Comprehensive Analysis of Money Market, Eurocurrency, and Fed Funds

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/26

|15

|5514

|167

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a detailed analysis of the money market, Eurocurrency market, and related financial instruments. It explores the functions of the money market in transferring funds, distinguishing between the capital and money markets, and outlining the key participants including commercial banks, governments, and the Federal Reserve. The report defines the Eurocurrency market, discussing its origins, features, and the dominance of the Eurodollar market. It also delves into the factors contributing to the growth of the Eurodollar market, including the Cold War, balance of payments deficits, and regulatory factors like Regulation Q. Furthermore, the report examines specific instruments such as Fed Funds, repurchase agreements, and the discount rate, explaining their roles and importance in the money market. The report also touches upon Nostro and Vostro accounts in the context of international financial transactions.

THE MONEY MARKET

Functions of the Money Market

The purpose of the money market is to transfer funds from lenders to borrowers. A common

distinction made by money market participants is between the “Capital Market and the “Money

Market”, with the latter term generally referring to borrowing and lending for periods of a year

or less.

The money market encompasses a group of short term credit market instruments, futures market

instruments and the Federal Reserve discount window. The major participants in the money

market are commercial banks, government, brokers and dealers and the Federal Reserve.

THE EUROCURRENCY MARKET

What is the Eurocurrency Market?

Definition:

A Eurocurrency is a currency which is available for deposit or loan in a country which is not the

domestic currency. As such, it can be virtually any currency which is not subject to stringent

control in its domestic location and is not limited to only European currencies. Then why “Euro”

in the name? This was because the market for the depositing and lending of such funds first

started in Europe in the 50’s and early 60’s.

The definition given above embraces all currencies for “Euro” purposes but such is the

omnipotence of the US$ that the market itself s often referred to as the Eurodollar market. The

major currencies and to a certain extent in varying degrees other currencies such as Saudi Riyals

and S$ are also found suitable. In fact, ignoring Exchange Controls, any convertible currency if it

is backed by a swap market can exist in Euro form.

The Eurocurrency market is essentially a deposit market and there is no buying or selling of

currencies. The period of time for the deposits most commonly range from call to 6 months

although some business is concluded on periods up to 10 yea

Profile of the Eurocurrency Market

Historically, the Eurocurrency market started with the Eurodollar market. After World War 2, the

communist countries in Europe found themselves with foreign exchange reserves denominated

largely in US$. The natural way to hold these reserves would have been to keep them in bank

deposits and other securities in the United States. However, due to the cold war which existed

after the war, the danger that the United States might expropriate or otherwise control these !)

Functions of the Money Market

The purpose of the money market is to transfer funds from lenders to borrowers. A common

distinction made by money market participants is between the “Capital Market and the “Money

Market”, with the latter term generally referring to borrowing and lending for periods of a year

or less.

The money market encompasses a group of short term credit market instruments, futures market

instruments and the Federal Reserve discount window. The major participants in the money

market are commercial banks, government, brokers and dealers and the Federal Reserve.

THE EUROCURRENCY MARKET

What is the Eurocurrency Market?

Definition:

A Eurocurrency is a currency which is available for deposit or loan in a country which is not the

domestic currency. As such, it can be virtually any currency which is not subject to stringent

control in its domestic location and is not limited to only European currencies. Then why “Euro”

in the name? This was because the market for the depositing and lending of such funds first

started in Europe in the 50’s and early 60’s.

The definition given above embraces all currencies for “Euro” purposes but such is the

omnipotence of the US$ that the market itself s often referred to as the Eurodollar market. The

major currencies and to a certain extent in varying degrees other currencies such as Saudi Riyals

and S$ are also found suitable. In fact, ignoring Exchange Controls, any convertible currency if it

is backed by a swap market can exist in Euro form.

The Eurocurrency market is essentially a deposit market and there is no buying or selling of

currencies. The period of time for the deposits most commonly range from call to 6 months

although some business is concluded on periods up to 10 yea

Profile of the Eurocurrency Market

Historically, the Eurocurrency market started with the Eurodollar market. After World War 2, the

communist countries in Europe found themselves with foreign exchange reserves denominated

largely in US$. The natural way to hold these reserves would have been to keep them in bank

deposits and other securities in the United States. However, due to the cold war which existed

after the war, the danger that the United States might expropriate or otherwise control these !)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

reserves became unacceptable to these communist countries. As an alternative, these countries

began placing their deposits in banks outside the United States, often in London. The deposit

were still denominated largely in US$, however the immediate legal iabilities fell outside the

United States. The sharp rise of crude oil prices in the early 1970’s led to vast accumulation of

dollar reserves (later known as petro-dollars) which further accentuated the growth of this

market.

Market Features:

1) Must be unregulated – there must be complete freedom in the flow of funds to and from the

market, that is, no central bank, government bodies or international bodies in any of the

participating countries to control the flow of the market ( although in recent times because of the

terrorist scourge some form of controls were implemented to stem the flow of funds to these

groups).

2) No reserve requirement against Eurodeposits

3) The Eurodeposit is an external currency deposit in the country it is located, hence the term

“Offshore Banking” to refer to such funding activities.

4) Wholesale market – it is predominantly an interbank market. Amounts normally range from

US$1 million upwards- although sizes of 0.5 million or less may be dealt.

5) Primarily short-term – Overnight to 1 year most readily quoted. There is a very thin market for 1

to

5 years and hardly anything beyond 5 years.

6) Eurocurrency interest rates are typically higher than the domestic interest rates because there is

no reserve requirement.

All transactions are done on an unsecured basis without collateral or securities.

EURO-DOLLAR MARKET

Factors contributing to the Growth of the Eurodollar Market

While the cold war may have kicked off the Euromarket, there were other factors that stimulated

its development. Historically, the GBP played a key role in world trade. A great deal of trade not

only within the British Commonwealth nations and the rest of the world or between non-

commonwealth countries was denominated in GBP and financed in London through borrowing of

GBP. After World War 2, this began to change as the UK ran began to run big balance of payment

deficits and as a result led to the devaluation of the GBP.The chronic weakness of the GBP made

it a less attractive currency to earn and to hold which inturn stimulated the trend for more and more

international trade to be denominated in US$.

began placing their deposits in banks outside the United States, often in London. The deposit

were still denominated largely in US$, however the immediate legal iabilities fell outside the

United States. The sharp rise of crude oil prices in the early 1970’s led to vast accumulation of

dollar reserves (later known as petro-dollars) which further accentuated the growth of this

market.

Market Features:

1) Must be unregulated – there must be complete freedom in the flow of funds to and from the

market, that is, no central bank, government bodies or international bodies in any of the

participating countries to control the flow of the market ( although in recent times because of the

terrorist scourge some form of controls were implemented to stem the flow of funds to these

groups).

