Taxation Law and Policy Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2020/03/04

|10

|2905

|54

AI Summary

This assignment delves into the complexities of Australian taxation law and policy. Students are tasked with analyzing various aspects, including income tax, corporate tax, and the role of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). Key concepts such as tax fairness, efficiency, and avoidance are examined. The assignment also considers the impact of international tax treaties and the evolving landscape of global taxation.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

Running head: TAXATION

Taxation

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Taxation

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Course ID

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

1TAXATION

Table of Contents

Introduction:...............................................................................................................................2

Determination of Car FBT.........................................................................................................2

Employment duties of an Itinerant Nature:................................................................................4

Car parking fringe benefit:.........................................................................................................5

FBT on accommodation:............................................................................................................5

Fringe Benefit Tax consequences of Charlie Homes.................................................................6

Conclusion:................................................................................................................................7

Reference List:...........................................................................................................................8

Table of Contents

Introduction:...............................................................................................................................2

Determination of Car FBT.........................................................................................................2

Employment duties of an Itinerant Nature:................................................................................4

Car parking fringe benefit:.........................................................................................................5

FBT on accommodation:............................................................................................................5

Fringe Benefit Tax consequences of Charlie Homes.................................................................6

Conclusion:................................................................................................................................7

Reference List:...........................................................................................................................8

2TAXATION

Introduction:

The following study is concerned with the determination of the fringe benefit

consequences of Shine Homes and Charlie. As evident from the following scenario Charlie is

an employee of Shiney Homes Pty Ltd working as the real estate agent. Homes on the other

hand performs a business of landscaping and provided Charlie with the 4 wheel drive sedan.

As stated under Section 6 of the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings and Fringe Benefit Tax

Assessment Act 1986 it lays down the circumstances under which the fringe benefit tax will

be tax will be levied on car (Miller & Oats 2016).

Determination of Car FBT

As defined under the taxation rulings of MT 2027 personal use under sub-section

136 (1) any kind of use made by an employee or associates which is not completely used in

the phase of generating taxable income of the employee will be considered as personal use

(Pope et al., 2016). However, under sub-section 136 (1) a definition on the operating cost

valuation method for commercial journey has been stated in effect of any kind of use of car

other than the personal use made by an employee (Christie, 2015). As defined under

paragraph 3 of the Miscellaneous Taxation Ruling 2027 details concerning the business

journey is required to be recorded in the logbook or identical kind of document if the business

kilometres travelled by the car are used in the determination of the personal use part of a car

for the purpose of applying the operating cost method. Hence, it is found from the case study

that Charlie travelled a total of 50,000 km relating to work. In determining the fringe benefit

of the car used by Charlie operational cost valuation method will be used in compliance with

sub-section 136 (1) of the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings of 2027 (Fleurbaey&Maniquet,

2015).

A critical question arises in determination of the personal and commercial use.

Therefore, whether the car used by the member of staff or the employee was wholly in the

phase of the generating taxable earnings of the employee (Kabinga, 2015). This comprise of

all the use that is completely made by the employee in the phase of acquiring or generating

the taxable proceeds or performing the business activities for the purpose of generating the

taxable proceeds in agreement with the sub section 136 (1). If further follows the use made in

the phase of employment by the member of staff with the employer who presented the car for

business carried on by the member of staff or an additional employment action of the

employee might make up for business use of the car for Fringe Benefit Tax (Lang, 2014).

Introduction:

The following study is concerned with the determination of the fringe benefit

consequences of Shine Homes and Charlie. As evident from the following scenario Charlie is

an employee of Shiney Homes Pty Ltd working as the real estate agent. Homes on the other

hand performs a business of landscaping and provided Charlie with the 4 wheel drive sedan.

As stated under Section 6 of the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings and Fringe Benefit Tax

Assessment Act 1986 it lays down the circumstances under which the fringe benefit tax will

be tax will be levied on car (Miller & Oats 2016).

Determination of Car FBT

As defined under the taxation rulings of MT 2027 personal use under sub-section

136 (1) any kind of use made by an employee or associates which is not completely used in

the phase of generating taxable income of the employee will be considered as personal use

(Pope et al., 2016). However, under sub-section 136 (1) a definition on the operating cost

valuation method for commercial journey has been stated in effect of any kind of use of car

other than the personal use made by an employee (Christie, 2015). As defined under

paragraph 3 of the Miscellaneous Taxation Ruling 2027 details concerning the business

journey is required to be recorded in the logbook or identical kind of document if the business

kilometres travelled by the car are used in the determination of the personal use part of a car

for the purpose of applying the operating cost method. Hence, it is found from the case study

that Charlie travelled a total of 50,000 km relating to work. In determining the fringe benefit

of the car used by Charlie operational cost valuation method will be used in compliance with

sub-section 136 (1) of the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings of 2027 (Fleurbaey&Maniquet,

2015).

A critical question arises in determination of the personal and commercial use.

Therefore, whether the car used by the member of staff or the employee was wholly in the

phase of the generating taxable earnings of the employee (Kabinga, 2015). This comprise of

all the use that is completely made by the employee in the phase of acquiring or generating

the taxable proceeds or performing the business activities for the purpose of generating the

taxable proceeds in agreement with the sub section 136 (1). If further follows the use made in

the phase of employment by the member of staff with the employer who presented the car for

business carried on by the member of staff or an additional employment action of the

employee might make up for business use of the car for Fringe Benefit Tax (Lang, 2014).

