scholar found out that only the white matter had an influence and impact on the

increase of behavioral inconsistences that is related to age. Of all the parameters of DTI, it was

found out that only fractional anisotropy, FA was linked to the cognitive variability upon the

control of age as a factor Zhang, R et al. (2018).

On the contrary, a control for the mean performance as was observed by another research

established significant relationship and correlations between all the parameters of DTI and the

inconsistency in a great sample of healthy individuals. Suggestions were also made that cognitive

variability which is having a higher correlation with these parameters than the median

performance would prove to be a better correlate o the variations in the structure of the white

matter; as the strength of such correlations were observed to increase in the older adults

(Goswami, 2015).

Theoretical and practical link between delay in cognition and the pace of information processing

is a measurement that is commonly applied in the research process as an indicator of human

behavior. Studies provide considerable evidences in support of inter-relationship between

cognition, information processing speed, behavior and white and grey matter integrity adopted

through aging (Akimoto et al., 2014). Slowing of information processing speeds as one grows

older is connected to structural changes, which conceptually affect the general brain functions,

perceptions of functional integrity and cognition gradually (Akimoto et al., 2014). Younger

adults are generally exceptionally active in comparison with older adults, as their general brain

functioning is still active and observing normal performance in structural aspects (Bryant et al.,

2008). In other words, probabilities of MCI, Alzheimer and slow information processing speed

are far less in young individuals, in comparison with their older counterparts (Tales et al., 2010).

Based on that, RT measures need to consider many aspects of typical behavior and

environmental interaction (Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Results of

information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted with respect

to such caveats, making it difficult to relate clinical findings to research findings. It is included in

DSM-5 for measurement, specifically with respect to attention-related processing (Naveteur

established significant relationship and correlations between all the parameters of DTI and the

inconsistency in a great sample of healthy individuals. Suggestions were also made that cognitive

variability which is having a higher correlation with these parameters than the median

performance would prove to be a better correlate o the variations in the structure of the white

matter; as the strength of such correlations were observed to increase in the older adults

(Goswami, 2015).

Theoretical and practical link between delay in cognition and the pace of information processing

is a measurement that is commonly applied in the research process as an indicator of human

behavior. Studies provide considerable evidences in support of inter-relationship between

cognition, information processing speed, behavior and white and grey matter integrity adopted

through aging (Akimoto et al., 2014). Slowing of information processing speeds as one grows

older is connected to structural changes, which conceptually affect the general brain functions,

perceptions of functional integrity and cognition gradually (Akimoto et al., 2014). Younger

adults are generally exceptionally active in comparison with older adults, as their general brain

functioning is still active and observing normal performance in structural aspects (Bryant et al.,

2008). In other words, probabilities of MCI, Alzheimer and slow information processing speed

are far less in young individuals, in comparison with their older counterparts (Tales et al., 2010).

Based on that, RT measures need to consider many aspects of typical behavior and

environmental interaction (Rodrigues & Pandeirada, 2014; Tales & Basoudan, 2016). Results of

information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted with respect

to such caveats, making it difficult to relate clinical findings to research findings. It is included in

DSM-5 for measurement, specifically with respect to attention-related processing (Naveteur

et.al. 2005). Research indicates that information processing speed can vary significantly with

respect to methodological factors such as the task used and thus areas of the brain recruited for

performance and response demands and person-related factors such as sex and educational level

(Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Such research evidence indicates that the results of

information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted with respect

to such caveats, especially as there is a high degree of variability in the tasks used to measure

information processing speeds in clinical populations, making the comparison of results within

the clinical arena problematic and also making it difficult to relate clinical findings to research

findings. Information processing speed that is related to ageing has either failed to successfully

address sex as one of the factors influencing the relation or made a concrete comparison between

the impacts of sex on the speed of information processing same as with the case of years of

educatio (John, 2012)n. Furthermore, DSM 5 that elaborates on the need of measuring the speed

of information processing does not provide any elaborations on the impacts of sex and years of

education and the possible effects on the results generated by RT studies.

It is possible that other factors that are rarely researched and rarely tested in clinical conditions,

may also affect information processing speed. One such factor is anxiety. Salthouse (2011)

highlighted the possibility that anxiety may affect RT performance and that although high levels

of clinical anxiety may be acknowledged to affect information processing speeds, lower levels of

anxiety are generally not considered to have any effect. In contrast, however, Tales and

Basoudan (2016) noted that anxiety has a high prevalence in older adults and that even non-

clinical anxiety may impact cognitive performance. One aim of this research is to determine the

potential of sub-clinical anxiety to affect the outcome of information processing speed in older

adults, as well as in younger adults.

respect to methodological factors such as the task used and thus areas of the brain recruited for

performance and response demands and person-related factors such as sex and educational level

(Tales, Bayer, Haworth & Snowden, 2010). Such research evidence indicates that the results of

information processing speed tests in clinical populations may need to be interpreted with respect

to such caveats, especially as there is a high degree of variability in the tasks used to measure

information processing speeds in clinical populations, making the comparison of results within

the clinical arena problematic and also making it difficult to relate clinical findings to research

findings. Information processing speed that is related to ageing has either failed to successfully

address sex as one of the factors influencing the relation or made a concrete comparison between

the impacts of sex on the speed of information processing same as with the case of years of

educatio (John, 2012)n. Furthermore, DSM 5 that elaborates on the need of measuring the speed

of information processing does not provide any elaborations on the impacts of sex and years of

education and the possible effects on the results generated by RT studies.

It is possible that other factors that are rarely researched and rarely tested in clinical conditions,

may also affect information processing speed. One such factor is anxiety. Salthouse (2011)

highlighted the possibility that anxiety may affect RT performance and that although high levels

of clinical anxiety may be acknowledged to affect information processing speeds, lower levels of

anxiety are generally not considered to have any effect. In contrast, however, Tales and

Basoudan (2016) noted that anxiety has a high prevalence in older adults and that even non-

clinical anxiety may impact cognitive performance. One aim of this research is to determine the

potential of sub-clinical anxiety to affect the outcome of information processing speed in older

adults, as well as in younger adults.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Another factor that has rarely been considered in the investigation of information processing

speed in ageing and ageing-related disease is subjective cognitive function. There has been

growing concerns about cognitive decline specifically in memory mostly in older adults and it is

increasing becoming evident that both dementia and MCI could be characterized by an earlier

stage which is normally termed as subjective cognitive impairment. It should be noted however

that complaints of subjective cognitive are not always representative of a prodromal stage of

dementia with some of the causes such as sleep disorder, anxiety and anxiety being potentially

responsive. Regardless of the casualty there have been concerns on the negative impacts that

memory function can have on the everyday life as well as the mental health Donaghy, P. C.,

O'brien, J. T., & Thomas, A. J. (2015).

SCI are associated with neuropsychological test performance that is objectively defined (John,

2012). Chances are that objective change can be missing in functions including memory since

the test adopted are at times insensitive and hence cannot be used in ,measuring the specific

aspects of the memory of an individual. there can be detrimental changes that can occur in the

functions of the brain other than the fact that memory may take place in what is referred to SCI

even though this may be challenging to be described by the general public (Goswami, 2015).

Available evidence illustrates that there is significant disruption of the operations of the

fundamental brain in people with SCI. this makes it a possibility that the fundamental process of

the brain may lead to impairment of the function of the memory even though there has not been

any concrete evidence from the existing neuropsychological protocol of testing.

In as much as there is proof of existence of a relation between cognition, information processing

speed, integrity of white and grey matter and behavior especially in aging, dementia and MCI,

speed in ageing and ageing-related disease is subjective cognitive function. There has been

growing concerns about cognitive decline specifically in memory mostly in older adults and it is

increasing becoming evident that both dementia and MCI could be characterized by an earlier

stage which is normally termed as subjective cognitive impairment. It should be noted however

that complaints of subjective cognitive are not always representative of a prodromal stage of

dementia with some of the causes such as sleep disorder, anxiety and anxiety being potentially

responsive. Regardless of the casualty there have been concerns on the negative impacts that

memory function can have on the everyday life as well as the mental health Donaghy, P. C.,

O'brien, J. T., & Thomas, A. J. (2015).

SCI are associated with neuropsychological test performance that is objectively defined (John,

2012). Chances are that objective change can be missing in functions including memory since

the test adopted are at times insensitive and hence cannot be used in ,measuring the specific

aspects of the memory of an individual. there can be detrimental changes that can occur in the

functions of the brain other than the fact that memory may take place in what is referred to SCI

even though this may be challenging to be described by the general public (Goswami, 2015).

Available evidence illustrates that there is significant disruption of the operations of the

fundamental brain in people with SCI. this makes it a possibility that the fundamental process of

the brain may lead to impairment of the function of the memory even though there has not been

any concrete evidence from the existing neuropsychological protocol of testing.

In as much as there is proof of existence of a relation between cognition, information processing

speed, integrity of white and grey matter and behavior especially in aging, dementia and MCI,

not so much information is available on the relation between information speed process and SCI

especially in individuals who undergo subjective changes in the functioning of the memory when

there is no clinical investigation (Smith, 2014). Chances are that a slowing rate in the speed of

information processing in the memory could indicate changes in the structure for example in the

while matter which the routine neuropsychological tests are not sensitive to, but has effects on

the general functioning of the brain, the perception of the integrity of function and cognition.

Structural normality could be assumed in cases where individuals that have impaired memory

preserve the processing speed of information.

A study on the perception and reality on cognitive was hence conducted that investigated the

perceived memory function with regard to the information processing speed in older adults

having normal levels of general cognitive function and no significant levels if anxiety. Besides,

metacognition could be considered as one of the factors of self-perception of the majority

integrity and cognition (Gonçalves-Pereira, 2016). The study also aimed at establishing if there is

relation between the performance of the memory and perception of task difficulty and whether or

not the perceived difference in task has a relation with the actual speed of processing

information.

Evidence is available that is supportive of the fact that the information processing speed can have

a significant difference in relation to the test that is adopted due to the various brain networks

and processes that are being adopted. The findings of the study was done using the one varied

measure, computer administered visual search.

