A Systematic Review: Psychological Therapies for Autism & Disorders

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/07

|34

|13725

|76

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review investigates the efficacy of psychological therapies other than Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and co-occurring mental health (MH) conditions, specifically anxiety and depression. The review systematically examines Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT), Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS), and Mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) interventions. The analysis of fourteen studies meeting inclusion criteria suggests that these therapies can effectively reduce anxiety and depression in children, adolescents, young adults, and adults with autism, with some interventions also improving core autism symptoms and overall quality of life. The review highlights the need for future research to address methodological limitations and develop superior, evidence-based interventions to enhance the quality of life for individuals with ASD, as CBT and medication are not always effective for every autistic individual.

What is the evidence for psychological therapies

other than Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in autism

and co-occurring disorders? A systematic review.

other than Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in autism

and co-occurring disorders? A systematic review.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Contents

Abstract............................................................................................................................................................3

Introduction......................................................................................................................................................3

Methods............................................................................................................................................................6

Systematic search and Eligibility......................................................................................................................6

Data extraction.................................................................................................................................................7

Results..............................................................................................................................................................7

Discussion......................................................................................................................................................25

Conclusion......................................................................................................................................................28

References......................................................................................................................................................30

APPENDIX....................................................................................................................................................34

Abstract............................................................................................................................................................3

Introduction......................................................................................................................................................3

Methods............................................................................................................................................................6

Systematic search and Eligibility......................................................................................................................6

Data extraction.................................................................................................................................................7

Results..............................................................................................................................................................7

Discussion......................................................................................................................................................25

Conclusion......................................................................................................................................................28

References......................................................................................................................................................30

APPENDIX....................................................................................................................................................34

Abstract

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are more susceptible to stress, anxiety and depression

than typically developing individuals. Previous research suggests that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is

effective in reducing a myriad of psychological health problems in a wide variety of populations. However,

research identified other psychotherapies that might be just as effective as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

(CBT). However, it has been analysed that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is not that much effective for every

single individual therefore, it is needed to conduct investigation to identify the best suitable therapy to serve

individuals dealing with Autism and Co-occurring disorders. This review systematically investigated the

efficacy of Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT). Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), Program for the Education

and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS), and Mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) interventions in

reducing anxiety and depression in individuals with ASD. Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria. Results

indicate that the above-named psychotherapies reduce anxiety and depression in, children, adolescents,

young adults, and adults with autism. Additionally, some of the interventions identified reduced core autism

symptoms and improved overall quality of life. Therefore, considering different interventions like

Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), Achievement Anxiety Test (AAT), Mindfulness-based therapy (MBT),

Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) and other would effectively lead

individuals dealing with autism and co-occurring disorders to gain positive changes in both mental and

physical conditions. Future research should address the methodological limitations of the studies in this

review to develop superior interventions that are to be considered evidence-based practice aimed at

enhancing the quality of life of individuals with ASD.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD or autism) is a neuro developmental disorder characterized by

impairments in speech, social communication, social functioning, and repetitive or stereotyped behaviour

(Lai et al., 2019; Hossain et al., 2020). This is an neurodevelopmentalal disorder and symptoms usually

appear in the first two years of life, although may not become obvious until social demands outweigh

capacity (Hepburn et al., 2014; Hofyander et al., 2009; Maddox et al., 2015). The most recent measurements

indicate that approximately 1% of the global population hold an autism diagnosis (Lai et al., 2019; Lyall et

al., 2017, Hossain et al., 2020).

It has been widely accepted that individuals with autism develop co-occurring mental health (MH)

conditions. Figures show that 70% of individuals on the autism spectrum develop at least one cooccurring

MH condition, with at least 50% of individuals developing two or more (Hossain et al., 2020; Lai,

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are more susceptible to stress, anxiety and depression

than typically developing individuals. Previous research suggests that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is

effective in reducing a myriad of psychological health problems in a wide variety of populations. However,

research identified other psychotherapies that might be just as effective as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

(CBT). However, it has been analysed that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is not that much effective for every

single individual therefore, it is needed to conduct investigation to identify the best suitable therapy to serve

individuals dealing with Autism and Co-occurring disorders. This review systematically investigated the

efficacy of Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT). Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), Program for the Education

and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS), and Mindfulness-based therapy (MBT) interventions in

reducing anxiety and depression in individuals with ASD. Fourteen studies met inclusion criteria. Results

indicate that the above-named psychotherapies reduce anxiety and depression in, children, adolescents,

young adults, and adults with autism. Additionally, some of the interventions identified reduced core autism

symptoms and improved overall quality of life. Therefore, considering different interventions like

Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), Achievement Anxiety Test (AAT), Mindfulness-based therapy (MBT),

Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) and other would effectively lead

individuals dealing with autism and co-occurring disorders to gain positive changes in both mental and

physical conditions. Future research should address the methodological limitations of the studies in this

review to develop superior interventions that are to be considered evidence-based practice aimed at

enhancing the quality of life of individuals with ASD.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD or autism) is a neuro developmental disorder characterized by

impairments in speech, social communication, social functioning, and repetitive or stereotyped behaviour

(Lai et al., 2019; Hossain et al., 2020). This is an neurodevelopmentalal disorder and symptoms usually

appear in the first two years of life, although may not become obvious until social demands outweigh

capacity (Hepburn et al., 2014; Hofyander et al., 2009; Maddox et al., 2015). The most recent measurements

indicate that approximately 1% of the global population hold an autism diagnosis (Lai et al., 2019; Lyall et

al., 2017, Hossain et al., 2020).

