Unfreezing Change as Three Steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin's Legacy for Change Management - A Critical Analysis

Added on 2023-04-23

28 Pages18790 Words488 Views

human relations

2016, Vol. 69(1) 33–60

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726715577707

hum.sagepub.comhuman relations

Unfreezing change as three

steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s

legacy for change management

Stephen Cummings

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Todd Bridgman

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Kenneth G Brown

University of Iowa, USA

Abstract

Kurt Lewin’s ‘changing as three steps’ (unfreezing changing refreezing) is regarded

by many as the classic or fundamental approach to managing change. Lewin has been

criticized by scholars for over-simplifying the change process and has been defended by

others against such charges. However, what has remained unquestioned is the model’s

foundational significance. It is sometimes traced (if it is traced at all) to the first article

ever published in Human Relations. Based on a comparison of what Lewin wrote about

changing as three steps with how this is presented in later works, we argue that he

never developed such a model and it took form after his death. We investigate how and

why ‘changing as three steps’ came to be understood as the foundation of the fledgling

subfield of change management and to influence change theory and practice to this day,

and how questioning this supposed foundation can encourage innovation.

Keywords

CATS, changing as three steps, change management, Kurt Lewin, management history,

Michel Foucault

Corresponding author:

Stephen Cummings, Victoria Business School, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Email: stephen.cummings@vuw.ac.nz

577707HUM0010.1177/0018726715577707Human RelationsBridgman et al.

research-article2015

2016, Vol. 69(1) 33–60

© The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726715577707

hum.sagepub.comhuman relations

Unfreezing change as three

steps: Rethinking Kurt Lewin’s

legacy for change management

Stephen Cummings

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Todd Bridgman

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Kenneth G Brown

University of Iowa, USA

Abstract

Kurt Lewin’s ‘changing as three steps’ (unfreezing changing refreezing) is regarded

by many as the classic or fundamental approach to managing change. Lewin has been

criticized by scholars for over-simplifying the change process and has been defended by

others against such charges. However, what has remained unquestioned is the model’s

foundational significance. It is sometimes traced (if it is traced at all) to the first article

ever published in Human Relations. Based on a comparison of what Lewin wrote about

changing as three steps with how this is presented in later works, we argue that he

never developed such a model and it took form after his death. We investigate how and

why ‘changing as three steps’ came to be understood as the foundation of the fledgling

subfield of change management and to influence change theory and practice to this day,

and how questioning this supposed foundation can encourage innovation.

Keywords

CATS, changing as three steps, change management, Kurt Lewin, management history,

Michel Foucault

Corresponding author:

Stephen Cummings, Victoria Business School, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand.

Email: stephen.cummings@vuw.ac.nz

577707HUM0010.1177/0018726715577707Human RelationsBridgman et al.

research-article2015

34 Human Relations 69(1)

The fundamental assumptions underlying any change in a human system are derived originally

from Kurt Lewin (1947). (Schein, 2010: 299)

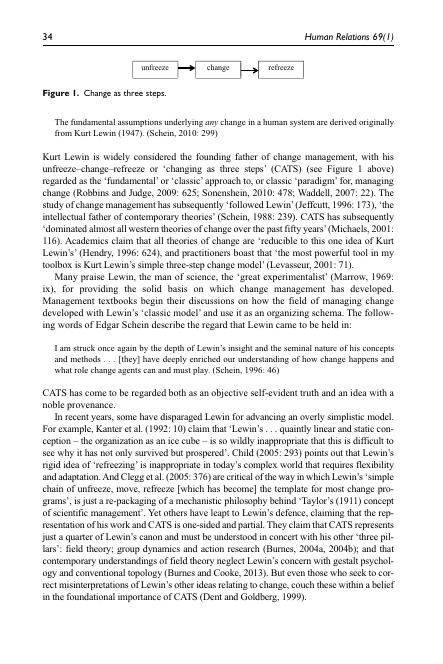

Kurt Lewin is widely considered the founding father of change management, with his

unfreeze–change–refreeze or ‘changing as three steps’ (CATS) (see Figure 1 above)

regarded as the ‘fundamental’ or ‘classic’ approach to, or classic ‘paradigm’ for, managing

change (Robbins and Judge, 2009: 625; Sonenshein, 2010: 478; Waddell, 2007: 22). The

study of change management has subsequently ‘followed Lewin’ (Jeffcutt, 1996: 173), ‘the

intellectual father of contemporary theories’ (Schein, 1988: 239). CATS has subsequently

‘dominated almost all western theories of change over the past fifty years’ (Michaels, 2001:

116). Academics claim that all theories of change are ‘reducible to this one idea of Kurt

Lewin’s’ (Hendry, 1996: 624), and practitioners boast that ‘the most powerful tool in my

toolbox is Kurt Lewin’s simple three-step change model’ (Levasseur, 2001: 71).