2) No reserve requirement against Eurodeposits

3) The Eurodeposit is an external currency deposit in the country it is located, hence the term

“Offshore Banking” to refer to such funding activities.

4) Wholesale market – it is predominantly an interbank market. Amounts normally range from

US$1 million upwards- although sizes of 0.5 million or less may be dealt.

5) Primarily short-term – Overnight to 1 year most readily quoted. There is a very thin market for 1

to

5 years and hardly anything beyond 5 years.

6) Eurocurrency interest rates are typically higher than the domestic interest rates because there is

no reserve requirement.

All transactions are done on an unsecured basis without collateral or securities.

EURO-DOLLAR MARKET

Factors contributing to the Growth of the Eurodollar Market

While the cold war may have kicked off the Euromarket, there were other factors that stimulated

its development. Historically, the GBP played a key role in world trade. A great deal of trade not

only within the British Commonwealth nations and the rest of the world or between non-

commonwealth countries was denominated in GBP and financed in London through borrowing of

GBP. After World War 2, this began to change as the UK ran began to run big balance of payment

deficits and as a result led to the devaluation of the GBP.The chronic weakness of the GBP made

it a less attractive currency to earn and to hold which inturn stimulated the trend for more and more

international trade to be denominated in US$.

During the early 1950’s when the Russian and East European banks began depositing US$ outside

The United States, the London branches of U.S banks were not taking Eurodollar deposits. They

began to do. So very reluctantly several years later when some of their good US customers said to

them “Cant’t you Take our deposits in London?. The foreign banks do and they give u better rates

than you can in New York Because of Regulation Q- the imposition of maximum interest rates on

certain categories of deposits offered By domicile American banks. For several years this worked

out satisfactorily because the head offices of the US banks involved could use the dollars deposited

with their London branches in the U.S; this was so because the structure of loan and other interest

rates in the U.S was such that US banks could well afford to pay higher rates than those permitted

under Regulation Q.

A third factor that stimulated the growth of the Euromarket was the operation of Regulation Q

during the tight money years of 1968 and 1969. At that time, US money market rates rose above

the rates that banks were permitted to pay under RegulationQ on domestic large denominated

CD’s. In order to finance loans US banks were force to borrow money in the Euromarket. The

operation of Regulation Q also encouraged foreign holders of dollars who would have deposited

them in New York to put them in London.

The persistent balance of payments deficits in the U.S have often been given substantial credit for

the development of the Euromarket. By spending more abroad than it earned, the U.S. in effect put

dollars into the hands of foreigners and thus created a natural supply of dollars in the Euromarket.

What has made the Euromarket attractive to depositors and given it much of its vitality is the

freedom from restrictions under which this market operates, in particular the absence of the

implicit tax that exists on US domestic bankingactivities because of the reserve requirements

imposed by the Fed.

Petro-Dollars

Major Eurocurrency Centres

A) Europe – London, Paris, Zurich and Frankfurt

B) Asia – Singapore, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Australia.

C) Middle East – Bahrain

D) Western Hemisphere – Nassau and Grand Cayman

Fed Funds and Clearing House Funds:

Federal Funds or Fed Funds as they are commonly called are funds held in a bank’s reserve

account at its local Federal Reserve Bank. There are 12 Federal Reserve Banks each for one of the

12 Federal Resrve districts which the U.S is divided into. Thus all banks that are members of the

Federal Reserve System are required to keep minimum reserves at their respective Federal Reserve

Bank. A commercial bank’s reserve account is much like a consumers checking account; the bank

makes deposit into it and can transfer funds out of it.The main difference is that while a consumer

can run the balance in his checking account down to zero, each member bank is required to

The United States, the London branches of U.S banks were not taking Eurodollar deposits. They

began to do. So very reluctantly several years later when some of their good US customers said to

them “Cant’t you Take our deposits in London?. The foreign banks do and they give u better rates

than you can in New York Because of Regulation Q- the imposition of maximum interest rates on

certain categories of deposits offered By domicile American banks. For several years this worked

out satisfactorily because the head offices of the US banks involved could use the dollars deposited

with their London branches in the U.S; this was so because the structure of loan and other interest

rates in the U.S was such that US banks could well afford to pay higher rates than those permitted

under Regulation Q.

A third factor that stimulated the growth of the Euromarket was the operation of Regulation Q

during the tight money years of 1968 and 1969. At that time, US money market rates rose above

the rates that banks were permitted to pay under RegulationQ on domestic large denominated

CD’s. In order to finance loans US banks were force to borrow money in the Euromarket. The

operation of Regulation Q also encouraged foreign holders of dollars who would have deposited

them in New York to put them in London.

The persistent balance of payments deficits in the U.S have often been given substantial credit for

the development of the Euromarket. By spending more abroad than it earned, the U.S. in effect put

dollars into the hands of foreigners and thus created a natural supply of dollars in the Euromarket.

What has made the Euromarket attractive to depositors and given it much of its vitality is the

freedom from restrictions under which this market operates, in particular the absence of the

implicit tax that exists on US domestic bankingactivities because of the reserve requirements

imposed by the Fed.

Petro-Dollars

Major Eurocurrency Centres

A) Europe – London, Paris, Zurich and Frankfurt

B) Asia – Singapore, Hong Kong, Tokyo and Australia.

C) Middle East – Bahrain

D) Western Hemisphere – Nassau and Grand Cayman

Fed Funds and Clearing House Funds:

Federal Funds or Fed Funds as they are commonly called are funds held in a bank’s reserve

account at its local Federal Reserve Bank. There are 12 Federal Reserve Banks each for one of the

12 Federal Resrve districts which the U.S is divided into. Thus all banks that are members of the

Federal Reserve System are required to keep minimum reserves at their respective Federal Reserve

Bank. A commercial bank’s reserve account is much like a consumers checking account; the bank

makes deposit into it and can transfer funds out of it.The main difference is that while a consumer

can run the balance in his checking account down to zero, each member bank is required to

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

maintain some minimum average balance in its reserve account and that minimum balance

depends on the size of the previous weeks. Hence any increase in bank deposits entail the supply

of Fed Funds, while loans made and securities purchased reduce that supply. Thus the basic

amount of money any bank can lent out and otherwise invest equals the amount of funds it has

received from depositors minus the reserves it is required to maintain.

For some banks, this supply of available funds roughly equals the amount they choose to invest in

securities plus that demanded from them by borrowers. But this may not be the case for most

banks. In reality, because the nations largest corporations tend to concentrate their borrowing in

big money centre banks in New York and other major financial centres, the loans and investments

these banks have to fund exceed the deposits they receive. In contrast, many smaller banks receive

more money from local depositors that they lend locally or choose to invest. Many of these smaller

regional banks have excess funds at the Federal and therefore are able to lend to big money centre

banks.