It has been widely accepted that individuals with autism develop co-occurring mental health (MH)

conditions. Figures show that 70% of individuals on the autism spectrum develop at least one cooccurring

MH condition, with at least 50% of individuals developing two or more (Hossain et al., 2020; Lai,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Lombardo, & Baron-Cohen, 2014; Ameis & Szatmari, 2015). However, the above mentioned information

specifically varies from area to area (geographical locations). One of the most recent systematic reviews in

the field, reported that the pooled prevalence is 28% for ADHD, 20% for anxiety disorders, 13% for sleep-

wake disorders, 12% for disruptive, impulsive-control, and conduct disorders, 1% for depressive disorders,

9% for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 5% for bipolar disorders, and 4% for schizophrenia disorders (Lai et

al., 2019).

Arguably, the most prevalent MH conditions among the autistic population are anxiety and

depressive disorders (Uljarevic et al., 2019; Mazzone et al., 2012). On the other hand, as mentioned above

approximately 13% of autistic population is dealing with sleep-wake disorders, around 12% of the

individuals are going through disruptive, conduct disorders and impulsive-control, 1% for depressive

disorders, 9% for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Therefore, it can easily be said that these predict lower

quality of life, increased service use, significant impairment in adaptive, family, academic, and social

functioning (Olatunji, Eklund, & Howley, 2007; Cadman et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2012; Higa-McMillan et

al., 2018). According to Uljarevic et al., 2016 and van Steensel et al., 2011 around 40% of youth (children

and adolescents) diagnosed with autism develop anxiety disorders. This rate is higher compared to the

general population (Gadow et al., 2005) but also higher compared to other neurodevelopmental disorders

(Rodgers et al., 2012). Research on adults on the spectrum suggest that around 53.6% meet the diagnostic

symptoms for clinical anxiety (Buck et al., 2014; Lever & Geurts, 2016; Roy et al., 2015), whereas only 35%

meet the diagnostic criteria for symptoms of depression or depressive disorders (Cassidy et al., 2014; Russell

et al., 2015; Wigham et al., 2017).

Given the regularity with which anxiety and depression co-occur in ASD, in combination with their

effect on functioning, quality of life, and adult outcome, it is important to consider how best to prevent and

manage these disorders among adults and children with ASD (Higa-McMillan et al., 2018). To date, and

recommended by NICE (2013), the most used treatments are talk therapy, such as Cognitive Behavioural

Therapy (CBT) (Propper & Orlik, 2014; Williams, Wheeler, Silove, & Hazell, 2010) and psychotropic

medication (Lake et al., 2015; Maddox et al., 2018).

CBT assumes that cognitive factors support psychological distress and MH disorders, and that

challenging behaviour and emotional distress are maintained by maladaptive cognitions, such as general

beliefs about the self, the world, and the future. CBT sessions are carried out individually (Thyme et al.,

2006; Beebe, Gelfant, & Bender, 2010), in group (Gold, Wigram, & Elefant, 2006) or a mix between group

and individual sessions (Keng, Smiski, & Robins, 2011). During treatment, therapists are challenging these

maladaptive cognitions to change the associated beliefs and thoughts, and trialling new behavioural

approaches to ultimately reduce the symptoms, improve functioning, and prevent remission of the disorder

(Hoffman et al., 2012). Hence, the patient assumes the role of a decision-maker in a problem-solving

situation where they challenge and test the authenticity of their maladaptive cognitions and adjust

specifically varies from area to area (geographical locations). One of the most recent systematic reviews in

the field, reported that the pooled prevalence is 28% for ADHD, 20% for anxiety disorders, 13% for sleep-

wake disorders, 12% for disruptive, impulsive-control, and conduct disorders, 1% for depressive disorders,

9% for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 5% for bipolar disorders, and 4% for schizophrenia disorders (Lai et

al., 2019).

Arguably, the most prevalent MH conditions among the autistic population are anxiety and

depressive disorders (Uljarevic et al., 2019; Mazzone et al., 2012). On the other hand, as mentioned above

approximately 13% of autistic population is dealing with sleep-wake disorders, around 12% of the

individuals are going through disruptive, conduct disorders and impulsive-control, 1% for depressive

disorders, 9% for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Therefore, it can easily be said that these predict lower

quality of life, increased service use, significant impairment in adaptive, family, academic, and social

functioning (Olatunji, Eklund, & Howley, 2007; Cadman et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2012; Higa-McMillan et

al., 2018). According to Uljarevic et al., 2016 and van Steensel et al., 2011 around 40% of youth (children

and adolescents) diagnosed with autism develop anxiety disorders. This rate is higher compared to the

general population (Gadow et al., 2005) but also higher compared to other neurodevelopmental disorders

(Rodgers et al., 2012). Research on adults on the spectrum suggest that around 53.6% meet the diagnostic

symptoms for clinical anxiety (Buck et al., 2014; Lever & Geurts, 2016; Roy et al., 2015), whereas only 35%

meet the diagnostic criteria for symptoms of depression or depressive disorders (Cassidy et al., 2014; Russell

et al., 2015; Wigham et al., 2017).

