Unfreezing Change as Three Steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin's Legacy for Change Management - A Critical Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/23

|28

|18790

|488

AI Summary

Read a critical analysis of Kurt Lewin's 'changing as three steps' model for change management. Understand the dubious assumptions and the significance of CATS in Lewin's writing. Explore the future directions for teaching and researching change in organizations.

Contribute Materials

Your contribution can guide someone’s learning journey. Share your

documents today.

human relations

2016, Vol. 69(1) 33 –60

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726715577707

hum.sagepub.com

human relations

Unfreezing change as three

steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s

legacy for change management

Stephen Cummings

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Todd Bridgman

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Kenneth G Brown

University of Iowa, USA

Abstract

Kurt Lewin’s ‘changing as three steps’ (unfreezing changing refreezing) is r

by many as the classic or fundamental approach to managing change. Lewin h

criticized by scholars for over-simplifying the change process and has been def

others against such charges. However, what has remained unquestioned is the

foundational significance. It is sometimes traced (if it is traced at all) to the firs

ever published in Human Relations. Based on a comparison of what Lewin wrot

changing as three steps with how this is presented in later works, we argue tha

never developed such a model and it took form after his death. We investigate

why ‘changing as three steps’ came to be understood as the foundation of the

subfield of change management and to influence change theory and practice t

and how questioning this supposed foundation can encourage innovation.

Keywords

CATS, changing as three steps, change management, Kurt Lewin, managemen

Michel Foucault

Corresponding author:

Stephen Cummings, Victoria Business School, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Z

Email: stephen.cummings@vuw.ac.nz

577707 HUM0010.1177/0018726715577707Human Relations Bridgman et al.

research-article 2015

2016, Vol. 69(1) 33 –60

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726715577707

hum.sagepub.com

human relations

Unfreezing change as three

steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s

legacy for change management

Stephen Cummings

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Todd Bridgman

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Kenneth G Brown

University of Iowa, USA

Abstract

Kurt Lewin’s ‘changing as three steps’ (unfreezing changing refreezing) is r

by many as the classic or fundamental approach to managing change. Lewin h

criticized by scholars for over-simplifying the change process and has been def

others against such charges. However, what has remained unquestioned is the

foundational significance. It is sometimes traced (if it is traced at all) to the firs

ever published in Human Relations. Based on a comparison of what Lewin wrot

changing as three steps with how this is presented in later works, we argue tha

never developed such a model and it took form after his death. We investigate

why ‘changing as three steps’ came to be understood as the foundation of the

subfield of change management and to influence change theory and practice t

and how questioning this supposed foundation can encourage innovation.

Keywords

CATS, changing as three steps, change management, Kurt Lewin, managemen

Michel Foucault

Corresponding author:

Stephen Cummings, Victoria Business School, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Z

Email: stephen.cummings@vuw.ac.nz

577707 HUM0010.1177/0018726715577707Human Relations Bridgman et al.

research-article 2015

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

34 Human Relations 69(1)

The fundamental assumptions underlying any change in a human system are derived originally

from Kurt Lewin (1947). (Schein, 2010: 299)

Kurt Lewin is widely considered the founding father of change management, with his

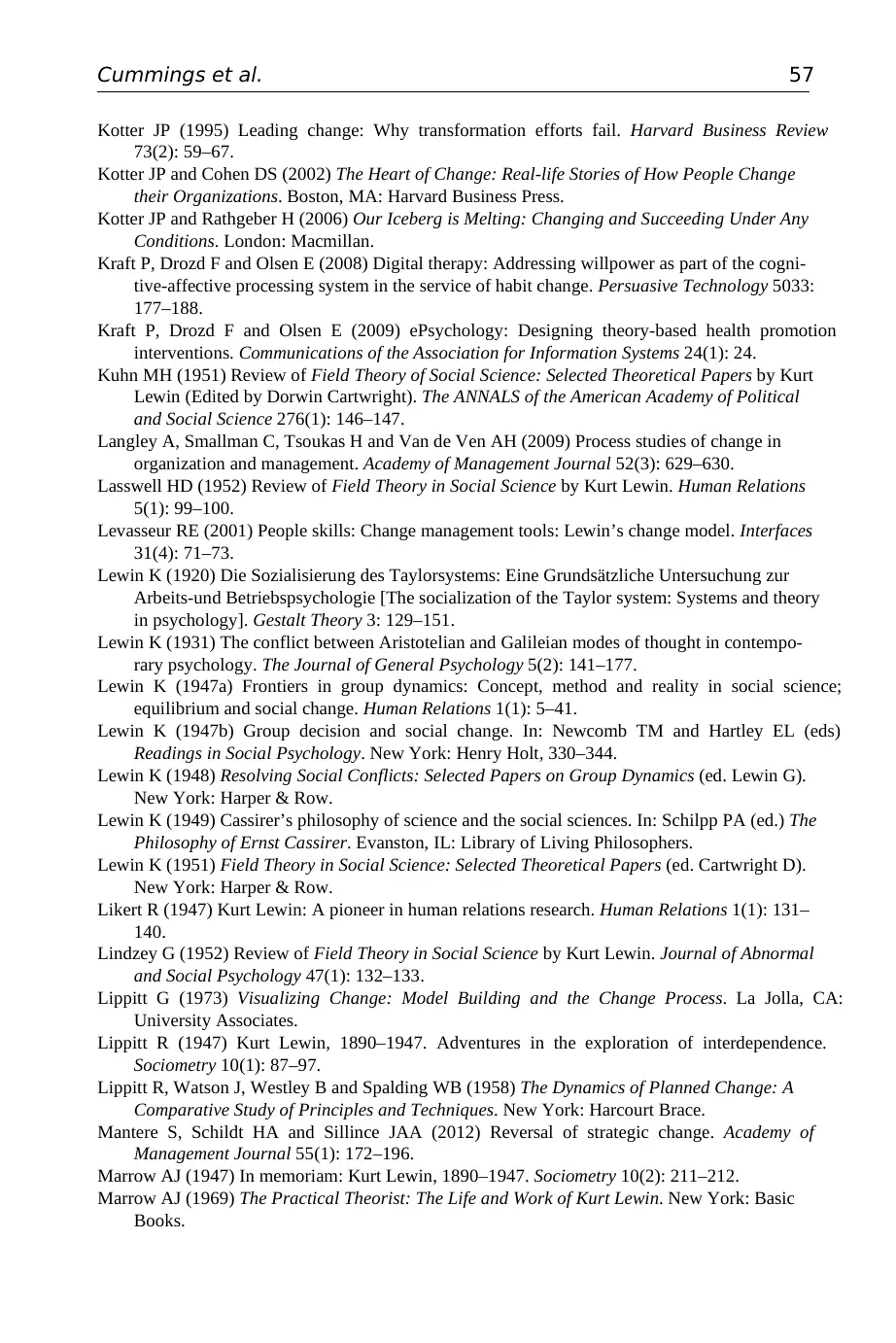

unfreeze–change–refreeze or ‘changing as three steps’ (CATS) (see Figure 1 above)

regarded as the ‘fundamental’ or ‘classic’ approach to, or classic ‘paradigm’ for, managing

change (Robbins and Judge, 2009: 625; Sonenshein, 2010: 478; Waddell, 2007: 22). The

study of change management has subsequently ‘followed Lewin’ (Jeffcutt, 1996: 173), ‘the

intellectual father of contemporary theories’ (Schein, 1988: 239). CATS has subsequently

‘dominated almost all western theories of change over the past fifty years’ (Michaels, 2001:

116). Academics claim that all theories of change are ‘reducible to this one idea of Kurt

Lewin’s’ (Hendry, 1996: 624), and practitioners boast that ‘the most powerful tool in my

toolbox is Kurt Lewin’s simple three-step change model’ (Levasseur, 2001: 71).

Many praise Lewin, the man of science, the ‘great experimentalist’ (Marrow, 1969:

ix), for providing the solid basis on which change management has developed.

Management textbooks begin their discussions on how the field of managing change

developed with Lewin’s ‘classic model’ and use it as an organizing schema. The follow-

ing words of Edgar Schein describe the regard that Lewin came to be held in:

I am struck once again by the depth of Lewin’s insight and the seminal nature of his concepts

and methods . . . [they] have deeply enriched our understanding of how change happens and

what role change agents can and must play. (Schein, 1996: 46)

CATS has come to be regarded both as an objective self-evident truth and an idea with a

noble provenance.

In recent years, some have disparaged Lewin for advancing an overly simplistic model.

For example, Kanter et al. (1992: 10) claim that ‘Lewin’s . . . quaintly linear and static con-

ception – the organization as an ice cube – is so wildly inappropriate that this is difficult to

see why it has not only survived but prospered’. Child (2005: 293) points out that Lewin’s

rigid idea of ‘refreezing’ is inappropriate in today’s complex world that requires flexibility

and adaptation. And Clegg et al. (2005: 376) are critical of the way in which Lewin’s ‘simple

chain of unfreeze, move, refreeze [which has become] the template for most change pro-

grams’, is just a re-packaging of a mechanistic philosophy behind ‘Taylor’s (1911) concept

of scientific management’. Yet others have leapt to Lewin’s defence, claiming that the rep-

resentation of his work and CATS is one-sided and partial. They claim that CATS represents

just a quarter of Lewin’s canon and must be understood in concert with his other ‘three pil-

lars’: field theory; group dynamics and action research (Burnes, 2004a, 2004b); and that

contemporary understandings of field theory neglect Lewin’s concern with gestalt psychol-

ogy and conventional topology (Burnes and Cooke, 2013). But even those who seek to cor-

rect misinterpretations of Lewin’s other ideas relating to change, couch these within a belief

in the foundational importance of CATS (Dent and Goldberg, 1999).

unfreeze change refreeze

Figure 1. Change as three steps.

The fundamental assumptions underlying any change in a human system are derived originally

from Kurt Lewin (1947). (Schein, 2010: 299)

Kurt Lewin is widely considered the founding father of change management, with his

unfreeze–change–refreeze or ‘changing as three steps’ (CATS) (see Figure 1 above)

regarded as the ‘fundamental’ or ‘classic’ approach to, or classic ‘paradigm’ for, managing

change (Robbins and Judge, 2009: 625; Sonenshein, 2010: 478; Waddell, 2007: 22). The

study of change management has subsequently ‘followed Lewin’ (Jeffcutt, 1996: 173), ‘the

intellectual father of contemporary theories’ (Schein, 1988: 239). CATS has subsequently

‘dominated almost all western theories of change over the past fifty years’ (Michaels, 2001:

116). Academics claim that all theories of change are ‘reducible to this one idea of Kurt

Lewin’s’ (Hendry, 1996: 624), and practitioners boast that ‘the most powerful tool in my

toolbox is Kurt Lewin’s simple three-step change model’ (Levasseur, 2001: 71).