A comparison of the inftomation processing speed has illustrated to be slower MCI and AD than

in healthy ageing. The Haworth et al, 2016; Tales et al, 2010; McLaughlin et al, 2010; Tales et

especially in individuals who undergo subjective changes in the functioning of the memory when

there is no clinical investigation (Smith, 2014). Chances are that a slowing rate in the speed of

information processing in the memory could indicate changes in the structure for example in the

while matter which the routine neuropsychological tests are not sensitive to, but has effects on

the general functioning of the brain, the perception of the integrity of function and cognition.

Structural normality could be assumed in cases where individuals that have impaired memory

preserve the processing speed of information.

A study on the perception and reality on cognitive was hence conducted that investigated the

perceived memory function with regard to the information processing speed in older adults

having normal levels of general cognitive function and no significant levels if anxiety. Besides,

metacognition could be considered as one of the factors of self-perception of the majority

integrity and cognition (Gonçalves-Pereira, 2016). The study also aimed at establishing if there is

relation between the performance of the memory and perception of task difficulty and whether or

not the perceived difference in task has a relation with the actual speed of processing

information.

Evidence is available that is supportive of the fact that the information processing speed can have

a significant difference in relation to the test that is adopted due to the various brain networks

and processes that are being adopted. The findings of the study was done using the one varied

measure, computer administered visual search.

A comparison of the inftomation processing speed has illustrated to be slower MCI and AD than

in healthy ageing. The Haworth et al, 2016; Tales et al, 2010; McLaughlin et al, 2010; Tales et

al, 2005; Greenwood et al, 1997 studies, which made the comparison established through

comparing MCI or AD with older adults who were ostensibly healthy that the levels of

information processing is normal in the healthy ageing adults. The objective cognitive function

of a control group in normally tested and considered in most studies such that an individual that

has a very low score of subjective cognitive function is not allowed from being part of the

control group. This is despite the fact that a few individuals who are members of the control

group may demonstrate problems related to tier cognition that is associated with disproportionate

growing, one of the types of slowing that is evident and common among the abnormal ageing.

This study gave focus to functioning of the subjective memory in which the older adults have an

idea of changes in their memory function even though they have not paid a visit to their GP and

hence not yet diagnosed with SCI (Tabor, 2009). The older adults who have been picked from

the local community, in a research control, may be victims of not yet detected subjective

memory function which may also be illustrative of abnormal ageing and hence disqualifying

such a group of people from being included in the groups of healthy adults.

A research, Reed, 2010; Cook & Marsiske, 2005; Earles & Salthouse, 1995; Schofield, Marder,

Dooneief et al., 1997, was conducted and established an asscoaition between subjective

complaints and baseline cognitive impairment diagnosis. This research, however only relates to

SCI and so far there have not been conducted any studies on the ageing using visul search in the

evaluation of the subjective memory function in association with information processing speed

and IIV in a community comprising of older adults. The initial study thus examined the

possibility of characterizing subjective memory function by increased IIV and slow RT hence a

factor in SCI characterization

comparing MCI or AD with older adults who were ostensibly healthy that the levels of

information processing is normal in the healthy ageing adults. The objective cognitive function

of a control group in normally tested and considered in most studies such that an individual that

has a very low score of subjective cognitive function is not allowed from being part of the

control group. This is despite the fact that a few individuals who are members of the control

group may demonstrate problems related to tier cognition that is associated with disproportionate

growing, one of the types of slowing that is evident and common among the abnormal ageing.

This study gave focus to functioning of the subjective memory in which the older adults have an

idea of changes in their memory function even though they have not paid a visit to their GP and

hence not yet diagnosed with SCI (Tabor, 2009). The older adults who have been picked from

the local community, in a research control, may be victims of not yet detected subjective

memory function which may also be illustrative of abnormal ageing and hence disqualifying

such a group of people from being included in the groups of healthy adults.

A research, Reed, 2010; Cook & Marsiske, 2005; Earles & Salthouse, 1995; Schofield, Marder,

Dooneief et al., 1997, was conducted and established an asscoaition between subjective

complaints and baseline cognitive impairment diagnosis. This research, however only relates to

SCI and so far there have not been conducted any studies on the ageing using visul search in the

evaluation of the subjective memory function in association with information processing speed

and IIV in a community comprising of older adults. The initial study thus examined the

possibility of characterizing subjective memory function by increased IIV and slow RT hence a

factor in SCI characterization

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

It is possible that subjectively poor cognition, by itself and in combination with anxiety, may

also affect information processing speed (either through similar or different mechanisms, yet to

be fully identified. If this is the case, then both clinical and research findings would need to be

interpreted with respect to this caveat also.

The Visual Search Task

Visual search has direct relationship with selective processing information and selective

attention. It refers to the application of vision to search different objects and articles

(Commodari, & Guarnera, 2013). The Single Detection Theory demonstrates how visual

attention has its impact and influence on tasks involving search of the targeted objects among

distractors. The studies conducted on the topics of physiology and psycho-physics reveal that

performance in a search task is largely determined by the discriminability of the target from the

distractors. Hence, the object being searched contains unique or dissimilar characteristics,

including size, colour, mass and shape, an image of which has developed in brain, and helps the

individuals in searching and finding the required object among the distractors, while seeking

support from selectively processed information. Hence, attention plays a dominant role by

increasing the response to the attended stimulus, by confining the search to the specific traits of

the object under-consideration among distractors. Consequently, both these processes improve

the search performance by increasing the discriminability of the attended signal (Verghese,

2008).

The significance of visual search can be understood by its application as a common tool for

identification as objects by individuals, and for studying the topics related to cognition ranging,

decision-making, oculomotor control to memory, rewards and active vision on the part of the

humans (Eckstein, 2011). Generally, visual search looks to be a simple and easy task for the

also affect information processing speed (either through similar or different mechanisms, yet to

be fully identified. If this is the case, then both clinical and research findings would need to be

interpreted with respect to this caveat also.

The Visual Search Task

Visual search has direct relationship with selective processing information and selective

attention. It refers to the application of vision to search different objects and articles

(Commodari, & Guarnera, 2013). The Single Detection Theory demonstrates how visual

attention has its impact and influence on tasks involving search of the targeted objects among

distractors. The studies conducted on the topics of physiology and psycho-physics reveal that

performance in a search task is largely determined by the discriminability of the target from the

distractors. Hence, the object being searched contains unique or dissimilar characteristics,

including size, colour, mass and shape, an image of which has developed in brain, and helps the

individuals in searching and finding the required object among the distractors, while seeking

support from selectively processed information. Hence, attention plays a dominant role by

increasing the response to the attended stimulus, by confining the search to the specific traits of

the object under-consideration among distractors. Consequently, both these processes improve

the search performance by increasing the discriminability of the attended signal (Verghese,

2008).

The significance of visual search can be understood by its application as a common tool for

identification as objects by individuals, and for studying the topics related to cognition ranging,

decision-making, oculomotor control to memory, rewards and active vision on the part of the

humans (Eckstein, 2011). Generally, visual search looks to be a simple and easy task for the

individuals; consequently, computer engineers and scientists appear to be interested in recreating

human visual search abilities in computer machines for the benefit of the individuals (Eckstein,

2011). Searching different objects for using them to accomplish the tasks serves as a routine

matter for the individuals, and the brain helps them by guiding them to visualize the articles of

various types to select and pick them with the help of vision (Eckstein, 2011).

However, various factors may negatively influence the visual search process by affecting the

memory and causing distractions for the individuals. Clinical Anxiety levels, depression,

sleeplessness, life style and aging can be named as some of the most important factors behind the

weakening of visual search in people (Commodari, & Guarnera, 2013). Effects on information

processing speed can also be a powerful reason behind poor visual search. Since information

processing speed helps the individual in the flow of information and commands from brain to

other body organs, the effect of non-clinical anxiety on it slows down the performance of the

brain and body subsequently. One of the most exciting reasons behind the exploration of the

causes of anxiety includes the assessment of its impact on slowing the information processing

speed, which impacts the execution of visual search tasks, as well as performing different tasks

in a normal and appropriate way which is the main investigation of the current study.

Visual search is a type of task of perceptional demanding attention which specifically involves

actively scanning the visual environment for a specific feature or object which is the target

among other objects or features. Visual search occurs without the eyes moving and the capability

to locate target features or objects consciously among a sophisticated array of stimuli have

undergone elaborate studies for numerous decades in the past (Yudofsky, 2011). There are

numerous practical applications of visual task that can be experienced in the normal daily life for

example when an individual is picking out a commodity on the shelf of a supermarket, when

human visual search abilities in computer machines for the benefit of the individuals (Eckstein,

2011). Searching different objects for using them to accomplish the tasks serves as a routine

matter for the individuals, and the brain helps them by guiding them to visualize the articles of

various types to select and pick them with the help of vision (Eckstein, 2011).

However, various factors may negatively influence the visual search process by affecting the

memory and causing distractions for the individuals. Clinical Anxiety levels, depression,

sleeplessness, life style and aging can be named as some of the most important factors behind the

weakening of visual search in people (Commodari, & Guarnera, 2013). Effects on information

processing speed can also be a powerful reason behind poor visual search. Since information

processing speed helps the individual in the flow of information and commands from brain to

other body organs, the effect of non-clinical anxiety on it slows down the performance of the

brain and body subsequently. One of the most exciting reasons behind the exploration of the

causes of anxiety includes the assessment of its impact on slowing the information processing

speed, which impacts the execution of visual search tasks, as well as performing different tasks

in a normal and appropriate way which is the main investigation of the current study.

Visual search is a type of task of perceptional demanding attention which specifically involves

actively scanning the visual environment for a specific feature or object which is the target

among other objects or features. Visual search occurs without the eyes moving and the capability

to locate target features or objects consciously among a sophisticated array of stimuli have

undergone elaborate studies for numerous decades in the past (Yudofsky, 2011). There are

numerous practical applications of visual task that can be experienced in the normal daily life for

example when an individual is picking out a commodity on the shelf of a supermarket, when

attempting to locate a friend in a multitude of people, when animals are trying to find food

among piles of leaves or even when an individual is playing the visual search games.