Many praise Lewin, the man of science, the ‘great experimentalist’ (Marrow, 1969:

ix), for providing the solid basis on which change management has developed.

Management textbooks begin their discussions on how the field of managing change

developed with Lewin’s ‘classic model’ and use it as an organizing schema. The follow-

ing words of Edgar Schein describe the regard that Lewin came to be held in:

I am struck once again by the depth of Lewin’s insight and the seminal nature of his concepts

and methods . . . [they] have deeply enriched our understanding of how change happens and

what role change agents can and must play. (Schein, 1996: 46)

CATS has come to be regarded both as an objective self-evident truth and an idea with a

noble provenance.

In recent years, some have disparaged Lewin for advancing an overly simplistic model.

For example, Kanter et al. (1992: 10) claim that ‘Lewin’s . . . quaintly linear and static con-

ception – the organization as an ice cube – is so wildly inappropriate that this is difficult to

see why it has not only survived but prospered’. Child (2005: 293) points out that Lewin’s

rigid idea of ‘refreezing’ is inappropriate in today’s complex world that requires flexibility

and adaptation. And Clegg et al. (2005: 376) are critical of the way in which Lewin’s ‘simple

chain of unfreeze, move, refreeze [which has become] the template for most change pro-

grams’, is just a re-packaging of a mechanistic philosophy behind ‘Taylor’s (1911) concept

of scientific management’. Yet others have leapt to Lewin’s defence, claiming that the rep-

resentation of his work and CATS is one-sided and partial. They claim that CATS represents

just a quarter of Lewin’s canon and must be understood in concert with his other ‘three pil-

lars’: field theory; group dynamics and action research (Burnes, 2004a, 2004b); and that

contemporary understandings of field theory neglect Lewin’s concern with gestalt psychol-

ogy and conventional topology (Burnes and Cooke, 2013). But even those who seek to cor-

rect misinterpretations of Lewin’s other ideas relating to change, couch these within a belief

in the foundational importance of CATS (Dent and Goldberg, 1999).

unfreeze change refreeze

Figure 1. Change as three steps.

The fundamental assumptions underlying any change in a human system are derived originally

from Kurt Lewin (1947). (Schein, 2010: 299)

Kurt Lewin is widely considered the founding father of change management, with his

unfreeze–change–refreeze or ‘changing as three steps’ (CATS) (see Figure 1 above)

regarded as the ‘fundamental’ or ‘classic’ approach to, or classic ‘paradigm’ for, managing

change (Robbins and Judge, 2009: 625; Sonenshein, 2010: 478; Waddell, 2007: 22). The

study of change management has subsequently ‘followed Lewin’ (Jeffcutt, 1996: 173), ‘the

intellectual father of contemporary theories’ (Schein, 1988: 239). CATS has subsequently

‘dominated almost all western theories of change over the past fifty years’ (Michaels, 2001:

116). Academics claim that all theories of change are ‘reducible to this one idea of Kurt

Lewin’s’ (Hendry, 1996: 624), and practitioners boast that ‘the most powerful tool in my

toolbox is Kurt Lewin’s simple three-step change model’ (Levasseur, 2001: 71).

Many praise Lewin, the man of science, the ‘great experimentalist’ (Marrow, 1969:

ix), for providing the solid basis on which change management has developed.

Management textbooks begin their discussions on how the field of managing change

developed with Lewin’s ‘classic model’ and use it as an organizing schema. The follow-

ing words of Edgar Schein describe the regard that Lewin came to be held in:

I am struck once again by the depth of Lewin’s insight and the seminal nature of his concepts

and methods . . . [they] have deeply enriched our understanding of how change happens and

what role change agents can and must play. (Schein, 1996: 46)

CATS has come to be regarded both as an objective self-evident truth and an idea with a

noble provenance.

In recent years, some have disparaged Lewin for advancing an overly simplistic model.