Many praise Lewin, the man of science, the ‘great experimentalist’ (Marrow, 1969:

ix), for providing the solid basis on which change management has developed.

Management textbooks begin their discussions on how the field of managing change

developed with Lewin’s ‘classic model’ and use it as an organizing schema. The follow-

ing words of Edgar Schein describe the regard that Lewin came to be held in:

I am struck once again by the depth of Lewin’s insight and the seminal nature of his concepts

and methods . . . [they] have deeply enriched our understanding of how change happens and

what role change agents can and must play. (Schein, 1996: 46)

CATS has come to be regarded both as an objective self-evident truth and an idea with a

noble provenance.

In recent years, some have disparaged Lewin for advancing an overly simplistic model.

For example, Kanter et al. (1992: 10) claim that ‘Lewin’s . . . quaintly linear and static con-

ception – the organization as an ice cube – is so wildly inappropriate that this is difficult to

see why it has not only survived but prospered’. Child (2005: 293) points out that Lewin’s

rigid idea of ‘refreezing’ is inappropriate in today’s complex world that requires flexibility

and adaptation. And Clegg et al. (2005: 376) are critical of the way in which Lewin’s ‘simple

chain of unfreeze, move, refreeze [which has become] the template for most change pro-

grams’, is just a re-packaging of a mechanistic philosophy behind ‘Taylor’s (1911) concept

of scientific management’. Yet others have leapt to Lewin’s defence, claiming that the rep-

resentation of his work and CATS is one-sided and partial. They claim that CATS represents

just a quarter of Lewin’s canon and must be understood in concert with his other ‘three pil-

lars’: field theory; group dynamics and action research (Burnes, 2004a, 2004b); and that

contemporary understandings of field theory neglect Lewin’s concern with gestalt psychol-

ogy and conventional topology (Burnes and Cooke, 2013). But even those who seek to cor-

rect misinterpretations of Lewin’s other ideas relating to change, couch these within a belief

in the foundational importance of CATS (Dent and Goldberg, 1999).

unfreeze change refreeze

Figure 1. Change as three steps.

Cummings et al. 35

It seems that everybody in the management literature accepts CATS’ pre-eminence as

a foundation upon which the field of change management is built. We argue that CATS

was not as significant in Lewin’s writing as both his critics and supporters have either

assumed or would have us believe. This foundation of change management has less to do

with what Lewin actually wrote and more to do with others’ repackaging and marketing.

By adopting a Foucauldian approach, we first outline the dubious assumptions held

about Lewin and CATS, how this framework and the noble founder claimed to have

discovered it took form as a foundation of change management, and was then further

developed to fit the narrative of a field that has claimed to build on and advance beyond

it. In this light, it is little wonder that those who know only a little of Lewin are surprised

that he could have been so simplistic, and that those with a stake in seeing the field of

change management develop and grow would see more sophistication and complexity in

CATS that others had supposedly missed.

By going back and looking at what Lewin wrote (particularly the most commonly

cited reference for CATS, ‘Lewin, 1947’: the first article ever published in Human

Relations published just weeks after Lewin’s death), we see that what we know of CATS

today is largely a post hoc reconstruction. Our forensic examination of the past is not,

however, an end in itself. Rather, it encourages us to think differently about the future of

change management that we can collectively create. In that spirit, we conclude by offer-

ing two alternative future directions for teaching and researching change in organization

inspired by returning to ‘Lewin, 1947’ and reading it anew.

Dubious assumptions

Students of change management, and management generally, are informed that Lewin

was a great scientist with a keen interest in management, that discovering CATS was one

of his greatest endeavours, and that his episodic and simplistic approach to managing

change has subsequently been built upon and surpassed. However, the more that we

looked at the history of CATS, the more the anomalies between the accepted view today,

and what Lewin actually wrote, came into view.

Our first observation was that referencing of Lewin’s work in this regard is unusu-

ally lax. A footnote to an article by Schein (1996) on Lewin and CATS explains that:

I have deliberately avoided giving specific references to Lewin’s work because it is his basic

philosophy and concepts that have influenced me, and these run through all of his work as well

as the work of so many others who have founded the field of group dynamics and organization

development. (Schein, 1996: 27)

This explanation of the unusual practice of writing an article about a theorist who has been

a great influence without making any references to his work, despite referencing the work

of others who have been less influential, encouraged us to look further. Most who write

about CATS, if they cite anything, cite ‘Lewin, 1951’, Field Theory in Social Science. This

is not a book written by Lewin but an ‘edited compilation of his scattered papers’ (Shea,

1951: 65) published four years after his death in 1947. Field Theory was edited by Dorwin

Cartwright as a second companion volume to an earlier collection of Lewin’s works com-

piled by Kurt Lewin’s widow, with a foreword by Gordon Allport (Lewin, 1948).

It seems that everybody in the management literature accepts CATS’ pre-eminence as

a foundation upon which the field of change management is built. We argue that CATS

was not as significant in Lewin’s writing as both his critics and supporters have either

assumed or would have us believe. This foundation of change management has less to do

with what Lewin actually wrote and more to do with others’ repackaging and marketing.

By adopting a Foucauldian approach, we first outline the dubious assumptions held

about Lewin and CATS, how this framework and the noble founder claimed to have

discovered it took form as a foundation of change management, and was then further

developed to fit the narrative of a field that has claimed to build on and advance beyond

it. In this light, it is little wonder that those who know only a little of Lewin are surprised

that he could have been so simplistic, and that those with a stake in seeing the field of

change management develop and grow would see more sophistication and complexity in

CATS that others had supposedly missed.

By going back and looking at what Lewin wrote (particularly the most commonly

cited reference for CATS, ‘Lewin, 1947’: the first article ever published in Human

Relations published just weeks after Lewin’s death), we see that what we know of CATS

today is largely a post hoc reconstruction. Our forensic examination of the past is not,

however, an end in itself. Rather, it encourages us to think differently about the future of

change management that we can collectively create. In that spirit, we conclude by offer-

ing two alternative future directions for teaching and researching change in organization

inspired by returning to ‘Lewin, 1947’ and reading it anew.

Dubious assumptions

Students of change management, and management generally, are informed that Lewin

was a great scientist with a keen interest in management, that discovering CATS was one

of his greatest endeavours, and that his episodic and simplistic approach to managing

change has subsequently been built upon and surpassed. However, the more that we

looked at the history of CATS, the more the anomalies between the accepted view today,

and what Lewin actually wrote, came into view.

Our first observation was that referencing of Lewin’s work in this regard is unusu-

ally lax. A footnote to an article by Schein (1996) on Lewin and CATS explains that:

I have deliberately avoided giving specific references to Lewin’s work because it is his basic

philosophy and concepts that have influenced me, and these run through all of his work as well

as the work of so many others who have founded the field of group dynamics and organization

development. (Schein, 1996: 27)

This explanation of the unusual practice of writing an article about a theorist who has been

a great influence without making any references to his work, despite referencing the work

of others who have been less influential, encouraged us to look further. Most who write

about CATS, if they cite anything, cite ‘Lewin, 1951’, Field Theory in Social Science. This

is not a book written by Lewin but an ‘edited compilation of his scattered papers’ (Shea,

1951: 65) published four years after his death in 1947. Field Theory was edited by Dorwin

Cartwright as a second companion volume to an earlier collection of Lewin’s works com-

piled by Kurt Lewin’s widow, with a foreword by Gordon Allport (Lewin, 1948).

36 Human Relations 69(1)

Normally in academic writing, providing a name and date reference without a page

number implies that the idea, example or concept referred to is a key aspect of the book

or article. Of the nearly 10,000 citations to ‘Lewin, 1951’ listed on Google Scholar,

none of the first 100 (that is, the most highly cited of those who cite Lewin), provides

a page reference. But despite this, mention of CATS in Field Theory is devilishly dif-

ficult to find. It is the subject of just two short paragraphs (131 words) in a 338 page

book (1951: 228). 1

As one reviewer of the day makes clear, Lewin 1951 contains ‘nothing, other than the

editor’s introduction, that has not been published before’ (Lindzey, 1952: 132). And the

fragment that would be developed into the CATS model is from an article published in

1947 titled ‘Frontiers in Group Dynamics’: the first article of the first issue of Human

Relations (Lewin, 1947a). It is buried there in the 24th of 25 sub-sections in a 37 page

article. Unlike the other points made in Field Theory or the 1947 article, no empirical

evidence is provided or graphical illustration given of CATS, and unlike Lewin’s other

writings, the idea is not well-integrated with other elements. It is merely described as a

way that ‘planned social change may be thought of’ (Lewin, 1947a: 36; 1951: 231); an

example explaining (in an abstract way) the group dynamics of social change and the

advantages of group versus individual decision making. It appears almost as an after-

thought, or at least not fully thought out, given that the metaphor of ‘unfreezing’ and

‘freezing’ seems to contradict Lewin’s more detailed empirically-based theorizing of

‘quasi-equilibrium’, which is explained in considerable depth in Field Theory and argues

that groups are in a continual process of adaptation, rather than a steady or frozen state.

Apart from these few words published in 1947 (a few months after Lewin’s death), we

could find no other provenance for CATS in his work, unusual for a man lauded for his

thorough experimentation and desire to base social psychology on firm empirical

foundations.

A book edited by Newcomb and Hartley contains a chapter claimed to be ‘one of the

last articles to come from the pen of Kurt Lewin’ (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947: v). It

combines some ideas from the Human Relations article but gives a little more promi-

nence to CATS, labelling it a ‘Three-Step Procedure’ and attempting to link it to some

empirical evidence. However, this evidence seems completely disconnected from the

‘procedure’. The chapter begins (Lewin, 1947b: 330) by explaining that: ‘The following

experiments on group decision have been conducted during the last four years. They are

not in a state that permits definite conclusions’. None of the other chapters is framed in

such a tentative manner. And the editors acknowledge that the book went to press after

Lewin’s death (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947). All of which suggests that Lewin may not

have had the chance to fully revise the paper or that elements might have been finished

by the editors.