The borrowing is done in the Fed Funds Market. Most of the Fed Funds loans are for overnight

transaction.Some of these transactions are made directly between banks while others are done

through money brokers in the big money centres. Lending of Feds is usually referred to as sale

while borrowing of Feds is usually referred to as purchase. Longer period transactions are referred

to as term Fed Funds.

-3-

The importance of the Fed Funds Market

The rate of interest paid on overnight loans of Fed Funds (Fed Funds rate) is the key interest rate in

the money market and all other short-term rates are influenced by it. Without doubt this market has

grown to become one of the most important market in the U.S. and is watched very closely by the

rest of the financial markets globally.

The importance of this single day rate stems from the fact that it gives a clue to the rest of the

world’s financial community to the monetary inclinations of the Federal Reserve. This rate is

highly sensitive to the Federal Reserve actions through its control and provision of reserves of

member banks in the U.S. The level of Fed Funds rate influences the yields and as such the overall

return on investment and likewise the cost of money.

Repurchase Agreement or Repos

Apart from the Fed Funds market which is mainly an overnight market, banks or securities dealers

needing funds or having excess funds for a slightly longer period can turn to the repo market. A

repo agreement is the sale of securities under an agreement to repurchase it back at a later date

(normally a few days). Effectively, this is borrowing using the securities as a collateral. It is free of

reserve requirements.

Discount Rate ( lender of last resort)

depends on the size of the previous weeks. Hence any increase in bank deposits entail the supply

of Fed Funds, while loans made and securities purchased reduce that supply. Thus the basic

amount of money any bank can lent out and otherwise invest equals the amount of funds it has

received from depositors minus the reserves it is required to maintain.

For some banks, this supply of available funds roughly equals the amount they choose to invest in

securities plus that demanded from them by borrowers. But this may not be the case for most

banks. In reality, because the nations largest corporations tend to concentrate their borrowing in

big money centre banks in New York and other major financial centres, the loans and investments

these banks have to fund exceed the deposits they receive. In contrast, many smaller banks receive

more money from local depositors that they lend locally or choose to invest. Many of these smaller

regional banks have excess funds at the Federal and therefore are able to lend to big money centre

banks.

The borrowing is done in the Fed Funds Market. Most of the Fed Funds loans are for overnight

transaction.Some of these transactions are made directly between banks while others are done

through money brokers in the big money centres. Lending of Feds is usually referred to as sale

while borrowing of Feds is usually referred to as purchase. Longer period transactions are referred

to as term Fed Funds.

-3-

The importance of the Fed Funds Market

The rate of interest paid on overnight loans of Fed Funds (Fed Funds rate) is the key interest rate in

the money market and all other short-term rates are influenced by it. Without doubt this market has

grown to become one of the most important market in the U.S. and is watched very closely by the

rest of the financial markets globally.

The importance of this single day rate stems from the fact that it gives a clue to the rest of the

world’s financial community to the monetary inclinations of the Federal Reserve. This rate is

highly sensitive to the Federal Reserve actions through its control and provision of reserves of

member banks in the U.S. The level of Fed Funds rate influences the yields and as such the overall

return on investment and likewise the cost of money.

Repurchase Agreement or Repos

Apart from the Fed Funds market which is mainly an overnight market, banks or securities dealers

needing funds or having excess funds for a slightly longer period can turn to the repo market. A

repo agreement is the sale of securities under an agreement to repurchase it back at a later date

(normally a few days). Effectively, this is borrowing using the securities as a collateral. It is free of

reserve requirements.

Discount Rate ( lender of last resort)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The oldest instrument of central banking is what is called the “Bank Rate “ in the UK and the

discount rate of the Federal Reserve Banks in the U.S. The discount rate charged to would-be

borrowers (commercial banks) dictates all other key interest rates such as prime rates. However,

care should be taken to generalize the above statement as the traditional view of the importance of

the discount rate has changed in recent years. Open market operations are now seen as the most

powerful and flexible monetary tool of the Fed.

Nostro and Vostro Accounts

For money market and foreign exchange operations which involves sizeable foreign currency

funds flow, banks maintain an intricate network of accounts and counteraccounts among different

banks all over the world. A local bank in Singapore or a German Bank in Frankfurt have to

maintain a US dollar a/c with a bank in New York for purposes of making a US$ payment or

receiving US$ receipts. Likewise a US bank need to have a EURO account with an ECB bank or a

Singapore dollar account with a local bank for payment and receiving EURO’s ans S$

respectively.

Such accounts are referred to as due from (nostro) and due to (vostro)accounts. A nostro is a

foreign currency account of a bank maintained with its foreign correspondents abroad. In the above

example the local bank in Singapore and and German bank in Frankfurt each have their respective

US$ nostro accounts with their respective US banks in New York. The respective US banks in

return regard the Singapore and German bank’s account with them as vostro as they are account

due.

Take an example if Deutsche Bank Singapore maintains its US$ account with Citibank New York

and Malaysian Ringgit account with Bank Bumiputra Kuala Lumpur. If a dealer in Deutsche Bank

asked “What’s our balance in our nostros in New York and Kuala Lumpur”? – he is in fact asking

what Deutsche have in balances in US$ and Malaysian Ringgit in their respective account in

Citibank New York and Bank Bumiputra Kuala Lumpur..

Money Market Instruments

There are basically two types of instruments issued and traded in the money market,

namely:

Instruments which pay interest on the amount invested, where the interest is

normally paid to the holder of the instrument (the lender), together with the

redemption amount at redemption date. Interim interest payments may be made

in certain cases. These instruments are called interest instruments. Instruments in

this category include:

discount rate of the Federal Reserve Banks in the U.S. The discount rate charged to would-be

borrowers (commercial banks) dictates all other key interest rates such as prime rates. However,

care should be taken to generalize the above statement as the traditional view of the importance of

the discount rate has changed in recent years. Open market operations are now seen as the most

powerful and flexible monetary tool of the Fed.

Nostro and Vostro Accounts

For money market and foreign exchange operations which involves sizeable foreign currency

funds flow, banks maintain an intricate network of accounts and counteraccounts among different

banks all over the world. A local bank in Singapore or a German Bank in Frankfurt have to

maintain a US dollar a/c with a bank in New York for purposes of making a US$ payment or

receiving US$ receipts. Likewise a US bank need to have a EURO account with an ECB bank or a

Singapore dollar account with a local bank for payment and receiving EURO’s ans S$

respectively.

Such accounts are referred to as due from (nostro) and due to (vostro)accounts. A nostro is a

foreign currency account of a bank maintained with its foreign correspondents abroad. In the above

example the local bank in Singapore and and German bank in Frankfurt each have their respective

US$ nostro accounts with their respective US banks in New York. The respective US banks in

return regard the Singapore and German bank’s account with them as vostro as they are account

due.