For example, Kanter et al. (1992: 10) claim that ‘Lewin’s . . . quaintly linear and static con-

ception – the organization as an ice cube – is so wildly inappropriate that this is difficult to

see why it has not only survived but prospered’. Child (2005: 293) points out that Lewin’s

rigid idea of ‘refreezing’ is inappropriate in today’s complex world that requires flexibility

and adaptation. And Clegg et al. (2005: 376) are critical of the way in which Lewin’s ‘simple

chain of unfreeze, move, refreeze [which has become] the template for most change pro-

grams’, is just a re-packaging of a mechanistic philosophy behind ‘Taylor’s (1911) concept

of scientific management’. Yet others have leapt to Lewin’s defence, claiming that the rep-

resentation of his work and CATS is one-sided and partial. They claim that CATS represents

just a quarter of Lewin’s canon and must be understood in concert with his other ‘three pil-

lars’: field theory; group dynamics and action research (Burnes, 2004a, 2004b); and that

contemporary understandings of field theory neglect Lewin’s concern with gestalt psychol-

ogy and conventional topology (Burnes and Cooke, 2013). But even those who seek to cor-

rect misinterpretations of Lewin’s other ideas relating to change, couch these within a belief

in the foundational importance of CATS (Dent and Goldberg, 1999).

unfreeze change refreeze

Figure 1. Change as three steps.

Cummings et al. 35

It seems that everybody in the management literature accepts CATS’ pre-eminence as

a foundation upon which the field of change management is built. We argue that CATS

was not as significant in Lewin’s writing as both his critics and supporters have either

assumed or would have us believe. This foundation of change management has less to do

with what Lewin actually wrote and more to do with others’ repackaging and marketing.

By adopting a Foucauldian approach, we first outline the dubious assumptions held

about Lewin and CATS, how this framework and the noble founder claimed to have

discovered it took form as a foundation of change management, and was then further

developed to fit the narrative of a field that has claimed to build on and advance beyond

it. In this light, it is little wonder that those who know only a little of Lewin are surprised

that he could have been so simplistic, and that those with a stake in seeing the field of

change management develop and grow would see more sophistication and complexity in

CATS that others had supposedly missed.

By going back and looking at what Lewin wrote (particularly the most commonly

cited reference for CATS, ‘Lewin, 1947’: the first article ever published in Human

Relations published just weeks after Lewin’s death), we see that what we know of CATS

today is largely a post hoc reconstruction. Our forensic examination of the past is not,

however, an end in itself. Rather, it encourages us to think differently about the future of

change management that we can collectively create. In that spirit, we conclude by offer-

ing two alternative future directions for teaching and researching change in organization

inspired by returning to ‘Lewin, 1947’ and reading it anew.

Dubious assumptions

Students of change management, and management generally, are informed that Lewin

was a great scientist with a keen interest in management, that discovering CATS was one

of his greatest endeavours, and that his episodic and simplistic approach to managing

change has subsequently been built upon and surpassed. However, the more that we

looked at the history of CATS, the more the anomalies between the accepted view today,

and what Lewin actually wrote, came into view.

Our first observation was that referencing of Lewin’s work in this regard is unusu-

ally lax. A footnote to an article by Schein (1996) on Lewin and CATS explains that:

I have deliberately avoided giving specific references to Lewin’s work because it is his basic

philosophy and concepts that have influenced me, and these run through all of his work as well

as the work of so many others who have founded the field of group dynamics and organization

development. (Schein, 1996: 27)

This explanation of the unusual practice of writing an article about a theorist who has been

a great influence without making any references to his work, despite referencing the work

of others who have been less influential, encouraged us to look further. Most who write

about CATS, if they cite anything, cite ‘Lewin, 1951’, Field Theory in Social Science. This

is not a book written by Lewin but an ‘edited compilation of his scattered papers’ (Shea,

1951: 65) published four years after his death in 1947. Field Theory was edited by Dorwin

Cartwright as a second companion volume to an earlier collection of Lewin’s works com-

piled by Kurt Lewin’s widow, with a foreword by Gordon Allport (Lewin, 1948).

It seems that everybody in the management literature accepts CATS’ pre-eminence as

a foundation upon which the field of change management is built. We argue that CATS

was not as significant in Lewin’s writing as both his critics and supporters have either

assumed or would have us believe. This foundation of change management has less to do

with what Lewin actually wrote and more to do with others’ repackaging and marketing.

By adopting a Foucauldian approach, we first outline the dubious assumptions held

about Lewin and CATS, how this framework and the noble founder claimed to have

discovered it took form as a foundation of change management, and was then further

developed to fit the narrative of a field that has claimed to build on and advance beyond

it. In this light, it is little wonder that those who know only a little of Lewin are surprised

that he could have been so simplistic, and that those with a stake in seeing the field of

change management develop and grow would see more sophistication and complexity in

CATS that others had supposedly missed.