The level of attention in most of the visual search paradigms is determined by the movement of

the eyes despite suggestions for elaborate research that the movement of the eye is independent

of the attention and hence not an accurate and a reliable method in the evaluation of the function

of attention. In most cases, the previous studies have adopted reaction time in the measurement

of the time taken to detect the target feature or object among the various detractors it is inside.

An illustration of such may be a green square which is the target being located amongst a group

of red circles which in this case serve as the distractors.

There are two types of search: feature search and conjunction search. Feature search is also

called effacement or disjunctive search. In feature search type of visual search, the main focus is

identification of a target that was requested previously among the distractors which are different

from the target through a unique and specific feature. The unique feature may be the shape, size,

color or the orientation (Spielberger, 2013). An illustration of such may be a green square which

is the target being located amongst a group of red circles which in this case serve as the

distractors. In feature search, the distractors have the same visual features which make them

distinct from the target features or objects.

The pop out effect is influential in the determination of the efficiency of the feature search in

relation to reaction time. The op out effect is an aspect of the feature search that gives the target

the characteristic ability of being unique and conspicuous out of the surrounding distractors

following its unique features. The utilization of the detectors of feature in the processing f the

characteristics of the stimuli and separating a target from the distractors is explored using the

among piles of leaves or even when an individual is playing the visual search games.

The level of attention in most of the visual search paradigms is determined by the movement of

the eyes despite suggestions for elaborate research that the movement of the eye is independent

of the attention and hence not an accurate and a reliable method in the evaluation of the function

of attention. In most cases, the previous studies have adopted reaction time in the measurement

of the time taken to detect the target feature or object among the various detractors it is inside.

An illustration of such may be a green square which is the target being located amongst a group

of red circles which in this case serve as the distractors.

There are two types of search: feature search and conjunction search. Feature search is also

called effacement or disjunctive search. In feature search type of visual search, the main focus is

identification of a target that was requested previously among the distractors which are different

from the target through a unique and specific feature. The unique feature may be the shape, size,

color or the orientation (Spielberger, 2013). An illustration of such may be a green square which

is the target being located amongst a group of red circles which in this case serve as the

distractors. In feature search, the distractors have the same visual features which make them

distinct from the target features or objects.

The pop out effect is influential in the determination of the efficiency of the feature search in

relation to reaction time. The op out effect is an aspect of the feature search that gives the target

the characteristic ability of being unique and conspicuous out of the surrounding distractors

following its unique features. The utilization of the detectors of feature in the processing f the

characteristics of the stimuli and separating a target from the distractors is explored using the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

bottom-up processing which basically refers to the information processing which relies on the

input from the surrounding. There is still the concept of parallel processing which is the strategy

that permits the detectors of one’s feature to work at the same time in the identification of a

target.

Conjunction search is also called serial or inefficient search and refers to a visual process whose

focus is on the identification of a target that had been requested previously and is surrounded by

distractors which have a feature or more that is common to the visual features of the very target.

An example that can be used in the illustration of a conjunction search is a situation where an

individual is identifying a red X which is the target among distractors that are made up of black

Xs of the same shape and red Os that have the same color as the target. Contrary to feature

search, conjunction search incorporates distractors that may be different from each other but

have at least a common characteristic with the target (Schmorrow, 2009). The quantity of

distractors as well as the distractor ratio is some of the core elements that determine the

efficiency of conjunction search in relation to reaction time and the accuracy.

Since the distractors demonstrate that the individual features are more equal among themselves,

there is an increase in the reaction time and a corresponding decrease in the accuracy. With an

increase in the number of distractors, there is an increase in the reaction time and a

corresponding decrease in the accuracy even though there is a tendency of improvement

whenever there is practice of the restraints of the original reaction time of conjunction search.

Conjunction search makes use of bottom-up processes at the initial stages of processing in the

identification of the pre-specified feature that are evident among the stimuli. These early stages

of processes are overtaken by a more serial process that is used in the conscious evaluation of the

identified features of the stimuli so as to allow proper allocation of the focal spatial attention of

input from the surrounding. There is still the concept of parallel processing which is the strategy

that permits the detectors of one’s feature to work at the same time in the identification of a

target.

Conjunction search is also called serial or inefficient search and refers to a visual process whose

focus is on the identification of a target that had been requested previously and is surrounded by

distractors which have a feature or more that is common to the visual features of the very target.

An example that can be used in the illustration of a conjunction search is a situation where an

individual is identifying a red X which is the target among distractors that are made up of black

Xs of the same shape and red Os that have the same color as the target. Contrary to feature

search, conjunction search incorporates distractors that may be different from each other but

have at least a common characteristic with the target (Schmorrow, 2009). The quantity of

distractors as well as the distractor ratio is some of the core elements that determine the

efficiency of conjunction search in relation to reaction time and the accuracy.

Since the distractors demonstrate that the individual features are more equal among themselves,

there is an increase in the reaction time and a corresponding decrease in the accuracy. With an

increase in the number of distractors, there is an increase in the reaction time and a

corresponding decrease in the accuracy even though there is a tendency of improvement

whenever there is practice of the restraints of the original reaction time of conjunction search.

Conjunction search makes use of bottom-up processes at the initial stages of processing in the

identification of the pre-specified feature that are evident among the stimuli. These early stages

of processes are overtaken by a more serial process that is used in the conscious evaluation of the

identified features of the stimuli so as to allow proper allocation of the focal spatial attention of

an individual towards the stimulus that has the highest correlation with the target (Rahman,

2013).

In most cases, top-down processing influences conjunction search through the removal of the

stimuli that are not congruent with the previous knowledge of an individual of the description of

the target which finally allows for higher efficiency in the identification of the target. An

illustration of the influence of top-down processes on a conjunction search task is the search for a

red K among black Ks and red Cs in which the individual would ignore the black letter and shift

focus on the remaining red letter so as to reduce the set of possible targets and thus identification

of the target in a more efficient way.

Biological basis for feature and conjunction search

There has been elicited much aviation by the posterior parietal cortex in search experiments

during functional magnetic response (fMRI) as well as electroencephalography (EEG)

experiments for the cases of inefficient conjunction search, a situation that has been confirmed

by lesion studies. There have been recorded low accuracy as well as very low times of reaction

among patients who have lesions to the posterior parietal cortex during conjunction search even

though they have intact feature search that remains in the ipsilesional side of the space. Walsh,

Ashbridge and Cowey (1997), in the study demonstrated that there was impairment of

conjunction such by about 100 milliseconds after the onset of the stimuli during the application

of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) on to the right parietal cortex. In yet another study,

Nobre, Coull, Walsh and Frith (2003), used functional magnetic resonance imaging in the

identification that there is identification of the intraparietal sulcus that are located in the superior

parietal cortex to specifically feature search as well as the binding of the individual features of

2013).

In most cases, top-down processing influences conjunction search through the removal of the

stimuli that are not congruent with the previous knowledge of an individual of the description of

the target which finally allows for higher efficiency in the identification of the target. An

illustration of the influence of top-down processes on a conjunction search task is the search for a

red K among black Ks and red Cs in which the individual would ignore the black letter and shift

focus on the remaining red letter so as to reduce the set of possible targets and thus identification

of the target in a more efficient way.

Biological basis for feature and conjunction search

There has been elicited much aviation by the posterior parietal cortex in search experiments

during functional magnetic response (fMRI) as well as electroencephalography (EEG)

experiments for the cases of inefficient conjunction search, a situation that has been confirmed

by lesion studies. There have been recorded low accuracy as well as very low times of reaction

among patients who have lesions to the posterior parietal cortex during conjunction search even

though they have intact feature search that remains in the ipsilesional side of the space. Walsh,

Ashbridge and Cowey (1997), in the study demonstrated that there was impairment of

conjunction such by about 100 milliseconds after the onset of the stimuli during the application

of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) on to the right parietal cortex. In yet another study,

Nobre, Coull, Walsh and Frith (2003), used functional magnetic resonance imaging in the

identification that there is identification of the intraparietal sulcus that are located in the superior

parietal cortex to specifically feature search as well as the binding of the individual features of

perception in contrary to conjunction search. The authors further identified that bilateral eliciting

occurs during fMRI experiments in the superior parietal lobe alongside the right angular gyrus in

for the conjunction search.

On the contrary, Leonards, Sunaert, Vam Hecke and Orban (2000) came up with a different

study a finding in which they identified that a significant activation was observed during fMRI

experiments in the superior frontal sulcus mainly for conjunction search. The research

hypothesized that activation in the region took place could be a reflection of the working

memory that maintains and holds stimulus information in the mind so as to aid in the

identification of the target. Still, there was observed significant frontal activation that was

inclusive of the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the right dorsolateral prefrontal

cortex in positron emission tomography for spatial representations for attention during visual

search (Rahman, 2013). There is coincidence of the same region that have an association with

the spatial attention in the parietal cortex and those that have feature search. Moreover, the

frontal eye field which is positioned in the prefrontal cortex bilaterally has a significant role in

the movement of the saccadic eye as well as in the control of the visual attention.

A research into single cell recording and monkeys established that superior colliculus is in a way

involved in target selection in the process of visual search besides the initiation of various forms

of movement. In addition, it also made a suggestion that activation in the superior colliculus was

as a result of disengagement of attention which ensured that the subsequent stimulus could easily

be represented internally. There has been an established linkage between the pulvinar nucleus

which is located in the midbrain and the ability to have a direct attendance to a specific stimulus

during experiments of visual search while preventing attention to unattended stimuli. Findings

occurs during fMRI experiments in the superior parietal lobe alongside the right angular gyrus in

for the conjunction search.