Given the regularity with which anxiety and depression co-occur in ASD, in combination with their

effect on functioning, quality of life, and adult outcome, it is important to consider how best to prevent and

manage these disorders among adults and children with ASD (Higa-McMillan et al., 2018). To date, and

recommended by NICE (2013), the most used treatments are talk therapy, such as Cognitive Behavioural

Therapy (CBT) (Propper & Orlik, 2014; Williams, Wheeler, Silove, & Hazell, 2010) and psychotropic

medication (Lake et al., 2015; Maddox et al., 2018).

CBT assumes that cognitive factors support psychological distress and MH disorders, and that

challenging behaviour and emotional distress are maintained by maladaptive cognitions, such as general

beliefs about the self, the world, and the future. CBT sessions are carried out individually (Thyme et al.,

2006; Beebe, Gelfant, & Bender, 2010), in group (Gold, Wigram, & Elefant, 2006) or a mix between group

and individual sessions (Keng, Smiski, & Robins, 2011). During treatment, therapists are challenging these

maladaptive cognitions to change the associated beliefs and thoughts, and trialling new behavioural

approaches to ultimately reduce the symptoms, improve functioning, and prevent remission of the disorder

(Hoffman et al., 2012). Hence, the patient assumes the role of a decision-maker in a problem-solving

situation where they challenge and test the authenticity of their maladaptive cognitions and adjust

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

challenging behaviour patterns. Thus, CBT creates a model of intervention by combining cognitive,

behavioural, and emotion-focused techniques (Hoffman, 2011).

Including this, the best evidence for CBT has been found as an intervention for anxiety disorders

(Casidy, Bradley, Shaw, & Baron-Cohen 2018) and found moderate to large effect sizes (Ben-Sasson et al.,

2008; Kim, Szatmari, Bryson, Streiner, & Wilson, 2000; Mayes, Calhoun, Murray, & Zahid, 2011). Parents

of children with ASD reported an improvement in anxiety symptoms (Danial and Wood, 2013; Wood,

Drahota, & Sze, 2009; Wood, Fujii, & Renno, 2011). There is also some evidence that the same

improvement was observed in adults on the spectrum (Cardaciotto and Herbert, 2004; Weiss and Lunsky,

2010). A recent meta-analysis reported a small to medium treatment effect for management of comorbid

affective disorders in ASD (Weston, Hodgekins, & Langdon, 2016). Surprisingly, one quasi-experimental

design study reported a positive outcome on depression, but no effect was reported on anxiety (McGillivray

and Evert, 2014).

On the other hand, most autistic individuals (both children and adults) with co-occurring anxiety

and/or depression are readily prescribed psychotropic and antidepressant medication or benzodiazepine

(Rosenberg et al. 2010; Coury et al. 2012; Logan et al. 2012; Memari et al. 2012; Schubart et al. 2013;

Spencer et al. 2013; Hsia et al. 2014). By the time they reach adulthood, around 75% of children and

adolescents on the spectrum have already been prescribed psychotropic medication (Esbensen et al. 2009;

Spencer et al. 2013). The study of Maddox et al., (2018), comprising of 268 individuals with ASD (age

range: 18-65 years), reported that 51.1% were taking antidepressant medication, 39.6% antipsychotic

medication, and 28.0% benzodiazepine. Furthermore, an online survey (Gotham et al., 2015) stated that out

of 255 adults who self-reported their treatment 61% were taking medication, and out of 143 adults whose

information about treatment was provided by their caregivers, 72% were taking medication.

Anxiety is considered to be one of the most common disorder which can be identified in teenagers where,

ASD and Core Social Disability among them can easily be treated in much effective and in efficient manner

considering combined treatment approaches. It has been analysed that, randomized controlled trial has given

ample number of benefits to evaluate, pull out feasible information and preliminary outcomes considering

Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention (MASSI) program. Including this, it can be said that the

treatment considering the MASSI Program it was pretty much acceptable to both autistic population and

families as well. Approximately 16% of the improvement can be seen within Autism spectrum disorder

considering social impairment. Due to the particular intervention, anxiety symptoms declined by 26 %.

However, it can be said that these alterations are not statistically significant. Therefore, it cannot be said that

if MASSI is an effective program to treat individuals dealing with ASD. Away with this, CBT and

psychotropic medication have been found to not be effective for every autistic individual. Moreover, CBT is

not the only psychological therapy recommended for the same mental health conditions (White et al., 2018).

behavioural, and emotion-focused techniques (Hoffman, 2011).

Including this, the best evidence for CBT has been found as an intervention for anxiety disorders

(Casidy, Bradley, Shaw, & Baron-Cohen 2018) and found moderate to large effect sizes (Ben-Sasson et al.,

2008; Kim, Szatmari, Bryson, Streiner, & Wilson, 2000; Mayes, Calhoun, Murray, & Zahid, 2011). Parents

of children with ASD reported an improvement in anxiety symptoms (Danial and Wood, 2013; Wood,

Drahota, & Sze, 2009; Wood, Fujii, & Renno, 2011). There is also some evidence that the same

improvement was observed in adults on the spectrum (Cardaciotto and Herbert, 2004; Weiss and Lunsky,

2010). A recent meta-analysis reported a small to medium treatment effect for management of comorbid

affective disorders in ASD (Weston, Hodgekins, & Langdon, 2016). Surprisingly, one quasi-experimental

design study reported a positive outcome on depression, but no effect was reported on anxiety (McGillivray

and Evert, 2014).