By going back and looking at what Lewin wrote (particularly the most commonly

cited reference for CATS, ‘Lewin, 1947’: the first article ever published in Human

Relations published just weeks after Lewin’s death), we see that what we know of CATS

today is largely a post hoc reconstruction. Our forensic examination of the past is not,

however, an end in itself. Rather, it encourages us to think differently about the future of

change management that we can collectively create. In that spirit, we conclude by offer-

ing two alternative future directions for teaching and researching change in organization

inspired by returning to ‘Lewin, 1947’ and reading it anew.

Dubious assumptions

Students of change management, and management generally, are informed that Lewin

was a great scientist with a keen interest in management, that discovering CATS was one

of his greatest endeavours, and that his episodic and simplistic approach to managing

change has subsequently been built upon and surpassed. However, the more that we

looked at the history of CATS, the more the anomalies between the accepted view today,

and what Lewin actually wrote, came into view.

Our first observation was that referencing of Lewin’s work in this regard is unusu-

ally lax. A footnote to an article by Schein (1996) on Lewin and CATS explains that:

I have deliberately avoided giving specific references to Lewin’s work because it is his basic

philosophy and concepts that have influenced me, and these run through all of his work as well

as the work of so many others who have founded the field of group dynamics and organization

development. (Schein, 1996: 27)

This explanation of the unusual practice of writing an article about a theorist who has been

a great influence without making any references to his work, despite referencing the work

of others who have been less influential, encouraged us to look further. Most who write

about CATS, if they cite anything, cite ‘Lewin, 1951’, Field Theory in Social Science. This

is not a book written by Lewin but an ‘edited compilation of his scattered papers’ (Shea,

1951: 65) published four years after his death in 1947. Field Theory was edited by Dorwin

Cartwright as a second companion volume to an earlier collection of Lewin’s works com-

piled by Kurt Lewin’s widow, with a foreword by Gordon Allport (Lewin, 1948).

36 Human Relations 69(1)

Normally in academic writing, providing a name and date reference without a page

number implies that the idea, example or concept referred to is a key aspect of the book

or article. Of the nearly 10,000 citations to ‘Lewin, 1951’ listed on Google Scholar,

none of the first 100 (that is, the most highly cited of those who cite Lewin), provides

a page reference. But despite this, mention of CATS in Field Theory is devilishly dif-

ficult to find. It is the subject of just two short paragraphs (131 words) in a 338 page

book (1951: 228). 1

As one reviewer of the day makes clear, Lewin 1951 contains ‘nothing, other than the

editor’s introduction, that has not been published before’ (Lindzey, 1952: 132). And the

fragment that would be developed into the CATS model is from an article published in

1947 titled ‘Frontiers in Group Dynamics’: the first article of the first issue of Human

Relations (Lewin, 1947a). It is buried there in the 24th of 25 sub-sections in a 37 page

article. Unlike the other points made in Field Theory or the 1947 article, no empirical

evidence is provided or graphical illustration given of CATS, and unlike Lewin’s other

writings, the idea is not well-integrated with other elements. It is merely described as a

way that ‘planned social change may be thought of’ (Lewin, 1947a: 36; 1951: 231); an

example explaining (in an abstract way) the group dynamics of social change and the

advantages of group versus individual decision making. It appears almost as an after-

thought, or at least not fully thought out, given that the metaphor of ‘unfreezing’ and

‘freezing’ seems to contradict Lewin’s more detailed empirically-based theorizing of

‘quasi-equilibrium’, which is explained in considerable depth in Field Theory and argues

that groups are in a continual process of adaptation, rather than a steady or frozen state.

Apart from these few words published in 1947 (a few months after Lewin’s death), we

could find no other provenance for CATS in his work, unusual for a man lauded for his

thorough experimentation and desire to base social psychology on firm empirical

foundations.

A book edited by Newcomb and Hartley contains a chapter claimed to be ‘one of the

last articles to come from the pen of Kurt Lewin’ (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947: v). It

combines some ideas from the Human Relations article but gives a little more promi-

nence to CATS, labelling it a ‘Three-Step Procedure’ and attempting to link it to some

empirical evidence. However, this evidence seems completely disconnected from the

‘procedure’. The chapter begins (Lewin, 1947b: 330) by explaining that: ‘The following

experiments on group decision have been conducted during the last four years. They are

not in a state that permits definite conclusions’. None of the other chapters is framed in

such a tentative manner. And the editors acknowledge that the book went to press after

Lewin’s death (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947). All of which suggests that Lewin may not

have had the chance to fully revise the paper or that elements might have been finished

by the editors.