Take an example if Deutsche Bank Singapore maintains its US$ account with Citibank New York

and Malaysian Ringgit account with Bank Bumiputra Kuala Lumpur. If a dealer in Deutsche Bank

asked “What’s our balance in our nostros in New York and Kuala Lumpur”? – he is in fact asking

what Deutsche have in balances in US$ and Malaysian Ringgit in their respective account in

Citibank New York and Bank Bumiputra Kuala Lumpur..

Money Market Instruments

There are basically two types of instruments issued and traded in the money market,

namely:

Instruments which pay interest on the amount invested, where the interest is

normally paid to the holder of the instrument (the lender), together with the

redemption amount at redemption date. Interim interest payments may be made

in certain cases. These instruments are called interest instruments. Instruments in

this category include:

Negotiable Certificate of Deposit (NCDs)

Interest rate instruments issued by the private sector, with terms to maturity of less than

three years.

Instruments that do not pay interest on the amount invested but are issued at a

discount on the nominal value (the redemption amount). These instruments are

called discount instruments. Instruments in this category include:

Bankers' Acceptances (BAs)

Treasury Bills (TBs)

Commercial Paper (CPs)

Negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs)

A negotiable certificate of deposit is a certificate issued by a bank for a deposit made at

the bank. This deposit attracts a fixed rate of interest, which is normally payable to the

holder of the instrument together with the nominal amount invested, at redemption date.

NCDs are normally issued in multiples of $1000 but more likely $100,000. The NCD

will contain the following information:

name of the issuing bank

date of issue

date of redemption (maturity date)

amount of the deposit

maturity value

annual interest rate paid on the deposit.

NCDs are bearer documents, which means that the name of the owner (holder or

depositor) does not appear on the document. The bearer or holder of the document will

receive the maturity value (the amount deposited plus interest) at maturity date.

Characteristics

Large denominations time deposit, less than six months maturity

Negotiable - may be sold and traded before maturity

Issued at face value with coupon rate

Purchased mainly by corporate businesses

Calculations:

The maturity value (MV) of an NCD will be the nominal amount deposited

Interest rate instruments issued by the private sector, with terms to maturity of less than

three years.

Instruments that do not pay interest on the amount invested but are issued at a

discount on the nominal value (the redemption amount). These instruments are

called discount instruments. Instruments in this category include:

Bankers' Acceptances (BAs)

Treasury Bills (TBs)

Commercial Paper (CPs)

Negotiable certificates of deposit (NCDs)

A negotiable certificate of deposit is a certificate issued by a bank for a deposit made at

the bank. This deposit attracts a fixed rate of interest, which is normally payable to the

holder of the instrument together with the nominal amount invested, at redemption date.

NCDs are normally issued in multiples of $1000 but more likely $100,000. The NCD

will contain the following information:

name of the issuing bank

date of issue

date of redemption (maturity date)

amount of the deposit

maturity value

annual interest rate paid on the deposit.

NCDs are bearer documents, which means that the name of the owner (holder or

depositor) does not appear on the document. The bearer or holder of the document will

receive the maturity value (the amount deposited plus interest) at maturity date.

Characteristics

Large denominations time deposit, less than six months maturity

Negotiable - may be sold and traded before maturity

Issued at face value with coupon rate

Purchased mainly by corporate businesses

Calculations:

The maturity value (MV) of an NCD will be the nominal amount deposited

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(N) plus the interest for the period. If for instance a deposit of $1 million is

made on 1 March for 90 days, and interest paid on the amount is 15%

(referred to as a 15% 90-day NCD), the maturity value is calculated as

follows:

Nominal amount $1 000 000

Interest for period (15% x $1 000 000 x 90/360) $ 37 500

MV $1 037 500

The general formula would be:

MV = N x (1 + (1 x c/100 x d/360)

where

MV = maturity value

N = nominal amount of the certificate (amount deposited)

c = interest paid on the amount deposited, as indicated on the certificate

(referred to as the coupon rate). This is expressed as a fixed amount

and not as a percentage, e.g. 15 and not 15%

d = period of the instrument in days referred to as the tenor

In this case

N = $1 000 000

c = 15

d = 90

MV = R1 037 500

If the holder sells this instrument to another party before the redemption date, the

proceeds can be calculated. Remember that financial instruments are traded between

parties on a yield to maturity (expressed as an interest rate) basis, because interest is the

price that is paid for money borrowed. The proceeds of the sale are calculated as follows:

Proceeds = MV / [1 + (d/360 x i/100)]

where

MV = maturity value

d = remaining tenor in days

i = yield at which the instrument was traded expressed as a fixed

amount

If, in the above example, the NCD is sold on 31 March at a yield of 14%, the proceeds to

the seller (the amount the buyer will pay) is:

made on 1 March for 90 days, and interest paid on the amount is 15%

(referred to as a 15% 90-day NCD), the maturity value is calculated as

follows:

Nominal amount $1 000 000

Interest for period (15% x $1 000 000 x 90/360) $ 37 500

MV $1 037 500

The general formula would be:

MV = N x (1 + (1 x c/100 x d/360)

where

MV = maturity value

N = nominal amount of the certificate (amount deposited)

c = interest paid on the amount deposited, as indicated on the certificate

(referred to as the coupon rate). This is expressed as a fixed amount

and not as a percentage, e.g. 15 and not 15%

d = period of the instrument in days referred to as the tenor

In this case

N = $1 000 000

c = 15

d = 90

MV = R1 037 500

If the holder sells this instrument to another party before the redemption date, the

proceeds can be calculated. Remember that financial instruments are traded between

parties on a yield to maturity (expressed as an interest rate) basis, because interest is the

price that is paid for money borrowed. The proceeds of the sale are calculated as follows:

Proceeds = MV / [1 + (d/360 x i/100)]

where

MV = maturity value

d = remaining tenor in days

i = yield at which the instrument was traded expressed as a fixed

amount

If, in the above example, the NCD is sold on 31 March at a yield of 14%, the proceeds to

the seller (the amount the buyer will pay) is:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Proceeds = $1 037 500 / [1 + (60/360 x 14/100)]

= $1 013 846 where

MV = $1 037 500

d = 60

i = 14

The buyer will be the new holder, and he may present the NCD to the bank on

redemption date to receive the maturity value of $1 037 500 or sell it in the secondary

market prior to maturity.

Bankers' acceptances

A bankers' acceptance was invented to suit the needs of a party requiring temporary

finance to facilitate the trading of specific goods. The party needing finance would

approach investors for this temporary finance. The investors or lenders would then lend a

certain amount to the borrower in exchange for a document stating that the debt would be

paid back on a certain date in the short-term future. For this arrangement to be attractive

to the lender, the amount paid back by the borrower (called the nominal amount) would

have to be more than the amount advanced by die lender. The difference between the

amount advanced and the amount paid back (the nominal amount) is known as the

discount on the nominal amount. The two parties would normally be brought together by

a bank.

The redemption of the loan would have to be guaranteed by a bank, called the acceptance

by the bank making the arrangement. Thus the name "bankers' acceptance".