On the other hand, most autistic individuals (both children and adults) with co-occurring anxiety

and/or depression are readily prescribed psychotropic and antidepressant medication or benzodiazepine

(Rosenberg et al. 2010; Coury et al. 2012; Logan et al. 2012; Memari et al. 2012; Schubart et al. 2013;

Spencer et al. 2013; Hsia et al. 2014). By the time they reach adulthood, around 75% of children and

adolescents on the spectrum have already been prescribed psychotropic medication (Esbensen et al. 2009;

Spencer et al. 2013). The study of Maddox et al., (2018), comprising of 268 individuals with ASD (age

range: 18-65 years), reported that 51.1% were taking antidepressant medication, 39.6% antipsychotic

medication, and 28.0% benzodiazepine. Furthermore, an online survey (Gotham et al., 2015) stated that out

of 255 adults who self-reported their treatment 61% were taking medication, and out of 143 adults whose

information about treatment was provided by their caregivers, 72% were taking medication.

Anxiety is considered to be one of the most common disorder which can be identified in teenagers where,

ASD and Core Social Disability among them can easily be treated in much effective and in efficient manner

considering combined treatment approaches. It has been analysed that, randomized controlled trial has given

ample number of benefits to evaluate, pull out feasible information and preliminary outcomes considering

Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention (MASSI) program. Including this, it can be said that the

treatment considering the MASSI Program it was pretty much acceptable to both autistic population and

families as well. Approximately 16% of the improvement can be seen within Autism spectrum disorder

considering social impairment. Due to the particular intervention, anxiety symptoms declined by 26 %.

However, it can be said that these alterations are not statistically significant. Therefore, it cannot be said that

if MASSI is an effective program to treat individuals dealing with ASD. Away with this, CBT and

psychotropic medication have been found to not be effective for every autistic individual. Moreover, CBT is

not the only psychological therapy recommended for the same mental health conditions (White et al., 2018).

Research Aim: The aim of the present systematic review is “To identify and evaluate the existing

evidence base for psychological therapies used in the treatment of co-occurring MH conditions in autistic

population.”

Research Objectives:

To understand the concept of autism and co-occurring disorders.

To identify the different psychological therapies used in the treatment of co-occurring MH

conditions in autistic population.

To analyse the benefits of using various therapies like Animal-assisted therapy (AAT), Dance-

Movement Therapy (DMT), Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills

(PEERS), and Mindfulness based stress reduction therapy (MBSR) while treating Autism and co-

occurring disorders.

The particular focus is on psychological therapies used in the treatment of anxiety and depression

disorders. Different psychotherapies, such as animal-assisted therapy, dance-movement therapy (DMT),

Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) and Mindfulness based stress

reduction therapy (MBSR) have been identified. These studies reported improvements in anxiety and

depressive symptoms among the autistic population. Although small, the body of research on DMT argues

that such therapy has a positive impact on lowering depression and anxiety symptoms and improving social

functioning for both children and adults (Dunphy, Mullane, & Jacobsson, 2013). Keng et al., (2011)

reviewed 16 RCTs on mindfulness and its impact on the autism spectrum and highlighted substantial

improvement in positive affect, empathy, and quality of life.

Methods

Systematic search and Eligibility

In order to identify the studies, several literature searches have been performed in the following

databases: Embase, PsycInfo, and Medline. Search included key words such as autism (and auti*), treatment,

management, psychotherapy (and psychotherap*), anxiety, depression, MH, children, youth, adolescents,

and adults. These words were also combined to better the database search. For any study to be included, it

had to meet the following criteria: Studies to be in English Language, Studies to be published between 2008

and 2020. The reason that came in front of considering publications from 2008 is because from overall

estimated prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD or autism) among the 14 ADDM sites was 11.3 per

1,000 (one in 88) children aged 8 years who were living in these communities during 2008. Away with this,

the last date of data which is being gathered is the May month ending of 2020.

All studies had to include children or adolescents or Adults, Studies to look at psychological

treatment of comorbid anxiety or Depression, Studies published only in peer review Journals Participants

evidence base for psychological therapies used in the treatment of co-occurring MH conditions in autistic

population.”

Research Objectives:

To understand the concept of autism and co-occurring disorders.

To identify the different psychological therapies used in the treatment of co-occurring MH

conditions in autistic population.

To analyse the benefits of using various therapies like Animal-assisted therapy (AAT), Dance-

Movement Therapy (DMT), Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills

(PEERS), and Mindfulness based stress reduction therapy (MBSR) while treating Autism and co-

occurring disorders.

The particular focus is on psychological therapies used in the treatment of anxiety and depression

disorders. Different psychotherapies, such as animal-assisted therapy, dance-movement therapy (DMT),

Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS) and Mindfulness based stress

reduction therapy (MBSR) have been identified. These studies reported improvements in anxiety and

depressive symptoms among the autistic population. Although small, the body of research on DMT argues

that such therapy has a positive impact on lowering depression and anxiety symptoms and improving social

functioning for both children and adults (Dunphy, Mullane, & Jacobsson, 2013). Keng et al., (2011)

reviewed 16 RCTs on mindfulness and its impact on the autism spectrum and highlighted substantial

improvement in positive affect, empathy, and quality of life.