3TAXATION

Furthermore, use of car made by the employment during the phase of business that is carried

on by the member of staff might similarly be considered as the business use for this purpose.

From the given scenario of Charlie and Homes, it can be said that Charlie made the

use of the car during the course of his employment with Charlie who provided him with the

car to carry on the activities of the business. The use of car by Charlie constitutes business

use of car in producing the assessable income of the employee and hence attracts Fringe

Benefit Tax.

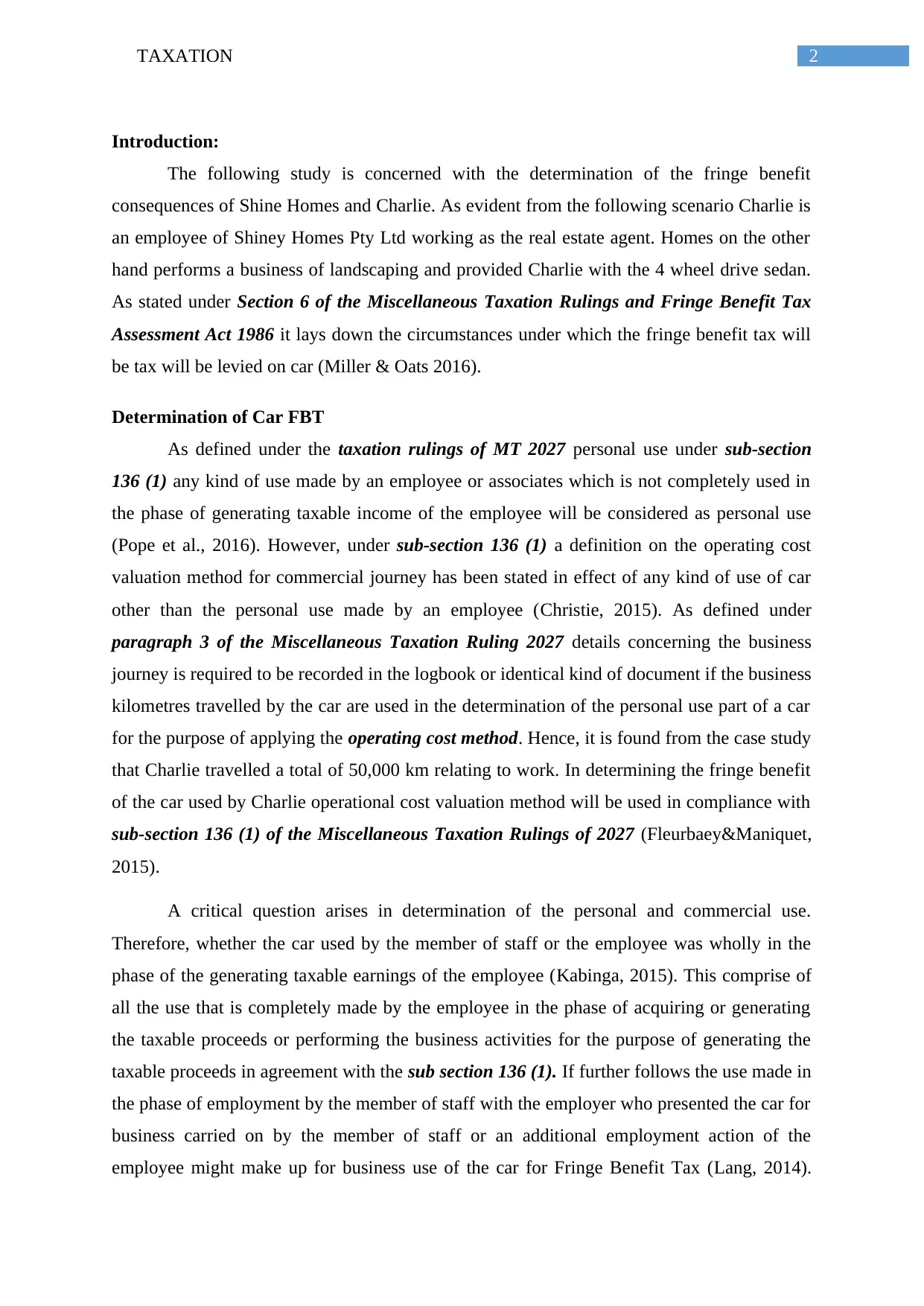

The test involved in determining the business use and private use for FBT purpose is

identical that has been defined under the income tax law in ascertaining whether the

expenditure acquired in using the car are considered deductions under section 51 of the

Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. There are evidences from the case study that expenditure

incurred by Charlie on car is for the employment use that can be completely considered for

deductions for income tax purpose (Barkoczy, 2016). In ascertaining the differences between

the personal and business use FBT can be used by raising the question whether Charlie had

occurred expenditure on the use of the car and the expenses in the present case of Charlie

would be considered as the allowable deduction for income tax.