The holder of the document may, at the redemption date approach the bank who will pay

the nominal amount to the holder. The bank will then claim the nominal amount from the

borrowers.

A bank acceptance can, in formal terms, be described as an unconditional order in writing

addressed and signed by a drawer (the lender)

to a bank which signs the document and becomes the acceptor

promising to pay a certain amount of money at a fixed date in the future

to the bearer or holder (the borrower) of the document (the acceptance).

Characteristics

Time draft - order to pay in future

= $1 013 846 where

MV = $1 037 500

d = 60

i = 14

The buyer will be the new holder, and he may present the NCD to the bank on

redemption date to receive the maturity value of $1 037 500 or sell it in the secondary

market prior to maturity.

Bankers' acceptances

A bankers' acceptance was invented to suit the needs of a party requiring temporary

finance to facilitate the trading of specific goods. The party needing finance would

approach investors for this temporary finance. The investors or lenders would then lend a

certain amount to the borrower in exchange for a document stating that the debt would be

paid back on a certain date in the short-term future. For this arrangement to be attractive

to the lender, the amount paid back by the borrower (called the nominal amount) would

have to be more than the amount advanced by die lender. The difference between the

amount advanced and the amount paid back (the nominal amount) is known as the

discount on the nominal amount. The two parties would normally be brought together by

a bank.

The redemption of the loan would have to be guaranteed by a bank, called the acceptance

by the bank making the arrangement. Thus the name "bankers' acceptance".

The holder of the document may, at the redemption date approach the bank who will pay

the nominal amount to the holder. The bank will then claim the nominal amount from the

borrowers.

A bank acceptance can, in formal terms, be described as an unconditional order in writing

addressed and signed by a drawer (the lender)

to a bank which signs the document and becomes the acceptor

promising to pay a certain amount of money at a fixed date in the future

to the bearer or holder (the borrower) of the document (the acceptance).

Characteristics

Time draft - order to pay in future

Direct liability of bank

Mostly trade related

Secondary market - dealer market

Discounted in market to reflect yield

Standard maturities of 30,60,90 and 180 days

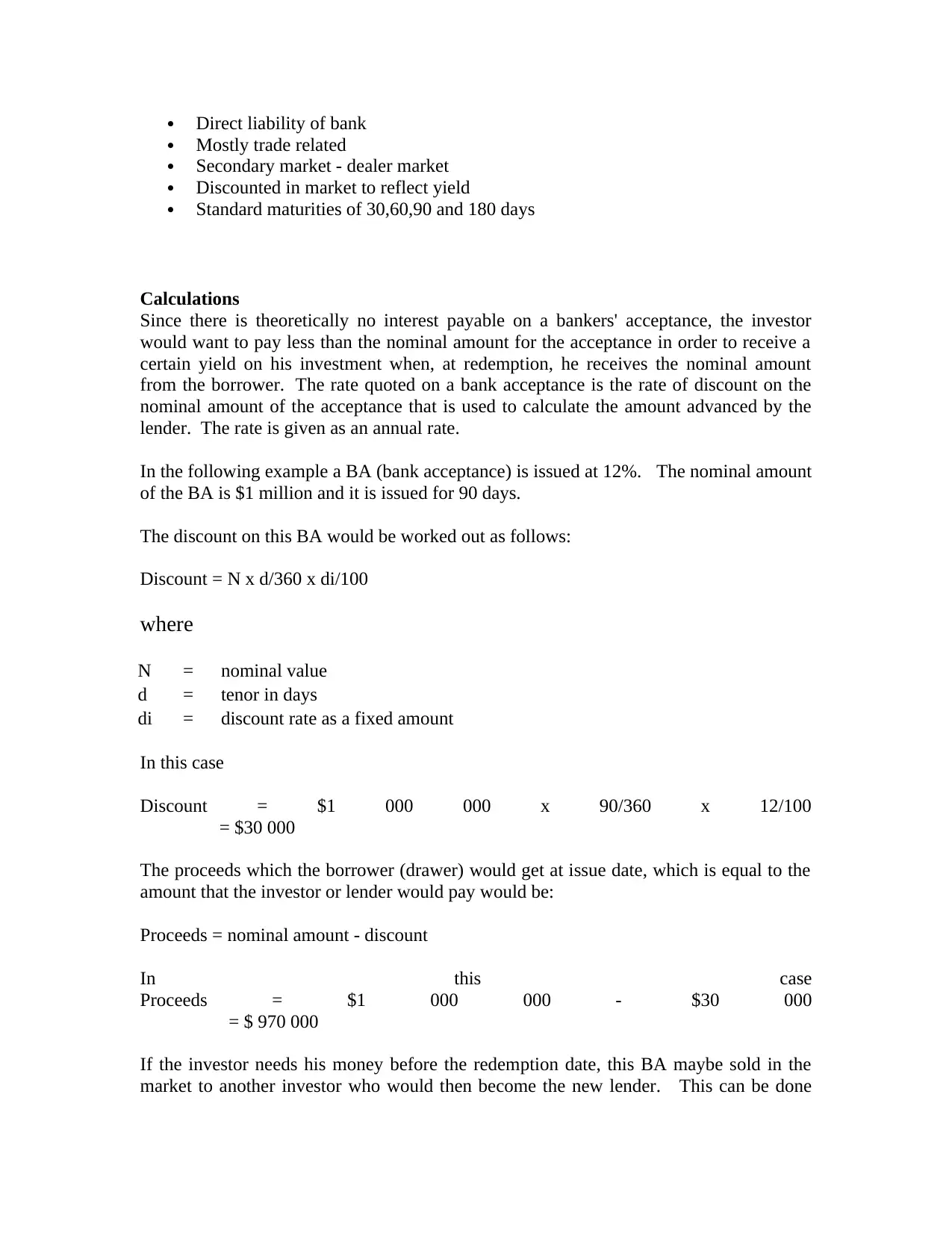

Calculations

Since there is theoretically no interest payable on a bankers' acceptance, the investor

would want to pay less than the nominal amount for the acceptance in order to receive a

certain yield on his investment when, at redemption, he receives the nominal amount

from the borrower. The rate quoted on a bank acceptance is the rate of discount on the

nominal amount of the acceptance that is used to calculate the amount advanced by the

lender. The rate is given as an annual rate.

In the following example a BA (bank acceptance) is issued at 12%. The nominal amount

of the BA is $1 million and it is issued for 90 days.