Despite the lack of emphasis on CATS in Lewin’s own writing, the impression is that

Lewin gave great thought to CATS. Lewin’s recent defenders see CATS as one of his

four main ‘interrelated elements’ (Burnes and Cooke, 2012: 1397) that Lewin ‘saw . . .

as an interrelated whole’ (Burnes, 2004a: 981); or one of ‘Lewin’s four elements’ (Edward

and Montessori, 2011: 8). But there seems no evidence for this. Having searched Lewin’s

publications written or translated into English (67 articles, book chapters and books), the

Normally in academic writing, providing a name and date reference without a page

number implies that the idea, example or concept referred to is a key aspect of the book

or article. Of the nearly 10,000 citations to ‘Lewin, 1951’ listed on Google Scholar,

none of the first 100 (that is, the most highly cited of those who cite Lewin), provides

a page reference. But despite this, mention of CATS in Field Theory is devilishly dif-

ficult to find. It is the subject of just two short paragraphs (131 words) in a 338 page

book (1951: 228). 1

As one reviewer of the day makes clear, Lewin 1951 contains ‘nothing, other than the

editor’s introduction, that has not been published before’ (Lindzey, 1952: 132). And the

fragment that would be developed into the CATS model is from an article published in

1947 titled ‘Frontiers in Group Dynamics’: the first article of the first issue of Human

Relations (Lewin, 1947a). It is buried there in the 24th of 25 sub-sections in a 37 page

article. Unlike the other points made in Field Theory or the 1947 article, no empirical

evidence is provided or graphical illustration given of CATS, and unlike Lewin’s other

writings, the idea is not well-integrated with other elements. It is merely described as a

way that ‘planned social change may be thought of’ (Lewin, 1947a: 36; 1951: 231); an

example explaining (in an abstract way) the group dynamics of social change and the

advantages of group versus individual decision making. It appears almost as an after-

thought, or at least not fully thought out, given that the metaphor of ‘unfreezing’ and

‘freezing’ seems to contradict Lewin’s more detailed empirically-based theorizing of

‘quasi-equilibrium’, which is explained in considerable depth in Field Theory and argues

that groups are in a continual process of adaptation, rather than a steady or frozen state.

Apart from these few words published in 1947 (a few months after Lewin’s death), we

could find no other provenance for CATS in his work, unusual for a man lauded for his

thorough experimentation and desire to base social psychology on firm empirical

foundations.

A book edited by Newcomb and Hartley contains a chapter claimed to be ‘one of the

last articles to come from the pen of Kurt Lewin’ (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947: v). It

combines some ideas from the Human Relations article but gives a little more promi-

nence to CATS, labelling it a ‘Three-Step Procedure’ and attempting to link it to some

empirical evidence. However, this evidence seems completely disconnected from the

‘procedure’. The chapter begins (Lewin, 1947b: 330) by explaining that: ‘The following

experiments on group decision have been conducted during the last four years. They are

not in a state that permits definite conclusions’. None of the other chapters is framed in

such a tentative manner. And the editors acknowledge that the book went to press after

Lewin’s death (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947). All of which suggests that Lewin may not

have had the chance to fully revise the paper or that elements might have been finished

by the editors.

Despite the lack of emphasis on CATS in Lewin’s own writing, the impression is that

Lewin gave great thought to CATS. Lewin’s recent defenders see CATS as one of his

four main ‘interrelated elements’ (Burnes and Cooke, 2012: 1397) that Lewin ‘saw . . .

as an interrelated whole’ (Burnes, 2004a: 981); or one of ‘Lewin’s four elements’ (Edward

and Montessori, 2011: 8). But there seems no evidence for this. Having searched Lewin’s

publications written or translated into English (67 articles, book chapters and books), the

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Cummings et al. 37

Lewin archives at the University of Iowa, and the archives at the Tavistock Institute in

London where Human Relations was based, we can find no other origin for CATS.

Moreover, CATS was not regarded as significant when Lewin was alive or even in the

period after his death. Tributes after Lewin’s death acknowledge many important contri-

butions, such as action research, field theory and his concept of topology. But Alfred

Marrow (1947) does not mention CATS, nor does Dennis Likert, in the same issue of

Human Relations in which Lewin’s 1947 article appears. Ronald Lippitt’s (1947) obitu-

ary reviews 10 major contributions and CATS is not one of them. None of the many

reviews of ‘Lewin, 1951’ mentions it as a significant contribution (e.g. Kuhn, 1951;

Lasswell, 1952; Lindzey, 1952; Shea, 1951; Smith, 1951), and neither does Cartwright’s

extensive introduction to the volume. Papers on the contribution of Lewin to manage-

ment thought presented by his daughter Miriam Lewin Papanek (1973) and William B

Wolf (1973) at the Academy of Management conference do not refer to CATS. Twenty-

two years after Marrow wrote his obituary, his 300-page biography of Lewin does make

brief mention of CATS as a way that Lewin had ‘considered the change process’ shortly

before his death, but notes that Lewin had ‘recognized that problems of inducing change

would require significantly more research than had yet been carried out’ (1969: 223).

Even a three volume retrospective on the Tavistock Institute, which refers extensively to

Lewin’s work and the way he inspired other researchers, is silent on CATS (Trist and

Murray, 1990, 1993; Trist et al., 1997).

A few writers cite Lewin’s chapter in Newcomb and Hartley when referring to CATS.

A significant number cite the 1947 Human Relations article. But far more cite ‘Field

Theory, 1951’. And it is unlikely that many who cite Lewin now read his words: a lack

of connection that may explain some interesting fictions. The most significant may be

the invention of the word ‘refreezing’ as the full-stop at the end of what would become

change management’s foundational framework – a term that implies that frozen is an

organization’s natural state until an agent intervenes and zaps it (as later textbooks pro-

moting Lewin’s ‘classic model’ would say ‘refreezing the new change makes it perma-

nent’, Robbins, 1991: 646).

Lewin never wrote ‘refreezing’ anywhere. As far as we can ascertain, the re-phrasing

of Lewin’s freezing to ‘refreezing’ happened first in a 1950 conference paper by Lewin’s

former student Leon Festinger (Festinger and Coyle, 1950; reprinted in Festinger, 1980:

14). Festinger said that: ‘To Lewin, life was not static; it was changing, dynamic, fluid.

Lewin’s unfreezing-stabilizing-refreezing concept of change continues to be highly rel-

evant today’. It is worth noting that Festinger’s first sentence seems to contradict the

second, or at least to contradict later interpretations of Lewin as the developer of a model

that deals in static, or at least clearly delineated, steps. Furthermore, Festinger misrepre-

sents other elements; Lewin’s ‘moving’ is transposed into ‘stabilizing’, which shows

how open to interpretation Lewin’s nascent thinking was in this ‘preparadigmatic’ period

(Becher and Trowler, 2001: 33).

Other disconnected interpretations include Stephen Covey noting the influence of

‘Kirk Lewin’ on his thinking about change (Covey, 2004: 325); and citations for articles

titled ‘The ABCs of change management’ and ‘Frontiers in group mechanics’, both

claimed to have been written by Lewin and published in 1947.2 On further investigation,

despite these articles being cited in respected academic books and articles (in Bidanda

Lewin archives at the University of Iowa, and the archives at the Tavistock Institute in

London where Human Relations was based, we can find no other origin for CATS.

Moreover, CATS was not regarded as significant when Lewin was alive or even in the

period after his death. Tributes after Lewin’s death acknowledge many important contri-

butions, such as action research, field theory and his concept of topology. But Alfred

Marrow (1947) does not mention CATS, nor does Dennis Likert, in the same issue of

Human Relations in which Lewin’s 1947 article appears. Ronald Lippitt’s (1947) obitu-

ary reviews 10 major contributions and CATS is not one of them. None of the many

reviews of ‘Lewin, 1951’ mentions it as a significant contribution (e.g. Kuhn, 1951;

Lasswell, 1952; Lindzey, 1952; Shea, 1951; Smith, 1951), and neither does Cartwright’s

extensive introduction to the volume. Papers on the contribution of Lewin to manage-

ment thought presented by his daughter Miriam Lewin Papanek (1973) and William B

Wolf (1973) at the Academy of Management conference do not refer to CATS. Twenty-

two years after Marrow wrote his obituary, his 300-page biography of Lewin does make

brief mention of CATS as a way that Lewin had ‘considered the change process’ shortly

before his death, but notes that Lewin had ‘recognized that problems of inducing change

would require significantly more research than had yet been carried out’ (1969: 223).

Even a three volume retrospective on the Tavistock Institute, which refers extensively to

Lewin’s work and the way he inspired other researchers, is silent on CATS (Trist and

Murray, 1990, 1993; Trist et al., 1997).

A few writers cite Lewin’s chapter in Newcomb and Hartley when referring to CATS.

A significant number cite the 1947 Human Relations article. But far more cite ‘Field

Theory, 1951’. And it is unlikely that many who cite Lewin now read his words: a lack

of connection that may explain some interesting fictions. The most significant may be

the invention of the word ‘refreezing’ as the full-stop at the end of what would become

change management’s foundational framework – a term that implies that frozen is an

organization’s natural state until an agent intervenes and zaps it (as later textbooks pro-

moting Lewin’s ‘classic model’ would say ‘refreezing the new change makes it perma-

nent’, Robbins, 1991: 646).

Lewin never wrote ‘refreezing’ anywhere. As far as we can ascertain, the re-phrasing

of Lewin’s freezing to ‘refreezing’ happened first in a 1950 conference paper by Lewin’s

former student Leon Festinger (Festinger and Coyle, 1950; reprinted in Festinger, 1980:

14). Festinger said that: ‘To Lewin, life was not static; it was changing, dynamic, fluid.

Lewin’s unfreezing-stabilizing-refreezing concept of change continues to be highly rel-

evant today’. It is worth noting that Festinger’s first sentence seems to contradict the

second, or at least to contradict later interpretations of Lewin as the developer of a model

that deals in static, or at least clearly delineated, steps. Furthermore, Festinger misrepre-

sents other elements; Lewin’s ‘moving’ is transposed into ‘stabilizing’, which shows

how open to interpretation Lewin’s nascent thinking was in this ‘preparadigmatic’ period

(Becher and Trowler, 2001: 33).

Other disconnected interpretations include Stephen Covey noting the influence of

‘Kirk Lewin’ on his thinking about change (Covey, 2004: 325); and citations for articles

titled ‘The ABCs of change management’ and ‘Frontiers in group mechanics’, both

claimed to have been written by Lewin and published in 1947.2 On further investigation,

despite these articles being cited in respected academic books and articles (in Bidanda

38 Human Relations 69(1)

et al., 1999: 417; Kraft et al., 2008, 2009) and sounding like something the modern con-

ception of change management’s founding father might have written (anyone simple

enough to reduce all change to an ice cube might write about change being as easy or

mechanical as ABC), they do not actually exist.

As noted earlier, scholars like Clegg et al. (2005: 376) and Child (2005: 293) have

critiqued Lewin’s work for being too simple or mechanistic for modern environments or

unable to ‘represent the reality of change’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570). Indeed, in

recent years this has become something of a chorus, with a number of writers (e.g.

Palmer and Dunford, 2008; Stacey, 2007; Weick and Quinn, 1999) associating ‘classical

“episodic” views’ (Badham et al., 2012: 189) or ‘stage models, such as Lewin’s (1951)

classic’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570) with the ‘classical Lewinian unfreeze-movement-

refreeze formula, which had guided OD work from its inception’, but which was now

inappropriate ‘for the rapid pace of change at the beginning of the 21st century’ (Marshak

and Heracleous, 2004: 1051).