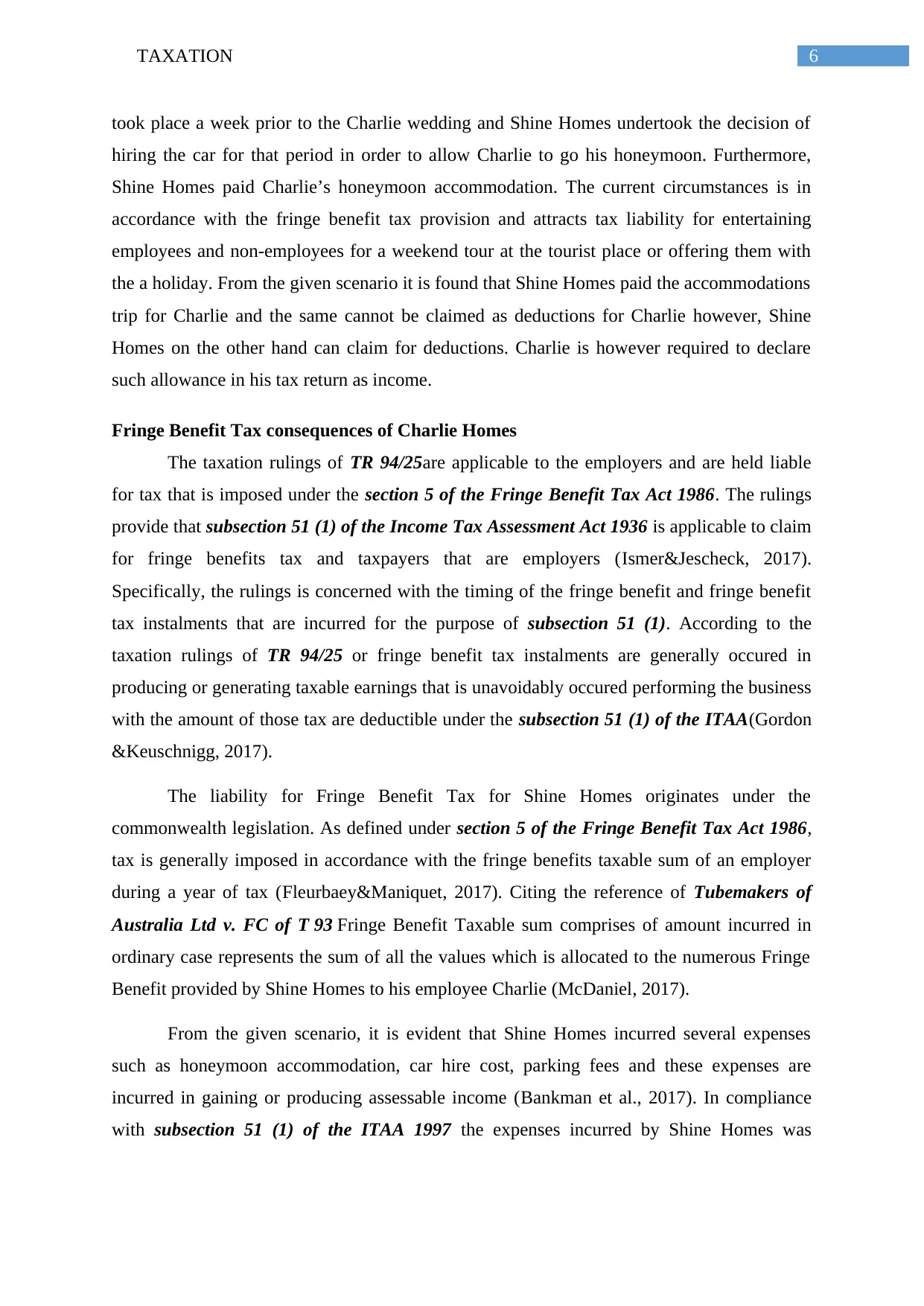

Operating Cost Method

In the Books of Charlie

For the year ended 2016/17

Particulars Amount ($)

Petrol and oil per month 6000

Repairs and Maintenance per month 10500

Registration per annum 240

Insurance per annum 960

Car parking fee 2400

20100

Gross Taxable Value (a) 6030

Employee Contribution (b) 0

Taxable Value of the benefits 6030

In consistent with the present case study of Charlie and Homes, the guidelines from

the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings of 2027 established principles relating to Income tax

(Snape& De Souza, 2016). As evident, Charlie correspondingly in compliance with the

requirement of Sub-division F of Division 3 of the income tax assessment act in ascertaining

the expenses of car occurs the ruling and Homes are deductible for the purpose of income tax

(Braithwaite, 2017).

Furthermore, use of car made by the employment during the phase of business that is carried

on by the member of staff might similarly be considered as the business use for this purpose.

From the given scenario of Charlie and Homes, it can be said that Charlie made the

use of the car during the course of his employment with Charlie who provided him with the

car to carry on the activities of the business. The use of car by Charlie constitutes business

use of car in producing the assessable income of the employee and hence attracts Fringe

Benefit Tax.

The test involved in determining the business use and private use for FBT purpose is

identical that has been defined under the income tax law in ascertaining whether the

expenditure acquired in using the car are considered deductions under section 51 of the

Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. There are evidences from the case study that expenditure

incurred by Charlie on car is for the employment use that can be completely considered for

deductions for income tax purpose (Barkoczy, 2016). In ascertaining the differences between

the personal and business use FBT can be used by raising the question whether Charlie had

occurred expenditure on the use of the car and the expenses in the present case of Charlie

would be considered as the allowable deduction for income tax.