The discount on this BA would be worked out as follows:

Discount = N x d/360 x di/100

where

N = nominal value

d = tenor in days

di = discount rate as a fixed amount

In this case

Discount = $1 000 000 x 90/360 x 12/100

= $30 000

The proceeds which the borrower (drawer) would get at issue date, which is equal to the

amount that the investor or lender would pay would be:

Proceeds = nominal amount - discount

In this case

Proceeds = $1 000 000 - $30 000

= $ 970 000

If the investor needs his money before the redemption date, this BA maybe sold in the

market to another investor who would then become the new lender. This can be done

Mostly trade related

Secondary market - dealer market

Discounted in market to reflect yield

Standard maturities of 30,60,90 and 180 days

Calculations

Since there is theoretically no interest payable on a bankers' acceptance, the investor

would want to pay less than the nominal amount for the acceptance in order to receive a

certain yield on his investment when, at redemption, he receives the nominal amount

from the borrower. The rate quoted on a bank acceptance is the rate of discount on the

nominal amount of the acceptance that is used to calculate the amount advanced by the

lender. The rate is given as an annual rate.

In the following example a BA (bank acceptance) is issued at 12%. The nominal amount

of the BA is $1 million and it is issued for 90 days.

The discount on this BA would be worked out as follows:

Discount = N x d/360 x di/100

where

N = nominal value

d = tenor in days

di = discount rate as a fixed amount

In this case

Discount = $1 000 000 x 90/360 x 12/100

= $30 000

The proceeds which the borrower (drawer) would get at issue date, which is equal to the

amount that the investor or lender would pay would be:

Proceeds = nominal amount - discount

In this case

Proceeds = $1 000 000 - $30 000

= $ 970 000

If the investor needs his money before the redemption date, this BA maybe sold in the

market to another investor who would then become the new lender. This can be done

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

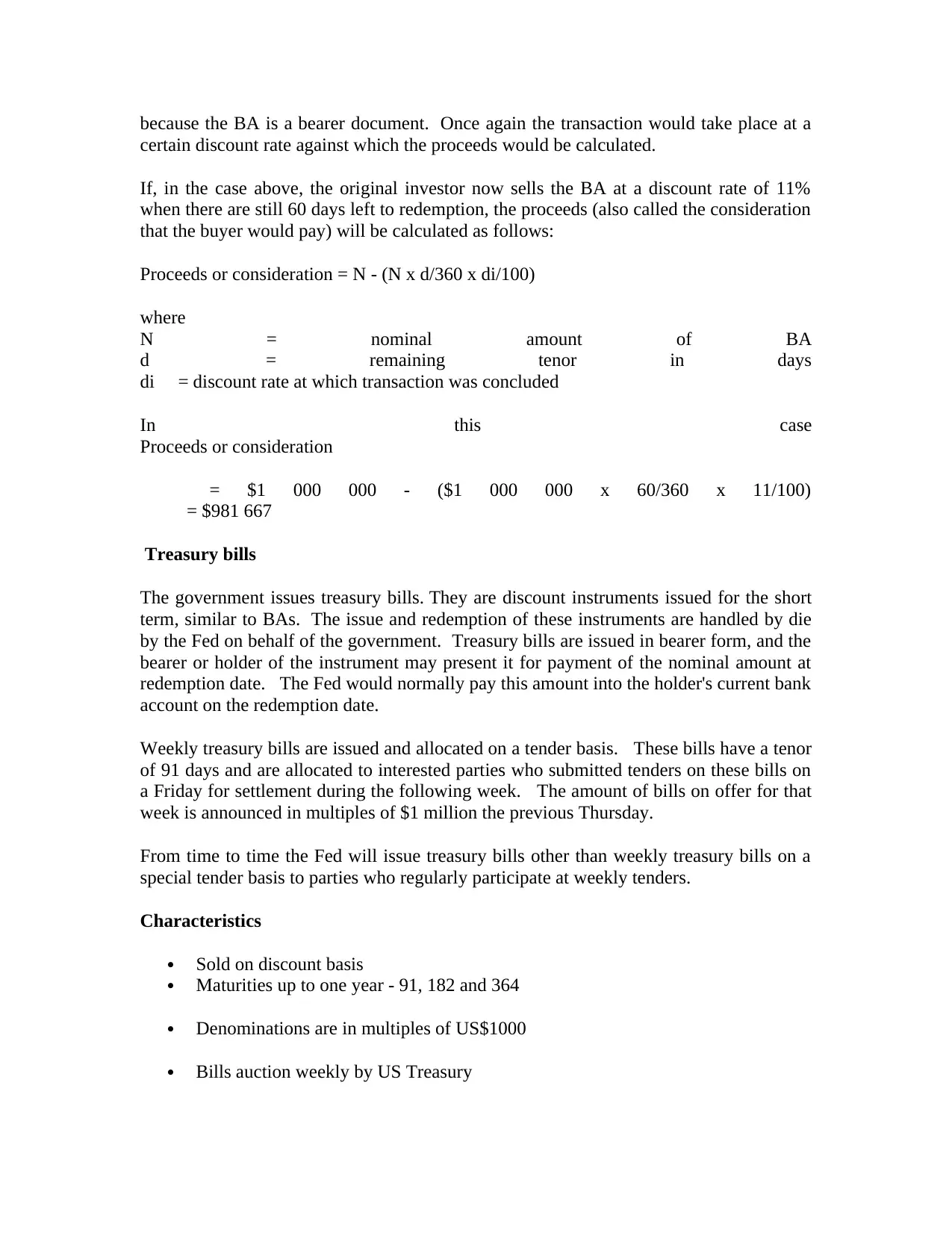

because the BA is a bearer document. Once again the transaction would take place at a

certain discount rate against which the proceeds would be calculated.

If, in the case above, the original investor now sells the BA at a discount rate of 11%

when there are still 60 days left to redemption, the proceeds (also called the consideration

that the buyer would pay) will be calculated as follows:

Proceeds or consideration = N - (N x d/360 x di/100)

where

N = nominal amount of BA

d = remaining tenor in days

di = discount rate at which transaction was concluded

In this case

Proceeds or consideration

= $1 000 000 - ($1 000 000 x 60/360 x 11/100)

= $981 667

Treasury bills

The government issues treasury bills. They are discount instruments issued for the short

term, similar to BAs. The issue and redemption of these instruments are handled by die

by the Fed on behalf of the government. Treasury bills are issued in bearer form, and the

bearer or holder of the instrument may present it for payment of the nominal amount at

redemption date. The Fed would normally pay this amount into the holder's current bank

account on the redemption date.

Weekly treasury bills are issued and allocated on a tender basis. These bills have a tenor

of 91 days and are allocated to interested parties who submitted tenders on these bills on

a Friday for settlement during the following week. The amount of bills on offer for that

week is announced in multiples of $1 million the previous Thursday.

From time to time the Fed will issue treasury bills other than weekly treasury bills on a

special tender basis to parties who regularly participate at weekly tenders.

Characteristics

Sold on discount basis

Maturities up to one year - 91, 182 and 364

Denominations are in multiples of US$1000

Bills auction weekly by US Treasury

certain discount rate against which the proceeds would be calculated.