Methods

Systematic search and Eligibility

In order to identify the studies, several literature searches have been performed in the following

databases: Embase, PsycInfo, and Medline. Search included key words such as autism (and auti*), treatment,

management, psychotherapy (and psychotherap*), anxiety, depression, MH, children, youth, adolescents,

and adults. These words were also combined to better the database search. For any study to be included, it

had to meet the following criteria: Studies to be in English Language, Studies to be published between 2008

and 2020. The reason that came in front of considering publications from 2008 is because from overall

estimated prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD or autism) among the 14 ADDM sites was 11.3 per

1,000 (one in 88) children aged 8 years who were living in these communities during 2008. Away with this,

the last date of data which is being gathered is the May month ending of 2020.

All studies had to include children or adolescents or Adults, Studies to look at psychological

treatment of comorbid anxiety or Depression, Studies published only in peer review Journals Participants

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

within the identified studies had to have an autism diagnosis. On the other hand, those individuals will not be

considered who are already dealing with chronic diseases. Before going ahead and including the final studies

in the review, a list of 50 and 100 study titles along with the inclusion criteria were checked by supervisor

and peers as an extra form of database search validation. Including this, consent form is also going to be

given to them in order to keep up their trust and reduce any risks of disagreement and so on.

Data extraction

For each included study, a data extraction form was put in place. The form included details such as

participant demographics (number of participants included in each study, age range, no of males and

females, and descriptive statistics), methods (aim of the study, intervention type, duration of participation),

and procedure (duration and frequency of treatment, and assessment tools used). This information along with

the study characteristics (such as author, year, and title) can be found in Table 1.

Quality Rating (With 5 being the highest)

Age range 3

no of males and females 4

descriptive statistics 5

Results

Study selection

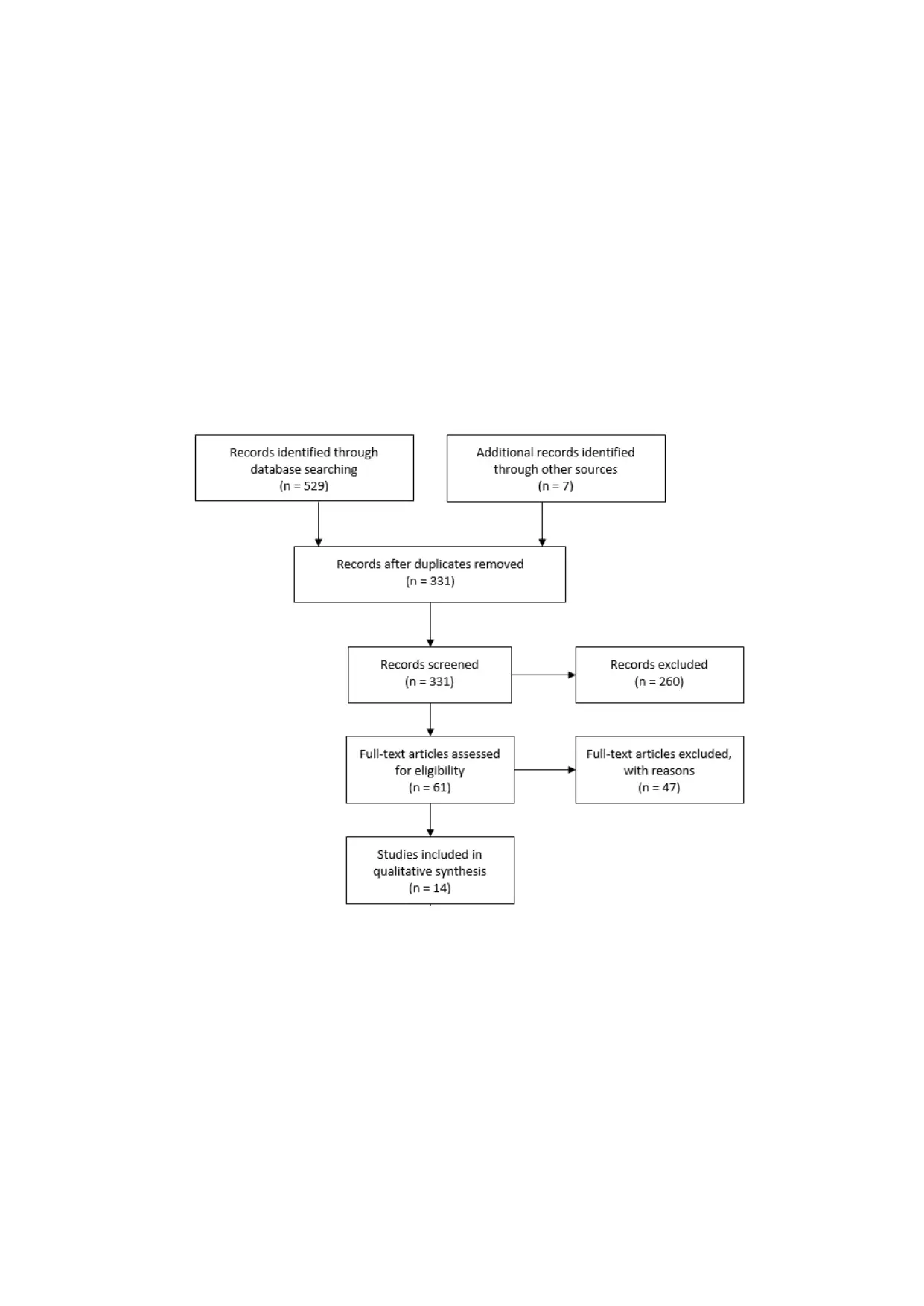

The total number of references identified through database search is 529 and after duplicates were

removed, 331 studies were screened against the eligibility criteria. Studies were excluded initially based on

title, and subsequently some full text studies were also excluded. Factors determining the exclusion of

studies are related to reasons such as the target sample was not autistic population, and the intervention was

not targeting anxiety or depression, but rather cognitive systems or motor skills. Studies that targeted social

functioning and social skills were included. The final sample included 14 studies – 4 studies were Animal-