On the contrary, Leonards, Sunaert, Vam Hecke and Orban (2000) came up with a different

study a finding in which they identified that a significant activation was observed during fMRI

experiments in the superior frontal sulcus mainly for conjunction search. The research

hypothesized that activation in the region took place could be a reflection of the working

memory that maintains and holds stimulus information in the mind so as to aid in the

identification of the target. Still, there was observed significant frontal activation that was

inclusive of the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the right dorsolateral prefrontal

cortex in positron emission tomography for spatial representations for attention during visual

search (Rahman, 2013). There is coincidence of the same region that have an association with

the spatial attention in the parietal cortex and those that have feature search. Moreover, the

frontal eye field which is positioned in the prefrontal cortex bilaterally has a significant role in

the movement of the saccadic eye as well as in the control of the visual attention.

A research into single cell recording and monkeys established that superior colliculus is in a way

involved in target selection in the process of visual search besides the initiation of various forms

of movement. In addition, it also made a suggestion that activation in the superior colliculus was

as a result of disengagement of attention which ensured that the subsequent stimulus could easily

be represented internally. There has been an established linkage between the pulvinar nucleus

which is located in the midbrain and the ability to have a direct attendance to a specific stimulus

during experiments of visual search while preventing attention to unattended stimuli. Findings

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

are Bender and Butter (1987) established that there was no engagement of the pulvinar nucleus

when a test on monkeys was conducted in the identification of search tasks.

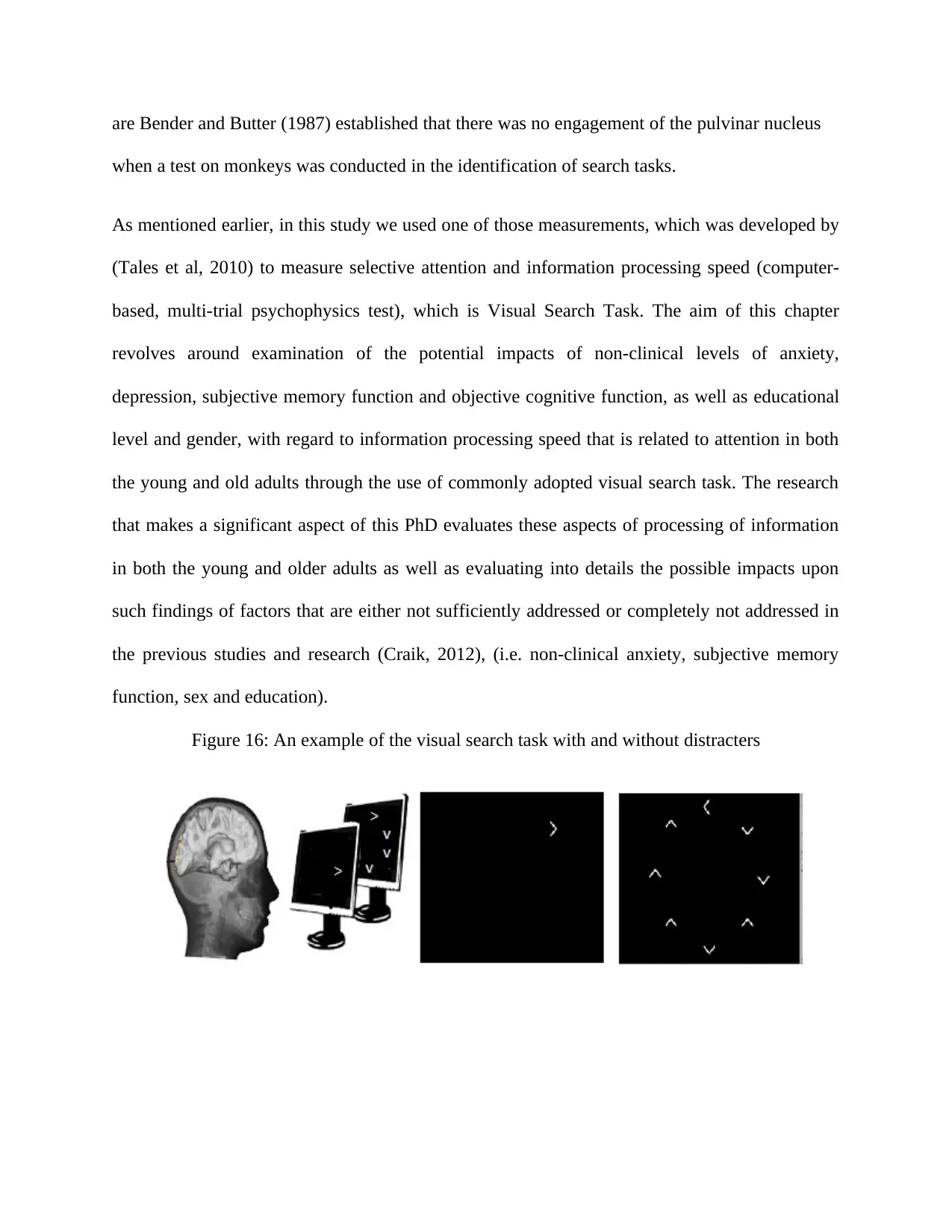

As mentioned earlier, in this study we used one of those measurements, which was developed by

(Tales et al, 2010) to measure selective attention and information processing speed (computer-

based, multi-trial psychophysics test), which is Visual Search Task. The aim of this chapter

revolves around examination of the potential impacts of non-clinical levels of anxiety,

depression, subjective memory function and objective cognitive function, as well as educational

level and gender, with regard to information processing speed that is related to attention in both

the young and old adults through the use of commonly adopted visual search task. The research

that makes a significant aspect of this PhD evaluates these aspects of processing of information

in both the young and older adults as well as evaluating into details the possible impacts upon

such findings of factors that are either not sufficiently addressed or completely not addressed in

the previous studies and research (Craik, 2012), (i.e. non-clinical anxiety, subjective memory

function, sex and education).

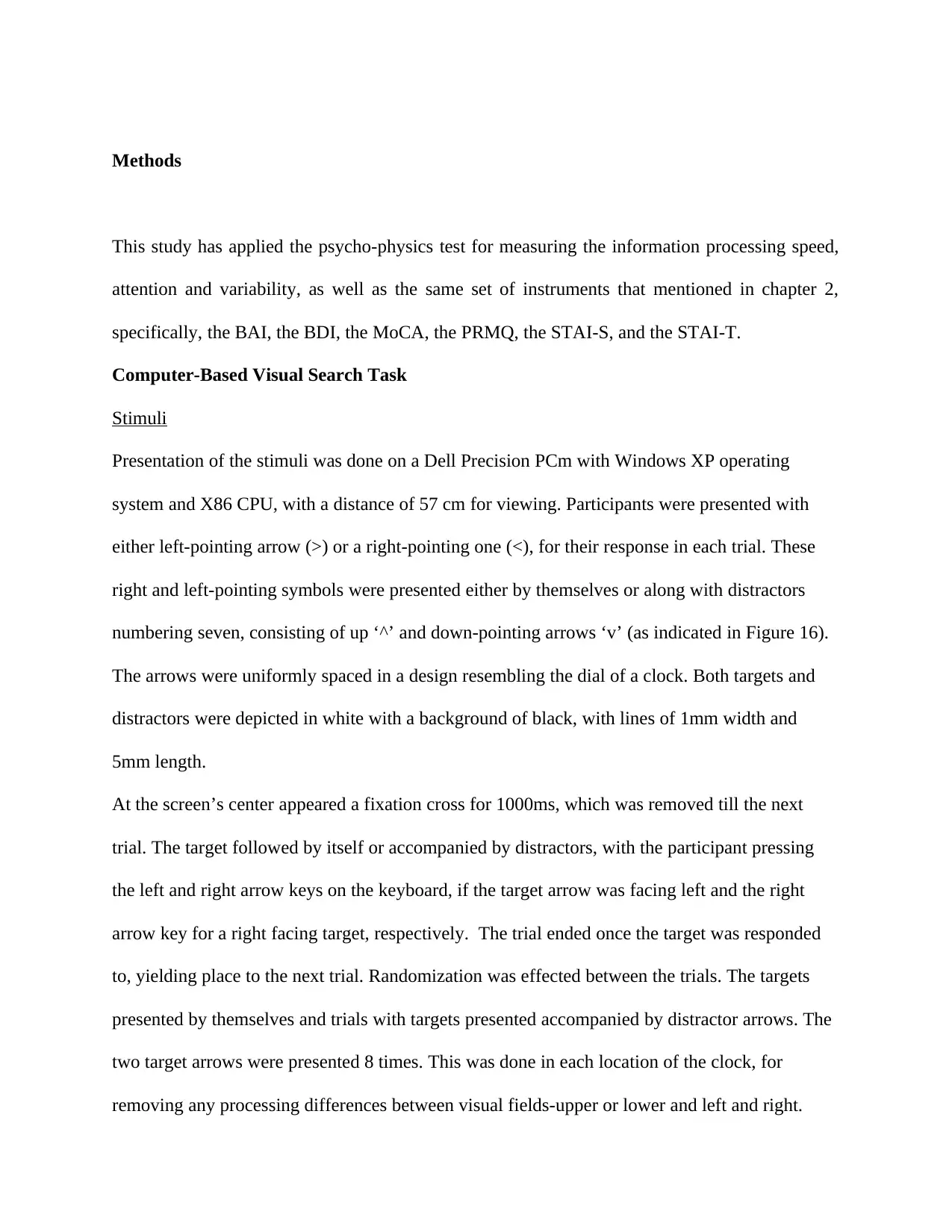

Figure 16: An example of the visual search task with and without distracters

when a test on monkeys was conducted in the identification of search tasks.

As mentioned earlier, in this study we used one of those measurements, which was developed by

(Tales et al, 2010) to measure selective attention and information processing speed (computer-

based, multi-trial psychophysics test), which is Visual Search Task. The aim of this chapter

revolves around examination of the potential impacts of non-clinical levels of anxiety,

depression, subjective memory function and objective cognitive function, as well as educational

level and gender, with regard to information processing speed that is related to attention in both

the young and old adults through the use of commonly adopted visual search task. The research

that makes a significant aspect of this PhD evaluates these aspects of processing of information

in both the young and older adults as well as evaluating into details the possible impacts upon

such findings of factors that are either not sufficiently addressed or completely not addressed in

the previous studies and research (Craik, 2012), (i.e. non-clinical anxiety, subjective memory

function, sex and education).