If, in the case above, the original investor now sells the BA at a discount rate of 11%

when there are still 60 days left to redemption, the proceeds (also called the consideration

that the buyer would pay) will be calculated as follows:

Proceeds or consideration = N - (N x d/360 x di/100)

where

N = nominal amount of BA

d = remaining tenor in days

di = discount rate at which transaction was concluded

In this case

Proceeds or consideration

= $1 000 000 - ($1 000 000 x 60/360 x 11/100)

= $981 667

Treasury bills

The government issues treasury bills. They are discount instruments issued for the short

term, similar to BAs. The issue and redemption of these instruments are handled by die

by the Fed on behalf of the government. Treasury bills are issued in bearer form, and the

bearer or holder of the instrument may present it for payment of the nominal amount at

redemption date. The Fed would normally pay this amount into the holder's current bank

account on the redemption date.

Weekly treasury bills are issued and allocated on a tender basis. These bills have a tenor

of 91 days and are allocated to interested parties who submitted tenders on these bills on

a Friday for settlement during the following week. The amount of bills on offer for that

week is announced in multiples of $1 million the previous Thursday.

From time to time the Fed will issue treasury bills other than weekly treasury bills on a

special tender basis to parties who regularly participate at weekly tenders.

Characteristics

Sold on discount basis

Maturities up to one year - 91, 182 and 364

Denominations are in multiples of US$1000

Bills auction weekly by US Treasury

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

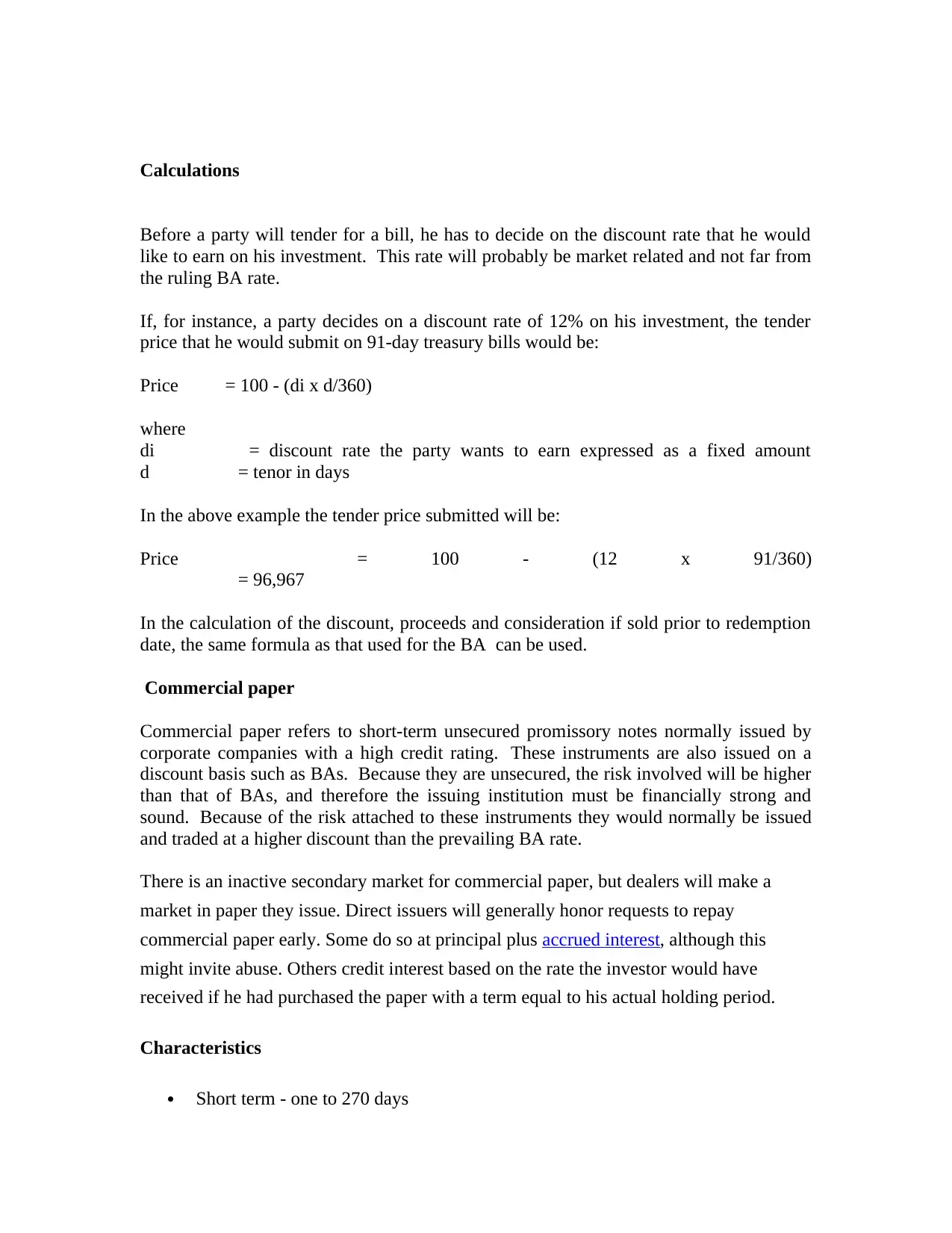

Calculations

Before a party will tender for a bill, he has to decide on the discount rate that he would

like to earn on his investment. This rate will probably be market related and not far from

the ruling BA rate.

If, for instance, a party decides on a discount rate of 12% on his investment, the tender

price that he would submit on 91-day treasury bills would be:

Price = 100 - (di x d/360)

where

di = discount rate the party wants to earn expressed as a fixed amount

d = tenor in days

In the above example the tender price submitted will be:

Price = 100 - (12 x 91/360)

= 96,967

In the calculation of the discount, proceeds and consideration if sold prior to redemption

date, the same formula as that used for the BA can be used.

Commercial paper

Commercial paper refers to short-term unsecured promissory notes normally issued by

corporate companies with a high credit rating. These instruments are also issued on a

discount basis such as BAs. Because they are unsecured, the risk involved will be higher

than that of BAs, and therefore the issuing institution must be financially strong and

sound. Because of the risk attached to these instruments they would normally be issued

and traded at a higher discount than the prevailing BA rate.

There is an inactive secondary market for commercial paper, but dealers will make a

market in paper they issue. Direct issuers will generally honor requests to repay

commercial paper early. Some do so at principal plus accrued interest, although this

might invite abuse. Others credit interest based on the rate the investor would have

received if he had purchased the paper with a term equal to his actual holding period.

Characteristics

Short term - one to 270 days

Before a party will tender for a bill, he has to decide on the discount rate that he would

like to earn on his investment. This rate will probably be market related and not far from

the ruling BA rate.