Operating Cost Method

In the Books of Charlie

For the year ended 2016/17

Particulars Amount ($)

Petrol and oil per month 6000

Repairs and Maintenance per month 10500

Registration per annum 240

Insurance per annum 960

Car parking fee 2400

20100

Gross Taxable Value (a) 6030

Employee Contribution (b) 0

Taxable Value of the benefits 6030

In consistent with the present case study of Charlie and Homes, the guidelines from

the Miscellaneous Taxation Rulings of 2027 established principles relating to Income tax

(Snape& De Souza, 2016). As evident, Charlie correspondingly in compliance with the

requirement of Sub-division F of Division 3 of the income tax assessment act in ascertaining

the expenses of car occurs the ruling and Homes are deductible for the purpose of income tax

(Braithwaite, 2017).

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

4TAXATION

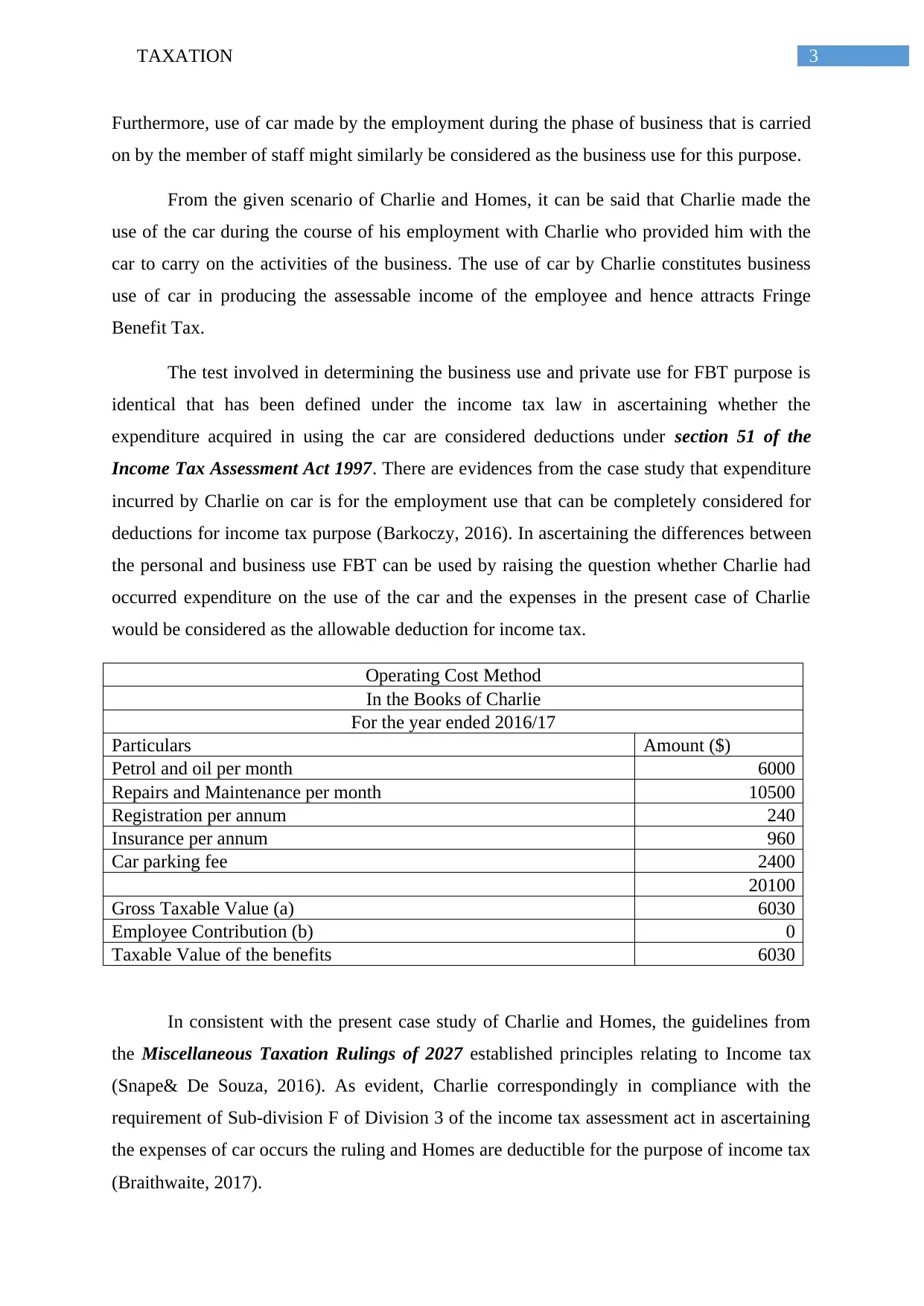

As stated in the taxation rulings of IT 112 the conclusion held in the case of Lunney

and Hayley v FCT (1958) confirmed the circumstances that travelling between residence and

an individual’s usual place of employment or trade is considered as the ordinary private travel

(Cao et al., 2015). Travelling to place of employment is regarded as the essential pre-requisite

in generating the earnings and it is not regarded in the phase of earning that income.

Therefore, the kilometres travelled by Charlie to his work will be considered as private and

the fact that Charlie used the car during the course of his employment would not change the

results. It is understood that the place of work or employment is significantly itinerant in

nature (Saad, 2014). Citing the reference of Newsom v Robertson (1952) 2 All ER 728;

(1952), the cost that is occurred by the barrister in travelling between his home to the place of

his business would be considered as expenses. The court acknowledge that traveling the

expenditure occured in travelling from home to chambers or to various courts in the course of

day does not amounted to expenses.