Despite the lack of emphasis on CATS in Lewin’s own writing, the impression is that

Lewin gave great thought to CATS. Lewin’s recent defenders see CATS as one of his

four main ‘interrelated elements’ (Burnes and Cooke, 2012: 1397) that Lewin ‘saw . . .

as an interrelated whole’ (Burnes, 2004a: 981); or one of ‘Lewin’s four elements’ (Edward

and Montessori, 2011: 8). But there seems no evidence for this. Having searched Lewin’s

publications written or translated into English (67 articles, book chapters and books), the

Normally in academic writing, providing a name and date reference without a page

number implies that the idea, example or concept referred to is a key aspect of the book

or article. Of the nearly 10,000 citations to ‘Lewin, 1951’ listed on Google Scholar,

none of the first 100 (that is, the most highly cited of those who cite Lewin), provides

a page reference. But despite this, mention of CATS in Field Theory is devilishly dif-

ficult to find. It is the subject of just two short paragraphs (131 words) in a 338 page

book (1951: 228). 1

As one reviewer of the day makes clear, Lewin 1951 contains ‘nothing, other than the

editor’s introduction, that has not been published before’ (Lindzey, 1952: 132). And the

fragment that would be developed into the CATS model is from an article published in

1947 titled ‘Frontiers in Group Dynamics’: the first article of the first issue of Human

Relations (Lewin, 1947a). It is buried there in the 24th of 25 sub-sections in a 37 page

article. Unlike the other points made in Field Theory or the 1947 article, no empirical

evidence is provided or graphical illustration given of CATS, and unlike Lewin’s other

writings, the idea is not well-integrated with other elements. It is merely described as a

way that ‘planned social change may be thought of’ (Lewin, 1947a: 36; 1951: 231); an

example explaining (in an abstract way) the group dynamics of social change and the

advantages of group versus individual decision making. It appears almost as an after-

thought, or at least not fully thought out, given that the metaphor of ‘unfreezing’ and

‘freezing’ seems to contradict Lewin’s more detailed empirically-based theorizing of

‘quasi-equilibrium’, which is explained in considerable depth in Field Theory and argues

that groups are in a continual process of adaptation, rather than a steady or frozen state.

Apart from these few words published in 1947 (a few months after Lewin’s death), we

could find no other provenance for CATS in his work, unusual for a man lauded for his

thorough experimentation and desire to base social psychology on firm empirical

foundations.

A book edited by Newcomb and Hartley contains a chapter claimed to be ‘one of the

last articles to come from the pen of Kurt Lewin’ (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947: v). It

combines some ideas from the Human Relations article but gives a little more promi-

nence to CATS, labelling it a ‘Three-Step Procedure’ and attempting to link it to some

empirical evidence. However, this evidence seems completely disconnected from the

‘procedure’. The chapter begins (Lewin, 1947b: 330) by explaining that: ‘The following

experiments on group decision have been conducted during the last four years. They are

not in a state that permits definite conclusions’. None of the other chapters is framed in

such a tentative manner. And the editors acknowledge that the book went to press after

Lewin’s death (Newcomb and Hartley, 1947). All of which suggests that Lewin may not

have had the chance to fully revise the paper or that elements might have been finished

by the editors.

Despite the lack of emphasis on CATS in Lewin’s own writing, the impression is that

Lewin gave great thought to CATS. Lewin’s recent defenders see CATS as one of his

four main ‘interrelated elements’ (Burnes and Cooke, 2012: 1397) that Lewin ‘saw . . .

as an interrelated whole’ (Burnes, 2004a: 981); or one of ‘Lewin’s four elements’ (Edward

and Montessori, 2011: 8). But there seems no evidence for this. Having searched Lewin’s

publications written or translated into English (67 articles, book chapters and books), the

Cummings et al. 37

Lewin archives at the University of Iowa, and the archives at the Tavistock Institute in

London where Human Relations was based, we can find no other origin for CATS.