If, for instance, a party decides on a discount rate of 12% on his investment, the tender

price that he would submit on 91-day treasury bills would be:

Price = 100 - (di x d/360)

where

di = discount rate the party wants to earn expressed as a fixed amount

d = tenor in days

In the above example the tender price submitted will be:

Price = 100 - (12 x 91/360)

= 96,967

In the calculation of the discount, proceeds and consideration if sold prior to redemption

date, the same formula as that used for the BA can be used.

Commercial paper

Commercial paper refers to short-term unsecured promissory notes normally issued by

corporate companies with a high credit rating. These instruments are also issued on a

discount basis such as BAs. Because they are unsecured, the risk involved will be higher

than that of BAs, and therefore the issuing institution must be financially strong and

sound. Because of the risk attached to these instruments they would normally be issued

and traded at a higher discount than the prevailing BA rate.

There is an inactive secondary market for commercial paper, but dealers will make a

market in paper they issue. Direct issuers will generally honor requests to repay

commercial paper early. Some do so at principal plus accrued interest, although this

might invite abuse. Others credit interest based on the rate the investor would have

received if he had purchased the paper with a term equal to his actual holding period.

Characteristics

Short term - one to 270 days

Usually unsecured

Large denominations - US$100,000 and up

Issued by high quality borrowers

A wholesale money market instrument with few personal investors

Sold at a discount from par

Directly or dealer sold

Backed by bank lines of credit

Credit ratings important for issuance

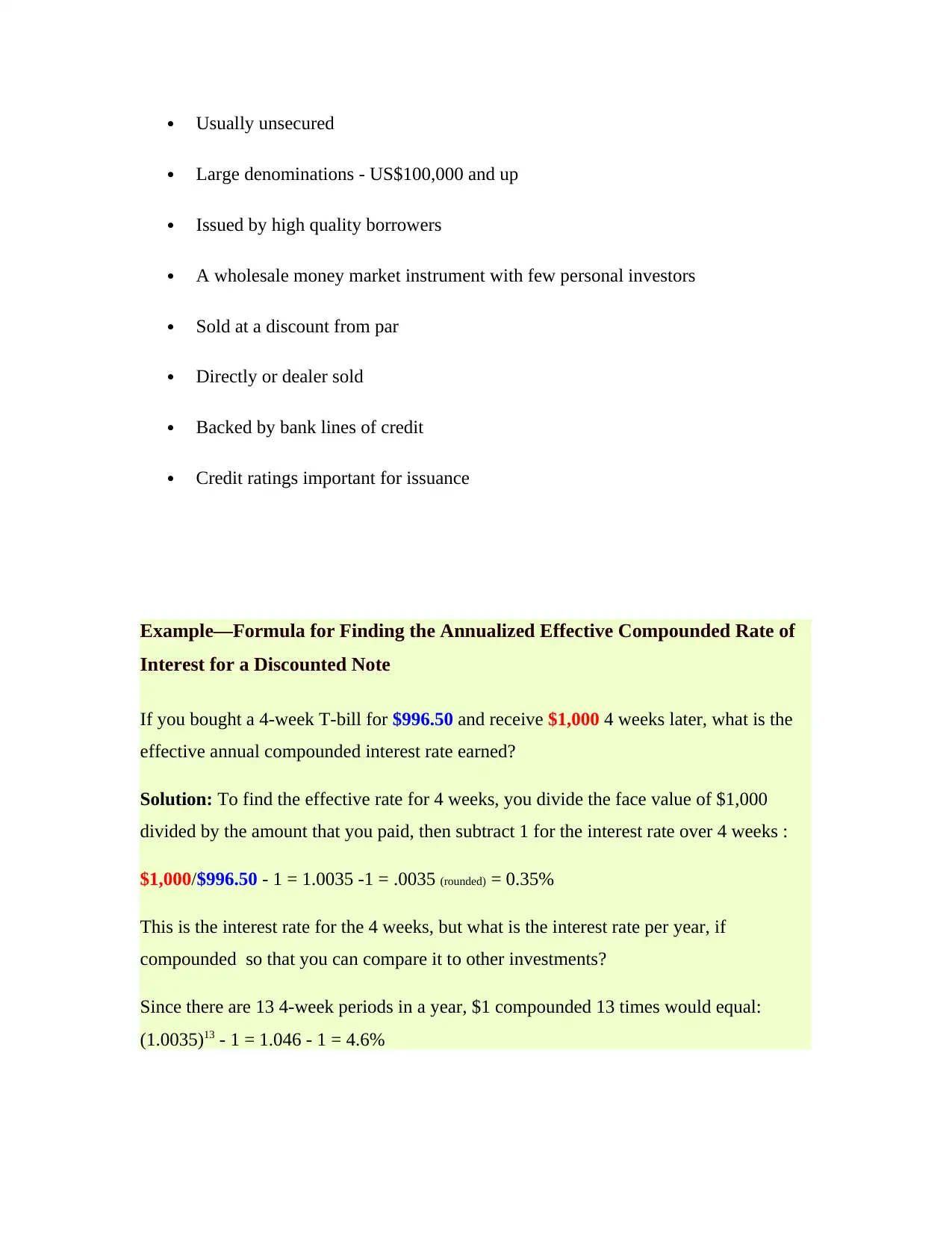

Example—Formula for Finding the Annualized Effective Compounded Rate of

Interest for a Discounted Note

If you bought a 4-week T-bill for $996.50 and receive $1,000 4 weeks later, what is the

effective annual compounded interest rate earned?

Solution: To find the effective rate for 4 weeks, you divide the face value of $1,000

divided by the amount that you paid, then subtract 1 for the interest rate over 4 weeks :

$1,000/$996.50 - 1 = 1.0035 -1 = .0035 (rounded) = 0.35%

This is the interest rate for the 4 weeks, but what is the interest rate per year, if

compounded so that you can compare it to other investments?

Since there are 13 4-week periods in a year, $1 compounded 13 times would equal:

(1.0035)13 - 1 = 1.046 - 1 = 4.6%

Large denominations - US$100,000 and up

Issued by high quality borrowers

A wholesale money market instrument with few personal investors

Sold at a discount from par

Directly or dealer sold

Backed by bank lines of credit

Credit ratings important for issuance

Example—Formula for Finding the Annualized Effective Compounded Rate of

Interest for a Discounted Note

If you bought a 4-week T-bill for $996.50 and receive $1,000 4 weeks later, what is the

effective annual compounded interest rate earned?

Solution: To find the effective rate for 4 weeks, you divide the face value of $1,000

divided by the amount that you paid, then subtract 1 for the interest rate over 4 weeks :

$1,000/$996.50 - 1 = 1.0035 -1 = .0035 (rounded) = 0.35%

This is the interest rate for the 4 weeks, but what is the interest rate per year, if

compounded so that you can compare it to other investments?

Since there are 13 4-week periods in a year, $1 compounded 13 times would equal:

(1.0035)13 - 1 = 1.046 - 1 = 4.6%

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.