However, once again these prosecutions seem unrelated to what Lewin actually wrote.

Lewin never presented CATS in a linear diagrammatic form and he did not list it as bullet

points. Lewin was adamant that group dynamics must not be seen in simplistic or static

terms and believed that groups were never in a steady state, seeing them instead as being

in continuous movement, albeit having periods of relative stability or ‘quasi-stationary

equilibria’ (1951: 199). Lewin never wrote his idea was a model that could be used by a

change agent. He did, however, do significant research and re-published highly respected

articles that argued against Taylor’s mechanistic approach (Lewin, 1920; Marrow, 1969).

Perhaps the view of Lewin as a simplistic thinker emerges from his re-presentation

later in management textbooks, where the major output of his life-work appears to be a

rudimentary three-step model developed as a guide for managerial interventions. But it

is hard to imagine that anybody with Lewin’s background would hold such a simplisti-

cally ordered world-view. He studied philosophy and psychology. He worked at the

Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin until 1933 and devoted himself to

establishing a Psychological Institute at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem after leav-

ing the growing anti-Semitic chaos of Germany. His first major article contrasted

Aristotle and Galileo (Lewin, 1931), and ‘undoubtedly one of the last pieces of such

creative work from the pen of Kurt Lewin . . . mailed to the editor on January 3rd, 1947’

(Schilpp, 1949: xvi–xvii), was a piece on the philosophy of Ernst Cassirer (Lewin, 1949).

Lewin fled to the USA in 1933 to the School of Home Economics at Cornell University

where he studied the behaviour of children. From 1935 to 1945 he was at the Iowa Child

Welfare Research Station at the University of Iowa. While in Iowa, Lewin listed his title

as ‘Professor of Child Psychology’. But despite a highly dexterous mind and growing up

amid real chaos and change, he is demeaned by modern texts that smugly claim that his

CATS ‘has become obsolete [because] it applies to a world of certainty and predictability

[where it] was developed. [I]t reflects the environment of those times [which] has little

resemblance to today’s environment of constant and chaotic change’ (Robbins and Judge,

2009: 625–628).

To summarize, CATS is claimed to be one of Lewin’s most important pieces of

work, a cornerstone, which it was not. Lewin is claimed to have developed a three-step

et al., 1999: 417; Kraft et al., 2008, 2009) and sounding like something the modern con-

ception of change management’s founding father might have written (anyone simple

enough to reduce all change to an ice cube might write about change being as easy or

mechanical as ABC), they do not actually exist.

As noted earlier, scholars like Clegg et al. (2005: 376) and Child (2005: 293) have

critiqued Lewin’s work for being too simple or mechanistic for modern environments or

unable to ‘represent the reality of change’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570). Indeed, in

recent years this has become something of a chorus, with a number of writers (e.g.

Palmer and Dunford, 2008; Stacey, 2007; Weick and Quinn, 1999) associating ‘classical

“episodic” views’ (Badham et al., 2012: 189) or ‘stage models, such as Lewin’s (1951)

classic’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570) with the ‘classical Lewinian unfreeze-movement-

refreeze formula, which had guided OD work from its inception’, but which was now

inappropriate ‘for the rapid pace of change at the beginning of the 21st century’ (Marshak

and Heracleous, 2004: 1051).

However, once again these prosecutions seem unrelated to what Lewin actually wrote.

Lewin never presented CATS in a linear diagrammatic form and he did not list it as bullet

points. Lewin was adamant that group dynamics must not be seen in simplistic or static

terms and believed that groups were never in a steady state, seeing them instead as being

in continuous movement, albeit having periods of relative stability or ‘quasi-stationary

equilibria’ (1951: 199). Lewin never wrote his idea was a model that could be used by a

change agent. He did, however, do significant research and re-published highly respected

articles that argued against Taylor’s mechanistic approach (Lewin, 1920; Marrow, 1969).

Perhaps the view of Lewin as a simplistic thinker emerges from his re-presentation

later in management textbooks, where the major output of his life-work appears to be a

rudimentary three-step model developed as a guide for managerial interventions. But it

is hard to imagine that anybody with Lewin’s background would hold such a simplisti-

cally ordered world-view. He studied philosophy and psychology. He worked at the

Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin until 1933 and devoted himself to

establishing a Psychological Institute at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem after leav-

ing the growing anti-Semitic chaos of Germany. His first major article contrasted

Aristotle and Galileo (Lewin, 1931), and ‘undoubtedly one of the last pieces of such

creative work from the pen of Kurt Lewin . . . mailed to the editor on January 3rd, 1947’

(Schilpp, 1949: xvi–xvii), was a piece on the philosophy of Ernst Cassirer (Lewin, 1949).

Lewin fled to the USA in 1933 to the School of Home Economics at Cornell University

where he studied the behaviour of children. From 1935 to 1945 he was at the Iowa Child

Welfare Research Station at the University of Iowa. While in Iowa, Lewin listed his title

as ‘Professor of Child Psychology’. But despite a highly dexterous mind and growing up

amid real chaos and change, he is demeaned by modern texts that smugly claim that his

CATS ‘has become obsolete [because] it applies to a world of certainty and predictability

[where it] was developed. [I]t reflects the environment of those times [which] has little

resemblance to today’s environment of constant and chaotic change’ (Robbins and Judge,

2009: 625–628).

To summarize, CATS is claimed to be one of Lewin’s most important pieces of

work, a cornerstone, which it was not. Lewin is claimed to have developed a three-step

Cummings et al. 39

model to guide change agents, which he did not. Lewin is assumed to have given us

unfreeze-change-refreeze, which is only 33 percent right (he only wrote unfreeze).

Lewin is consequently dismissed as a simpleton, which is clearly not the case. In light

of these anomalies, we sought to investigate how Lewin’s CATS developed into such

a seminal foundation.

Our initial thinking was that Lewin and CATS may fulfil a role in the formation of

change management similar to that played by Aristotle’s theories in the history of

Psychology (Richards, 1996; Smith, 1988). The work of Michel Foucault has been uti-

lized to explore this phenomenon of how fledgling fields seek to establish themselves

and gain from showing a connection to, and growth beyond, a great man of philosophy

or science. Other studies that have sought to critically examine assumed intellectual

foundations of fields related to change management have utilized the approaches of

Michel Foucault to highlight such foundational developments (e.g. Cummings and

Bridgman, 2011, on Organization Theory; Garel, 2013, on Project Management; Wilson,

2013, on Leadership), and we sought to do likewise in this instance. Foucault has also

been used to analyse the ‘canonization’ of Lewin’s legacy, the view that planned change

can be managed in a linear fashion, and the notion of the change agent as a rational and

neutral actor (Caldwell, 2005, 2006). While we share an interest in critiquing mainstream

approaches to change management and Lewin’s hagiography and misrepresentation

(Burnes, 2004a, 2004b; Burnes and Cooke, 2012, 2013), our particular objective is to

analyse the movement, formation and reproduction of CATS’s form as a foundation of

our thinking about change management.

The counter-historical approaches of Michel Foucault and

exploring the career of an idea

The careers of ideas are sometimes influenced as much by their reception as their initial

articulation. (James A Ogilvy, Many Dimensional Man, 1977: i)

Michel Foucault’s work (1980: 70) sought to counter conventional histories that pre-

sented a ‘progress of consciousness’ leading to our present ‘advanced’ state: histories

that legitimated the current establishment. Foucault instead examined ‘the emergence of

[an established field’s] truth games’. Thus, against histories that traced psychology’s

uncovering of the truth about madness, Foucault (1965: 142) highlighted the role of psy-

chology’s history in presenting psychology as at once building on noble foundations

(Socrates, Aristotle) while innovating to bring forth a new ‘happy age in which madness

was at last recognized and treated in accordance with a truth to which we had long

remained blind’. Foucault claimed that this history was not objective but written as antic-

ipation: the past viewed in terms of making sense of the present’s great ‘heights’.

What sustains our belief in what we subsequently take to be as advances in knowledge

built upon these foundations? Foucault’s answer was a power network ‘of relations, con-

stantly in tension, in activity’ (Foucault, 1977a: 26). These networks grow as texts and

surrounding discourse educates initiates by reduplicating and re-interpreting events and

assumptions taken to be important. Conventional histories contribute further to these

production/repression networks as they connect disparate events and interpretations into

model to guide change agents, which he did not. Lewin is assumed to have given us

unfreeze-change-refreeze, which is only 33 percent right (he only wrote unfreeze).

Lewin is consequently dismissed as a simpleton, which is clearly not the case. In light

of these anomalies, we sought to investigate how Lewin’s CATS developed into such

a seminal foundation.

Our initial thinking was that Lewin and CATS may fulfil a role in the formation of

change management similar to that played by Aristotle’s theories in the history of

Psychology (Richards, 1996; Smith, 1988). The work of Michel Foucault has been uti-

lized to explore this phenomenon of how fledgling fields seek to establish themselves

and gain from showing a connection to, and growth beyond, a great man of philosophy

or science. Other studies that have sought to critically examine assumed intellectual

foundations of fields related to change management have utilized the approaches of

Michel Foucault to highlight such foundational developments (e.g. Cummings and

Bridgman, 2011, on Organization Theory; Garel, 2013, on Project Management; Wilson,

2013, on Leadership), and we sought to do likewise in this instance. Foucault has also

been used to analyse the ‘canonization’ of Lewin’s legacy, the view that planned change

can be managed in a linear fashion, and the notion of the change agent as a rational and

neutral actor (Caldwell, 2005, 2006). While we share an interest in critiquing mainstream

approaches to change management and Lewin’s hagiography and misrepresentation

(Burnes, 2004a, 2004b; Burnes and Cooke, 2012, 2013), our particular objective is to

analyse the movement, formation and reproduction of CATS’s form as a foundation of

our thinking about change management.

The counter-historical approaches of Michel Foucault and

exploring the career of an idea

The careers of ideas are sometimes influenced as much by their reception as their initial

articulation. (James A Ogilvy, Many Dimensional Man, 1977: i)

Michel Foucault’s work (1980: 70) sought to counter conventional histories that pre-

sented a ‘progress of consciousness’ leading to our present ‘advanced’ state: histories

that legitimated the current establishment. Foucault instead examined ‘the emergence of

[an established field’s] truth games’. Thus, against histories that traced psychology’s

uncovering of the truth about madness, Foucault (1965: 142) highlighted the role of psy-

chology’s history in presenting psychology as at once building on noble foundations

(Socrates, Aristotle) while innovating to bring forth a new ‘happy age in which madness

was at last recognized and treated in accordance with a truth to which we had long

remained blind’. Foucault claimed that this history was not objective but written as antic-

ipation: the past viewed in terms of making sense of the present’s great ‘heights’.