Assisted Intervention, 1 study was a Dance-Movement intervention, 4 studies were PEERS intervention, and

5 studies were MBT intervention. The PRISMA flowchart (Moher et al., 2009; Liberati et al., 2009) of the

systematic search results and the included studies is presented in Fig 1.

considered who are already dealing with chronic diseases. Before going ahead and including the final studies

in the review, a list of 50 and 100 study titles along with the inclusion criteria were checked by supervisor

and peers as an extra form of database search validation. Including this, consent form is also going to be

given to them in order to keep up their trust and reduce any risks of disagreement and so on.

Data extraction

For each included study, a data extraction form was put in place. The form included details such as

participant demographics (number of participants included in each study, age range, no of males and

females, and descriptive statistics), methods (aim of the study, intervention type, duration of participation),

and procedure (duration and frequency of treatment, and assessment tools used). This information along with

the study characteristics (such as author, year, and title) can be found in Table 1.

Quality Rating (With 5 being the highest)

Age range 3

no of males and females 4

descriptive statistics 5

Results

Study selection

The total number of references identified through database search is 529 and after duplicates were

removed, 331 studies were screened against the eligibility criteria. Studies were excluded initially based on

title, and subsequently some full text studies were also excluded. Factors determining the exclusion of

studies are related to reasons such as the target sample was not autistic population, and the intervention was

not targeting anxiety or depression, but rather cognitive systems or motor skills. Studies that targeted social

functioning and social skills were included. The final sample included 14 studies – 4 studies were Animal-

Assisted Intervention, 1 study was a Dance-Movement intervention, 4 studies were PEERS intervention, and

5 studies were MBT intervention. The PRISMA flowchart (Moher et al., 2009; Liberati et al., 2009) of the

systematic search results and the included studies is presented in Fig 1.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Fig 1. Flow diagram of included studies

Participant’s demographics and assessment tools

Across the 14 studies, the total number of participants was 454 - 74 were children (age range: 3 to 15

years), 146 were adolescents and young adults (age range: 11 to 28 years), 109 adults (age range: 20 to 65

years), and 3 studies combined adolescents, young adults and adults to a total number of 125 participants

(age range: 18+ to 65 years). Out of the total number, 314 participants were male and 140 females.

Measurements and assessment tools differed to some extend from intervention to intervention. As such,

in the identified and included studies, the most used assessment tools across studies were the Social

Responsiveness Scale (SRS - 7 studies) and Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA - 4

studies). Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), Social Skills Rating

System (SSRS), Empathy Quotient (EQ), Quality of Socialization Questionnaire (QSQ), Test of Young

Adult Social Skills Knowledge (TYASSK), The Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ), and the Dutch

Global Mood Scale (GMS) were each used in 3 different studies. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Kaufman

Brief Intelligence Test: Second Edition (KBIT-2), and Vineland-II each used in two different studies. The

remaining measures are Sensory Profile (SP), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Timberlawn Parent-

Child Interaction Scale, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (OLES-Q), Treatment

Satisfaction Survey (TSS), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), Heidelberger State Inventory (HIS),

Questionnaire of Movement Therapy (FBT), Emotional Empathy Scale (EES), Social Skills Inventory (SSI),

The Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ), Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge-Revised (TASSK-R),

Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), verbal comprehension index scale (WAIS-III), Mindful Attention and

Awareness Scale–Adolescent (MAAS-A), Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ), Ruminative Response

Scale (RRS), World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory

(FMI), The Parenting Stress Scale (PSS), Family Quality of Life (FQOL), The Child Behaviour Checklist

(CBCL), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). These measures were scarcely used across

studies.

The list of these assessment tools is presented underneath:

1. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS - 7 studies): To measure measure of autism symptoms.

2. Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA - 4 studies): To measure Emotional

Loneliness considering scaling as a tool.

3. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R): Evaluating different psychological problems along

with the symptoms of psychopathology.

4. Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Used for self diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders.

5. Social Skills Rating System (SSRS): To gather information in relation with much more complete

pictures of social behaviours from parents, teachers, along with students themselves dealing with

Autism.

Participant’s demographics and assessment tools

Across the 14 studies, the total number of participants was 454 - 74 were children (age range: 3 to 15

years), 146 were adolescents and young adults (age range: 11 to 28 years), 109 adults (age range: 20 to 65

years), and 3 studies combined adolescents, young adults and adults to a total number of 125 participants

(age range: 18+ to 65 years). Out of the total number, 314 participants were male and 140 females.