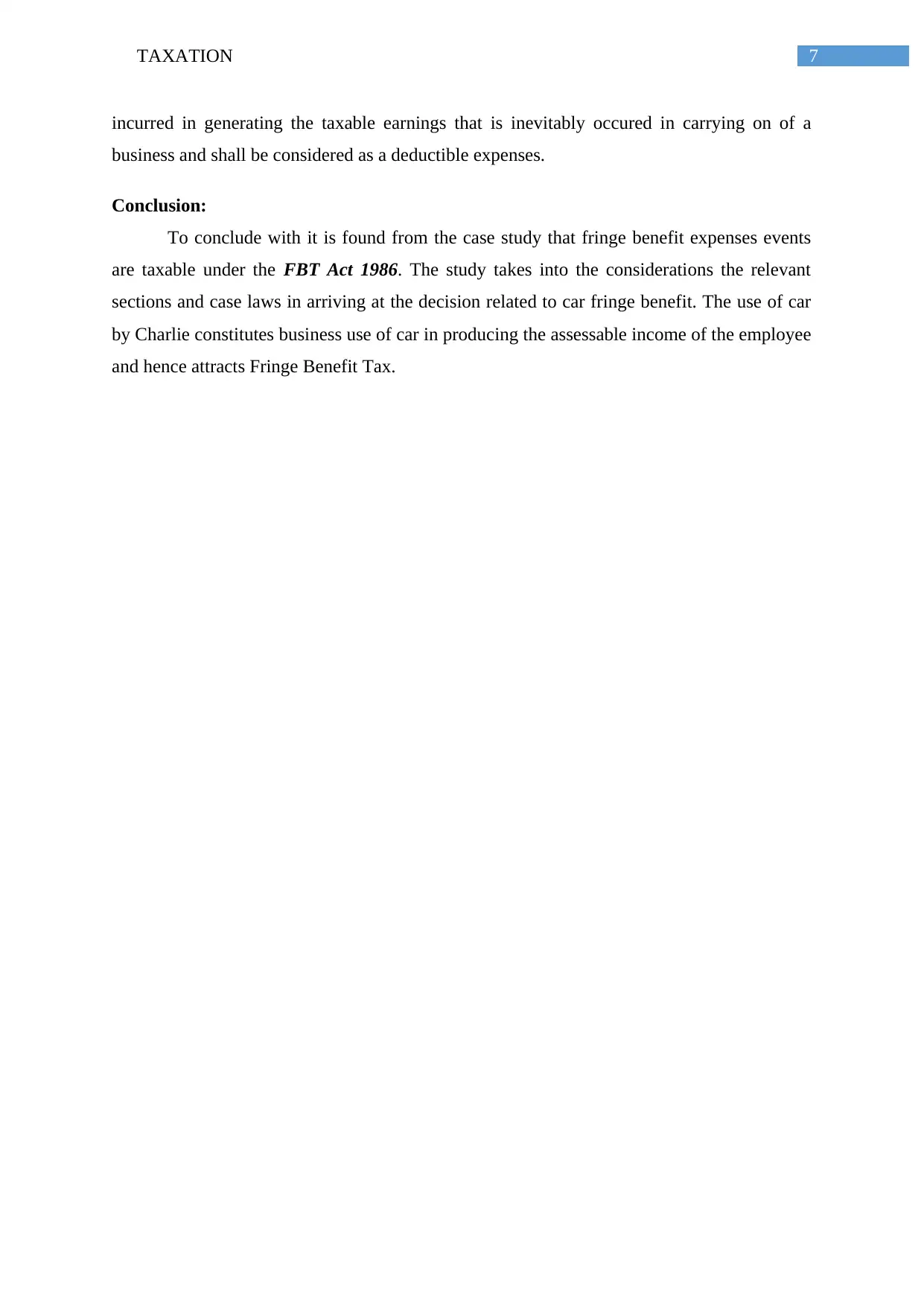

Log Book Method Computation

In the books of Homes

For the year ended 2016/17

Particulars Amount ($)

Total Kilometres Travelled 80000

Distance travelled for Business use 50000

Distance travelled for Private use 30000

Percentage of Business Use 62.5

Expenses:

Petrol and oil per month 6000

Repairs and Maintenance per month 10500

Registration per annum 240

Insurance per annum 960

Car parking fee 2400

Total Expenses 20100

Taxable value of the FBT 12562.5

Employment duties of an Itinerant Nature:

From a long time, it has been recognized that travel by an member of staff from his

home might comprise business travel on the circumstances that the nature of the office or

unemployment is inherently itinerant (Woellner et al., 2016). Citing the reference of Simon

in Taylor v Provan (1975) AC 194travel of Charlie will be regarded as employment travel

since travel formed the fundamental part of his work (Robin, 2017). Furthermore, the terms

As stated in the taxation rulings of IT 112 the conclusion held in the case of Lunney

and Hayley v FCT (1958) confirmed the circumstances that travelling between residence and

an individual’s usual place of employment or trade is considered as the ordinary private travel

(Cao et al., 2015). Travelling to place of employment is regarded as the essential pre-requisite

in generating the earnings and it is not regarded in the phase of earning that income.