Moreover, CATS was not regarded as significant when Lewin was alive or even in the

period after his death. Tributes after Lewin’s death acknowledge many important contri-

butions, such as action research, field theory and his concept of topology. But Alfred

Marrow (1947) does not mention CATS, nor does Dennis Likert, in the same issue of

Human Relations in which Lewin’s 1947 article appears. Ronald Lippitt’s (1947) obitu-

ary reviews 10 major contributions and CATS is not one of them. None of the many

reviews of ‘Lewin, 1951’ mentions it as a significant contribution (e.g. Kuhn, 1951;

Lasswell, 1952; Lindzey, 1952; Shea, 1951; Smith, 1951), and neither does Cartwright’s

extensive introduction to the volume. Papers on the contribution of Lewin to manage-

ment thought presented by his daughter Miriam Lewin Papanek (1973) and William B

Wolf (1973) at the Academy of Management conference do not refer to CATS. Twenty-

two years after Marrow wrote his obituary, his 300-page biography of Lewin does make

brief mention of CATS as a way that Lewin had ‘considered the change process’ shortly

before his death, but notes that Lewin had ‘recognized that problems of inducing change

would require significantly more research than had yet been carried out’ (1969: 223).

Even a three volume retrospective on the Tavistock Institute, which refers extensively to

Lewin’s work and the way he inspired other researchers, is silent on CATS (Trist and

Murray, 1990, 1993; Trist et al., 1997).

A few writers cite Lewin’s chapter in Newcomb and Hartley when referring to CATS.

A significant number cite the 1947 Human Relations article. But far more cite ‘Field

Theory, 1951’. And it is unlikely that many who cite Lewin now read his words: a lack

of connection that may explain some interesting fictions. The most significant may be

the invention of the word ‘refreezing’ as the full-stop at the end of what would become

change management’s foundational framework – a term that implies that frozen is an

organization’s natural state until an agent intervenes and zaps it (as later textbooks pro-

moting Lewin’s ‘classic model’ would say ‘refreezing the new change makes it perma-

nent’, Robbins, 1991: 646).

Lewin never wrote ‘refreezing’ anywhere. As far as we can ascertain, the re-phrasing

of Lewin’s freezing to ‘refreezing’ happened first in a 1950 conference paper by Lewin’s

former student Leon Festinger (Festinger and Coyle, 1950; reprinted in Festinger, 1980:

14). Festinger said that: ‘To Lewin, life was not static; it was changing, dynamic, fluid.

Lewin’s unfreezing-stabilizing-refreezing concept of change continues to be highly rel-

evant today’. It is worth noting that Festinger’s first sentence seems to contradict the

second, or at least to contradict later interpretations of Lewin as the developer of a model

that deals in static, or at least clearly delineated, steps. Furthermore, Festinger misrepre-

sents other elements; Lewin’s ‘moving’ is transposed into ‘stabilizing’, which shows

how open to interpretation Lewin’s nascent thinking was in this ‘preparadigmatic’ period

(Becher and Trowler, 2001: 33).

Other disconnected interpretations include Stephen Covey noting the influence of

‘Kirk Lewin’ on his thinking about change (Covey, 2004: 325); and citations for articles

titled ‘The ABCs of change management’ and ‘Frontiers in group mechanics’, both

claimed to have been written by Lewin and published in 1947. 2 On further investigation,

despite these articles being cited in respected academic books and articles (in Bidanda

Lewin archives at the University of Iowa, and the archives at the Tavistock Institute in

London where Human Relations was based, we can find no other origin for CATS.

Moreover, CATS was not regarded as significant when Lewin was alive or even in the

period after his death. Tributes after Lewin’s death acknowledge many important contri-

butions, such as action research, field theory and his concept of topology. But Alfred

Marrow (1947) does not mention CATS, nor does Dennis Likert, in the same issue of

Human Relations in which Lewin’s 1947 article appears. Ronald Lippitt’s (1947) obitu-

ary reviews 10 major contributions and CATS is not one of them. None of the many

reviews of ‘Lewin, 1951’ mentions it as a significant contribution (e.g. Kuhn, 1951;

Lasswell, 1952; Lindzey, 1952; Shea, 1951; Smith, 1951), and neither does Cartwright’s

extensive introduction to the volume. Papers on the contribution of Lewin to manage-

ment thought presented by his daughter Miriam Lewin Papanek (1973) and William B

Wolf (1973) at the Academy of Management conference do not refer to CATS. Twenty-

two years after Marrow wrote his obituary, his 300-page biography of Lewin does make

brief mention of CATS as a way that Lewin had ‘considered the change process’ shortly

before his death, but notes that Lewin had ‘recognized that problems of inducing change

would require significantly more research than had yet been carried out’ (1969: 223).

Even a three volume retrospective on the Tavistock Institute, which refers extensively to

Lewin’s work and the way he inspired other researchers, is silent on CATS (Trist and

Murray, 1990, 1993; Trist et al., 1997).