What sustains our belief in what we subsequently take to be as advances in knowledge

built upon these foundations? Foucault’s answer was a power network ‘of relations, con-

stantly in tension, in activity’ (Foucault, 1977a: 26). These networks grow as texts and

surrounding discourse educates initiates by reduplicating and re-interpreting events and

assumptions taken to be important. Conventional histories contribute further to these

production/repression networks as they connect disparate events and interpretations into

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

40 Human Relations 69(1)

a continuum to show that the present rests upon grand origins, profound intentions and

immutable necessities, and, in a circular manner, these identified origins become ‘the site

of truth that makes possible a field of knowledge whose function is to recover it’

(Foucault, 1977b: 144). But while such networks ‘perpetually create knowledge’ by pro-

ducing ‘domains of objects and rituals of truth’, they also repress by concealing other

possibilities (Foucault, 1980: 52, 194). Subsequently, Foucault defined his overarching

counter-historical aim as raising doubt about what was promoted as the truth of the foun-

dation and evolution of objects in order to ‘free thought from what it silently thinks, and

so enable it to think differently’ (Foucault, 1985: 9; also Foucault, 1977b: 154; Dreyfus

and Rabinow, 1983: 120).

Foucault developed many approaches for developing such counter-histories. However,

to analyse the formation of CATS into the form we recognize today we utilize a particu-

lar perspective developed by Richard Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (1983) in discussion

with Foucault: interpretive analytics (IA). IA combined Foucault’s interest in what he

called archaeology and genealogy. Archaeology studied the effects of episteme, an

archaeological strata or: ‘world-view[s] . . . which imposes . . . norms and postulates, a

general stage of reason [and] a certain structure of thought’ (Foucault, 1976: 191) on the

development of knowledge objects; the ‘conditions of possibility’ for acceptable knowl-

edge at particular times (Foucault, 1970: xxii). Genealogy, on the other hand, traced the

networks of relations that procreated knowledge’s formation over time. The archaeologi-

cal side of IA ‘deals with the system’s enveloping discourse . . . The genealogical side of

analysis, by way of contrast, deals with series of effective formation of discourse

(Foucault, in Dreyfus and Rabinow 1983: 105; see also Foucault, 1985: 12).

Initiates to the sub-field of change management are generally shown a progress of

consciousness that begins with CATS as a key foundation, the first and now ‘classic’

theory, and culminates in the current ‘state of the art’. Our counter-history aims to

‘unfreeze’ CATS, to show how it takes form and develops into something far more than

its author ever intended. We examine how its author moves from a minor figure, into a

grand founder whose application of science enabled the discovery of the fundamentals of

change management, to the well-meaning simpleton who must be improved upon. We

follow the formation of the elements after Lewin’s death that would influence our view

of CATS as a foundational model for the problematization of change that spiked in the

1980s. Then we explore the episteme particular to the 1980s that made possible the form

of a new truth of CATS that we see in today. Beyond this, we analyse the reduplication,

continued formation and hardening of the historical view of CATS and its author beyond

the 1980s, and the development and continuity of many of the questionable interpreta-

tions that help maintain today’s belief in CATS as a noble, necessary, but overly simplis-

tic foundation upon which we have built but moved beyond.

In so doing, we find that CATS develops a life and career of its own that follows the

patterns outlined by other researchers who have taken a critical perspective on the

dynamics of disciplines: how preparadigmatic disciplines allow for greater diversity of

inputs and interpretations (Becher and Trowler, 2001); the quick ‘fractal’ splitting of

management into sub-fields each with their own distinct but related history as the space

afforded to business studies opens up (Abbott, 2001: 10); how particular competing con-

ceptions win out over others and gradually conceal them from view (Abbott, 2001); how

a continuum to show that the present rests upon grand origins, profound intentions and

immutable necessities, and, in a circular manner, these identified origins become ‘the site

of truth that makes possible a field of knowledge whose function is to recover it’

(Foucault, 1977b: 144). But while such networks ‘perpetually create knowledge’ by pro-

ducing ‘domains of objects and rituals of truth’, they also repress by concealing other

possibilities (Foucault, 1980: 52, 194). Subsequently, Foucault defined his overarching

counter-historical aim as raising doubt about what was promoted as the truth of the foun-

dation and evolution of objects in order to ‘free thought from what it silently thinks, and

so enable it to think differently’ (Foucault, 1985: 9; also Foucault, 1977b: 154; Dreyfus

and Rabinow, 1983: 120).

Foucault developed many approaches for developing such counter-histories. However,

to analyse the formation of CATS into the form we recognize today we utilize a particu-

lar perspective developed by Richard Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (1983) in discussion

with Foucault: interpretive analytics (IA). IA combined Foucault’s interest in what he

called archaeology and genealogy. Archaeology studied the effects of episteme, an

archaeological strata or: ‘world-view[s] . . . which imposes . . . norms and postulates, a

general stage of reason [and] a certain structure of thought’ (Foucault, 1976: 191) on the

development of knowledge objects; the ‘conditions of possibility’ for acceptable knowl-

edge at particular times (Foucault, 1970: xxii). Genealogy, on the other hand, traced the

networks of relations that procreated knowledge’s formation over time. The archaeologi-

cal side of IA ‘deals with the system’s enveloping discourse . . . The genealogical side of

analysis, by way of contrast, deals with series of effective formation of discourse

(Foucault, in Dreyfus and Rabinow 1983: 105; see also Foucault, 1985: 12).

Initiates to the sub-field of change management are generally shown a progress of

consciousness that begins with CATS as a key foundation, the first and now ‘classic’

theory, and culminates in the current ‘state of the art’. Our counter-history aims to

‘unfreeze’ CATS, to show how it takes form and develops into something far more than

its author ever intended. We examine how its author moves from a minor figure, into a

grand founder whose application of science enabled the discovery of the fundamentals of

change management, to the well-meaning simpleton who must be improved upon. We

follow the formation of the elements after Lewin’s death that would influence our view

of CATS as a foundational model for the problematization of change that spiked in the

1980s. Then we explore the episteme particular to the 1980s that made possible the form

of a new truth of CATS that we see in today. Beyond this, we analyse the reduplication,

continued formation and hardening of the historical view of CATS and its author beyond

the 1980s, and the development and continuity of many of the questionable interpreta-

tions that help maintain today’s belief in CATS as a noble, necessary, but overly simplis-

tic foundation upon which we have built but moved beyond.

In so doing, we find that CATS develops a life and career of its own that follows the

patterns outlined by other researchers who have taken a critical perspective on the

dynamics of disciplines: how preparadigmatic disciplines allow for greater diversity of

inputs and interpretations (Becher and Trowler, 2001); the quick ‘fractal’ splitting of

management into sub-fields each with their own distinct but related history as the space

afforded to business studies opens up (Abbott, 2001: 10); how particular competing con-

ceptions win out over others and gradually conceal them from view (Abbott, 2001); how

Cummings et al. 41

this fast growth facilitates exponential reduplication of winning frameworks (Whitley,

1984); and how in this process fields seek to generate, in somewhat contradictory fash-

ion, innovations that comply with collectively agreed concepts (Whitley, 1984). In con-

clusion, having outlined the evolution of CATS into the foundation upon which much

else in the sub-field builds, we step back behind that 1980s episteme to when change

management’s foundations could have been thought differently, in order to offer alterna-

tive historical pathways and futures for the field today.

The formation and form of CATS

Kurt Lewin introduced two ideas about change that have been very influential since the 1940s

. . . [one] was a model of the change process . . . unfreezing the old behavior; moving to a new

level of behavior; and refreezing the behavior at the new level. (What the 5th [1990: 81] edition

of Organizational Development by French and Bell records about Lewin and CATS).

‘ ’(What the early [1973–1983] editions of Organizational Development record about Lewin

and CATS [i.e. nothing]).

Genealogical formation

Prior to the early 1980s, Lewin’s CATS was largely unseen; by the end of the 1980s,

despite the fact that its form was anomalous to what Lewin actually wrote or likely

intended for the idea, it was the basis of our understanding of a fast growing field: change

management. The early seeds of this formation may be discerned in the reception

afforded CATS in the work of two key interpreters in the small but growing field of man-

agement studies: Ronald Lippitt and Edgar Schein in the 1950s and 1960s.