Figure 16: An example of the visual search task with and without distracters

Methods

This study has applied the psycho-physics test for measuring the information processing speed,

attention and variability, as well as the same set of instruments that mentioned in chapter 2,

specifically, the BAI, the BDI, the MoCA, the PRMQ, the STAI-S, and the STAI-T.

Computer-Based Visual Search Task

Stimuli

Presentation of the stimuli was done on a Dell Precision PCm with Windows XP operating

system and X86 CPU, with a distance of 57 cm for viewing. Participants were presented with

either left-pointing arrow (>) or a right-pointing one (<), for their response in each trial. These

right and left-pointing symbols were presented either by themselves or along with distractors

numbering seven, consisting of up ‘^’ and down-pointing arrows ‘v’ (as indicated in Figure 16).

The arrows were uniformly spaced in a design resembling the dial of a clock. Both targets and

distractors were depicted in white with a background of black, with lines of 1mm width and

5mm length.

At the screen’s center appeared a fixation cross for 1000ms, which was removed till the next

trial. The target followed by itself or accompanied by distractors, with the participant pressing

the left and right arrow keys on the keyboard, if the target arrow was facing left and the right

arrow key for a right facing target, respectively. The trial ended once the target was responded

to, yielding place to the next trial. Randomization was effected between the trials. The targets

presented by themselves and trials with targets presented accompanied by distractor arrows. The

two target arrows were presented 8 times. This was done in each location of the clock, for

removing any processing differences between visual fields-upper or lower and left and right.

This study has applied the psycho-physics test for measuring the information processing speed,

attention and variability, as well as the same set of instruments that mentioned in chapter 2,

specifically, the BAI, the BDI, the MoCA, the PRMQ, the STAI-S, and the STAI-T.

Computer-Based Visual Search Task

Stimuli

Presentation of the stimuli was done on a Dell Precision PCm with Windows XP operating

system and X86 CPU, with a distance of 57 cm for viewing. Participants were presented with

either left-pointing arrow (>) or a right-pointing one (<), for their response in each trial. These

right and left-pointing symbols were presented either by themselves or along with distractors

numbering seven, consisting of up ‘^’ and down-pointing arrows ‘v’ (as indicated in Figure 16).

The arrows were uniformly spaced in a design resembling the dial of a clock. Both targets and

distractors were depicted in white with a background of black, with lines of 1mm width and

5mm length.

At the screen’s center appeared a fixation cross for 1000ms, which was removed till the next

trial. The target followed by itself or accompanied by distractors, with the participant pressing

the left and right arrow keys on the keyboard, if the target arrow was facing left and the right

arrow key for a right facing target, respectively. The trial ended once the target was responded

to, yielding place to the next trial. Randomization was effected between the trials. The targets

presented by themselves and trials with targets presented accompanied by distractor arrows. The

two target arrows were presented 8 times. This was done in each location of the clock, for

removing any processing differences between visual fields-upper or lower and left and right.

Procedure

As instructed, the cross center formed the focus of participants between trials. Participants’

immediate and correct response was sought to the targets required (viz., the right and left arrows)

by pressing the same on a keyboard. A practice session of five to six trials was given to all

participants, prior to the restart of the program for testing. Participants who needed more practice

were allotted 5 more trials. This was followed by the testing phase, with 64 trials. Supervision of

the researcher supervision continued throughout the task, to check whether the participants were

pressing the correct buttons.

Data Processing

Inaccurate or outlying (below 150ms-representing faster than the natural reaction time, thus pre-

empting the stimulus, or above 10000ms-accompanie by attention deficit (Tales et al, 2010), as

called for by normal practice and precedents set by past research. There was no instance of

failure to respond to the trial on the part of any of the participants. Target-alone and Target plus

Distractors Trials were conducted for young old adults).

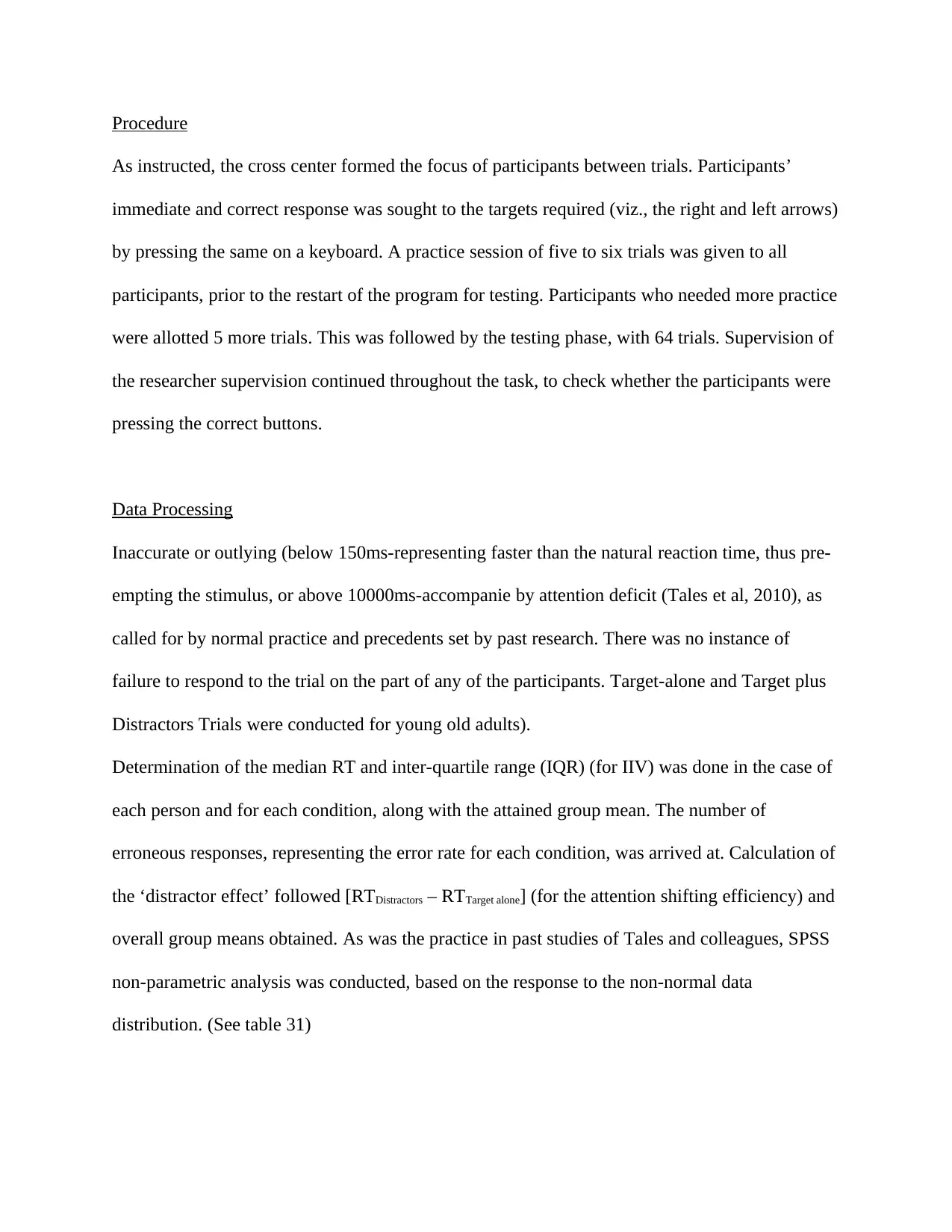

Determination of the median RT and inter-quartile range (IQR) (for IIV) was done in the case of

each person and for each condition, along with the attained group mean. The number of

erroneous responses, representing the error rate for each condition, was arrived at. Calculation of

the ‘distractor effect’ followed [RTDistractors – RTTarget alone] (for the attention shifting efficiency) and

overall group means obtained. As was the practice in past studies of Tales and colleagues, SPSS

non-parametric analysis was conducted, based on the response to the non-normal data

distribution. (See table 31)

As instructed, the cross center formed the focus of participants between trials. Participants’

immediate and correct response was sought to the targets required (viz., the right and left arrows)

by pressing the same on a keyboard. A practice session of five to six trials was given to all

participants, prior to the restart of the program for testing. Participants who needed more practice

were allotted 5 more trials. This was followed by the testing phase, with 64 trials. Supervision of

the researcher supervision continued throughout the task, to check whether the participants were

pressing the correct buttons.

Data Processing

Inaccurate or outlying (below 150ms-representing faster than the natural reaction time, thus pre-

empting the stimulus, or above 10000ms-accompanie by attention deficit (Tales et al, 2010), as

called for by normal practice and precedents set by past research. There was no instance of

failure to respond to the trial on the part of any of the participants. Target-alone and Target plus

Distractors Trials were conducted for young old adults).

Determination of the median RT and inter-quartile range (IQR) (for IIV) was done in the case of

each person and for each condition, along with the attained group mean. The number of

erroneous responses, representing the error rate for each condition, was arrived at. Calculation of

the ‘distractor effect’ followed [RTDistractors – RTTarget alone] (for the attention shifting efficiency) and

overall group means obtained. As was the practice in past studies of Tales and colleagues, SPSS

non-parametric analysis was conducted, based on the response to the non-normal data

distribution. (See table 31)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 31: Normality Test based on age

Age group

Kolmogorov-Smirnova Shapiro-Wilk

Statistic Df Sig. Statistic df Sig.