A few writers cite Lewin’s chapter in Newcomb and Hartley when referring to CATS.

A significant number cite the 1947 Human Relations article. But far more cite ‘Field

Theory, 1951’. And it is unlikely that many who cite Lewin now read his words: a lack

of connection that may explain some interesting fictions. The most significant may be

the invention of the word ‘refreezing’ as the full-stop at the end of what would become

change management’s foundational framework – a term that implies that frozen is an

organization’s natural state until an agent intervenes and zaps it (as later textbooks pro-

moting Lewin’s ‘classic model’ would say ‘refreezing the new change makes it perma-

nent’, Robbins, 1991: 646).

Lewin never wrote ‘refreezing’ anywhere. As far as we can ascertain, the re-phrasing

of Lewin’s freezing to ‘refreezing’ happened first in a 1950 conference paper by Lewin’s

former student Leon Festinger (Festinger and Coyle, 1950; reprinted in Festinger, 1980:

14). Festinger said that: ‘To Lewin, life was not static; it was changing, dynamic, fluid.

Lewin’s unfreezing-stabilizing-refreezing concept of change continues to be highly rel-

evant today’. It is worth noting that Festinger’s first sentence seems to contradict the

second, or at least to contradict later interpretations of Lewin as the developer of a model

that deals in static, or at least clearly delineated, steps. Furthermore, Festinger misrepre-

sents other elements; Lewin’s ‘moving’ is transposed into ‘stabilizing’, which shows

how open to interpretation Lewin’s nascent thinking was in this ‘preparadigmatic’ period

(Becher and Trowler, 2001: 33).

Other disconnected interpretations include Stephen Covey noting the influence of

‘Kirk Lewin’ on his thinking about change (Covey, 2004: 325); and citations for articles

titled ‘The ABCs of change management’ and ‘Frontiers in group mechanics’, both

claimed to have been written by Lewin and published in 1947. 2 On further investigation,

despite these articles being cited in respected academic books and articles (in Bidanda

38 Human Relations 69(1)

et al., 1999: 417; Kraft et al., 2008, 2009) and sounding like something the modern con-

ception of change management’s founding father might have written (anyone simple

enough to reduce all change to an ice cube might write about change being as easy or

mechanical as ABC), they do not actually exist.

As noted earlier, scholars like Clegg et al. (2005: 376) and Child (2005: 293) have

critiqued Lewin’s work for being too simple or mechanistic for modern environments or

unable to ‘represent the reality of change’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570). Indeed, in

recent years this has become something of a chorus, with a number of writers (e.g.

Palmer and Dunford, 2008; Stacey, 2007; Weick and Quinn, 1999) associating ‘classical

“episodic” views’ (Badham et al., 2012: 189) or ‘stage models, such as Lewin’s (1951)

classic’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570) with the ‘classical Lewinian unfreeze-movement-

refreeze formula, which had guided OD work from its inception’, but which was now

inappropriate ‘for the rapid pace of change at the beginning of the 21st century’ (Marshak

and Heracleous, 2004: 1051).

However, once again these prosecutions seem unrelated to what Lewin actually wrote.

Lewin never presented CATS in a linear diagrammatic form and he did not list it as bullet

points. Lewin was adamant that group dynamics must not be seen in simplistic or static

terms and believed that groups were never in a steady state, seeing them instead as being

in continuous movement, albeit having periods of relative stability or ‘quasi-stationary

equilibria’ (1951: 199). Lewin never wrote his idea was a model that could be used by a

change agent. He did, however, do significant research and re-published highly respected

articles that argued against Taylor’s mechanistic approach (Lewin, 1920; Marrow, 1969).

Perhaps the view of Lewin as a simplistic thinker emerges from his re-presentation

later in management textbooks, where the major output of his life-work appears to be a

rudimentary three-step model developed as a guide for managerial interventions. But it

is hard to imagine that anybody with Lewin’s background would hold such a simplisti-

cally ordered world-view. He studied philosophy and psychology. He worked at the

Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin until 1933 and devoted himself to

establishing a Psychological Institute at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem after leav-

ing the growing anti-Semitic chaos of Germany. His first major article contrasted

Aristotle and Galileo (Lewin, 1931), and ‘undoubtedly one of the last pieces of such

creative work from the pen of Kurt Lewin . . . mailed to the editor on January 3rd, 1947’

(Schilpp, 1949: xvi–xvii), was a piece on the philosophy of Ernst Cassirer (Lewin, 1949).