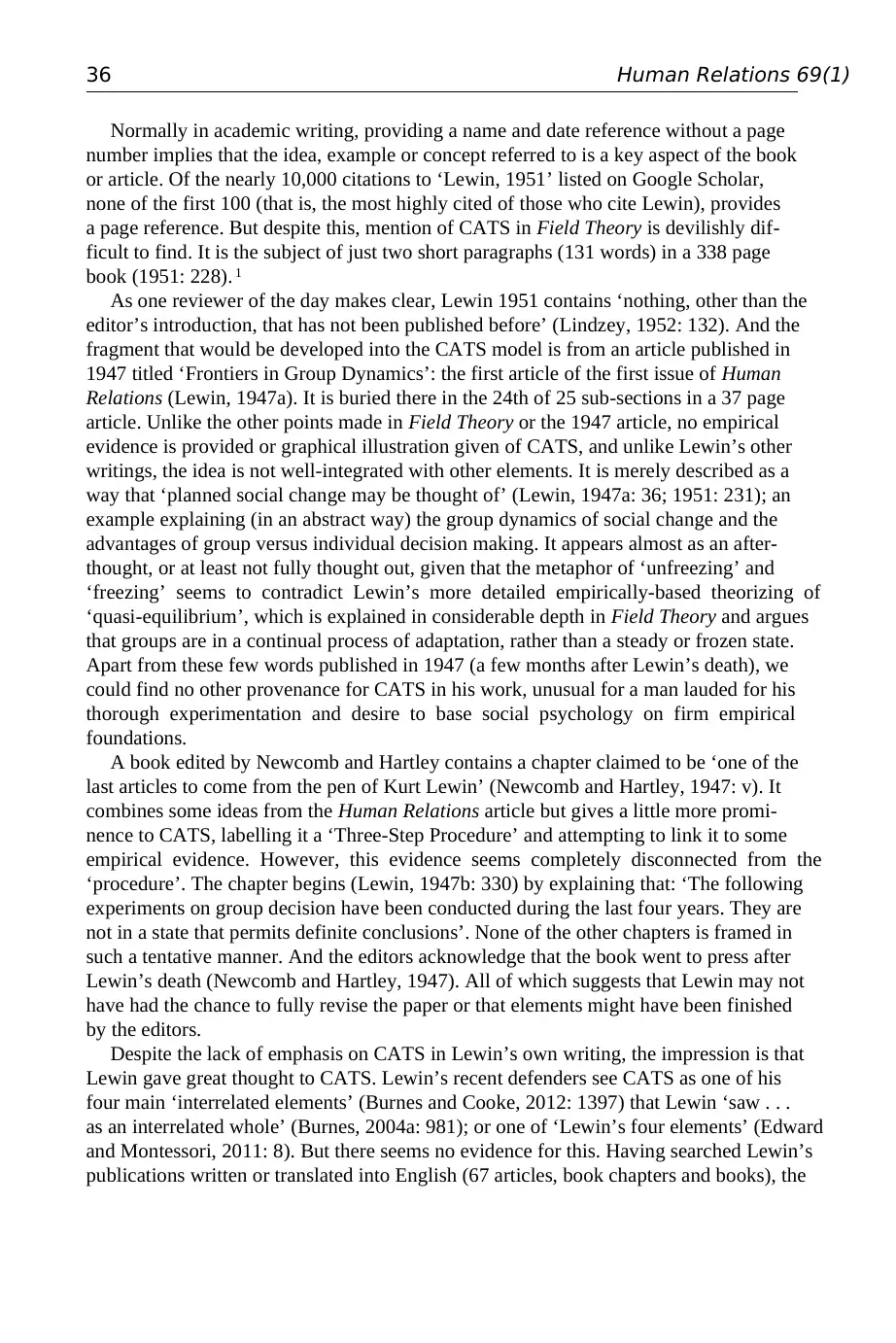

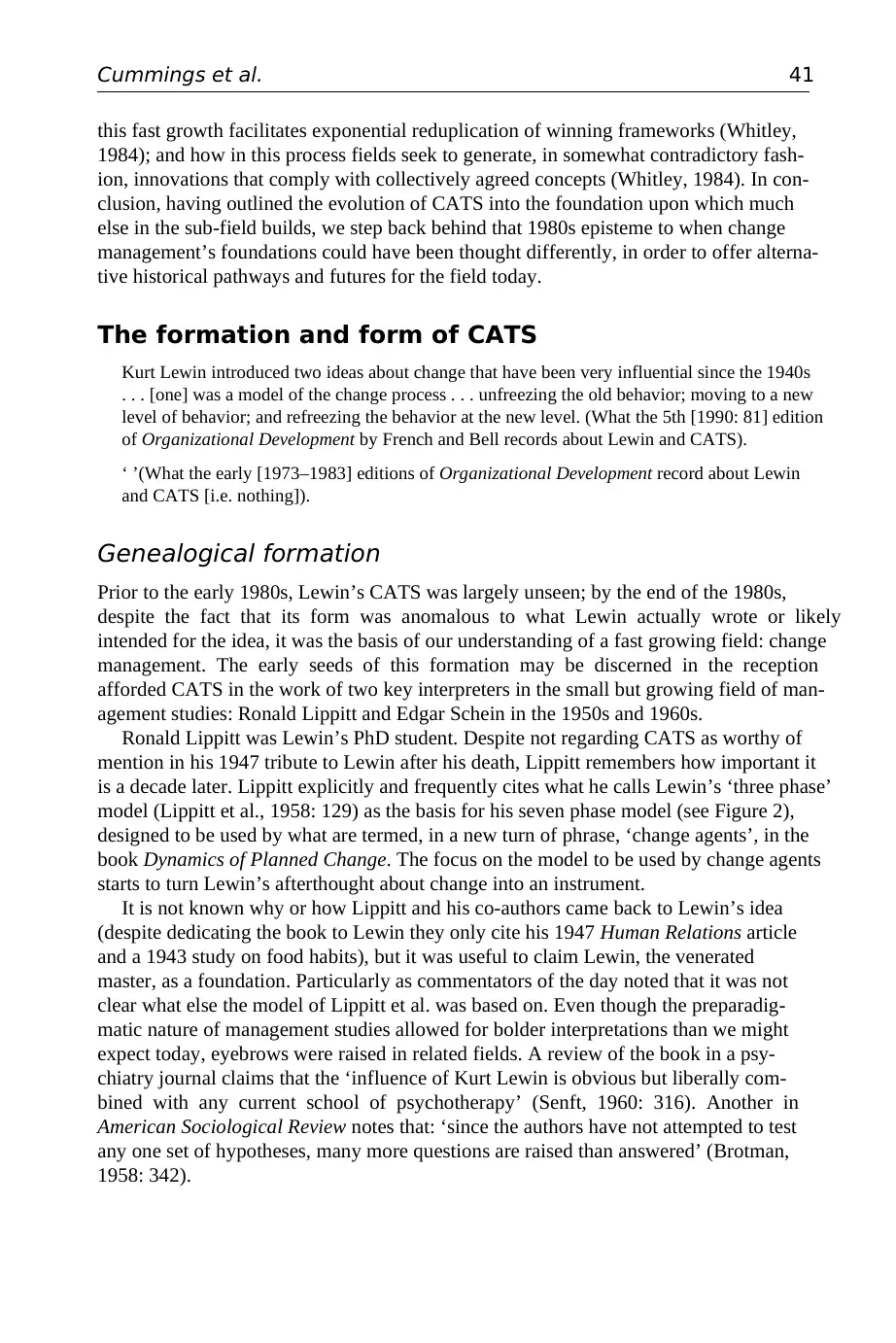

Ronald Lippitt was Lewin’s PhD student. Despite not regarding CATS as worthy of

mention in his 1947 tribute to Lewin after his death, Lippitt remembers how important it

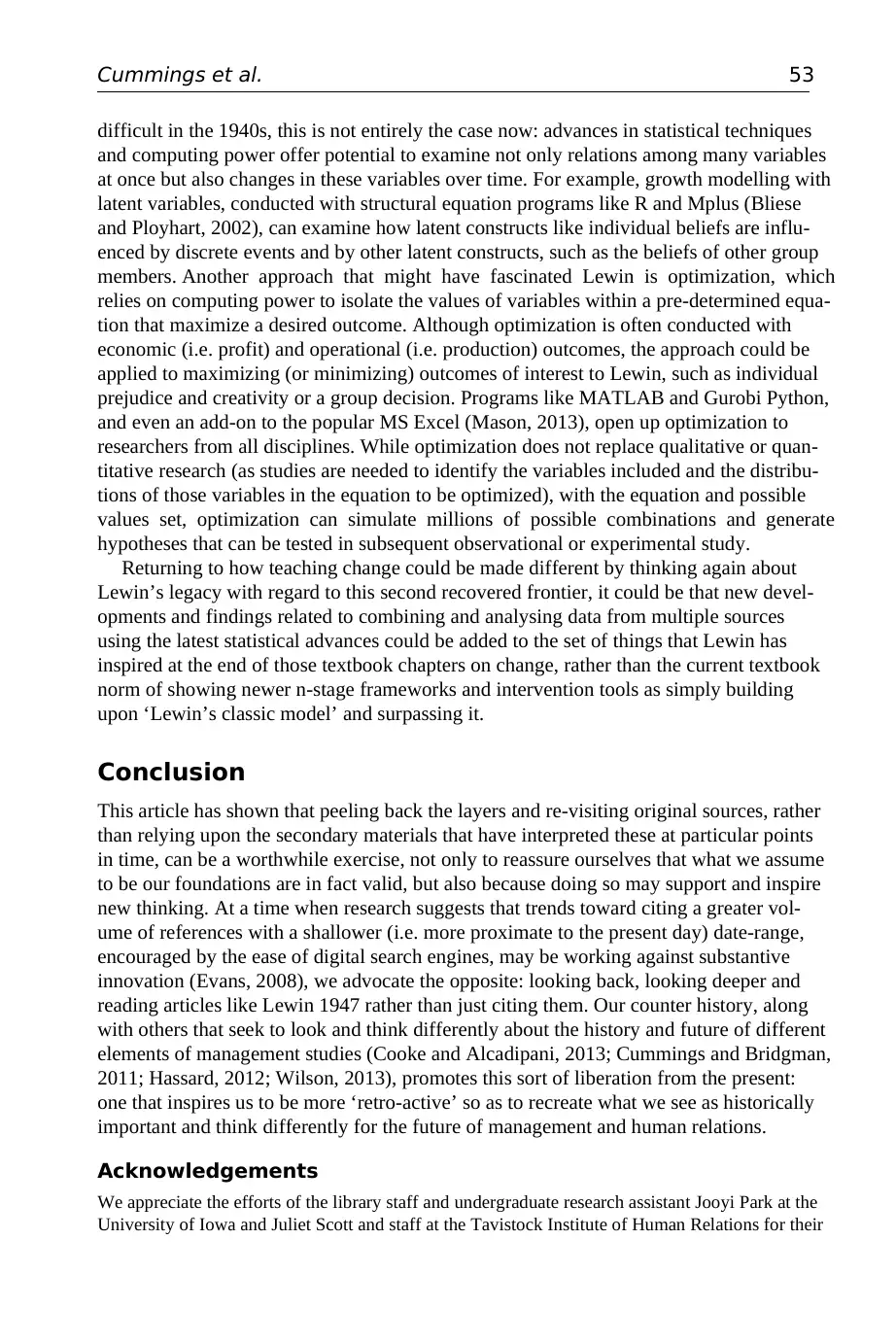

is a decade later. Lippitt explicitly and frequently cites what he calls Lewin’s ‘three phase’