Measurements and assessment tools differed to some extend from intervention to intervention. As such,

in the identified and included studies, the most used assessment tools across studies were the Social

Responsiveness Scale (SRS - 7 studies) and Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA - 4

studies). Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), Social Skills Rating

System (SSRS), Empathy Quotient (EQ), Quality of Socialization Questionnaire (QSQ), Test of Young

Adult Social Skills Knowledge (TYASSK), The Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ), and the Dutch

Global Mood Scale (GMS) were each used in 3 different studies. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Kaufman

Brief Intelligence Test: Second Edition (KBIT-2), and Vineland-II each used in two different studies. The

remaining measures are Sensory Profile (SP), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Timberlawn Parent-

Child Interaction Scale, Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (OLES-Q), Treatment

Satisfaction Survey (TSS), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), Heidelberger State Inventory (HIS),

Questionnaire of Movement Therapy (FBT), Emotional Empathy Scale (EES), Social Skills Inventory (SSI),

The Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ), Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge-Revised (TASSK-R),

Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), verbal comprehension index scale (WAIS-III), Mindful Attention and

Awareness Scale–Adolescent (MAAS-A), Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ), Ruminative Response

Scale (RRS), World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory

(FMI), The Parenting Stress Scale (PSS), Family Quality of Life (FQOL), The Child Behaviour Checklist

(CBCL), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). These measures were scarcely used across

studies.

The list of these assessment tools is presented underneath:

1. Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS - 7 studies): To measure measure of autism symptoms.

2. Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA - 4 studies): To measure Emotional

Loneliness considering scaling as a tool.

3. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R): Evaluating different psychological problems along

with the symptoms of psychopathology.

4. Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Used for self diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders.

5. Social Skills Rating System (SSRS): To gather information in relation with much more complete

pictures of social behaviours from parents, teachers, along with students themselves dealing with

Autism.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6. Empathy Quotient (EQ): To measure empathy in adults.

7. Quality of Socialization Questionnaire (QSQ): To assess occupational stress and quality of working

life (QWL).

8. Test of Young Adult Social Skills Knowledge (TYASSK): To identify teen's knowledge in relation

with particular social skills taught during the intervention.

9. The Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ): To conduct personality test in much effective and

efficient manner.

10. The Dutch Global Mood Scale (GMS): It helps in analysing the measures that directly stays linked

with negative affect linking with malaise and fatigue. Also, it helps in analysing the positive effects

that are specifically being characterised by sociability and energy, in individuals with CHD.

11. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): This type of scaling aid in measuring the different levels through

which a respondents may not consider her/his life like if it is stressful. Also, it is specifically being

designed to analyse the different unpredictable situations & control an individual's life through

appraising.

12. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test: Second Edition (KBIT-2): It is designed to perform proper

screening considering the non-verbal and verbal skills or individual's ability (considering the age

from 4–90 years).

13. Vineland-II: This particular assessment tool is used for specifying impairment of behaviors that are

important for communication, socialization, along with daily functioning as well.

14. Sensory Profile (SP): Another crucial assessment tool, which helps in measuring the overall ability

of an individual. Basically, this aid in processing the overall sensory data and shows all the effects

on sensory processing of daily life activities.

15. Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): This is considered to be an effective tool that shows and

utilised to identify children aged 2 years and older with autism. The CARS was designed to help

differentiate children with autism from those with other developmental delays, such as intellectual

disability.

16. Timberlawn Parent-Child Interaction Scale: This type of scaling helps in improving the overall

conditions that may include stress, anxiety, asthma, and so on.

17. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (OLES-Q): This type of measurement

helps in focusing on different properties like quality of life considering the clinical settings.

18. Treatment Satisfaction Survey (TSS): This helps in assessing different patients dealing with

problems and aid in performing the treatment in rightful manner in order to satisfy them in much

effective and efficient manner.

19. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES): This is specifically considered as an effective programme

that helps in measuring the self-esteem for adult populations in much effective and in efficient

manner.

7. Quality of Socialization Questionnaire (QSQ): To assess occupational stress and quality of working

life (QWL).

8. Test of Young Adult Social Skills Knowledge (TYASSK): To identify teen's knowledge in relation

with particular social skills taught during the intervention.

9. The Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ): To conduct personality test in much effective and

efficient manner.

10. The Dutch Global Mood Scale (GMS): It helps in analysing the measures that directly stays linked

with negative affect linking with malaise and fatigue. Also, it helps in analysing the positive effects

that are specifically being characterised by sociability and energy, in individuals with CHD.

11. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): This type of scaling aid in measuring the different levels through

which a respondents may not consider her/his life like if it is stressful. Also, it is specifically being

designed to analyse the different unpredictable situations & control an individual's life through

appraising.

12. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test: Second Edition (KBIT-2): It is designed to perform proper

screening considering the non-verbal and verbal skills or individual's ability (considering the age

from 4–90 years).

13. Vineland-II: This particular assessment tool is used for specifying impairment of behaviors that are

important for communication, socialization, along with daily functioning as well.

14. Sensory Profile (SP): Another crucial assessment tool, which helps in measuring the overall ability

of an individual. Basically, this aid in processing the overall sensory data and shows all the effects

on sensory processing of daily life activities.

15. Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): This is considered to be an effective tool that shows and

utilised to identify children aged 2 years and older with autism. The CARS was designed to help

differentiate children with autism from those with other developmental delays, such as intellectual

disability.

16. Timberlawn Parent-Child Interaction Scale: This type of scaling helps in improving the overall

conditions that may include stress, anxiety, asthma, and so on.

17. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (OLES-Q): This type of measurement

helps in focusing on different properties like quality of life considering the clinical settings.

18. Treatment Satisfaction Survey (TSS): This helps in assessing different patients dealing with

problems and aid in performing the treatment in rightful manner in order to satisfy them in much

effective and efficient manner.

19. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES): This is specifically considered as an effective programme

that helps in measuring the self-esteem for adult populations in much effective and in efficient

manner.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

20. Heidelberger State Inventory (HIS): Another crucial type of assessment tool that aid in measuring

different properties like quality of life considering the clinical settings.

21. Questionnaire of Movement Therapy (FBT): Using a form of dance for the treatment of health-

related psychological problems.

22. Emotional Empathy Scale (EES): It is used to specifically focus among different emotional and

other types of components that are linking with empathy. A few dimensions that came in front are:

Positive Sharing, Empathic Suffering, Emotional Attention, Responsive Crying, Emotional

Contagion and Feeling for Others.

23. Social Skills Inventory (SSI): This specifically focuses on designing the measures over possession

of basic emotional and social communication skills.

24. The Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ): This type of assessment helps in measuring the quality of

last play date and the frequency of play dates. The administration of the QPQ begins by defining a

play date as a one-on-one experience.

25. Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge-Revised (TASSK-R): This is being considered to be an

effective assessment tool, which helps in assessing the knowledge of teens who are dealing with

autism about different social skills.

26. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): This specific assessment tool is utilised to reduce the severity of

social anxiety disorder faced by individuals dealing with autism.

27. Verbal comprehension index scale (WAIS-III): This type of index helps in measuring the overall

retrieval considering the long term memory of data which flows in an individual’s mind-set.

28. Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale–Adolescent (MAAS-A): Another crucial assessment tool

that focuses on enhancing and measuring the overall mindfulness among adolescents and children.

29. Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ): This assessment tool focuses on identifying the worries

more than depression and anxiety.

30. Ruminative Response Scale (RRS): This type of scale helps in measuring the different range of

responses given by an individual in relation with depression, reflection and brooding as well.

31. World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5): This helps in focusing on primary

healthcare given by health care providers to citizens of Europe.

32. Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI): This type of approach is utilised validating the information

considering the reliable questionnaire and it also helps in measuring mindfulness of individuals

dealing with autism or any other problem as well which are linking to mental health.

33. The Parenting Stress Scale (PSS): This helps in focusing on different aspects like stress while

considering different elements like joys & demands of parenting.

34. Family Quality of Life (FQOL): Family related satisfaction is something on which this type of

assessment tool is focused.

35. The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL): Particularly, this type of assessment is utilised considering

questionnaire to assess emotional and behavioural issues. Including this, it is said that this tool often

different properties like quality of life considering the clinical settings.

21. Questionnaire of Movement Therapy (FBT): Using a form of dance for the treatment of health-

related psychological problems.

22. Emotional Empathy Scale (EES): It is used to specifically focus among different emotional and

other types of components that are linking with empathy. A few dimensions that came in front are:

Positive Sharing, Empathic Suffering, Emotional Attention, Responsive Crying, Emotional

Contagion and Feeling for Others.

23. Social Skills Inventory (SSI): This specifically focuses on designing the measures over possession

of basic emotional and social communication skills.

24. The Quality of Play Questionnaire (QPQ): This type of assessment helps in measuring the quality of

last play date and the frequency of play dates. The administration of the QPQ begins by defining a

play date as a one-on-one experience.

25. Test of Adolescent Social Skills Knowledge-Revised (TASSK-R): This is being considered to be an

effective assessment tool, which helps in assessing the knowledge of teens who are dealing with

autism about different social skills.

26. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): This specific assessment tool is utilised to reduce the severity of

social anxiety disorder faced by individuals dealing with autism.

27. Verbal comprehension index scale (WAIS-III): This type of index helps in measuring the overall

retrieval considering the long term memory of data which flows in an individual’s mind-set.

28. Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale–Adolescent (MAAS-A): Another crucial assessment tool

that focuses on enhancing and measuring the overall mindfulness among adolescents and children.

29. Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ): This assessment tool focuses on identifying the worries

more than depression and anxiety.

30. Ruminative Response Scale (RRS): This type of scale helps in measuring the different range of

responses given by an individual in relation with depression, reflection and brooding as well.

31. World Health Organization–Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5): This helps in focusing on primary

healthcare given by health care providers to citizens of Europe.

32. Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI): This type of approach is utilised validating the information

considering the reliable questionnaire and it also helps in measuring mindfulness of individuals

dealing with autism or any other problem as well which are linking to mental health.

33. The Parenting Stress Scale (PSS): This helps in focusing on different aspects like stress while

considering different elements like joys & demands of parenting.

34. Family Quality of Life (FQOL): Family related satisfaction is something on which this type of

assessment tool is focused.

35. The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL): Particularly, this type of assessment is utilised considering

questionnaire to assess emotional and behavioural issues. Including this, it is said that this tool often

helps collecting information in relation with diagnostic screener. However, ASD are specifically not

being included under this type of checklist related tests.

36. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): This type of assessment tool is used for analysing

the different mood disorders of individuals who are going through mental issues like depression,

anxiety and so on

being included under this type of checklist related tests.

36. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): This type of assessment tool is used for analysing

the different mood disorders of individuals who are going through mental issues like depression,

anxiety and so on

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 34

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.