Target alone (50-80) older

adults .129 52 .030 .869 52 .000

(18-25) Young

group .141 52 .011 .889 52 .000

Target Plus

Distracters

(50-80) older

adults .190 52 .000 .876 52 .000

(18-25) Young

group .133 52 .023 .933 52 .006

Visual Search

Effect

(50-80) older

adults .131 52 .027 .955 52 .049

(18-25) Young

group .132 52 .024 .915 52 .001

Age group

Kolmogorov-Smirnova Shapiro-Wilk

Statistic Df Sig. Statistic df Sig.

Target alone (50-80) older

adults .129 52 .030 .869 52 .000

(18-25) Young

group .141 52 .011 .889 52 .000

Target Plus

Distracters

(50-80) older

adults .190 52 .000 .876 52 .000

(18-25) Young

group .133 52 .023 .933 52 .006

Visual Search

Effect

(50-80) older

adults .131 52 .027 .955 52 .049

(18-25) Young

group .132 52 .024 .915 52 .001

Results

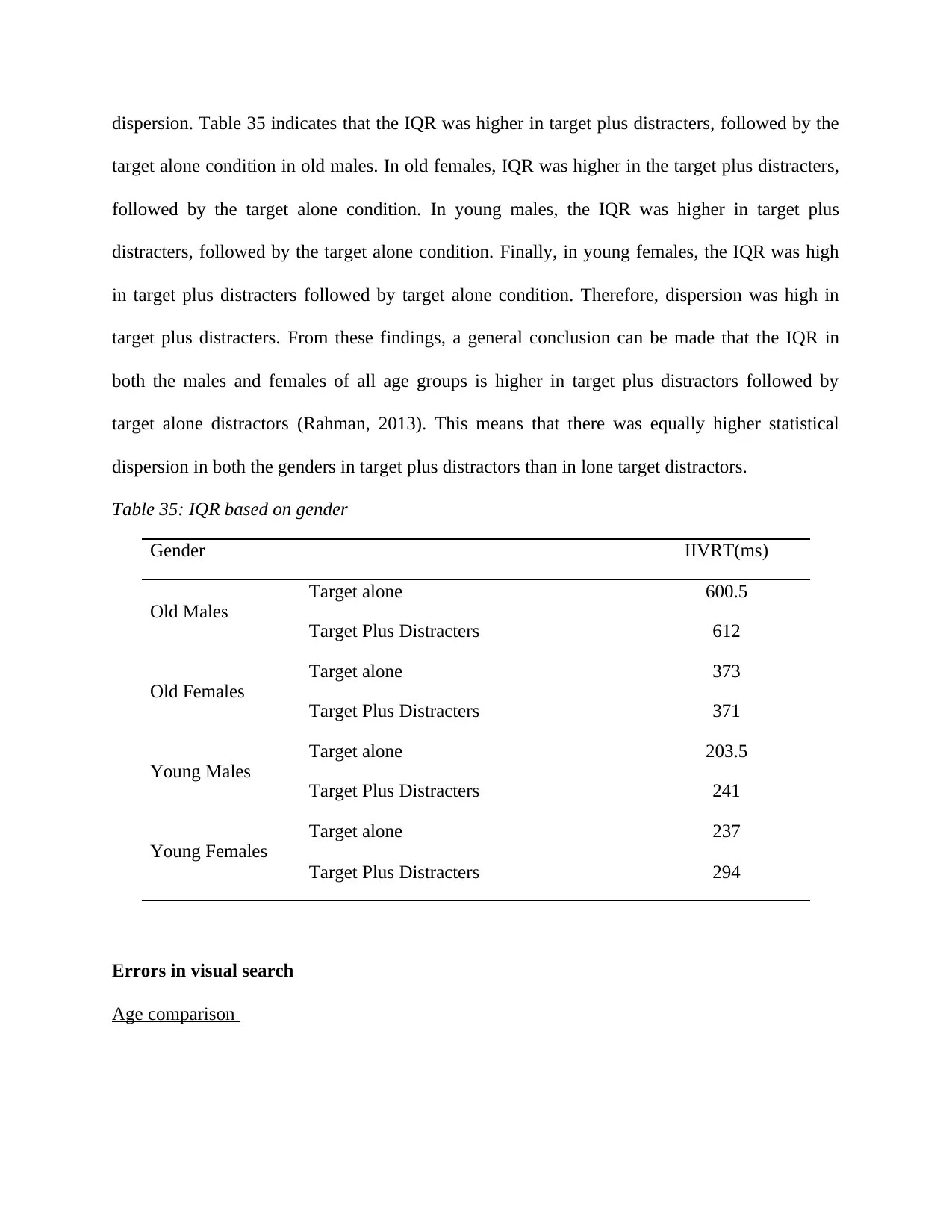

Visual search task: Information processing speed as per age group

Age comparison

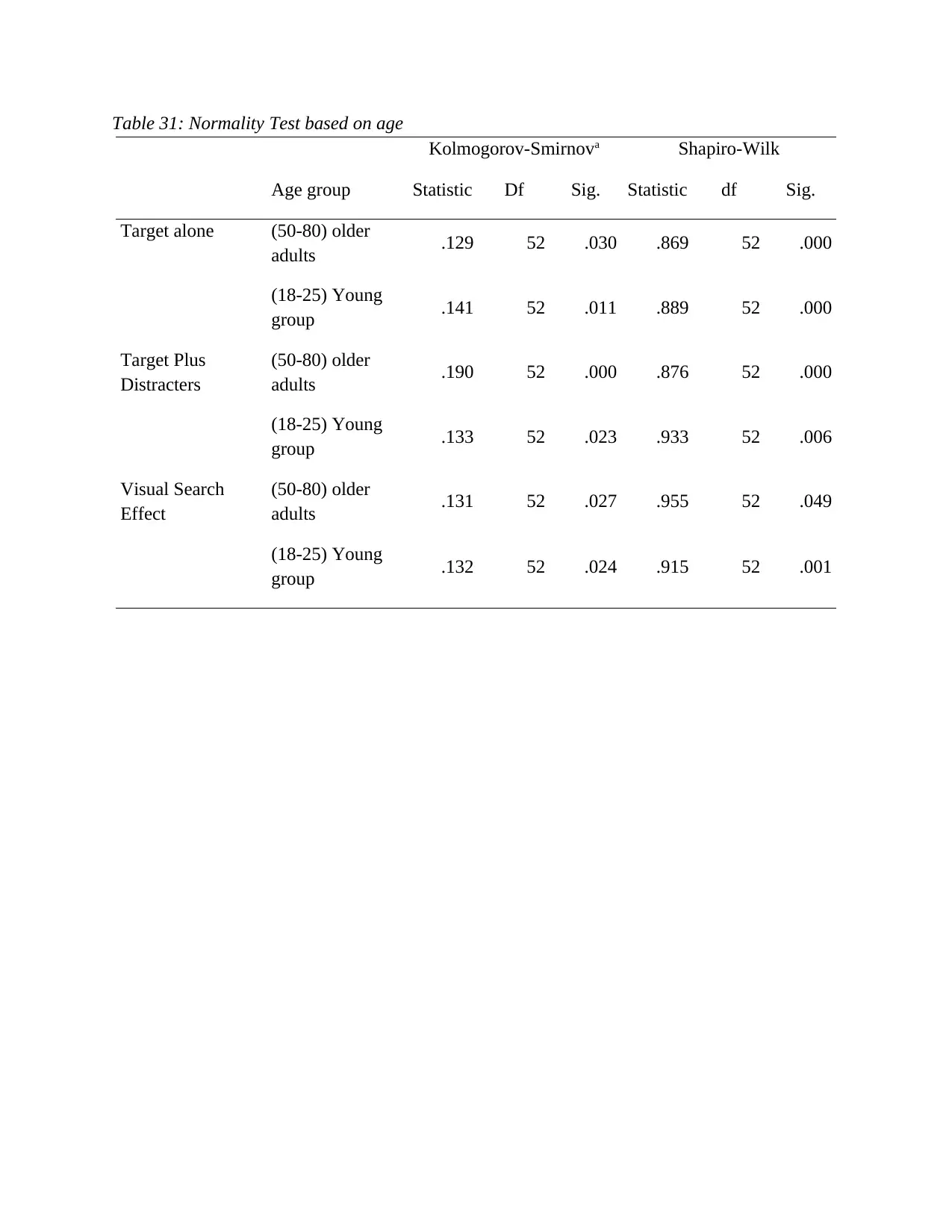

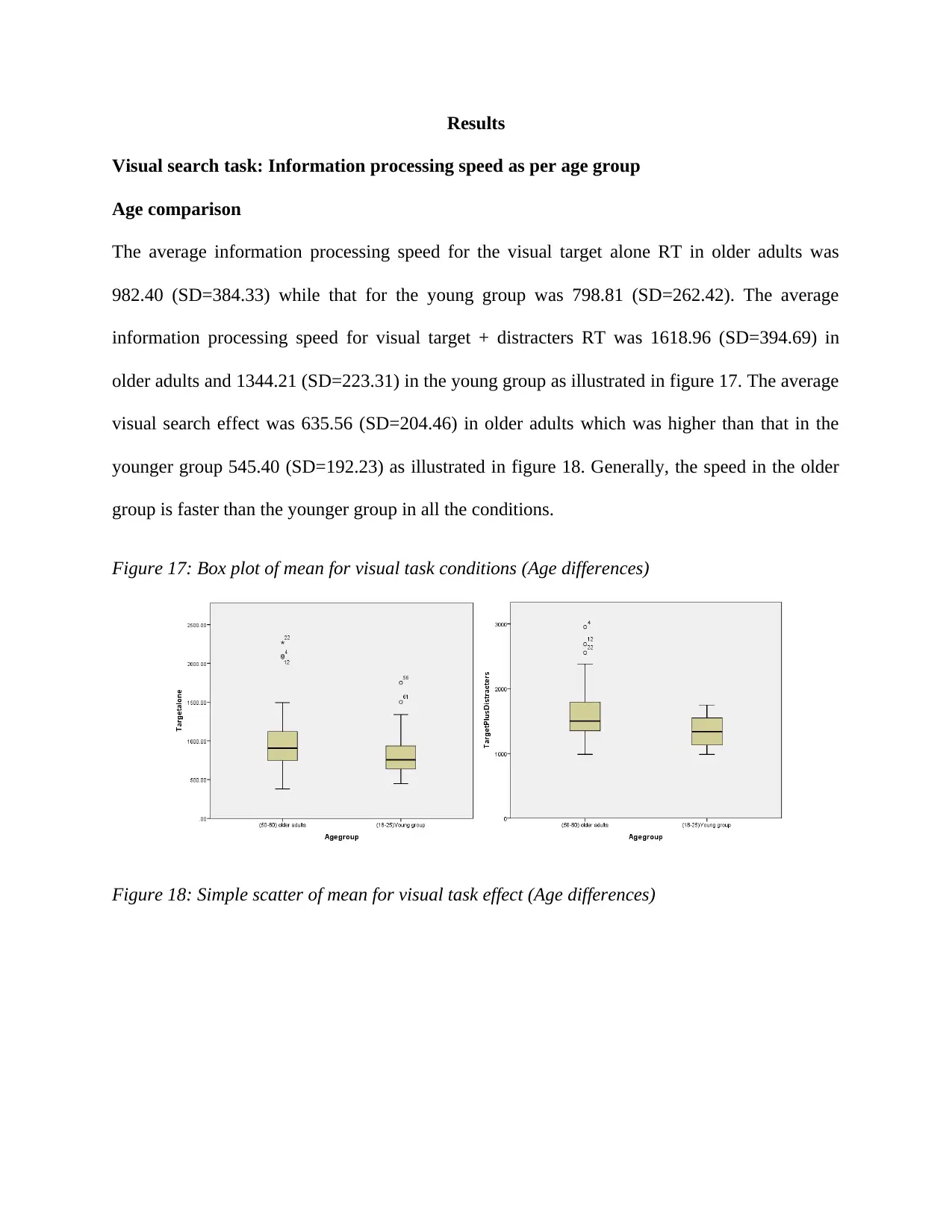

The average information processing speed for the visual target alone RT in older adults was

982.40 (SD=384.33) while that for the young group was 798.81 (SD=262.42). The average

information processing speed for visual target + distracters RT was 1618.96 (SD=394.69) in

older adults and 1344.21 (SD=223.31) in the young group as illustrated in figure 17. The average

visual search effect was 635.56 (SD=204.46) in older adults which was higher than that in the

younger group 545.40 (SD=192.23) as illustrated in figure 18. Generally, the speed in the older

group is faster than the younger group in all the conditions.

Figure 17: Box plot of mean for visual task conditions (Age differences)

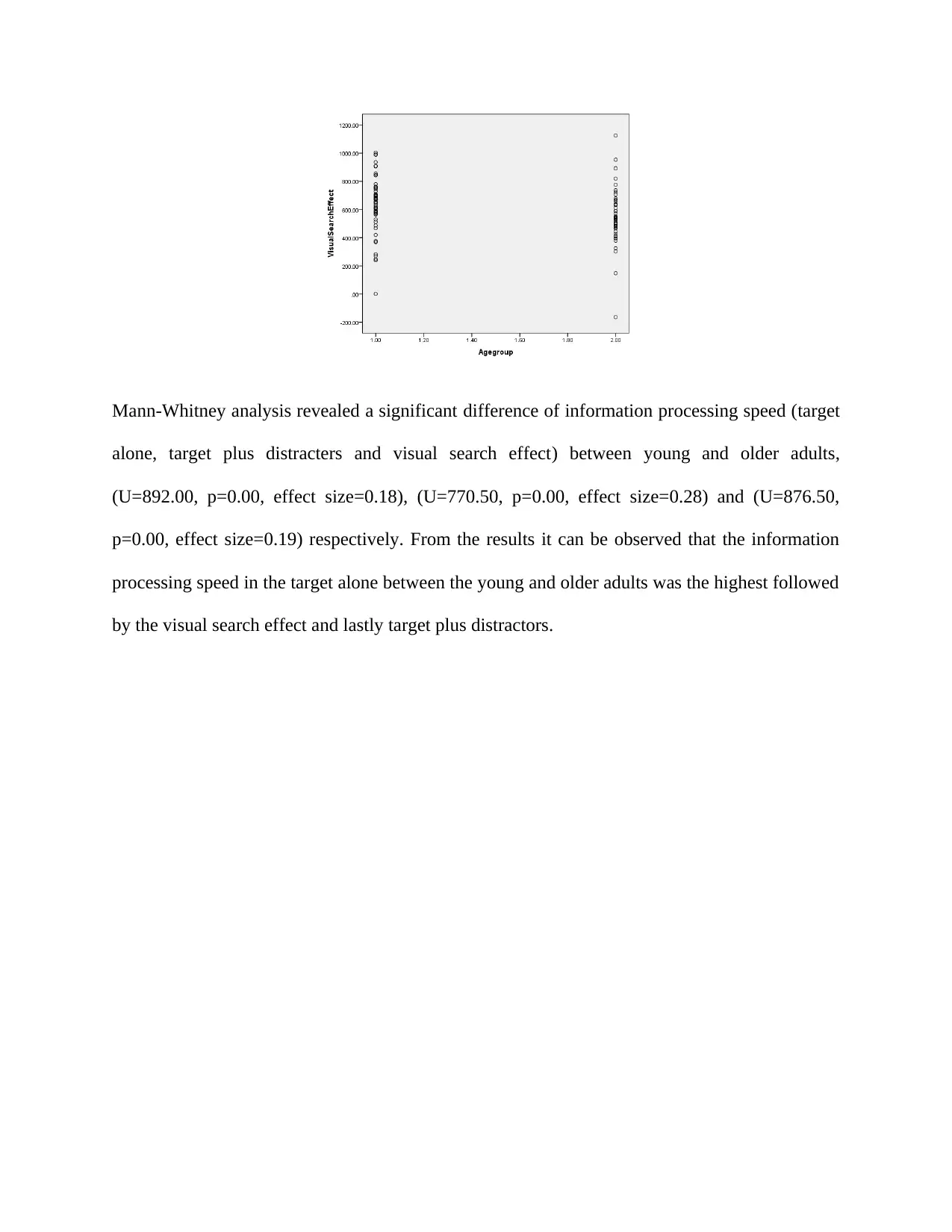

Figure 18: Simple scatter of mean for visual task effect (Age differences)

Visual search task: Information processing speed as per age group