Therefore, the kilometres travelled by Charlie to his work will be considered as private and

the fact that Charlie used the car during the course of his employment would not change the

results. It is understood that the place of work or employment is significantly itinerant in

nature (Saad, 2014). Citing the reference of Newsom v Robertson (1952) 2 All ER 728;

(1952), the cost that is occurred by the barrister in travelling between his home to the place of

his business would be considered as expenses. The court acknowledge that traveling the

expenditure occured in travelling from home to chambers or to various courts in the course of

day does not amounted to expenses.

Log Book Method Computation

In the books of Homes

For the year ended 2016/17

Particulars Amount ($)

Total Kilometres Travelled 80000

Distance travelled for Business use 50000

Distance travelled for Private use 30000

Percentage of Business Use 62.5

Expenses:

Petrol and oil per month 6000

Repairs and Maintenance per month 10500

Registration per annum 240

Insurance per annum 960

Car parking fee 2400

Total Expenses 20100

Taxable value of the FBT 12562.5

Employment duties of an Itinerant Nature:

From a long time, it has been recognized that travel by an member of staff from his

home might comprise business travel on the circumstances that the nature of the office or

unemployment is inherently itinerant (Woellner et al., 2016). Citing the reference of Simon

in Taylor v Provan (1975) AC 194travel of Charlie will be regarded as employment travel

since travel formed the fundamental part of his work (Robin, 2017). Furthermore, the terms

5TAXATION

of employment for Charlie required him to discharge his employment responsibilities at

additional place of employment.

According the FBT Act 1986, Charlie was using the car of his employer partly for

work purpose and partly for private purpose (Blakelock& King, 2017). Charlie incurred cost

on petrol, repairs and maintenance, insurance and registration. Therefore, Charlie for the

purpose of FBT deductions can claim the work related portion of petrol and repairs since it

was used in gaining or producing the assessable income.

Car parking fringe benefit:

A car parking fringe benefit may originate if the employer present the car parking to the

member of staff and all the subsequent state of affairs are met;

a. The car is parked at the premise which is owned or leased under the direction of the

contributor

b. The car is parked for more than four hours

c. The car is leased or owned or under the control of the employee

d. The car is presented in relation of the employee’s employment

e. The car is used by the employee to travel between the place of residence and work or

work and home for a minimum of once in day

f. There is a business-related parking place that imposes charge on a fee for all day

parking within the radius of one kilometre of the premises

As evident from the above stated conditions, Charlie has parked his car at a secure

parking for which the employer Shine Homes paid $200 each week. It is found that the car

was parked in Charlie’s garage and was under the control of the provider. The car was

provided to Charlie in respect of his employment. Furthermore, Charlie used the car to travel

from home to work and work to home each day (Fry, 2017). Therefore, a fringe will arise in

context of the Charlie and Homes can claim deductions for the parking fees paid on behalf of

his employee.

FBT on accommodation:

According to the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986, provision of entertain represents

entertainment in the form of drink or recreation, accommodation or travel in connection with

the entertainment (Williamson et al., 2017). As evident from the case study that Charlie has

incurred a minor accident and was unable to use the vehicle for a period of 2 weeks. This

of employment for Charlie required him to discharge his employment responsibilities at

additional place of employment.

According the FBT Act 1986, Charlie was using the car of his employer partly for

work purpose and partly for private purpose (Blakelock& King, 2017). Charlie incurred cost

on petrol, repairs and maintenance, insurance and registration. Therefore, Charlie for the

purpose of FBT deductions can claim the work related portion of petrol and repairs since it

was used in gaining or producing the assessable income.

Car parking fringe benefit:

A car parking fringe benefit may originate if the employer present the car parking to the

member of staff and all the subsequent state of affairs are met;

a. The car is parked at the premise which is owned or leased under the direction of the

contributor

b. The car is parked for more than four hours

c. The car is leased or owned or under the control of the employee

d. The car is presented in relation of the employee’s employment

e. The car is used by the employee to travel between the place of residence and work or

work and home for a minimum of once in day

f. There is a business-related parking place that imposes charge on a fee for all day

parking within the radius of one kilometre of the premises

As evident from the above stated conditions, Charlie has parked his car at a secure

parking for which the employer Shine Homes paid $200 each week. It is found that the car

was parked in Charlie’s garage and was under the control of the provider. The car was

provided to Charlie in respect of his employment. Furthermore, Charlie used the car to travel

from home to work and work to home each day (Fry, 2017). Therefore, a fringe will arise in

context of the Charlie and Homes can claim deductions for the parking fees paid on behalf of

his employee.

FBT on accommodation:

According to the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986, provision of entertain represents

entertainment in the form of drink or recreation, accommodation or travel in connection with

the entertainment (Williamson et al., 2017). As evident from the case study that Charlie has

incurred a minor accident and was unable to use the vehicle for a period of 2 weeks. This

6TAXATION

took place a week prior to the Charlie wedding and Shine Homes undertook the decision of

hiring the car for that period in order to allow Charlie to go his honeymoon. Furthermore,

Shine Homes paid Charlie’s honeymoon accommodation. The current circumstances is in

accordance with the fringe benefit tax provision and attracts tax liability for entertaining

employees and non-employees for a weekend tour at the tourist place or offering them with

the a holiday. From the given scenario it is found that Shine Homes paid the accommodations

trip for Charlie and the same cannot be claimed as deductions for Charlie however, Shine

Homes on the other hand can claim for deductions. Charlie is however required to declare

such allowance in his tax return as income.

