Consumers'perceptions of luxury brands’CSR initiatives: An

investigation of the role of status and conspicuous consumption

Cesare Amatullia, * , 1

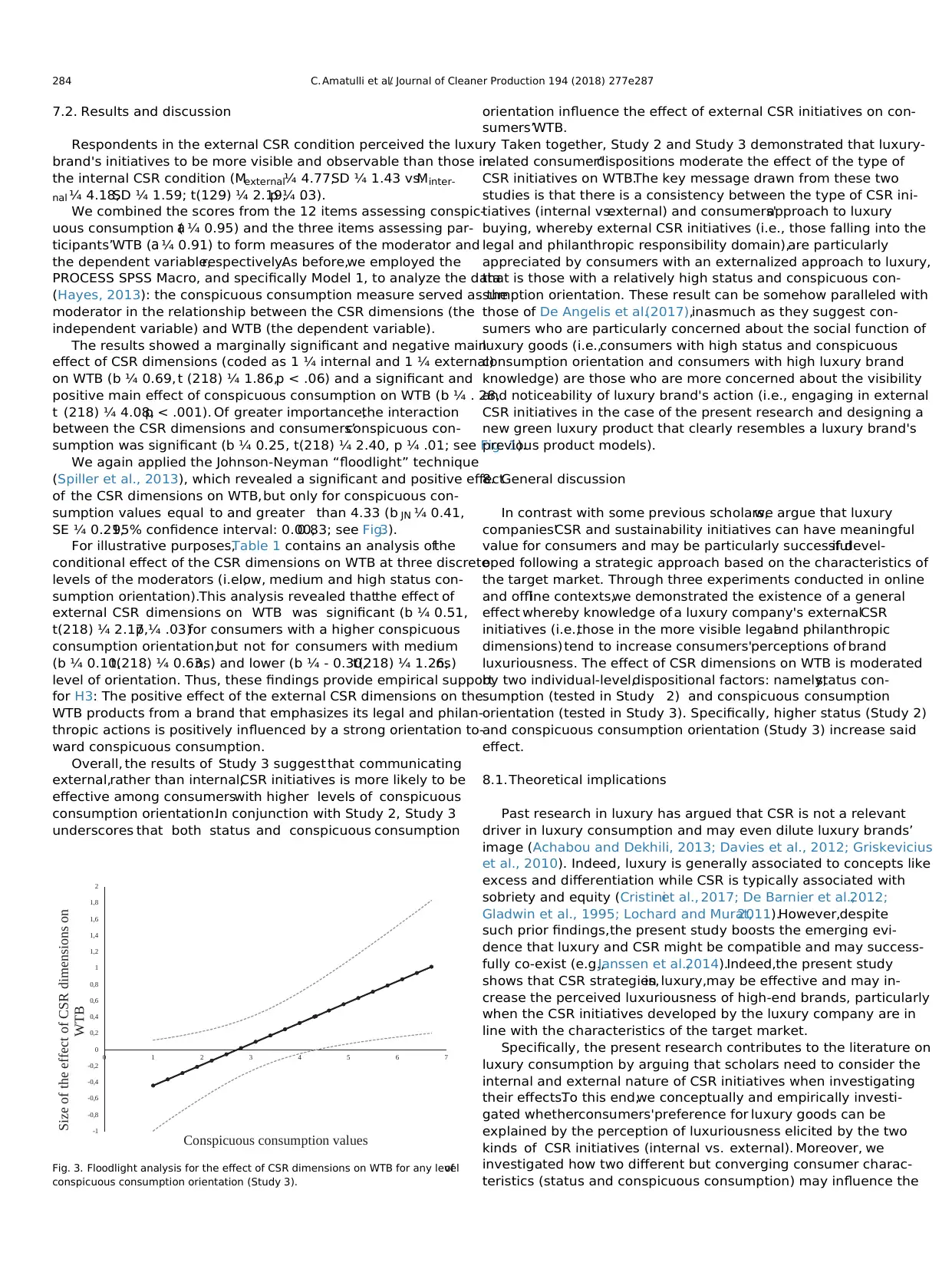

, Matteo De Angelisb

, Daniel Korschunc

, Simona Romanib

a Ionian Department of Mediterranean Legal and Economic Systems: Society,Environment,Culture,University of Bari Aldo Moro,Via Duomo,259,74123

Taranto,Italy

b Department of Business Management,LUISS University Viale Romania,32,00197 Rome,Italy

c LeBow College of Business,Drexel University,3220 Market St,Philadelphia,PA 19104,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 12 January 2018

Received in revised form

3 May 2018

Accepted 14 May 2018

Available online 17 May 2018

Keywords:

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Sustainability

Luxury marketing

Status consumption

Conspicuous consumption

a b s t r a c t

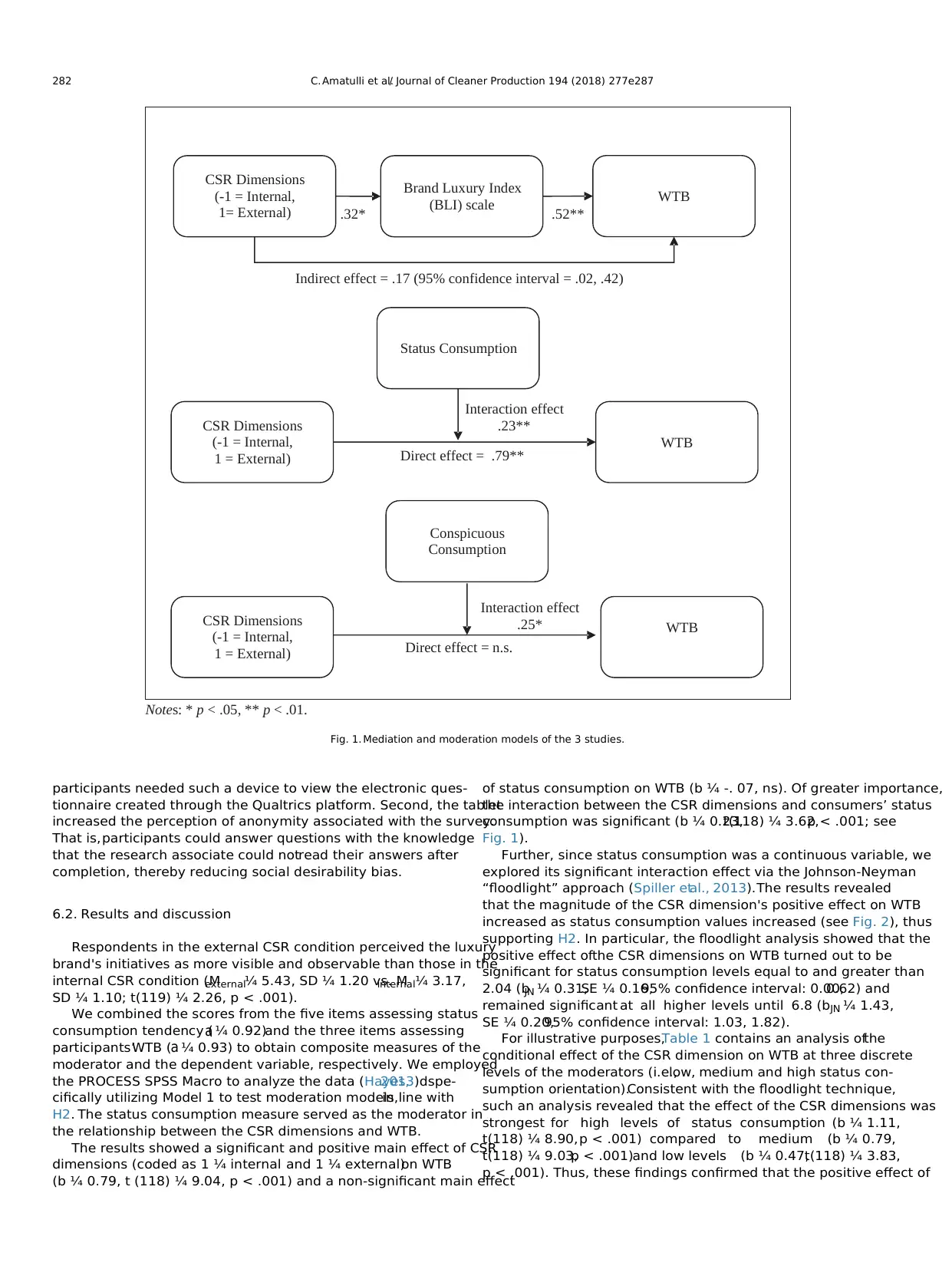

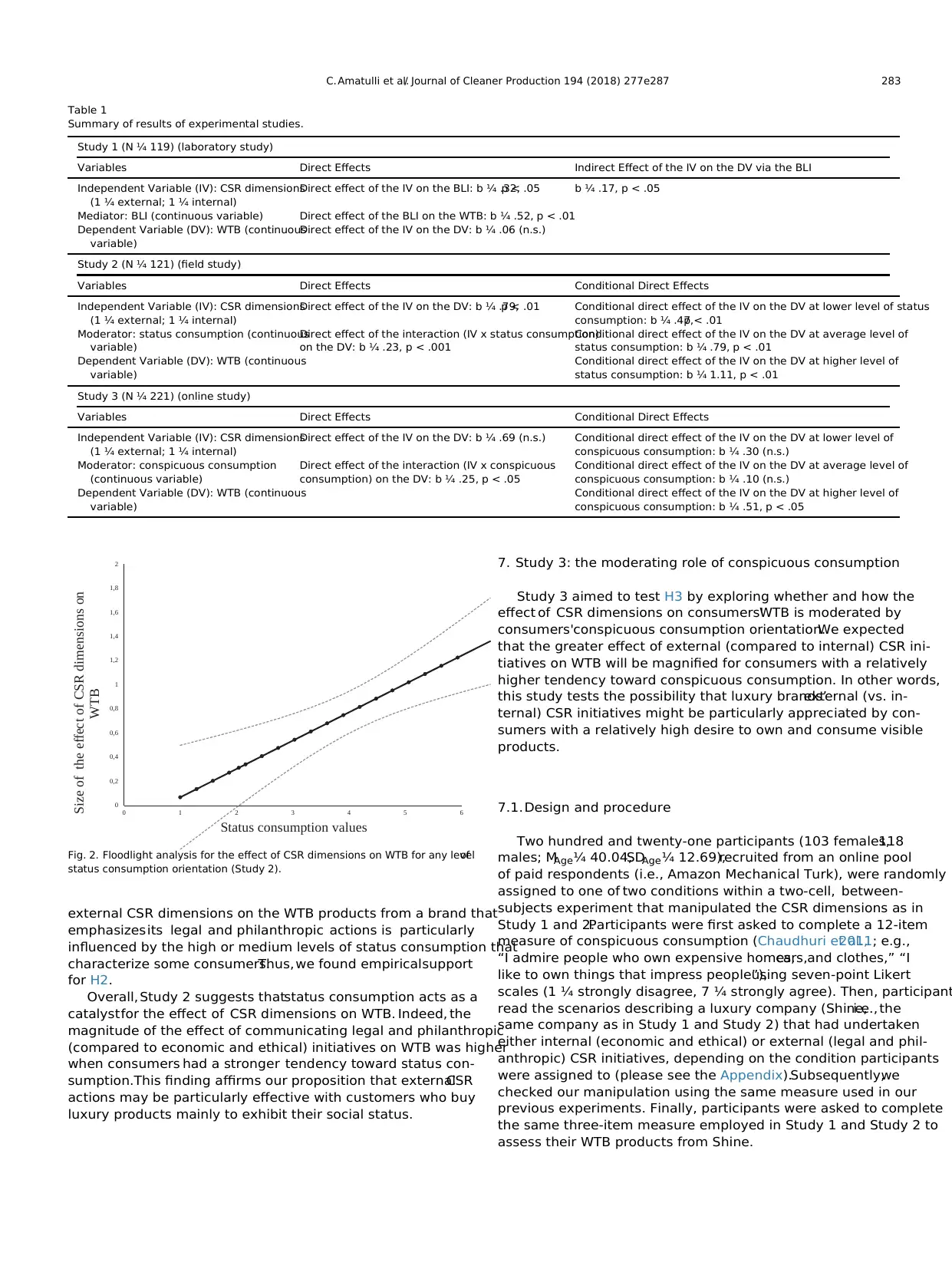

This research challenges the notion that luxury and CSR are incompatible by investigating whether and

under what conditions consumers react positively to different kinds ofCSR initiatives among luxury

companies. Extending Carroll's four-dimension model of CSR, we argue that some CSR initiatives, namely

those in the economic and ethical dimensions, are less noticeable and visible to consumers than those in

the legal and philanthropic dimensions.We categorized the former as “internal” dimensions and the

latter as “external” dimensions as part of a novel classification of Carroll's four CSR dimensions.To test

our hypotheses, we conducted three experiments e one in a laboratory, one online and one in the field e

with a total of 461 respondents.Our results demonstrate that luxury companies'external (compared to

internal) CSR initiatives increase consumers' willingness to buy; this effect is accentuated for consumers

with higher status and conspicuous consumption orientation.

© 2018 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

1. Introduction

Companiesare increasingly embracing sustainable develop-

ment and Corporate SocialResponsibility (hereafter,CSR; Kotler,

2011; Romani et al.,2016),defined as the set of discretionary ac-

tivities “demonstrating the inclusion of social and environmental

concerns in business operations and in interactions with stake-

holders” (Van Marrewijk and Werre,2003,p. 107).One survey of

over 500 experts from all 32 European countries suggests that the