Age comparison

The average information processing speed for the visual target alone RT in older adults was

982.40 (SD=384.33) while that for the young group was 798.81 (SD=262.42). The average

information processing speed for visual target + distracters RT was 1618.96 (SD=394.69) in

older adults and 1344.21 (SD=223.31) in the young group as illustrated in figure 17. The average

visual search effect was 635.56 (SD=204.46) in older adults which was higher than that in the

younger group 545.40 (SD=192.23) as illustrated in figure 18. Generally, the speed in the older

group is faster than the younger group in all the conditions.

Figure 17: Box plot of mean for visual task conditions (Age differences)

Figure 18: Simple scatter of mean for visual task effect (Age differences)

Mann-Whitney analysis revealed a significant difference of information processing speed (target

alone, target plus distracters and visual search effect) between young and older adults,

(U=892.00, p=0.00, effect size=0.18), (U=770.50, p=0.00, effect size=0.28) and (U=876.50,

p=0.00, effect size=0.19) respectively. From the results it can be observed that the information

processing speed in the target alone between the young and older adults was the highest followed

by the visual search effect and lastly target plus distractors.

alone, target plus distracters and visual search effect) between young and older adults,

(U=892.00, p=0.00, effect size=0.18), (U=770.50, p=0.00, effect size=0.28) and (U=876.50,

p=0.00, effect size=0.19) respectively. From the results it can be observed that the information

processing speed in the target alone between the young and older adults was the highest followed

by the visual search effect and lastly target plus distractors.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Visual search task: Information processing speed as per gender