Fringe Benefit Tax consequences of Charlie Homes

The taxation rulings of TR 94/25are applicable to the employers and are held liable

for tax that is imposed under the section 5 of the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986. The rulings

provide that subsection 51 (1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 is applicable to claim

for fringe benefits tax and taxpayers that are employers (Ismer&Jescheck, 2017).

Specifically, the rulings is concerned with the timing of the fringe benefit and fringe benefit

tax instalments that are incurred for the purpose of subsection 51 (1). According to the

taxation rulings of TR 94/25 or fringe benefit tax instalments are generally occured in

producing or generating taxable earnings that is unavoidably occured performing the business

with the amount of those tax are deductible under the subsection 51 (1) of the ITAA(Gordon

&Keuschnigg, 2017).

The liability for Fringe Benefit Tax for Shine Homes originates under the

commonwealth legislation. As defined under section 5 of the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986,

tax is generally imposed in accordance with the fringe benefits taxable sum of an employer

during a year of tax (Fleurbaey&Maniquet, 2017). Citing the reference of Tubemakers of

Australia Ltd v. FC of T 93 Fringe Benefit Taxable sum comprises of amount incurred in

ordinary case represents the sum of all the values which is allocated to the numerous Fringe

Benefit provided by Shine Homes to his employee Charlie (McDaniel, 2017).

From the given scenario, it is evident that Shine Homes incurred several expenses

such as honeymoon accommodation, car hire cost, parking fees and these expenses are

incurred in gaining or producing assessable income (Bankman et al., 2017). In compliance

with subsection 51 (1) of the ITAA 1997 the expenses incurred by Shine Homes was

took place a week prior to the Charlie wedding and Shine Homes undertook the decision of

hiring the car for that period in order to allow Charlie to go his honeymoon. Furthermore,

Shine Homes paid Charlie’s honeymoon accommodation. The current circumstances is in

accordance with the fringe benefit tax provision and attracts tax liability for entertaining

employees and non-employees for a weekend tour at the tourist place or offering them with

the a holiday. From the given scenario it is found that Shine Homes paid the accommodations

trip for Charlie and the same cannot be claimed as deductions for Charlie however, Shine

Homes on the other hand can claim for deductions. Charlie is however required to declare

such allowance in his tax return as income.

Fringe Benefit Tax consequences of Charlie Homes

The taxation rulings of TR 94/25are applicable to the employers and are held liable

for tax that is imposed under the section 5 of the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986. The rulings

provide that subsection 51 (1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 is applicable to claim

for fringe benefits tax and taxpayers that are employers (Ismer&Jescheck, 2017).

Specifically, the rulings is concerned with the timing of the fringe benefit and fringe benefit

tax instalments that are incurred for the purpose of subsection 51 (1). According to the

taxation rulings of TR 94/25 or fringe benefit tax instalments are generally occured in

producing or generating taxable earnings that is unavoidably occured performing the business

with the amount of those tax are deductible under the subsection 51 (1) of the ITAA(Gordon

&Keuschnigg, 2017).

The liability for Fringe Benefit Tax for Shine Homes originates under the

commonwealth legislation. As defined under section 5 of the Fringe Benefit Tax Act 1986,

tax is generally imposed in accordance with the fringe benefits taxable sum of an employer

during a year of tax (Fleurbaey&Maniquet, 2017). Citing the reference of Tubemakers of

Australia Ltd v. FC of T 93 Fringe Benefit Taxable sum comprises of amount incurred in

ordinary case represents the sum of all the values which is allocated to the numerous Fringe

Benefit provided by Shine Homes to his employee Charlie (McDaniel, 2017).

From the given scenario, it is evident that Shine Homes incurred several expenses

such as honeymoon accommodation, car hire cost, parking fees and these expenses are

incurred in gaining or producing assessable income (Bankman et al., 2017). In compliance

with subsection 51 (1) of the ITAA 1997 the expenses incurred by Shine Homes was

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7TAXATION

incurred in generating the taxable earnings that is inevitably occured in carrying on of a

business and shall be considered as a deductible expenses.

Conclusion:

To conclude with it is found from the case study that fringe benefit expenses events

are taxable under the FBT Act 1986. The study takes into the considerations the relevant

sections and case laws in arriving at the decision related to car fringe benefit. The use of car

by Charlie constitutes business use of car in producing the assessable income of the employee

and hence attracts Fringe Benefit Tax.

incurred in generating the taxable earnings that is inevitably occured in carrying on of a

business and shall be considered as a deductible expenses.

Conclusion:

To conclude with it is found from the case study that fringe benefit expenses events

are taxable under the FBT Act 1986. The study takes into the considerations the relevant

sections and case laws in arriving at the decision related to car fringe benefit. The use of car

by Charlie constitutes business use of car in producing the assessable income of the employee

and hence attracts Fringe Benefit Tax.

8TAXATION

Reference List:

Bankman, J., Shaviro, D. N., Stark, K. J., &Kleinbard, E. D. (2017). Federal Income

Taxation. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

Barkoczy, S. (2016). Foundations of Taxation Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

Blakelock, S., & King, P. (2017). Taxation law: The advance of ATO data matching. Proctor,

The, 37(6), 18.

Braithwaite, V. (Ed.). (2017). Taxing democracy: Understanding tax avoidance and evasion.

Routledge.