Lewin fled to the USA in 1933 to the School of Home Economics at Cornell University

where he studied the behaviour of children. From 1935 to 1945 he was at the Iowa Child

Welfare Research Station at the University of Iowa. While in Iowa, Lewin listed his title

as ‘Professor of Child Psychology’. But despite a highly dexterous mind and growing up

amid real chaos and change, he is demeaned by modern texts that smugly claim that his

CATS ‘has become obsolete [because] it applies to a world of certainty and predictability

[where it] was developed. [I]t reflects the environment of those times [which] has little

resemblance to today’s environment of constant and chaotic change’ (Robbins and Judge,

2009: 625–628).

To summarize, CATS is claimed to be one of Lewin’s most important pieces of

work, a cornerstone, which it was not. Lewin is claimed to have developed a three-step

et al., 1999: 417; Kraft et al., 2008, 2009) and sounding like something the modern con-

ception of change management’s founding father might have written (anyone simple

enough to reduce all change to an ice cube might write about change being as easy or

mechanical as ABC), they do not actually exist.

As noted earlier, scholars like Clegg et al. (2005: 376) and Child (2005: 293) have

critiqued Lewin’s work for being too simple or mechanistic for modern environments or

unable to ‘represent the reality of change’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570). Indeed, in

recent years this has become something of a chorus, with a number of writers (e.g.

Palmer and Dunford, 2008; Stacey, 2007; Weick and Quinn, 1999) associating ‘classical

“episodic” views’ (Badham et al., 2012: 189) or ‘stage models, such as Lewin’s (1951)

classic’ (Tsoukas and Chia, 2002: 570) with the ‘classical Lewinian unfreeze-movement-

refreeze formula, which had guided OD work from its inception’, but which was now

inappropriate ‘for the rapid pace of change at the beginning of the 21st century’ (Marshak

and Heracleous, 2004: 1051).

However, once again these prosecutions seem unrelated to what Lewin actually wrote.

Lewin never presented CATS in a linear diagrammatic form and he did not list it as bullet

points. Lewin was adamant that group dynamics must not be seen in simplistic or static

terms and believed that groups were never in a steady state, seeing them instead as being

in continuous movement, albeit having periods of relative stability or ‘quasi-stationary

equilibria’ (1951: 199). Lewin never wrote his idea was a model that could be used by a

change agent. He did, however, do significant research and re-published highly respected

articles that argued against Taylor’s mechanistic approach (Lewin, 1920; Marrow, 1969).

Perhaps the view of Lewin as a simplistic thinker emerges from his re-presentation

later in management textbooks, where the major output of his life-work appears to be a

rudimentary three-step model developed as a guide for managerial interventions. But it

is hard to imagine that anybody with Lewin’s background would hold such a simplisti-

cally ordered world-view. He studied philosophy and psychology. He worked at the

Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin until 1933 and devoted himself to

establishing a Psychological Institute at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem after leav-

ing the growing anti-Semitic chaos of Germany. His first major article contrasted

Aristotle and Galileo (Lewin, 1931), and ‘undoubtedly one of the last pieces of such

creative work from the pen of Kurt Lewin . . . mailed to the editor on January 3rd, 1947’

(Schilpp, 1949: xvi–xvii), was a piece on the philosophy of Ernst Cassirer (Lewin, 1949).

Lewin fled to the USA in 1933 to the School of Home Economics at Cornell University

where he studied the behaviour of children. From 1935 to 1945 he was at the Iowa Child

Welfare Research Station at the University of Iowa. While in Iowa, Lewin listed his title

as ‘Professor of Child Psychology’. But despite a highly dexterous mind and growing up

amid real chaos and change, he is demeaned by modern texts that smugly claim that his

CATS ‘has become obsolete [because] it applies to a world of certainty and predictability

[where it] was developed. [I]t reflects the environment of those times [which] has little

resemblance to today’s environment of constant and chaotic change’ (Robbins and Judge,

2009: 625–628).

To summarize, CATS is claimed to be one of Lewin’s most important pieces of

work, a cornerstone, which it was not. Lewin is claimed to have developed a three-step

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Related Documents

Improving Change Management: A Review of Two Articleslg...

|6

|1987

|449

Organizational Prevention of Resistance to Changelg...

|4

|596

|214

Leadership And Employee Involvementlg...

|10

|2749

|34

Management Organization Change Analysis 2022lg...

|5

|530

|2

Essay about Current Leadershiplg...

|9

|2736

|65

Challenges in Organizational Change Management: A Literature Reviewlg...

|12

|2752

|233