Gender comparison

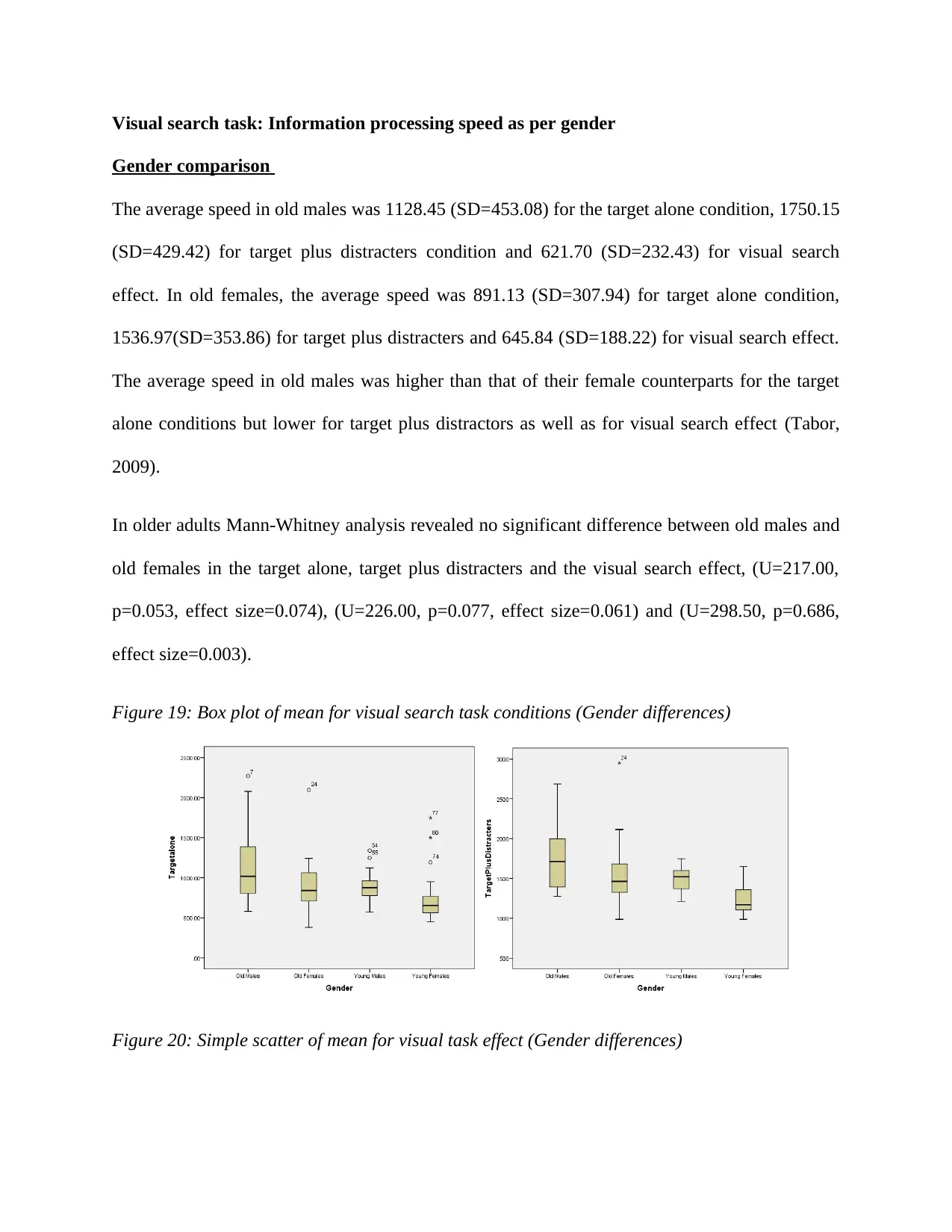

The average speed in old males was 1128.45 (SD=453.08) for the target alone condition, 1750.15

(SD=429.42) for target plus distracters condition and 621.70 (SD=232.43) for visual search

effect. In old females, the average speed was 891.13 (SD=307.94) for target alone condition,

1536.97(SD=353.86) for target plus distracters and 645.84 (SD=188.22) for visual search effect.

The average speed in old males was higher than that of their female counterparts for the target

alone conditions but lower for target plus distractors as well as for visual search effect (Tabor,

2009).

In older adults Mann-Whitney analysis revealed no significant difference between old males and

old females in the target alone, target plus distracters and the visual search effect, (U=217.00,

p=0.053, effect size=0.074), (U=226.00, p=0.077, effect size=0.061) and (U=298.50, p=0.686,

effect size=0.003).

Figure 19: Box plot of mean for visual search task conditions (Gender differences)

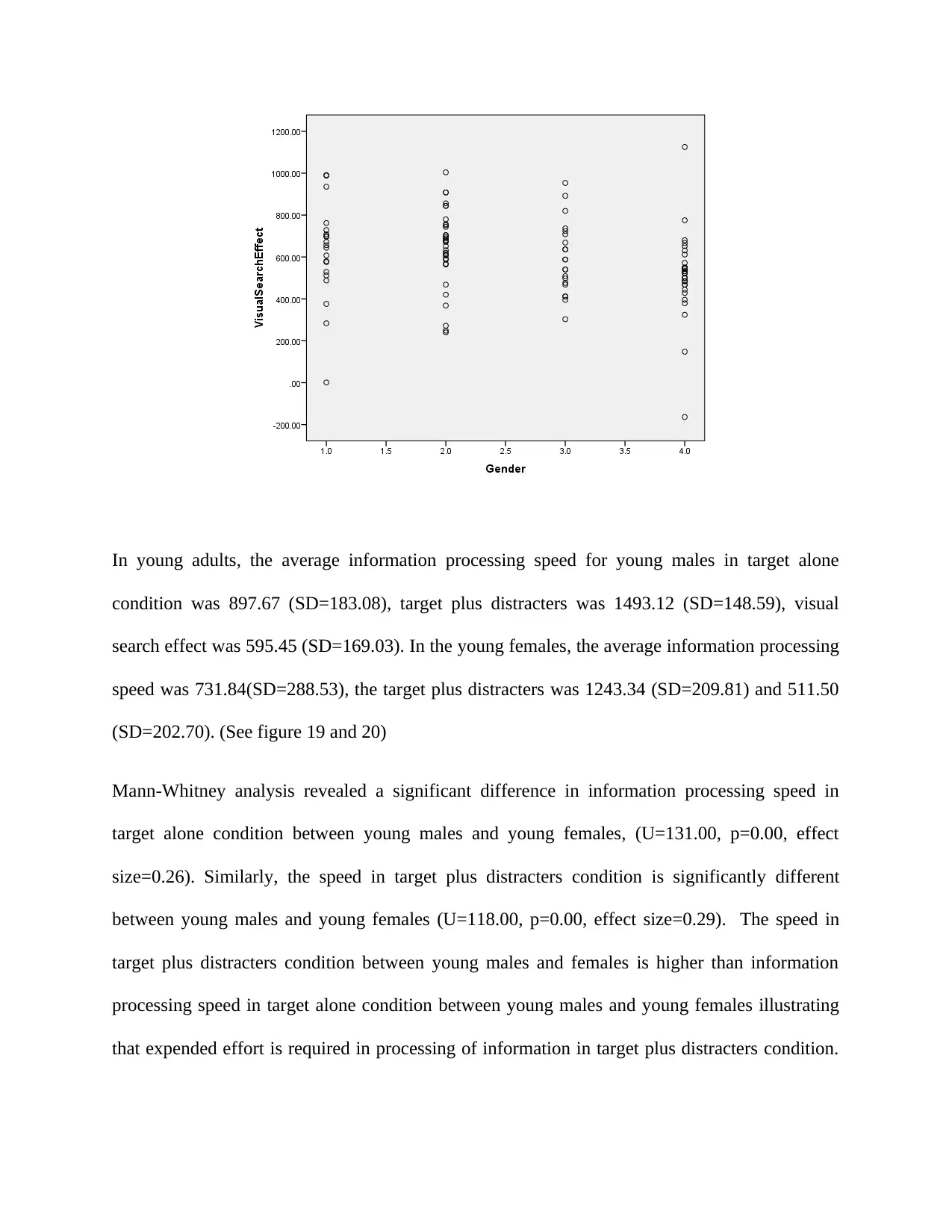

Figure 20: Simple scatter of mean for visual task effect (Gender differences)

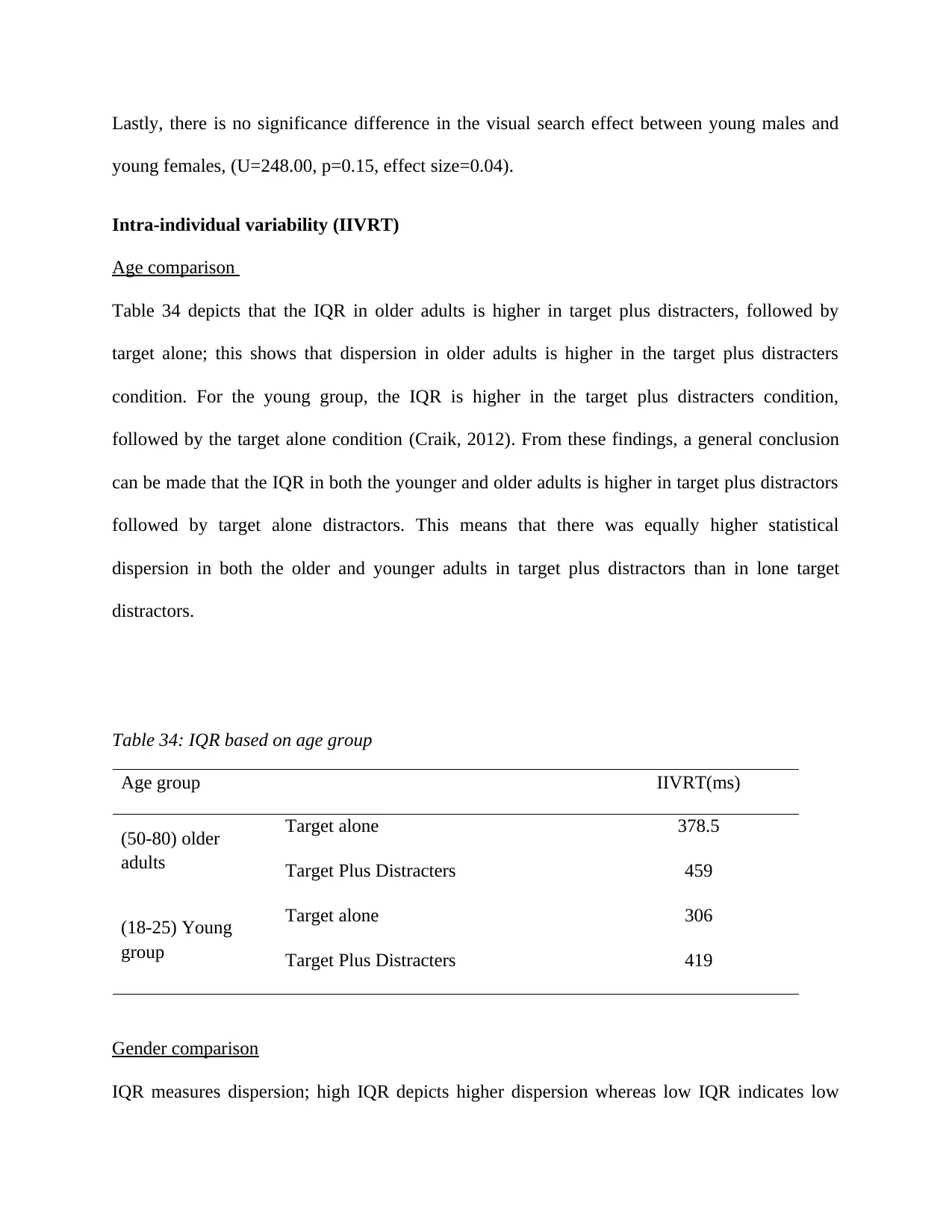

Gender comparison