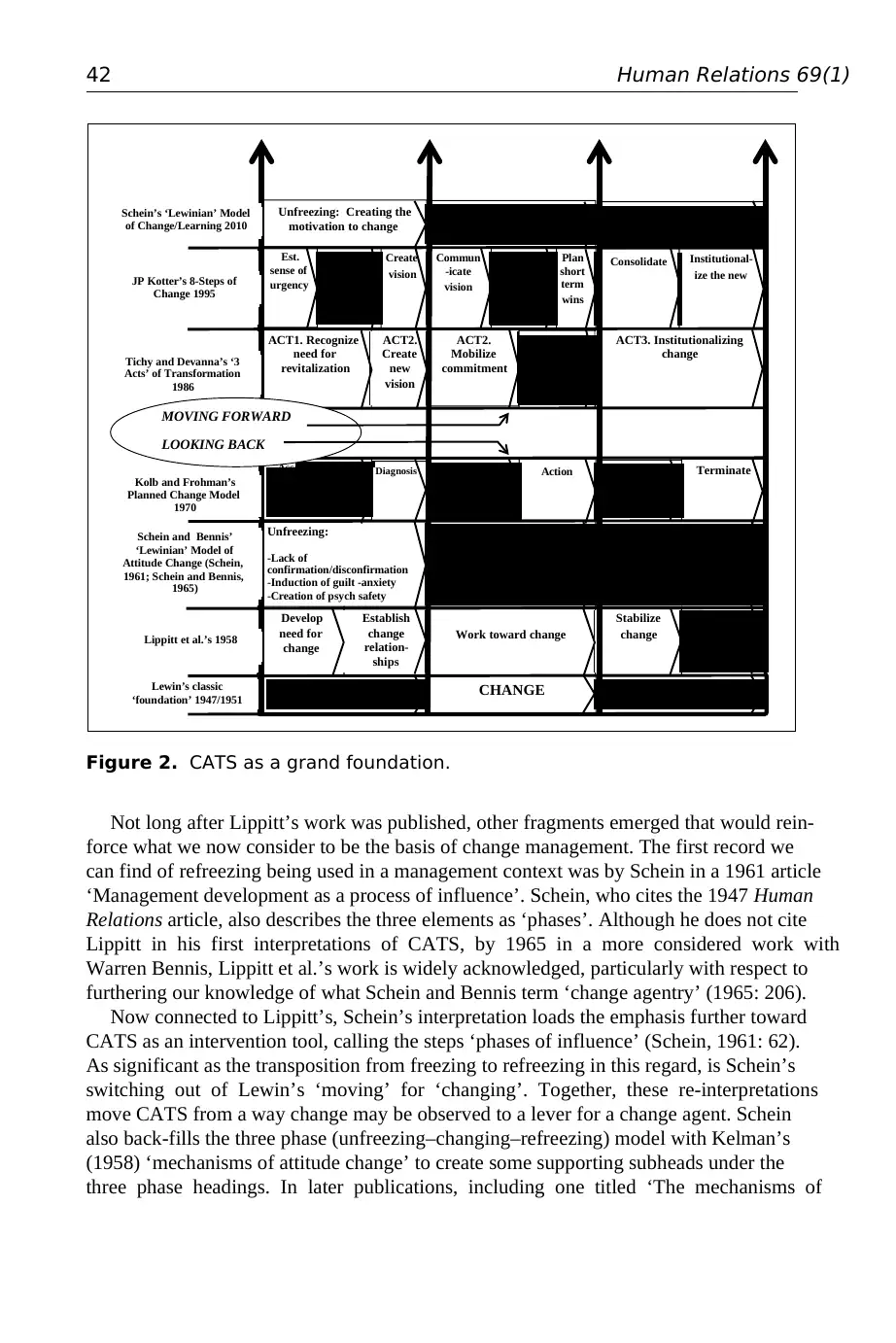

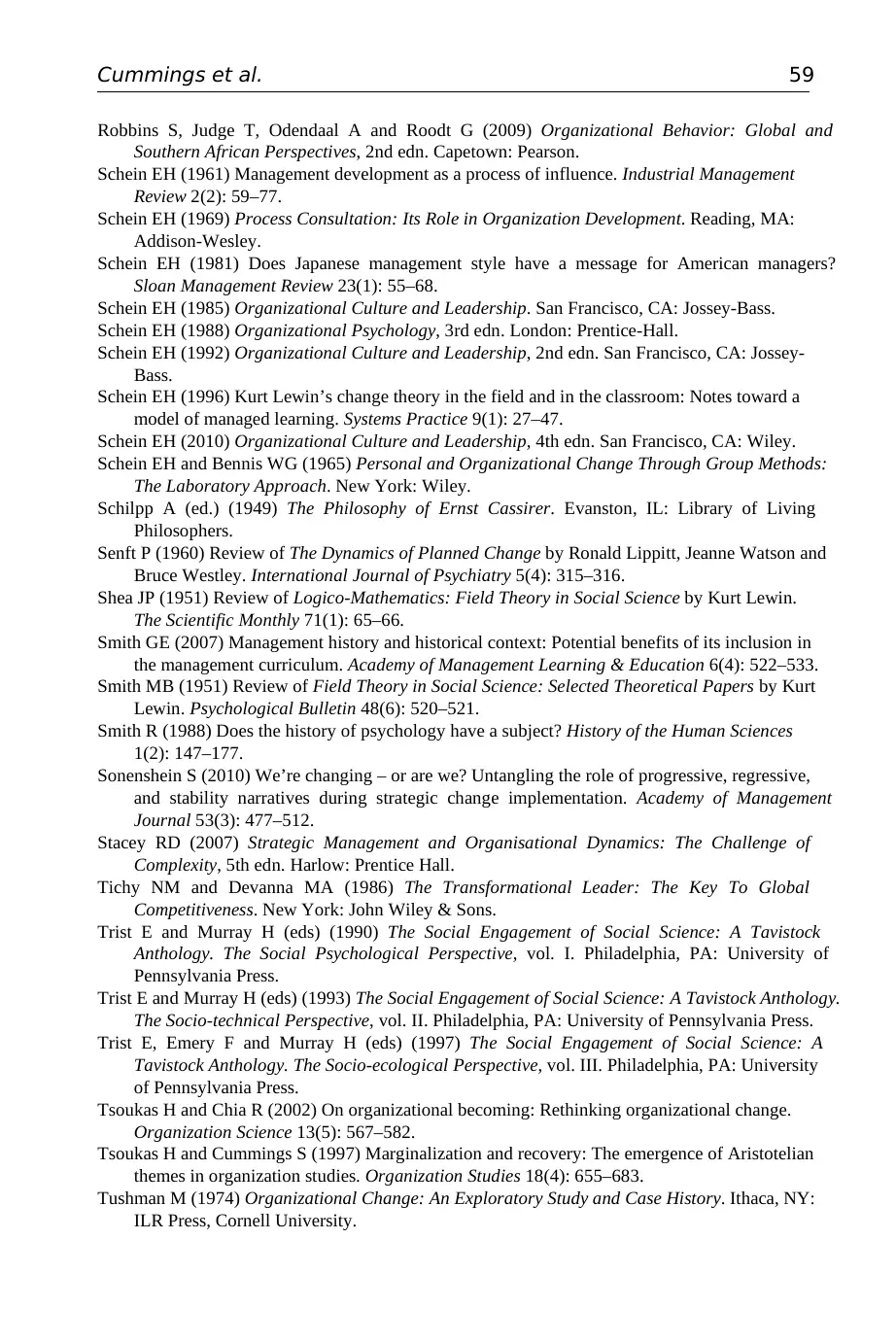

model (Lippitt et al., 1958: 129) as the basis for his seven phase model (see Figure 2),

designed to be used by what are termed, in a new turn of phrase, ‘change agents’, in the

book Dynamics of Planned Change. The focus on the model to be used by change agents

starts to turn Lewin’s afterthought about change into an instrument.

It is not known why or how Lippitt and his co-authors came back to Lewin’s idea

(despite dedicating the book to Lewin they only cite his 1947 Human Relations article

and a 1943 study on food habits), but it was useful to claim Lewin, the venerated

master, as a foundation. Particularly as commentators of the day noted that it was not

clear what else the model of Lippitt et al. was based on. Even though the preparadig-

matic nature of management studies allowed for bolder interpretations than we might

expect today, eyebrows were raised in related fields. A review of the book in a psy-

chiatry journal claims that the ‘influence of Kurt Lewin is obvious but liberally com-

bined with any current school of psychotherapy’ (Senft, 1960: 316). Another in

American Sociological Review notes that: ‘since the authors have not attempted to test

any one set of hypotheses, many more questions are raised than answered’ (Brotman,

1958: 342).

this fast growth facilitates exponential reduplication of winning frameworks (Whitley,

1984); and how in this process fields seek to generate, in somewhat contradictory fash-

ion, innovations that comply with collectively agreed concepts (Whitley, 1984). In con-

clusion, having outlined the evolution of CATS into the foundation upon which much

else in the sub-field builds, we step back behind that 1980s episteme to when change

management’s foundations could have been thought differently, in order to offer alterna-

tive historical pathways and futures for the field today.

The formation and form of CATS

Kurt Lewin introduced two ideas about change that have been very influential since the 1940s

. . . [one] was a model of the change process . . . unfreezing the old behavior; moving to a new

level of behavior; and refreezing the behavior at the new level. (What the 5th [1990: 81] edition

of Organizational Development by French and Bell records about Lewin and CATS).

‘ ’(What the early [1973–1983] editions of Organizational Development record about Lewin

and CATS [i.e. nothing]).

Genealogical formation

Prior to the early 1980s, Lewin’s CATS was largely unseen; by the end of the 1980s,

despite the fact that its form was anomalous to what Lewin actually wrote or likely

intended for the idea, it was the basis of our understanding of a fast growing field: change

management. The early seeds of this formation may be discerned in the reception

afforded CATS in the work of two key interpreters in the small but growing field of man-

agement studies: Ronald Lippitt and Edgar Schein in the 1950s and 1960s.

Ronald Lippitt was Lewin’s PhD student. Despite not regarding CATS as worthy of

mention in his 1947 tribute to Lewin after his death, Lippitt remembers how important it

is a decade later. Lippitt explicitly and frequently cites what he calls Lewin’s ‘three phase’

model (Lippitt et al., 1958: 129) as the basis for his seven phase model (see Figure 2),

designed to be used by what are termed, in a new turn of phrase, ‘change agents’, in the

book Dynamics of Planned Change. The focus on the model to be used by change agents

starts to turn Lewin’s afterthought about change into an instrument.

It is not known why or how Lippitt and his co-authors came back to Lewin’s idea

(despite dedicating the book to Lewin they only cite his 1947 Human Relations article

and a 1943 study on food habits), but it was useful to claim Lewin, the venerated

master, as a foundation. Particularly as commentators of the day noted that it was not

clear what else the model of Lippitt et al. was based on. Even though the preparadig-

matic nature of management studies allowed for bolder interpretations than we might

expect today, eyebrows were raised in related fields. A review of the book in a psy-

chiatry journal claims that the ‘influence of Kurt Lewin is obvious but liberally com-

bined with any current school of psychotherapy’ (Senft, 1960: 316). Another in

American Sociological Review notes that: ‘since the authors have not attempted to test

any one set of hypotheses, many more questions are raised than answered’ (Brotman,

1958: 342).

42 Human Relations 69(1)

Not long after Lippitt’s work was published, other fragments emerged that would rein-

force what we now consider to be the basis of change management. The first record we

can find of refreezing being used in a management context was by Schein in a 1961 article

‘Management development as a process of influence’. Schein, who cites the 1947 Human

Relations article, also describes the three elements as ‘phases’. Although he does not cite

Lippitt in his first interpretations of CATS, by 1965 in a more considered work with

Warren Bennis, Lippitt et al.’s work is widely acknowledged, particularly with respect to

furthering our knowledge of what Schein and Bennis term ‘change agentry’ (1965: 206).

Now connected to Lippitt’s, Schein’s interpretation loads the emphasis further toward

CATS as an intervention tool, calling the steps ‘phases of influence’ (Schein, 1961: 62).