importance of CSR in business will even increase in the next few

years (Kudłak et al.,2018).Notwithstanding the overallupward

trend, competing views about CSR initiatives in different sectors

still persist (e.g., Sweeney and Coughlan, 2008). For instance, Green

Public Procurement has been shown to be much more important in

the ICT and construction sectors than in the retailand clothing

sectors (Kudłak et al., 2018).Meanwhile, CSR initiatives in the

automotive and aerospace sectors are mainly focused on reducing

the purchases ofchemicals from suppliers (Lindsey,2011),and

those in the retailsector mostly involve the reduction of energy

consumption and the use of greener materials for the interiors of

the stores (e.g.,Ramos and Leal,2017).

There is variability in CSR initiatives across different sectors, and

the present research seeks to contribute to our understanding of

the sources of that variability.The present research suggests that

the extent to which CSR initiatives can be successful - or not - under

the perspective of consumers depends on the visibility of the CSR

initiatives undertaken.

More specifically,we examine the role of CSR initiatives in the

context of the luxury industry. Indeed, while the global luxury

market has been characterized by a steady growth in the last

decade (The Boston Consulting Group, 2017), it is also one that has

been particularly pressured to address social issues (Davies et al.,

2012; De Angelis et al.,2017; Janssen et al.,2014; Kapferer and

Michaut-Denizeau,2014).Consequently,luxury market strategies

have begun to systematically include CSR as a key pillar(e.g.,

Cervellon and Shammas, 2013; Winston, 2016).

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)