Cao, L., Hosking, A., Kouparitsas, M., Mullaly, D., Rimmer, X., Shi, Q., ...&Wende, S.

(2015). Understanding the economy-wide efficiency and incidence of major

Australian taxes. Treasury WP, 1.

Christie, M. (2015). Principles of Taxation Law 2015.

Fleurbaey, M., &Maniquet, F. (2015). Optimal taxation theory and principles of fairness (No.

2015005). Universitécatholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and

Econometrics (CORE).

Fleurbaey, M., &Maniquet, F. (2017). Optimal income taxation theory and principles of

fairness (No. UCL-UniversitéCatholique de Louvain).

Fry, M. (2017). Australian taxation of offshore hubs: an examination of the law on the ability

of Australia to tax economic activity in offshore hubs and the position of the

Australian Taxation Office. The APPEA Journal, 57(1), 49-63.

Gordon, R., &Keuschnigg, C. (2017). Introduction on Trans-Atlantic Public Economics

Seminar: Personal Income Taxation and Household Behavior.

Ismer, R., &Jescheck, C. (2017). The Substantive Scope of Tax Treaties in a Post-BEPS

World: Article 2 OECD MC (Taxes Covered) and the Rise of New

Taxes. Intertax, 45(5), 382-390.

Kabinga, M. (2015). Established principles of taxation. Tax justice & poverty.

Lang, M. (2014). Introduction to the law of double taxation conventions. LindeVerlag

GmbH.

Reference List:

Bankman, J., Shaviro, D. N., Stark, K. J., &Kleinbard, E. D. (2017). Federal Income

Taxation. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

Barkoczy, S. (2016). Foundations of Taxation Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

Blakelock, S., & King, P. (2017). Taxation law: The advance of ATO data matching. Proctor,

The, 37(6), 18.

Braithwaite, V. (Ed.). (2017). Taxing democracy: Understanding tax avoidance and evasion.

Routledge.

Cao, L., Hosking, A., Kouparitsas, M., Mullaly, D., Rimmer, X., Shi, Q., ...&Wende, S.

(2015). Understanding the economy-wide efficiency and incidence of major

Australian taxes. Treasury WP, 1.

Christie, M. (2015). Principles of Taxation Law 2015.

Fleurbaey, M., &Maniquet, F. (2015). Optimal taxation theory and principles of fairness (No.

2015005). Universitécatholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and

Econometrics (CORE).

Fleurbaey, M., &Maniquet, F. (2017). Optimal income taxation theory and principles of

fairness (No. UCL-UniversitéCatholique de Louvain).

Fry, M. (2017). Australian taxation of offshore hubs: an examination of the law on the ability

of Australia to tax economic activity in offshore hubs and the position of the

Australian Taxation Office. The APPEA Journal, 57(1), 49-63.

Gordon, R., &Keuschnigg, C. (2017). Introduction on Trans-Atlantic Public Economics

Seminar: Personal Income Taxation and Household Behavior.

Ismer, R., &Jescheck, C. (2017). The Substantive Scope of Tax Treaties in a Post-BEPS

World: Article 2 OECD MC (Taxes Covered) and the Rise of New

Taxes. Intertax, 45(5), 382-390.

Kabinga, M. (2015). Established principles of taxation. Tax justice & poverty.

Lang, M. (2014). Introduction to the law of double taxation conventions. LindeVerlag

GmbH.

9TAXATION

McDaniel, P. R. (2017). FEDERAL INCOME TAXATION. Foundation Press.

Miller, A., & Oats, L. (2016). Principles of international taxation. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pope, T. R., Rupert, T. J., & Anderson, K. E. (2016). Pearson's Federal Taxation 2017

Individuals. Pearson.

ROBIN, H. (2017). AUSTRALIAN TAXATION LAW 2017. OXFORD University Press.

Saad, N. (2014). Tax knowledge, tax complexity and tax compliance: Taxpayers’

view. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 1069-1075.

Snape, J., & De Souza, J. (2016). Environmental taxation law: policy, contexts and practice.

Routledge.

Williamson, A., Luke, B., Leat, D., &Furneaux, C. (2017). Founders, Families, and Futures:

Perspectives on the Accountability of Australian Private Ancillary Funds. Nonprofit

and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 0899764017703711.

Woellner, R., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C., & Pinto, D. (2016). Australian Taxation

Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

McDaniel, P. R. (2017). FEDERAL INCOME TAXATION. Foundation Press.

Miller, A., & Oats, L. (2016). Principles of international taxation. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pope, T. R., Rupert, T. J., & Anderson, K. E. (2016). Pearson's Federal Taxation 2017

Individuals. Pearson.

ROBIN, H. (2017). AUSTRALIAN TAXATION LAW 2017. OXFORD University Press.

Saad, N. (2014). Tax knowledge, tax complexity and tax compliance: Taxpayers’

view. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 1069-1075.

Snape, J., & De Souza, J. (2016). Environmental taxation law: policy, contexts and practice.

Routledge.

Williamson, A., Luke, B., Leat, D., &Furneaux, C. (2017). Founders, Families, and Futures:

Perspectives on the Accountability of Australian Private Ancillary Funds. Nonprofit

and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 0899764017703711.

Woellner, R., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C., & Pinto, D. (2016). Australian Taxation

Law 2016. OUP Catalogue.

1 out of 10

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

© 2024 | Zucol Services PVT LTD | All rights reserved.