As significant as the transposition from freezing to refreezing in this regard, is Schein’s

switching out of Lewin’s ‘moving’ for ‘changing’. Together, these re-interpretations

move CATS from a way change may be observed to a lever for a change agent. Schein

also back-fills the three phase (unfreezing–changing–refreezing) model with Kelman’s

(1958) ‘mechanisms of attitude change’ to create some supporting subheads under the

three phase headings. In later publications, including one titled ‘The mechanisms of

UNFREEZE

Diagnosis ActionDevelop plan

Institutionalizing new

concepts

Learning new concepts

Lewin’s classic

‘foundation’ 1947/1951 UNFREEZE CHANGE REFREEZE

Unfreezing:

-Lack of

confirmation/disconfirmation

-Induction of guilt -anxiety

-Creation of psych safety

Changing:

-Scanning interpersonal

environment

-Identifying with a model

Refreezing:

-Integrate new into personality

-Integrate new into

relationships

Develop

need for

change

Work toward change

Establish

change

relation-

ships

Stabilize

change

Achieve

terminal

relations

Unfreezing: Creating the

motivation to change

Assess need for

change: Scout for

change

agent/consultant

TerminateEvaluate

ACT1. Recognize

need for

revitalization

ACT3. Institutionalizing

change

ACT2.

Create

new

vision

ACT2.

Mobilize

commitment

ACT2.

Transition

Est.

sense of

urgency

Create

vision

Form

guiding

coalition

Institutional-

ize the new

ConsolidateCommun

-icate

vision

Plan

short

term

wins

Empower

others

Lippitt et al.’s 1958

Schein and Bennis’

‘Lewinian’ Model of

Attitude Change (Schein,

1961; Schein and Bennis,

1965)

Kolb and Frohman’s

Planned Change Model

1970

Schein’s ‘Lewinian’ Model

of Change/Learning 2010

Tichy and Devanna’s ‘3

Acts’ of Transformation

1986

JP Kotter’s 8-Steps of

Change 1995

MOVING FORWARD

LOOKING BACK

Figure 2. CATS as a grand foundation.

Not long after Lippitt’s work was published, other fragments emerged that would rein-

force what we now consider to be the basis of change management. The first record we

can find of refreezing being used in a management context was by Schein in a 1961 article

‘Management development as a process of influence’. Schein, who cites the 1947 Human

Relations article, also describes the three elements as ‘phases’. Although he does not cite

Lippitt in his first interpretations of CATS, by 1965 in a more considered work with

Warren Bennis, Lippitt et al.’s work is widely acknowledged, particularly with respect to

furthering our knowledge of what Schein and Bennis term ‘change agentry’ (1965: 206).

Now connected to Lippitt’s, Schein’s interpretation loads the emphasis further toward

CATS as an intervention tool, calling the steps ‘phases of influence’ (Schein, 1961: 62).

As significant as the transposition from freezing to refreezing in this regard, is Schein’s

switching out of Lewin’s ‘moving’ for ‘changing’. Together, these re-interpretations

move CATS from a way change may be observed to a lever for a change agent. Schein

also back-fills the three phase (unfreezing–changing–refreezing) model with Kelman’s

(1958) ‘mechanisms of attitude change’ to create some supporting subheads under the

three phase headings. In later publications, including one titled ‘The mechanisms of

UNFREEZE

Diagnosis ActionDevelop plan

Institutionalizing new

concepts

Learning new concepts

Lewin’s classic

‘foundation’ 1947/1951 UNFREEZE CHANGE REFREEZE

Unfreezing:

-Lack of

confirmation/disconfirmation

-Induction of guilt -anxiety

-Creation of psych safety

Changing:

-Scanning interpersonal

environment

-Identifying with a model

Refreezing:

-Integrate new into personality

-Integrate new into

relationships

Develop

need for

change

Work toward change

Establish

change

relation-

ships

Stabilize

change

Achieve

terminal

relations

Unfreezing: Creating the

motivation to change

Assess need for

change: Scout for

change

agent/consultant

TerminateEvaluate

ACT1. Recognize

need for

revitalization

ACT3. Institutionalizing

change

ACT2.

Create

new

vision

ACT2.

Mobilize

commitment

ACT2.

Transition

Est.

sense of

urgency

Create

vision

Form

guiding

coalition

Institutional-

ize the new

ConsolidateCommun

-icate

vision

Plan

short

term

wins

Empower

others

Lippitt et al.’s 1958

Schein and Bennis’

‘Lewinian’ Model of

Attitude Change (Schein,

1961; Schein and Bennis,

1965)

Kolb and Frohman’s

Planned Change Model

1970

Schein’s ‘Lewinian’ Model

of Change/Learning 2010

Tichy and Devanna’s ‘3

Acts’ of Transformation

1986

JP Kotter’s 8-Steps of

Change 1995

MOVING FORWARD

LOOKING BACK

Figure 2. CATS as a grand foundation.

Secure Best Marks with AI Grader

Need help grading? Try our AI Grader for instant feedback on your assignments.

Cummings et al. 43

change’, Schein creates tables that list his development of Lewin’s idea with more clar-

ity. In so doing, CATS becomes a basis for a seven-stage ‘Model of attitude change’

(Schein and Bennis, 1965: 275 – see Figure 2); and a seven-stage approach to process

consulting (Schein, 1969).

While Schein originally acknowledged that what he had developed was a ‘deriva-

tion of the change model developed by Lewin’ (1961: 62), later works will attribute

more authority to Lewin. By 1965, CATS will be described as ‘what Lewin described

as the stages of change’ (Schein and Bennis, 1965: 275). By 1985, ‘Lewinian change

theory’ (Schein, 1985: 309). By 1992, what Lewin found to be ‘the fundamental[s]

underlying any change in a human system’ (Schein, 1992: 298). It is these formations,

rather than what Lewin actually wrote, that will enable the criticism of Lewin: that his

model is too instrumental, too simplistic and mechanistic for the complexities of the

modern world.

While Schein and Lippitt had good reason to invoke Lewin and develop his sketchy

idea, another less directed element would later fill in the background to the emerging

freezing/refreezing metaphorical model. The Tavistock Institute was greatly influenced

by Lewin, but, independent of him, Europe’s leading think-tank on the fledgling field of

management had launched a major research project on resistance to change that would

influence British management thinking for many subsequent years. This was The Glacier

Project, named for the company that had agreed to be the subject of the study, the Glacier

Steel Company. One might think that if Lewin’s CATS had been seen as a big deal at this

time, a link between a great man’s model that spoke of unfreezing/refreezing and a pro-

ject on resistance to change called Glacier would be made much of. But not yet. Long-

time Lewin fan and project leader Eliot Jacques’ (1951) book on the project does not

mention CATS.

In later years, these disparate elements – Lippitt and Schein’s interpretations and the

glacial freezing/unfreezing imagery – would accumulate into the historical narrative we

accept today. But up until the late 1970s the idea of CATS as a foundational theory

authored by the great Kurt Lewin had little influence on the mainstream of management

education. In fact, the first comprehensive histories of management either do not men-

tion Lewin at all (George, 1968); or mention him, but only in relation concepts other than

CATS (Wren, 1972). The first edition of Organizational Behavior: Concepts and

Controversies, by Stephen Robbins (1979) – typical of the new form of comprehensive

management textbooks that still guide teaching today – does not mention Lewin in the

main text. However, a chapter on organizational development (OD) states that: ‘In very

general terms, planned change can be described as consisting of three stages: unfreezing,

changing and refreezing’ (Robbins, 1979: 377). A footnote to this statement cites ‘Lewin,

1951’. But the lack of a page reference and Robbins’ arrangement of the terms suggests

some other influence. Much more would be made by looking back at CATS, moving

forward into the 1980s and beyond.

Archaeological form

Stepping back from the genealogy of the fragments that would be ordered into the history

of change management at a later stage, an archaeological view may help explain how

change’, Schein creates tables that list his development of Lewin’s idea with more clar-

ity. In so doing, CATS becomes a basis for a seven-stage ‘Model of attitude change’

(Schein and Bennis, 1965: 275 – see Figure 2); and a seven-stage approach to process

consulting (Schein, 1969).

While Schein originally acknowledged that what he had developed was a ‘deriva-

tion of the change model developed by Lewin’ (1961: 62), later works will attribute

more authority to Lewin. By 1965, CATS will be described as ‘what Lewin described

as the stages of change’ (Schein and Bennis, 1965: 275). By 1985, ‘Lewinian change

theory’ (Schein, 1985: 309). By 1992, what Lewin found to be ‘the fundamental[s]

underlying any change in a human system’ (Schein, 1992: 298). It is these formations,

rather than what Lewin actually wrote, that will enable the criticism of Lewin: that his

model is too instrumental, too simplistic and mechanistic for the complexities of the

modern world.

While Schein and Lippitt had good reason to invoke Lewin and develop his sketchy

idea, another less directed element would later fill in the background to the emerging

freezing/refreezing metaphorical model. The Tavistock Institute was greatly influenced

by Lewin, but, independent of him, Europe’s leading think-tank on the fledgling field of

management had launched a major research project on resistance to change that would

influence British management thinking for many subsequent years. This was The Glacier

Project, named for the company that had agreed to be the subject of the study, the Glacier

Steel Company. One might think that if Lewin’s CATS had been seen as a big deal at this

time, a link between a great man’s model that spoke of unfreezing/refreezing and a pro-

ject on resistance to change called Glacier would be made much of. But not yet. Long-

time Lewin fan and project leader Eliot Jacques’ (1951) book on the project does not

mention CATS.

In later years, these disparate elements – Lippitt and Schein’s interpretations and the

glacial freezing/unfreezing imagery – would accumulate into the historical narrative we

accept today. But up until the late 1970s the idea of CATS as a foundational theory

authored by the great Kurt Lewin had little influence on the mainstream of management

education. In fact, the first comprehensive histories of management either do not men-

tion Lewin at all (George, 1968); or mention him, but only in relation concepts other than

CATS (Wren, 1972). The first edition of Organizational Behavior: Concepts and

Controversies, by Stephen Robbins (1979) – typical of the new form of comprehensive

management textbooks that still guide teaching today – does not mention Lewin in the

main text. However, a chapter on organizational development (OD) states that: ‘In very

general terms, planned change can be described as consisting of three stages: unfreezing,

changing and refreezing’ (Robbins, 1979: 377). A footnote to this statement cites ‘Lewin,

1951’. But the lack of a page reference and Robbins’ arrangement of the terms suggests

some other influence. Much more would be made by looking back at CATS, moving

forward into the 1980s and beyond.

Archaeological form

Stepping back from the genealogy of the fragments that would be ordered into the history

of change management at a later stage, an archaeological view may help explain how

44 Human Relations 69(1)

these fragments begin to be enveloped toward the form of Lewin’s ‘classic model’ that

we accept today. The ‘conditions of possibility’ of that version of CATS fit with particu-

lar problems, viewpoints and values that framed the development of management knowl-

edge in the 1980s. Below, we examine five of these conditions that promoted the

development of ‘Lewin’s classic model’ as a key foundation of change management.

1. American industry and management consultancies seek to compete diffeAround

1980 a new phenomenon occurred: pop-management. Demand was fuelled by a growing

group made anxious by their own status mobility, the rise of Japan’s business culture and

the comparative decline of US industry. An enlarged managerial class, eager for the

knowledge that would help them climb the ladders of the new knowledge economy,